LAO Contacts

January 8, 2018

The Potential Effects of Ending the

SSI Cash-Out

- Introduction

- Background

- What Happens to Household Eligibility and CalFresh Benefits if the State Ends the SSI Cash‑Out?

- Statewide Net Effect of Ending the SSI Cash‑Out on CalFresh Benefits In California

- Examples Of Potential Impacts of Ending SSI Cash‑Out on Poverty

- Legislative Options for Holding Households Harmless

- Additional Issues for Legislative Consideration

- Conclusion

- Appendix: CalFresh Eligibility and Benefit Calculation

Executive Summary

Supplemental Report Language (SRL) Required LAO to Report on Effects of Ending the “SSI Cash‑Out.” During deliberations on the 2017‑18 budget package, the Legislature directed our office to report on the programmatic and fiscal implications of ending a long‑standing state policy that provides Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Payment (SSI/SSP) recipients an extra $10 payment in lieu of their being eligible to receive federal food benefits through California’s CalFresh program. This is known as the SSI cash‑out or the CalFresh cash‑out. Due to data limitations, we were not able to develop our own estimates of the impact of ending the SSI cash‑out in California. Instead, we rely on estimates developed by Mathematica and modified by the Department of Social Services (DSS) to assess the potential impact of ending the SSI cash‑out on households, the state, and counties.

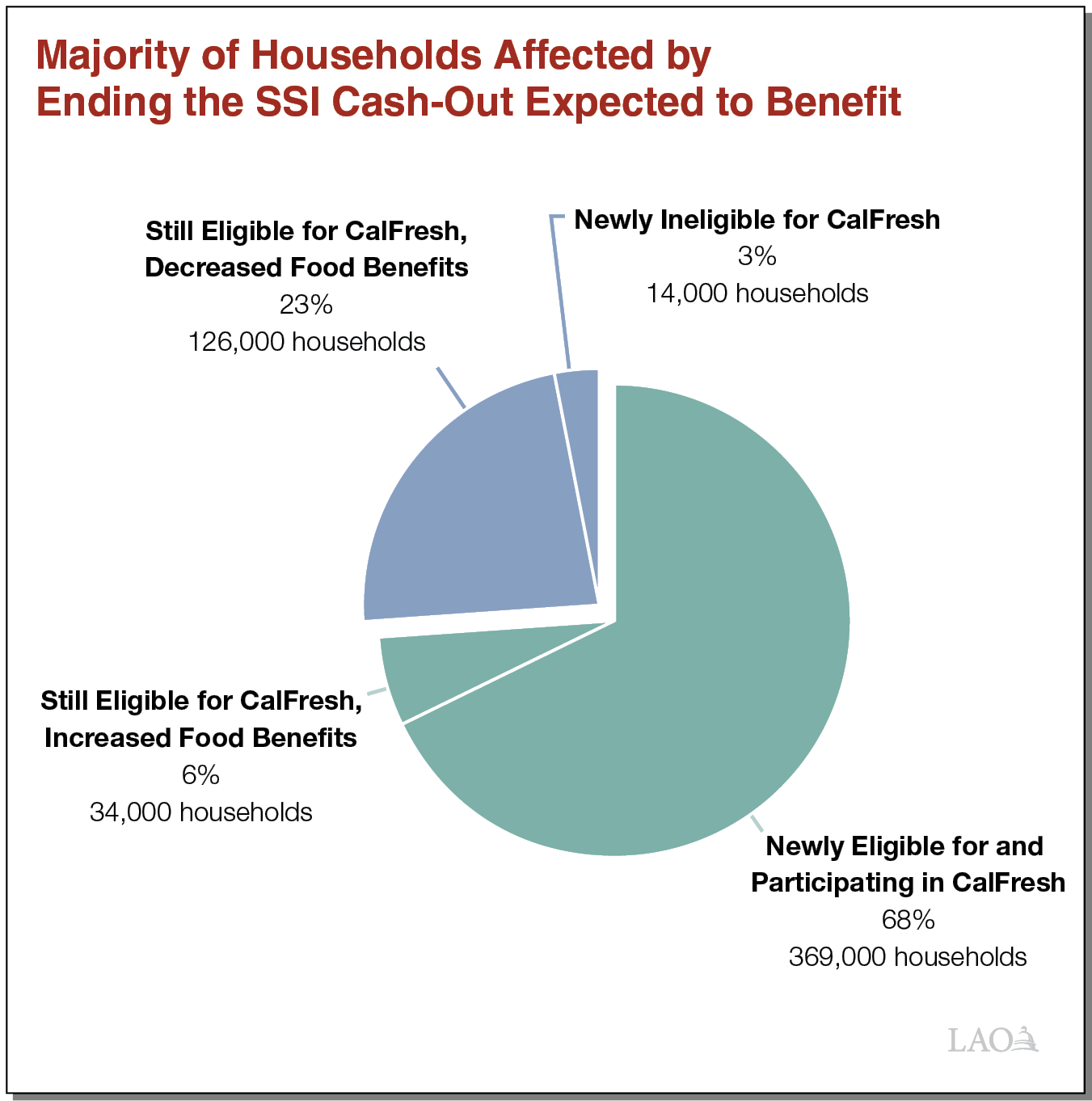

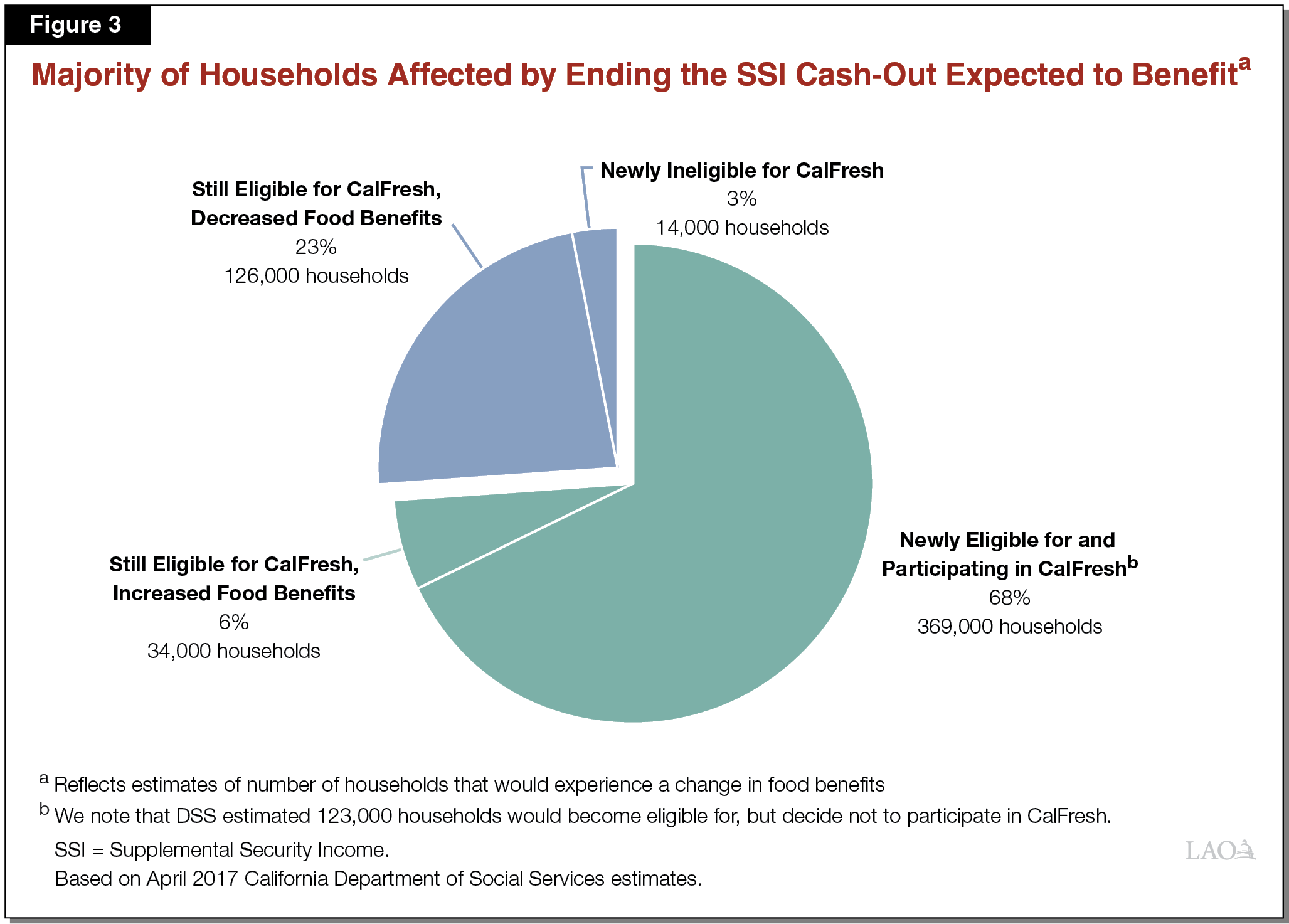

Ending the SSI Cash‑Out Expected to Increase Food Benefits for Most Households. As estimated by DSS in 2017, and shown in the figure below, most households affected by ending the SSI cash‑out would experience an increase in CalFresh benefits. These households are typically comprised solely of SSI/SSP members who would become newly eligible for and receive more CalFresh benefits today than the initial $10 payment provided to them in lieu of federal food benefits. The impacts are very different for current CalFresh households comprised of both SSI/SSP members and non‑SSI/SSP members. The vast majority of these households would experience a reduction in food benefits.

Key Factors to Consider in Deciding Whether to End the SSI Cash‑Out. Ending the SSI cash‑out in California would affect food benefits on a statewide and per household basis. Although difficult to predict, both of these effects are key factors for the Legislature to consider when weighing the trade‑offs of ending the SSI cash‑out:

- What Is the Statewide Net Effect on Total Food Benefits Received by California? Because some households will experience an increase in CalFresh benefits and others will experience a decrease in CalFresh benefits, the state could potentially draw down more or less total federal food benefits as a result of ending the SSI cash‑out. The statewide net effect on food benefits depends on a number of key assumptions (such as the number of eligible households that would opt to participate in CalFresh). Initial estimates from Mathematica and DSS show that the state would receive more food benefits, on net, by ending the SSI cash‑out. However, Mathematica’s and DSS’ estimates of the net increase in food benefits are very different—$3.5 million and $205 million, respectively. These different estimates illustrate how any variation in the underlying assumptions can create significantly different estimates of the net effect.

- How Do Households That Benefit From Ending the SSI Cash‑Out Compare to Households That Lose Food Benefits? In addition to considering the statewide net effect of ending the SSI cash‑out, the Legislature should consider which households would experience an increase in food benefits and which households would experience a decrease in food benefits, and how these households compare to one another in terms of income and resources. Mathematica and DSS estimates show that households that are expected to benefit from ending the SSI cash‑out have relatively less income than those who are expected to experience a reduction in food benefits. However, we note that even households that are expected to lose food benefits as a result of ending the SSI cash‑out, although relatively higher income than those who are expected to experience increased food benefits, are not necessarily far above the federal poverty level.

There Are Many Ways the Legislature Could Hold Households Negatively Affected by Ending the SSI Cash‑Out Harmless. The SRL required our office to provide potential hold harmless options for households that would experience a reduction in food benefits as a result of ending the SSI cash‑out. A hold harmless policy would create a state‑funded food program that would aim to backfill all, or a portion of, these lost CalFresh benefits. We provide a number of hold harmless options, ranging from a short‑term food benefit for the existing population to a long‑term food benefit for existing and future populations. We note that the costs and administrative complexity of these policies vary based on a number of policy and program decisions, such as whether the state food benefit will be provided to all or a subset of negatively affected households and if the benefit will be provided on a temporary or permanent basis.

Additional Issues That Merit Legislative Consideration. Finally, prior to making the decision to end the SSI cash‑out and implement a hold harmless policy, we identify several key issues that merit further consideration by the Legislature. These issues include (1) understanding the trade‑offs associated with keeping or ending the SSI cash‑out, (2) determining whether there is a way to get more updated estimates of the impact of ending the SSI cash‑out, (3) identifying ways to reduce potential administrative challenges and costs for the state and counties associated with ending the SSI cash‑out or instituting a hold harmless policy, and (4) whether instituting a hold harmless policy and providing a state food benefit would affect an individual’s eligibility for other public assistance programs.

Introduction

2017‑18 Supplemental Report Language (SRL) Requires Report on Implications of Ending the SSI Cash‑Out. During deliberations on the 2017‑18 budget package, the Legislature directed our office to report on the programmatic and fiscal implications of ending a long‑standing state policy that provides Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Payment (SSI/SSP) recipients an extra $10 payment in lieu of their being eligible to receive federal food benefits in California. This is known as the SSI cash‑out (or the CalFresh cash‑out). In this report, we describe the potential programmatic and fiscal effects of ending the SSI cash‑out in California. Next, we provide examples of how ending the SSI cash‑out would affect the poverty status of certain households. Finally, as directed by the SRL, we conclude by discussing potential options the Legislature could consider to hold households negatively affected by the elimination of the SSI cash‑out harmless and present additional issues that merit legislative consideration.

Significant Data Limitations. A significant challenge in assessing the potential impact of ending the SSI cash‑out is the notable limitation of available data. As a result, we were not able to develop our own estimates of the impact of ending the SSI cash‑out on the total amount of federal food benefits drawn down by the state or assess the effect of ending the SSI cash‑out on the poverty status of all affected households. Instead, we rely on estimates developed by Mathematica, a policy research organization, and modified by the Department of Social Services (DSS) to assess the potential impact of ending the SSI cash‑out on federal food benefits received by the state and note how these estimates could vary. Additionally, we provide examples of specific households to show how a change in federal food benefits as a result of ending the SSI cash‑out could ultimately impact their poverty level.

Background

CalFresh

The CalFresh program is California’s version of the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, which provides monthly food assistance to qualifying low‑income households. It is overseen at the state level by DSS and administered locally by county human services departments. During federal fiscal year (FFY) 2016‑17, an average of 4.3 million individuals (roughly 11 percent of the state’s population) received CalFresh benefits each month. The cost of food benefits in the CalFresh program, which totaled about $7 billion in FFY 2016‑17, is paid almost entirely by the federal government. Costs to administer the CalFresh program are shared among the federal government, the state, and counties. Total budgeted administrative costs in 2016‑17 were $1.9 billion ($956 million federal funds, $683 million General Fund, and $279 million county funds).

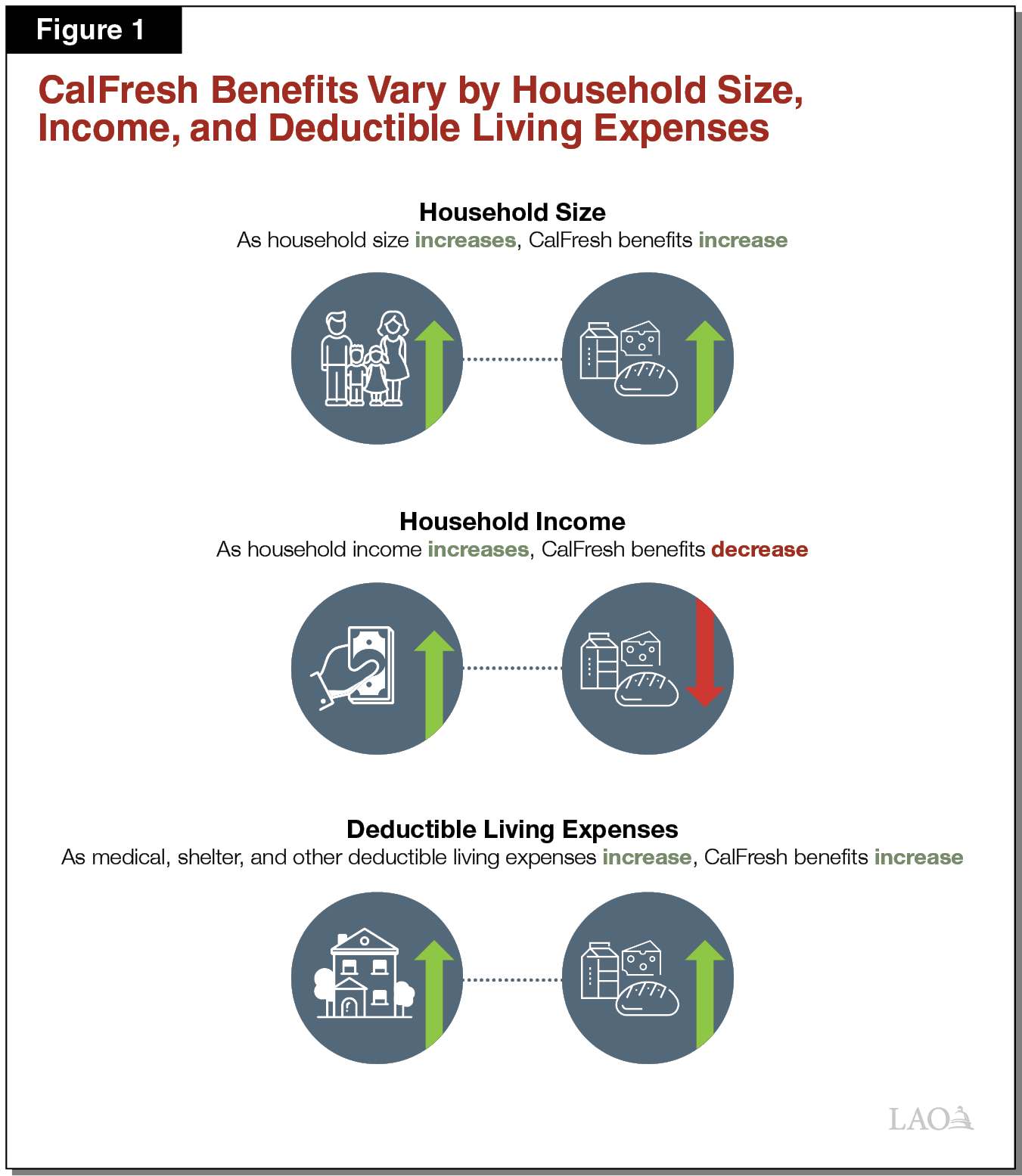

CalFresh Eligibility and Benefit Determination. CalFresh eligibility and benefits are determined on a household basis. Households are generally defined as individuals who purchase and prepare meals together. Applicants must be below certain income thresholds to be eligible for CalFresh. The food benefit amount a household receives is primarily based on household size, household income, and deductible living expenses. Figure 1 shows how these factors impact the amount of food benefits a household is eligible to receive. First, as shown in Figure 2 , households are eligible to receive food benefits up to a maximum amount that varies by household size—the more household members, the higher the amount of food benefits they are eligible to receive. Next, this maximum food benefit is adjusted downward to account for any income the household may have. A household’s income is calculated by adding up the earned income (such as wages and salaries) and unearned income (such as unemployment benefits) of all eligible household members. Finally, households can deduct a portion of their shelter, medical, and other living expenses from their income to calculate the income they have available to purchase food. Typically, food benefits increase as households have more deductible living expenses. (More detail concerning the CalFresh eligibility and benefit determination process is in the Appendix.)

Figure 2

CalFresh Maximum Food Benefit Amount Varies

by Household Sizea

|

Household Size |

Maximum Monthly Food Benefit Amount |

|

1 |

$192 |

|

2 |

352 |

|

3 |

504 |

|

4 |

640 |

|

5 |

760 |

|

6 |

913 |

|

7 |

1,009 |

|

Each additional person |

+144 |

|

aReflects 2017‑18 CalFresh maximum benefit levels. |

|

SSI/SSP

The SSI/SSP program provides monthly cash grants to low‑income aged, blind, and disabled persons. The 2017‑18 caseload is estimated to be 1.3 million recipients. Most SSI/SSP recipients are disabled adults or seniors (aged 65 years or older). The state’s General Fund provides the SSP portion of the grant while federal funds pay for the SSI portion of the grant. Federal law requires that the state maintain SSP monthly grant levels at or above March 1983 levels ($156 for individuals and $396 for couples). If SSP grants fall below these levels, the state risks losing its federal Medicaid funding.

In 2017, the maximum SSI/SSP monthly grant amount for aged and/or disabled individuals ($895) was below the federal poverty level (FPL)—at 89 percent of the FPL—while the maximum SSI/SSP grant amount for aged and/or disabled couples ($1,510) was above the FPL—at 112 percent of the FPL. SSI/SSP grant amounts are generally reduced dollar‑for‑dollar by a recipient’s income, meaning applicants with income in excess of the maximum SSI/SSP grant amount typically are not eligible to receive SSI/SSP benefits. The income of other household members generally does not offset a recipient’s SSI/SSP grant amount. This means that an individual SSI/SSP recipient may reside in a household with earned income from other household members that does not affect the SSI/SSP recipient’s grant—regardless of how much income the other household members have.

What Is the SSI Cash‑Out?

SSI Cash‑Out Makes SSI/SSP Recipients Ineligible for Federal Food Benefits. In 1974, states were given the option to increase monthly SSP grant payments by $10 (at the time the estimated average monthly food benefit for SSI/SSP recipients) in lieu of providing federal food benefits to this population. This effectively “cashed‑out” SSI/SSP recipients of their federal food benefits. California adopted the SSI cash‑out option, making SSI/SSP recipients ineligible for federal food benefits.

SSI Cash‑Out Was an Alternative Way States Could Provide Funding for Food to SSI/SSP Recipients and Reduce Food Stamp Administrative Costs. At the time the SSI cash‑out was implemented in California, the administrative cost to the state to provide federally funded food benefits to SSI/SSP recipients was significantly greater than the total amount of federal food benefits the state received for SSI/SSP recipients. At one point, it was estimated that the total costs of administering food benefits to SSI/SSP recipients in California would have been more than double the total amount of food benefits SSI/SSP recipients would have received absent the SSI cash‑out. The SSI cash‑out was a way to provide SSI/SSP recipients with a cash benefit that was roughly equivalent to the food benefit at the time, while avoiding the administrative costs of providing benefits through the CalFresh program.

The Federal Government Treats SSI Cash‑Out as a State Policy. Currently, California is the only remaining state in which the SSI cash‑out remains in place and SSI/SSP recipients are therefore ineligible for federal food benefits. It is our understanding that federal approval is not needed to end the SSI cash‑out. If the state decides to terminate its SSI cash‑out, the administration would only need to notify the federal government of the action. Additionally, California would have to end the SSI cash‑out for all households with SSI/SSP recipients. Although not required, some states that ended their SSI cash‑out also reduced the SSP grant by the $10 that was added in lieu of federal food benefits. We note that, in California, SSP grants could not be reduced by a full $10 because this would cause them to fall below the federal minimum grant level.

What Has Been the Effect of the SSI Cash‑Out?

The SSI Cash‑Out in California Has Affected Households With SSI/SSP Recipients Differently. Today, there are some households with SSI/SSP recipients that are worse off than they would be if the SSI cash‑out were not in place, and there are some households that are better off due to the SSI cash‑out than they otherwise would be. Below, we describe these different households and explain why the SSI cash‑out impacts them differently.

Pure SSI Households Are Worse Off Under the SSI Cash‑Out. Households that are disadvantaged under the SSI cash‑out are primarily composed solely of SSI/SSP recipients, referred to as “pure SSI households” for purposes of this report. Pure SSI households are composed of elderly or disabled nonelderly adults who live alone or with other SSI/SSP recipients. Under the SSI cash‑out, pure SSI households cannot receive CalFresh benefits even though their income (accounting for the $10 payment in lieu of federal food benefits) is low enough to meet the CalFresh eligibility requirements. In addition, in most cases, pure SSI households would be eligible to receive a higher amount of CalFresh benefits than the initial $10 payment provided to SSI/SSP recipients in lieu of federal food benefits. As a result, these households are worse off than they would be if the SSI cash‑out were not in place.

Effect of SSI Cash‑Out on Mixed SSI Households Varies. The effect of the SSI cash‑out on households that include both SSI/SSP and non‑SSI/SSP members—referred to as “mixed SSI households” for purposes of this report—is more complicated. Even though mixed SSI households include SSI/SSP recipients who are ineligible for CalFresh due to the SSI cash‑out, these households can still receive food benefits if the non‑SSI/SSP members meet the CalFresh eligibility requirements. As previously mentioned, the amount of food benefits a household receives primarily depends on two main factors that work in opposite directions—household size and income. Specifically, food benefits increase as household size increases, and food benefits decrease as household income increases. Under the SSI cash‑out, SSI/SSP recipients in mixed SSI households are excluded from the CalFresh eligibility and benefit calculation, meaning that SSI/SSP recipients are excluded from the household size calculation and the income of the SSI/SSP recipient is excluded from the total household income calculation. Below, we describe how these modifications to the CalFresh eligibility and benefit determination process effect mixed SSI households.

- Most Mixed SSI Households Receive More CalFresh Benefits Under the SSI Cash‑Out. For most mixed SSI households, the positive effect of excluding the income of SSI/SSP household members has a relatively greater impact on its food benefits than the negative effect of not including the SSI/SSP member(s) in the household size calculation. This means that the SSI cash‑out allows most mixed SSI households to receive more food benefits than they would otherwise receive if the income of the SSI/SSP member were included in the household income calculation, even after accounting for the decreasing effect on food benefits by not including the SSI/SSP member(s) in the household size calculation.

- A Small Portion of Mixed SSI Households Receive Fewer Food Benefits Under the SSI Cash‑Out. However, for some mixed SSI households, excluding the SSI/SSP member(s) from the household size calculation makes the household eligible for fewer food benefits. For these households, the gain in food benefits due to the exclusion of the income of SSI/SSP household members is relatively less than the loss in food benefits due to the exclusion of the SSI/SSP member(s) from the household size calculation. We note that this is typically the case for very low‑income, mixed SSI households.

Some SSI/SSP Recipients and Mixed SSI Households Are Not Affected by the SSI Cash‑Out. We note that some SSI/SSP recipients and mixed SSI households neither benefit nor lose under the SSI cash‑out. This is because some SSI/SSP recipients and mixed SSI households are ineligible for CalFresh for reasons other than the SSI cash‑out. For example, individuals who reside in an institution, such as a nursing home, are generally ineligible for CalFresh. This means that SSI/SSP recipients that reside in a nursing home are typically ineligible for CalFresh, regardless of whether the SSI cash‑out is in place. For purposes of the report, we focus on households that would experience a change in CalFresh eligibility or benefits as a result of ending the SSI cash‑out.

What Happens to Household Eligibility and CalFresh Benefits if the State Ends the SSI Cash‑Out?

SSI/SSP Recipients Become Factored Into CalFresh Eligibility and Benefit Calculation

If the SSI cash‑out is eliminated, SSI/SSP recipients would become eligible for CalFresh benefits. In effect, SSI/SSP recipients would be included in the CalFresh eligibility and benefit calculation, meaning the income of SSI/SSP recipients would count towards the total household income and SSI/SSP recipients would be included in the household size calculation. (We note that SSI/SSP recipients becoming eligible for and receiving CalFresh benefits would not change their SSI/SSP grant amount.)

Most Households Would See Food Benefits Increase, While Others Will Experience a Reduction. For some households, ending the SSI cash‑out would increase the amount of food benefits they receive today, while for other households ending the SSI cash‑out would decrease their current amount of food benefits. Generally, if the SSI cash‑out is ended, the resulting changes to the CalFresh eligibility and benefit calculation will affect households in one of the following ways:

- Become Newly Eligible for Food Benefits. By ending the SSI cash‑out, pure SSI households would become newly eligible for CalFresh benefits. Even though these households would become eligible for food benefits, it is likely that not all would choose to participate or enroll in CalFresh. (For example, a household may choose not to participate if they view the application process to be too burdensome.)

- Experience an Increase in Food Benefits. Ending the SSI cash‑out would make certain very low‑income, mixed SSI households eligible for increased food benefits primarily due to the increase in the calculated household size.

- Experience a Decrease in Food Benefits. For other mixed SSI households, their CalFresh benefits would decrease due to the additional countable income from the SSI/SSP household member(s).

- Become Ineligible for Food Benefits. For some mixed SSI households, including the income of SSI/SSP recipients would increase total household income over the CalFresh income eligibility thresholds, making them newly ineligible for food benefits.

Most Households With SSI/SSP Recipients Expected to Benefit From the Elimination of the SSI Cash‑Out. As shown in Figure 3, DSS estimates that if the SSI cash‑out is eliminated, almost three‑fourths of households with SSI/SSP recipients would benefit, either by becoming newly eligible for and participating in CalFresh or experiencing an increase in food benefits. However, some current CalFresh households would experience a reduction of food benefits if the SSI cash‑out were ended. We discuss these effects in detail below:

- Pure SSI Households Would Become Newly Eligible for CalFresh. The majority of households that would benefit from the elimination of the SSI cash‑out are pure SSI households that would become newly eligible for and participate in CalFresh benefits (369,000 households). (We note that DSS estimated that 123,000 households would become newly eligible for CalFresh but make the decision not to participate.) DSS estimated that newly eligible households that opt to participate in CalFresh would receive, on average, about $75 in monthly food benefits.

- Some Mixed SSI Households Would Experience an Increase in Food Benefits . . . DSS estimated that 6 percent, or 34,000 households, with SSI/SSP recipients currently receiving CalFresh benefits would experience, on average, a $97 increase in monthly food benefits if the SSI cash‑out were eliminated. This is primarily due to the inclusion of the SSI/SSP member(s) in the household size calculation—as household size increases, CalFresh benefits increase.

- . . . While Other Households Would Experience a Reduction in Food Benefits. As previously mentioned, ending the SSI cash‑out would require that the income of SSI/SSP members be included in the household income calculation. Given that CalFresh benefits are generally adjusted downward as households have more income, ending the SSI cash‑out would result in some CalFresh households receiving fewer food benefits. Of the households that would be negatively affected by the elimination of the SSI cash‑out, the majority of them would still be eligible for CalFresh, but are estimated to experience, on average, an $88 reduction in monthly food benefits (126,000 households). For some households currently receiving CalFresh benefits, including the SSI/SSP member(s) in the household income calculation would result in total household income exceeding the CalFresh income eligibility thresholds, meaning that the household would no longer be eligible to receive CalFresh benefits. It is estimated that 3 percent, or 14,000, of affected households with SSI/SSP recipients would become newly ineligible for CalFresh, losing, on average, about $150 in monthly food benefits.

Number of Households That Lose Food Benefits Could Be Lower Due to Elderly and Disabled Separate Household Rule. As previously stated, CalFresh benefits are provided to a household of individuals that purchase and prepare meals together. However, there is an exception to this rule. An elderly and disabled member living with others can become a separate CalFresh household even if they purchase or prepare meals with the other household members. To qualify for the elderly and disabled separate household rule, the income of the other household members cannot exceed 165 percent of the FPL. Currently, the application of the elderly and disabled separate household rule is infrequent and varies by county. This is in part because the use of this rule is not automatic, but requires a county worker to determine that a household would receive more CalFresh benefits if the elderly and disabled separate household rule were applied. It is our understanding that currently most households would not receive more CalFresh benefits from the application of the elderly and disabled separate household rule, which also contributes to its current infrequent use. However, if the SSI cash‑out is ended, this rule could potentially reduce the number of households that would lose food benefits as a result of including the SSI/SSP household member(s) in the CalFresh eligibility and benefit calculation.

Mathematica and DSS apply the elderly and disabled separate household rule to some but not all qualifying SSI/SSP households when estimating how households would be affected by ending the SSI cash‑out. Based on CalFresh and SSI/SSP administrative data, it would be reasonable to estimate that if the elderly and disabled separate household rule were applied to all qualifying households that would be negatively affected as a result of ending the SSI cash‑out, the number of households that would lose or become ineligible for CalFresh benefits could potentially decrease by roughly 7 percent, or 18,000 households.

Potential Administrative Challenges With Ending the SSI Cash‑Out

Elimination of the SSI cash‑out may create administrative challenges and costs for counties and the state. These challenges and costs primarily stem from (1) the initial enrollment of hundreds of thousands of previously ineligible SSI/SSP recipients in CalFresh and (2) the redetermination of eligibility and benefits for hundreds of thousands of currently participating CalFresh households. In addition, there would be ongoing challenges and costs associated with the maintenance of a larger CalFresh caseload. Recently, the state has implemented a streamlined CalFresh application and recertification process for elderly and/or disabled individuals, which may help with the enrollment of newly eligible SSI/SSP recipients. Any legislative efforts to streamline the CalFresh application process further in order to mitigate potential administrative challenges associated with ending the SSI cash‑out would most likely require input and/or approval from the federal government.

Statewide Net Effect of Ending the SSI Cash‑Out on CalFresh Benefits In California

In addition to understanding how ending the SSI cash‑out could potentially affect food benefits on a per household basis, it is helpful to consider the aggregate, statewide effect on the total food benefits received by California. We note that the statewide effect that ending the SSI cash‑out has on food benefits depends on a number of key assumptions, including (1) the number of households that would experience a change in eligibility or food benefits, (2) the amount of food benefits affected households gain or lose, and (3) the rate at which newly eligible households opt to participate in CalFresh. In 2010 and 2015, Mathematica conducted a study that simulated the effects of ending the SSI cash‑out in California. After accounting for all of the households they expected to gain and lose food benefits, as shown in Figure 4, Mathematica estimated a $3.5 million net positive impact on the amount of annual federal food benefits drawn down by the state following the elimination of the SSI cash‑out. In the spring of 2017, DSS modified Mathematica’s estimate to develop its own estimates of the effect of ending the SSI cash‑out on CalFresh benefits, estimating that ending the SSI cash‑out would increase the amount of annual federal food benefits received by the state by $205 million, on net. (We note that both Mathematica and DSS estimates are based on 2015 CalFresh program data. Any subsequent change in program rules, caseload, or food benefit amount will result in a different estimate of the net effect.)

Figure 4

Estimated Changes to Food Benefits and Administrative Costs Due to Ending the SSI Cash‑Out Vary

(In Millions)

|

Newly Eligible for CalFresha |

Still Eligible for CalFresh |

Newly Ineligible for CalFresh |

Net Total |

||

|

Increased Food Benefits |

Decreased Food Benefits |

||||

|

2015 Mathematica Estimates |

|||||

|

Change in Annual Federal Food Benefits |

$123.40 |

$39.40 |

‑$133.90 |

‑$25.50 |

$3.50 |

|

Change in Annual Nonfederal Administrative Costsb |

14.70 |

—c |

0.90 |

‑1.30 |

14.50 |

|

2017 DSS Estimates |

|||||

|

Change in Annual Federal Food Benefits |

325.30 |

39.40 |

‑133.90 |

‑25.50 |

205.40 |

|

Change in Annual Nonfederal Administrative Costsb |

38.70 |

—c |

$0.90 |

‑1.30 |

38.50 |

|

aReflects estimates of total federal food benefits received by newly eligible households expected to participate in CalFresh. bHistorically, counties pay 30 percent of the nonfederal CalFresh administrative costs and the state pays the remaining 70 percent. Additionally, these estimates reflect one‑time increases to CalFresh nonfederal administrative costs. Ongoing CalFresh nonfederal administrative costs would be lower. cLess than $500,000. DSS = Department of Social Services. |

|||||

Difference Between Mathematica’s and DSS’ Estimates Primarily Driven by Different Assumptions About Participation Rate for Newly Eligible Households. DSS largely based its estimates on Mathematica’s study with the exception of one key assumption—the CalFresh participation rate for newly eligible households. As previously stated, although ending the SSI cash‑out would make many SSI/SSP recipients eligible for CalFresh benefits, these individuals would still need to make the decision to participate in the program in order to receive food benefits. Although difficult to predict, the assumed participation rate in CalFresh for newly eligible households is a key factor that directly affects the amount of additional food benefits drawn down by the state. Specifically, DSS assumed a higher participation rate for newly eligible households (75 percent) than Mathematica (29 percent), resulting in a higher estimate of additional federal food benefits drawn down by the state as a result of ending the SSI cash‑out. Mathematica’s participation rate is based on the national average participation rate of all current CalFresh recipients who receive a food benefit amount that is similar to the amount of food benefit SSI/SSP recipients are expected to receive if the SSI cash‑out is ended. DSS instead based its participation rate on the national average participation rate of SSI/SSP recipients.

Net Increase to Food Benefits Partially Offset by Increased Administrative Costs. DSS estimates that ending the SSI cash‑out would increase administrative costs as counties process new CalFresh cases, redetermine eligibility and benefit amounts for existing CalFresh cases, and maintain a larger CalFresh caseload. The increase in administrative costs is primarily driven by the assumed number of newly eligible households that would participate in CalFresh—the more households that participate in CalFresh, the higher the administrative costs. Based on Mathematica’s and DSS’ estimates, it is estimated that the nonfederal share of CalFresh administrative costs would initially increase by about $15 million to $40 million. (We note that, historically, the counties’ share of nonfederal CalFresh administrative costs is 30 percent and the state’s share is the remaining 70 percent.) These costs primarily reflect the initial costs of enrolling newly eligible households into CalFresh and redetermining the eligibility and benefit amount of existing CalFresh households as a result of ending the SSI cash‑out. We note that the ongoing administrative costs associated with the elimination of the SSI cash‑out would be lower than the initial administrative costs.

Bottom Line: Actual Effect of Ending the SSI Cash‑Out Not Fully Known Until Policy Change Occurs. While we do not find the assumptions used by both Mathematica and DSS to be unreasonable, the actual effect of ending the SSI cash‑out may not be reflected in either estimate. That is, to the extent that key assumptions differ in actuality from initial estimates, the statewide net effect of ending the SSI cash‑out on food benefits could be different from these estimates. For example, for every percentage point that the participation rate for newly eligible SSI/SSP recipients is lower (or higher) than DSS’ initial estimate (75 percent), the estimated net amount of additional annual food benefits to the state decreases (or increases) by $4 million.

Finally, we note that the statewide net effect on food benefits is only one of many factors the Legislature could consider in deciding whether to end the SSI cash‑out. Other factors include a consideration of which individual households would experience an increase in federal food benefits and which households would experience a decrease in federal food benefits and how these households compare to one another in terms of income and resources. In the next section, we provide some examples of how ending the SSI cash‑out could impact households differently.

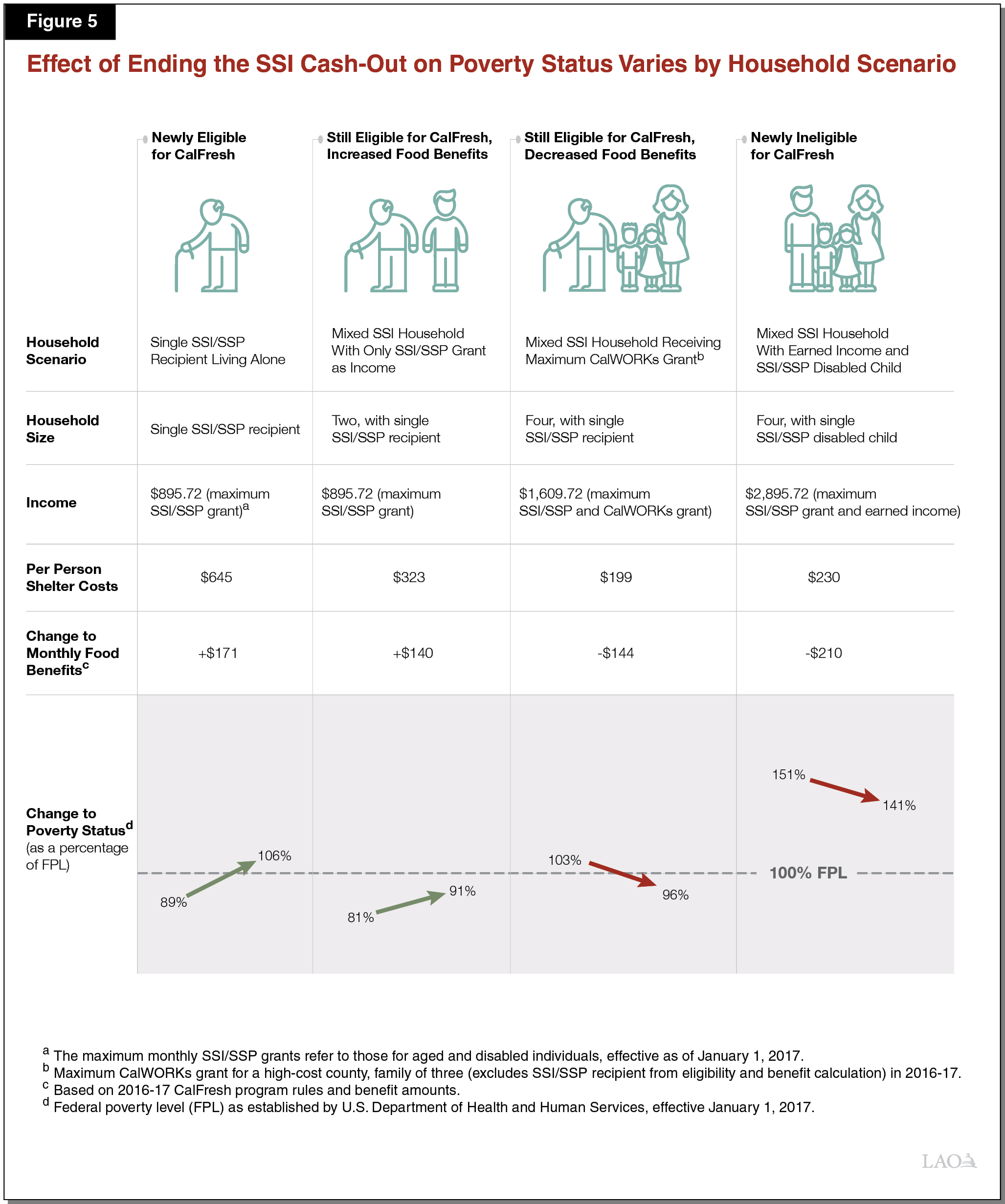

Examples Of Potential Impacts of Ending SSI Cash‑Out on Poverty

The SRL required that our office evaluate how ending the SSI cash‑out would affect the poverty status of households that would either gain or lose food benefits as a result. Given data constraints, we are unable to calculate the aggregate net impact of ending the SSI cash‑out on the poverty status of affected households. As an alternative, we developed four distinct household scenarios and simulated how the poverty status of each household would change if the SSI cash‑out were eliminated (see Figure 5). We utilized the previous Mathematica and DSS studies and CalFresh administrative data to identify common characteristics of households that would either gain or lose food benefits due to the elimination of the SSI cash‑out. We note that while the households we simulate could exist, we have no way of assessing exactly how common they would be in the current caseload. We found that ending the SSI cash‑out would place some households below the FPL while others would move above the FPL. Additionally, for some households, ending the SSI cash‑out would have little to no effect on their poverty status.

Below, we describe each sample household profile and the importance of deductible living expenses, income, and the elderly and disabled separate household rule in determining the effect of ending the SSI cash‑out on a household’s poverty status. We caution that these scenarios are for illustrative purposes and only apply to households that fit the household scenarios exactly, meaning any variation in assumed income, deductions, or household size would result in a different outcome. (We note that the eligibility and benefit calculation for these household examples is based on 2016‑17 CalFresh program rules.)

Scenario 1— Newly Eligible for Food Benefits: Single SSI/SSP Recipients Living Alone

It is estimated that the majority of households newly eligible for federal food benefits would consist of a single aged and/or disabled SSI/SSP recipient with income roughly equal to the maximum SSI/SSP grant ($895 for an individual SSI/SSP recipient). If it is assumed that an individual SSI/SSP recipient has monthly shelter costs of $645 and no deductible medical costs, by ending the SSI cash‑out this particular household would be eligible for $171 in food benefits. This would improve their poverty status from below the FPL (89 percent) to above the FPL (106 percent).

Food Benefits for Newly Eligible Households Are Highly Dependent on Medical and Shelter Costs. As previously mentioned, households can deduct certain living expenses, such as medical and shelter costs, from their income in determining food benefits. These deductions have the effect of increasing the amount of food benefits households are eligible to receive. For this particular household scenario, we assumed no deductible medical costs. However, if we assumed $120 in monthly medical deductions, the monthly food benefit amount for this particular household would increase from $171 to $194.

In addition, for this particular household scenario, we assumed $645 in monthly shelter costs. We chose this amount because survey data indicates that this is the average shelter cost for SSI/SSP renters and homeowners. However, if we assumed monthly shelter costs of less than $160 per month, the household would only receive the minimum food benefit amount of $16, resulting in only a slight improvement in their poverty status to about 93 percent of the FPL. If monthly shelter costs exceeded $750, the household would receive the maximum food benefit amount of $194, changing their poverty status to 108 percent of the FPL. (We note that the minimum food benefit amount decreased from $16 in 2016‑17 to $15 in 2017‑18 and the maximum food benefit amount for a household of one decreased from $194 in 2016‑17 to $192 in 2017‑18.) We note that survey data indicate that roughly 40 percent of SSI/SSP recipients are homeowners, some with no mortgage payments (meaning they have little to no shelter costs). As a result, we anticipate that a portion of newly eligible households would have little to no deductible shelter costs, receive the minimum food benefit amount ($16), and therefore remain below the FPL. Additionally, to the extent that newly eligible households receive assistance paying their shelter costs (either by relatives or through a public assistance program), this would also reduce their shelter costs and therefore their food benefit amount.

Scenario 2— Still Eligible, Increased Food Benefits: Mixed SSI Household With Only SSI/SSP Grant as Income

A small percentage of mixed SSI households could qualify for an increased food benefit if the SSI cash‑out is ended. Estimates show that mixed SSI households with no countable income besides the SSI/SSP grant payment are one of the most common types of mixed SSI households that would receive increased food benefits if the SSI cash‑out were eliminated. This could be the case for a low‑income household in which the non‑SSI household member recently lost their job and is in the process of applying to other public assistance programs.

To illustrate this point, we modified the previous household example of a single SSI/SSP recipient to also include one non‑SSI/SSP household member with no countable income. Additionally, we assume the same total monthly shelter costs as Scenario 1 ($645 total or about $323 per person) and no medical deduction. Under the SSI cash‑out, this household could receive monthly food benefits through the non‑SSI/SSP household member who has no income. In that case, the household would receive $194 in monthly food benefits, the maximum food benefit amount for a household of one. Combined with the SSI/SSP grant payment, the household’s total monthly resources would be about $1,170, which is 81 percent of the FPL. If the SSI cash‑out were eliminated and the SSI/SSP recipient were included in the CalFresh household size and income calculation, the household would receive $334 in monthly food benefits—increasing the monthly food benefit to this household by $140 and changing the household’s poverty status from 81 percent of the FPL to 91 percent of the FPL. In this case, the increase in household size increased the food benefit amount more than the additional income from the SSI/SSP recipient reduced it.

Food Benefits Would Decrease as Household Income Increases. If the non‑SSI/SSP household member with no income in this example were to instead have income, the household’s food benefit would be less than $334. This is because the amount of food benefits a household is eligible to receive generally decreases as household income increases.

Scenario 3— Still Eligible, Decreased Food Benefits: Mixed SSI Household Receiving Maximum CalWORKs Grant

Unlike the previous examples, for an estimated 23 percent of affected households, ending the SSI cash‑out would reduce their food benefit amount. Estimates show that the majority of these households who would experience a decrease in food benefits have income other than the SSI/SSP grant, often in the form of other public assistance benefits, such as California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs). (This program provides cash grants and welfare‑to‑work services for families whose income is inadequate to meet their basic needs.) For example, ending the SSI cash‑out would decrease the monthly food benefit by $144 for a household of four who is currently receiving the maximum CalWORKs grant and has one family member on SSI/SSP. In these cases, the additional income of the SSI/SSP recipient reduced the level of food benefit far more than the increase in household size raised it. This scenario assumes monthly shelter costs of about $200 per person ($800 total) and no deductible medical costs. For this particular household, the decrease in monthly food benefits would change their poverty status from above (103 percent) to below the FPL (96 percent).

Elderly and Disabled Separate Household Rule Could Reduce the Negative Effects of Ending the SSI Cash‑Out in Certain Circumstances. As previously noted, under certain conditions, an elderly and disabled SSI/SSP recipient could become a separate CalFresh household even if they purchase or prepare meals with other household members. For this particular household profile, if the SSI/SSP recipient were elderly and disabled, and the rest of the household had income at or below 165 percent of the FPL, this rule could allow the household to be treated as two separate households for purposes of determining CalFresh eligibility. In effect, this would make it so the SSI/SSP recipient is treated as a pure SSI household (similar to Scenario 1), and the other members of the household see no change in their monthly food benefit amount as a result of ending the SSI cash‑out.

Scenario 4— Newly Ineligible for Food Benefits: Mixed SSI Household With Earned Income and an SSI/SSP Disabled Child

Ending the SSI cash‑out would make some mixed SSI household currently receiving CalFresh ineligible for CalFresh benefits. For these households, including the SSI/SSP grant payment in the income calculation for CalFresh eligibility would increase their income beyond the CalFresh income eligibility thresholds, making them ineligible to receive food benefits. Mathematica and DSS estimates show that one of the more common types of households that would become ineligible for food benefits would be mixed SSI households with income above the FPL. To illustrate this scenario, we consider a household of four with about $3,000 in total household income ($2,000 monthly earned income and $895 SSI/SSP grant payment). In addition, we assume the household has one SSI/SSP disabled child receiving the maximum SSI/SSP monthly grant payment, $230 in per‑person monthly shelter costs ($920 total), and no deductible medical costs. Under current CalFresh program rules, this household would receive $210 in monthly food benefits. By ending the SSI cash‑out, the household would no longer be eligible for food benefits. Even though the household would lose all their food benefits, their poverty status would remain above the FPL (although dropping from 151 percent to 141 percent).

We note that newly ineligible households with different characteristics may experience a smaller or greater loss in monthly food benefits as a result of the elimination of the SSI cash‑out. For example, if this same household had total earned income of $2,500, it would lose $30 in monthly food benefits as a result of ending the SSI cash‑out. The loss in food benefits would have a relatively small impact on their poverty status—changing from 167 percent of the FPL to 166 percent of the FPL.

Bottom Line: Households That Benefit Most From Ending SSI Cash‑Out Have Relatively Less Income Than Those Who Experience Food Benefit Reductions

As these scenarios illustrate, there are many factors that determine how a household’s food benefit is calculated. Changes in a household’s income, size, and medical and shelter costs can have significant impacts on its food benefit amount. Making SSI/SSP recipients eligible for food benefits generally results in an improvement in the poverty status for households with the lowest income, while households with relatively higher income are more likely to experience a reduction. Although some households with SSI/SSP recipients are expected to lose benefits, they would receive the same amount of food benefits as a similar household of the same household size, income, and deductible living expenses that do not have an SSI/SSP recipient. This is because ending the SSI cash‑out would apply the same CalFresh eligibility and benefit determination process to all households, regardless of whether the household includes an SSI/SSP recipient. We note, however, that even households that are expected to lose food benefits as a result of ending the SSI cash‑out, although relatively higher income than those who are expected to experience increased food benefits, are not necessarily far above the FPL.

Legislative Options for Holding Households Harmless

For households that will experience a reduction in food benefits as a result of ending the SSI cash‑out, the SRL requires that we provide potential hold harmless options and assess the administrative complexity and cost of each option. As we have shown, DSS estimates that if the SSI cash‑out ends, there would be approximately 140,000 households that are expected to experience a loss in food benefits. In total, these households are estimated to lose about $160 million in federal food benefits. A hold harmless policy would create a state‑funded food program that would aim to backfill all, or a portion of, these lost federal food benefits. (We note that holding negatively affected households with SSI/SSP recipients harmless would mean that these households would, in effect, continue to receive more food benefits than households with no SSI/SSP recipients but with the same household size, income, deductible living expenses, and poverty status.) The main factors the Legislature may wish to consider when constructing a hold harmless policy following the elimination of the SSI cash‑out include:

- Who Is Eligible? Who would be eligible for the hold harmless policy? Would all individuals negatively affected by the end of the SSI cash‑out be eligible? Or would it only be available to a subset of those negatively impacted? Would the policy only be available to those in the program when the SSI cash‑out ends, or would it also be available to future households? The more individuals eligible for the hold harmless policy, the more costly the policy will be.

- What Is the Duration of a Hold Harmless Policy? How long would the hold harmless policy be in effect? Would it be for a limited amount of time? Or until the person naturally exits the program? The longer the hold harmless policy is in place, the more costly the policy will be.

- What Is the Benefit Amount? Should households receive the same amount of benefits they received prior to ending the SSI cash‑out or some other, potentially lower, fixed benefit amount? For more long‑term hold harmless policies, would the benefit amount adjust if households experience a change, such as an increase in income? The higher the benefit amount, the more costly the hold harmless policy will be.

- How Administratively Complex Is the Hold Harmless? How complicated would it be—for both recipients and counties—to implement the hold harmless policy? What are the potential automation costs? What are the potential impacts on county workload?

Below, we present hold harmless policy examples that range in cost and administrative complexity. First, we provide rough estimates of the benefit costs of the policies and then we describe the potential automation and administrative costs. For the estimated cost of the various hold harmless policies below, we rely on DSS estimates of the total amount of federal food benefits lost by the state if the SSI cash‑out is ended. As we have noted, these estimates are subject to uncertainty and may change in future years as the caseload and benefit levels change. For all examples, the benefit and automation costs are rough estimates based on hypothetical program models and would change following further clarity on actual program structure.

Benefit Costs of Various Hold Harmless Policies

Example 1: Provide a Short‑Term Food Benefit to Existing Population. When considering various hold harmless policies, the Legislature could consider creating a temporary state‑funded food benefit program for households negatively affected by the elimination of the SSI cash‑out. The program could provide households with a fixed level of food benefits, meaning that the state food benefit would not change even if a household experienced a change in income or household size. Additionally, the state food benefit would be provided over a fixed amount of time. For example, for a period of six months, households could receive state food benefits equivalent to the amount of federal food benefits they lost as a result of ending the SSI cash‑out. To simplify the administration of this option, the benefit level would remain fixed for the duration of the hold harmless policy, meaning the benefit amount would not change in the six‑month period. Only households receiving CalFresh benefits at the time of the effective elimination date of the SSI cash‑out would qualify for the state‑funded food benefit program. Once the hold harmless time period expires, all households would be subject to the standard CalFresh rules. In other words, following the expiration of the state program, previously held harmless households would either become ineligible for or receive fewer CalFresh benefits.

As shown in Figure 6, this example of a hold harmless policy would result in state costs of roughly $80 million to $100 million. The policy would cost more (or less) if the duration of the benefit is longer (or shorter). Additionally, policy costs would be lower if households only received a portion (for example, one‑half) of the food benefits they lost due to the elimination of the SSI cash‑out.

Figure 6

Example 1: Short‑Term Food Benefit for Existing Population

|

|

|

|

Estimated Cost: $80 million to $100 million. |

Example 2: Provide a Long‑Term Food Benefit to Existing Population. The Legislature could also consider implementing a state‑funded food program for existing households that experience a reduction in federal food benefits as a result of the ending the SSI cash‑out with no defined end date. The state program could mirror the program structure and rules of CalFresh today—when the SSI cash‑out is in place—meaning that the eligibility and benefit calculation would continue to exclude SSI/SSP household members for those mixed SSI households that were better off under the SSI cash‑out. Similar to Example 1, only currently participating households that would be negatively affected by the elimination of the SSI cash‑out would receive state food benefits.

Unlike Example 1 where the benefit amount would be fixed, in this example, the benefit amount would be adjusted for any household changes, such as income—similar to how the CalFresh program works today. A household would continue to receive state food benefits as long as it (1) continued to be eligible for CalFresh if the SSI cash‑out were not eliminated, and (2) would have received more CalFresh benefits if the SSI cash‑out were in place. If a household failed to meet one of the two aforementioned conditions, the household would exit the state‑funded hold harmless program and would instead receive federal food benefits through the CalFresh program. Households would not be able to cycle in and out of the state program, meaning that once removed from the state program, households could not reapply to receive state food benefits at a later date. As shown in Figure 7, based on DSS estimates, the cost of this hold harmless policy could be in the range of $160 million to $200 million annually—which would decrease over time as individuals naturally exit the program.

Figure 7

Example 2: Long‑Term Food Benefit for Existing Population

|

|

|

|

Estimated Cost: $160 million to $200 million, declining over time. |

Example 3: Provide a Long‑Term Food Benefit to Existing and Future Populations. This option would establish a permanent state‑funded food benefit program for all current and future households that would have received more federal food benefits under the SSI cash‑out. The program rules and benefit calculation would be the same as Example 2, with the exception that the program would be available to both current households and future households. Of all the examples presented here, this would likely be the most costly policy for the state. As shown in Figure 8, initial benefit costs would be about $160 million to $200 million annually (similar to Example 2). However, because the program would be open to future households that would have been better off if the SSI cash‑out would have remained in place, costs would not decline over time.

Figure 8

Example 3: Long‑Term Food Benefit for Existing and Future Populations

|

|

|

|

Estimated Cost: $160 million to $200 million, with unknown costs in future years. |

Example 4: Create a Narrowly Targeted Hold Harmless Program. Finally, one option the Legislature may wish to consider is implementing a hold harmless policy for only a subset of mixed SSI households who are negatively affected by ending the SSI cash‑out. For example, the Legislature could target the hold harmless policy only to families that fall below the FPL as a result ending the SSI cash‑out. Another example would be to target the hold harmless policy to those participating in other public assistance programs. As shown in Figure 9, after choosing the more narrow population to target, the Legislature would still have to make the decisions related to benefit amount and duration as in the prior examples. The cost of this targeted hold harmless policy is unknown at this time, but would likely be less than the other examples we have shown.

Figure 9

Example 4: Narrowly Targeted Hold Harmless Program

|

|

|

|

Estimated Cost: Unknown, but likely lower than the other hold harmless examples. |

The Elderly and Disabled Separate Household Rule Could Reduce Costs for All Options. As previously noted, an elderly and disabled SSI/SSP recipient could become a separate CalFresh household unit if the income of other household members is less than 165 percent of the FPL. By becoming a separate household, the elderly and disabled SSI/SSP recipient and his/her SSI/SSP grant would not be included in the CalFresh eligibility and benefit calculation for the other household members, meaning the food benefits for other household members would remain the same. In effect, use of this administrative rule could allow a portion of households that would either become ineligible for or experience a reduction in CalFresh benefits if the SSI cash‑out were eliminated to remain in the CalFresh program and continue to receive the same amount of federal food benefits. Based on CalFresh and SSI/SSP administrative data, it would be reasonable to estimate that the elderly and disabled household rule could apply to roughly 18,000 mixed SSI households if the SSI cash‑out were eliminated, potentially reducing the state costs of any hold harmless policy (including those in the examples above) by roughly $10 million to $20 million.

Potential Administrative Cost and Complexity of Hold Harmless Policies

In addition to the benefit costs described above, all of the examples of hold harmless policies that we provide would have additional automation and state and county administrative costs that should be considered. These costs would depend on the complexity of the hold harmless policy that is adopted. For example, a hold harmless policy that includes a fixed benefit for a fixed amount of time (such as Example 1) would likely have the lowest administrative and automation costs. A policy that includes a variable benefit level for current and future households (similar to Example 3) would likely be relatively more expensive, as it would require more sophisticated automation and workload to track households over a longer period of time. In any case, it is possible that the initial automation and administration of any hold harmless policy could range from the low millions of dollars for a relatively simple policy to the low tens of millions of dollars for a more complex policy, with relatively lower costs in the out years. In addition, there would be ongoing administrative costs, primarily driven by the number of participating households.

Additional Issues for Legislative Consideration

Prior to making a decision to end the SSI cash‑out in California and implement a hold harmless policy, there are several key issues that merit further consideration by the Legislature. Primarily, there are trade‑offs to both keeping or eliminating the SSI cash‑out. Currently, under the SSI cash‑out, individual SSI/SSP recipients cannot receive CalFresh benefits even though their income is low enough to meet the CalFresh eligibility requirements. Although ending the SSI cash‑out would make these SSI/SSP recipients eligible to receive CalFresh benefits, it would result in some households losing CalFresh benefits. Below we present additional issues for the Legislature to consider when deciding whether to eliminate the SSI cash‑out.

- Can More Up‑to‑Date Estimates Be Developed? As we have noted throughout this report, due to data limitations, there are significant challenges associated with estimating the effect of ending the SSI cash‑out on the amount of food benefits received by households with SSI/SSP recipients. It is also difficult to estimate the statewide net impact ending the SSI cash‑out would have on total food benefits received by California. Prior to a decision to end the SSI cash‑out, the Legislature should ask DSS if there is any way to further refine and increase confidence in its most recent estimates.

- How Could Potential Administrative Challenges for Counties and the State Be Mitigated? Ending the SSI cash‑out and implementing a hold harmless policy both present significant administrative costs and challenges for the state and counties. Are there ways to reduce these challenges? For example, what would the timeline for implementation be? Is there a way to phase in the enrollment of newly eligible households into the CalFresh program prior to the elimination of the SSI cash‑out in order to reduce the administrative burden?

- Are There Ways to Further Simplify the CalFresh Application Process? Although ending the SSI cash‑out makes SSI/SSP recipients eligible for CalFresh, they still need to apply for the benefit. The department has recently received federal approval for a more streamlined application and redetermination process for elderly and/or disabled recipients. In order to increase participation rates, the Legislature may wish to consider whether there are more steps the state could take to increase the likelihood that newly eligible SSI/SSP recipients actually apply for CalFresh benefits. We note that attempts to change the CalFresh application process would most likely require approval by the federal government.

- Are There Challenges Associated With Utilizing the Elderly and Disabled Separate Household Rule? As previously mentioned, the elderly and disabled separate household rule is infrequently used. The Legislature could request the following information from the administration to fully understand the benefits and potential challenges of using the elderly and disabled separate household rule as a way to reduce the costs associated with a hold harmless policy: (1) the number of negatively affected households that could be held harmless by the separate household rule, (2) current and potential future administrative challenges for counties in applying the separate household rule if the SSI cash‑out were eliminated, (3) administrative costs, and (4) how requiring the use of the elderly and disabled separate household rule could affect other CalFresh rules for elderly and/or disabled applicants.

- Would Ending the SSI Cash‑Out Affect Other Public Assistance Programs? It is our understanding that ending the SSI cash‑out to enable SSI/SSP recipients to receive CalFresh benefits would have no effect on one’s eligibility for, and amount of, the SSI/SSP or CalWORKs grant. However, it is unclear if providing state‑funded food benefits would affect an individual’s ability to qualify for and receive other forms of public assistance. The Legislature should ask the department if ending the SSI cash‑out and establishing a hold harmless program would affect an individual’s eligibility for, or amount of, benefits received from other public assistance programs.

Conclusion

The decision of whether to end the SSI cash‑out involves trade‑offs. The majority of households with SSI/SSP recipients would benefit from the elimination of the SSI cash‑out. However, some households currently receiving CalFresh benefits would either experience a decrease in food benefits or become ineligible for CalFresh. While negatively affected households generally have limited financial means, they tend to have more income than households that would benefit from ending the SSI cash‑out. The Legislature could consider establishing a state food benefit program that would replace some or all of the lost food benefits. There are many ways a state food benefit program could be structured, each with its own trade‑offs. In addition, depending on how the hold harmless program is structured, and other key policy decisions, state and county costs and administrative complexity could vary.

Appendix: CalFresh Eligibility and Benefit Calculation

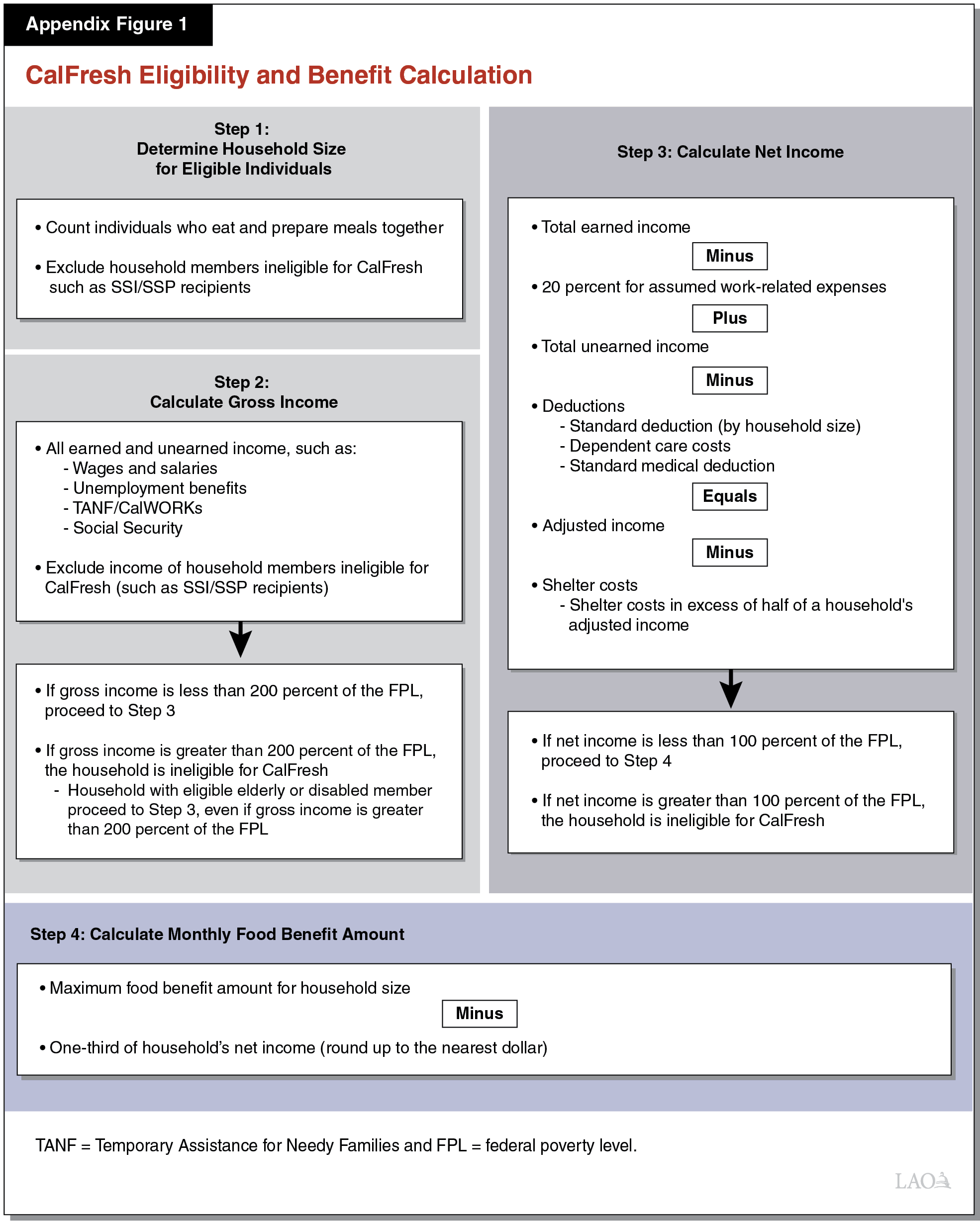

In Appendix Figure 1 , we walk through the steps to determine whether a household is eligible for food benefits and, if so, how much food benefits the households would receive. We also discuss how the CalFresh eligibility and benefit determination process would change if the SSI cash‑out were eliminated.

Step 1: Determine Household Size of Eligible Individuals. The first step in determining a household’s eligibility and CalFresh benefit amount is calculating their household size of eligible individuals. This is necessary because the CalFresh benefit amount varies by household size, increasing with every additional household member. Households are generally defined as individuals who purchase and prepare meals together. Individuals must meet several eligibility criteria to be found eligible for CalFresh benefits. For example, Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Payment (SSI/SSP) recipients are ineligible for CalFresh benefits. Eligible household members can receive CalFresh benefits even if the household includes ineligible members, such as an SSI/SSP recipient. In practice, household members ineligible for CalFresh are excluded from the CalFresh eligibility and benefit calculation. This means that members ineligible for CalFresh are not included in the household size calculation for purposes of determining the household’s CalFresh benefit amount.

Step 2: Calculate Gross Income. After determining household size of eligible individuals, the next step is to calculate a household’s gross income, one of two income requirements within the CalFresh benefit and eligibility determination process. Typically, households are required to have gross income below 200 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). Gross income is defined as earned and unearned income, including wages and salaries, alimony, social security, and workers’ compensation. The income of ineligible CalFresh members is excluded from the gross income calculation. If a household has gross income less than 200 percent of the FPL, they pass the gross income requirement and proceed to Step 3. However, if a household has gross income greater than 200 percent, they fail the gross income requirement and therefore are ineligible for CalFresh. We note that households with an eligible elderly or disabled member (who is not an SSI/SSP recipient) are exempt from the gross income requirement, meaning even if they have gross income above 200 percent of the FPL, the households could continue on to Step 3.

Step 3: Calculate Net Income. If a household passes the gross income requirement, they proceed to the second income requirement—having net income that is generally less than 100 percent of the FPL. A household’s net income is intended to represent the income they have available to purchase food. To calculate the net income, a household’s earned income is first reduced by 20 percent for assumed work‑related expenses. Next, the household’s unearned income is added to this amount. Finally, the net income is adjusted downward to account for any deductions. (We note that the income of and living expenses paid by household members ineligible for CalFresh are excluded from the net income calculation.) All households receive a standard deduction, which varies by household size. Additional deductions include:

- Dependent Care Costs. Households can deduct child or other dependent care costs from their gross income to determine their net income. The care must be necessary to allow a household member to accept or continue to work, or to attend training or schooling that prepares the person for work. There is no cap on dependent care deductions.

- Standard Medical Deduction. A household with at least one eligible elderly (aged 60 years or older) and/or disabled member can deduct that member’s non‑reimbursed medical expenses. As of October 1, 2017, elderly and/or disabled households with monthly medical expenses between $35 and $155 qualify for the standard medical deduction, meaning they can deduct $120 per month from their gross income. Households with monthly medical expenses greater than $155 can deduct actual medical expenses.

- Shelter Costs. Households can deduct monthly shelter costs that exceed 50 percent of their adjusted income. Shelter costs include rent, mortgage payments, taxes and insurance on the home, and utilities. The maximum shelter deduction in federal fiscal year 2017‑18 is $535 unless there is an eligible elderly and/or disabled household member—there is no cap on deductible shelter costs for these households.

After applying all the applicable deductions, if a household’s net income is less than 100 percent of the FPL they would be eligible to receive CalFresh benefit and proceed to Step 4. However, if a household’s net income exceeds 100 percent of the FPL, they would generally be ineligible for CalFresh benefits.

Step 4: Calculate Monthly Food Benefit Amount. If a household is found eligible, a household’s net income is used to calculate the amount of monthly food benefits they will receive. This means that households receive food benefits up to a maximum amount based on household size, which is adjusted downward by one‑third of a household’s net income. For example, a household of four with zero net income would receive $640 in CalFresh benefits, the maximum food benefit amount for a household of four. Maximum food benefit amounts are set by the federal government and are generally adjusted on an annual basis to reflect changes in the price of food. In 2017‑18, the minimum food benefit amount for a one‑ and two‑person household is $15.

CalFresh Eligibility and Benefit Determination Process Would Change if SSI Cash‑Out Is Eliminated. Given that SSI/SSP recipients are currently ineligible for CalFresh, they are currently excluded from the CalFresh eligibility and benefit calculation. For households with a mix of SSI/SSP recipients and non‑SSI/SSP recipients this means that SSI/SSP recipients are excluded from the household size, gross income, and net income calculation. Additionally, any deductible living expenses paid for by the SSI/SSP recipient, such as shelter or medical costs, are not included in the eligibility and benefit calculation. If the SSI cash‑out is eliminated, SSI/SSP recipients would become newly eligible for CalFresh benefits, meaning households would be required to include SSI/SSP members in the household size, gross income, and net income calculations.