Meeting California’s demands for water while protecting the environment presents several challenges. These include (1) needing to transport water and store it until it is needed; (2) providing adequate water to cities, farms, and the fish species during dry periods; (3) treating drinking water to safe levels and treating wastewater so it can be discharged back into the environment; and (4) mitigating the negative impacts of human water use on the environment. Such challenges can be intensified during droughts, such as the multiyear drought that began in California in 2011.

In order to address some of these challenges, in August 2014, the Legislature approved Chapter 188, Statutes of 2014 (AB 1471, Rendon), which placed before the voters a water bond measure primarily aimed at providing clean, safe, and reliable water supplies and restoring habitat. On November 4, 2014, voters approved the water bond measure—Proposition 1. In this report, we (1) provide background information on Proposition 1, (2) review the Governor’s proposals to implement the bond, (3) identify key implementation principles, and (4) recommend steps for the Legislature to ensure that the bond is implemented effectively—meaning that cost–effective projects are funded and that such projects are adequately overseen and evaluated.

California’s water system is complex. This complexity can be seen in how the system is structured—with multiple sources of water that are interconnected in various ways. It is also evident in how the system is financed—using a variety of sources at the local, state, and federal level to meet the needs of urban and agricultural water users and the environment.

Multiple Sources of Water in California. A majority of the state’s water comes from rivers, much of it from Northern California and from snow in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Water available underground (referred to as “groundwater”) makes up roughly one–third of the state’s water use and is more heavily relied on in dry years. A small share of the state’s water also comes from other sources, such as capturing rainwater, reusing wastewater (water recycling), and removing the salt from ocean water (desalination).

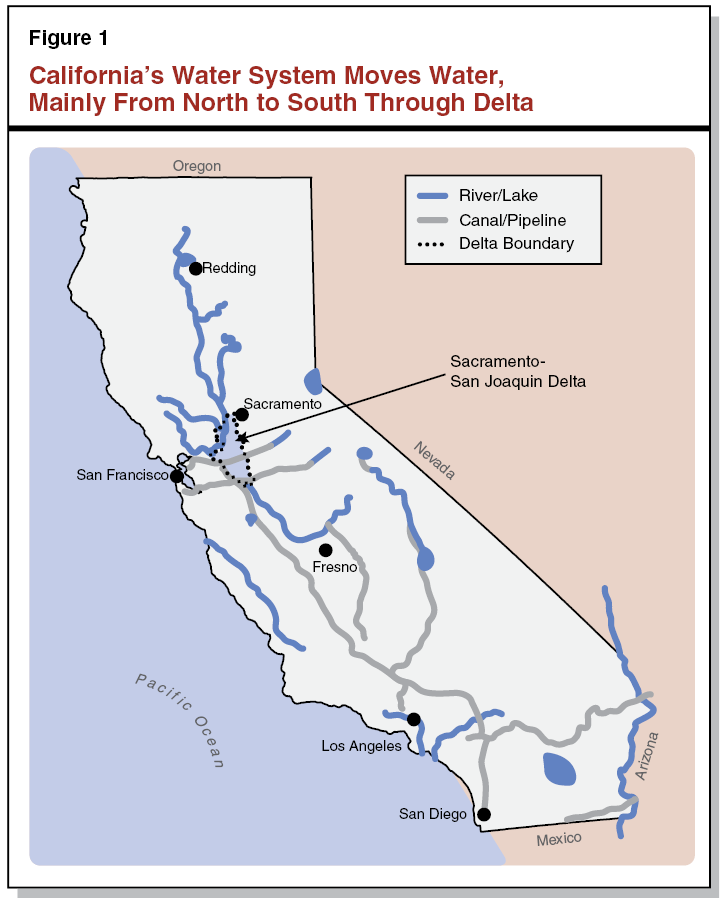

State’s Water System Is Interconnected in Many Ways. The various sources and uses of water are connected to one another in many ways—some direct and others more indirect. These interconnections mean that the supply and use of water in one part of the state can affect its availability in other parts of the state. First, water is often moved long distances to meet needs in parts of the state where less precipitation occurs. Specifically, the State Water Project and the federal Central Valley Project move water from rivers in Northern California through the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta (Delta), where it is pumped into over 400 miles of canals to the Central Valley and Southern California. Thus, demands south of the Delta can put pressure on sources of water in Northern California, and additional water usage in Northern California can leave less water available for use in other parts of the state. Figure 1 shows some of the major water sources, canals, and pipelines that move water in California.

Second, water is typically used multiple times before it is discharged into the ocean or groundwater. For example, a city will often divert water from a river at one point and treat it for various purposes (such as for drinking). After using the water, the city treats the water at a wastewater treatment plant and then returns it to the river. However, to the extent that upstream users return less water than they take from a water body, it leaves less water available for downstream users or the environment.

Third, groundwater and surface water are connected. In some places, groundwater is physically connected to water in a nearby river or water body. Moreover, groundwater is an important backstop when less surface water is available in dry years, such as during times of drought. Conversely, surface water can then be used to replenish groundwater supplies in wetter years.

Local Agencies Fund Most Water Programs. Local agencies (such as water districts, cities, and counties) provide water to urban and agricultural customers throughout the state. These local agencies account for most of the spending on water programs in the state—roughly $26 billion per year in recent years. About 80 percent of this spending is paid for by individuals (ratepayers) through their water bills. Local agencies also pay for projects using other sources, including state funds, federal funds, and local taxes. While most people get their water from these public water agencies, about one–sixth of Californians get their water from private water companies.

State Also Funds Water Programs. The state also plays an important role in funding various water programs and activities. Specifically, the state runs programs to (1) conserve, store, and transport water around the state; (2) protect water quality; (3) provide flood control; and (4) protect fish and wildlife habitat. The state provides support for these programs through direct spending, as well as grants and loans to local governments, nonprofit organizations, and investor owned water companies. (The federal government runs similar programs.) In recent years, the state has relied heavily on general obligation bonds to fund these water–related programs.

The passage of Proposition 1 continues the use of bond funds as the primary source of state funding for water–related programs. Specifically, the proposition provides a total of $7.5 billion in general obligation bonds for various programs. (Of this total, $425 million is redirected from unsold bonds that voters previously approved for water and other environmental purposes.) Below, we describe the major provisions of Proposition 1.

The bond measure provides funding for the following categories:

- Water Storage ($2.7 Billion). The bond includes $2.7 billion for new water storage projects, which could include dams and projects that replenish groundwater. Proposition 1 specifies that these funds are available only to support the following public benefits associated with storage: (1) ecosystem improvements; (2) water quality improvements; (3) flood protection; (4) emergency response, including emergency water supplies; and (5) recreation.

- Watershed Protection and Restoration ($1.5 Billion). The bond provides $1.5 billion for various projects intended to protect and restore watersheds and other habitat throughout the state. This funding could be used to restore bodies of water that support native, threatened, or endangered species of fish and wildlife; purchase land for watershed conservation purposes; reduce the risk of wildfires in watersheds; and purchase water to support wildlife. These funds include: (1) $475 million to pay for certain state commitments to fund environmental restorations; (2) $373 million for restoration projects throughout the state (including $88 million specifically for the Delta); (3) $328 million for ten state conservancies and the Ocean Protection Council, which are displayed in Figure 2; (4) $200 million to increase the amount of water flowing in rivers and streams (such as by buying water); (5) $100 million for an urban creek (the Los Angeles River); and (6) $20 million for urban watersheds.

- Groundwater Sustainability ($900 Million). The bond provides $900 million for grants and loans to promote groundwater sustainability, including $100 million specifically for grants for projects that develop and implement groundwater plans and projects.

- Regional Water Management ($810 Million). The bond provides $810 million for regional projects that are included in specific plans developed by local communities. These projects are intended to improve water supplies, as well as provide other benefits, such as habitat for fish and flood protection. The amount provided includes $510 million for allocations to specific regions throughout the state through the Integrated Regional Water Management (IRWM) program, $200 million for projects and plans to manage runoff from storms in urban areas, and $100 million for water conservation projects and programs.

- Water Recycling and Desalination ($725 Million). The bond includes $725 million for projects that treat wastewater or saltwater so that it can be used later. For example, the funds could be used to test new treatment technology, build a desalination plant, and install pipes to deliver recycled water.

- Drinking Water Quality ($520 Million). The bond includes $520 million to improve access to clean drinking water for disadvantaged communities ($260 million) and help small communities pay for wastewater treatment ($260 million).

- Flood Protection ($395 Million). The bond provides $395 million for projects that both protect the state from floods and improve fish and wildlife habitat, including $295 million to improve levees or respond to flood emergencies specifically in the Delta and $100 million for flood control projects anywhere in the state.

Proposition 1 contains provisions that specify, to varying degrees, how the bond funds are to be spent. These provisions affect how the funds will be allocated, including which projects can be selected and which entities are eligible to receive funding.

Departments Responsible for Bond Implementation. At least 16 state departments are responsible for administering portions of Proposition 1. These departments include the Department of Water Resources (DWR), the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB), the Department of Fish and Wildlife (DFW), the California Water Commission, and various conservancies.

Appropriations. Proposition 1 provides a continuous appropriation to the California Water Commission for the $2.7 billion for water storage. This means the commission would not have to go through the state budget process to spend these funds. For all other funding provided in the proposition, the Legislature generally would allocate money annually to state departments in the state budget process.

Process for Selecting Projects. Projects funded under Proposition 1 would generally be selected on a competitive basis. The measure specifies a process for administering departments to follow when developing guidelines for competitive grants. For example, Proposition 1 requires that such guidelines include monitoring and reporting requirements and be posted on the website of the California Natural Resources Agency (CNRA). Administering departments must hold three public meetings before finalizing their grant guidelines. Upon adoption, copies of the guidelines must be sent to the Legislature. In some cases—such as projects implemented directly by state departments—a competitive grant process is not required.

Types of Projects Eligible for Bond Funds. The measure provides direction on the types of projects that are eligible for bond funding. In many cases, the eligible uses are broad enough to encompass a wide variety of projects. For instance, the funding for watershed protection and restoration can go to a broad range of projects as long as they provide multiple benefits (such as improved water quality and habitat health) consistent with statewide priorities. Under the measure, the Legislature can provide state departments with additional direction on what types of projects or programs could be chosen (whether through a competitive or other process) through statute. However, the measure states that the Legislature cannot allocate funding to specific projects. Instead, state departments will choose the projects. In addition, the measure specifically prohibits funding a canal or tunnel to move water around the Delta.

Requirements for Matching Funds. The $5.7 billion provided in the proposition for water storage, groundwater sustainability, regional water management, water recycling, and water quality projects is available only if recipients provide matching funding to support the projects. The required share of matching funds is generally at least 50 percent of the total cost of the project, although this can be waived or reduced in some cases, such as when projects serve disadvantaged communities (communities where median household income is at least 20 percent below the rest of the state). The remaining bond allocations do not require matching funds.

Proposition 1 also includes provisions that affect how projects would be administered and overseen. For example, the measure specifies that up to 5 percent of the bond allocations can be used for administrative costs and up to 10 percent can be used for planning and monitoring efforts. In addition, the measure requires the Department of Finance (DOF) to audit the expenditure of grant funds and allows for additional auditing in the event that DOF identifies issues of concern. Proposition 1 also requires that CNRA annually publish a list of all program and project expenditures on its website.

Governor’s 2015–16 Budget Proposals

The Governor’s budget proposes to appropriate $533 million in 2015–16 to begin implementing the $7.5 billion available in Proposition 1. The administration has also released a multiyear expenditure plan for the bond proceeds, as shown in Figure 3. In some cases, departments are requesting that the out–year expenditures after 2015–16 be included in their base budgets. In other cases, departments would submit future budget proposals to the Legislature requesting these funds, perhaps reflecting modifications from their current plans.

Figure 3

Governor’s Multiyear Funding Plan for Proposition 1 Bond Funds

(In Millions)

|

Purpose

|

Bond

Allocation

|

2015–16

|

2016–17

|

2017–18

|

2018–19

|

2019–20

|

After 2019–20

|

|

Water storage

|

$2,700

|

$3

|

$4

|

$418

|

$411

|

$391

|

$1,417

|

|

Watershed protection and restoration

|

1,495

|

178

|

203

|

206

|

170

|

433

|

273

|

|

Groundwater sustainability

|

900

|

22

|

104

|

159

|

206

|

206

|

186

|

|

Regional water management

|

810

|

57

|

180

|

239

|

117

|

190

|

11

|

|

Water recycling and desalination

|

725

|

137

|

221

|

177

|

135

|

27

|

15

|

|

Drinking water quality

|

520

|

136

|

113

|

113

|

88

|

50

|

10

|

|

Flood protection

|

395

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

387

|

|

Administration and oversighta

|

—

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

$7,545

|

$533

|

$825

|

$1,313

|

$1,126

|

$1,297

|

$2,298

|

Figure 4 summarizes the specific funding levels by category proposed by the Governor. Generally, after the Legislature appropriates the bond funds, departments would have three years to encumber (or commit) funds for capital projects and two additional years to spend them. This provides a total of five years from the budget appropriation for departments to spend the funds. Below, we summarize the administration’s Proposition 1 proposals for 2015–16.

Figure 4

Proposition 1 Bond Funds—Governor’s 2015–16 Proposals

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Purpose

|

ImplementingDepartments

|

Bond

Allocation

|

Proposed in 2015–16

|

|

Amount

|

Percent of Total Allocation

|

|

Water Storage

|

|

$2,700

|

$3

|

—

|

|

Water storage projects

|

CWCa

|

2,700

|

3

|

—

|

|

Watershed Protection and Restoration

|

|

$1,495

|

$178

|

12%

|

|

Various state obligations and agreements

|

CNRA

|

475

|

—

|

—

|

|

Watershed restoration benefiting state and Delta

|

DFW

|

373

|

37

|

10

|

|

Conservancy restoration projects

|

Conservancies

|

328

|

84

|

25

|

|

Enhanced stream flows

|

WCB

|

200

|

39

|

19

|

|

Los Angeles River restoration

|

Conservancies

|

100

|

19

|

19

|

|

Urban watersheds

|

CNRA

|

20

|

<1

|

1

|

|

Groundwater Sustainability

|

|

$900

|

$22

|

2%

|

|

Groundwater cleanup projects

|

SWRCB

|

800

|

1

|

—

|

|

Groundwater sustainability plans and projects

|

DWR

|

100

|

22

|

22

|

|

Regional Water Management

|

|

$810

|

$57

|

7%

|

|

Integrated Regional Water Management

|

DWR

|

510

|

33

|

6

|

|

Stormwater management

|

SWRCB

|

200

|

1

|

—

|

|

Water use efficiency

|

DWR

|

100

|

23

|

23

|

|

Water Recycling and Desalination

|

|

$725

|

$137

|

19%

|

|

Water recycling and desalination

|

DWR and SWRCB

|

725

|

137

|

19

|

|

Drinking Water Quality

|

|

$520

|

$136

|

26%

|

|

Drinking water for disadvantaged communities

|

SWRCB

|

260

|

69

|

27

|

|

Wastewater treatment in small communities

|

SWRCB

|

260

|

66

|

26

|

|

Flood Protection

|

|

$395

|

—

|

—

|

|

Delta flood protection

|

DWR and CVFPB

|

295

|

—

|

—

|

|

Statewide flood protection

|

DWR and CVFPB

|

100

|

—

|

—

|

|

Administration and Oversight

|

|

—

|

$1

|

N/A

|

|

Administrationb

|

DWR and CNRA

|

—

|

1

|

N/A

|

|

Totals

|

|

$7,545

|

$533

|

7%

|

Water Storage ($3 Million). The Governor proposes $3 million and 12.3 positions (4.3 redirected) for DWR to provide administrative support to the California Water Commission for its water storage program. These positions would be supported by the continuously appropriated water storage funds.

Watershed Protection and Restoration ($178 Million). The Governor’s budget includes a total of $178 million for various watershed protection and restoration projects. This amount includes funding for:

- Projects Benefiting State and Delta. The budget provides $37 million and 41.5 positions (37 redirected) to DFW for competitive grants to implement habitat restoration projects statewide and within the Delta. Potential projects include restoring coastal wetland habitat, purchasing conservation easements to create strips of habitat along rivers, and installing or improving fish screens on water intakes. The DFW plans to issue annual solicitations for the next ten years to fully expend the allocations in the bond set aside for this purpose.

- Conservancy Restoration Projects. The budget includes $84 million and 13 positions for ten state conservancies and for the Ocean Protection Council to conduct restoration and habitat conservation work. Potential projects include the acquisition and restoration of tidal wetlands, implementation of the Lake Tahoe Environmental Improvement Program, and completion of components of the San Joaquin River restoration. The amount of funding proposed for each conservancy is shown in Figure 5.

- Enhanced Stream Flows. The budget provides $39 million and 4.5 positions (2 limited–term) for the Wildlife Conservation Board (WCB) to implement a program aimed at increasing stream flow. Activities could include purchasing long–term water transfers (at least 20 years) to reserve them for instream flows, implementing irrigation efficiency improvements that allow additional water to be left instream, and wetland restoration projects.

- Urban Creek—Los Angeles River Restoration. The budget includes $19 million for the San Gabriel and Santa Monica Mountains Conservancies to implement restoration projects along the Los Angeles River and its tributaries.

- Urban Watershed Restoration. The budget includes $125,000 and one position for CNRA to administer a grant program for restoring unspecified urban watersheds.

Figure 5

Proposition 1 Proposals for Conservancy Restoration Projects

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

BondAllocation

|

Proposed in 2015–16

|

|

Amount

|

Percent of Total

|

|

State Coastal Conservancy

|

$101

|

$15

|

15%

|

|

Delta Conservancy

|

50

|

10

|

20

|

|

Ocean Protection Council

|

30

|

10

|

32

|

|

San Gabriel Conservancy

|

30

|

10

|

34

|

|

Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy

|

30

|

4

|

14

|

|

Sierra Nevada Conservancy

|

25

|

10

|

41

|

|

San Diego River Conservancy

|

17

|

3

|

18

|

|

California Tahoe Conservancy

|

15

|

14

|

94

|

|

Baldwin Hills Conservancy

|

10

|

2

|

21

|

|

Coachella Valley Mountains Conservancy

|

10

|

3

|

25

|

|

San Joaquin River Conservancy

|

10

|

3

|

28

|

|

Totals

|

$328

|

$84

|

26%

|

Groundwater Sustainability ($22 Million). The budget proposes $22 million and 5.5 positions (all redirected) for DWR to fund the development of local groundwater sustainability plans and the installation of groundwater monitoring wells. The budget also includes $600,000 and 5.5 positions for SWRCB to begin developing its groundwater cleanup program.

Regional Water Management ($57 Million). The Governor’s budget proposes $57 million for regional water management projects. This amount includes funding for:

- IRWM. The budget provides $33 million and 9.1 positions (6.1 redirected) to DWR for the IRWM program, including grants for IRWM planning and grants aimed at increasing involvement of disadvantaged communities in these regional efforts.

- Stormwater Management. The budget proposes $600,000 and 4.5 positions for the SWRCB to begin developing a stormwater grant program.

- Water Use Efficiency. The budget provides $23 million to DWR for water use efficiency projects. This includes (1) $12.6 million and 5 positions (3 redirected) for agricultural water use efficiency projects and programs (such as providing technical assistance on implementing irrigation efficiency measures, researching crop water use, and outreach to farmers on data sources that can improve agricultural operations) and (2) $10.6 million and 4 positions (1 redirected) for urban water use efficiency projects and programs (such as efforts to increase public awareness regarding the value of water conservation, provide technical assistance on water rates structures and leak detection, and reduce outdoor water use).

Water Recycling and Desalination ($137 Million). The Governor’s budget provides $137 million for water recycling and desalination projects. This amount includes funding for:

- Water Recycling. The budget proposes $132 million and 7 positions for SWRCB’s existing water recycling grant program. Potential projects include feasibility studies, demonstration projects, and larger scale water recycling projects. (We note that the Governor’s budget includes an additional 27 administrative and information technology positions for SWRCB to support all of its proposed programs.)

- Desalination. The budget proposes $6 million and 2 positions for DWR to fund the development of desalination projects.

Drinking Water Quality ($136 Million). The budget proposes $136 million for SWRCB to improve drinking water quality. This amount includes funding for:

- Drinking Water for Disadvantaged Communities. The budget includes $69 million and 7 positions to fund drinking water financial assistance, which is an existing SWRCB program. This program provides grants and low–interest loans to fund construction of drinking water projects, such as water treatment plants and new wells.

- Wastewater Treatment in Small Communities. The budget includes $66 million and 3 positions to fund grants and low–interest loans for construction of wastewater treatment projects. This can include projects to construct new wastewater treatment plants or connect a community to an existing plant nearby. The SWRCB will use this funding to expand its existing Small Community Wastewater Program.

Administration and Oversight ($1 Million). The budget proposes $189,000 and 1 position to CNRA for bond administration activities, such as reviewing grant program guidelines, managing cash resources for bond programs, and reporting information on bond expenditure and encumbrances. In addition, the budget proposes $627,000 and 5 positions (1 redirected) for DWR to support various administrative activities related to Proposition 1.

In order to assist the Legislature regarding the implementation of Proposition 1, including its deliberations on the Governor’s budget proposals for 2015–16, we developed three guiding principles. As shown Figure 6, these principles are (1) furthering state priorities, (2) funding cost–effective projects for the state, and (3) ensuring accountability and oversight. These principles can inform how money is allocated to projects, promote transparency, and ensure better outcomes. We recognize that there are trade–offs inherent in implementing a bond measure based on these principles. For example, conducting benefit–cost analyses for every project that is proposed for funding could help identify those projects that are most cost–effective. However, such a process would be very costly and ultimately impractical. Below, we discuss each of our three principles in more detail.

Figure 6

LAO Principles for Implementing Proposition 1

- Furthering State Priorities. The state should make sure that programs are implemented in ways that further its priorities, specifically those laid out in Proposition 1 and other statutes. This will ensure that expenditures are consistent with other state activities.

|

- Funding Cost–Effective Projects for the State. State funds should be used to support state–level public benefits. Projects should generate more benefits than would otherwise occur and provide benefits over a long period of time.

|

- Ensuring Accountability and Oversight. Departments should collect and evaluate data on project outcomes to better allow the Legislature and voters to understand what has been achieved with the investment of the bond dollars.

|

An important consideration when spending bond funds is how the expenditure of the funds will further the state’s priorities, specifically those laid out in the bond act as well as in other statutes. Making sure that bond funds further state priorities will ensure that expenditures are consistent with the state’s other activities and will not result in negative impacts on other state goals.

Proposition 1 Lists Priorities for Spending Bond Funds. Proposition 1 includes numerous priorities that reflect the proposition’s intended goals. Figure 7 lists selected priorities and requirements from the bond. As noted in the figure, some of the specified priorities apply to all funding allocations in the bond, such as those listed in the measure’s findings and general provisions. For example, the general provisions require that the funds result in public benefits addressing the state’s most critical priorities for public funding. The general provisions also state that special consideration should be given to projects that employ new or innovative technology or practices.

Figure 7

Examples of Priorities and Requirements in Proposition 1

|

Applies to All Allocations

|

- Fund high priority public benefits.

- Prioritize projects that leverage other funds or produce the greatest public benefit.

- Prioritize projects that employ new or innovative technology or practices.

- Implement the California Water Action Plan.

- Have professionals in relevant fields review proposals.

|

|

Applies to Specific Allocations

|

- Implement water storage projects that provide measurable improvements to the Delta and its tributaries.

- Do not fund watershed protection activities already required by environmental regulations.

- Do not fund groundwater cleanup where there is a responsible party that could pay.

- Provide public benefits by improving groundwater storage and groundwater quality.

- Provide incentives for water agencies to collaborate on regional water management.

- Prioritize water recycling and desalination projects based on benefits such as increased water supply and water quality.

- Address the critical and immediate water treatment needs of disadvantaged, rural, or small communities.

- Implement flood protection projects that provide public safety and environmental benefits.

|

The bond also states that funds should be used to implement the objectives of the Governor’s Water Action Plan, which was released in January 2014. This plan identifies a series of actions that the administration believes the state should take over the subsequent five years to address a range of water–related challenges, such as reduced water supply and poor water quality. At the time of this report, the administration stated that it intends to release a report in early 2015 identifying a strategy to implement the Water Action Plan, including a schedule of activities, the estimated costs of those activities, and the expected funding source. Many of these activities will likely be funded with Proposition 1 funds.

As shown in Figure 7, Proposition 1 also provides specific goals or direction for certain funding allocations. For instance, the measure states that funds provided for watershed protection should be used to accomplish such purposes as to protect and restore aquatic, wetland, and migratory bird ecosystems, and that these improvements exceed what is required by existing environmental regulations.

Recent Legislation Describes Additional State Priorities. Several statutes enacted by the Legislature in recent years also lay out priorities and goals for the state’s policy on water and the environment. For example, a package of legislation passed in 2009 established state goals for improving water supply reliability and restoring the ecosystem of the Delta and set a statewide target for a reduction in water use. In addition, Chapter 524, Statutes of 2012 (AB 685, Eng), established a state policy that all people have the right to safe, clean, affordable, and accessible water. Although some pieces of legislation primarily address environmental issues outside of water, they can inform how the state spends Proposition 1 funds. For example, Chapter 488, Statutes of 2006 (AB 32, Núñez/Pavley), requires a reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Because California’s water delivery and treatment systems are highly energy intensive, increasing water use efficiency can reduce energy use and associated GHG emissions.

Funding Cost–Effective Projects for the State

Another important principle when implementing Proposition 1 will be to ensure that the state uses public funds to support projects that provide the greatest amount of public benefits to the state. Below, we define both private and public benefits, including “state–level” public benefits, and identify steps to help ensure that the state maximizes such benefits from the expenditure of Proposition 1 dollars.

Defining Private and Public Benefits. Most activities in the economy result in private benefits paid for by private entities, such as the purchase of goods and services. Private benefits can also include activities required to meet legal obligations, such as regulatory requirements. This is because meeting these requirements enables entities to perform other activities (such as building a desired project) that provide a direct private benefit to the regulated entity.

However, as discussed earlier, Proposition 1 intends that the investment of public funds result in the greatest public benefit. A public benefit is generally thought of as something that does not have clear private beneficiaries, or where it is too difficult to identify and charge the direct beneficiaries for the good or service. For example, protecting habitat for fish and wildlife generally provides public benefits because it is not feasible to allocate the costs of that activity to direct beneficiaries.

A given activity rarely results in only private or public benefits. This is because many programs and projects provide both private and public benefits simultaneously. For example, a given water storage project provides private benefits to the people receiving the water and also provides public benefits because it reduces flood risk for a downstream city. In addition, the extent to which an activity has public or private benefits depends on the specific circumstances. For example, when a dam releases water, that activity may have private benefits at some times (such as when the water is needed to meet regulatory requirements), but public benefits at other times (such as when the water released is above and beyond regulatory requirements to provide additional benefits for fish species).

Funding State–Level Public Benefits. In our view, state funds should only be used to support those activities that provide state–level public benefits. State–level public benefits provide value to the people of California as a whole, rather than specific local or regional communities, and thus should be paid for by the state. For example, it is more appropriate for the state to fund restoration at sites of statewide interest (such as Lake Tahoe) than a local park. In many cases, the same activity can have both state–level and local– or federal–public benefits. For example, restoring habitat to protect fish species that are legally protected by both the state and federal governments would provide both state– and federal–level public benefits. In such cases, state funds should only be used for the portion of the project that provides the state–level benefit, and other levels of government should provide funds for the portion of projects that benefit them directly. We note that the bond prioritizes projects that leverage non–state funding sources, such as local and federal funds.

Generating More Benefits Than Would Otherwise Occur. An important consideration when spending Proposition 1 funds is ensuring that the benefits of the funded projects are “additional.” This means that the projects provide benefits above what would have been achieved in the absence of state spending and that such benefits would not be provided by private parties or other levels of government. For example, if a water district already has plans to evaluate its pipes for leaks to reduce their water loss, the state should not use its limited funds to support that activity.

Limiting Bond Funds to Projects With Long–Term Benefits. As a general principle, general obligation bonds should be used for the construction and acquisition of capital improvements as well as associated planning costs. Directing bond funds on long–term capital improvements ensures that bond spending provides benefits over many years. It also ensures that funded projects have a lifespan that is consistent with the repayment schedule for the bonds that fund them, so that future taxpayers do not bear the cost of projects that do not benefit them. Generally, projects that provide shorter–term benefits or that are small–scale and routine in nature are more appropriately funded through ongoing, pay–as–you–go funding sources rather than long–term bonds.

Limiting Administrative Costs. Each dollar spent on administrative costs within a bond program is one less dollar that is available for infrastructure projects. Thus, the state should work to ensure that administrative costs are contained to the greatest extent possible and that bond funds do not end up funding the costs of an agency’s day–to–day program operations. Nevertheless, some level of administrative costs—including costs to plan and monitor projects—are necessary to ensure that the most cost–effective projects are selected for bond funding and that there is appropriate oversight over projects once they are funded.

Considering Trade–Offs Among Cost–Effectiveness and Other Priorities. While cost–effectiveness is an important priority, in some cases it may not be entirely consistent with other key legislative priorities. In such cases, these different priorities will need to be weighed against one another. For example, the state has historically made exceptions to the principle that the state should not fund private benefits in order to address concerns about some communities’ ability to pay for certain projects (such as the infrastructure to supply and treat drinking water). As previously indicated, Proposition 1 declares that every Californian should have access to clean, safe, and reliable drinking water. Accordingly, it is appropriate to fund some projects in communities that lack the ability to pay for these types of projects even if they are not the most cost–effective projects.

Additionally, there can be trade–offs between getting bond funds out quickly and planning and soliciting the most cost–effective projects. This is particularly likely to occur when departments are tasked with developing effective guidelines and soliciting proposals for new programs that they have not previously implemented. For example, SWRCB indicates that it did not request significant funding for groundwater cleanup as part of the Governor’s budget because it needed additional time to consider how to best administer the new program.

Another important principle when implementing Proposition 1 will be to ensure accountability for the expenditure of bond funds, in order to promote transparency and good outcomes. Taking steps to promote accountability will better allow the Legislature and voters to understand what has been achieved with the investment of the bond dollars.

Defining and Valuing Accountability. The Legislature will want to hold departments administering the bond accountable for their activities and outcomes. A key way of achieving this is through oversight and evaluation. Such oversight and evaluation can lead to better outcomes for several reasons. First, entities tend to focus resources in areas that they will be required to measure and evaluate. Thus, by adding additional focus to measuring and reporting information on bond activities and results, it can encourage grantees and departments to achieve as much as possible with the bond funds they are allocated. Second, providing the Legislature and public with information about what is achieved with bond funds will help them understand the benefits provided by the funds. This will allow them to hold departments receiving funding under the bond accountable for the implementation of their programs and projects. Third, evaluation of project outcomes can help inform subsequent decisions on how best to implement later rounds of funding through this bond. This information can also help shape potential future bonds or state programs by identifying lessons learned, as well as the programs and practices that were (and were not) successful at achieving desired outcomes.

Data Requirements for Accountability. In order to conduct the oversight and evaluation necessary for accountability, there must be sufficient and timely data. This data should not only provide information on the activities funded by bond dollars, but should also allow for measurement and evaluation of the outcomes that have been achieved with those funds (such as the volume of water that was recycled or the number of fish that were supported by restored habitat). For it to be useful, the data must be readily accessible to the Legislature, researchers, and the public and must be comparable across projects, programs, and departments. Making this data readily accessible also facilitates program evaluation by third parties like universities, which can provide valuable independent assessments of projects and programs.

In this section, we provide a series of recommendations to implement the principles described above by applying them to the allocations in the bond and to the specific proposals in the Governor’s 2015–16 budget. These recommendations are designed to better ensure that the most cost–effective projects are selected for funding and that sufficient oversight and evaluation is provided to ensure accountability for the funds spent. In our view, these recommendations build on the existing directions provided in the bond and represent a balance between adherence to the implementation principles and practical constraints. Figure 8 summarizes our recommendations.

Figure 8

LAO Recommendations to Promote Effective Bond Implementation

- Promote Cost–Effective Project Selection

- Ensure funding targeted to state–level public benefits.

- Require robust cost–effectiveness criteria for project selection.

- Consult with technical experts when needed.

- Limit operational and administrative costs.

- Require departments to submit staffing plans for all bond–related activities.

- Require granting departments to demonstrate link between budget requests and bond priorities.

|

- Oversight and Evaluation During Project Implementation

- Ensure data collection to support program evaluation.

- Facilitate oversight of projects, programs, and outcomes.

|

Governor’s Proposals Generally Consistent With Intent of Bond. Based on our analysis, we find that the Governor’s proposals generally align with the priorities described in Proposition 1 and in other recent legislation. The proposals also provide for some accountability measures. However, we note that, in many cases, departments are still in the process of developing grant program guidelines. These grant guidelines will identify the specific selection criteria, measures of success for projects, and reporting and other requirements for grantees. As such, these grant guidelines will play a critical role in ensuring that the most effective projects are chosen and that funded projects are adequately monitored to ensure they meet their desired outcomes.

We also note that various implementing departments indicated that they plan to conduct some of the activities we recommend below. In fact, according to some departments, they have conducted these activities in the past when implementing similar programs. In some instances, we still recommend that the Legislature require these activities because it is important to institutionalize such requirements in order to ensure that they stay in effect even when administrative leadership and personnel change.

Promote Cost–Effective Project Selection

Below, we make several recommendations to improve the cost–effectiveness of the projects that are ultimately selected to receive funds from Proposition 1.

As discussed above, a given activity may have public and private benefits, and whether something provides a benefit that is public or private might depend on how the project is implemented. We recommend the Legislature take actions that will ensure that bond funding targets state–level public benefits.

Clarify Definition for Certain State–Level Public Benefits. In many cases, departments will be choosing among projects that have both public and private benefits. In these cases, departments should choose projects with the greatest net benefits (including both private and public benefits). However, as noted above, state funds should only support the portion of the project that provides state–level public benefits. Some departments, however, have indicated that they would consider using bond funds to support certain categories of benefits that are often private. To address this issue, we recommend the Legislature pass budget trailer legislation defining public benefits for the following categories of benefits:

- Water Supply Benefits. Many departments intend to include certain water supply benefits—such as increased water supply and avoided water supply disruptions—in their criteria for selecting projects. However, these benefits are often private because the benefits accrue to a water system’s defined customer base. Therefore, we recommend the Legislature specify that water supply benefits are only public benefits to the extent that there is no identified group of beneficiaries (such as ratepayers) and that only these public water supply benefits are eligible for bond funding. The Legislature could exempt projects that serve disadvantaged communities from this requirement.

- GHG Reductions. Some departments, including SWRCB and DWR, intend to count GHG reductions from Proposition 1 projects as public benefits. For example, a water–recycling project could result in lower use of other energy–intensive water sources which could reduce GHG emissions. However, under AB 32, GHG emissions from many sectors of the economy are already limited (or capped) under the state’s cap–and–trade regulations. Therefore, emission reductions in the capped sector likely would have happened without bond funding and would not provide additional state–level public benefits. As such, we recommend that the Legislature specify that GHG reductions are public benefits only if they accrue to entities outside of the capped sector.

Limit Funds for Developing Groundwater Plans to Disadvantaged Communities. The Governor’s groundwater sustainability proposal would provide funding for communities to develop sustainable groundwater management plans. However, such plans are already required under the state’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act of 2014. Thus, we recommend the Legislature specify that funds for developing groundwater management plans only be available to disadvantaged communities, in order to address ability to pay concerns. This is because, as noted above, funding activities that benefit disadvantaged communities can meet important state priorities even when they do not provide clear state–level public benefits.

Ensure Water Storage Funding Supports Public Benefits. As noted above, Proposition 1 identifies five categories of benefits associated with water storage that may be counted as public, including ecosystem and water quality improvements. In its draft guidelines for quantifying benefits, the California Water Commission proposes to designate all benefits that fall into those categories as public benefits eligible for bond funds. However, it is possible that some of these benefits may not always be state–level public benefits. For example, a water storage project could result in a local (rather than state) public benefit if the project reduces flood risk for a specific city downstream. When the California Water Commission makes the guidelines and regulations for the program available for public comment, we recommend that the commission report to the Legislature on how it will determine which benefits are state–level public benefits. The Legislature could hold hearings if it determines that the California Water Commission’s approach is not consistent with legislative intent.

Ensure Water Recycling Funding Not Used To Meet Regulatory Requirements. Water recycling projects often include components that (1) treat water to very high levels of quality and (2) transport that water to an area where it can be injected into groundwater for long–term storage. State water quality regulations already require some communities to treat their wastewater to very high levels prior to it being discharged. Some grantees may request funding for water recycling projects in these areas. In such cases, the costs of the high–level treatment portion of a water recycling project should be borne by private beneficiaries. Since such treatment is required by regulation, it should not be supported with Proposition 1 funds. However, other water recycling projects (such as infrastructure needed to recharge groundwater) might provide a public benefit if it reduces water diversions and leaves more water available for the environment. We recommend that the Legislature prohibit the use of Proposition 1 funds for the costs of water recycling projects that are associated with treatment that is already required by regulation, while allowing the use of funds for other project costs that provide state–level public benefits.

Require Robust Cost–Effectiveness Criteria for Project Selection

As noted above, many departments intend to consider cost–effectiveness when selecting projects to support with Proposition 1 funds. In many cases, evaluating cost–effectiveness can be challenging because the projected benefits may not be easily valued in monetary terms. For example, there is no specifically defined value associated with benefits from ecosystem improvements, such as increased fish and wildlife populations. Accordingly, performing detailed benefit–cost analyses are not typically feasible, particularly for smaller projects. Nonetheless, we have identified several key criteria that state departments should use to evaluate cost–effectiveness, as described below. We note that the California Water Commission is in the process of developing methods for quantifying public benefits, including ecosystem improvements. The commission expects to finalize these methods in 2017. Such methods could provide lessons for other departments as they revise grant program guidelines for future rounds of bond funding.

Require All Guidelines to Include Certain Cost–Effectiveness Criteria. We find that there are several general steps that all departments should take as they consider the cost–effectiveness of projects. We note that some state departments with existing programs have taken these steps in previous grant guidelines. Specifically, we recommend that the Legislature require in budget trailer legislation that all state departments granting Proposition 1 funds adopt guidelines that include:

- Clear Assumptions About Physical Conditions and Policies. We recommend the Legislature require granting departments to establish clear baselines for grant applicants to use when identifying the benefits and costs of their projects. These baselines would identify what conditions should be assumed as having occurred in the absence of this funding. For example, when an agency solicits water supply proposals, it should require applicants to use the same assumptions about how much water would be available in the absence of the additional funding. These baselines should include assumptions about physical conditions in the future, as well as reasonably foreseeable policy changes. Specifying baselines in this way ensures easier comparison among project proposals and that project proponents cannot increase the estimated benefits of a project by selecting favorable assumptions. Moreover, establishing clear baselines allows the granting department to consistently evaluate the degree to which a project provides state–level public benefits.

- Consistent Methods to Evaluate Benefits. We recommend that the Legislature require each granting department to develop consistent methods that its grant applicants would use when estimating the benefits of their proposed projects. In some cases, such as funding for water storage, it may make sense to quantify all benefits associated with each project because the cost of performing such an analysis is likely to be small relative to the cost of each project. In other cases where such an analysis is too costly, state departments could require applicants to identify feasible alternatives and evaluate them to see if they are more cost–effective. For example, there are multiple ways of addressing the consequences of contaminated groundwater. In areas with large ratepayer bases, chemically treating the water before delivering it to customers may be cost–effective. On the other hand, in smaller communities, drilling a new well in an uncontaminated basin may be more cost–effective given the significant capital costs of building a treatment plant.

- Measures of Past Performance. We recommend that the Legislature require that one of the criteria departments consider when reviewing project proposals is the grant applicant’s performance in completing projects in the past. Measures of past performance should include how actual benefits and costs of previously funded projects match the proponent’s initial estimates. When evaluating past performance, departments will want to consider the extent to which the grantee had control of the project’s outcomes. Considering past performance can create incentives to ensure that grant applicants accurately estimate the benefits and costs of their proposed projects. This is because applicants will know that if they do not achieve the outcomes identified in their current project, their future projects may not be funded in subsequent rounds of funding.

Require WCB to Address Cost–Effectiveness Concerns Regarding Enhance Stream Flow Proposal. As indicated above, the Governor’s budget includes $39 million for WCB to implement a program aimed at increasing stream flows, such as by purchasing water or paying farmers to take land out of production. We have significant concerns over the state’s ability to ensure that the program is carried out in a cost–effective manner. These include concerns that the program might:

- Pay Excessive Costs for Water Transfers. The Governor’s budget proposes bond expenditures in each of the next five fiscal years that could include purchases of water. It is possible that the state would pay a much higher–than–normal price for purchasing long–term contracts for water, particularly during a drought. Although data on the prices paid for water transfers are limited, there have been numerous reports of record prices during the current drought. This raises the concern that if the state begins purchasing water rights this year while the drought is ongoing, it would likely face higher prices than it would in wetter years.

- Not Produce Additional Benefits. The reductions in water use resulting from spending Proposition 1 dollars might not be in addition to what would have happened absent such funding. For example, WCB reports that it would be willing to fund some water efficiency improvements—such as more efficient irrigation systems—that might have been installed anyway. This means that there would be no net increase in water availability for the investment made.

- Duplicate Regulatory Requirements. Future regulatory actions might accomplish a similar end at lower cost to the state. For example, the Governor’s budget proposes funding for SWRCB and DFW to reevaluate the amount of water that is needed to protect public trust values (such as fish) in several high priority streams. These efforts are expected to be completed in the next few years and might result in regulatory requirements that leave more water in streams without requiring state spending.

According to WCB, it plans to address some of the above concerns in the grant guidelines for the program, which are scheduled to be finalized in May 2015. However, to the extent that the final guidelines do not address these concerns, the cost–effectiveness of the program could be significantly reduced. Therefore, we recommend that the Legislature direct WCB to report at budget hearings on how it will address these concerns. If WCB’s responses are not adequate, the Legislature could pass budget trailer legislation that directs WCB to include in their guidelines specific requirements to address these concerns. For example, this could include (1) conducting a “reverse auction”—where water sellers bid to offer the lowest price—for water purchases to ensure the state gets the lowest price, (2) setting a maximum water price WCB is willing to pay to contain costs, (3) prohibiting the use of funds for projects that would otherwise occur, and (4) prohibiting water purchases in watersheds until SWRCB has completed up–to–date instream flow studies and regulations for those watersheds.

Consider Net Water Savings When Reviewing Water Use Efficiency Proposals. The DWR indicates that it intends to count water savings as a public benefit eligible for state funds when implementing the Governor’s agricultural and urban water use efficiency budget proposals. However, some of those water savings may be used by the grantee for other purposes or by other water users who would otherwise not receive water under their right. For example, a farm that transitions from flood irrigation to more efficient drip irrigation may not reduce water consumption, but may increase crop yields while using the same amount of water. In these cases, water use efficiency measures might not result in additional water being left in streams for fish species. The California Water Plan, updated by DWR in 2014, accounts for these challenges in its definition of “net water savings.” (This plan describes current and future water conditions and potential management strategies to meet demands for water.) Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature require DWR to use this definition when calculating water savings for the purpose of scoring water use efficiency proposals.

As discussed earlier, CNRA is required to review grant guidelines for consistency with the requirements of the bond. According to CNRA, it plans to actively review guidelines and provide feedback to administrating departments on selection criteria and processes. The CNRA also plans to review the grant agreements and project–selection processes of the administering departments, as well as bring in technical experts from other state departments as needed. We believe these are very positive steps in helping promote cost–effectiveness in the selection of projects. In fact, Proposition 1 requires departments to use the best available science when making decisions, such as on project selection and funding. In some cases, state staff may not be aware of the latest developments in the relevant scientific research (such as on behavioral responses to water conservation efforts). Thus, it can be valuable to bring in expertise for assistance from outside of state government. Outside expertise may be particularly important for programs that are new or where there is uncertainty around what types of projects or strategies are the most effective. As such, we recommend departments:

- Utilize Outside Experts in Developing Guidelines for Enhanced Stream Flow. The WCB anticipates funding a variety of activities to enhance stream flows, including acquisitions of water rights. In order to address some of the above concerns regarding the cost–effectiveness of the program, we recommend that CNRA bring in outside experts (such as water lawyers and academic researchers) to assist WCB in developing program guidelines. This would help ensure that the selection process is designed to identify those projects that will achieve state–level public benefits.

- Utilize Outside Experts to Implement and Evaluate Water Use Efficiency. Under the Governor’s proposal, some of the water efficiency funding would support public education to change public perception and actions, as well as support other water conservation measures. There is ongoing research on behavioral responses to various water efficiency strategies, as well as how long people continue to implement these strategies. Outside technical experts (such as academic researchers) could help DWR implement and evaluate these measures.

In addition to funding projects, the administration is proposing to use some of the Proposition 1 bond funds for various operational and administrative activities. As mentioned previously, in some instances, spending dollars on such activities can have merit. However, since some departments (such as conservancies) have a history of funding a large share of their ongoing operations from bonds, we recommend that the Legislature take actions to limit operational and administrative costs. To the extent large amounts of funding are used for operational and administrative costs, less funding would be available for constructing projects.

Specify Amount of Operational Funding for San Diego River Conservancy. The Governor’s budget proposes budget bill language that would provide the San Diego Conservancy flexibility to spend its proposed funding on state operations, capital outlay, or local assistance—with the exact allocations to be determined by the conservancy at a later date. In some instances, we recognize that departments might not have good estimates of how much of their funding they will provide as grants to local versus state departments. In such cases, it may be reasonable for the departments to have some flexibility to spend funds for either purpose. However, in order to ensure that the amount of bond funds going to operational activities rather than project costs is justified, it is important for the Legislature to understand how much of the bond funds are going towards state operations. Thus, we recommend the Legislature reject the proposed budget bill language and require the San Diego Conservancy to specify the amounts it plans to spend on state operations versus other purposes. The conservancy could request adjustments to the specific appropriation levels in future budgets as necessary.

Prior to taking actions on the Governor’s various Proposition 1 proposals, we recommend that the Legislature require the administering departments to submit staffing plans for all bond–related activities (including prior bonds as well as Proposition 1). The Governor’s budget proposes to fund a total of 158 positions (including 100 new positions) in 2015–16 to implement Proposition 1, as shown in Figure 9. The administration also identifies the need for additional positions in future years. Some of the positions requested are for new programs, while other positions are proposed for existing programs that have some staff already in place. Importantly, some departments are likely to have reduced workload in the coming years associated with administering programs funded from previous bonds, such as Proposition 84, Proposition 1E, and Proposition 50. However, only some of the administration’s proposals specify whether they took that baseline and declining workload into account when determining how many positions to request. For example, the SWRCB proposes 54 new positions largely to administer three existing programs—small community wastewater, drinking water, and water recycling—but has not yet fully explained that this number of new positions is warranted. This information is important to have in order to understand whether the proposals minimize the administrative costs of bond implementation.

Figure 9

Staff Requested in 2015–16 to Implement Proposition 1

|

Department

|

Staff Requested

|

Activities Supported

|

|

SWRCB

|

54

|

- Groundwater cleanup projects

- Stormwater management

- Water recycling

- Drinking water for disadvantaged communities

- Wastewater treatment in small communities

|

| DWR

|

43

|

- Water storage project staff support (for CWC)

- Groundwater sustainability plans and projects

- Integrated Regional Water Management

- Water use efficiency

- Desalination

- Administration

|

|

DFW

|

42

|

- Watershed restoration benefiting state and Delta

|

|

Conservancies

|

11

|

- Watershed protection and restoration projects

- Urban creek—Los Angeles River restoration

|

|

WCB

|

5

|

|

|

CNRA

|

4

|

- Various state obligations and agreements

- Urban watersheds

- Ocean Protection Council

- Administration

|

|

Total

|

158

|

|

In most cases, we find that the administration’s proposals for Proposition 1 funding further the purposes of the bond. However, there are cases where the proposals do not appear to meet key requirements in the bond. For these particular proposals, we recommend below that the administering departments report at budget hearings how their project selection processes will be consistent with the bond.

Require CNRA to Report on How Conservancy Guidelines Align With Bond Priorities. Proposition 1 requires that conservancy projects be selected competitively and address water–related purposes, such as to remove barriers to fish passage and to protect and restore aquatic, wetland, and migratory bird ecosystems. However, the Governor’s proposals related to the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy, Baldwin Hills Conservancy, and San Joaquin River Conservancy appear to conflict with one or more of these requirements. Specifically, these proposals appear to fund (1) specific projects that might not be acquired through a competitive process (such as acquisition of particular parcels of land) and (2) projects that are not primarily water–related (such as trails). The CNRA indicates that it will ensure that the conservancy grant selection processes are competitive and result in projects that primarily have a water–related purpose. In order to help ensure that the conservancy bond funds are allocated in a manner consistent with the priorities laid out in Proposition 1, we recommend that CNRA report at budget hearings this spring on its project selection process and guidelines.

Require SWRCB and DWR to Report on How Water Recycling and Desalination Guidelines Meet Bond Requirements. The Governor’s budget proposals for water recycling and desalination reflect continuations of existing grant programs operated by SWRCB and DWR. Both entities intend to use modified versions of their existing program guidelines to allocate Proposition 1 bond funds. As noted above, Proposition 1 requires that special consideration be given to new, innovative technologies in the allocation of funds. However, SWRCB and DWR’s existing guidelines do not give preference to research projects or projects that use innovative technology, and the departments have not indicated whether they intend to include such a preference. Thus, we recommend that DWR and SWRCB report at budget hearings on how they intend to modify existing grant guidelines to incorporate this requirement. This will help ensure that these proposals direct funding to the priorities described in the bond.

Since most of the bond–funded programs will be administered over a number of years, it is important for the Legislature to receive regular updates regarding the status of programs, as well as information to evaluate whether bond expenditures are meeting legislative goals and reaching outcomes cost–effectively. Below, we recommend that the Legislature take steps to (1) ensure that departments collect and evaluate data on program and project performance and (2) facilitate oversight by requiring CNRA to post additional information online and report on its progress implementing the bond.

Identify Outcome Measures Prior to Approval of Guidelines. A critical part of ensuring that adequate information is available to measure the success of individual projects, as well as programs as a whole, is to ensure that the best outcome measures are selected and reported. The bond requires administering departments to identify indicators of outcomes, which it calls “metrics of success.” However, Proposition 1 does not specify what these indicators should be, and departments are still actively in the process of identifying them.

The bond requires that grant guidelines be posted publicly 30 days prior to adoption. The Legislature could use this period, though brief, to evaluate whether the guidelines include meaningful outcome measures that will allow it to assess whether programs are likely to meet legislative goals. For example, an agency might propose to use the number of acres acquired as the outcome measure for a habitat program. However, this measure may not be sufficient to determine the actual benefit to the species the program intends to protect. In that case, the department should identify additional measures, such as estimates of species recovery.

We recommend that the Legislature pass budget trailer legislation requiring departments, prior to finalizing guidelines, to identify how the data they are collecting will allow the public and the Legislature to (1) evaluate the outcomes of projects and programs, (2) compare the reported outcomes of different projects and programs, and (3) hold state departments and grantees accountable for those outcomes.

Reserve Some Bond Funds for Third–Party Evaluations. For some grant recipients or some types of projects, it may be particularly challenging to identify and evaluate outcome measures. For instance, quantifying the benefits of ecosystem restoration activities can require specific monitoring expertise. Similarly, activities such as public information campaigns can be difficult to evaluate. In such cases, it might be valuable to bring in third–party technical experts to assist in quantifying the effectiveness of programs. This would provide an outside perspective on the effectiveness of programs and take advantage of technical expertise that grantees do not have and that the granting departments cannot provide. Thus, we recommend that CNRA reserves some bond funding to fund third–party evaluations, focusing on areas of concern or that may be difficult to measure. The CNRA could request additional funding from the bond in the future.

Require CNRA to Post Additional Information Online. Proposition 1 requires the administration to post a list of all program and project expenditures on CNRA’s website. We note that the administration currently maintains a bond accountability website, which serves as a valuable resource for the public, Legislature, and other stakeholders to find basic information on bonds passed by voters in 2006. Such information includes the projects that received funding, the amount of funding allocated to each project, and the project’s status (whether it is in progress or complete).

The CNRA indicates that it is in the process of improving the website to make information more accessible, such as by adding the ability to search for individual projects. The agency also anticipates posting information about program outcomes, which will represent a substantial improvement over the current website. We recommend that, in addition to the information CNRA plans to post, the Legislature approve budget trailer legislation directing the agency to include information on changes to project timelines and current project spending in order to facilitate oversight of these projects and funds.

Use Legislative Process to Oversee Project Selection and Implementation. Since the Legislature will not be selecting specific projects for bond funding—and in the case of water storage, will not be appropriating the funding—legislative oversight over the implementation of Proposition 1 will be important. An effective way of providing such oversight is through legislative hearings at important junctures in the implementation of the bond. For example, the Legislature may wish to hold oversight hearings once grant guidelines are proposed. We recognize, however, that it may not be feasible for the Legislature to conduct hearings for all grant solicitations. Thus, it may wish to focus on the larger bond allocations and the ones that are of greater legislative concern. Such allocations could include water storage, groundwater cleanup, watershed restoration programs implemented by conservancies, and the instream flow funding.

In addition to separate oversight hearings, we expect that budget committee hearings will provide another important opportunity to conduct legislative oversight. For example, in the past, departments have faced challenges completing some bond funded projects in a timely manner and have had to request reappropriations. In some cases, there are reasons beyond the administering department’s control for project delays, such as difficulty selling bonds due to the state’s financial condition or poor weather. In other cases, however, frequent project delays might be a sign of administrative problems or unexpected barriers. In either case, when departments seek reappropriations, we recommend the Legislature inquire about the status of projects and address any challenges causing project delays. Such information could be useful in prompting changes that could get those projects back on track, as well as to inform how future funding programs could be better implemented.

Require Annual Report by CNRA on Bond Funded Activities. In addition to the information provided online and in oversight hearings, we find there would be value to the Legislature in receiving an annual report on Proposition 1 summarizing funded activities and outcomes. Given the number of departments with roles in implementing Proposition 1, we think it would be best to have one central entity be responsible for regularly reporting on bond activities and outcomes. Recognizing the role CNRA already plays in overseeing almost all the departments involved, the agency is a logical choice for this responsibility. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature pass budget trailer legislation requiring CNRA to complete an annual report on Proposition 1 bond activities over the life of the bond. In order to help inform legislative budget hearings on Proposition 1, we recommend that this report be released along with the Governor’s January budget proposal.

Specifically, these reports should provide summaries of major activities, accomplishments, challenges, and outcomes. They should also list appropriations and encumbrances on a program level, as well as grant awards and expenditures on a project level. This level of information will (1) serve as a consolidated, single source of information on the implementation of Proposition 1, (2) facilitate legislative engagement and oversight, and (3) exceed what will be included on the administration’s website, such as a discussion of accomplishments and challenges.

Proposition 1 provides the state with an opportunity to improve its water–related infrastructure. If implemented effectively, the projects funded with Proposition 1 bond monies could help the state make significant progress towards achieving a variety of water–related goals, such as improving access to clean, safe, and reliable water supplies and restoring habitat throughout the state. Toward that end, this report provides a number of specific recommendations designed to ensure that bond funds are targeted to the most cost–effective projects and that there is adequate oversight and evaluation of those projects. Figure 10 summarizes our recommendations pertaining to all bond allocations, and Figure 11 summarizes our specific recommendations on the Governor’s Proposition 1 proposals.

Figure 10

Summary of Recommendations for All Allocations

|

Promote Cost–Effective Project Selection

|

- Define portion of water supply and greenhouse gas reduction benefits that are public benefits eligible for funding.

- Require state granting departments to adopt guidelines that include:

- Clear assumptions about physical conditions and policies.

- Consistent methods to evaluate benefits.

- Measures of past performance.

- Require departments to submit staffing plans for all bond–related activities.

|

|

Oversight and Evaluation During Project Implementation

|

- Review outcome measures when available.

- Require departments to identify how the data they are collecting will allow public and Legislature to:

- Evaluate the outcomes of projects and programs.

- Compare outcomes of different projects and programs.

- Hold departments and grantees accountable for those outcomes.

- Reserve some funding for third–party evaluations.

- Require CNRA website to include information on changes to project timelines and current project spending.

- Hold oversight hearings once grant guidelines are proposed.

- Use budget hearings to evaluate program progress.

- Require CNRA to provide annual written report on:

- Summaries of major activities, accomplishments, challenges, and outcomes.

- List of appropriations and encumbrances on a program level and grant awards and expenditures on a project level.

|

Figure 11

Summary of Recommendations on Governor’s Proposals

|

Issue

|

Governor’s Proposal

|

LAO Recommendation

|

|

Water Storage

|

|

Water storage—DWR

|

$3 million and 12 positions for DWR to provide administrative support to CWC for its water storage program.

|

- Require CWC to report to the Legislature on how it will determine what are state–level public benefits.

|

|