In this post, we summarize state bonds, the state’s current debt levels, and its annual debt service payments.

Background on Bonds

What Is Bond Financing? Bond financing is a type of long-term borrowing that the state uses to raise money for various purposes. The state obtains this money by selling bonds to investors. In exchange, it agrees to repay this money, with interest, according to a specified schedule.

What Do Bonds Fund and Why Are They Used? The state has traditionally used bonds to finance major public infrastructure projects such as roads, schools, prisons, parks, water projects, and office buildings. Bonds also have been used to help finance certain private infrastructure, such as housing. A main reason for issuing bonds—instead of paying for the project all at once, also known as cash financing—is that these facilities provide services over many years. Thus, it is reasonable for not only current, but also future, taxpayers to help pay for them. Additionally, the large dollar costs of these projects can be difficult to pay for all at once.

Why Does Using Bonds Cost More Than Cash Financing? One of the major downsides of using bonds is that they are costlier overall than cash financing due to the interest that has to be paid. For example, assuming that a bond carries an interest rate of 4 percent, the cost of paying it off with level payments over 20 years is close to $1.50 for each dollar borrowed—$1 for repaying the principal amount borrowed and about $0.50 for interest. This cost, however, is spread over the entire 20-year period. So, the cost after adjusting for inflation is considerably less—about $1.10 for each $1 borrowed. The cost of repaying bonds depends primarily on the interest rate and the time period over which the bonds have to repaid (also known as the term). The state’s interest rate on bonds is generally determined by broader financial market conditions, including rates on U.S. Treasury notes and investor perceptions of the state’s creditworthiness.

What Types of Bonds Does the State Sell? The state sells three major types of bonds to finance projects. These are:

- General Obligation (GO) Bonds. GO bonds must be approved by the voters and their repayment is guaranteed by the state’s general taxing power. Most of these are directly paid off from the state’s General Fund, which is largely supported by tax revenues. Some, however, are paid for by other revenue sources, with the General Fund only providing back-up support in the event the revenues fall short. One major example is commercial vehicle weight fee revenue, which is used to pay debt service on transportation bonds.

- Lease-Revenue Bonds. These bonds are paid off from lease payments (primarily financed from the General Fund) by state agencies using the facilities the bonds finance. These bonds do not require voter approval and are not guaranteed by the state’s general taxing power. As a result, they have somewhat higher interest costs than GO bonds.

- Traditional Revenue Bonds. These also finance capital projects, but are not supported by the General Fund. Rather, they are paid off from a designated revenue stream generated by the projects they finance—such as bridge tolls. These bonds also are not guaranteed by the state’s general taxing power and do not require voter approval.

Overview of State Debt

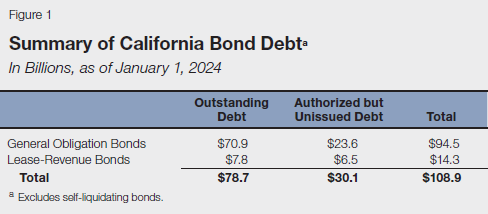

How Much Debt Does California Currently Have? As shown in Figure 1, California has a total of about $79 billion in outstanding bond debt—the vast majority of which is from GO bonds. In addition, the Legislature and voters have authorized another $30 billion in bonds that have not yet been issued (sold). As these bonds get issued in future years, they will increase the state’s outstanding debt. On the other hand, the debt that is currently outstanding will slowly get paid off, thereby reducing debt in future years. Over the last decade, outstanding debt has been paid off at roughly the same rate as new debt has been issued, resulting in a relatively steady level of state debt (not adjusting for inflation).

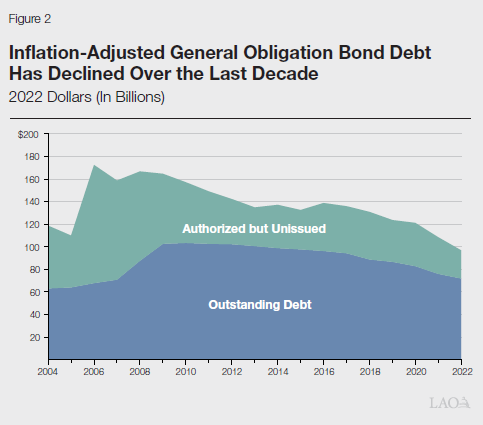

After adjusting for inflation, state GO bond debt—as well as authorized but unissued debt—has declined over the last decade, as shown in Figure 2. This decline followed a period in the mid-2000s when voters authorized several large bonds and, as a result, the state’s overall debt level increased significantly.

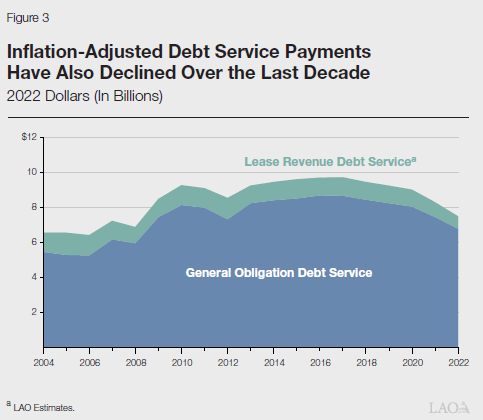

How Much Debt Service Does the State Pay Each Year? Regular payments made to bond investors—including both interest and principal—are known as debt service payments. As shown in Figure 3, the state currently pays nearly $8 billion per year in bond debt service payments—mostly for GO bonds. These payments have decreased slightly over the last decade, after adjusting for inflation.

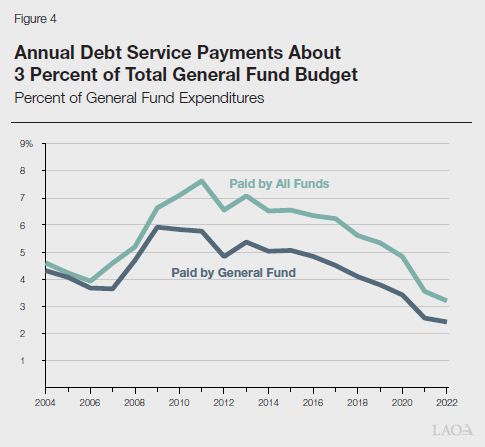

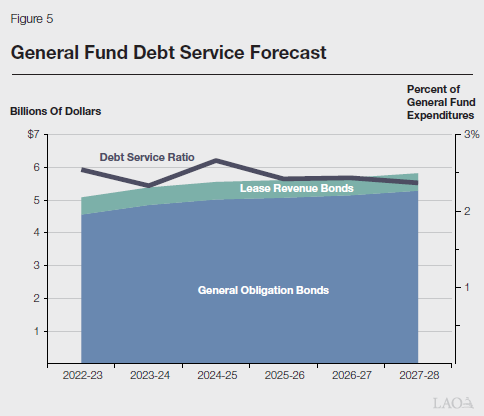

Debt service payments are sometimes evaluated as percentage of a state’s overall budget. This is sometimes known as the debt service ratio (DSR). As shown in Figure 4, total annual debt service in 2022-23 was about 3.2 percent of General Fund expenditures, but only about 2.5 percent when looking only at the portion of debt service payments that are paid from the General Fund. On both measures, the DSR was the lowest it had been over the last couple of decades.

How Much Will Debt Service Payments Change Over the Next Few Years? We forecast modest growth in annual General Fund debt service payments over the next few years, as shown in Figure 5. Since the overall state budget is expected to grow during the same period, we project the DSR will remain relatively flat. This forecast does not assume debt service payments associated with Proposition 1, which will go before the voters in March. If Proposition 1 passes, we estimate the state would have about $100 million to $200 million in additional debt service payments by 2027-28—adding less than 0.1 percent to the state’s DSR. (Annual debt service payments would grow to over $400 million in the following years.)