LAO Contact

February 3, 2017

Improving California’s Regulatory Analysis

- Introduction

- State Regulatory Process

- Analysis Aims to Clarify Effects and Inform Decisions

- LAO Assessment

- LAO Recommendations

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

Analysis Can Help Select Preferred Regulatory Approach. The Legislature passes laws that direct agencies to implement policies, but the laws often do not identify all of the details of how those policies should be implemented. As a result, agencies evaluate different options for implementing the law and develop regulations to clarify the details. When developing regulations, agencies are required to analyze the potential effects of proposed rules—including anticipated benefits and adverse economic effects. The goal of this analysis is to help regulators evaluate trade‑offs between different options and select the approach that achieves the Legislature’s policy goal in the most cost‑effective manner.

Senate Bill 617 Established New Requirements for Major Regulations. Chapter 496 of 2011 (SB 617, Calderon) established a new process for analyzing regulations having an estimated economic impact of greater than $50 million—known as major regulations. It required agencies to develop a more extensive regulatory analysis before major regulations are proposed. In addition, SB 617 required the Department of Finance (DOF) to (1) provide guidance on the methods that agencies should use when analyzing major regulations and (2) review and comment on the analysis before a rule is proposed.

Limitations of Current Process for Analyzing Major Regulations. Based on our review of the analyses developed under the new SB 617 process, we find that some of the changes have led to improvements in the quality and consistency of agencies’ analysis of major regulations. However, we also identified the following limitations:

- Analyses of Major Regulations Do Not Consistently Follow Best Practices. In many instances, agencies did not consistently follow best practices for regulatory analysis. For example, agencies often analyzed a limited range of alternatives and did not quantify benefits and/or costs of alternatives. As a result, the likely effects of different regulatory options were often unclear, and, therefore, it is frequently difficult to know whether the proposed approaches were the most cost‑effective.

- Certain Analytical Requirements Offer Limited Value. In some cases, the existing analytical requirements appear to provide information of limited value to making cost‑effective regulatory decisions—which is the main goal of the analysis.

- No Requirement for Retrospective Review. There is no statewide requirement for agencies to regularly evaluate the effects of a rule after it has been implemented—also known as retrospective review. As a result, the Legislature and regulators might not have adequate information in the future to determine whether the laws or rules should be eliminated, modified, or expanded in order to better achieve statutory goals.

LAO Recommendations. We make several recommendations to ensure agencies provide information that can be used to support regulatory actions that implement legislative objectives cost‑effectively.

- Establish More Robust Guidance and Oversight. We recommend the Legislature direct an oversight entity to (1) develop more detailed guidance on best practices for analysis of major regulations and (2) review updated analyses when agencies make substantial changes to a major rule after it is initially proposed. The Legislature could also consider giving this oversight entity authority to reject an agency’s proposed major rule if the analysis is inadequate or does not show the rule to be cost‑effective. These oversight activities could be conducted at DOF or some newly created entity with economic and analytical expertise.

- Reduce Requirements That Provide Limited Value. We recommend the Legislature identify opportunities to reduce or eliminate analytical requirements that provide limited value for assessing trade‑offs and making cost‑effective regulatory decisions. For example, an agency could be exempt from certain requirements if (1) it demonstrates that the analysis is not necessary to adequately compare regulatory options or (2) state or federal law limit agency discretion. Reducing unnecessary requirements would free up agency resources and allow the agency to implement regulations more quickly or focus on other aspects of regulatory analysis that likely have greater value.

- Require Agencies to Conduct Retrospective Review. We recommend the Legislature consider requiring agencies to plan for and conduct retrospective reviews for major regulations. An oversight entity should be responsible for issuing guidance on best practices for conducting these reviews and overseeing the reviews. To ensure retrospective reviews are not too administratively burdensome, the Legislature could allow the oversight entity to exempt an agency from retrospective review requirements under certain conditions, such as if collecting adequate data is infeasible or too costly.

Introduction

Chapter 496 of 2011 (SB 617, Calderon) made significant changes to the way California analyzes and reviews major regulations under the state’s Administrative Procedures Act (APA). These changes were intended to promote regulations that achieve the Legislature’s policy goals in a more cost‑effective manner. In this report, we provide a brief description of California’s regulatory process, the potential value of regulatory analysis, and the recent changes made by SB 617. Although there have been some improvements in recent years, we identify some significant limitations that still remain. We provide recommendations that are aimed at addressing these limitations by ensuring that the potential effects of regulations are thoroughly analyzed and regulators are implementing the Legislature’s policy direction in the most cost‑effective manner.

Back to the TopState Regulatory Process

General Overview of Regulations

Regulations Implement State Law. Broadly, regulations are rules issued by a government authority. In many cases, the Legislature passes laws that direct agencies to implement policies, but it does not clearly identify all of the details of how the policy should be implemented. As a result, agencies have to develop regulations through a rulemaking process to clarify these details. For example, the law could direct an agency to ensure businesses and/or households reduce a certain type of pollution to a specified level. If the law does not specify exactly how pollution must be reduced, the agency will establish a regulation outlining the requirements in more detail.

The APA is state law that establishes procedural requirements that state agencies must follow when they “implement, interpret, or make specific” policies established by the Legislature through the establishment of new or revised regulations. These requirements apply to rules developed by all state agencies, unless otherwise exempted by law. For example, most regulatory activities at the California Public Utilities Commission are exempt because the commission has a separate regulatory process in place. This report focuses on regulations developed by state agencies that are subject to the APA.

APA Aims to Ensure Rules Are Consistent With State Law. The APA aims to ensure that rulemaking is transparent, agencies consider public input, and regulations are consistent with state law. There are two major types of rulemaking procedures: regular and emergency. In this report, we focus on regular rulemaking. (Emergency rules are subject to somewhat different requirements.)

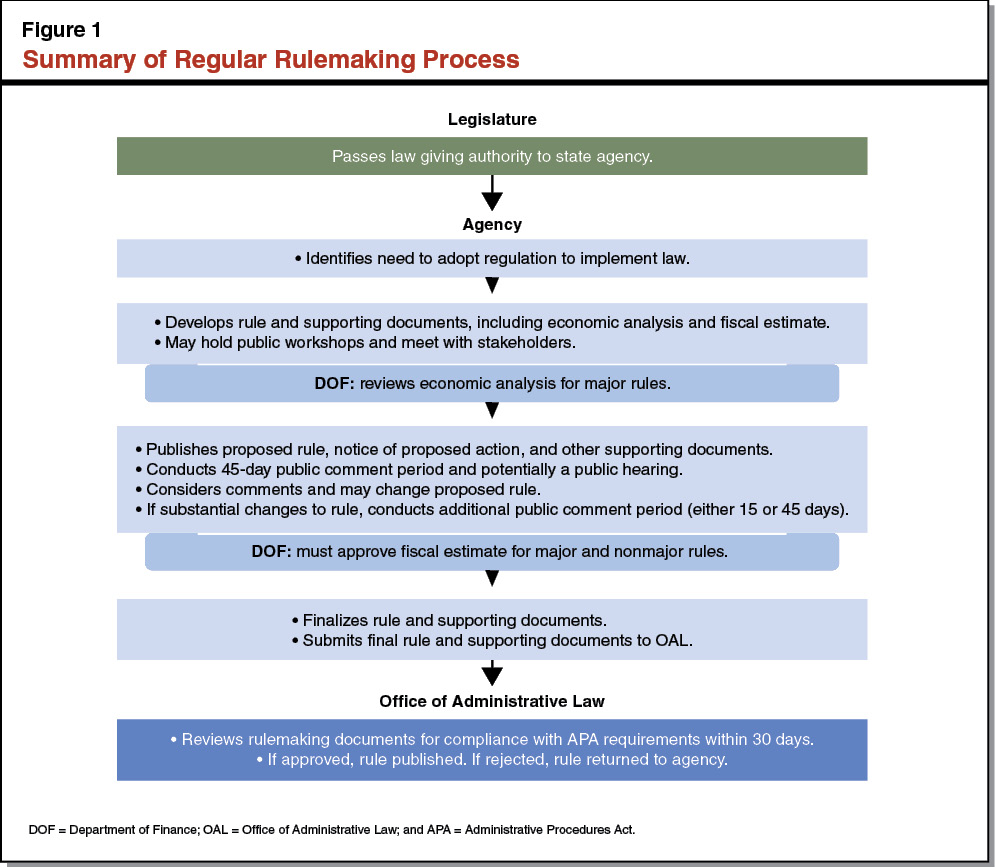

Figure 1 summarizes the key steps of the regular rulemaking process. The process begins after the Legislature passes a law that gives authority to a state agency, and the state agency decides it needs to issue a rule. In some cases, the new law could require the agency to do so. The agency then develops the regulation, as well as various additional documents as summarized in Figure 2. Once the agency has developed its proposed rule, it publishes the Notice of Proposed Action (notice) along with the other materials. For example, as we discuss in more detail below, the agency is required to complete an analysis of various effects—including economic and fiscal effects—of the proposed rule. The agency is then required to solicit public comments and respond to those comments. The agency may also modify the proposed rule, which then triggers additional public comment period(s). The agency must submit the final rule to the Office of Administrative Law (OAL) within one year of issuing the notice, and OAL has 30 working days to review the rulemaking documents to ensure that the agency fully complied with APA procedural and legal requirements.

Figure 2

Key Regulatory Documents Developed by Agencies

|

When Regulation Is Initially Proposed |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

When Regulation Is Finalizeda |

|

|

aIf there are changes after the rule is initially proposed, updates to the regulation text and economic and fiscal impact statement are also included. SRIA = Standardized Regulatory Impact Assessment. |

About 600 Regulations Submitted to OAL Annually. This total includes regular rules, emergency rules, and other minor technical adjustments to rules that are not required to go through the full rulemaking process. Many different agencies propose rules, and the number of rules proposed by each agency varies from year to year. The top ten rulemaking agencies in 2014 and 2015, in terms of the number of rules submitted to the OAL, are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Agencies With Most Rules Submitted to

Office of Administrative Law in 2014 and 2015

|

Agency |

2014 |

|

Department of Food and Agriculture |

55 |

|

Fish and Game Commission |

28 |

|

Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation |

25 |

|

State Water Resources Control Board |

25 |

|

Fair Political Practices Commission |

20 |

|

Department of Social Services |

19 |

|

Department of Health Care Services |

18 |

|

Board of Equalization |

17 |

|

California Energy Commission |

14 |

|

California Horse Racing Board |

13 |

|

Other |

366 |

|

Total |

600 |

|

Agency |

2015 |

|

Department of Food and Agriculture |

51 |

|

California Health Benefit Exchange |

31 |

|

State Water Resources Control Board |

24 |

|

Department of Insurance |

23 |

|

Fish and Game Commission |

22 |

|

Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation |

20 |

|

Occupational Safety and Health Standards Board |

18 |

|

Board of Forestry and Fire Protection |

17 |

|

Air Resources Board |

16 |

|

Board of Equalization |

15 |

|

Other |

385 |

|

Total |

622 |

Regulatory Analysis Requirements

The APA requires agencies to analyze the effects of proposed rules to help justify their merit. Below, we describe some of the APA’s major regulatory analysis requirements. We also describe some of the changes SB 617 made to the regulatory process and requirements for analyzing regulations.

General Requirements. Agencies are subject to various requirements to assess the potential effects of a regulation. For example, a proposed regulation must be based on adequate information concerning the need for, and consequences of, action. In addition, for nearly all regulations, agencies are required to provide the following information:

- Purpose of the Regulation. Agencies are required to provide an explanation for why the regulation is reasonably necessary. Agencies also have to list the specific provisions of law that are being implemented and that authorize the regulation. Senate Bill 617 added a requirement that an agency describe the problem it intends to address and how the regulation addresses the problem.

- Anticipated Benefits. Senate Bill 617 added a specific requirement that agencies identify monetary benefits and nonmonetary benefits of the regulation, such as public health, safety, and social equity.

- Adverse Economic Effects. Agencies must assess the potential for adverse economic impact on California businesses and individuals. For example, agencies are required to assess potential effects of the proposed regulation on (1) the creation or elimination of jobs within the state and (2) the creation, elimination, expansion, and competitiveness of businesses in California.

- Evaluation of Alternatives. Agencies are required to evaluate alternatives and provide reasons for rejecting the alternatives. Agencies are also required to determine, with supporting information, that no alternative approach would be more effective, or would be as effective and less burdensome to private persons. Senate Bill 617 further required that agencies determine that no alternative would be more cost‑effective to affected private persons and equally effective in implementing statutory policy.

- Fiscal Effects. Agencies are required to estimate the fiscal effects of the regulation on state and local governments.

Agencies are also required to estimate how the regulation would affect specific groups or outcomes. For example, agencies must estimate effects on small businesses and housing costs.

SB 617 Required Additional Analysis and Oversight for “Major” Regulations. The most notable changes made by SB 617 are for regulations having an estimated economic impact of greater than $50 million—known as major regulations. Senate Bill 617 required agencies to develop a more extensive economic analysis known as a Standardized Regulatory Impact Assessment (SRIA) before a major regulation is proposed. Agencies are responsible for determining whether a regulation is major. In addition, the Department of Finance (DOF) reviews agency estimates of economic impact to ensure that agencies are submitting SRIAs for all regulations with economic impacts greater than $50 million. The analyses are intended to provide agencies and the public with tools to determine whether the proposed regulation implements the Legislature’s policy decisions in a way that is cost‑effective.

To ensure agencies are conducting more rigorous analyses, SB 617 required DOF to provide guidance to agencies on methodologies for developing SRIAs. This includes methods for:

- Estimating whether a regulation will have a $50 million economic impact.

- Assessing benefits and costs of a proposed regulation, expressed in monetary terms to the extent feasible, but also other nonmonetary factors such as fairness and social equity.

- Comparing proposed regulatory alternatives with an established baseline so agencies can make analytical decisions for regulations necessary to determine the most effective, or equally effective and less burdensome, alternative.

- Determining the impact of the regulation on jobs, businesses, and public welfare.

As shown in Figure 4, agencies developed 22 SRIAs from the time the law was implemented in late 2013 through 2016.

Figure 4

SRIAs Developed for 22 Regulations Since 2014

|

Agency |

Date Submitted to DOF |

Regulation |

|

Air Resources Board |

February 2014 |

Amendments to Truck and Bus Regulation |

|

October 2014 |

Low Carbon Fuel Standard and Alternative Diesel Fuels |

|

|

April 2014 |

Oil and Gas Regulation |

|

|

June 2015 |

Zero Emission Vehicle Credit Amendment |

|

|

April 2016 |

Cap‑and‑trade |

|

|

December 2016 |

Portable Engine Airborne Toxic Control Amendment |

|

|

California Energy Commission |

December 2014 |

Water Appliance Efficiency |

|

August 2015 |

LED Efficiency |

|

|

June 2016 |

Computer Efficiency |

|

|

Department of Insurance |

January 2014 |

Mental Health Parity |

|

July 2015 |

Network Adequacy |

|

|

CalRecycle |

July 2014 |

Compostable Materials, Transfer/Processing |

|

October 2014 |

Used Mattress Recovery and Recyclinga |

|

|

Department of Industrial Relations |

October 2014 |

Return‑to‑Work Program |

|

March 2016 |

Refinery Safety |

|

|

GO‑Biz |

August 2014 |

California Competes Tax Credit |

|

Fish and Game Commission |

November 2014 |

Hunting: Nonlead Ammunitiona |

|

Department of Transportation |

March 2015 |

Affordable Sales Program |

|

November 2016 |

Electronic Toll Collections |

|

|

Health Benefits Exchange |

January 2016 |

Eligibility and Enrollment |

|

State Water Resources Control Board |

October 2016 |

Drinking Water Standards |

|

Department of Conservation |

December 2016 |

Underground Gas Storage |

|

aRegulation later determined to not exceed $50 million threshold for “major.” SRIA = Standardized Regulatory Impact Assessment ; DOF = Department of Finance; and CalRecycle = California Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery. |

||

Senate Bill 617 also established a greater oversight role for DOF. In addition to issuing guidance for agencies developing SRIAs, DOF must review the SRIA before a major rule is proposed and provide comments on the extent to which the analysis adheres to its guidance. Agencies must include a summary of DOF’s comments and agency responses to the comments when the rule is initially proposed, but the agencies are not required by law to update the analysis to reflect comments from DOF. Finally, DOF is available to provide technical assistance to agencies and has recently implemented a new training program.

Back to the TopAnalysis Aims to Clarify Effects and Inform Decisions

Below, we describe the primary reasons for analyzing regulations and some of the key methods for conducting good analysis.

Analysis a Tool for Improving Regulatory Outcomes. Regulators have options for how to implement state laws, and their decisions can have substantial costs and benefits for businesses and households in California. Collectively, agencies that have developed SRIAs so far have estimated billions of dollars in costs and benefits annually from these regulations. The primary goal of regulatory analysis is to inform the public, stakeholders, and government of the likely effects—good and bad—of various regulatory options. This information can then be used to evaluate the trade‑offs between different options and select the preferred approach. Improved regulatory decisions have the potential to increase benefits, lower costs, and ensure benefits and costs are fairly distributed.

A regulatory analysis can take different forms—each of which is meant to provide different information that answers different questions. For example, a regulator might conduct one or more of the following: (1) a cost‑benefit analysis to determine whether the overall benefits of a rule exceed the costs, (2) a cost‑effectiveness analysis to determine which approach achieves a predetermined goal for the lowest overall cost, and/or (3) a distributional analysis to determine how costs and benefits are distributed among different types of households and businesses. As discussed above, California’s analytical requirements primarily focus on cost‑effective. Regardless of which tool is used, the analysis is meant to help regulators make better, more informed decisions that implement the Legislature’s policies more effectively.

Federal Government Has Long History of Regulatory Analysis. The federal government imposes a variety of requirements on federal agencies proposing regulations. These requirements largely date back to an executive order established in 1981. Although there have been some changes over the last 35 years, the key principles have largely remained in place. For example, most agencies issuing economically significant rules are required to select the approach that maximizes net benefits to society and demonstrate that the benefits of the rule justify the costs. In addition, when an agency determines a regulation is necessary, it must design the regulation in the most cost‑effective manner to achieve the objective. Agencies must provide the analysis of its proposed and final regulations to the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), within the President’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB). OIRA is responsible for reviewing agencies’ regulations and the accompanying analyses.

Federal Guidance Describes Best Practices for Regulatory Analysis. As part of its oversight, the OMB has developed best practices for analysis. Most notably, after public input and peer review, the OMB and the President’s Council of Economic Advisors issued “Circular A‑4” in 2003—the central guidance document designed to assist regulatory agencies. Circular A‑4 identifies three key elements of an effective regulatory analysis:

- Statement of need for regulatory action.

- Clear identification and examination of a range of regulatory approaches.

- Evaluation of the costs and benefits—quantitative and qualitative—of the proposed regulatory action and the main alternatives.

It also offers more specific guidance on the basic methods that should be used for analysis. A summary of this guidance is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5

Summary of Federal Guidance for Regulatory Analysis

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Office of Management and Budget’s Circular A‑4. |

Regulatory Analysis Has Some Trade‑Offs. Although analysis has the potential to help inform better regulatory decisions, there are also trade‑offs. First, detailed analysis takes time and resources for regulators. This results in additional administrative costs that are ultimately paid for by businesses and households in the form of higher fees and taxes. Second, analysis can result in delays in implementing policies. Third, some have criticized regulatory analysis, particularly cost‑benefit analysis, as being biased against regulations that benefit health, welfare, and safety. This is because the costs of a regulation are often easier to quantify than the broad types of societal benefits that can result from such regulation. For example, the costs of a new regulation requiring a specific pollution control technology might be easier to estimate than the improved health effects of lower pollution and the value of those health benefits. To the extent decision‑makers give greater weight to effects that can be quantified, the analysis could encourage regulators to reject more stringent alternatives that achieve additional, non‑monetized benefits that outweigh the additional costs. To help avoid this potential issue, good regulatory analysis should clearly identify all significant types of benefits and costs, including those that are hard to quantify, so they are considered when making regulatory decisions.

Back to the TopLAO Assessment

We reviewed (1) the APA’s analytical requirements, (2) the SRIA guidance issued by DOF, and (3) the SRIAs that agencies have developed so far. The purpose of our review was to examine whether state agencies are conducting high‑quality analyses of major regulations and whether the analyses provide information that helps ensure regulations are implemented in a cost‑effective manner. Our review focused on analysis of major regulations because they represent a disproportionately large percentage of the overall costs and benefits of state regulations. (See the box below for a brief discussion of nonmajor regulations, which were not the focus of this report.) Based on our review, we identify several limitations, which are summarized in Figure 6 and discussed in detail below.

Oversight and Guidance for Nonmajor Regulations Less Robust

This report focuses on major regulations, but there are actually far more nonmajor rules. Although we did not review agencies’ analyses of nonmajor rules, many of the statutory requirements are the same. For example, agencies are required to adopt the most cost‑effective regulatory approaches and estimate effects on jobs, businesses, and small businesses. However, the Department of Finance (DOF) provides much less guidance and oversight over the analyses. Much of DOF’s review focuses on state and local fiscal effects. There is limited review of methods used to estimate overall benefits and costs, including costs to private parties and environmental improvements. In the future, the Legislature might want to consider changes to the analytical requirements and processes for nonmajor rules in a way that improves the quality of analysis and/or removes unnecessarily burdensome requirements. For example, once the Legislature is comfortable that the current standardized regulatory impact assessment process is leading to improved regulatory decisions and the analytical requirements are not overly burdensome, it could consider extending the process to other regulations, such as some regulations that have an economic impact of less than $50 million annually.

Figure 6

Summary of LAO Findings

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Analyses of Major Regulations Do Not Consistently Follow Best Practices

We find that the new SB 617 requirements have increased the consistency of agencies’ analyses and, as a result of the additional DOF oversight, agency analyses of proposed rules are often more robust and higher quality. Despite some improvements, however, we identified many instances where state agencies did not consistently follow best practices for regulatory analysis, such as those outlined earlier in Figure 5. As a result, the likely effects of different regulatory options are often unclear and it is difficult to know whether the proposed regulatory approaches are the most cost‑effective. We discuss the major limitations in more detail below.

Benefits and Costs of Alternatives Not Quantified. The costs and benefits of regulatory options—including the preferred approach, as well as alternatives—are often unmeasured or unclear. This makes it difficult to determine why the proposed regulation is preferable to alternatives. For example, the California Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery’s SRIA for the Compostable Materials regulation—which made changes to the way solid waste facilities must handle compostable materials—did not quantify the environmental benefits of any of the options it considered. This makes it difficult to assess the trade‑offs between the different options. In addition, the SRIA for the Air Resources Board’s (ARB’s) revisions to the Bus and Truck Regulation—which delayed requirements for truck owners to install new pollution control technologies or purchase cleaner engines—did not clearly quantify how alternatives to the proposed rule would affect industry costs or the level of air pollution emissions.

Limited Range of Alternatives Analyzed. In most cases, agencies have options for how they can implement a law, such as how stringent a requirement to impose, as well as what specific rules to impose. State law directs agencies to describe reasonable alternatives and the agencies’ reasons for rejecting those alternatives. In our view, SRIAs generally included an analysis of too few alternatives. As a result, agencies might have ignored some potentially viable alternatives. Most SRIAs included an examination of two alternatives to the proposed regulation. This may be reasonable in some cases where limited feasible alternatives exist. In most cases, however, an analysis of a greater range of alternatives could generate valuable information about which approach is the most cost‑effective or generates the greatest net benefits. For example, additional analysis of the following types of alternatives could help inform the agency’s action:

- Subparts of a Regulation. Some regulations are complicated and multifaceted with multiple distinct components. Yet, SRIAs did not always include an analysis of these distinct components of a regulation. For example, the SRIA for ARB’s extension of the cap‑and‑trade regulation did not include an analysis of the effects of specific parts of the program, such as linking the state’s program with Ontario. Therefore, the degree to which linking with Ontario would affect the overall costs and benefits is unclear.

- Different Stringencies. Some SRIAs evaluated a limited range of different stringencies. For example, the State Water Resources Control Board proposed a new drinking water standard for 1,2,3‑Trichloropropane—a chemical that was not previously regulated. The SRIA included a comparison of the proposal to two alternatives: do nothing (not imposing a new standard) and a slightly less stringent standard than the proposed regulation. It would have been helpful to estimate the costs and benefits of a broader range of feasible standards—such as a more stringent standard and additional less stringent options. This would provide a better understanding of trade‑offs associated with a broader range of feasible options which could be used to ensure the proposed standard is the best option for meeting the statutory goals.

- Alternatives Outside the Scope of the Rulemaking. Some regulations were not compared to alternatives outside the scope of the regulation. For example, the ARB’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) regulation aims to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by reducing the carbon content of fuel. The SRIA did not include a comparison of the costs of LCFS to other policies that can reduce GHG emissions, such as cap‑and‑trade or more stringent vehicle efficiency standards. Comparing a regulation to options outside the scope of the rulemaking is particularly important when agencies have broad authority to issue multiple regulations to achieve a particular goal. Such authority has been given to the ARB to regulate air pollution and GHG emissions. However, this type of authority is relatively rare in California.

Future Benefits and Costs Not Discounted. It is a standard analytical practice to weight benefits and costs that occur in the future less than those that occur more immediately. To help policymakers evaluate regulations that have benefits and costs that occur at different times, analyses typically use a method known as discounting—whereby future benefits and costs are adjusted downward based on how far in the future they occur. Agency SRIAs did not always include discounted future benefits and costs. For example, the California Energy Commission (CEC) energy efficiency standards for computers and monitors were expected to increase initial equipment costs, but generate future consumer savings from lower energy bills. However, the future savings were not discounted. As a result, the analysis overstates the overall benefits of the efficiency rule.

Limited Assessment of Uncertainty. For any regulatory approach that is adopted, the exact consequences of the regulation are uncertain. Therefore, it can be important to identify a range of outcomes that could occur and assess the likelihood of each outcome—referred to as sensitivity analysis. This provides the agency and the public with a better understanding of the risks—both positive and negative—of a particular approach. Several agencies had little or no analysis of uncertainty in the SRIA. For example, the California Department of Transportation’s (Caltrans’) analysis of the Affordable Sales Program—a program to dispose of surplus residential property owned by Caltrans—did not estimate how benefits would differ under different assumptions about future real estate property values, which can be subject to substantial uncertainty. A sensitivity analysis that assessed the benefits under different property value assumptions could have, for example, provided information about whether there were scenarios under which the proposed approach would have yielded insufficient benefits to justify the costs.

Distributional Analysis Often Lacking. There is often limited discussion of how the benefits and costs of the regulation would be distributed among different communities and households. Distributional effects might be an important consideration when evaluating alternatives if either benefits or costs disproportionately accrue to certain types of businesses and households, such as low‑income households. For example, the CEC’s analysis of the regulation establishing energy efficiency standards for LED light bulbs did not provide information on how the effects of the regulation—including the up‑front costs of more expensive light bulbs, savings on electricity bills from more efficient light bulbs, and reduced pollution associated with electricity generation—would be distributed among households with different levels of income or in different parts of the state.

Limited Guidance and Oversight Contribute to Shortcomings. Limited guidance and oversight likely contribute to many of the analytical issues identified above. DOF and OAL provide guidance on what impacts agencies need to analyze and estimate in order to comply with APA requirements. In addition, for major regulations, the guidance issued by DOF provides some useful, more detailed guidance on analytical methods. However, relative to the federal guidance, it is incomplete. For example, there is little or no guidance for (1) discounting future benefits and costs, (2) identifying a potential range of alternatives to analyze, or (3) characterizing uncertainty.

Oversight of agency analysis is also still limited. Although most regulations are subject to OAL review, OAL largely reviews whether agencies comply with the APA’s procedural and legal requirements. For example, OAL reviews whether the agency has provided the information required in statute and adequately responded to public comments. OAL generally does not have the responsibility, or expertise, to evaluate the quality of the agency’s analysis. DOF provides some additional oversight, but its role is limited in the following ways:

- Review After Rule Is Initially Proposed. DOF is not required to review an updated SRIA if the agency modifies the proposed rule or if new information about the effects of the rule becomes available. For example, ARB made substantial changes to its recent cap‑and‑trade regulation that affects how millions of allowances—worth hundreds of millions of dollars annually—are allocated to businesses. These changes could have significant implications for business competitiveness and GHG emissions, but there is no requirement for DOF to review an updated SRIA.

- Authority to Require Changes. Although DOF issues guidance and comments on the SRIA, it has no legal authority to require agencies to change the analysis, consider additional alternatives, or provide additional analytical justification for the regulatory decision. Also, it does not have the authority to reject or modify proposals that do not meet legislative goals and/or are not cost‑effective.

Certain Analytical Requirements for Major Regulations Offer Limited Value

In some cases, the existing analytical requirements appear to provide limited valuable information that can be used to inform cost‑effective regulatory decisions—which is the main goal of the analysis. We discuss these particular requirements below.

Macroeconomic Analyses Less Useful Than Evaluating Direct Effects. A significant part of the analysis in the SRIA is devoted to estimating effects on such things as statewide employment and economic activity—sometimes known as macroeconomic effects. This focus is largely driven by the APA’s requirement to assess certain adverse economic effects of a regulation, such as effects on jobs and businesses. Before conducting the macroeconomic analysis, agencies estimate the regulation’s direct costs (such as costs to install a new technology) and direct benefits (such as reduced pollution or savings from reduced energy consumption). Most agencies then contract with an outside consultant, which has a model that attempts to estimate how the direct effects would change statewide macroeconomic outcomes. For example, the model might estimate how requiring a businesses to purchase technology to control pollution would affect employment, prices, production, and investment—including for businesses that purchase the technology, businesses that sell the technology, and other businesses that are indirectly affected by these changes.

These macroeconomic analyses have the following limitations that reduce their value for making cost‑effective regulatory decisions:

- Significant Uncertainty. The models used to estimate macroeconomic effects rely on a wide variety of assumptions that are subject to significant uncertainty. For example, the model has to make assumptions about how an increase in costs to a business would affect prices for its product, new investments, employment, and wages for employees. Furthermore, the model has to make assumptions about how those employees will spend their money and how that affects other businesses in the economy. As a result, the findings are more uncertain than a simple assessment of direct costs and benefits.

- Less Transparency. Given the complexity of many macroeconomic models, it is often difficult for the public and stakeholders to evaluate some of the underlying assumptions in the models. As discussed above, these models typically make assumptions about business and household behavior that can have significant effects on the overall results, yet most stakeholders are unable to fully vet these assumptions and understand how they affect the final results.

Based on our review of the discussion of alternatives in the SRIAs, agencies rarely used the results from the macroeconomic analysis to justify the agency’s approach and its decision to reject other options. Instead, agencies largely use the assessment of direct costs or benefits as the basis for their decisions to reject alternative approaches.

In our view, relying on high‑quality assessments of direct effects is a reasonable approach in most cases. Even if policymakers are concerned about macroeconomic outcomes, estimates of direct costs and benefits are often sufficient for understanding the direction and relative scale of overall macroeconomic effects. For example, an energy efficiency regulation that results in large energy savings for very little cost will likely have substantial positive effects on macroeconomic economic conditions. A macroeconomic analysis is likely not necessary to make this basic determination, nor is it needed to determine that alternatives with higher energy savings and/or lower compliance costs will have greater positive effects.

Analysis of Regulations With Limited Feasible Alternatives. Although an analysis of alternatives is typically one of the most important aspects of a regulatory analysis, it is less valuable when few feasible alternatives exist, such as when state or federal law limits agency discretion. As a result, agencies may spend time and resources to develop the SRIA with little added benefit. This appeared to be an issue for a couple of agencies developing SRIAs. For example, the Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development (GO‑Biz) estimated the economic effects of a regulation to implement the California Competes Tax Credit, which was established by the Legislature and provides up to $200 million in annual tax credits for businesses. The law establishing the tax credit also identified 11 criteria that the agency must consider when awarding credits. Therefore, the range of feasible alternatives was limited because many of the key characteristics of the program were already established in law. As a result, the agency’s SRIA largely focused on different administrative approaches to evaluating applications, such as whether GO‑Biz would conduct a more extensive review of applications when they are initially submitted or after first relying on an up‑front screening process. The difference in the overall benefits and costs of the program under these options is unclear, but likely minor.

No Requirement for Retrospective Review

Evaluating the effects of a rule after it has been implemented is known as retrospective review. The primary goal of a retrospective review is to assess whether the regulation had the intended effect. For example, did the rule result in the expected environmental or safety improvements? Was it more or less costly than the agency expected? Such information can improve accountability and oversight. In addition, it encourages agencies to assess the main factors that led to unexpected outcomes. Policymakers can then use the information to decide whether the law or the rule should be eliminated, modified, or expanded. The federal government requires agencies to incorporate plans for conducting a retrospective review as part of rulemaking.

Unlike major state programs that are annually reviewed in the budget process, regulations are not regularly reviewed. In addition, although the APA requires agencies to analyze the potential effects of a regulation before it is adopted, there is no statewide requirement for agencies to conduct retrospective reviews of regulations. As a result, agencies proposing major rules do not include a plan for conducting retrospective reviews, and outcomes are not consistently assessed. For example, agencies do not identify the data and methods that would be used to evaluate the program in the future. Consequently, agencies generally do not incorporate into their regulations specific data collection and reporting requirements needed to evaluate the actual outcomes of their regulations after they are implemented.

Back to the TopLAO Recommendations

Below, we provide recommendations aimed at improving analysis of major regulations in California. The primary goal of these recommendations is to ensure agencies provide information that can be used to support regulatory actions that implement legislative objectives with greater benefits and/or lower costs.

Establish More Robust Guidance and Oversight

We recommend the Legislature establish a more robust system for regulatory guidance and oversight. In our view, this should include requiring an oversight entity to:

- Develop more detailed guidance on best practices for analysis of major regulations, including (1) discounting, (2) identifying and analyzing an adequate range of alternatives, (3) assessing uncertainty, and (4) clearly describing the distribution of benefits and costs across different types of businesses and households. The guidance could largely be based on Circular A‑4.

- Review updated SRIAs when agencies make substantial changes to a rule after it is initially proposed or if agencies receive significant new information about the potential effects of a regulation.

We further recommend that the Legislature consider giving the oversight entity the authority to reject proposed rules that do not include an adequate analysis and/or do not demonstrate cost‑effectiveness.

Determining Appropriate Oversight Entity. The Legislature has different options for which oversight entity should conduct these activities, including DOF or some newly created entity. These options have trade‑offs. For example, locating these activities in DOF would build on existing expertise for reviewing SRIAs. To ensure the regulatory review process at DOF does not focus too heavily on fiscal effects at the expense of broader social effects, the Legislature could consider creating a separate office within DOF that focuses solely on regulatory review similar to OIRA at the federal level. Alternatively, the Legislature could create a new oversight entity that focuses exclusively on reviewing agencies’ analyses of regulatory proposals. For example, it could create a new commission comprised of appointees from the Governor and both houses of the Legislature that operates more independently from the executive branch.

Providing Additional Resources. It is important that the administration have adequate resources to conduct timely and high‑quality analysis. Providing additional guidance and oversight would have some relatively minor administrative costs. For example, doubling DOF’s current staffing of a couple of full‑time people would cost only several hundred thousand dollars annually, but could improve analysis and promote regulations that achieve state policy goals at significantly lower overall cost to businesses and households.

Identify Opportunities to Reduce Requirements That Provide Limited Value

We recommend the Legislature identify opportunities to reduce or eliminate analytical requirements that provide limited value for assessing trade‑offs and making cost‑effective regulatory decisions. The Legislature could eliminate these requirements in statute or give an oversight entity discretion to exempt agencies in specified circumstances. As part of this effort, the Legislature could consider directing the administration to report on the current requirements that provide the least value for making regulatory decisions, relative to the cost of conducting the analysis. For example, an agency could be exempt from modeling statewide macroeconomic effects if it demonstrates that direct costs are relatively small and the analysis is not necessary to adequately compare regulatory alternatives. In addition, the Legislature might want to exempt agencies from certain requirements if they demonstrate that state or federal law limits agency discretion.

Reducing unnecessary requirements would free up agency resources and staff time for other activities. The freed up resources could be used to help the agencies implement regulations more quickly or focus on aspects of regulatory analysis that likely have greater value. For example, agencies could devote more resources to estimating direct costs and benefits of alternatives or conducting retrospective reviews.

Require Agencies to Conduct Retrospective Reviews

We recommend the Legislature consider requiring agencies to plan for retrospective reviews when proposing a major regulation. Agencies would be responsible for carrying out the reviews, although they could have the option to contract with an outside organization. An oversight entity—such as DOF or a newly formed entity, in consultation with outside experts—could be responsible for issuing guidance on best practices for conducting these reviews and overseeing the reviews. Better information about the effects of regulations after they are implemented can improve accountability, oversight, and future regulatory actions.

Agencies would likely have additional costs to conduct the reviews. The amount of costs are unclear and would vary for each regulation depending on its characteristics and the proposed strategy for conducting the retrospective review. However, given the size of overall economic effects of major regulations (over $50 million annually), if these additional resources resulted in even a small increase in regulatory benefits and/or decrease in regulatory costs, the statewide benefits would likely far outweigh state fiscal costs. To ensure retrospective reviews are not too administratively burdensome, the Legislature could allow the oversight entity to exempt an agency from retrospective review requirements under certain conditions, such as if the agency demonstrates that it would be infeasible or too costly to collect adequate data.

Back to the TopConclusion

Senate Bill 617 enhanced guidance and oversight of agency analysis of major regulations in California. However, based on our review of the analyses of major regulations conducted so far, the analyses still do not consistently follow best practices. These limitations make it difficult to understand trade‑offs associated with different regulatory options and determine which options are most cost‑effective. In addition, certain analytical requirements appear to provide limited value and there is no statewide requirement for agencies to conduct retrospective reviews. As a result, we recommend the Legislature direct the administration to establish more robust guidance and oversight of major regulations, identify opportunities to reduce analytical requirements that provide limited value, and require agencies to plan for and conduct retrospective reviews.