LAO Contacts

March 8, 2017

Do Communities Adequately Plan for Housing?

- How Local Governments Plan For Housing

- Planning for New Housing Often Falls Short

- How Should the State Respond?

Executive Summary

California’s cities and counties make most decisions about when, where, and to what extent housing will be built. For decades, many California communities—particularly coastal communities—have used this control to limit home building. As a result, too little housing has been built to accommodate all those who wish to live here. This lack of home building has driven a rapid rise in housing costs.

Two important components of communities’ decisions about housing can limit home building. First, in crafting their long‑term land use plans and implementing these plans through zoning, cities and counties can provide inadequate opportunities for new housing to be built. Second, cities and counties can create onerous processes for the approval of new housing developments. We discussed this latter issue last May in Considering Changes to Streamline Local Housing Approvals in which we looked at a proposal from the Governor to streamline approvals. We concurred with the Governor that state actions should be taken to limit local approval requirements faced by proposed housing developments that are consistent with local land use rules. And we suggested these changes apply to all types of housing development.

In Considering Changes to Streamline Local Housing Approvals, we cautioned that efforts to streamline approvals could be undermined if local planning and zoning rules do not provide adequate opportunities for projects to take advantage of this streamlining. The state’s primary existing tool for combatting the problem of inadequate planning and zoning is housing element law. Housing element law requires cities and counties to develop a plan that demonstrates how their planning and zoning rules will accommodate future home building.

In this report, we review the available evidence to gauge whether housing elements achieve their objective of ensuring that local communities accommodate needed home building. Our review suggests that housing elements fall well short of their goal. Communities’ zoning rules often are out of sync with the types of projects developers desire to build and households desire to live in. As a result, home building lags behind demand.

There are no easy solutions to this problem. Although we offer a few changes the Legislature could consider, real improvement can come only with a major shift in how communities and their residents think about and value new housing. Such a change is unlikely to happen on its own. Convincing Californians that significantly more home building could substantially better the lives of future residents and future generations necessitates difficult conversations led by elected officials and other community leaders interested in those goals. Unless Californians are convinced of the benefits of significantly more home building—targeted at meeting housing demand at every income level—no state intervention is likely to make significant progress on addressing the state’s housing challenges.

How Local Governments Plan For Housing

California’s cities and counties make most decisions about when, where, and to what extent housing will be built. Below, we describe the basics of how local governments plan for new housing.

General Plan Defines a Community’s Long‑Term Vision

General Plan Charts Path of Future Development. Every city and county in California is required to develop a general plan that outlines the community’s vision of future development through a series of policy statements and goals. A community’s general plan lays the foundation for all future land use decisions, as these decisions must be consistent with the plan. General plans are comprised of several elements that address various land use topics. Seven elements are mandated by state law: land use, circulation, housing, conservation, open‑space, noise, and safety. The land use element sets a community’s goals on the most fundamental planning issues—such as the distribution of uses throughout a community, as well as population and building densities—while other elements address more specific topics. Communities also may include elements addressing other topics—such as economic development, public facilities, and parks—at their discretion.

Housing Element Outlines How a Community Will Meet Its Housing Needs. Each community’s general plan must include a housing element, which outlines a long‑term plan for meeting the community’s existing and projected housing needs. The housing element demonstrates how the community plans to accommodate its “fair share” of its regions housing needs. To do so, each community establishes an inventory of sites designated for new housing that is sufficient to accommodate its fair share. Communities also identify regulatory barriers to housing development and propose strategies to address those barriers. State law generally requires cities and counties to update their housing elements every eight years. The fourth housing element planning cycle, which began sometime between 2006 and 2008 for most cities and counties, recently ended. Most cities and counties now are a couple years into their fifth planning cycle.

Regional Housing Needs Allocation Process Defines Each Community’s Fair Share of Housing. Each community’s fair share of housing is determined through a process known as Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA). The RHNA process has three main steps:

- State Departments Develop Regional Housing Needs Estimates. To begin the process, the state department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) estimates the amount of new housing each of the state’s regions would need to build to accommodate projected household growth. Household growth projections are based on an analysis of demographic trends and population growth estimates from the state Department of Finance. Each region’s housing needs are grouped into four categories based on the anticipated income levels of future households: very‑low, low, moderate, and above‑moderate income. (Very‑low income is defined as less than 50 percent of an area’s median income, low income 50 percent to 80 percent, moderate income 80 percent to 120 percent, and above‑moderate income more than 120 percent.)

- Regional Councils of Government Allocate Housing Within Each Region. Next, regional councils of governments (regional planning organizations governed by elected officials from the region’s cities and counties) allocate a share of their region’s projected housing need to each city and county. Cities and counties receive separate housing targets for very‑low, low, moderate, and above‑moderate income households. Each council of government develops its own methodology for allocating housing amongst its cities and counties. State law requires, however, that each region’s allocation methodology be consistent with their Sustainable Community Strategy—a state‑mandated long‑range regional strategy to reduce regional greenhouse gas emissions through transportation and land use planning.

- Cities and Counties Incorporate Their Allocations Into Their Housing Elements. Finally, cities and counties incorporate their share of the regional allocation into their housing element. Communities typically do so by demonstrating how they plan to accommodate their projected housing needs in each income category.

Some Communities Do Not Comply With Housing Element Requirements. State law requires HCD to review each community’s housing element for compliance with state requirements. In recent years, HCD has found that most (around 80 percent) housing elements comply with state laws. A minority of communities, however, have either adopted a noncompliant housing element or failed to submit their housing element to HCD for timely review. Communities without an approved housing element face limited ramifications. Noncompliant communities are ineligible for various housing‑related state grant funds, which represent a very small share of local government resources. Courts may also suspend a local government’s permitting authority until its housing element is approved, although this may have limited effect on communities less inclined to development.

Zoning Implements the General Plan

Zoning Is the Primary Tool for Implementing the General Plan. Cities and counties enact zoning ordinances to turn the broad policy goals outlined in their general plans into property‑specific requirements. A community’s zoning ordinance typically defines each property’s allowable use and form. Use dictates the broad category of development that is permitted on the property—such as single‑family residential, multifamily residential, or commercial. Form dictates building height and bulk, the share of land covered by buildings, and the distance of buildings from neighboring properties and roads (known as setback). Zoning ordinances also often place additional restrictions on property owners—such as minimum parking requirements—to mitigate a property’s potential effects on surrounding properties.

Zoning Determines the Type of Housing Built. Rules about form effectively determine how many housing units can be built on a particular site (referred to as housing density). A site with one‑ or two‑story height limits and large setbacks typically can accommodate only single‑family homes. Conversely, a site with height limits over one hundred feet and limited setbacks can accommodate higher‑density housing such as multistory apartments. Rules such as minimum parking requirements also can shape housing densities. If a community requires abundant on‑site parking, a developer would have to dedicate more land to parking lots, reducing the number of housing units that can be built.

Zoning Key to Meeting Housing Needs. Zoning rules determine the size of a community’s housing stock by dictating how many sites housing can be built on and at what densities. Zoning rules, therefore, must allow for new housing on a sufficient number of sites and at sufficient densities if a city or county is to meet its community’s housing needs.

Back to the TopPlanning for New Housing Often Falls Short

Housing element law asks cities and counties to ensure that their planning and zoning rules adequately accommodate future housing needs. This is an incredibly difficult task, made more difficult by residents’ resistance to building more housing. As a result, communities’ zoning rules often are out of sync with the types of projects developers desire to build and households desire to live in. This, in turn, often results in too little housing being built to meet demand.

Housing Element Headwinds

Forecasting Housing Needs Is Hard. A community’s future housing needs are almost impossible to predict with precision. These needs depend on a multitude of factors, many of which are largely outside of the state’s and local communities’ control—such as demographics, employer location decisions, broader economic trends, and happenstance. Because of this, projections of future housing needs developed through the RHNA process are imperfect at best.

Beyond the inherent difficulty of forecasting, other factors can drive a wedge between RHNA projections and actual demand for housing. The most important of these factors is the reliance on projections of household growth as an indicator of demand for housing. These projections are based, in part, on extrapolations from past trends in population growth, migration, and household formation. Past demographics trends, however, fail to capture the full extent of demand for housing. As we discussed in California’s High Housing Costs: Causes and Consequences, California has a significant housing shortage—that is, too little housing is built to accommodate all those who wish to live here. This shortage means that households compete for limited housing, bidding up home prices and rents. Households unwilling or unable to pay these high costs are forced to live somewhere else. Households forced to live somewhere else do not show up in California’s past demographic trends and therefore are not reflected in RHNA calculations. They nonetheless contribute to the state’s heightened competition for housing and resulting high housing costs. Failing to account for this unmet demand can cause projections of housing needs to fall short of actual demand for housing.

Identifying Ideal Sites for Development Also Is Difficult. It is also difficult for communities to anticipate which particular sites will be profitable for developers to build on in the future. This is because developers’ decisions about which sites to build on and when are based on a multitude of considerations, many of which are not apparent to planners or rely on information available only to developers. These considerations also can change significantly over time. In addition, decisions of landowners can significantly influence which sites are developed. In some cases, planners and builders may agree that certain sites would be ideal for new housing but landowners may be unwilling to sell their land to home builders. As we discussed in Common Claims About Proposition 13, this may be exacerbated by California’s property tax system which can encourage landowners to hold onto vacant or underutilized properties longer than they otherwise would.

Community Resistance Complicates Already Difficult Task. The difficulty of crafting planning and zoning rules that accommodate future growth is often compounded by resistance from residents. Residents often push back against projections of future housing needs, question whether it is their community’s responsibility to accommodate such growth, and attempt to block necessary zoning changes. This resistance is understandable and perhaps inevitable. Many residents see new housing—and the changes it will bring to their community—as a threat to their well‑being. At the same time, many who would benefit from new housing in a community do not live there and therefore have little say in planning decisions. This imbalance results in many residents looking unfavorably upon new housing.

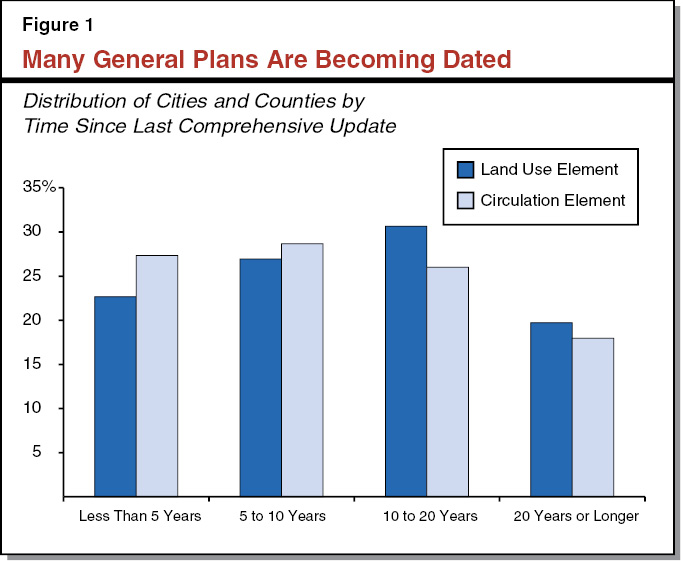

Outdated Plans. Reflective, in part, of their residents’ disfavor towards new housing, many communities seem to place a low priority on updating their planning and zoning standards to accommodate future housing needs. As shown in Figure 1, about half of cities and counties have not completed a comprehensive update of two major elements of their general plans (land use and circulation) in over a decade. About one‑fifth of cities and counties have gone longer than 20 years without an update.

Practical Limitations of HCD Oversight. Although HCD reviews each community’s housing element, resource constraints and lack of knowledge of a locality’s particularities limit what this review can achieve. Over the course of a few years, HCD staff are tasked with reviewing the housing elements of the state’s 58 counties and 482 cities. Many housing elements are lengthy and complex documents. Some housing site inventories contain thousands of properties—for example, the city of Los Angeles’ site inventory contains over 20,000 sites. To carry out this task on a statewide basis, HCD receives just under $1 million dollars annually to fund seven staff. In contrast, local planning departments—which are tasked with developing, implementing, and enforcing general plans and zoning and building codes—receive over $1 billion per year in total funding from local sources. In addition to having far greater resources, local planning departments also have more insight into their local communities. Faced with these realities, HCD’s reviews of housing elements often cannot extend beyond ensuring that communities have complied with the law’s basic procedural requirements. Perhaps most importantly, HCD lacks the capacity to thoroughly vet the thousands of potential housing sites identified in communities’ housing elements.

Evidence That Housing Element Process Falls Short of Goals

Recent RHNA Projections Appear Misaligned With Housing Demand. As we discussed in more detail in A Look at Recent Progress Toward Statewide Housing Goals, comparing RHNA goals to actual building in recent years suggests that RHNA goals did not fully capture demand for housing in many communities. This is best illustrated by looking at the San Francisco Bay Area. During the 2014 through 2016 period Bay Area communities (those in Alameda, Contra Costa, San Mateo, San Francisco, and Santa Clara) permitted roughly the amount of housing projected to be needed via the RHNA process. Nonetheless, there remains significant evidence of unmet demand for housing. Typical rents exceed $2000, more than double the national average. Available rental housing also is difficult to find. As of 2015, vacancy rates (the share of all rental housing available to new tenants) were around 2.5 percent, less than half the national average.

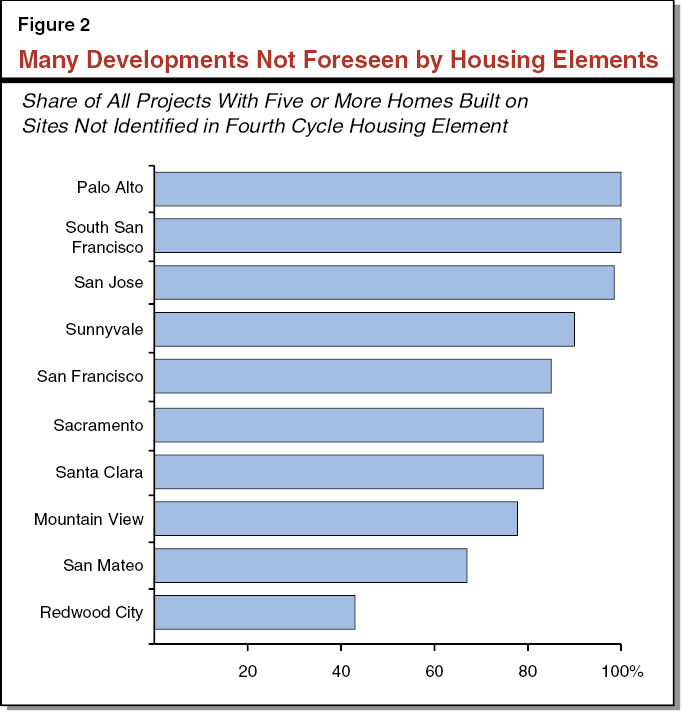

Fourth Cycle Housing Elements Often Failed to Anticipate Future Development. Communities’ plans for accommodating housing growth during the fourth planning cycle also appear to have often been out of sync with the home building that actually occurred. Our review of home building in cities for which we could obtain data suggests that the majority of larger housing developments (those with five or more homes) were constructed on sites that were not identified for housing in a jurisdiction’s housing element. Figure 2 shows our estimates of the share of all larger housing developments that were built on unplanned sites in select cities. (These numbers are rough estimates based on publicly available information. Data quality and timing issues complicate this analysis. Readers should focus on the general magnitude of the numbers and not the precise estimates.) As the figure shows, failure of housing elements to anticipate future development patterns seems to be ubiquitous among the cities surveyed.

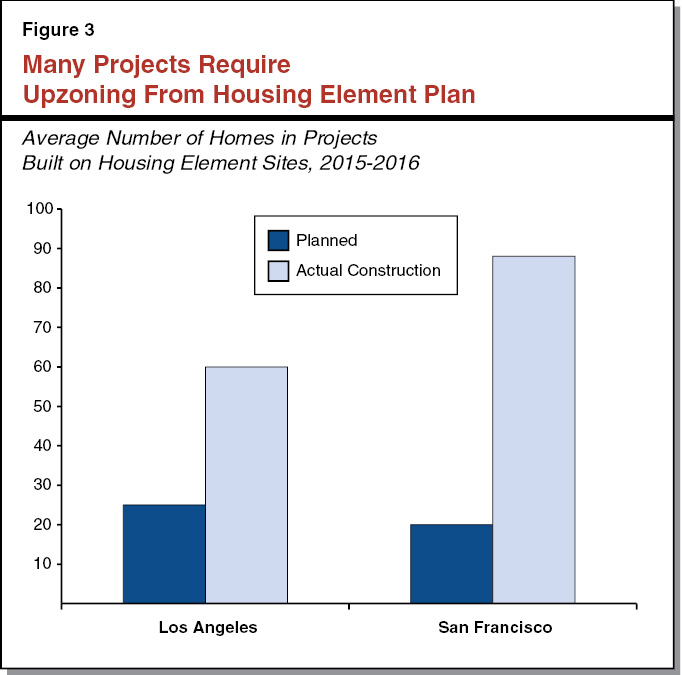

Pattern Appears to Have Continued in Fifth Cycle. To date, this pattern appears to have continued into the fifth planning cycle. Roughly two‑thirds of larger housing developments permitted in 2015 through 2016 in the cities of Los Angeles, San Francisco, and San Jose appear to be on sites not identified in a housing element. Further, we could not identify any recently permitted developments in Sacramento that will be built on the city’s housing element sites. Among the minority of projects permitted on housing elements sites, many projects appear to have needed a change to zoning rules despite being on a planned site as shown by Figure 3. In San Francisco, the typical project was permitted for more than three times the number of housing units planned for in the housing element. Similarly, the typical project in Los Angeles was permitted for more than twice the number of units as planned.

Drag on Home Building

Housing Element Shortfalls Can Limit Housing Production. Housing production lags when housing elements fail to anticipate the types of housing developers will be interested in building and households will be interested in living in. This is because many projects will have a need for changes to planning and zoning rules which often require a lengthy approval process, if they are approved at all.

Sites Overlooked in Housing Element Likely Need Zoning Changes to Accommodate Housing. When a proposed project is inconsistent with planning and zoning rules, a developer must ask the city or county to modify these rules. The housing element process is meant to forestall the need for these types of changes, as communities are supposed to make proactive zoning changes to accommodate home building on designated sites. If sites are overlooked, however, these zoning changes likely do not occur. Because of this, zoning rules for overlooked sites often can prohibit development—for example, the property’s allowable uses may not include housing or its allowable housing density may be too low for profitable development. Further, sites identified in a housing element may be planned for lower housing densities than would be profitable for developers. The data above suggests that these challenges are present for many projects.

Need for Zoning Changes Raises Costs, Discourages Home Building. A request for zoning changes can involve multiple administrative processes and public hearings and often takes several months or years to complete. One past survey of local building officials found that an average zoning change takes just under a year to complete in California’s high demand coastal jurisdictions. Further, some changes may not be approved at all or may be approved only if developers meet other conditions not outlined in planning or zoning rules. These delays and uncertainties increase costs for home builders and discourage builders from pursuing certain projects. A study of jurisdictions in the Bay Area found that each additional layer of review a typical project must complete is associated with a 4 percent increase in a jurisdiction’s home prices.

Back to the TopHow Should the State Respond?

In the prior section, we discussed evidence that suggests the state’s primary tool to ensure that local governments adequately plan for new housing—the housing element process—falls short of its goal. How should the state respond? There unfortunately is not an easy answer to this question. Some options are available that might bring about limited improvement. Ultimately, however, major improvements will require a substantial shift in how communities and their residents think about and value new housing.

Options to Consider

Modify RHNA Projections. The process of developing RHNA projections could be improved to better account for unmet housing demand and give communities a more realistic idea of their housing needs. One option could be to adjust the current demographic‑based projections to account for signs of unmet housing demand, such as high rents or low vacancy rates. Our modeling of California’s housing markets in California’s High Housing Costs: Causes and Consequences suggested that there is roughly a one‑to‑one relationship between long‑term housing supply growth and long‑term housing cost growth. Consistent with this, one option could be to adjust upward RHNA goals for communities with high rents by an amount proportionate to how much their rents exceed the statewide norm. For example, a community whose rents are 25 percent above the statewide average and whose current total RHNA goal is 1,000 could instead be assigned a goal of 1,250.

Increase Local Fiscal Incentives to Build Housing. As we discussed in California’s High Housing Costs: Causes and Consequences, cities and counties face fiscal incentives that are adverse to new housing. Few city and county revenue sources grow proportionately with increases in population. This can lead to fears that accommodating new housing—and therefore new people—will increase demands for public services faster than the funding available to pay for those services. This can, in turn, amplify communities’ anxieties about allowing new housing.

To counter this, the Legislature could look to allocate more funding to locals on the basis of population growth. To do so, the Legislature could consider three options, each of which presents challenges:

- Modify Existing State Funding Allocations. The Legislature could modify existing state funding allocations to cities and counties so that they are distributed based on population growth. Currently, however, discretionary state allocations to cities and counties are minor, representing a very small portion of city and county funding.

- Allocate New Funding Streams Based on Population. The Legislature also could look to allocate any new funding streams to cities and counties based on population growth. This option likely would be limited by the need to pursue other policy objectives. For example, a new funding stream aimed at paying for maintenance of existing infrastructure may be less effective if allocated based on population growth, as maintenance needs and population growth may not be well aligned.

- Alter Allocation of Local Taxes. The Legislature also could consider reallocating local government tax revenues—particularly property or sales taxes—so that these allocations better reflect population growth. Such changes would face several hurdles. The State Constitution significantly limits the Legislature’s ability to alter the allocation of local revenues. Also, past attempts to change the allocation of local property taxes or sales taxes have faced stiff resistance from local agencies concerned that such changes would create winners and losers and disrupt the financial health of some communities. One possible—albeit difficult—option could be to allocate some or all of future growth in local property and/or sales taxes within each county to the jurisdictions within the county based on their population growth. Making this change for property taxes would require a two‑thirds vote from in the Legislature, while such a change for sales taxes would require a voter‑approved change to the state constitution.

Streamline Local Approvals . . . Last May—in Considering Changes to Streamline Local Housing Approvals, our office recommended that the Legislature strongly consider a proposal from the Governor to streamline local approvals for certain housing. We also suggested going beyond the Governor’s proposal by expanding it to include a broader category of housing development. We continue to recommend the Legislature look for ways to streamline local approvals. Doing so would not directly improve planning and zoning outcomes. Nonetheless, it would avoid compounding the challenges for the many housing projects already facing lengthy reviews to obtain zoning changes.

. . . But Be Realistic About What Can Be Achieved. At the same time, it is important to keep in mind that the effectiveness of state actions to streamline approvals likely would be limited without major improvements in planning and zoning at the local level. Unless local planning and zoning rules provide adequate opportunities for housing development, few projects may be able to take advantage of a faster approvals process.

Improvement Will Be Limited Without a Shift in Views About Housing

While more dramatic changes to preempt local decisions could be considered, many local communities have fervently opposed, obstructed, or even disregarded such changes in the past. Cities and counties have long been vested with broad authority over planning decisions. This assignment of authority to cities and counties reflects a deeply held desire of the state’s residents to control the environment of their communities and in many cases to maintain the status quo. Any major changes in how communities plan for housing will require their active participation and a shift in how local residents view new housing.

There is little indication, however, that such a shift is forthcoming. Convincing Californians that a large increase in home building—one that often would change the character of communities—could substantially better the lives of future residents and future generations necessitates difficult conversations led by elected officials and other community leaders interested in those goals. Unless Californians are convinced of the benefits of more home building—targeted at meeting housing demand at every income level—the ability of the state to alter local planning decisions is limited.