The Federal Receiver for Inmate Medical Services maintains direct control over inmate medical care provided in California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation facilities. In this post, we make recommendations on four specific Receiver proposals in the Governor's 2017-18 budget, related to: (1) medication management, (2) suicide watch, (3) health care appeals, and (4) managing health care equipment.

LAO Contact

March 3, 2017

The 2017-18 Budget

Federal Receiver for Inmate Medical Services

Overview of Inmate Medical Services Budget

Federal Receiver Maintains Direct Control Over Inmate Medical Care. In 2006, after finding the state failed to provide a constitutional level of medical care to prison inmates, the federal court in the Plata v. Brown case appointed a Receiver to take control over the direct management of the state’s prison medical care delivery system from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). This means that the Receiver, rather than the state, generally has control over medical care in state prisons. In order for the state to regain control, the state must demonstrate that it can provide a sustainable constitutional level of care. In March 2015, the Plata court issued an order outlining the process for transitioning responsibility back to the state. Under the order, responsibility for each institution, as well as overall statewide management of inmate medical care, must be delegated back to the state. As of January 2017, the Receiver has delegated care at ten institutions to CDCR.

Spending Proposed to Increase by $41 Million in 2017-18. The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $2.1 billion for inmate medical care in 2017-18, which is an increase of $41 million (2 percent) from the 2016-17 level. This increase is primarily due to increased pharmaceutical drug costs and additional staff needed to support various medical care operations, such as the distribution of pharmaceutical drugs to inmates.

Increased Staffing for Medication Management and Suicide Watch

LAO Bottom Line. We recommend that the Legislature direct the Receiver to report at budget hearings on the amount of overtime and registry staff savings that the Governor’s proposals to provide additional staffing resources for medication management and suicide watch would create. The Legislature could then use this information to adjust the proposals accordingly.

Background

Medication Management. Most medications are distributed to inmates from pill windows at various locations throughout each prison. Inmates typically line-up at these windows to receive their medication four times a day—morning, noon, later afternoon, and before they go to sleep. In addition, some medication is distributed to inmates to keep and use as needed, such as an asthma inhaler. Typically, Licensed Vocational Nurses (LVNs) distribute medication to inmates. The 2016-17 budget included at total of $80 million for LVNs engaged in medication management.

According to the Receiver, budgeted staffing levels have not been adequate to complete daily medication distribution. This is because the current staffing model used to determine level of LVNs and associated funding needed each year for medication management does not account for certain factors that have increased workload in recent years. Such factors include additional pill windows that have since been added to facilities and the need to distribute medication that inmates keep and use as needed. As a result, institutions have relied on overtime and registry staff to complete this increased workload not accounted for under the current staffing model. (Registry staff are contractors that provide services on an hourly basis when civil servants are unavailable.)

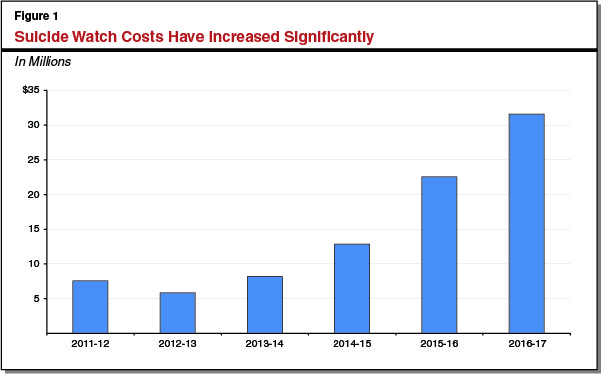

Suicide Watch. Mental Health Crisis Beds (MHCBs) are short-term beds for inmates who require 24-hour mental health care because they are a danger to themselves or others. Inmates who are a danger to themselves and are awaiting placement in MHCBs are typically placed on suicide watch. When an inmate is placed on suicide watch, staff members have to take shifts watching the inmate 24-hours per day. The Receiver reports that there are no positions currently dedicated to suicide watch and the workload has typically been addressed using overtime, registry staff, or redirecting existing staff. According to the Receiver, a variety of positions are used for this function, including correctional officers, registered nurses, physicians, and certified nursing assistants (CNAs), based on which position is available and the lowest cost. Correctional officers, registered nurses, and physicians are the most expensive positions used to perform suicide watch and CNAs are the least expensive. As a result of an increased number of suicide watches being completed, costs associated with suicide watch have increased significantly in recent years. As indicated in Figure 1, from 2011-12 to 2013-14, less than $10 million was spent on suicide watch per year. The Receiver is projecting that over $31 million will be spent on suicide watch in 2016-17—reflecting an average annual increase of 38 percent since 2013-14.

As suicide watch workload increased, the Receiver indicates that a greater proportion of suicide watch workload had to be completed using higher-cost staff, including correctional officers, registered nurses, and physicians. In 2015-16, CDCR spent $22.5 million on suicide watch. Of that amount, $6.3 million was for higher-cost staff and $16.2 million was for lower-cost positions, mostly CNAs.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget for 2017-18 includes two proposals to provide additional staffing resources to the Receiver’s office for medication management and suicide watch, in order to reduce the reliance on overtime and registry staff usage.

Medication Management ($8.9 Million). The Governor’s budget proposes $8.9 million from the General Fund and 105.2 additional positions for medication management based on a new staffing model developed by the Receiver that includes a sufficient number of LVN positions to staff each pill window throughout the day and distribute medication inmates are allowed to keep and use as needed.

Suicide Watch ($3.1 Million). The Governor’s budget proposes $3.1 million from the General Fund for 184.5 additional CNA positions, as well as temporary help to conduct suicide watch for patients awaiting transfer to MHCBs. We note that the total cost of the Governor’s proposal is $12.1 million. However, $9 million of the total cost would be offset by funding that is currently used for overtime and registry staff costs associated with suicide watch.

Proposals Do Not Reflect Full Impacts From Reduced Overtime and Registry Staff

As discussed above, additional medication management workload not captured by the Receiver’s current staffing model was generally completed with overtime and registry staff. Because the new staffing model should account for all medication management workload, costs associated with the use of overtime and registry staff for medication management should be largely eliminated. We note, however, that the proposal does not reflect a reduction in overtime or registry related to medication management. At the time of this analysis, the Receiver was not able to provide a sufficient amount of information to estimate the level of savings possible.

As discussed above, $9 million in savings from reducing the use of overtime and registry for suicide watch is accounted for in the proposal to add 184.5 CNAs. However, it appears that this adjustment does not account for the full reduction in overtime and registry costs. We estimate that the 184.5 new CNA positions would work 316,000 hours at a total cost of $10.5 million. However, based on information provided by the Receiver, we estimate that this could avoid the need for $13.3 million in overtime and registry costs—about $4.3 million more than assumed in the Governor’s budget. However, it is possible that some of the suicide watch workload is currently being covered by individuals who are being redirected from other duties, such as guarding rehabilitation programs or providing medical treatment to inmates. This could reduce the additional $4.3 million in savings identified above as these redirected positions would return to their original duties rather than be eliminated. At the time of this analysis, the Receiver has not provided sufficient information to assess the extent to which this is the case.

LAO Recommendation

Direct Receiver to Report on Estimated Savings and Modify Proposal Accordingly. Given that the proposals could create savings from reducing overtime and registry staff costs for medication management and suicide watch, we find that they merit legislative consideration. However, because the proposals do not appear to account for all of the savings from reduced overtime and registry staff costs, we recommend the Legislature direct the Receiver to report at budget hearings this spring on the full amount of savings created by each of the proposals. We recommend that the Legislature use this information to adjust the Receiver’s request accordingly.

Health Care Appeals Process

LAO Bottom Line. Given that the proposed health care appeals process would likely reduce costs, we recommend that the Legislature direct the Receiver to implement it at all institutions. However, because it could be managed within existing resources and would likely reduce costs, we find no reason to provide the Receiver with additional funding to implement it. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature reject the proposed funding.

Background

Health Care Appeals Process. Inmates who do not agree with health care decisions made by CDCR health care providers can appeal those decisions to the department. For example, an inmate who requests particular pain management treatment that a clinician does not agree is medically necessary could appeal that decision. After the appeal is filed, CDCR administrative staff at the prison receive the appeal and prepare the appeal for review, such as by collecting relevant documents related to the appeal. (Each prison has two staff members dedicated to these activities.) Once an appeal is initiated, it goes through as many as three levels of review:

Administrative Review. During this initial administrative review, the administrative staff that prepare the appeal make decisions on how the appeal will proceed. For example, staff could choose to deny the appeal for various reasons—including if the appeal is missing documents, contains threats or abusive language, or is a duplicate of another appeal. If an urgent health care issue is identified in reviewing the appeal, the administrative staff could refer the inmate to the appropriate health care discipline to address the urgent issue. For example, they may refer the inmate to a new primary care physician (PCP) who would provide care to address any urgent needs. In some cases, the inmate could decide to withdraw the appeal (such as in cases where staff were able to address the inmate’s concerns). Appeals that are not denied, referred to a health care discipline, or withdrawn, move to the next stage of the process.

Clinical Review. This stage of the process is essentially the same as the above administrative review except that it is done by a clinical staff member (typically a registered nurse) rather than a nonclinical staff member. Appeals that are not denied, referred to a health care discipline, or withdrawn, move to the third stage of the process.

Headquarters Review. Appeals that continue to remain unresolved after the clinical review are forwarded to California Correctional Health Care Services (CCHCS) headquarters, currently overseen by the federal Receiver, where it is reviewed by the Inmate Correspondence and Appeals Branch. Decisions made by the branch cannot be appealed.

The Receiver has identified various concerns with the existing appeals process. For example, the Receiver indicates that the administrative and clinical reviews at the institution are often redundant because both the administrative staff and the clinical staff reviewing the appeal look for urgent health care concerns. According to the Receiver, such duplication delays the resolution of some appeals.

Streamlined Health Care Appeals Pilot. In order to address the above concerns, the Receiver used existing resources in 2015 to pilot a more simplified health care appeals process at three institutions that combined the first two stages of the current process. These three institutions were the Central California Women’s Facility in Chowchilla, the Substance Abuse Treatment Facility in Corcoran, and the California State Prison Solano in Vacaville. Under the pilot, after the appeal was prepared by administrative staff, it was only reviewed by a registered nurse at the institution who specializes in appeals—rather than by an administrative staff member.

In addition to reducing the length of the appeals process, the Receiver identified a couple other benefits from the pilot. First, these nurses who specialize in appeals were able to address clinical issues earlier in the process, which resulted in more appeals being resolved at the institutional level. The Receiver indicates that this reduced the number of appeals that required a headquarters review. In addition, as a result of getting a nurse to meet with the inmate earlier in the process, fewer inmates requested PCP appointments as part of their appeal, which freed up PCPs for other responsibilities.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget proposes $5.4 million from the General Fund and 36 registered nurses specializing in appeals positions to implement the streamlined health care appeal process at all institutions. Under the proposal, 2 institutions with significantly above-average appeals would each receive 2 nurses, 24 institutions with near-average appeals would each receive 1 nurse, and 9 institutions with significantly lower-than-average appeals would have all of their appeals managed by 2 nurses at CCHCS headquarters. (The remaining six positions in the request are needed to provide coverage for these nurses if they are out on leave, such as when a nurse uses vacation or sick leave.)

LAO Assessment

Streamlined Appeals Process Makes Sense. Given that the streamlined health care appeals process is expected to resolve health care appeals more cost-effectively by providing clinical reviews earlier in the appeals process, expanding the pilot to all institutions makes sense.

Health Care Appeals Should Be Managed Within Existing Resources. The primary change in the proposed appeals process is that administrative staff would no longer review appeals. Instead, they would only prepare appeals and send them to a registered nurse for the clinical review. The nurse would conduct largely the same clinical review as they currently do under the existing process. If appeals are sent to headquarters for review, the headquarters staff would also follow the same review process currently in place. The Receiver has not provided an explanation of how reducing workload associated with the administrative review would result in a need for an increase in the number of nurses needed to complete clinical reviews. Given that the clinical review process would remain largely the same under the proposed appeal process, their workload would not significantly change. Moreover, during the pilot, the Receiver was able to use existing resources to perform clinical reviews of health care appeals.

New Appeals Process Could Actually Reduce Costs. The new appeals process may result in reduced workload and create savings. Workload would likely be reduced in several ways. First, by eliminating the administrative level of review, the administrative staff would only prepare appeals for the nurses to review. Second, the new process is anticipated to reduce the number of appeals that require headquarters review as part of the final appeals stage. Third, the new process is expected to more effectively address the clinical concerns of inmates who submit appeals, resulting in fewer inmates receiving PCP visits as part of the appeal process. Despite the potential for savings, the Receiver does not propose to score any savings.

LAO Recommendation

Direct Receiver to Implement New Process Without Additional Funding. Given that the new process would likely reduce costs, we recommend that the Legislature direct the Receiver to implement it at all institutions. However, because it could be managed within existing resources and would likely reduce costs, we find no reason to provide the Receiver with additional funding to implement it. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature reject the proposed funding.

Health Care Equipment Management Program

LAO Bottom Line. We recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal to implement a separate equipment management program for CDCR’s health care equipment, as the proposal does not address the existing challenges with the department’s management of non-health care equipment. Given the importance of ensuring that both health care and non-health care equipment is available for use when needed for inmates and staff, we also recommend that the Legislature direct the department to submit a comprehensive proposal to effectively manage all of its equipment.

Background

Equipment Management at CDCR. Equipment management involves systematically tracking equipment throughout its lifecycle to ensure that it is properly maintained and available for use when needed. CDCR’s Division of Adult Institutions (DAI) is currently responsible for managing all of the department’s equipment—such as computers, e-readers, and exam tables—including those used by health care programs. DAI equipment management staff use several separate electronic systems to track the department’s equipment. According to the department, the increasing volume and complexity of health care-related equipment, along with growth in equipment used by CDCR’s educational and vocational programs, have resulted in an unmanageable workload for DAI staff. Furthermore, the Receiver reports that inspectors have observed at several institutions that medical equipment is often improperly stored, damaged, or unaccounted for.

The Receiver indicates that if CDCR cannot sufficiently track and maintain its medical, mental health, and dental equipment, it risks spending unnecessarily to replace missing equipment, and the quality of health care could be compromised. As a result, in 2014 the Receiver hired two staff with existing resources to establish an equipment management unit within CCHCS. The Receiver reports that this initial effort highlighted the magnitude of the deficiencies in the equipment management process for inmate health care and concluded that existing DAI staffing levels were insufficient to provide the needed support.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget proposes a General Fund augmentation of $2 million and 25.3 additional positions in 2017-18 for the Receiver to develop, implement, and maintain a new system-wide equipment management program for CDCR’s health care equipment. Under the Governor’s proposal, the augmentation would increase to $3 million and 37 positions annually beginning in 2018-19. The requested resources would support four additional headquarters positions and one additional position at each of the state’s 33 prisons, all of which would report to CCHCS.

The proposed health care equipment management system would be separate from DAI’s existing equipment management system and would relieve DAI from the responsibility of managing health care equipment. The proposed staff would record and track all health care equipment in the Business Information System (BIS), the financial system of record for both CCHCS, and CDCR. We note that the equipment tracking functionalities of BIS are not currently widely used by DAI’s equipment management staff.

LAO Assessment

Both the Receiver and DAI report that the current staffing level and systems for managing all of the department’s equipment (including those related to health care) are inadequate. The Governor’s proposal attempts to address the existing challenge related to health care equipment in isolation from the larger problem that has been identified. Specifically, the proposal would establish a separate system and process for tracking health care equipment by creating a new unit at headquarters, developing new policies and procedures, using an electronic system that the department has not previously used for equipment management, and hiring new staff at each institution. We find that this bifurcated approach is problematic for three reasons:

- First, the proposal does not address DAI’s existing challenge in managing non-health care equipment.

- Second, creating a separate system for health care equipment would be inefficient. For example, under the proposal, each prison would have one position specifically dedicated to the management of health care equipment and one position specifically dedicated to management of all other equipment, with each position reporting to a different office within CDCR headquarters. Such an approach does not take into account the different needs across institutions and how those needs could change over time. This is because it is possible that some institutions may have a greater need for the management of non-health care equipment compared to the management of health care equipment.

- Finally, such a bifurcated approach would likely not make sense as various aspects of inmate medical care continue to be delegated back to CDCR. For example, the Receiver has delegated responsibility for inmate medical care at ten institutions back to CDCR to date. Given that CDCR will eventually be responsible for integrating all aspects of inmate medical care into its operations, it is problematic that the Receiver would initiate a bifurcated approach to asset management in the midst of this transition.

LAO Recommendation

In view of the above concerns, we recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal to implement a separate equipment management program for CDCR’s health care equipment. Given the importance of ensuring that both health care and non-health care equipment is available for use when needed for inmates and staff and that challenges with the existing management of equipment have been identified, we recommend that the Legislature direct the department to submit a comprehensive proposal to effectively improve the management of all equipment. The proposal should address DAI’s existing challenge in managing both health care and non-health care equipment, reflect the different equipment management needs across institutions, and account for any potential savings in equipment purchases.