LAO Contact

February 24, 2017

The 2017-18 Budget

Analysis of the Department of Developmental Services Budget

- Background

- The Governor’s Budget Proposal

- How Changes to the Community Services Program Are Implemented Will Be Critical For Success

Executive Summary

Increases in Developmental Services Budget Mostly Due to Caseload Growth, Funding to Implement State Minimum Wage Increases. The Governor’s budget proposes $6.9 billion ($4.2 billion General Fund) for Department of Developmental Services (DDS) programs in 2017‑18—a 3.6 percent net increase (5.2 percent General Fund increase) over estimated expenditures in 2016‑17. Increases are primarily due to a growing number of people served in the Community Services Program coupled with funding for service providers to implement state minimum wage increases for minimum wage staff. Spending increases are partially offset by declining costs in the Developmental Center (DC) Program budget (due to declining caseload as residents move into the community).

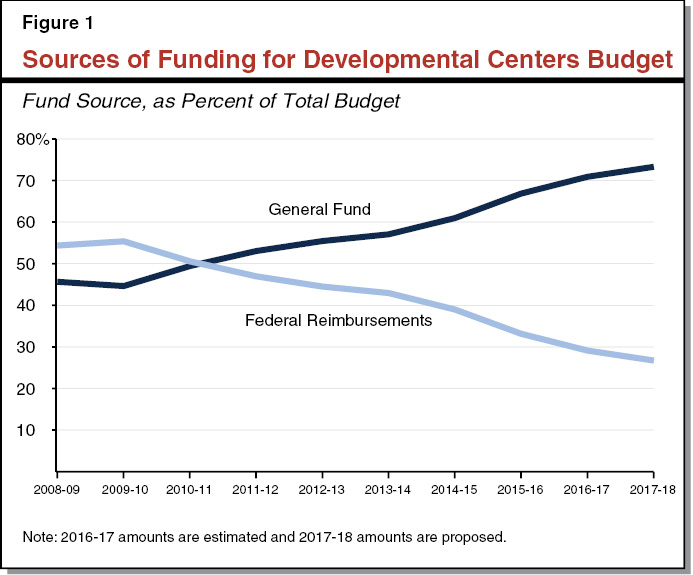

Keeping DC Closures on Track Is of the Utmost Importance Given Increasing Reliance on General Fund and Federal Funding Risks. The state plans to close its three remaining DCs—Sonoma DC by the end of 2018 and Fairview DC and the general treatment area at Porterville DC by the end of 2021. The Governor’s budget proposes $450 million for DCs in 2017‑18, with the state’s General Fund accounting for $330 million (73 percent) of spending. As DC populations decline, there are fewer federally reimbursable services provided, yet base‑level operating costs for the facilities remain, meaning DDS relies more heavily on the General Fund each year. (For example, the General Fund accounted for less than 50 percent of DC spending ten years ago.) In addition, as happened with respect to Sonoma DC, the federal government can revoke funding at any time for the intermediate care facilities at Fairview and Porterville DCs if they are found to be out of compliance with health and safety regulations. Given these funding pressures, it is crucial DDS keeps DC closures on track.

Trailer Bill Changes Intent of Community Placement Plan (CPP) Funding, Raising Issues for the Legislature to Consider. CPP funding is currently used to develop residential and nonresidential services and supports for people moving out of the DCs. A proposed trailer bill would broaden the use of CPP funding, allowing DDS and the Regional Centers to develop resources for consumers who already live in the community. We believe resource development for community residents should be addressed apart from CPP funding decisions, given that CPP funding was intentionally designed by the Legislature to serve those moving from the DCs. Furthermore, the trailer bill proposal was not justified in that it was not accompanied by an assessment of the unmet need that DDS is trying to address. Even if DDS no longer needs all of the CPP funding for DC residents, the Legislature may wish to weigh in on whether excess funding should revert to the General Fund or remain with DDS for other purposes.

DDS Falling Behind in Helping Providers Comply With New Federal Rule, Risking Potential Loss of Significant Federal Funding in Future Years. Of DDS’s nearly $2.7 billion in federal funding in 2017‑18, $2 billion is provided through Home‑ and Community‑Based Services (HCBS) Medicaid waivers. A new federal rule passed in 2014 requires states to modify their HCBS programs to increase quality, consumer choice, and integration of consumers into the community. The state (and its service providers) must comply by March 2019 or it risks potentially losing some or all of its federal waiver funding. We find that DDS has provided relatively little guidance to the state’s tens of thousands of service providers on what compliance means or what programmatic changes they will need to make to reach compliance. Last year, the Legislature appropriated $15 million in ongoing funds to assist providers with compliance efforts and DDS indicates that the hundreds of provider requests (totaling more than $130 million) highlight providers’ lack of understanding about the rule. Given the state’s significant reliance on federal HCBS funding, we recommend DDS report back during budget hearings this spring about the nature of these requests to understand the extent and severity of provider noncompliance and to inform the Legislature regarding what additional resources DDS may need to help facilitate timely compliance.

Rate Study Should Evaluate Rate‑Setting Processes That Adapt to Changes in Policies and Economic Conditions. Last year, the Legislature provided $3 million to DDS for a contractor to conduct a study to examine current provider rate‑setting methods and to provide recommendations to restructure rates. (The current rate‑setting processes are extremely complex and rigid. They have frequently been subject to incremental changes and do not adapt well to changes in policies and economic and market conditions.) The request for proposal (RFP) recently issued by DDS requires the winning bidder to “provide DDS with a documented rate maintenance process,” as part of the study, but does not elaborate on what that means. We understand the RFP cannot be easily changed at this point, but there is a window of opportunity for the Legislature to inform DDS of its preferences to have economic conditions (such as economic recessions), regional market conditions (supply of and demand for provider services), and policy changes (such as minimum wage increases) considered within the RFP’s “rate maintenance” activity. We think that consideration of these factors in the rate study would be of critical value to the Legislature as it considers DDS rate reform.

DDS’s New Program and Fiscal Research Unit Presents an Opportunity for Strategic Decision‑Making. The 2016‑17 budget included $1.2 million in ongoing funds and seven positions for DDS to create a fiscal and program research unit. Although the unit can play a helpful role in responding to legislative and other requests for information, we recommend the Legislature set more specific research goals for the unit that serve to encourage data‑driven decision‑making.

Complicated Rollout of Service Provider Rate Increases May Warrant Relaxed Reporting Requirements. Last year, the Legislature targeted $169.5 million in funding for rate increases to service provider staff who spend at least 75 percent of their time providing direct care to consumers. Although targeting the funding in this way made sense, associated administrative work has been time consuming and some providers may risk forfeiting their rate increases if they do not report back properly by this October. We have recommendations designed to smooth reporting and enforcement related to rate increases.

Background

Overview of the Department of Developmental Services (DDS). Under the Lanterman Developmental Disabilities Services Act of 1969 (known as the Lanterman Act), the state provides individuals who have developmental disabilities with services and supports to meet their needs, preferences, and goals in the least restrictive environment possible. These services and supports are overseen by DDS. The Lanterman Act defines a developmental disability as a “substantial disability” that starts before age 18 and is expected to continue indefinitely. This definition includes cerebral palsy, epilepsy, autism, intellectual disabilities, and other conditions closely related to intellectual disabilities that require similar treatment (such as traumatic brain injury). Unlike most other public human services or health services programs, individuals receiving services through DDS need not meet any income or qualification criteria other than a diagnosis of a developmental disability. The department administers two main programs, briefly described below.

Community Services Program. The DDS currently serves an estimated 303,447 people with developmental disabilities (“consumers” in statutory language) in 2016‑17 through its Community Services Program. Services are coordinated through 21 independent nonprofit agencies called Regional Centers (RCs), which assess eligibility and develop individual program plans (IPPs) for consumers. RCs coordinate residential, health, day program, employment, transportation, and respite services, among others, for consumers. As mandated payer of last resort, RCs only pay for services if a consumer does not have private health insurance or if RCs cannot access so‑called “generic” services (those provided through other state and local government programs, such as Medi‑Cal for qualifying low‑income residents or public education). RCs contract with tens of thousands of vendors around the state to purchase services and supports for consumers. The DDS provides the RCs with a budget for both their administrative operations and the purchase of services (POS) from vendors.

Developmental Centers (DCs) Program. The DDS serves an estimated 847 consumers in 2016‑17 at three state‑run 24‑hour institutions known as DCs—Fairview DC in Orange County, Porterville DC in Tulare County, and Sonoma DC in Sonoma County—as well as one community facility—Canyon Springs in Riverside County, which serves up to 63 people at any time. Porterville includes a General Treatment Area (GTA) and a Secure Treatment Program. (Consumers placed in the secured program at Porterville have either been convicted of a crime or deemed a danger to themselves or others.) In 2015, the administration announced its intentions to close the three remaining DCs—Sonoma DC by the end of 2018 and Fairview DC and Porterville GTA by the end of 2021. Canyon Springs Community Facility and the secured area of Porterville will remain open indefinitely.

For additional general background on DDS and how services and supports are funded and provided, see our report, The 2016‑17 Budget: Analysis of the Department of Developmental Services Budget.

Back to the TopThe Governor’s Budget Proposal

In this section, we provide information about the Governor’s overall budget proposal for DDS, describe budgetary changes to the two main programs—the Community Services Program and the DC Program, provide a status update on federal funding for DCs, and discuss the DDS headquarters budget proposal. We then provide our assessment of the budget package for DDS and analyze one of the proposed trailer bills, which we find raises a number of issues for legislative consideration.

Overall Budget Proposal Largely Reflects Caseload Changes and Funding for Implementation of State Minimum Wage Increases. The Governor’s budget proposes approximately $6.9 billion (all funds) for DDS in 2017‑18, a 3.6 percent net increase over estimated expenditures in 2016‑17. General Fund expenditures account for $4.2 billion of the proposed budget, a net increase of $209 million, or 5.2 percent, over estimated spending in 2016‑17. The net increase in overall spending is primarily due to a growing number of people served in the Community Services Program coupled with funding for service providers to implement state minimum wage increases for minimum wage staff. Spending increases are partially offset by declining costs in the DC Program budget (due to declining caseload as residents move into the community). The Governor’s budget does not include any major new policy proposals or budget initiatives.

Community Services Program Budget Summary

The Community Services Program comprises the vast majority of DDS funding, estimated at $6.4 billion in 2017‑18 ($3.8 billion General Fund), a 5.9 percent net increase over estimated 2016‑17 expenditures. The Community Services Program includes funding for RC operations ($754 million in 2017‑18) and POS ($5.6 billion in 2017‑18) budgets. The proposed Community Services Program budget includes the following adjustments:

- Caseload Growth and Service Utilization Changes. Increase of $317 million ($283 million General Fund) due to caseload growth (of 4.8 percent) and utilization changes compared to the enacted 2016‑17 budget. More than 75 percent of the growth in POS spending has occurred in the categories of community care facilities (CCFs), support services, day programs, in‑home respite, and transportation. A policy change that took effect in July 2016 created a new rate tier for CCFs serving up to four residents (to reflect a current mode of service delivery that encourages smaller homes). This new rate tier results in higher per‑person costs (previously the highest per‑person rate was based on six‑person CCFs).

- State Minimum Wage Increases. Increase of $77 million ($44 million General Fund) to reflect full‑year implementation of a January 1, 2017 state minimum wage increase (to $10.50 per hour) and half‑year implementation of a scheduled January 1, 2018 state minimum wage increase (to $11 per hour).

- One‑Time Community Services Development Funds for Individuals Moving From DCs. In addition to $68 million in ongoing base‑level funding, the Governor’s budget requests about $26 million ($19 million General Fund) in one‑time resources for the Community Placement Plan (CPP). (By comparison, the request in 2016‑17 for supplementary one‑time funding for CPP was for $79 million [$69 million General Fund].) CPP funds are used to aid in the transition of consumers from DCs to the community. RCs request CPP funding to develop new community resources (residential and nonresidential) for these consumers, assess an individual’s needs in moving to the community, and plan for an individual’s community services.

- Decreased RC Operations Funding. Decrease of $200,000 ($100,000 General Fund) due to a new method for estimating RC rent costs. The DDS worked with the Department of General Services to update its methodology to better estimate rent costs by accounting for factors such as fair market values in each location and actual lease costs.

DC Program Budget Summary

The Governor’s budget proposes $450 million all funds ($330 million General Fund) for DCs, a net decrease of 15.1 percent below estimated 2016‑17 expenditures.

- Continuing Declines in Caseload and Staffing. Net decrease of about $81 million ($12 million General Fund) below the enacted 2016‑17 budget, an 18 percent decline, due to reductions in caseload and related staffing adjustments. DDS expects to move 257 residents into the community in 2017‑18, reducing the overall number of DC residents to 490 by the end of 2017‑18. It expects a corresponding net decline in staff positions of nearly 500.

- Closure Activities. Increase of $800,000 ($600,000 General Fund) for archiving historical and clinical records at Fairview and Porterville DCs as well as the relocation of physical property and equipment from Sonoma DC.

- Porterville Water Safety. Increase of $3.7 million in one‑time General Fund spending to install a nitrate removal system for the water supply at Porterville DC.

- New Method for Estimating DC Costs. The DDS implemented a new method for estimating 2017‑18 costs at DCs, now accounting for the base level of staffing required regardless of how many residents live at the DC and basing costs on the number and type of residential units needed at each DC (as opposed to simply the total number of DC residents).

Status Update on Federal Funding for DCs

Several years ago, the California Department of Public Health (DPH)—the state department that has licensing and certification responsibilities over DCs—found the intermediate care facilities for the developmentally disabled (ICF/DDs) at Sonoma, Fairview, and Porterville DCs to be out of compliance with federal certification requirements. In 2013, DDS voluntarily decertified four ICF/DD units at Sonoma DC, but to retain federal funds for the remaining seven units, DDS entered into a settlement agreement (which included a program improvement plan) with the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), DPH, and the California Department of Health Care Services (DHCS). Nevertheless the ICF/DD units at Sonoma were ultimately decertified and became ineligible for federal funding as of July 1, 2016. Despite failing compliance surveys in 2015, Fairview and Porterville DCs have subsequently been more successful in their attempts to implement corrective actions for their ICF/DD units. The CMS, DPH, DHCS, and DDS entered into settlement agreements in July 2016 for Fairview and Porterville GTA DCs that would have terminated funding at the end of 2016. The agreements, however, allowed the certification of these residential units to be extended annually through the end of 2019, and federal funding was recently extended through 2017.

Extension of Certification of Fairview and Porterville GTA ICF/DDs Includes Specific Improvement Activities. The recently extended settlement agreements at Fairview and Porterville GTA DCs included a number of key activities that should keep DDS on track to retain federal funding, including independent monitoring of client protections, health care, and behavioral health and active treatment at each DC. In addition, interdisciplinary teams will monitor the individual transition plans of residents as preparations are made to move them into the community. The DDS notes that its independent monitor conducts mock certification surveys at each DC in an effort to stay ahead of possible deficiencies.

Despite DDS Being Well‑Poised to Retain Federal Funding at DCs, Risk Remains. Although DDS has successfully extended the termination date of Fairview and Porterville ICF/DD certification, CMS reserves the right to revoke certification at any time. If certification is revoked, DDS estimates the monthly loss of funds at $6.7 million in 2016‑17 and $4 million in 2017‑18 ($48 million in annual terms). While DDS is using the same independent monitoring company that it used at Sonoma DC, whose units were decertified, it believes the lessons learned at Sonoma by this monitor can be leveraged at Fairview and Porterville DCs.

Keeping DC Closures on Track Is of the Utmost Importance Given the Increasing Reliance on the General Fund. Ten years ago, California’s General Fund accounted for less than 50 percent of the annual DC budget, whereas it now comprises more than 70 percent (see Figure 1). This reflects that as DC populations decline, there are fewer federally reimbursable services provided, yet base‑level operating costs for the facilities remain. The state is now spending about what it did in 2008‑09 in real dollars despite an estimated decline in caseload of about 70 percent and in the number of state staff of about 50 percent. Beginning in 2020, none of the ICF/DD units at Fairview and Porterville DCs will be eligible for federal funding. It is important to keep closures on track to keep state costs down. The DDS is confident that Sonoma DC will close on time, yet the number of resident transitions in 2016‑17 has not kept pace with initial expectations. Last year, DDS estimated that Sonoma’s resident population would reduce in half over the course of 2016‑17 (from 298 on July 1, 2016 to 156 by June 30, 2017). It now estimates the population will decline just 16 percent (to 249) by June 30, 2017.

Headquarters Budget Proposal

The Governor’s budget proposes $52 million ($35 million General Fund) for headquarters operations expenditures, a 2.2 percent increase over estimated expenditures in 2016‑17. The increase includes $597,000 ($554,000 General Fund) and four positions for oversight of housing developments funded through CPP as well as $398,000 ($317,000 General Fund) and three positions to improve information technology security and privacy infrastructure and practices to comply with state and federal security and privacy laws.

LAO Assessment of Overall Budget Proposal

Caseload Estimates for Community Services Program Seem Reasonable. The community caseload has steadily increased year over year. The Governor’s budget projects RC consumer caseload of slightly more than 317,000 as of January 31, 2018, an increase of 4.6 percent over the estimated caseload as of January 31, 2017. In recent years, the Governor’s budget projections for caseload in the upcoming fiscal year have been relatively close to actual caseload numbers. While we find that the Governor’s overall caseload assumptions appear reasonable, we withhold recommendation at this time pending the release of updated caseload estimates at the May Revision. We will continue to monitor caseload growth trends and recommend adjustments to the Governor’s caseload assumptions, if necessary, following our review of the May Revision.

New Methods for Estimating DC Costs and RC Rent Costs an Improvement. The new method that DDS is using to estimate DC costs appears to provide a more accurate assessment of the particular needs and associated costs at each DC. The new method appears to more precisely estimate the staffing needs—clinical, medical, and administrative—for each of the residential unit types—ICF/DDs, skilled nursing facilities, and acute care facilities. We find that the new method will allow the department to better calibrate staff and facilities costs for a declining DC population. Similarly, the new method DDS is using to estimate RC rent costs appears to be a more accurate reflection of actual costs, rather than a reflection of a potentially outdated rental formula.

Trailer Bill Raises Issues for the Legislature to Consider

Submission of the budget proposal included seven trailer bills. As discussed below, we raise issues for legislative consideration regarding the proposal to broaden the use of CPP funding.

What Is CPP Funding? As mentioned earlier, the state allocates CPP funding to develop community resources (residential and nonresidential) for consumers transitioning from DCs to the community. Among its uses, the funding is used by RCs for the initial costs associated with placing DC residents in the community and for providing the services and supports that would prevent placing someone in an institutional setting. In recent years, CPP funding has been used to develop residential resources for consumers transitioning from DCs, including two new residential models—Enhanced Behavioral Support Homes and Adult Residential Facilities for Persons with Special Health Care Needs—and nonresidential resources, such as day programs and dental services.

What Would the CPP‑Related Trailer Bill Do? Whereas current state law earmarks CPP funding to serve the needs of consumers moving from DCs, the proposed trailer bill would allow DDS and RCs to use CPP funding to develop resources for consumers who already live in the community.

The Trailer Bill Changes the Purpose of CPP Funding. CPP funding is intended to increase resource capacity in the community to serve the needs of former DC residents, as well as to fund these consumers’ transitions into the community. Developing resources for already community‑based residents was not the intended purpose of CPP funding. Broadening the use of CPP funding would result in less available funding for those moving from DCs. This trailer bill proposal was not submitted to the Legislature in conjunction with an assessment of the unmet need DDS is trying to address by broadening the use of CPP funding or details of how the broadened use of CPP funding would be spent. In addition, it does not include an estimate of how much CPP funding would be shifted to these activities.

The Legislature May Wish to Consider Community Resource Development Needs on Their Own Merit. Based on high‑level discussions with DDS, we agree there may be a need for increased resource capacity for consumers living in the community. For example, there are many more consumers with autism than in the past (see page 16 for a more in‑depth discussion of this issue) and consumers are living longer and facing health issues associated with older age (for example, nearly all individuals with down syndrome will develop Alzheimer’s Disease or dementia). In this regard, DDS indicated that resource capacity is needed to adapt to the changing needs of consumers to ensure that there are sufficient providers for the particular types of services being demanded. However, we believe the issue of community service funding requirements should be addressed apart from CPP funding decisions, given that CPP funding was intentionally designed by the Legislature to serve those moving from DCs. Even in the event DDS no longer needs all of the CPP funding for DC residents because most projects are already underway, the Legislature may wish to weigh in on whether that funding should revert to the General Fund or remain with DDS for other purposes. When assessing the issue of community service funding requirements on their own merit, the Legislature could also evaluate alternative funding mechanisms for developing community resources. As discussed further later, the Legislature could consider requiring DDS to conduct an assessment of where community services currently fall short before requesting additional funding to address these gaps in service coverage.

Back to the TopHow Changes to the Community Services Program Are Implemented Will Be Critical For Success

The field of developmental services is undergoing several large shifts in both policy and practice, the implementation of which have near‑ and long‑term implications for the state’s system of developmental services. How DDS implements these changes will affect funding streams, quality of service provided, and consumer outcomes. Below, we describe the general nature of the changes, detail the relevant state and federal policies and their implications for the future developmental services program in the state, and discuss issues for the Legislature to consider as DDS implements these changes.

State and Federal Policy Supports a “Person‑Centered” Approach

A person‑centered approach to serving people with developmental disabilities is a philosophy, practice, and policy.

Philosophically, the Person‑Centered Approach Puts the Person First. The person‑centered approach means viewing someone as a person first, rather than defining that person by his or her disability. It means that rather than limiting someone’s choices based on what is available within the developmental services network, the person is allowed to express his or her own hopes and preferences.

In Practice, Person‑Centered Planning Identifies Consumers’ Preferences. In California, person‑centered planning is the process used to develop a consumer’s IPP. The process involves ongoing meetings and discussions among the individual, his or her family (if appropriate), other relevant people (such as RC clinical staff or caregivers), and the individual’s RC service coordinator. Through this process, the IPP is developed to identify and understand the individual’s goals and preferences and to select the services and supports (such as residential and employment) needed to advance these goals and facilitate daily living.

The Person‑Centered Approach Drives Policy. The person‑centered approach is at the heart of current state and federal developmental services policy. The state of California codified an individualized person‑focused IPP process and the right of individuals with developmental disabilities to make choices about their own lives through 1992 amendments to the Lanterman Act. Rules passed by CMS make federal funding to the states contingent on states using a person‑centered approach to determine preferred and needed services and supports. Although California has been using a person‑centered approach since the 1990s, DDS must implement recently enacted federal and state regulations and policies that further advance person‑centered objectives.

New Federal Rule With Major Programmatic Implications Requires Compliance by March 2019. California receives federal funding for approximately 130,000 consumers through Home‑ and Community‑Based Services (HCBS) waivers. HCBS waivers provide Medicaid funding for Medicaid‑eligible individuals to receive long‑term care services and supports in home‑ and community‑based settings, rather than in institutions. (Beneficiaries include persons with developmental disabilities as well as other people at risk of institutionalization, such as older adults and people with long‑term illnesses or physical disabilities.) Waiver funding requires the state to equally match federal contributions, which it does through the General Fund. As a condition of receiving ongoing waiver funding, states have until March 2019 to be in compliance with new HCBS waiver conditions (called the “final rule”) passed by CMS in 2014.

HCBS Final Rule Focuses on Community Integration and Consumer Choice. According to CMS, the final rule “creates a more outcome‑oriented definition of home‑ and community‑based settings, rather than one based solely on a setting’s location, geography, or physical characteristics.” It defines, and requires states to use, a person‑centered planning process and it provides requirements for home‑ and community‑based settings to maximize consumer independence and integration into the community. Examples of new residential requirements include requirements that consumers must be able to come and go freely, have visitors whenever they would like, have their own bedroom, and be able to lock their bedroom door from the inside. The final rule requires day program and employment settings to be integrated with, and for consumers to have access to, the greater community. States must submit a “Statewide Transition Plan (STP),” which provides details about how they plan to meet the requirements of the new rule. DHCS submitted California’s revised transition plan in November 2016.

DC Closure Policy Was in Part a Fiscal Decision . . . The state began providing DC services to people with developmental disabilities in the late 1800s and over time has operated as many as 11 DCs, including programs within state hospitals. After passage of the Lanterman Act in 1969, DC populations began to decline as more consumers received services in the community. In 2012, the Legislature issued a moratorium on new admissions to DCs, and in 2015, the decision was made to close the remaining DCs. DDS submitted the last of the remaining closure plans (for Fairview DC and Porterville GTA) to the Legislature in April 2016.

The decision to close the DCs was in part a cost‑savings measure (as were federal HCBS rules to deinstitutionalize people with developmental disabilities). At the time the decision was made to close the remaining DCs, the average annual cost to serve a DC resident was about $500,000; by 2017‑18, the cost will be closer to $700,000. (As the population declines, the average annual per person cost will continue to rise because the state still has to maintain the buildings and land, and provide a minimum level of staffing). By comparison, it is generally less expensive to serve a resident living in the community, although the cost per person varies greatly depending on a person’s severity of disability, residential setting, and mix of services.

. . . But Also a Promotion of the Person‑Centered Approach. In addition to the compelling financial reasons for closing DCs, the state has also been moving toward a more integrated and community‑based system for people with developmental disabilities for more than two decades. Transitioning residents out of DCs and into the broader community provides former DC consumers with greater access to community life and is in line with the state’s emphasis on a person‑centered approach.

Competitive Integrated Employment (CIE) Promotes Integration and Pay at the Going Wage . . . At both the state and federal levels, policy has shifted when it comes to the employment of individuals with developmental disabilities, again to a more integrated and person‑centered approach. In 2013, the Legislature enacted Chapter 667 of 2013 (AB 1041, Chesbro), to implement an “employment first” policy, which provides that CIE will be the highest priority for working age people with developmental disabilities, regardless of the severity of their disability. In 2014, Congress passed the Workforce Innovation and Opportunities Act (WIOA), which promotes CIE and increased training and supports (particularly for those age 24 and younger), and generally prohibits employers from paying subminimum wages to employees with developmental disabilities. The WIOA also provided a definition of CIE: full‑ or part‑time work compensated at either the going wage for that particular position or the minimum wage—whichever is higher—and in which the employee interacts with individuals who do not have disabilities and has opportunities for advancement. In collaboration with the California Departments of Education and Rehabilitation, DDS recently released a draft employment blueprint. Once finalized, the blueprint will provide a road map for increasing CIE over a five‑year period so as to achieve full compliance with WIOA requirements.

. . . And a Paradigm Shift Away From Previous Activities. Seeking mainstream employment for people with developmental disabilities is a shift away from the types of programs and work activities that are still the mainstay. For example, more than 50,000 consumers currently participate in day programs, which provide social‑skills and self‑care training to groups of consumers in a set location or out in the community. These are not paid work programs but rather daytime activity programs. Day program expenditures currently comprise one‑fifth of POS spending. Another mainstay is work activity programs, which involve large “sheltered workshops” and typically pay participants subminimum wage. About 1 percent of POS spending is for work activity programs, which currently serve about 10,000 consumers. Meanwhile, individual and group supported employment programs (which make up about 2 percent of POS spending) provide on‑the‑job support and coaching to more than 10,000 consumer employees, many of whom earn at least minimum wage. In the past, consumers who wanted to work in the community often lacked a variety of jobs from which to choose. One goal of employment first is to provide more job options as well as the training and education required for those jobs.

The Current Rate of Employment Is Unclear; Proposed Trailer Bill Will Facilitate Data Collection. It is currently difficult to know exactly how many people with developmental disabilities in California have paid work—and at what pay level—because an individual’s work may not be part of an employment program or because an individual may not earn enough to pay income taxes. Proposed trailer bill language would require RCs to report on employment data in their performance contracts with DDS. DDS has said it will work with RCs to address some of the data gathering challenges.

Self Determination Program (SDP) Will Give More Control to Consumers. Another state policy—Chapter 683 of 2013 (SB 468, Emmerson)—that will promote consumer choice and independence is the creation of the SDP. SDP will give interested consumers greater choice in selecting the services and supports they prefer. Although the current IPP process uses a person‑centered approach, SDP will go a step further. It will allow consumers to control how their budget is spent on services and supports identified in their IPP, select their own service providers (including ones that are not “vendored” with the RC), and decide whether they would like to work with their RC service coordinator or an independent facilitator. Participating consumers will still be required to design an IPP and they will be required to work with a financial management service to manage their budget (currently, more than 8,000 consumers already work with a financial management service at an average annual cost of $460).

SDP Contingent on Federal Waiver Funding. Implementation of SDP depends on California securing federal funding through a new HCBS waiver. The state’s waiver application proposes phasing in SDP over three years for up to 2,500 randomly selected consumers. At the end of the phase‑in period, DDS will offer SDP to any interested RC consumer. DDS submitted its waiver application in 2014 and revised application in 2015, and hopes to finalize the terms with CMS in the coming months. DDS maintains it is ready to roll out SDP upon approval of the waiver.

Funding Pressures in the Community Services Program

This section first notes the sources of fiscal pressure (at least in the near term) resulting from recent policy changes described above. These include the possible loss of federal funding if the HCBS compliance deadline is missed, the costs associated with HCBS compliance, the funding risks and costs associated with federally required service coordinator‑to‑consumer caseload ratios, and the need to develop community‑based crisis services as DCs close. We then go on to describe financial pressures associated with other types of policy changes (such as state minimum wage increases) and with population and demographic changes in the developmental services system at‑large (including growth in caseload, growth in the number of autism cases, increasing diversity, and longer life expectancy).

Resulting Funding Pressures From Recent Policy Changes

New state and federal policies that promote consumer choice and community integration could ultimately save the state money. For example, serving consumers in the community is far less expensive than serving them in institutions (as described earlier). Consumers who find CIE may need fewer government‑funded benefits. Evaluations of SDPs in other states have shown that they can save money. Still, there are funding pressures associated with implementing these new policies, as described below.

Major Federal HCBS Funding at Risk. Federal reimbursements for developmental services currently provide about 40 percent of California’s total DDS budget—$2.7 billion in 2017‑18. Federal reimbursements from the Medicaid program ($2.4 billion) provide the bulk of this funding and of that amount, about $2 billion (or 30 percent of the entire DDS budget) is provided through HCBS waivers. Nearly 60 percent of consumers do not receive HCBS waiver funding, yet all service providers must be in compliance with the final rule because they may serve someone who does receive waiver HCBS funding. According to the STP the state submitted to CMS this past September (which CMS has not yet approved), there will be a three‑part process to assess whether service providers comply with the final rule. First, DDS will work with DHCS to send self‑surveys to all service providers to gauge how well the providers’ current operations align with the final rule. Second, DDS will conduct interviews with consumers to gather their opinions about the services they receive. Lastly, DDS will conduct on‑site assessments of a sample of service providers. DDS will give the assessment results to providers so they can ameliorate any problems.

It remains unclear how stringently CMS will enforce the deadline and compliance requirements and what the consequences will be if full compliance is not reached by March 2019. For anything less than full compliance, the state risks losing some or all of its federal HCBS waiver funding.

State Funding to Assist HCBS Compliance Efforts Among Service Providers Is Another Funding Pressure. In the 2016‑17 Budget Act, the Legislature appropriated $15 million in ongoing funding for DDS to allocate to service providers who demonstrated they needed assistance to comply with the HCBS final rule. The legislation requires RCs to report annually on the number of providers receiving funding for these compliance efforts. According to DDS, last October, more than 900 service providers (less than 5 percent of the estimated number of providers) submitted proposals for more than $130 million in funding requests. The variety of requests appear to highlight a lack of understanding about the final rule, which could be a result of the limited guidance provided thus far by the state. The funding pressure on the system stems both from the risk of losing federal waiver funding (as discussed above) and from the unknown cost to the state to provide financial assistance to service providers to bring them into compliance.

Required Improvements to Service Coordinator‑to‑Consumer Caseload Ratios Create Funding Pressures. Current state law, as well as the terms of the current HCBS waiver, require RCs to have specified average service coordinator‑to‑consumer ratios depending on certain consumer characteristics. For example, federal HCBS rules require RCs to maintain an average service coordinator‑to‑consumer ratio of 1‑to‑62 for consumers receiving services through the HCBS waiver. State law further requires RCs to maintain an average ratio of 1‑to‑45 for consumers who have moved from a DC within the previous 12 months, 1‑to‑62 for consumers age three and younger, and 1‑to‑66 for all other consumers. The RCs have had longstanding challenges with maintaining these required caseload ratios, citing significant funding issues that may relate to the department’s overall methodology for funding RC operations. The 2016‑17 budget included $17 million (all funds) to support an estimated 200 additional RC service coordinator positions with the goal of improving RC coordinator‑to‑consumer caseload ratios. In addition, statute requires RCs to report annually to DDS on the number of staff hired with these additional funds as well as on RC’s effectiveness in reducing average caseload ratios. DDS indicated that RCs will provide information about hiring and an update on coordinator‑to‑consumer ratios in early March; DDS will provide an overall update in April or May.

Funding pressures stem from two main sources with regards to coordinator‑to‑consumer caseloads. First, there is an HCBS compliance issue and the risk of losing some amount of federal funding. Second, there is the cost associated with hiring additional coordinators, which, as noted above, special session legislation attempted to address last year. Until DDS reports back on this information, it is unknown what more may be required to improve caseload ratios.

Crisis Services and Safety Net Resources Will Be Lost With DC Closures, Creating Funding Pressures to Replace Them. DCs currently provide a safety net for consumers who are in crisis or who exhibit significant behavioral challenges. Not only are the DCs each licensed as general acute care hospitals with onsite medical staff, but Sonoma and Fairview DCs each house an acute crisis facility that can serve up to five consumers in crisis at a time. The DDS indicated that these crisis facilities are nearly always full and the average length of stay is about 315 days. Once the DCs are fully closed, the system can no longer fall back on DCs as a last resort for the provision of crisis services.

Crisis and Safety Net Resources Must Be Ready Before Final DC Closures. The system has responded in several ways to the future loss of crisis and safety net services. As of January 2017, RCs were in the process of developing eight community crisis homes to serve residents moving out of Sonoma and Porterville DCs. Community crisis homes are meant to be temporary residences for the consumer while he or she stabilizes. Currently, no community crisis homes have been opened. Another option that is under development to serve as a safety net for consumers with especially challenging behaviors is the Enhanced Behavioral Support Home (EBSH). An EBSH is meant for consumers who require nonmedical 24‑hour care and advanced behavioral support. For up to six of these homes (more than 20 are currently under development for those moving from DCs), delayed egress devices (which provide a short delay on exit doors to allow staff to quickly assess the situation) in combination with a secured perimeter may be added. Homes with delayed egress and secured perimeters are meant to provide temporary (up to 18 months) stabilization for consumers in need of intensive intervention and who may be at risk of harming themselves or others. The funding pressure in this context stems from the need to develop crises services for consumers in need and the need to have these resources in place by the time the DCs are fully closed.

Other Funding Pressures Also Exist in the Developmental Services System At‑Large

Raising the State Minimum Wage Increases Costs for Service Providers and State. There is precedent for the Legislature to appropriate funding to cover service providers’ increased staffing costs due to increases in the state’s minimum wage. For example, in the past decade, the state budget provided increases for affected providers in 2006‑07, 2007‑08, 2014‑15, 2015‑16, and 2016‑17. The Governor’s budget proposes about $77 million ($44 million General Fund) for this purpose in 2017‑18 to account for the increases that took effect in January 2017 and the one that is scheduled to take effect in January 2018 as the minimum wage continues its scheduled step‑by‑step progression to $15 by 2022. The funding increases do not account for “wage compression” resulting from the implementation of a minimum wage increase. Wage compression is the concept that as the wages of the lowest paid workers increase, the gap between their wages and the wages of their managers or higher‑ups tightens or closes altogether. Employers then face pressure to increase the wages of those employees as well. This issue can ultimately lead to pressure on the state to raise provider rates to mitigate the impacts of wage compression.

Local Minimum Wage Increases May Trigger Provider Requests for More Funding. The Legislature has not traditionally appropriated additional funding to cover service providers’ increased staffing costs due to increases in local minimum wages. Currently, more than 20 cities in California have a minimum wage that is higher than the state’s. The mechanism by which a service provider may request a rate increase from DDS to cover its higher staffing costs due to a factor such as a local minimum wage increase is to submit a health and safety (H&S) waiver through the vendoring RC for each consumer served by a provider. On a consumer‑by‑consumer basis, the provider must demonstrate that the health or safety of the consumer is at risk without the requested funding. While DDS sometimes grants approval for H&S waivers to account for local minimum wages, the application process is administratively cumbersome for the vendors, RCs, and DDS.

Other Labor Laws Have Also Increased Service Provider Costs. Recent changes to other labor laws have also created additional costs in the system. The state provided a 5.82 percent rate increase, effective December 1, 2015, for certain services to implement new federal regulations requiring overtime pay for home care workers. The 2016‑17 enacted budget provided $18.4 million ($9.9 million General Fund) to cover these costs.

Rapidly Rising Caseloads—With a Rising Share of Consumers With Autism—Increase Costs . . . The overall growth in the number of consumers eligible to receive developmental services has outpaced population growth in California. Annual caseload growth has averaged about 4.6 percent since 2015, when broadened eligibility criteria were reinstated for infants and toddlers under three years of age. (Eligibility for this age group was tightened between 2009 and 2015 as a cost‑savings measure.) Average annual growth over the past ten years has been 3.7 percent. Meanwhile, the state’s population has increased at an average rate of 0.8 percent.

The underlying reasons for such significant caseload growth are not fully understood, but are likely to include such high‑level factors as an aging RC population and an increase in the autism population served by DDS. About 35 percent of all consumers today are diagnosed with autism, about three and a half times the share in 2000. The rapidly increasing share of consumers with autism exerts a cost pressure on the developmental services system because autism is the most expensive developmental disability to treat on average, according to DDS. The vast majority of consumers with autism are between the ages of 3 and 21. Consumers under the age of 22 are eligible for many government services, such as public education and most live with their parents. As this large group of children begins to reach adulthood, DDS will have to cover a much larger share of the cost to serve them.

. . . Other Demographic Shifts Likely Increase Costs. Other demographic changes among consumers are also likely to increase costs. For example, for about one‑quarter of consumers, English is not their primary spoken language. Although the shares of English and non‑English speakers have increased at similar rates in recent years, the growth in the number of non‑English speakers requires RC and service provider staff to accommodate them. Another demographic shift is the increasing life expectancy of people with developmental disabilities. As consumers live longer, they will need care longer, more intensive health care when they are older, and their parental caregivers may be unable to care for them as the parents themselves age or pass away.

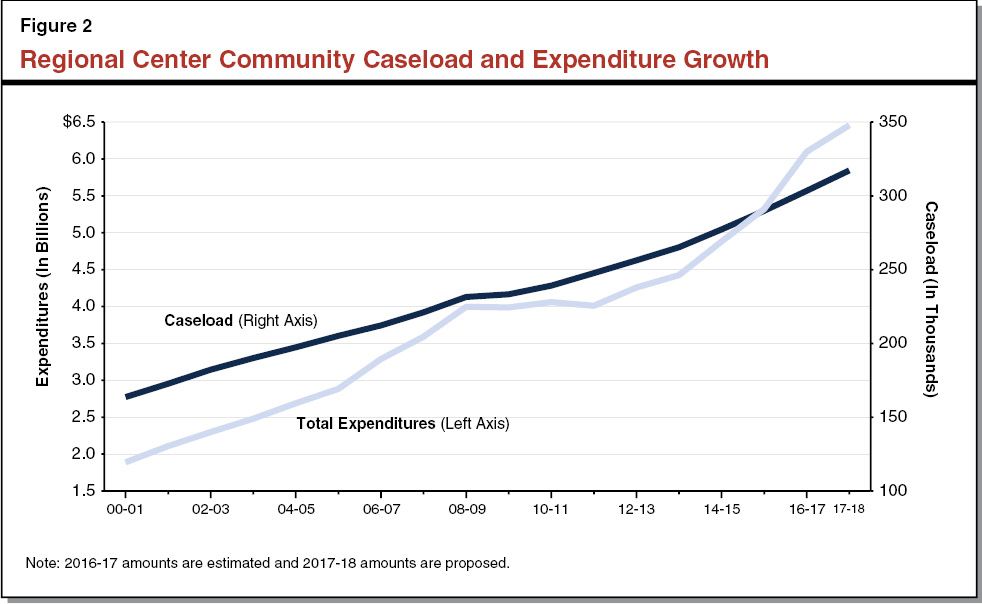

Figure 2 shows the rapid rise in RC caseload since 2000‑01 along with corresponding DDS expenditures (all funds). Although expenditure growth stalled during the Great Recession, funding increases that were part of last year’s special session legislation and budget act have accelerated growth.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

Below, we identify several issues for legislative consideration and offer a number of recommendations designed to smooth the implementation of the recent policy changes and ensure effective legislative oversight of such implementation.

Service Providers Could Miss HCBS Compliance Deadline

Final Rule Issued in 2014, Yet the State Has Been Slow in its Efforts to Facilitate Compliance. Although DDS must coordinate HCBS compliance efforts with DHCS, we have concerns that too little guidance has been provided thus far to service providers to ensure their compliance by March 2019. The primary activities underway thus far include convening of an advisory group to guide the transition process; posting informational pieces, fact sheets, and frequently asked questions online; providing a copy of the STP online; and notifying RCs of the $15 million in funding provided by the Legislature for compliance activities (and associated application rules).

We understand that DHCS is still awaiting final approval of the STP from CMS to begin official provider assessments, but our concern is that time is running out for the actions necessary for providers to reach compliance by March 2019. The STP proposes conducting provider self‑surveys for the better part of 2017, and onsite assessments from the first quarter of 2017 through the third quarter of 2018. This leaves only a short window for remediation activities identified as necessary from the self‑surveys and onsite assessments—perhaps as little as a few months for some providers. However, if DDS does not begin these activities until CMS approves the STP, this further compresses the short window to achieve compliance with the final rule. It is concerning that DHCS only just submitted the state’s revised STP (on November 23, 2016), leaving at most two years for much of the serious compliance work (and that assumes CMS approves the plan quickly).

We recognize that DDS has made efforts in this area, for example, increasing residential capacity that conforms to new requirements, convening taskforces and workgroups, releasing an employment blueprint in coordination with the Departments of Rehabilitation and Education, and allowing providers to apply for funding to support compliance efforts. Our concern remains, however, whether the tens of thousands of service providers around the state will have made the necessary programmatic and facility changes to come into compliance by 2019, especially since so little is known about the extent of noncompliance with the final rule.

LAO Recommendation—Direct DDS to Report at Budget Hearings on How Compliance Funds Were Allocated. As noted earlier, last year the Legislature appropriated $15 million in ongoing funding for DDS to allocate to service providers for compliance activities related to the final rule. Currently, statute only requires that RCs report on the number of service providers that received funding for this purpose. Given the sheer volume of requests (more than 900) and total amount of requests (more than $130 million) received last fall for compliance funding, the Legislature could direct DDS to report at budget hearings with details on what it gleaned from the funding requests. The report at budget hearings could include information on the nature of the funding requests, whether they identified any serious compliance issues, what service providers proposed to do, whether the proposals taken together highlight a need for educational efforts about the final rule, and how much additional funding DDS estimates service providers will need for compliance efforts based on the proposals submitted. Although the self‑surveys and onsite assessments will also be seeking some of the same information, DDS could use the information it already has to gauge the gravity of compliance issues and inform the Legislature of how it intends to remediate these problems ahead of the March 2019 deadline. In its report, DDS could also inform the Legislature of its priorities for allocating the appropriated compliance funding and generally how it decides which funding requests to approve.

Clarity Needed on “Rate Maintenance Process” in DDS Rate Study

Current Rate‑Setting Process Is Very Complicated. Provider rate‑setting methodologies vary significantly depending on the type of service and provider, and have frequently been subject to incremental changes, making the overall rate‑setting process highly complex. The vast majority of POS rates are set by DDS or negotiated between the provider and RC. Some rates, however, are established by DHCS through the Medi‑Cal program, set at what is charged to the general public and referred to as “usual and customary” rates, or set using other methodologies.

For rates negotiated between RCs and vendors, budget solutions taken by the Legislature during the recent recession froze rates and established a median rate process for new vendors (RCs assign new vendors the lower of the RC median rate or the statewide median rate for that service). Legislation passed in 2011 recalculated the medians, which meant that most median rates were lowered. These policies remain in effect. One consequence has been that new vendors in high‑cost areas are often assigned the statewide median rate (which can be a disincentive to enter the market). In addition, it means there are large inequities in the rates paid to vendors providing the same service that entered the system before and after the rate freeze.

Similarly, the current rate‑setting processes have been complicated by policy changes. For example, in response to minimum wage increases, the state has increased rates for providers with minimum‑wage employees, but has not accounted for the resulting wage compression. As another example, the current mode for residential facilities is to have four residents (rather than six), but for a long time (up until last year), rates were unable to account for this shift in service delivery.

Special Session Legislation Required a Rate Study. DDS received $3 million last year for a contractor to conduct a service provider rate study and provide recommendations about rate setting. The rate study and recommendations to address some of these problems are due to the Legislature by March 1, 2019. Statute stipulates that the study should provide an assessment of the current methods for setting rates, including whether they provide an adequate supply of vendors; a comparison of the fiscal effects of alternative rate‑setting methods; and how vendor rates relate to consumer outcomes. It also requires an evaluation of the current number and types of service codes and recommendations for possible restructuring of service codes. The request for proposal (RFP) for the rate study was just released on February 9, 2017.

RFP for the Rate Study Includes Requirement That Contractor Provide a Rate Maintenance Process. The contractor awarded the rate study project is required to “provide DDS with a documented rate maintenance process, and the multiyear fiscal impact.” We assume that “rate maintenance” refers to the process of making rate adjustments over time. (For example, in other areas of government, some benefits or rates for services are automatically adjusted based on changes in the Consumer Price Index.) It is not stated explicitly whether the rate maintenance activity in the RFP includes consideration of how the rate‑setting process should account for, and adapt to, changing economic conditions and policy changes that are outside of DDS’s control. Much of the system’s current complexity is due to these factors. We think that consideration of these factors in the rate study would be of critical value in informing the Legislature as it considers DDS rate reform.

LAO Recommendation—Inform DDS of Legislative Preference for Including Consideration of Economic and Policy Changes in the Rate Maintenance Process. We recommend the Legislature inform DDS of its preference to have the role of economic and policy changes considered within the rate maintenance activity identified in the RFP. Rate maintenance is currently not defined in the RFP. The Legislature could request that DDS work with prospective bidders about its meaning. For example, rate maintenance could include:

- Options for how the Legislature and DDS could reduce costs in recessionary times, while minimizing adverse impacts on consumer outcomes. This could include recommendations for making targeted reductions rather than across‑the‑board cuts or rate freezes.

- Options for how the Legislature could either restore funding or return to a regular rate maintenance schedule after cost‑savings measures have been taken.

- Options for how the Legislature, DDS, and RCs could make ongoing rate adjustments based on regional market conditions, including how the supply of services by providers meets the demand for services by consumers.

- Options for how the Legislature and DDS could implement rate changes associated with minimum wage increases (and other labor laws), including how to measure the number of affected vendors and employees, as well as how to address wage compression.

- Options for how the Legislature and DDS could handle policy changes, such as changes in authorized modes of service delivery, that have a direct impact on rates, including recommendations for incorporating flexibility in the rate structure.

We acknowledge that DDS already posted its RFP and that prospective bidders will be submitting their proposals by early April. In the interim, DDS will be answering questions from, and providing further guidance to, prospective bidders. In light of these timing constraints, we recommend that, during budget hearings prior to early April, the Legislature make the department aware of its preference to include economic and policy considerations in the rate maintenance activity and see whether DDS concurs that these factors should be considered. By making DDS aware of its preferences for what the rate study should encompass, the Legislature would help inform the guidance provided to prospective bidders by DDS during the RFP process and inform DDS’s selection process for the winning bid.

New Research and Fiscal Unit Presents an Opportunity for Strategic Decision‑Making

First Year Focused on Hiring, Restructuring. The 2016‑17 budget included $1.2 million ($930,000 General Fund) and seven positions for DDS to create a fiscal and program research unit. In its budget change proposal last year, DDS noted that it receives numerous requests for data and information, but that unlike other departments of its size, had no staff dedicated to research and analysis to respond to these requests. Since establishing the unit, DDS has to date hired a PhD‑level unit manager and filled two other positions. DDS reports that it has consolidated some of its administration, data extraction, and audit functions within the new unit, and that it intends the new unit to respond to requests and respond more quickly, archive requests and responses, inform decisions related to the annual January and May budget estimates, fulfill statutory reporting requirements, and examine historical costs.

New Unit Can Also Play an Important Role in Policy Decisions and DDS Oversight of RCs. As service delivery continues to move toward consumer choice and independence, we believe this unit could play a critical role, helping the department and the Legislature make data‑driven policy and budget decisions. In addition, RCs are currently required to report many types of information to DDS about their POS and operations budgets among other things. The new research unit could use this information to conduct analyses of RC and service provider performance and evaluations of consumer outcomes (including labor market outcomes and consumer satisfaction), in an effort to strengthen DDS oversight of RCs.

LAO Recommendation—Legislature Could Set More Specific Goals for the Research Unit. To help ensure the research unit does not become overly focused on, and get bogged down in responding to requests for information—and without being overly prescriptive—the Legislature could weigh in on the overall goals and projects for the new fiscal and program research unit, particularly as they concern the person‑centered approach, compliance with federal rules, and rate reform. Such goals and projects could include:

- Assessment of Gaps in Service and Provider Capacity. We noted earlier in the discussion of CPP funding that the proposed trailer bill did not include information about what community resources are hardest to find for community‑based consumers. Whether or not the Legislature approves the trailer bill, it could consider requiring DDS to conduct an assessment of these service gaps. Particularly if the Legislature considers providing ongoing funding for community resource development (separate from CPP funding), this assessment would enable to the Legislature and department to make strategic decisions about funding and projects, respectively.

- Identify the Causes of Disparities in POS Funding. RCs and DDS currently provide data on disparities in POS authorization and access in response to a statutory requirement. The data have identified significant disparities among racial/ethnic groups in terms of access to, and amount of, POS spending. Last year, the Legislature provided $11 million in funding to try to reduce these disparities, which is being allocated to RCs based on proposals the RCs submitted to DDS. A study to better understand the root causes of POS disparities could inform future decisions about steps RCs can take to reduce disparities and about which future RC proposals to fund. It could also better position the RCs to prevent future disparities.

- Identify Alternatives to RC Core Staffing Formula. The rate study that will be completed by 2019 is one piece of finance reform in the developmental services system. Another significant component is the way in which RCs are reimbursed for their operations costs. Currently, estimated RC operations costs are based on a core staffing formula, which is outdated in terms of both staff salaries and position types. The fiscal and program research unit could conduct an analysis of current staffing and salary challenges, research alternative methods for estimating staffing, and provide recommendations to the Legislature about how to reform the current budgeting methodology.

Implementation Challenges of 2016 Rate Increases

Targeting Increases to Direct Care Staff Made Sense . . . When weighing its options last year during the special legislative session, it made sense that the Legislature wanted service provider rate increases to go to staff providing direct care for consumers (as opposed to administrative staff). Targeting $169.5 million in funding to staff spending at least 75 percent of their time to provide direct consumer care reflected the state’s goals for achieving positive consumer outcomes and focusing efforts to improve and honor consumer choice. The rate increase affected service providers that have rates determined by DDS or through negotiations with the vendoring RC, but did not affect rates set by DHCS or the Department of Social Services.

. . . But the Rollout Has Been Complicated. The targeted increase requires a significant amount of administrative work on the part of DDS, RCs, and service providers. Statute required DDS to complete a provider survey (in coordination with RCs) with a random sample of service providers to determine how to allocate the fixed amount of the appropriation. It also requires DDS to conduct a survey by October 1, 2017 to find out how providers used the rate increase (including number of employees affected, the percentage of time that these employees spend on direct care, administrative costs, and any other information requested by DDS). Every provider who received the rate increase must complete the survey by October 1 or risk losing funding. DDS is not requiring new providers that entered the system after June 30, 2016 to complete the survey. DDS is also required to report on implementation of the rate increases in its 2017‑18 May Revision fiscal estimate. Based on discussions with DDS and provider advocates, it appears that completion of the mandated vendor survey will be administratively burdensome. DDS noted that it was not easy getting providers to respond to the initial survey that they used to determine how to allocate the funding. It also appears that many providers are unaware of the reporting requirement and that they will lose the increased funding if they do not respond. It may also be difficult for some of the smaller vendors to collect the required information. DDS intends to begin outreach efforts within the next month.

LAO Recommendation—Conduct Statutory Clean‑Up to Ease Reporting and Enforcement. The extent of the administrative burdens to allocate the funding for the 2016 rate increases was likely not known to the Legislature when the special session legislation including the rate increases was enacted. We note that the Legislature’s objective of having the rate increases not going to support largely administrative costs could be met to some degree on the natural given that current law places a 15 percent administrative cap for providers with rates set through negotiations with the RCs. (This cap affects providers that account for roughly half of the relevant spending.)

To smooth reporting and enforcement related to the 2016 rate increases, the Legislature might consider amending the provisions of the special session legislation. Specifically, the Legislature could consider relaxing the rule that providers forfeit the increase if they fail to report how they implemented the increase. It could also consider removing the survey reporting requirement altogether, or extending its October 1, 2017 deadline. One benefit of this approach would be to free up DDS, RC, and service provider administrative resources that could otherwise be spent on activities that work toward 2019 compliance with the HCBS waiver regulations.

Finally, it may be worth using this experience regarding the administrative efforts required to implement, report on, and enforce a targeted rate increase to inform future, more administratively streamlined rate increases (at least until rate reform is addressed at a more fundamental level). The administrative costs—in terms of DDS, RC, and provider time to implement a complex increase (no matter how well intentioned)—may outweigh the policy benefit of targeting the rate increases. For example, a simple percentage increase may be more efficient, especially given the caps on administrative costs already in place for many service provider categories.