LAO Contact

January 17, 2017

Understanding the Veterans Services Landscape in California

- Introduction

- The Demographics of California’s Veterans

- Overview of Services Available to Veterans

- Provision of Specified Services to Veterans

- Issues for Legislative Consideration and Opportunities to Improve Service Delivery

Executive Summary

Supplemental Report Language Required LAO to Report on Veterans Service Landscape in California. A statement of legislative intent adopted by the Legislature during deliberations on the 2016–17 budget package directed the Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) to report on the role of the veterans homes in the 21st century. In light of data constraints, the supplemental report language was revised to require the LAO to report on the current veterans service landscape in California—including services in the state’s veterans homes and services outside the veterans homes (“in the community”). Specifically, the LAO was directed to review federally and state–funded services related to four service areas of legislative interest: long–term care, mental and behavioral health, transitional housing, and employment assistance.

Federal and State Governments Provide a Wide Array of Veterans Services Within the Veterans Homes and in the Community. Qualified veterans have a variety of federally and state–funded options for long–term care, mental and behavioral health, transitional housing, and employment assistance. The state’s veterans homes provide independent living and long–term care services to about 2,500 California veterans. Veterans may also use federal veterans benefits to finance private long–term care. Mental and behavioral health care is available to eligible veterans through the federal Veterans Health Administration, a division of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Residents of the veterans homes may also access basic mental and behavioral health services at the homes. Both the state and federal governments offer a variety of options for homeless veterans or veterans looking for affordable housing, including the Transitional Housing Program for homeless veterans located at the West Los Angeles veterans home. For veterans looking for employment assistance, the state administers several federal grants targeted at veterans through the Employment Development Department.

Legislature Has Opportunity to Improve Service Delivery Within the Veterans Homes. In our review of the services offered by the veterans homes, we found that: (1) the longest wait–lists at the homes are for the highest levels of long–term care and (2) the homes have limited capacity to serve veterans with complex mental and behavioral health needs. If the Legislature is interested in improving service delivery at the veterans homes, it may wish to take action to reduce and prioritize wait–lists, restructure the levels of care offered at each home, ensure staffing ratios are appropriate for residents with complex needs, and address staffing challenges at all levels.

Introduction

Supplemental Report Language Required LAO to Report on Veterans Service Landscape in California. A statement of legislative intent (known as “supplemental report language”), adopted by the Legislature during deliberations on the 2016–17 budget package, directed the Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) to report on the role of the veterans homes in the 21st century by March 15, 2017. As originally intended, this language would have required the LAO to produce a forward–looking analysis on how the needs of veterans in California will change over time and whether the state’s veterans homes will be able to meet the anticipated needs—to the extent such a report was feasible given the availability of data to project veterans’ future needs. Based on our review of available data and discussions with the California Department of Veterans Affairs (CalVet), we concluded that there is currently not sufficient data to reasonably project the future needs and preferences of California’s veterans, as desired initially by the Legislature.

Reporting Language Revised in Light of Data Constraints. Given the data constraints, we participated in discussions with legislative staff and the administration to refocus the report requirement. It was agreed that we would report, by the original due date of March 15, 2017, on: (1) the demographics of California’s veterans, (2) an overview of existing services provided to veterans in the veterans homes and outside of the homes (“in the community”) based on four specified service categories, and (3) possible recommendations to improve service delivery to the veteran population in California. The four service categories of particular interest are: long–term care, mental and behavioral health, transitional housing, and employment assistance. We were directed to focus on state and federally funded veterans services and to base our research on a sample of veterans homes and the surrounding community. Together with legislative staff and the administration, we selected the veterans homes in Yountville (Napa County), West Los Angeles (Los Angeles County), and Redding (Shasta County) for our sample. We conducted visits at these veterans homes and interviews with the County Veterans Service Offices (CVSOs) of these counties.

In this report, we describe the demographics of California’s veterans and provide a high–level overview of veterans services provided in the homes and services provided in the community. We then review the federal and state services available to veterans for long–term care, transitional housing, mental and behavioral health, and employment assistance and provide our findings. Finally, we highlight issues for legislative consideration and offer options to improve service delivery within the veterans homes.

Back to the TopThe Demographics of California’s Veterans

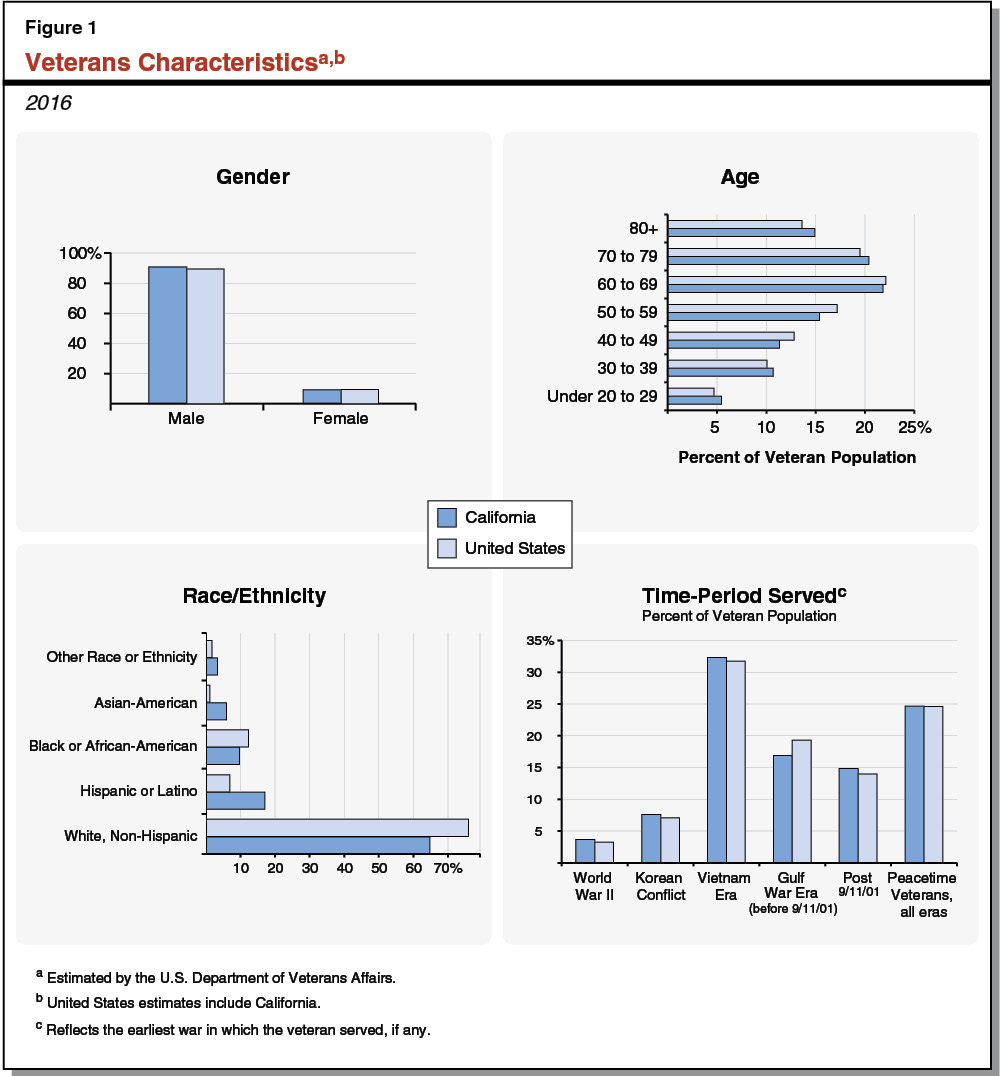

California’s Veterans Share Many Demographic Characteristics With Veterans Nationwide. Of the estimated 21 million veterans in the United States, about 1.8 million veterans live in California—more than in any other state. As shown in Figure 1, the demographic characteristics of California’s veterans are generally comparable to the demographic characteristics of veterans nationwide in terms of gender, age, and time–period served. As of 2016, it is estimated that over 90 percent of California’s veterans are male, more than half of California’s veterans are over age 60, and veterans who served in the Vietnam war make up the largest share of the veteran population. Younger veterans—those who began service after September 11, 2001—make up 15 percent of California’s veteran population.

However, California’s Veterans Differ From Veterans Nationally on Race/Ethnicity and Income. Deviating from national trends, California’s veterans are more racially and ethnically diverse than veterans across the United States. For example, 17 percent of California veterans identify as Hispanic or Latino, compared to only 7 percent nationally. California is also home to roughly one–third of the nation’s Asian–American veterans, who make up 6 percent of California’s veteran population (compared to 1 percent of the veteran population nationwide). In addition, the median household income for California’s veterans in 2014 was estimated to be about $74,000, about $12,000 higher than the estimated median household income for Californians overall. According to data from 2015, 7.5 percent of California’s veteran population was below the poverty level, compared to 14.3 percent of Californians overall. (We note that the income data reflect the median income of households containing veterans, and therefore do not necessarily reflect the median income of veterans themselves. In addition, the income data are estimated from the American Community Survey, in which veterans must choose to identify themselves as veterans—this may lead to underreporting of veterans.)

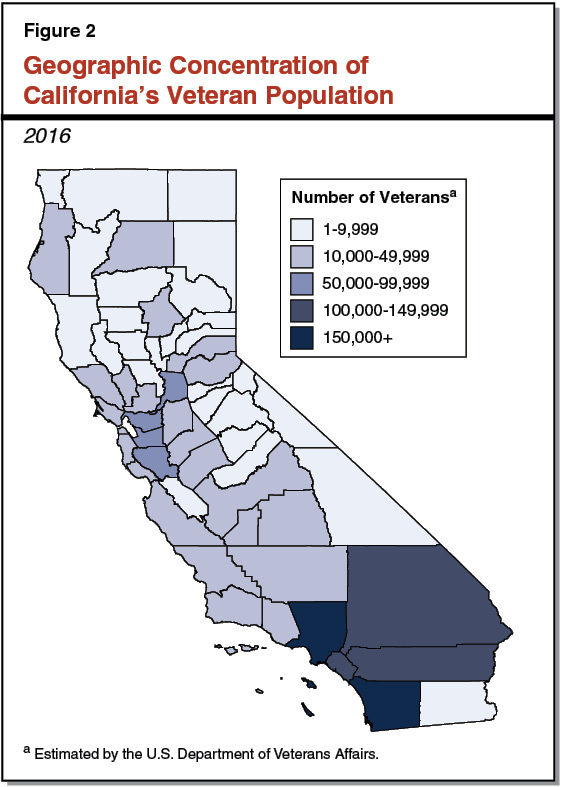

Largest Share of California’s Veterans Live in Southern California. California’s veterans live throughout the state, but concentrate in a few key areas. As shown in Figure 2, the largest share of veterans live in Southern California counties. Los Angeles County is home to the most veterans (approximately 330,000) and San Diego County has the second–most veterans of any California county (approximately 230,000). Sacramento County has the most veterans of any Northern California county (approximately 90,000), followed by Santa Clara, Alameda, and Contra Costa Counties, with about 60,000 veterans living in each county.

Overview of Services Available to Veterans

In this section, we provide a high–level overview of key federally and state–funded services provided to veterans within the veterans homes and in the community. This section does not provide an exhaustive list of federally and state–funded services, but rather highlights several major benefits, including long–term care through the veterans homes, health care, and disability compensation. In a subsequent section, we provide a more in–depth analysis focusing on the four service areas of legislative interest.

Services in Veterans Homes

The state of California runs eight veterans homes for eligible veterans to receive residential or long–term care. (Refer to Figure 3 to see the location of veterans homes and the years residents were first admitted at each home.) The veterans homes are designed to serve older or disabled veterans, whose needs range from independent living with minimum supervision to advanced medical care for residents with significant disabilities. The homes provide medical care, meals, personal care services, therapeutic activities, recreational events, and some transportation for residents. In a later section, we provide a detailed discussion of the long–term care, mental and behavioral health, transitional housing, and employment services available at the homes.

State Law and Administrative Regulations Set Eligibility Requirements, Admissions Priorities for Veterans Homes. State law provides broad guidelines for who is eligible to live in a veterans home—generally, residents of California who are aged or disabled, and discharged from active duty under honorable conditions (that is, without a dishonorable discharge). CalVet has adopted further rules and regulations to guide who is eligible to live in a veterans home. These administrative rules generally restrict admission to veterans who are 55 or older—or, at any age, veterans who are homeless or have a disability. (We note that non–veteran spouses may also be admitted to the veterans home if they meet certain criteria, per state law.) Regulations also state that the veterans homes have the right to deny admission to veterans with behavioral concerns who would threaten the safety and security of other residents, or veterans requiring specialized care beyond what is provided at the homes.

Once deemed eligible, veterans are admitted to the homes on a first–come, first–served basis. If there is not a bed available, veterans may be placed on a wait–list in the order in which they applied. State law and regulations, however, prioritize certain veterans for admissions, as follows:

- State Law Prioritizes Distinguished, Wartime Veterans for Admission. Medal of Honor recipients and former prisoners of war are prioritized over all other veterans for admission to the homes. Wartime veterans are prioritized over veterans who served solely during peacetime.

- Regulations Prioritize Veterans With Various Hardships for Admission. Regulations state that the homes may take into account veterans’ social and economic hardship, age, and disability needs, and prioritize them for admission accordingly. These factors generally allow homeless veterans to be placed for high–priority or urgent admission.

Veterans Homes Serve Mostly Older Veterans. Like most long–term care services, the veterans homes primarily serve older veterans. In July 2016, about 80 percent of veterans home residents were over the age of 65 and 34 percent were over age 85. Most veterans home residents (77 percent) served in World War II, Korea, or Vietnam, with Vietnam–era veterans making up the largest share (32 percent). The racial and ethnic makeup of the veterans homes is less diverse than California’s overall veteran population, with 85 percent of veterans identifying as white (compared to 77 percent of all California veterans).

Veterans Homes Funded by State and Federal Sources, Some Veteran Out–of–Pocket Costs. The veterans homes received $315 million General Fund in 2016–17 to fund the homes’ daily operations and care for residents. As shown in Figure 4, about $90 million of this amount is estimated to be offset by reimbursements from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (USDVA), Medi–Cal, and Medicare, and about $25 million is estimated to be offset by “member fees” charged to the veterans home residents. Member fees for veterans home residents are calculated as a percentage of the resident’s annual income—ranging from 47.5 percent for independent living to 70 percent for skilled nursing care. Residents with very low or no income do not pay member fees. (At the time of this report, CalVet was in the process of revising regulations that limit the amount of fees the home may collect based on the resident’s income.) In addition, residents who have a significant disability incurred or aggravated during service (that is, a service–connected disability rating of 70 percent or higher, which we describe later in this report) do not pay a share of cost because the veterans homes receive an enhanced federal reimbursement rate for their care. In September 2016, veterans home residents across all homes paid—on average—about $1,000 in monthly member fees. Eight percent of residents across all homes were exempt from paying member fees that month because they had low or no income or were associated with the enhanced federal reimbursement rate.

Figure 4

Veterans Homes Funding and Reimbursements

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2016–17 |

|

|

General Fund |

$315 |

|

Offsetting Reimbursementsa, b |

|

|

USDVA (federal funds) |

–71 |

|

Medi–Cal (federal funds) |

–11 |

|

Medicare (federal funds) |

–9 |

|

Member fees |

–25 |

|

Net Total, General Fundc |

$199 |

|

aProjected by the California Department of Veterans Affairs. bReimbursements are returned to the General Fund and shown as negative amounts. cGeneral Fund appropriation minus projected reimbursements. USDVA = United States Department of Veterans Affairs. |

|

Services in the Community

A wide range of veterans services are provided in the community, largely funded by the federal government. (We broadly define community services in this report as those provided outside of the veterans homes.) These federal services are administered through USDVA. (In addition to federal services designed specifically for veterans, veterans may access a number of veterans–focused services provided by community–based organizations or local governments, which vary regionally. Veterans may also access state and federal services not specifically designed for veterans, such as Medi–Cal for health care. These groups of services are beyond the scope of this report.) Below, we provide an overview of key federal veterans benefits and eligibility, and discuss how the state connects veterans to these federal services in the community. (While there are state services targeted to veterans that are provided in the community, these are much less extensive than the federal benefits and services. We discuss these state services in a subsequent section focused on the four service areas of interest.)

A Veteran’s Disability Rating Affects Federal Benefits

Many federal veterans benefits depend on a veteran’s “service–connected disability” rating. A service–connected disability is defined by the USDVA as a physical or mental disability that was incurred or aggravated while in training or active duty. Examples of such conditions include chronic back pain, amputations, traumatic brain injury, depression, and post–traumatic stress disorder. In addition, some veterans are presumed to have been exposed to harm during active duty (for example, former prisoners of war or veterans exposed to certain herbicides in Vietnam) and are presumed to have a service–connected disability. Once a service–connected disability has been established, the federal government rates the veteran’s disability from zero percent to 100 percent in increments of 10 percentage points. A higher service–connected disability rating will lead to more generous federal benefits for that veteran.

Eligible Veterans Receive Health Care From Federal Veterans Health Administration

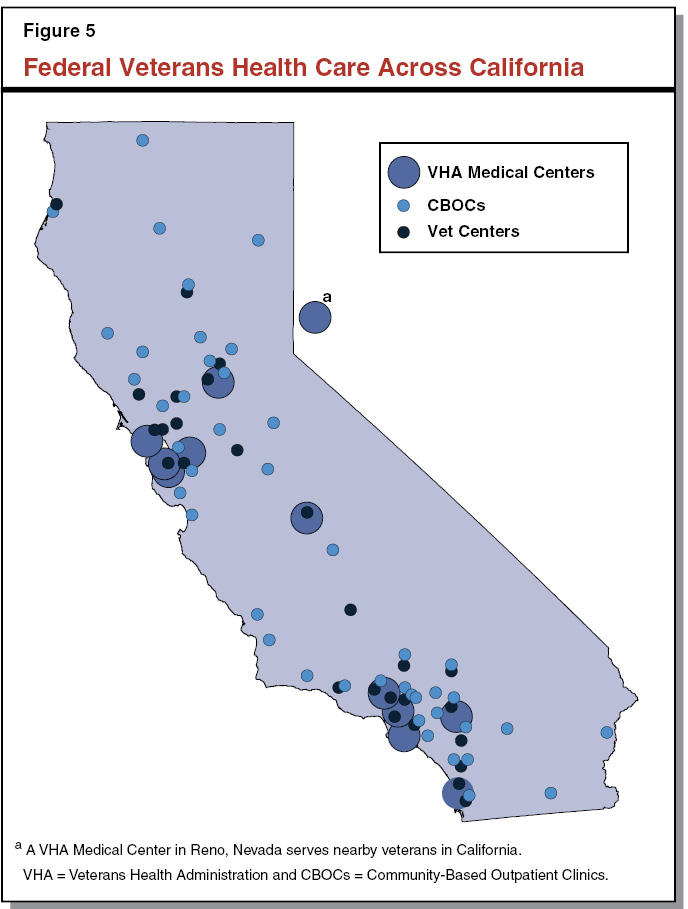

Federal Health Care Centers for Veterans Located Across the State. The federal government provides health care to eligible veterans (eligibility is discussed below) through the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), a division of the USDVA. The VHA runs medical centers with in–patient care capacity, community–based outpatient clinics (CBOCs), and service centers that help veterans and their families transition to civilian life (“Vet Centers”). These services are typically organized at the regional level as a “VA health care system.” Figure 5 displays the locations of VHA medical centers, which are generally the hub of regional VA health care systems, and the locations of the CBOCs and Vet Centers. Of California’s 1.8 million veterans, about 750,000 are enrolled in VHA, and approximately 470,000 received care from a VHA facility in 2015. Veterans not served by the VHA may access health care through other systems and insurers, such as an employer–sponsored health plan, health insurance purchased through Covered California, or Medi–Cal.

Federal Government Prioritizes Health Care for Certain Veterans. To be eligible for VHA health care, a veteran generally must have served on active duty—full–time military service—for two continuous years (or the full period of service for which they were called to duty) and have a service–connected disability. Veterans with a low service–connected disability rating may qualify for VHA health care if their income falls below a certain threshold. Health care provided by the VHA—other than the counseling services provided by Vet Centers—is not available to veterans dishonorably discharged from the military. Once deemed eligible, the VHA places veterans in one of eight priority groups generally based on the severity of the veteran’s service–connected disability, receipt of other federal benefits, and special veteran status (for example, Purple Heart medal recipient). The VHA fully funds the health care of some veterans—typically those in the higher priority groups—while others have required co–pays.

Federal Government Provides Disability Compensation, Pension to Eligible Veterans

Federal monetary benefits—in the form of disability compensation and pension—are the second–most utilized federal veteran benefit in California, after health care. In 2015, about 355,000 veterans in California received federal disability compensation and over 28,000 California veterans received a pension, with an average disability compensation and/or pension benefit of about $17,000 (including annual and one–time retroactive payments). To qualify for disability compensation, a veteran must demonstrate he or she has a service–connected disability. To qualify for pension, a veteran must meet some active duty service requirements and be over 65 with limited income or a significant disability. Veterans who are eligible for disability compensation or pension and require assistance with certain activities of daily living (ADLs)—such as bathing, feeding, or dressing—may also receive an additional monetary payment referred to as “aid and attendance” of potentially several hundred dollars monthly. In all of these cases, to be eligible for the federal benefit, veterans must not have been discharged under dishonorable conditions.

State Helps Connect Veterans to Services in the Community

State Partially Funds CVSOs to Help Veterans Apply for Federal Benefits. To apply for health care, disability compensation, pension, or other federal benefits, a veteran must complete a detailed application (“claim”) with evidence of his or her service–connected disability and proof of income. This is a lengthy process, and some veterans need assistance to gather evidence of their service–connected disability and complete the application. Sometimes, the federal government will reject the claim and the veteran will appeal the decision and, for example, add more medical evidence to his or her claim. The state provides $7.5 million ($5.6 million General Fund) each year to CVSOs, a joint state– and county–funded program to counsel veterans on available benefits, help them develop claims for benefits, provide case management services throughout the claim process, and refer veterans to other nonfederal resources. Each county has at least one CVSO and larger counties may have several. As shown in Figure 6, in 2015–16, over 400,000 veterans and their family members reached out to CVSOs for assistance, resulting in about 109,000 monetary and health care claims and $487 million in new or increased federal benefits to veterans.

Figure 6

County Veteran Service Offices (CVSOs) Utilization and Compensationa

2015–16

|

Utilization |

|

|

Veterans or family members who contacted CVSOs |

402,472 |

|

Monetary claims filed |

103,475 |

|

Health care claims filed |

5,838 |

|

Compensationb |

|

|

Average benefit amount per claimaintc |

$16,698 |

|

Value of new or increased benefit paymentsd |

$487.2 million |

|

aData from the California Department of Veterans Affairs. bIncludes disability compensation, pension, and other monetary payments. cIncludes annual award and one–time retroactive payments. dAnnualized amount of benefits awarded in 2015–16. |

|

California Transition Assistance Program (Cal–TAP) Aims to Educate Veterans About Available Benefits. Cal–TAP—administered by CalVet—adopted as part of the 2016–17 budget package, will educate veterans and their families about benefits available to them. Unlike CVSOs, which do some outreach but primarily help veterans apply for benefits, the main mission of Cal–TAP is outreach and education. Cal–TAP—currently in the implementation phase—will offer online and in–person presentations from state, federal, and community–based partner organizations to inform and connect veterans to available benefits. Outreach through Cal–TAP will focus on younger veterans as they leave military service, but presentations will also be available for veterans at all stages of life.

Back to the TopProvision of Specified Services to Veterans

In the following sections, we identify the potential service demand, the services provided in the veterans homes and in the community, and findings from our research for each of the four service areas of particular legislative interest—long–term care, mental and behavioral health, transitional housing, and employment assistance.

Long–Term Care

Long–term care, broadly defined, is assistance provided to individuals who have ongoing difficulties performing ADLs, such as bathing, dressing, eating, and toileting. Generally, people who need long–term care are older and/or have a disability that prevents them from being able to do such activities without assistance. Individuals may receive long–term care in their home from a personal care services provider or in a residential facility with on–site health care providers. In addition to the array of long–term care available to the general population, veterans have other options for long–term care. Eligible veterans may apply to live at one of the state’s eight veterans homes, or may use their federal veterans benefits or personal income to pay out–of–pocket for private long–term care.

Potential Service Demand

California’s Veteran Population Is Aging. More than half of California’s 1.8 million veterans are over the age of 60, and more than 260,000 veterans (15 percent) are age 80 or older. While not all aging veterans will need long–term care, it is likely that as individuals age, they will develop difficulties with ADLs and require some level of assistance. In addition, roughly 20 percent of veterans in California receive disability compensation, an indication that they may need some form of long–term care, regardless of age, now or in the future.

Services Provided

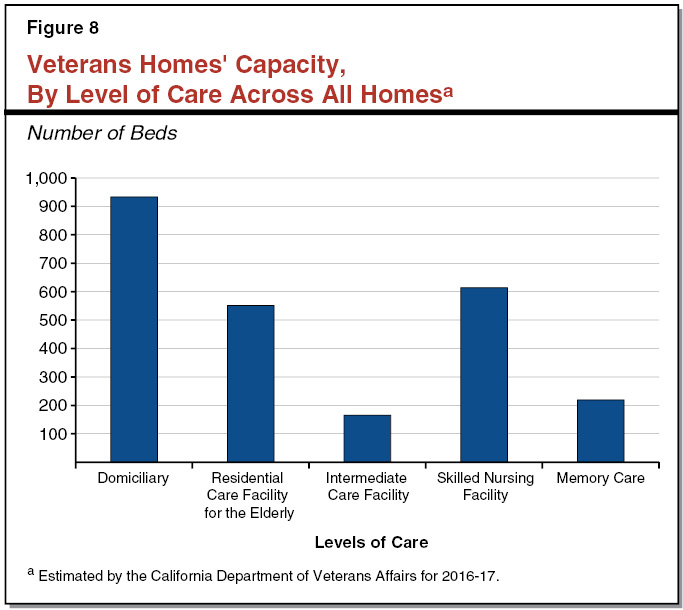

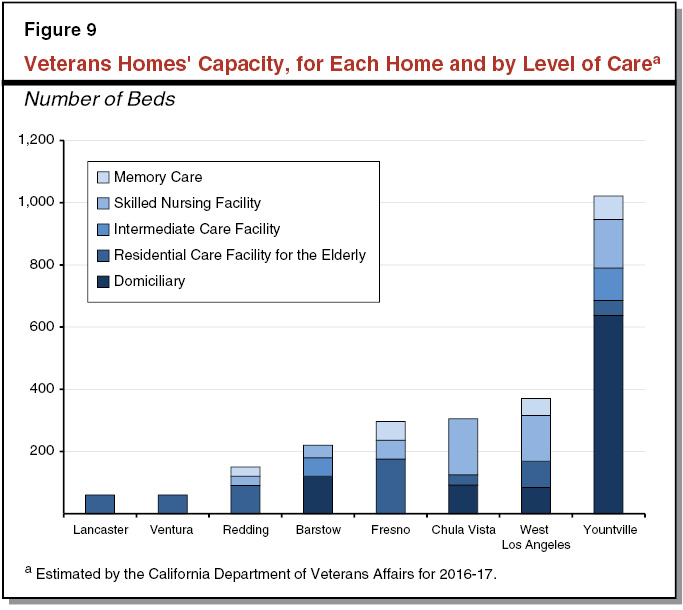

State Veterans Homes Provide Array of Independent Living and Long–Term Care Services for Eligible Veterans. As discussed earlier in this report, the state of California runs eight veterans homes. These homes provide an array of independent living and long–term care services to a total of about 2,500 veterans. The services range from independent living–style “domiciliary” care to intensive skilled nursing services for residents with dementia or mental impairment (“memory care”). We describe each level of care in Figure 7 and show the capacity for each level of care across all homes in Figure 8. Figure 9 displays the distribution of each level of care for each home. Residents receive their primary health care from each home, in addition to dental, pharmacy, and rehabilitation services. The homes also provide residents meals and offer daily activities, outings, and transportation to medical appointments for specialty care.

Figure 7

Levels of Care Offered at California’s Veterans Homes

|

Level of Care |

Description |

|

Domiciliary (Independent Living) |

Residents are able to perform ADLs with minimal assistance. Units supervised by non–nursing staff. |

|

Residential Care Facility for the Elderly (RCFE) (Assisted Living) |

Residents require some assistance with ADLs and supervision. Some care provided by nursing staff. |

|

Intermediate Care Facility |

Mid–range skilled nursing care and supervision for residents who require more assistance than an RCFE can provide, but less assistance than a SNF would provide. |

|

Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF) |

Highest level of skilled nursing care and supervision for residents who need assistance with most ADLs. |

|

Memory Care |

Designated SNF care for residents with memory impairment. |

|

ADLs = activities of daily living. |

|

Some Veterans Homes Provide Specialized Long–Term Care Services for Residents With Memory Impairment. The veterans homes currently offer 219 beds across four veterans homes (refer to Figures 8 and 9) for residents with memory impairment, such as Alzheimer’s disease. These memory care units are licensed as skilled nursing units and provide additional supervision and targeted therapeutic activities for residents with memory impairment. For example, the Redding veterans home offers a specialized “music and memory” program for residents with dementia, funded through a research grant. This program uses customized playlists for each veteran as a therapeutic and quality–of–life enhancement tool. Memory care units have the second–longest wait–list among the levels of care offered by the veterans homes.

Veterans May Access Long–Term Care Options in the Community. Veterans who are on the wait–list for veterans homes or would prefer other long–term care services, have a range of options to choose from outside of the veterans homes. Veterans may use some combination of VHA benefits, disability compensation, pension, aid and attendance, private insurance, or personal funds to pay for private long–term care. The VHA will help fund some long–term care for veterans including home– and community–based services, as well as residential care and nursing facilities that contract with the VHA. Veterans who are eligible for Medi–Cal and not receiving VHA health care may use their Medi–Cal benefits, which pay for some forms of long–term care including skilled nursing facilities.

LAO Findings

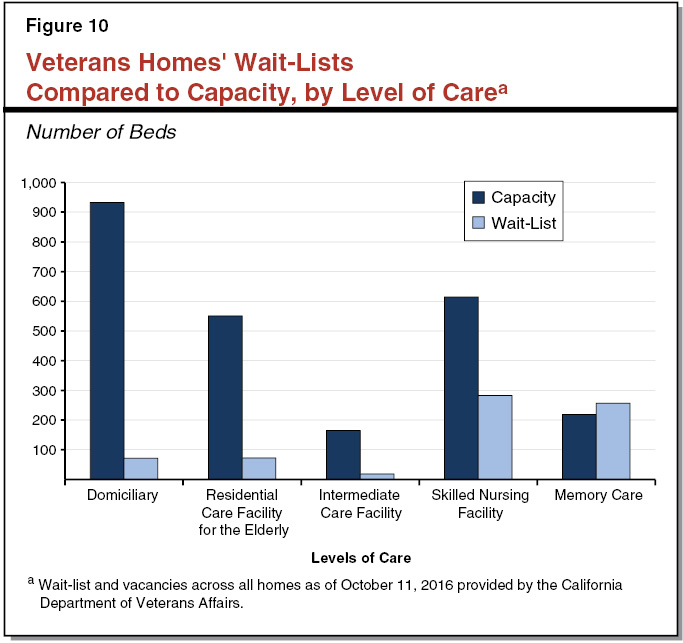

To assess the demand for each level of care across the veterans homes, we reviewed CalVet wait and vacancy data as of October 11, 2016. Figure 10 compares the wait–list of each level of care to the capacity across all homes. We summarize our findings below.

High Unmet Demand for Skilled Nursing and Memory Care Beds. As shown in Figure 10, the longest wait–lists across all veterans homes are for the highest levels of care: skilled nursing (283 veterans) and memory care (257 veterans). There are more skilled nursing beds than memory care beds. The wait–list for skilled nursing is at 46 percent of the total capacity for skilled nursing across the veterans homes, while the wait–list for memory care is above the memory care capacity across the homes—meaning that the homes could theoretically fill twice the number of memory care beds they currently offer. Demand for skilled nursing beds is highest at the Yountville home where 108 veterans are on the wait–list, followed by the Redding home where 68 veterans are on the wait–list. The Redding home has the highest demand for memory care (110 veterans), followed by the Yountville home (90 veterans).

Most Homes Have Vacant Domiciliary Beds. In our interviews with veterans homes administrators, they noted that historically, veterans have entered the homes at the domiciliary level of care, and moved to higher levels of care as their needs grew. More recently, however, veterans tend to stay in the community for as long as possible and move into the veterans homes once they need a higher level of care. This trend has placed pressure on skilled nursing and memory care capacity. This observation is reflected in the long wait–lists for skilled nursing and memory care, and the short wait–lists for domiciliary and other lower levels of care.

As Residents’ Needs Become More Acute, Demand for Skilled Nursing Beds Will Rise. As shown in Figure 10, wait–lists for the lower levels of care are not as high as those for skilled nursing care. As residents age, however, they may develop more acute care needs and eventually need skilled nursing or memory care. For veterans who are already residents of a veterans home and develop a need for a higher level of care, it is the practice for the veterans home to place that resident in the first available unit of the higher level of care. In our interviews with veterans homes administrators, they expressed concern at having some facilities with more residential care facility for the elderly (RCFE) beds than skilled nursing beds, because, under the current configuration of beds, they could not transition all RCFE residents to skilled nursing care should they need it.

Mental and Behavioral Health

Mental and behavioral health conditions include depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, substance use disorder, and post–traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Sometimes, these conditions are “co–occurring,” meaning some veterans may experience more than one condition simultaneously. Mental and behavioral health conditions are generally treatable and typically involve some combination of psychotherapy and medication.

Potential Service Demand

High Prevalence of Mental and Behavioral Health Diagnoses Among Veterans in the Community. Research shows that although most veterans return from deployment without mental or behavioral health conditions, veterans are relatively more likely to have a mental or behavioral health diagnosis than the general population. Mental and behavioral health conditions among veterans are often—but not exclusively—linked to PTSD. Some veterans may have a hard time maintaining relationships, housing, and/or employment due to mental and behavioral health conditions. The prevalence of PTSD among veterans has been studied by several research groups. A 2008 survey by the RAND Corporation estimates that about 14 percent of post–September 11, 2001 veterans who had returned from Iraq or Afghanistan had PTSD at the time of the survey. The National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study estimates the lifetime prevalence of PTSD of Vietnam–era veterans to be 31 percent for men and 27 percent for women. These estimated rates of PTSD among veterans are substantially higher than the estimate of the lifetime prevalence of PTSD among the total national population, which is roughly 7 percent.

The prevalence of mental and behavioral health conditions among veterans is also demonstrated by the comparatively high veteran suicide rate. National–level data show that veterans make up about 7 percent of the U.S. population but about 18 percent of suicides nationwide. The USDVA estimated that in 2014, veterans were 21 percent more likely to die from suicide than their civilian adult peer groups.

Services Provided

Mental and Behavioral Health Services Available to Veterans Through VHA. The federal VHA runs an array of services for mental and behavioral health treatment for enrolled veterans. Figure 11 describes the types of mental and behavioral health services available at each facility. General mental and behavioral health services, such as basic assessments and some prescription medications, are accessible to veterans through their primary care provider. Specialized mental and behavioral health services—including intensive outpatient, emergency, and inpatient care—are accessible at most VHA medical centers. Veterans may also access specialized therapy and treatment services, but not emergency or inpatient treatment, at CBOCs. Veterans may choose to access CBOC services via telemedicine instead of in–person clinic visits. The VHA also runs several Vet Centers throughout the state that provide counseling to veterans who may not otherwise be eligible for VHA services. Unlike VHA medical centers and CBOCs, services provided by Vet Centers are free–of–charge.

Figure 11

Mental and Behavioral Health Services Offered at VHA Facilities

|

Facility Type |

Services Availablea |

|

Medical Centers |

General and specialized outpatient programs. Immediate onsite emergency care. Some inpatient programs available. Medications available onsite. |

|

Community–Based Outpatient Clinics (CBOCs) |

General and specialized outpatient programs and medications available onsite and via telemedicine. |

|

Vet Centers |

Free readjustment counseling for veterans and their families. Does not require VHA health care eligibility. |

|

aReflects services generally available at each facility type, though specific services may vary by location. VHA = Veterans Health Administration. |

|

Some Veterans Homes Able to Provide Specialized Mental and Behavioral Health Services for Veterans Within Existing Resources. Data from CalVet show that 76 percent of residents at the Barstow and Chula Vista homes have a mental or behavioral health diagnosis. (Data are not available for the other homes.) Residents of the veterans homes may access some basic mental and behavioral health treatment on site through the homes’ staff of social workers, physicians, psychologists, and psychiatrists.

In addition to these basic services, some homes are able to provide more intensive treatment to veterans. The veterans home in Yountville has developed the Transitions Program within the home’s existing resources for veterans who either are: (1) prospective residents with mental or behavioral health needs beyond what the home is typically able to admit, or (2) current residents in jeopardy of being discharged from the home due to mental or behavioral health problems. The Yountville home offers between 6 and 15 domiciliary–level beds for these residents, depending on need and the availability of resources. Staff who volunteer to work with Transitions Program residents work beyond their basic duties to provide individualized therapy, supervision, structured activities, and other treatment for residents. For example, a Transitions Program resident may need staff to periodically check that the resident is not engaging in behavior that would endanger her or himself and the other residents. The Transitions Program staff could provide counseling to this resident and work with the resident to develop a plan to avoid harmful behaviors. Transitions Program residents spend about six months on average with the program, with the goal of readying the residents to live successfully at the home (outside of the Transitions Program) or in the community. We note that the scope of this program is limited, and not currently available at other homes.

LAO Findings

Veterans Homes Have Limited Capacity to Serve Veterans With Complex Mental and Behavioral Health Needs. While basic mental health services are available through the homes, they do not currently have the capacity to take in many residents with complex mental and behavioral health needs. State and federal laws and regulations require the homes to maintain certain staffing and specialized care ratios. These requirements prevent the veterans homes from admitting or retaining residents who need more services and support than staff can provide.

Our interviews with the homes’ administrators and staff indicated that residents with mental and behavioral health conditions require more staffing resources—ranging from time spent with nursing assistants to social workers and psychiatrists—than residents without such conditions. Limited staffing resources for residents with significant mental and behavioral health challenges can result in veterans being denied admission to or discharged from a veterans home. Data from the Yountville and Redding homes show that in 2015–16, 30 applicants were denied admission and 32 residents were discharged (10 involuntarily) due to behavioral health–related concerns about staffing and care disruption.

Transitional Housing and Other Options for Homeless Veterans

Transitional housing is one approach to help homeless individuals and families take a step toward permanent housing. Transitional housing programs typically provide shelter for a fixed period of time (for example, one year) to allow the participant to receive services, such as counseling and employment assistance, while he or she secures stable income and housing. We note that there are local governments and community–based organizations that provide transitional housing and services for homeless veterans (some using federal grants). Consistent with the scope of this report, however, we limit our discussion to veterans services directly administered by the federal government and state programs for homeless veterans. In this section, we describe the state and federal transitional housing options for veterans, as well as other state and federal services targeting homeless veterans or veterans in need of affordable housing.

Potential Service Demand

Homelessness Disproportionately Affects Veterans. Point–in–time data from an annual, federally sponsored homelessness count estimates that about 11,000 California veterans (0.7 percent of the estimated California veteran population) were homeless on January 30, 2015. As this count captures only homeless individuals who identify themselves as veterans, it likely underestimates the total number of homeless veterans. Despite data limitations, the estimated proportion of veterans who are homeless is higher than the estimated proportion of all individuals in California who are homeless, which was about 0.3 percent.

Services Provided

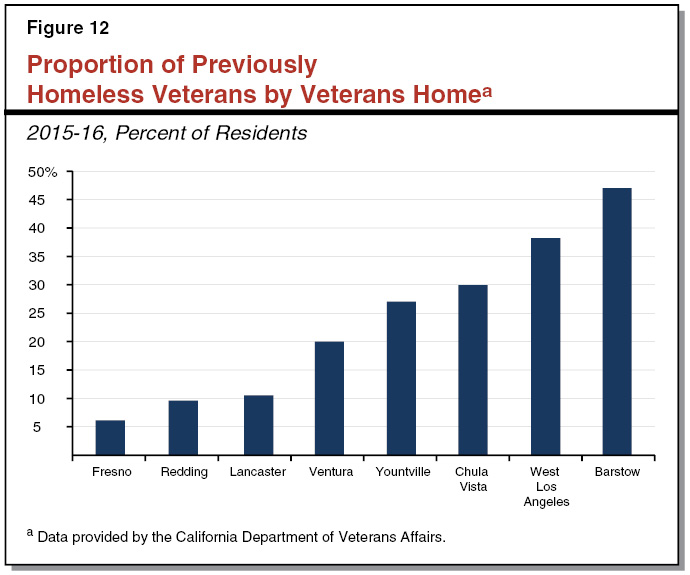

Veterans Homes Administratively Prioritize Homeless Veterans on Wait–list. As discussed previously in this report, state regulations allow the veterans homes to prioritize veterans with social and economic hardship for admission into the veterans homes, which generally allows homeless veterans to be considered for high–priority or urgent admission. Figure 12 shows the proportion of veterans at each home who self–identified as homeless immediately prior to admission (whom we refer to as “previously homeless veterans”). While the proportion of previously homeless veterans varies across the homes, on average, about one–quarter of veterans identify as previously homeless.

West Los Angeles Veterans Home Partners With Federal Government to Provide Transitional Housing Program (THP). The large proportion of previously homeless veterans at the West Los Angeles veterans home (as shown in Figure 12) is in part due to the THP located at this home. The West Los Angeles veterans home is one of three organizations that partners with the USDVA location in West Los Angeles (which owns the campus where the West Los Angeles home is located) to provide veterans with temporary housing while they look for stable housing and income. Candidates for THP are chosen after graduating from a USDVA substance use rehabilitation program on the West Los Angeles campus. The THP residents live at the West Los Angeles veterans home while they prepare to transition to life in the community by looking for housing, employment, and/or educational opportunities. Participants may access federal services on the West Los Angeles USDVA campus, including general VHA health care services, specialized mental and behavioral health care, vocational rehabilitation, and other employment assistance services.

Variety of Federal and State Housing Programs Aim to Make Affordable Housing Available to Veterans in the Community. The federal and state governments administer a number of programs that aim to help veterans transition into permanent housing, or to make permanent housing more affordable. Below, we describe three key federal and state programs.

- Federal Housing Vouchers for Veterans. Together with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the USDVA administers the Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing (HUD–VASH) program. This program allows local housing authorities with high prevalence of veterans homelessness to apply for an allocation of federally funded “housing choice” vouchers for veterans (colloquially known as “Section 8” vouchers among the non–veteran population). These vouchers generally allow veterans to find permanent housing in the community and apply the value of the voucher toward their rent payment. To be eligible for HUD–VASH, a veteran must be homeless, eligible for VHA health care, and participate in case management services and recommended treatment (for example, mental health treatment) provided by the program. Nationally, there are a fixed amount of vouchers. Since 2008, the federal government has provided approximately 16,500 vouchers to California veterans. Of the 8,000 vouchers allocated nationally in 2016, California received 1,390.

- California Veterans Housing and Homelessness Prevention Program. Proposition 41—approved by voters in June 2014—provides $600 million to the California Department of Housing and Community Development, the California Housing Finance Agency, and CalVet to develop affordable housing for veterans and their families. (The funds for Proposition 41 were redirected from previously approved general obligation bonds for the CalVet Home Loan program, which we discuss below.) By law, all Proposition 41 funds must be used to serve veterans and their families, and at least 50 percent of the funds must serve veterans with extremely low incomes (which HUD defines each year by region). As of June 2016, the state had awarded approximately $180 million of the funds to develop about 1,500 housing units through a competitive grant process. About 900 of the 1,500 units are set aside specifically for homeless veterans. As shown in Figure 13, the planned units are located throughout the state, with the most units in the Los Angeles area.

- California Home Loan Program for Veterans. The CalVet Home Loan program provides various types of home loans to eligible veterans. These loans are primarily backed by a USDVA guarantee. The CalVet Home Loan program provides veteran–specific loan services and targets veterans who may not otherwise qualify for a home loan, which may make it easier for certain veterans to obtain affordable housing. Currently, the CalVet Home Loan program is managing about 5,500 home loans (valued at about $1 billion) for veterans and their families. The program is self–funded through bond funds and loan repayments.

Figure 13

Veterans Housing and Homelessness Prevention Program:

Grants Awarded by Locationa

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Location |

Total Awarded |

Number of Housing Unitsb |

|

Bay Area |

$29 |

207 |

|

Los Angeles |

84 |

686 |

|

Inland/Orange |

22 |

205 |

|

San Diego |

17 |

188 |

|

Other |

27 |

263 |

|

Totals |

$179 |

1,549 |

|

aData from the California Department of Housing and Community Development for grant award Rounds 1 and 2, as of June 2016. bProjected. |

||

LAO Findings

With High Prevalence of Mental and Behavioral Health Diagnoses, Admitting More Previously Homeless Veterans Could Place Staffing Pressures on Veterans Homes. The USDVA estimates about 80 percent of homeless veterans nationwide have mental and behavioral health or substance use disorders. In our interviews at the veterans homes, staff indicated that previously homeless residents sometimes have a difficult time readjusting to living near other people, and often need mental or behavioral health treatment to help them transition to life at the veterans home. As we discussed previously, the veterans homes have limited capacity to care for veterans with significant mental and behavioral health challenges. If the homes begin to admit more previously homeless veterans who also have mental or behavioral health diagnoses, then staff may face challenges balancing the care of veterans with acute mental and behavioral health needs and maintaining the staffing requirements for the rest of the veterans at the home.

Employment Assistance

When veterans leave military service, they may have difficulty translating the skills they acquired to non–military jobs. Several services at the state and federal levels aim to help veterans transition back into the labor force.

Potential Service Demand

Higher Unemployment Rate Among California’s Veterans. In 2015, California had one of the nation’s highest veterans unemployment rates at 6.8 percent. The unemployment rate for California veterans was higher than the California non–veteran unemployment rate (6.0 percent). While the unemployment rate is generally high among veterans, certain veterans are disproportionally affected by high unemployment. Veterans with significant service–connected disabilities (defined as a disability rating of 60 percent or higher) have a higher unemployment rate than other veterans. Young veterans—those who served in active duty after September 11, 2001—also have a higher unemployment rate than other veterans. (We note that the unemployment rate, as measured by the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics, excludes individuals who have stopped looking for work or otherwise dropped out of the labor force.)

Service Provision

State Employment Development Department (EDD) Runs Employment Assistance Programs for Veterans. The California EDD runs a variety of employment assistance programs, some of which target veterans. These programs are generally funded by federal grants and administered through the statewide network of employment centers, the America’s Job Centers of California (AJCC). Pursuant to federal law, veterans are typically prioritized for services through the AJCC. In addition to granting priority to veterans, the state leverages two federal funding streams to support employment assistance for veterans:

- Jobs for Veterans State Grant (JVSG). The JVSG—a federal grant program—provided about $19 million in federal funds in 2016–17 for additional staffing within full–service AJCCs. Specifically, these federal funds support the Disabled Veterans Outreach Program (DVOP) and Local Veterans’ Employment Representatives (LVERs). The DVOP staff provides “career individualized services,” such as career assessments, planning, intensive job training, vocational education, and other employment–related services to disabled veterans. Data from EDD show that, as of September 2015, about 1,100 (76 percent) veterans receiving DVOP intensive services entered employment after exiting the program. The LVERs work with veterans and employers to help facilitate employment opportunities, training, and job placement for veterans.

- Veteran Employment–Related Assistance Program (VEAP). The state allocates about $5 million annually from a federal grant for VEAP, which awards grants through a competitive process to community–based organizations offering employment services targeted to veterans. Currently, 21 organizations throughout California receive VEAP funding.

Federal Government Directly Administers Some Vocational Rehabilitation and Employment Services for Eligible Veterans. The USDVA administers a vocational rehabilitation and employment program for veterans with service–connected disabilities, and general employment services for other veterans aiming to re–enter the labor force. Veterans with service–connected disabilities may receive comprehensive career assessments, vocational counseling, job training, case management, and job placement services through the Veterans Rehabilitation and Employment (VR&E) program. For veterans without service–connected disabilities, or for veterans who do not want VR&E services, the federal government offers an online job database (known as the “Veterans Job Bank”) and online training to aid veterans in their job search.

State and Federal Governments Grant Hiring Preference to Veterans. The state and federal governments use ranking systems to identify the highest qualified applicants to fill civil service positions. These ranking systems grant preference to veterans applying for most state and federal jobs. While this preference does not guarantee a veteran will be hired, veterans with hiring preference are generally moved to the top tier of applicants.

Most Residents at Veterans Homes Are of Retirement Age, Without Need for Employment Assistance. Approximately 90 percent of residents at the veterans homes are over the age of 65 (typically thought of as retirement age). Accordingly, few veterans at the veterans homes need or want employment assistance. One notable exception is the group of veterans participating in THP at the West Los Angeles home, as veterans served in that program are typically working–age and looking for stable income and housing. As part of THP, veterans participate in employment assistance programs through USDVA.

Back to the TopIssues for Legislative Consideration and Opportunities to Improve Service Delivery

In our review, we identified four key opportunities for the Legislature to improve service delivery at the veterans homes. These opportunities could improve service delivery by reducing and prioritizing the wait–lists, providing the appropriate level of care for current and prospective residents of the homes (including those with complex needs), lowering the vacancy rates, and ensuring the homes are properly staffed.

Prioritizing the Wait–List

While certain limited groups of veterans (such as Medal of Honor recipients and former prisoners of war) are prioritized for admission to the veterans homes by state statute, admission priorities have largely been established administratively through regulations. If the Legislature wishes to ensure certain groups of veterans are prioritized for admission to the veterans homes, it could codify its own admission priorities in statute. As the Legislature considers its priorities, it may wish to consider what long–term care, housing, or mental health treatment options a veteran may have in the community and prioritize admission for veterans without reasonable alternatives to the homes. Such a policy goal would likely lead the Legislature to prioritize in statute the regulations that CalVet has established administratively to prioritize veterans who are homeless, or have economic hardship that may prevent them from obtaining alternate care. Alternately, the Legislature could prioritize admitting veterans whose care the federal government reimburses at a higher rate—those receiving skilled nursing services and those with a service–connected disability rated 70 percent or higher. This would prioritize veterans with significant care needs, and also lead to increased federal reimbursements for the cost of care for such veterans. If the Legislature decides to prioritize admission for certain groups of veterans, we suggest that the Legislature consult with CalVet regarding any additional staffing needs and other budget requirements the new admissions rules could create.

Serving Veterans With Complex Mental and Behavioral Health Needs in Veterans Homes

As discussed previously, all veterans homes provide some basic level of mental and behavioral health support, but have limited capacity to assist veterans with complex mental and behavioral health needs. Veterans home residents with such needs require increased staff contact to ensure their own safety and well–being, as well as the safety and well–being of other residents. In addition, licensing requirements for veterans homes require certain staffing ratios at each level of care. Admitting more residents with mental and behavioral health needs without increasing staffing resources could place pressure on staff and jeopardize level–of–care and safety requirements at each home.

If the Legislature determines that serving veterans with complex mental and behavioral health needs is a priority, then it may wish to direct CalVet to develop new staffing standards for units that have a significant proportion of residents with mental and behavioral health needs. The new staffing standards would likely require an increased staffing ratio and additional specialized mental and behavioral health staff—along with a corresponding budget adjustment—to ensure the homes would be able to appropriately care for residents with complex needs without jeopardizing the safety and well–being of all residents of the homes.

In addition to adjusting staffing standards, the Legislature may wish to direct CalVet to develop a plan for how they would accommodate more residents with complex mental and behavioral health needs. The plan should include a strategy for where, how, and how many residents with complex mental and behavioral health needs could best be accommodated, in light of staffing and other budgeting resources and the objective of minimizing disruption to the current makeup of the veterans homes as practicable. For example, CalVet may choose to dedicate specific units or a set of beds in one or several veterans homes for residents with complex mental and behavioral health needs.

Adapting to Changing Demand for Levels of Care

Within the veterans homes, the long wait–lists for the highest levels of care (skilled nursing and memory care) and high vacancy rates for lower levels of care (domiciliary) raise questions about what flexibility the homes have to adapt to changing demand across the levels of care. Due to stricter licensing requirements for the highest levels of care, converting any existing units to higher levels of care would require legislative action to authorize unit renovations and approve budget adjustments associated with such renovations.

If the Legislature is interested in addressing the changing demand for levels of care within veterans homes, it could consider several options—each with trade–offs. The Legislature may wish to reduce wait–lists for the skilled nursing and/or memory care level of care by renovating existing units licensed for lower levels of care to accommodate higher levels of care. If the Legislature wishes to pursue this option, then it may want to consider its goals when selecting which units to renovate. For example, the Legislature may wish to minimize the cost associated with the renovations. In this case, the Legislature could prioritize converting existing RCFE units into skilled nursing facility units, which would likely require minor changes to meet licensing standards. One drawback to this approach is that most RCFE units also have waiting lists, and converting RCFE units to skilled nursing facility units would likely increase wait–lists for RCFE beds. Alternately, the Legislature may wish to prioritize renovating empty or semi–vacant domiciliary units at the Yountville home. Converting units at Yountville would be costly and require major physical changes to the buildings. As another option, the Legislature could prioritize converting units at homes where the demand for skilled nursing and memory care are highest (Yountville and Redding).

If the Legislature is interested in pursuing any of these options, then, as a first step, it could direct CalVet to provide an assessment of which homes and how many beds they could reasonably convert given the current occupancy and wait–lists at each home. This assessment should include cost estimates for the anticipated renovations associated with meeting a higher licensing standard. For proposals that could potentially displace current veterans homes residents, the assessment should also include estimates of how many residents at which levels of care would be displaced, and a proposal for how to move the veterans into appropriate accommodations with minimal care disruption, with the goal that each resident remain within their respective veterans home, if so desired.

Addressing Staffing Challenges At the Veterans Homes

Homes Report Difficulty Recruiting and Retaining Entry–Level Staff. In our interviews at the veterans homes, administrators and staff consistently noted challenges in recruiting and retaining entry–level nursing and food service staff. In areas with a high cost of living (for example, Yountville or West Los Angeles), low–wage staff may need to commute from farther away because they cannot afford to live near the veterans home, likely reducing the pool of interested potential employees. In areas where competition is high for entry–level staff, individuals may opt for other, higher–paying jobs. For example, the West Los Angeles home reports that several hospitals in the area pay higher wages for Certified Nursing Assistants than the veterans home. Since the veterans homes are staffed by public (state) employees, the homes are somewhat constrained in their ability to adjust wages to make them more competitive. In more rural areas like Redding, staff report that it is difficult to attract qualified staff amidst a regional scarcity of such staff.

Challenges Recruiting and Retaining Specialized Staff May Reduce Ability to Draw Down Federal Funds. Staffing challenges at the veterans homes are not limited to entry–level jobs. Several homes report being unable to recruit or retain specialized health care providers, such as psychiatrists and rehabilitation staff (physical therapists, occupational therapists, and speech therapists). Administrators at the homes point to two primary reasons for this challenge: salary and location. In some cases, the salaries for specialized staff are not competitive with private–sector salaries for a comparable job. In other cases, the location of the home may not be desirable to specialized staff. Sometimes, both salary and location are barriers to retaining staff. Homes that are unable to provide rehabilitation services are consequently unable to draw down federal Medicare reimbursements for rehabilitation, which can be a lucrative reimbursement source for the homes.

Review CalHR Classifications to Improve Recruitment and Retention. There are a number of initial steps the Legislature could take to address staffing challenges at the veterans homes. The Legislature could direct CalVet to survey the homes to identify hardest–to–hire positions. With this information, the Legislature could direct the California Department of Human Resources (CalHR) to remove any burdensome or unnecessary requirements that create barriers to hiring and retaining qualified individuals in the relevant state classifications. (The Legislature could direct the administration to incorporate this review as part of its ongoing Civil Service Improvement Project—an effort led by the Government Operations Agency and CalHR to review and improve state civil service rules and procedures.) Following an initial survey, CalVet could regularly submit to the Legislature recruitment and retention data so that the Legislature can consider the issue as part of the annual budget process. If positions at some homes remain hard to recruit and retain, the Legislature could consider providing homes with targeted recruitment and retention funding for hardest–to–hire positions.