Summary

On January 13, the Governor released California’s Five–Year Infrastructure Plan, the first statewide infrastructure plan released by the administration since 2008. The plan proposes state spending on infrastructure projects through 2018–19. In this brief, we review the administration’s plan and commend the administration’s renewed focus on infrastructure. We also find that the plan raises some important policy issues related to the financing and maintenance of state infrastructure and serves as a valuable starting point for legislative discussions. We also note, however, that the plan does not include some key information and suggest some changes that could make the plan more helpful to the Legislature.

In addition, given the size of the state’s infrastructure investments and their long–term nature, we recommend that the Legislature take a more active role in considering infrastructure in a comprehensive way. In order to assist the Legislature, we suggest some broad questions it may find helpful in guiding future discussions, such as how best to determine the state’s long–term policy and infrastructure goals, how the state should prioritize competing infrastructure needs, and what policy changes have the potential to reduce demand for new infrastructure. We further suggest that the Legislature consider how, as an institution, it addresses infrastructure issues—for example, by creating a joint infrastructure committee.

As shown in Figure 1, the state’s major infrastructure includes a diverse array of capital facilities associated with the following program areas: transportation, higher education, water resources, natural resources, criminal justice, health services, and general government office space.

In addition to the state government infrastructure investments shown in Figure 1, the state has historically provided funds for local public infrastructure. These include such areas as K–12 school construction, community college construction, local streets and roads, local parks, wastewater treatment, flood control, and county jails.

Figure 1

Major State Infrastructure

|

Transportation

|

- More than 50,000 miles of highway and freeway lanes.

- 7.8 million square feet of Department of Transportation offices, shops, materials laboratories, and maintenance facilities.

- 170 Department of Motor Vehicles offices.

- 103 California Highway Patrol area offices.

|

|

Criminal Justice

|

- 34 prisons and 42 correctional conservation camps.

- 4 youthful offender institutions (3 facilities and 1 conservation camp).

- Roughly 20 million square feet managed by the judicial branch.

- 11 crime laboratories.

|

|

Water Resources

|

- 34 storage facilities, lakes, and reservoirs.

- 20 pumping plants.

- 4 pumping–generating plants.

- 5 hydroelectric power plants.

- 700+ miles of canals and pipelines—State Water Project.

- 1,595 miles of levees and 55 flood control structures in the Central Valley.

|

|

Natural Resources

|

- 280 state park units containing 1.6 million acres and over 4,400 miles of trails.

- Over 500 CalFire facilities (including 228 forest fire stations, 39 fire/conservation camps, and 13 air attack bases).

- 16 agricultural inspection stations.

|

|

Higher Education

|

- 10 University of California campuses.

- 23 California State University campuses.

|

|

Health Services

|

- 5 mental health hospitals.

- 4 developmental centers.

|

|

General State Office Space

|

- 556 state–owned office structures covering 23 million square feet.

- 941 leases for 13 million square feet of state office space.

|

Recently, there has been renewed interest in California for additional investments in infrastructure, particularly because of aging facilities and roads, as well as an ever–increasing state population. However, the state faces many competing priorities for funding as it emerges from recession—including paying down budgetary liabilities, addressing long–term liabilities, building a reserve, and restoring cuts to various state programs. As the state faces these difficult choices, it is especially important for it to have an effective infrastructure planning and decision–making process that includes well–conceived, timely, and comprehensive infrastructure plans as well as active legislative engagement.

Significant Infrastructure Demands. Much of the state’s immense stock of existing infrastructure is aging and in need of repair or replacement. For example, four out of five state hospitals and about 70 percent of the Department of Forestry and Fire Protection’s forest fire stations are more than 50 years old. In many cases, the state has under–invested in routine maintenance and repairs, resulting in further deterioration of facilities. For example, the California Department of Transportation estimates that 16 percent of the state’s highway lane miles are in poor condition. As discussed in more detail below, the administration has identified about $65 billion worth of projects resulting from state agencies having deferred routine and preventive maintenance in the past. Furthermore, the state population continues to grow—the administration currently estimates that it will reach 50 million by 2050—which drives additional demands on infrastructure.

Infrastructure Planning Is Fragmented. Historically, the state’s infrastructure planning and decision–making processes have been very fragmented. Most infrastructure planning occurs in individual state departments. Departments often develop internal assessments of their infrastructure needs, as well as develop planning documents designed to address their highest infrastructure priorities. If approved by the Department of Finance (DOF), proposals for funding these priorities are heard in different budget subcommittees, depending on the particular program areas. In addition, most large infrastructure projects are often financed with bonds, which are focused on specific program areas (such as transportation or higher education). In some cases, these bond measures are approved by the Legislature, typically through the policy committee process, and in other cases, the measures are put on the ballot directly by voters through the initiative process. Consequently, infrastructure proposals are routinely reviewed, debated, and funded separately and through differing processes, depending on the circumstances of the specific proposals. It is sensible to make many infrastructure decisions within policy areas since infrastructure investments are frequently driven by specific programmatic needs. However, these compartmentalized decision–making processes can also make it difficult for the Legislature to effectively assess—from a statewide perspective—the trade–offs of different projects or proposals across policy areas.

Previously, the Legislature recognized the challenges posed by having this compartmentalization of infrastructure planning and decision making. In 1999, the Legislature passed Chapter 606, Statutes of 1999 (AB 1473, Hertzberg), to require the administration to consolidate planning information into a statewide infrastructure plan to be released annually with the Governor’s January budget proposal. The purpose of the requirement is to ensure that the Legislature has a regularly updated, centralized compilation and prioritization of projects across programs to better assess the range and scale of the state’s infrastructure needs, as well as to determine its own funding priorities.

Infrastructure Investments Are Often Large and Long Term. The state’s fragmented approach to infrastructure planning and decision making is especially problematic because infrastructure investments typically involve large expenditures—with even small state projects costing millions of dollars and bond proposals typically totaling billions of dollars. Since 2000, the voters have authorized roughly $96 billion in new general obligation bonds. Furthermore, infrastructure choices have long–term implications as they are often funded with debt that is repaid over 25 or 30 years. This debt is typically repaid using the state’s General Fund, which also funds state programs like education, corrections, and health and human services. Consequently, the funding choices of today have cost implications on the funds available for other state programs for decades.

Capital Infrastructure Proposal. California’s Five–Year Infrastructure Plan presents the administration’s infrastructure funding priorities. The plan identifies about $57 billion in capital infrastructure funding in the period from 2014–15 through 2018–19. As shown in Figure 2, the bulk of these expenditures ($53 billion) is for transportation, split roughly equally between the state’s high–speed rail project and other transportation projects. The remaining capital spending identified in the plan is proposed in the areas of criminal justice, natural resources, education, health and human services, and general government. The plan does not include funding that was appropriated in previous years (even if it will be spent within the five–year period) or state funding for most types of local infrastructure (such as local streets and roads). Thus, the administration’s plan is not currently designed to be a comprehensive tally of the state’s spending on infrastructure from 2014–15 through 2018–19.

Figure 2

Administration’s Capital Outlay Proposal

(All Funds, in Millions)

|

Program Area/

Department

|

Proposed Amount

|

|

2014–15

|

2015–16

|

2016–17

|

2017–18

|

2018–19

|

Total

|

|

Transportation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Caltrans

|

$6,209.0

|

$5,256.0

|

$5,344.0

|

$5,304.0

|

$5,312.0

|

$27,425.0

|

|

High–Speed Rail Authority

|

250.0

|

25,331.0

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

25,581.0

|

|

Other

|

1.7

|

28.7

|

52.9

|

164.2

|

164.2

|

411.7

|

|

Subtotals

|

($6,460.7)

|

($30,615.7)

|

($5,396.9)

|

($5,468.2)

|

($5,476.2)

|

($53,417.7)

|

|

Criminal Justice

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Judicial Branch

|

$162.5

|

$103.0

|

$946.6

|

$83.5

|

—

|

$1,295.6

|

|

Corrections and Rehabilitation

|

157.6

|

126.5

|

21.8

|

11.7

|

$59.4

|

377.0

|

|

Subtotals

|

($320.1)

|

($229.5)

|

($968.4)

|

($95.2)

|

($59.4)

|

($1,672.6)

|

|

Natural Resources

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conservancies

|

$191.0

|

$136.0

|

$112.0

|

$110.0

|

$90.0

|

$639.0

|

|

Water Resources

|

113.5

|

58.2

|

8.1

|

—

|

—

|

179.8

|

|

Other

|

59.3

|

11.5

|

36.4

|

57.8

|

109.5

|

274.6

|

|

Subtotals

|

($363.8)

|

($205.7)

|

($156.5)

|

($167.8)

|

($199.5)

|

($1,093.4)

|

|

Education

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

State Special Schools

|

—

|

$7.5

|

$31.0

|

$46.0

|

$41.6

|

$126.2

|

|

California State University

|

$5.8

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

5.8

|

|

Community Colleges

|

19.2

|

80.1

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

99.3

|

|

Subtotals

|

($24.9)

|

($87.6)

|

($31.0)

|

($46.0)

|

($41.6)

|

($231.2)

|

|

General Government

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Military

|

$7.4

|

$43.7

|

$2.8

|

$0.9

|

$9.3

|

$64.0

|

|

Food and Agriculture

|

—

|

—

|

2.0

|

5.7

|

49.9

|

57.6

|

|

Other

|

21.1

|

2.7

|

19.9

|

9.4

|

1.0

|

54.0

|

|

Subtotals

|

($28.4)

|

($46.4)

|

($24.7)

|

($15.9)

|

($60.2)

|

($175.6)

|

|

Health and Human Services

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

State Hospitals

|

$17.2

|

$16.4

|

$12.1

|

$68.2

|

$37.0

|

$151.0

|

|

Subtotals

|

($17.2)

|

($16.4)

|

($12.1)

|

($68.2)

|

($37.0)

|

($151.0)

|

|

Totals

|

$7,215.2

|

$31,201.3

|

$6,589.6

|

$5,861.3

|

$5,874.0

|

$56,741.5

|

The plan proposes to fund capital infrastructure from a variety of sources. Most of the plan—$32 billion, or 57 percent—is proposed to be from federal funds. Most of the remaining amount would be from various special funds ($12 billion)—almost all for transportation—and bond funds ($6 billion). Only $300 million would be funded directly from the General Fund.

In addition, for many state departments, the plan provides general descriptions of their existing facilities, the major drivers of infrastructure needs (such as program expansions or aging infrastructure), and proposals for new infrastructure. For example, for the California Highway Patrol (CHP), the plan identifies roughly 2 million square feet of state–owned and leased facilities, including over one hundred area offices. The plan describes the major drivers of CHP’s infrastructure needs as personnel growth, changes in evidence and records retention responsibilities and requirements, and the need to retrofit locker rooms to accommodate women. The plan proposes $398 million over the coming five years to work to address those needs through a statewide office replacement program.

Deferred Maintenance Proposal. In addition to capital outlay, the plan proposes $815 million from various fund sources to address statewide deferred maintenance needs that it estimates at about $65 billion (see Figure 3). Of this spending, $337 million is proposed to repay a General Fund loan from the Highway Users Tax Account, with the monies allocated for state highway pavement rehabilitation and maintenance, traffic management mobility, and local streets and roads projects. Additionally, the plan includes $188 million for the K–12 Schools Emergency Repair Program and $175 million for community colleges (to be split equally between maintenance projects and instructional support, such as replacement of library materials and classroom projectors). The Governor’s budget also includes a total of $100 million from the General Fund to help support the deferred maintenance needs of nine departments. Finally, the plan proposes $15 million from the State Court Facilities Construction Fund to address maintenance projects within the courts.

Figure 3

Administration’s Deferred Maintenance Proposal

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Department/Program

|

Amount of Proposed Funding

|

Amount of Identified Need

|

Percent of Identified Need Funded

|

|

Caltrans

|

$337

|

$59,000

|

0.6%

|

|

K–12 Schools Emergency Repair Program

|

188

|

—

|

—

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

175

|

—

|

—

|

|

Parks and Recreation

|

40

|

1,540

|

2.6

|

|

Corrections and Rehabilitation

|

20

|

959

|

2.1

|

|

Judicial Branch

|

15

|

2,000

|

0.8

|

|

Developmental Services

|

10

|

175

|

5.7

|

|

State Hospitals

|

10

|

69

|

14.5

|

|

General Services

|

7

|

105

|

6.7

|

|

State Special Schools

|

5

|

28

|

17.9

|

|

Military

|

3

|

86

|

3.5

|

|

Forestry and Fire Protection

|

3

|

27

|

11.1

|

|

Food and Agriculture

|

2

|

—

|

—

|

|

UC and CSU

|

—

|

573

|

—

|

|

Othera

|

—

|

45

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

$815

|

$64,607

|

1.3%

|

In this section, we describe some important policy issues raised by the administration’s 2014 infrastructure plan, as well as identify some areas where it does not provide key information. We then point out some possible ways to make the plan more helpful to the Legislature as it makes infrastructure decisions.

The plan serves an important role by raising some key policy issues for legislative consideration. In particular, the plan raises questions about (1) the appropriate roles of state versus local governments in funding some infrastructure, (2) whether the state is overly reliant on bond financing for infrastructure, and (3) how to address large backlogs of deferred maintenance in state facilities.

State Versus Local Responsibilities

A key consideration for the state is how much of its budget to devote to local infrastructure (for example, schools and parks) versus infrastructure with more substantial statewide implications (for example, University of California [UC] campuses, state courts, or state prisons). The Governor proposes to begin conversations on the responsibility of the state in paying for local infrastructure in two specific areas—school and community college facilities. Our office has noted the ability of school and community college districts to raise local revenue for their projects through local bonds, developer fees, facility improvement district levies, and parcel taxes. Moreover, Proposition 39 (enacted by voters in 2000) increased the ability of school and community college districts to help fund their infrastructure by reducing the vote requirement for local bond measures from two–thirds to 55 percent. (Since 2000, districts have been very successful in passing these local bond measures, with about 80 percent of all measures being approved by voters.) Assuming the state continues to share the cost of local projects with school and community college districts, we have recommended an alternative financing mechanism. Rather than using traditional state bonds, we have recommended providing districts with an annual per–pupil facilities grant that could be used for any allowable facilities purpose (see A New Blueprint for School Facility Finance, 2001).

We also note that legislative discussion of appropriate state versus local funding responsibilities is pertinent to other types of infrastructure (such as local streets and roads, jails, and parks). For example, in recent years, the line between state and local responsibility for funding and operating parks has become increasingly blurred as (1) the state has developed some parks that serve predominately local or regional needs, and (2) some local governments have entered into agreements to operate state parks. The Legislature may want to consider what the ongoing state role should be in funding infrastructure in these areas—examining such factors as the amount of statewide interest and responsibility in the area, the ability of local agencies to fulfill certain needs without state assistance, and the capacity of the state to fund these needs (versus funding its own infrastructure needs).

Reliance on Bond Funding

The plan also includes discussion of the state’s approach to funding infrastructure. Specifically, the plan notes that the state has increased its reliance on debt to fund capital projects, which has resulted in cost pressures to the state’s General Fund (the source of repayment for virtually all bonds). Accordingly, in the plan, the administration focuses on existing revenue streams—mostly federal funds, special funds, and already authorized bond funds—for its funding proposals. The plan does not propose the addition of any new taxes or new general obligation bonds.

The state’s funding approach for infrastructure projects is an important consideration for the Legislature. It must determine its preferred mix of debt and “pay–as–you–go” financing, recognizing that there is no one “right” approach. The use of borrowing for infrastructure projects is somewhat more expensive than paying for them up front because of the additional costs for interest. However, because most state facilities are intended to provide benefits over many years, it is reasonable that future as well as current taxpayers help fund them. Furthermore, given the volume of the state’s infrastructure needs and other competing priorities (including debt service on existing bonds), it is likely that bonds will continue to play a major role in infrastructure funding well into the future.

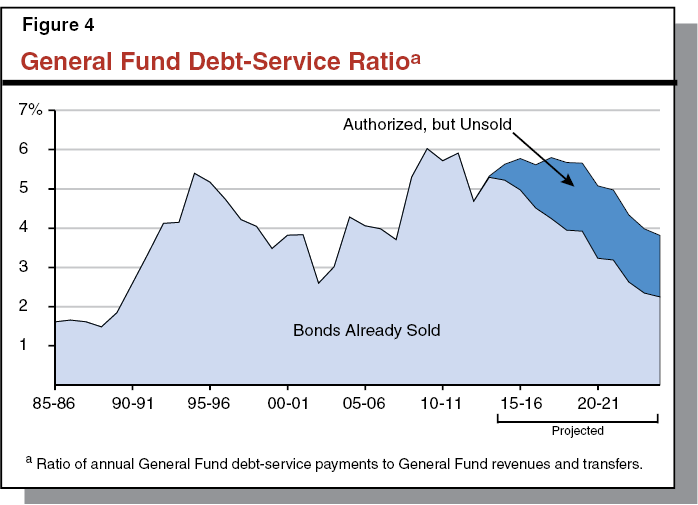

As the plan notes, to the extent that the state undertakes additional borrowing, it will affect the state’s debt–service ratio (DSR), which is the portion of the state’s annual General Fund revenues that must be set aside for debt–service payments and therefore are not available to support other state programs. The state’s DSR has changed over time, as shown in Figure 4. We believe that there is no one right level of DSR. The DSR simply provides an indication of the relative priority of debt service and infrastructure compared to other spending from the General Fund, with a higher DSR indicating an increased prioritization of spending on infrastructure financing relative to other programs. Thus, we think it is important for the Legislature to consider how much it is comfortable investing in infrastructure and relying on debt as a funding source given these trade–offs.

Focus on Deferred Maintenance

For the first time, the infrastructure plan includes information on deferred maintenance needs. This represents an important addition to the plan, as it acknowledges that the state’s infrastructure program should not only involve constructing new projects, but also maintaining existing ones to ensure that they can continue to serve the public into the future. Over the years, appropriate maintenance of infrastructure has been a chronic problem for the state. In times of fiscal stress—when the state is facing cuts to programs and services—maintenance funding is especially prone to being reduced or redirected to other priorities. However, deferred maintenance is problematic because when repairs to key building and infrastructure components are delayed, facilities can eventually require more expensive investments, such as emergency repairs (when systems break down), capital improvements (such as major rehabilitation), or replacement. As a result, while deferring annual maintenance avoids expenses in the short run, it often results in substantial costs in the long run.

While the Governor’s inclusion of deferred maintenance funding is commendable, the proposed funding would only address about 1 percent of the need identified in the infrastructure plan. The Legislature may want to ask the administration whether it has developed a strategy for addressing the remaining deferred maintenance backlog. In addition, the Legislature will want to ensure that the allocation of funds in the plan is consistent with legislative priorities. We note that some departments have a noticeably greater portion of their deferred maintenance needs funded in the plan than other departments. For example, the plan proposes to fund roughly 18 percent of the State Special Schools’ identified need, but only roughly 2 percent of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s (CDCR’s) identified need. Differing funding levels may make sense. However, it is unclear how the administration prioritized the distribution of funds across departments and whether, for example, the prioritization used reflects differences in severity of need. The Legislature may also want to consider whether there is alternative or additional funding for deferred maintenance from sources other than the General Fund (such as bond funds, private donations, or user fees). The Legislature could also provide guidance on the priorities for spending these deferred maintenance dollars within departments. While the highest priority projects might reasonably differ by department based on their different missions and types of facilities, the Legislature might want to have departments prioritize certain types of projects for 2014–15, such as those that address safety issues, reduce state liability, and prevent higher state costs in the future.

Finally, as the Legislature reviews the administration’s deferred maintenance proposal, it will want to consider its options for how to best ensure that departments are completing necessary routine and preventive maintenance on an ongoing basis. For example, departments could report what specific factors led to their deferred maintenance problems, including insufficient maintenance funding in the base budget or diversion of funds provided for maintenance to other areas of operations. Once the root causes were identified, the Legislature could consider policies to address them, such as by requiring departments to create plans to address their maintenance needs, set aside a certain amount of funding specifically for maintenance, and not redirect maintenance funding towards other priorities.

As we discuss below, the administration’s plan does not include some important information required under current state law. Specifically, the 2014 infrastructure plan does not include the list of infrastructure needs reported by departments, as well as certain details required for education programs.

Plan Does Not Include Infrastructure Needs Reported by Department

Current law requires that the annual infrastructure plan include the complete list of infrastructure needs identified by each state department. This requirement was adopted to allow the Legislature to understand the full scope of the state’s infrastructure demands and to make judgments about whether it agrees with the administration’s choices regarding which projects should receive funding.

However, the 2014 infrastructure plan only includes a list of projects proposed for funding, not the full list of needs identified by individual departments, which was included in prior infrastructure plans. We recognize that identifying the state’s infrastructure needs and separating them from “wants” is a difficult task. The administration indicates that omitting the full list is consistent with budget practices for departmental operating budgets. While this may be the case, existing statute specifically requires that the annual infrastructure plan include the identification of infrastructure requested by state departments. We believe that such information could help the Legislature as it evaluates infrastructure needs and funding choices.

Incomplete Information for K–12 Education

The plan is statutorily required to cover infrastructure needs, associated costs, and a funding proposal for schools (as well as the state higher education systems). This year’s plan does not identify school infrastructure needs. According to the administration, this is because of the challenges in quantifying those needs due to the variation in local school district needs. Despite the number of school facilities and the variation in their condition, past plans have made an attempt to address these issues. A more complete understanding of school facility conditions and differences in districts’ local revenue–raising capacity would help the Legislature determine how best to address these facilities moving forward. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature request the administration to include this information in future plans.

Incomplete Information for Higher Education

The plan also does not include the infrastructure needs or proposed funding for the UC system or, after 2014–15, for the California State University (CSU) system. The administration’s rationale for excluding this information is that capital funding is now incorporated into UC’s main appropriation rather than budgeted separately, and the administration proposes a similar approach for the CSU system. We have expressed several concerns with this funding approach. It removes project review and oversight from the regular budget process. This, in turn, makes weighing the relative benefits of higher education infrastructure versus other state infrastructure priorities even more difficult. It also merely shifts debt from the state as a whole to a segment of the state, without a guarantee that shifting the debt in this way will benefit either the state or the segments in the long run. We believe including the needs and funding for higher education in the infrastructure plan, consistent with statute, would be valuable.

The plan is an important tool for the Legislature as it considers infrastructure decisions. We recognize that it is not feasible or desirable for the plan to include all possible information on state–funded infrastructure. To do so would require too many resources and would produce a document that would be unwieldy. However, we think there are a few additional types of information that, while not currently required, would add significant value and should be considered for inclusion in future plans.

State Spending on Local Infrastructure Projects

The plan generally focuses on state infrastructure. However, the state provides substantial funds for local infrastructure in areas such as local streets and transit, resources and environmental protection, and K–12 public schools and community colleges. In the decade ending in 2010, more than half of the state’s infrastructure spending was administered by local agencies. Much of the state’s spending on local infrastructure is paid for through bonds. In the current year, for example, roughly half of the state’s general obligation bond debt–service payments are for K–12 public schools and community colleges.

The administration has proposals that involve local infrastructure spending. For instance, the Governor’s budget for 2014–15 proposes $500 million in lease–revenue bonds for local jail construction to help counties address the impact of the 2011 realignment of jails. This proposal is in addition to $1.7 billion in lease–revenue bonds that the Legislature has approved since 2007 to fund jail construction and modification. For comparison purposes, the Governor’s proposed $500 million for jail funding is greater than the $377 million in capital spending that the Governor proposes for CDCR over the coming five years. Despite the large amount of new funding proposed for county jails in 2014–15, it is not included in the infrastructure plan. Due to the scale of state spending on local infrastructure and its effects on the state’s debt–service obligations, it would be valuable if it were included in the plan.

Additional Detail on Significant Projects

In the five years covered by the plan, the Legislature is likely to face decisions on some emerging infrastructure issues that are high priorities for the administration. However, the plan does not include much detail on some of these issues, leaving substantial uncertainty regarding the specifics of how the administration intends to address them and how this will affect the state’s financial capacity for other projects. For example, one of the administration’s infrastructure priorities is water. In January 2014, the administration released a Water Action Plan, which is a five–year plan that addresses key water challenges facing the state. For example, the Water Action Plan calls for the implementation of the Bay Delta Conservation Plan (BDCP), which proposes water reliability and environmental restoration components estimated to cost about $25 billion. The infrastructure plan notes that funding for the BDCP is not included because it is “off–budget.” However, the draft BDCP estimates approximately $4 billion of this cost will come from state funds, including already authorized bonds, future bonds, and other state funds and thus will have to go through the Legislature’s appropriation process. Some of these state funds are expected to be needed within the next five years; yet, the infrastructure plan does not appear to include any of these costs. It would be helpful if the plan included these expected expenditures. Additionally, we note that the state has infrastructure responsibilities and obligations in other areas, such as for restoration of the Salton Sea, which are not included in the plan.

Additional Project Details

The plan could also be improved by the addition of some detail for each project listed. In particular, it could be helpful if the list of proposed projects in the plan included the current phase (such as design or construction). This information would be useful to have at a project level so that policymakers could more easily see how many new projects are envisioned in the plan. In addition, it would be useful to see how each project in the plan would be funded, particularly given the limited funding available. While this information may be available in individual capital outlay budget change proposals, it would be helpful for it to be consolidated in the annual infrastructure plan so that the Legislature could look at the totality of projects. Given the amount of detail this information would include, it might make sense for the administration to make it available in another easily accessible way (for example, through DOF’s website) rather than including such information in the actual infrastructure plan.

Given the importance of addressing infrastructure holistically and the challenges associated with doing so, it is important for the Legislature to engage on this issue. In the following section, we suggest some questions the Legislature may wish to consider as it does so. We also propose a possible institutional change—the establishment of infrastructure committees, which could promote more active and coordinated legislative involvement on this issue.

Questions for Legislative Consideration

Infrastructure is an issue that cuts across policy areas. It can be difficult to know how to best approach it given its scale and complexity. In order to help the Legislature as it attempts this challenging task, we suggest several broad questions the Legislature may find helpful in guiding its future discussions.

What Are the State’s Long–Term Policy and Infrastructure Goals? The Legislature will want to debate and define statewide policy goals and objectives and how they affect infrastructure. For instance, broad policy goals might include improving transportation access or mobility, ensuring water reliability, addressing environmental challenges, or improving access to educational opportunities. Within those goals, the Legislature might want to consider setting specific objectives—such as reducing hours of traffic delay or vehicle miles traveled, reducing carbon emissions, or achieving higher college completion rates. While the Legislature has already articulated goals in a variety of areas, it has not consolidated them or fully evaluated them in the context of how they will affect infrastructure decisions. For instance, the Legislature has expressed its commitment to achieving reductions in greenhouse gas emissions through the passage of AB 32 and other related legislation, which is likely to affect state infrastructure decisions around transportation and energy efficiency of state buildings, among other things. Statewide goals and objectives are important since they should drive choices regarding which infrastructure areas or large projects merit particular state focus.

How Should the State Prioritize Competing Infrastructure Needs? As it considers its policy and infrastructure goals, the Legislature will also wish to consider how specific infrastructure needs should be prioritized and weighed against each other. The state currently lacks such a methodology, making it difficult to establish the relative importance of projects across program areas. The Legislature may wish to articulate certain overarching priorities. For example, it may want to decide to give preference to projects or proposals that address broad state goals, reduce future state costs, protect health and safety, fulfill legal requirements, or leverage other funding streams.

Which Needs Should Be Addressed by the State? The Legislature will also want to consider which needs should be addressed by the state and which should be left to local agencies or private entities. As mentioned previously, given the large scale of the infrastructure needs across the state, it is important for the Legislature to think about the extent to which it can continue to sustain its historical role in funding infrastructure that meets predominately local needs.

How Can Policy Changes Reduce Demand for New Infrastructure? As it considers infrastructure investments, the state may want to explore policy changes that reduce demand for state–funded infrastructure. Such demand management policies include better utilization of existing facilities and higher user fees. For instance, higher education policies could place a greater emphasis on distance education and improved use of facilities during the summer. Similarly, transportation policies could promote more efficient use of the state’s existing highway system and potentially reduce the demand for limited funds to build new facilities such as by improving traffic flow and encouraging more efficient use of roadways.

What Funding Approaches Should the State Use? The Legislature may also want to consider the appropriate method for funding the state’s infrastructure projects and whether it agrees with the Governor’s cautious approach to taking on new General Fund commitments, including debt obligations. As mentioned previously, infrastructure spending, whether pay–as–you–go spending or debt–service payments, come at the expense of spending on other areas. Thus, infrastructure financing choices represent policy trade–offs that the Legislature will have to make. The Legislature may want to explore not only funding approaches, but also the feasibility of other funding sources besides the General Fund, such as special funds and user fees. For example, the Legislature has increased criminal and civil fines and fees to support new court facilities.

What Are Ongoing Costs Associated With Infrastructure Decisions? Finally, the Legislature will want to think about the ongoing costs associated with projects and proposals. Investments in new infrastructure typically result in ongoing increased operating costs for staffing, utilities, and maintenance of new facilities. For example, additional prison facilities require more correctional officers and inmate health care staff, and the acquisition of park land frequently requires additional park employees to operate and maintain facilities, trails, and roads for public use. On the other hand, some infrastructure investments can actually reduce costs by lowering facility operational costs or enhancing the efficiency of program delivery. For instance, building renovations or replacements can reduce energy use and ongoing maintenance needs, which can result in savings that can at least partially offset the capital costs.

Legislature May Want to Create Infrastructure Committees

As discussed previously, there are many key policy questions related to infrastructure that need to be addressed. The administration’s infrastructure plan provides a valuable starting point, but the usefulness of this and future infrastructure plans will largely be determined by how the Legislature decides to incorporate them into its policymaking processes.

We believe that, given the importance and complexity of these issues, it is critical that the Legislature consider how, as an institution, it addresses infrastructure issues. We have recommended in the past that the Legislature establish committees to deal with capital outlay issues. For example, the creation of a joint infrastructure policy committee would provide one such mechanism for the Legislature to make its decisions regarding capital priorities. These priorities could be reflected in resolutions outlining the Legislature’s key policies in assessing infrastructure proposals. The policy committee’s membership could include the chairs of relevant policy and budget committees (transportation, education, et cetera) to ensure policies adopted by the committee are applied throughout different program areas. Some important considerations and decisions for the policy committee could include:

- Assessing the state’s infrastructure data and creating legislation to improve data collection when necessary.

- Reviewing the administration’s infrastructure plan and monitoring the state’s progress in implementing the plan.

- Setting priorities for infrastructure spending across programs.

- Analyzing proposed bond acts to ensure they fit within priorities, plans, and funding capabilities.

- Determining which local or other non–state programs should receive funding.

- Developing institutional expertise in capital outlay topics such as financing, construction delivery methods, and cost escalation.

- Considering whether the Legislature would benefit from changes to future infrastructure plans and creating legislation to facilitate those changes when necessary.

There are many different ways the Legislature could respond to the annual infrastructure report and the related budgetary proposals of the administration—a joint infrastructure committee represents just one possible approach. What is critical, however, is that the Legislature independently engages with the administration on the issue of infrastructure and helps move the state to a less fragmented infrastructure planning and decision–making process.