LAO Contacts

October 8, 2018

Evaluation of the Property Tax Postponement Program

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Affording Property Taxes in California

- Property Tax Postponement Program

- Evaluation of the PTP

- Policy Alternatives

Executive Summary

California Has High Housing Costs, but Property Tax Payments Are Near the National Average. Housing is very expensive in California—in early 2018, the typical California home cost $481,000, roughly double the price of the typical home in the United States. Proposition 13 (1978), which limits property tax growth after a home is purchased, has kept property tax payments relatively low by comparison. In fact, in 2016, the median property tax payment in California was $3,550, only somewhat above the national median of $2,350. Nonetheless, some homeowners in California face difficulty affording their property taxes.

Some Options Available to Homeowners Who Cannot Afford Property Taxes. Homeowners who cannot afford to pay their property taxes have some options to borrow against the equity in their homes and use those funds to pay their taxes. These options include home equity loans (which are only available to homeowners with sufficiently high credit scores and incomes) and reverse mortgages. In addition to these options, the state offers the Property Tax Postponement (PTP) Program to help certain homeowners afford their property taxes and stay in their homes. This report evaluates PTP.

How PTP Works. Homeowners qualify for PTP if they are: (1) over the age of 62, blind, or disabled; (2) have household incomes less than $35,500; and (3) own at least 40 percent equity in their home. Under PTP, the state pays a participating homeowners’ current‑year property taxes directly to the county on their behalf. Similar to a loan, homeowners (or their heirs) must eventually repay the state for these payments with interest. Homeowners can defer these repayments indefinitely, but must repay the state when the property is inherited (by someone other than a spouse), sold, or refinanced.

Evaluation

In this report, we identify a variety of advantages and shortcomings of PTP, organized into five areas:

- Eligibility. An advantage of PTP is that it provides guaranteed eligibility for those who qualify. The income eligibility threshold, however, does not vary by household size, is not indexed for inflation, and does not vary geographically. Moreover, PTP is not available to some lower‑income homeowners who could benefit from it.

- Participation. Participation in PTP is very low—a clear shortcoming of the program. In particular, in the most recent years, PTP has had around 1,000 participants—compared to the over one million Californians who are over the age of 62, own their own homes, and live in a household with incomes less than $35,500.

- Affordability. PTP has two advantages with respect to affordability: (1) PTP allows participants to indefinitely postpone repayments and (2) PTP loans are less costly than reverse mortgages. However, the PTP interest rate is too high—the Legislature very likely could set the interest rate lower while still keeping the program cost‑neutral.

- Budgetary. A key advantage of PTP is that it does not carry a cost to taxpayers. In fact, PTP provides a General Fund benefit—meaning low‑income participants in the program are effectively subsidizing the state’s General Fund. We are not aware of any other safety net program in state government that generates General Fund revenue.

- Administrative. PTP has high administrative costs and PTP participants must subsidize the relatively high costs associated with processing unapproved applicants.

Policy Alternatives

Option to Eliminate the Program. PTP has a very low participation rate and a high per‑participant administrative cost. Both of these factors suggest the program is providing little total benefit. As such, the Legislature may want to consider eliminating the program.

Options to Improve the Program. If the Legislature wants to maintain the program, we recommend a variety of changes to PTP to improve it. In particular, we suggest:

- Base Income Limit Thresholds on Regional Income Limits. The income threshold used by PTP to determine eligibility does not vary by household size or geography, nor does it increase with inflation. To address these issues, we recommend the Legislature base income eligibility on the “income limits” published each year by the Department of Housing and Community Development, which are tailored for county median income and household size.

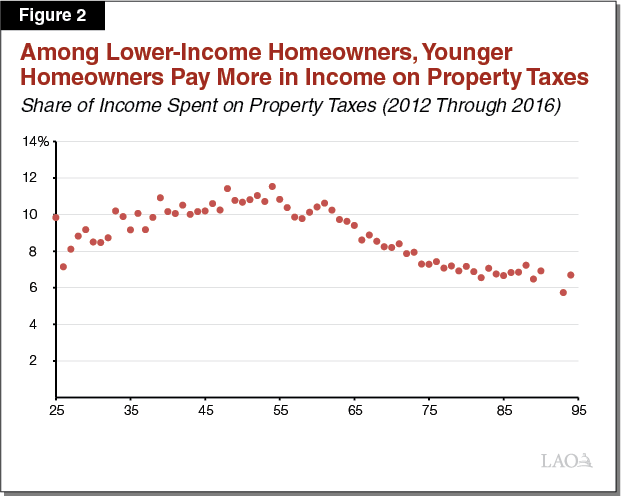

- Consider Expanding Eligibility by Lowering Age Requirements. In this report, we discuss why lower‑income homeowners who are younger than 62 could benefit just as much—or potentially more—than homeowners who are older than 62. In particular, low‑income homeowners in their 40s and 50s spend higher shares of their income on property taxes than older homeowners. The Legislature could expand eligibility by setting a different age threshold or eliminating the threshold entirely.

- Lower the Interest Rate and Eliminate the General Fund Benefit. PTP has an interest rate of 7 percent, which is high. The state could afford to lower the interest rate for PTP participants and keep the program self‑funded. Moreover, if program revenue exceeds its cost by a certain amount, that balance is deposited into the General Fund—meaning PTP provides a benefit to the state budget. We recommend the Legislature eliminate this General Fund benefit and lower the interest rate associated with the program.

- Couple Changes to Eligibility With Options to Limit State Risk. If the Legislature expands eligibility in the program, the changes could mean higher state costs from uncollectable loans. To address this risk, the Legislature could consider additional changes to balance these risks, including: adjusting the interest rate, limiting the total amount of deferment allowed, and limiting the number of years a homeowner—particularly a younger homeowner—can participate in the program.

Introduction

California home prices have been higher than the U.S. average since the 1940s. In the 1970s, California home prices began growing particularly quickly, significantly outpacing the growth in the rest of the nation. Late in that decade, the state established the Property Tax Postponement (PTP) Program to help low‑income seniors and people who are blind or disabled afford to pay their property taxes and stay in their homes. This report evaluates the PTP Program. We first describe the Californians that are most likely to face difficulty in affording their property taxes. We then provide an overview of the PTP Program and identify its advantages and shortcomings. We conclude with two different policy alternatives that the Legislature could consider based on our evaluation of the program.

Affording Property Taxes in California

In this section, we provide background on property taxes in California and how much Californians pay. We also discuss what happens when homeowners have difficulties paying their property taxes and identify some specific groups that may have more difficulty affording these taxes.

What Do California’s High Housing Prices Mean for Property Taxes?

Home Costs in California Are High. Housing is more expensive in California than in most of the rest of the United States. In early 2018, the typical California home cost $481,000, double the price of the typical U.S. home ($241,000). Although single‑family home prices in less costly areas of the state—such as Fresno and Bakersfield—are considered inexpensive by California standards, they are about average compared to the rest of the country.

Homeowners Pay Property Taxes on Their Homes. Homeowners pay property taxes directly to the county they live in based on the taxable value of their homes. Taxable value (or assessed value) is based on the property’s purchase price. Each property owner’s annual property tax bill is determined by multiplying the taxable value of her property by her tax rate. (As such, the property tax is an ad valorem tax because it is based on the value of the home.) For example, the owner of a property with a taxable value of $100,000 and a tax rate of 1 percent pays an annual property tax payment of $1,000.

Proposition 13 Places Limits on Property Taxes. Proposition 13, which was passed by voters in 1978, places two key limits on property taxes:

- Tax Rate. Proposition 13 limits a property’s base tax rate to 1 percent. (Below, we discuss how additional tax charges cause the rate on property tax bills to surpass this limit.) Before Proposition 13 passed, local governments were able to set property tax rates at the level they each determined appropriate.

- Growth in Taxable Value. Proposition 13 also limits the growth of a property’s taxable value to 2 percent or the rate of inflation, whichever is lower. In the year a property is sold, its taxable value is reset to the purchase price.

Average Property Tax Rate Is Slightly Higher Than 1 Percent. While Proposition 13 limits a property’s overall tax rate to 1 percent, most property tax bills also include additional ad valorem property taxes to pay for voter‑approved bonds. As a result, the average property tax rate paid in the state is 1.14 percent. These average rates varied from 1 percent in Alpine and Sierra Counties to 1.21 percent in Alameda County in 2016‑17.

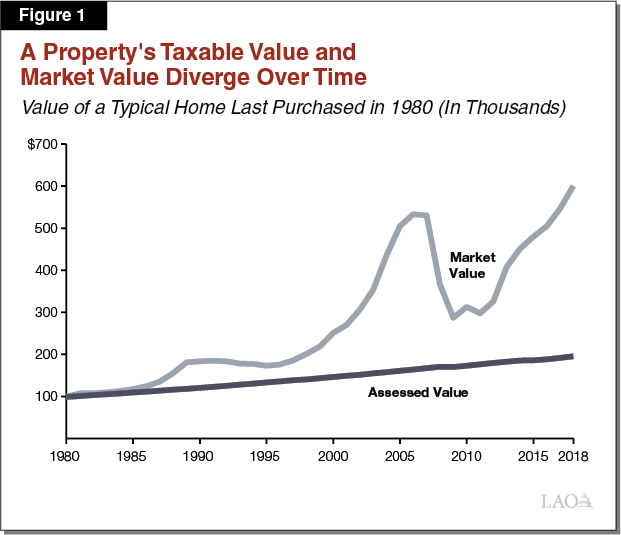

Growth in Market Value Generally Exceeds Growth in Taxable Value. Most properties’ market values grow faster than 2 percent per year. As a result, under Proposition 13, the taxable value of most properties is less than their market value. The longer a property is owned, the wider this gap tends to grow, as shown in Figure 1. As such, older homeowners—who have generally owned their homes for longer—tend to pay lower property taxes than younger homeowners.

High Housing Prices Do Not Directly Translate to High Property Taxes in California. While the cost of housing is high in California, Proposition 13 has prevented this from directly translating into high property taxes, particularly for homeowners who have owned their homes for many years or decades. On the other hand, property taxes are more expensive for people who recently purchased their homes. Compared to other states, while housing prices are high, property tax rates in California are relatively low. As a result, per person property tax collections are only somewhat above the national average. In 2016, the median property tax payment in California was $3,550, somewhat above the national median of $2,350.

What Happens to Those Who Cannot Afford Their Property Taxes?

Some Homeowners Face Difficulties Affording Their Property Taxes. For many Californians, the property tax is one of the largest tax payments they make each year. Property taxes are due to the counties in installments twice per year: once on December 10 and once on April 10. Some homeowners have difficulty paying these taxes on time. Homeowners who fail to pay their property taxes by these dates are considered delinquent. Delinquent homeowners pay a 10 percent penalty to the county for each late payment. They also must pay interest on delinquent taxes of 1.5 percent, which accrues each month the payment is still outstanding. The cost of these penalties and interest accumulate quickly, meaning a delinquent homeowner’s total outstanding debt to the county is often much larger than just the amount of past due taxes. The most recent data available suggest the statewide delinquency rate was 1.3 percent in 2016 (defined as the amount in unpaid property taxed due as a share of total taxes due). However, there is substantial variation in this rate at a county level. In 2016, the delinquency rate ranged from 0.6 percent in San Mateo County to 16.9 percent in Imperial County.

Homeowners Can Lose Their Properties for Property Tax Delinquency. State law requires counties to allow homeowners to enter into a payment plan for tax delinquent properties. As long as the homeowner makes payments according to the terms, the county will not sell the property. If a homeowner is delinquent on his property taxes for five years, the county can sell his home through a “tax sale.” Under a tax sale, the county lists a home for sale in the amount due in unpaid property taxes and fees at public auction. When properties are sold for more than the list price, other lien holders (for example, a mortgage lender) can request repayment of their debts by filing a claim with the county.

Tax Sales Are Relatively Rare. Tax sales as a share of all properties are relatively rare. For example, in 2016, Los Angeles County sold 842 residential and commercial parcels in three tax sales. For comparison, there are currently about 2.2 million residential and commercial parcels in Los Angeles County. In 2016, 69 properties were approved for tax sale in Placer County, but 47 were redeemed or removed prior to the sale (for example, because the homeowner paid the taxes) and so only 22 were actually offered at the auction.

Who Faces Difficulties Affording Their Property Taxes?

There are many reasons that a property enters a tax sale. From our discussions with county tax collectors, we understand that these reasons often include: (1) homeowners with a principal residence who are unable to afford their property tax payments, (2) developers with unfinished housing projects, and (3) heirs who are not aware that they now own the property or cannot afford the tax payments. The remainder of this section focuses on the first group, describing those who might be least likely to be able to afford their property tax payments on their principal residence.

Older Homeowners Have Lower Incomes, but More Wealth and Pay Less in Property Taxes. Homeowners in their 60s are often are no longer working. As a result, they often have less income than those who are younger. In 2016, for example, homeowners aged 62 to 71 had median household incomes of around $48,000, compared to homeowners aged 42 to 51, who had median incomes of $88,000. However, older homeowners also tend to:

- Pay Less in Property Taxes. Older homeowners, on average, have owned their properties for longer. Because Proposition 13 (1978) holds property taxes relatively constant in real terms over time, these homeowners pay less in property taxes, on average, than younger homeowners. For example, in 2016, homeowners aged 62 to 71 paid median property taxes of $3,050, compared to homeowners aged 42 to 51, who paid median property taxes of $4,450.

- Hold More Wealth. Because older homeowners have owned their homes for longer, the amount of home equity they hold also tends to be higher. (Equity is the difference between the market value of a home and the debts held against the home, such as a mortgage.) For example, in 2016, homeowners aged 62 to 71 held an average of 75 percent of equity in their homes, compared to homeowners aged 42 to 51, who held an average of about 60 percent. However, home equity is an illiquid asset that homeowners can only access, typically, by selling or mortgaging their home.

Low‑Income, Younger Homeowners Pay Higher Shares of Income Toward Property Taxes. Figure 2 shows the median share of income spent on property taxes by age of homeowners for those whose incomes are lower than $35,500 per year. The figure shows that low‑income homeowners of all ages pay higher shares of their income toward property taxes than other homeowners do. Among lower‑income homeowners, those who spend the most on property taxes are actually those in their 40s and 50s, rather than the oldest homeowners. This is because older homeowners tend to pay lower property taxes than younger homeowners as a result of Proposition 13. So, holding income roughly constant as Figure 2 does, older homeowners tend to pay lower shares of their income toward property taxes.

Working Age Homeowners Are More Likely to Have Temporary Periods of Low Income. Homeowners who are younger than retirement age and are not disabled are more likely to be able to participate in the labor force, earning income. However, working age people can sometimes experience a temporary reduction in income as a result of a job loss or illness, and, for a period of time, may not be able to afford their property taxes. Because Proposition 13 limits growth in property taxes from year to year, for working age homeowners, these affordability issues might more often be temporary, rather than permanent.

What Are the Private Sector Options to Help Homeowners Pay Property Taxes?

Private Sector Financing Options Can Help Homeowners Pay Property Taxes. When homeowners cannot afford to pay property taxes, they have some options to borrow against the equity in their homes. These loans are available to homeowners for any purpose, but can be used to finance property taxes. In particular, there are two common financing options available to homeowners who meet the requirements:

- Home Equity Loans or Lines of Credit. Home equity lines of credit and home equity loans allow a homeowner to borrow against the equity held in the home. Similar to a mortgage, home equity loans and lines of credit are secured against the borrower’s home. However, these loans must be repaid (in many cases, starting immediately) and not all homeowners have enough income or sufficiently high credit scores to access them.

- Reverse Mortgages. Reverse mortgages are a type of home equity loan that are available only to seniors. The most common type of reverse mortgage is the Home Equity Conversion Mortgage (HECM), described in the nearby box. Unlike home equity loans or credit, (1) homeowners can defer repayments on reverse mortgages indefinitely and (2) all homeowners who meet the eligibility criteria for the program qualify for them, regardless of income or credit worthiness.

Reverse Mortgages

Home Equity Conversion Mortgage (HECM). HECMs are the most common type of reverse mortgages—making up more than 95 percent of the U.S. reverse mortgage market since the early 2000s. (The rest of the reverse mortgage market is made up of proprietary reverse mortgages, which are privately financed and are more readily available to people with higher‑value homes.) HECMs allow seniors to take out a loan that accesses the value of the equity in their homes and use it for any purpose (including, for example, to pay property taxes). When a homeowner takes out a HECM loan, the private lender records a lien on the property. These loans are insured by the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) against the risk that the balance of the loan grows to exceed the value of the home.

Applying for a HECM. To qualify for a HECM loan, a homeowner must be 62 years old or older, occupy the home, be able to pay property taxes and insurance, and keep the house in good condition (HECM homes must meet FHA standards). Homeowners must either own their homes free and clear or, if they do not, the HECM loan cannot exceed the value of the homeowner’s equity.

Amount, Frequency, and Duration of Loans. The amount a borrower can receive from an HECM loan is determined by a formula, which is based on a variety of factors, including the property’s appraised value and the homeowner’s age. In 2016‑17, the average HECM loan in California had an initial principal limit (the present value of loan proceeds available to the borrower) of $283,000. Homeowners can receive payments in five different plan types, which vary by tenure and term. For example, a homeowner can receive the loan in equal monthly payments for as long as they occupy the home or as a flexible line of credit.

Cost of the Loan. HECM loans carry two types of major costs: an interest rate and fees. The average interest rate charged on HECM loans in California in 2016‑17 was 4.53 percent. In addition to the interest rate, the homeowner pays substantial fees as part of the loan and to the private lender who administers the loan. The largest of these fees is the mortgage insurance premium (which pays for the FHA‑backed mortgage), which is charged up front at 2 percent of the appraised value and ongoing of 0.5 percent of the loan balance for standard HECM loans. Borrowers typically pay for these fees using the loan proceeds.

Repayments Can Be Deferred Indefinitely. Repayments on HECMs can be deferred indefinitely, but a loan becomes due and payable if the borrower: passes away, moves away from the home, sells the home, or fails to pay the home’s property taxes or insurance.

Cost of Financing Involves Interest and Fees. Both of these financing options involve two main types of costs to the homeowner: an interest rate and fees. An interest rate is charged as a percentage of the total loan. Fees associated with reverse mortgages and/or home equity loans include: appraisal fees, closing costs (such as attorney’s fees, fees for preparing and filing a mortgage, fees for title search, taxes, and insurance), and loan origination fees.

Property Tax Postponement Program

Under PTP Program, State Pays Property Taxes on Behalf of Eligible Homeowners. The state offers the PTP Program to help certain homeowners afford to pay their property taxes. Under PTP, the state pays a participating homeowner’s current‑year property taxes directly to the county on his or her behalf (meaning that PTP cannot cover past due or delinquent taxes owed). To participate, homeowners must meet eligibility requirements and apply for the program. Similar to other financing options, the homeowner (or his or her heirs) must eventually repay the state for these payments with interest. The program is administered by the State Controller’s Office (SCO). The remainder of this section describes: (1) the history of PTP, (2) how PTP works, and (3) how PTP is funded.

History of PTP

Voters Authorized Property Tax Postponement in 1976. In 1976, the Legislature placed a constitutional amendment on the ballot (Proposition 13) authorizing itself to “provide by law for the manner in which a person of low and moderate income, age 62 or older may postpone ad valorem property taxes” on his or her principal dwelling. An amendment was needed to operate such a program because the California Constitution stipulates that “all property is taxable” and courts have required the state to uniformly apply property taxes. As a result, all exemptions from the property tax—like those for public schools—are constitutionally provided.

Legislature Established PTP in 1977. Following the voters’ approval of Proposition 13 in 1976, the Legislature established PTP in statute in 1977. In the first year of operation, 1977‑78, nearly 13,000 people applied for PTP. A year later, when voters passed Proposition 13 of 1978, which limited taxes on property to 1 percent of its taxable value, participation declined sharply and about 8,500 people applied. At the time, PTP was administered by both SCO and the Franchise Tax Board (FTB).

Eligibility Expanded to People Who Are Blind or Disabled in 1984. In 1984, the Legislature placed another constitutional amendment on the ballot, this time expanding its authority to provide for the deferral of property tax payments by people who are blind or disabled. Voters approved the amendment (Proposition 33), and shortly thereafter the Legislature passed legislation that implemented the program expansion.

Legislature Suspended PTP in 2009. The state continued operating the program for a few decades until it faced budget deficits following the financial crisis in 2008. As one of many actions the state took to balance the budget, the Legislature suspended PTP in 2009. After suspension, SCO could not make property tax payments on behalf of new or existing participants, but still administered repayments for existing participants.

During Suspension, Legislature Authorized County Property Tax Deferment Program. In 2011, after suspending PTP, the state authorized participating counties to operate their own property tax postponement programs with their own funds. Counties must use similar eligibility requirements and rules as PTP in establishing these programs. Based on this authority, Santa Cruz established a property tax postponement program and began making repayments for participants in 2012‑13. We do not know of any other California counties that have operated their own property tax deferral programs.

Legislature Reauthorized PTP in 2014. In 2014, the Legislature reinstated PTP, with significant modifications, in Chapter 703 (AB 2231, Gordon). SCO began accepting new applications for PTP in 2016 and began making payments to counties on these homeowners’ behalf for tax year 2016‑17. (Santa Cruz County operated its own deferment program through 2015‑16, and suspended it after the state reinstated PTP.)

How PTP Works

This section describes how PTP works, organized around the four important steps in the process. First, homeowners submit annual applications to SCO to participate in PTP. Second, SCO reviews those applications and accepts or rejects them. Third, on behalf of those applicants that are accepted, SCO makes property tax payments to counties. Finally, the applicant (or another party, like an heir) repays SCO for the tax payments.

Homeowners Submit Annual Applications to SCO

Eligibility for PTP Based on Three Main Criteria. Homeowners apply for PTP each year between October 1 and February 10. Homeowners can qualify for PTP if they: (1) are over 62 years old, disabled, or blind; (2) have household income less than $35,500; and (3) own at least 40 percent equity in their home. (Before the program was suspended, the equity requirement was 20 percent.) Statewide, on average, approved applicants are 72 years old, have household incomes of about $20,000, and own 85 percent equity in their homes. Additionally, the applicant’s home must be a single‑family or multifamily unit and the applicant must use it as his or her primary residence. There are no eligibility requirements for creditworthiness (SCO does not run a credit check on applicants). Homeowners are not permitted to participate in PTP if they already hold a reverse mortgage (although no similar requirement exists for home equity loans).

Homeowners Must Requalify Each Year. Homeowners must submit their applications annually and requalify for the program each year. (Before the program was reinstated, homeowners only needed to qualify once and then could apply to stay in the program if needed, but did not need to requalify.) Using data from accounts paid in full during 2016‑17 and 2017‑18, about 30 percent of applicants used the program only once. Roughly 60 percent of participants used the program for five years or fewer.

SCO Reviews and Assesses Applications

SCO Accepts Around 65 Percent of Applications. SCO received about 1,300 applications for the PTP Program in 2016‑17 and 2017‑18 and approved around two‑thirds of these applications. In each of these two years, over 400 applications were denied for various reasons, such as the homeowner failed to complete the application or did not meet the required qualifications. Among these, most commonly, applicants were rejected because their household income exceeded the maximum threshold.

SCO Makes Property Tax Payments to Counties for Approved Applicants

SCO Pays Entire Property Tax Bill Directly to County. Once an application is accepted, SCO makes a one‑time payment for the homeowners’ entire property tax bill directly to the county in the first week of the month following acceptance. (SCO’s application period opens in October and so SCO makes these payments to counties between November and June of each year.) The average amount of these payments was $3,200 in 2017‑18. After accepting an application, SCO records a notice of lien with the county on the home of the participating homeowner.

Homeowners Still Need to Make Property Tax Payments When Application Is Pending. Homeowners who are approved for PTP do not need to pay the county late penalties or fees even if they missed an installment. Denied applicants who miss an installment still owe the outstanding amount, including delinquent fees, to the county. To avoid these fees, SCO advises applicants with pending applications to still pay the first installment of their property taxes on time. If their PTP application is accepted, the state will pay the homeowner’s full property tax payment and the county will reimburse the amount paid.

Total Value of Postponed Taxes Cannot Exceed Estimated Value of Home Equity. SCO does not allow the total amount of postponement to exceed the estimated value of the applicants’ home equity. (The total amount of postponement is equal to the sum of all postponed property tax payments, including the first year.) There are two important determinants of home equity value: (1) the homeowners’ existing outstanding debt and (2) the market value of the home. SCO uses a property and ownership search engine to verify the amount of outstanding debt on a property—including a mortgage, home equity line of credit, and tax liens. SCO estimates the market value of the home by comparing the property to recently sold surrounding properties on a number of specifications, such as its size in square feet and number of bedrooms. As a result, SCO does not require the homeowner to acquire an independent appraisal of the property. Each time a homeowner reapplies for the program, SCO reassesses the property for changes in both the homeowners’ outstanding debt and the estimated market value of the home.

Homeowners Repay SCO

Repayments Can Be Deferred Indefinitely. Program participants can defer their repayments on postponed property taxes indefinitely, but must repay the state when the property is inherited (by someone other than the applicant’s spouse), sold, or refinanced. Repayments also are triggered if the property owner moves, transfers title, defaults on a senior lien, or obtains a reverse mortgage. To ensure it can recover its costs, the state records a notice of lien on any property with postponed taxes in the program. When a home is sold by the homeowner or an heir, the state’s lien receives precedence in chronological order. That is, if a homeowner took out a mortgage in 2000 and a PTP deferment in 2014, the mortgage holder would receive payment on the outstanding amount before the state.

Homeowners or Heirs Repay the Loan With Interest. The state charges a flat, simple interest rate of 7 percent on PTP accounts. Before the program was suspended, the state charged a rate that varied based on the rate of return in the state’s checking account, known as the Pooled Money Investment Account. Between 1994‑95 and 2008‑09, this rate varied from 2 percent to 5 percent.

On Average, Accounts Are Repaid After 15 Years. The average length of postponement (from the first year an applicant entered the program to when their account was repaid in full) was 15 years. In 2016‑17, 70 participants, around 9 percent of the total, repaid in full within a year. When an account is fully repaid, SCO charges the account a one‑time fee of $8, which is paid to the county to release the state’s lien.

Some Accounts Are Not Repaid. Sometimes, a home is sold for less than the outstanding balance of the debt owed on the house. In some of these cases, the state is not able to recover its costs (particularly when the state’s lien is more recent than others). In 2016‑17 and 2017‑18, the default rate (the amount the state deemed uncollectable as a percent of the total amount collected) was 9 percent and 5 percent, respectively.

In the Event of a Tax Sale, the State’s Repayment Is Prioritized. In the event of a tax sale, the state’s lien does take priority over other lien holders. That is because the county is not permitted to sell the property for less than the outstanding balance of defaulted taxes, associated fees, and the outstanding balance of the PTP loan.

PTP Revenue and Costs

Program Costs Funded by Special Fund. PTP is operated using a special fund, the Senior Citizen and Disabled Citizens Property Tax Postponement Fund. (Before the program was suspended in 2009, the program was operated within the General Fund.) SCO deposits collections from homeowners making repayments into the account. SCO then uses the funds in this account to make property tax payments to the counties and to cover its administrative costs. SCO’s costs to administer the program were $2 million in 2017‑18.

Program Funded by Repayments and Interest. For the program to operate without General Fund support, PTP collections (repayments on existing loans) must exceed disbursements (payments to counties for new loans) and administrative costs. In any given year, disbursements and administrative costs can exceed collections as long as the program has sufficient carry‑in balances to cover its net costs. Historical data from the program indicate this has been the case over the long term. Between 1994‑95 (the first year for which the SCO has data) until program suspension in 2008‑09, collections exceeded the costs of disbursements and administration by an average of $1 million per year. (In some years, such as 2008‑09, disbursements did exceed collections.)

Under New Program, Excess Balances Swept to General Fund. When the program was reinstated and the Senior Citizen and Disabled Citizens Property Tax Postponement Fund was created, enacting legislation required balances in the fund above specified thresholds to sweep to the General Fund. In particular, fund balances above $20 million at the end of 2016‑17 and $15 million at the end of 2017‑18 (and each subsequent year) transfer to the General Fund. In 2017‑18, the balance of the fund exceeded the threshold by $5.7 million and that amount was transferred to the General Fund. The administration currently anticipates that $2.7 million will transfer in 2018‑19. Even before it was suspended in 2008‑09, the program provided net General Fund benefit over the long term, but because it was operated within the General Fund, no swap was required.

Evaluation of the PTP

This section provides an evaluation of PTP, including both advantages and shortcomings of the program. These are organized into five different areas, which are summarized in Figure 3 and described in more detail below.

Figure 3

Summary of the Evaluation of the Property Tax Postponement Program

|

Advantage |

Shortcoming |

|

|

Eligibility |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Participation |

||

|

||

|

Affordability |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Budgetary |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Administrative |

||

|

||

|

||

|

PTP = Property Tax Postponement Program. |

||

Eligibility

PTP Provides Guaranteed Eligibility for Those Who Qualify. All aged, disabled, or blind homeowners who meet the income and equity eligibility requirements for the program qualify for PTP, regardless of the value of their home or credit history. As such, PTP offers a financing option for homeowners who may not qualify for traditional loans. In that way, PTP and HECM programs are similar (although PTP has some advantages relative to HECM which we discuss later on in this evaluation).

PTP Is Not Available to Some Homeowners Who Could Benefit. PTP targets seniors and people who are blind or disabled with incomes less than $35,500. However, other homeowners could also benefit from the program. Figure 4 shows the share of household income spent on property taxes among homeowners at different ages and household income ranges (those in the first group qualify for PTP). Darker shades correspond with older homeowners, while lighter shades correspond with younger homeowners. Generally, at higher levels of income, homeowners of all ages spend lower shares of their income on property taxes. The figure suggests that other groups could potentially benefit even more from the PTP Program, including:

- Low‑Income Homeowners Younger Than 62. As the figure shows, among lower‑income households, older homeowners spend the lowest shares of their income on property taxes. Conversely, low‑income homeowners in their 40s and 50sspend the highest shares of their income on property taxes.

- Homeowners With Higher Levels of Income. Figure 4 also shows that homeowners in their 40s and 50s with household income above $35,500 also pay higher shares of income toward property taxes, relative to older homeowners. For example, those ages 42 to 51 with incomes between $35,000 and $45,000 spend about 6 percent of their income on property taxes, a higher percentage than those ages 72 and above at any income range displayed.

The PTP Income Threshold for Eligibility Has a Few Shortcomings. PTP uses one, fixed household income threshold for eligibility of $35,500. As a result, the threshold:

- Does Not Vary by Household Size. A single individual living alone with an income of $35,500 faces a different financial situation than a family of four living in a household with the same income. To account for these differences, other housing assistance programs usually vary eligibility based on both household income and size.

- Is Not Indexed for Inflation. PTP’s income threshold is not indexed for inflation. Household incomes rise over time with inflation. In future years, this will mean the current threshold will lose value. As a result, the proportion of homeowners who are eligible for the program will decline.

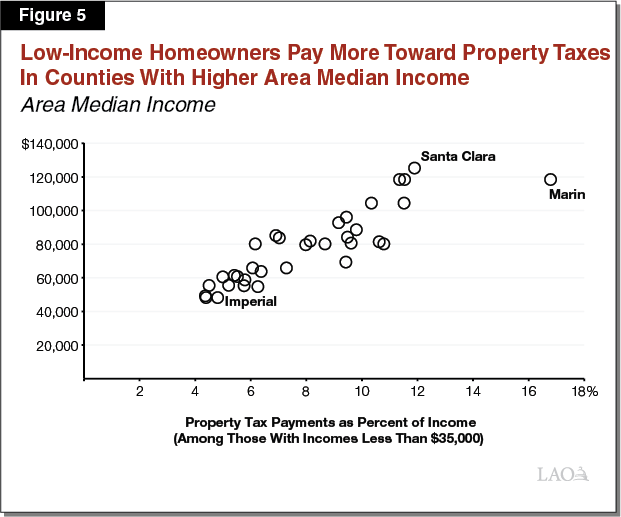

- Does Not Vary Geographically. The share of income that low‑income homeowners spend on property taxes varies substantially by geographic area. Figure 5 shows that lower‑income homeowners (those with incomes less than $35,500) in counties with higher area median incomes tend to spend higher shares of their incomes on property tax payments. For example, lower‑income homeowners in Santa Clara County, where the area median income is $125,000, pay an average of 12 percent of their income toward property taxes. Conversely, lower‑income homeowners in Imperial County, where the area median income is $48,200, pay just over 4 percent of their income toward property taxes. This is because places with higher area median income also have higher home prices. All else equal, a low‑income person living in Santa Clara County is likely to spend more on housing than a person with the same income living in Imperial County.

Participation

PTP Historically Has Had Low Participation. In 2008‑09, the last year the program was operated before suspension, SCO paid property tax payments on behalf of 5,676 homeowners. For comparison, in 2008, there were nearly one million Californians who were aged 62 or over, owned their homes, and lived in a household that had an income of less than $35,500. While not everyone who is eligible for the program will participate, this number of participants was still very low relative to the number of potential participants. In part, this low rate of participation may suggest that the program is not targeted toward those who are least able to afford their property taxes.

After Reinstatement, PTP Has Even Lower Participation. In the five years before suspension, the program received around 7,400 applications per year on average. In 2017‑18, the program received around 1,300 applicants and accepted about 900 of them. As such, while PTP had few participating homeowners even before it was suspended, it is even smaller today. The decline in applications could, in part, be the result of the suspension of the program and the resulting difficulty in outreach. Other new features of the program also might influence potential applicants not to apply, including the fact that the interest rate is now much higher.

Affordability

PTP Allows Participants to Indefinitely Postpone Repayments. PTP participants can defer their repayments on postponed property taxes indefinitely, with repayments triggered only if the homeowner passes away (and someone other than the spouse inherits the home), sells or refinances the home, moves, transfers title, defaults on a senior lien, or obtains a reverse mortgage. This provides a great deal of flexibility and affordability for participants, who may not have sufficient income to repay the outstanding balance on the loan until they can access their home equity, for example, by selling their home. In this way, PTP and HECM are similar.

PTP Loans Are Less Costly Than HECM Loans. HECM is much more expensive for participants than PTP. Although PTP carries a higher interest cost for homeowners (7 percent compared to 4.53 percent for HECM), PTP loans carry virtually no fees. HECM loans, by contrast, carry often significant, fixed upfront fees and additional annual costs for insurance. As described in the nearby box, the total cost, on average, to a homeowner to use PTP is typically lower than the cost to take out a comparable loan using HECM. (The average HECM loan, however, is much larger than the typical total deferment under PTP, suggesting these programs can serve different purposes.)

Comparing HECM and PTP

Average HECM Loan Is Much Larger Than Average PTP Amount. In 2016‑17, the average initial principal limit of Home Equity Conversion Mortgage (HECM) loans made to Californians was nearly $300,000. While not all participants will use the entire amount of their available loans, this average is significantly larger than the average amount of total property tax payments postponed under Property Tax Postponement (PTP). Data from the State Controller’s Office suggest the average participant uses PTP to postpone a total of $9,900 in property taxes—a much lower principal amount.

Cost of PTP Is Usually Lower Than HECM. While the interest rate associated with PTP is higher than the average rate charged on HECM loans, HECM loans have other fees that make them more expensive. Suppose a homeowner was choosing between PTP and HECM to help pay for five years of property taxes on a house with a taxable value of $300,000—representing around $18,000 in property taxes. Under PTP, the homeowner would repay the total principal amount plus about $1,200 in interest costs. Under HECM, assuming the current statewide average interest rate of 4.53 percent, the homeowner would repay roughly similar amounts for interest (because it is compounding, not simple), but would also pay $6,000 upfront and around $100 each year thereafter for the mortgage insurance premium and a few thousand dollars upfront for origination fees. These costs could be financed using the loan, but would result in a much higher total outstanding loan balance.

Homeowners May Prefer HECM for Larger Loans, but PTP for Smaller Cash Needs. As a result of these differences in the programs, homeowners may prefer to use HECM for more significant income‑support needs. In particular, a homeowner who needs many thousands of dollars per year to make ends meet or tens of thousands of dollars in a single year to make home repairs may prefer to access home equity through HECM. PTP, which provides less money to homeowners but is generally cheaper, may be a better option for those who face smaller annual shortfalls in their household budgets.

PTP Interest Rate Could Be Lower (While Still Keeping the Program Cost Neutral). The interest rate associated with a PTP loan needs to cover two major state costs: (1) SCO’s administrative costs and (2) state losses from delinquent loans. Even when the program operated at a much lower interest rate, its collections on existing accounts covered these costs over the long term. This suggests the interest rate is too high. That is, the state could afford to lower the interest rate for PTP participants and still keep the program self‑funded.

Budgetary

PTP Does Not Carry a Cost to Taxpayers. The PTP Program is self‑funded. That is, disbursements for property tax postponements and administration costs are paid using collections from existing accounts. As a result, PTP does not carry a cost to taxpayers.

PTP Should Not Provide a General Fund Benefit. As it is currently structured, PTP provides a General Fund benefit to taxpayers. That is because current law requires balances above $15 million in the Senior Citizen and Disabled Citizens Property Tax Postponement Fund to sweep to the General Fund. There is not a clear public policy rationale for generating a General Fund benefit from this program. In fact, if the purpose of this program is to keep people in their homes, it essentially is a safety net program. We are not aware of any other safety net program in state government that generates General Fund revenue.

General Fund Revenue Sweep Might Hamper Fund’s Long‑Term Sustainability. Over the long term, without the General Fund sweep, the program is likely to have enough funds to pay disbursements using collections. (This has been true historically and new features of the program, like annual applications, limit the state’s risk even further.) However, in some years, particularly in a recession, disbursements could exceed collections. In those years, the fund will need a reserve to cover these costs. The General Fund sweep limits the size of the program’s reserve, potentially hampering its long‑term sustainability.

Administrative

Administrative Costs Are High Relative to Program Benefits. The program currently costs about $2 million per year for SCO to administer. At the end of 2017‑18 SCO had 3,832 total outstanding accounts, meaning the state administrative cost for each participant was about $521 annually. These costs are high relative to the average postponement amount, which was $3,204 per person in 2017‑18.

Administrative Costs Are High Relative to Other State Programs. Elements of PTP’s program design mean that the administration costs of PTP are much higher than the costs the state incurred to run another program with the same objective. Specifically, the state used to administer the Senior Citizen Property Tax Assistance Program (PTAP), which is described in the box below. With the PTAP program, the FTB provided grants to low‑income seniors and people who are blind or disabled to help them defray the cost of property taxes. In the last year of operation, PTAP had over 600,000 participants and state administrative costs of $6.4 million—carrying an administrative cost per participant of $10. This program was relatively inexpensive to operate because processing most applications was routine. In particular, FTB required homeowners to file for the program with a copy of their tax return, meaning FTB could use automatic processes to confirm applicants’ income eligibility for the program.

Senior Citizen Property Tax Assistance Program (PTAP)

State Operated PTAP Between 1967 and 2009. Between 1967 and 2009, the state administered PTAP, a direct grant program to help low‑income seniors and people who are blind or disabled afford their property taxes. (In contrast to the Property Tax Postponement Program, which is a loan program, PTAP provided recipients with direct cash payments.) PTAP was administered by the Franchise Tax Board, which distributed payments and validated applicants’ eligibility using information from their annual tax filings. As one of the many actions the state took to address budgetary shortfalls in the Great Recession, the Legislature suspended the program in 2008‑09 and has not paid claims since that year.

Payments Averaged Around $300 Per Person. In the last year of operation, the average grant amount was $304 per person, in many cases covering a relatively small portion of a homeowners’ property tax costs. This grant amount varied based on a formula which took into account a person’s household income and the taxable value of their home. The program was available to both homeowners and renters. (Because renters do not pay property taxes directly, in these cases, grants were computed based on a property tax equivalent.)

Program Participants Pay for the Cost of Assisting Nonparticipants. We understand that one reason administrative costs of PTP are high is that the work to process applications is manual and time‑consuming. Also, SCO works with many applicants and potential applicants individually—sometimes involving multiple phone calls—to help them understand the program and to complete their applications on time. Many of the applicants SCO works with either do not ultimately apply for PTP or are not approved for the program. As a result, program participants are effectively paying for the cost of state assistance for those who do not ultimately participate.

Policy Alternatives

Below, we outline two different policy alternatives the Legislature could consider adopting based on our evaluation of PTP. Under the first alternative, the Legislature could eliminate the program. Under the second alternative, if the Legislature would rather leave the program in place, we offer a variety of options to improve the program that address many of the shortcomings we identify in our evaluation.

Eliminate the Program

Legislature May Want to Consider Eliminating the Program. PTP has a very low participation rate and a high per‑participant administrative cost. Both of these factors suggest the program is providing little total benefit. Moreover, the program may have had a stronger justification when it was originally established in 1977 at a time when there were no statewide constitutional limits on property tax rates or taxable values. Proposition 13 (1978), however, keeps annual growth in homeowners’ property taxes low and is likely a key reason that tax sales are relatively rare. This makes the public policy rationale for PTP less clear. As such, the Legislature might want to consider eliminating the program.

Some Ongoing Administrative Costs Would Still Be Necessary. Even if the Legislature eliminated the program for new applicants, SCO would require resources to process repayments on outstanding loans. As such, SCO’s administrative costs would likely decline to the levels during program suspension after 2009, which were about $500,000 per year. Administrative costs would continue until all remaining participants repaid their accounts, although the costs would likely decline over time. The state could continue to use program collections to pay for these costs and use the other incoming funds for General Fund benefit.

Improve the Program

If the Legislature instead wants to maintain the program, we would recommend a variety of changes to PTP. The first set of these recommendations is aimed at increasing participation and better aligning eligibility and benefits of the program with those who need it most. The second set of recommendations is aimed at helping the Legislature keep the program cost neutral for taxpayers even while expanding eligibility.

Improve Targeting of Eligibility

Base Income Thresholds on HUD Regional Income Limits. The income threshold used by PTP to determine eligibility currently does not vary by household size, geography, or with inflation. To address these issues, we recommend the Legislature base income eligibility on the “income limits” published each year by the Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD). Based on data from the federal government, HCD publishes county‑level thresholds for households of different sizes that fall into three categories: low income (80 percent of median income in the county), very low income (50 percent of median income), and extremely low income (60 percent of very low income). The Legislature could choose among the different HCD income limits for eligibility depending on whether it wished to expand eligibility to households at higher income levels or keep eligibility at a roughly similar level. Specifically, the Legislature could choose to target income limits of:

- Very Low Income. To keep eligibility roughly similar, the Legislature would use “very low income” as the threshold. For example, in Sacramento County, which has an area median income near the state average, a household of four is designated as very low income if it has an income less than $40,000 (the same threshold for a family of two is $32,000).

- Low Income. To expand eligibility to households at higher levels of income, the Legislature could use “low income” as the threshold. For example, a household of four in Sacramento County is considered low income if its earnings fall below $64,000 ($51,000 for a family of two).

Using one of these thresholds, rather than a set dollar amount, would address all of the shortcomings of the income threshold identified in our evaluation.

Consider Expanding Eligibility by Lowering Age Requirements. Earlier, we discussed why lower‑income homeowners who are younger than 62 could potentially benefit from the PTP Program. In particular, Figure 4 showed that low‑income homeowners in their 40s and 50s spend the highest shares of their income on property taxes, which makes it more likely that they could face short‑term cash flow issues. For example, younger homeowners facing unemployment as a result of injury or job loss could benefit from the PTP Program. The Legislature could expand eligibility to those younger than 62 by setting a different age threshold—say, 40—or by eliminating the age requirements entirely.

Legislative Options to Lower Age Requirements. The Constitution only authorizes the Legislature to operate a property tax postponement program for homeowners who are blind, disabled, or over the age of 62. As such, the Legislature has two options to expand lower age requirements for the program. First, the Legislature could place a constitutional amendment before voters to change eligibility. Second, the Legislature could change the administration of PTP to reimburse homeowners directly, similar to the PTAP program (which did not require constitutional authorization). Changing the administration of the program in this way would mean PTP would not be a property tax exemption. This latter option has some drawbacks. In particular, it likely would mean higher administrative costs for SCO to issue checks for each approved applicant. Also, depending on how the program was constructed, it could result in some cash flow issues for homeowners, who might still need to first pay their property tax payments to the county and would then apply for reimbursement from the state.

Improve Affordability, But Limit State Risk

Lower the Interest Rate and Eliminate General Fund Sweep. For reasons we discussed earlier, the program’s interest rate of 7 percent is high. The high interest rate, coupled with the sweeping of fund balances above $15 million to the General Fund, means PTP provides a General Fund benefit to taxpayers. To address these problems, we recommend the Legislature eliminate the General Fund sweep and lower the interest rate. In particular, to account for variations in the interest rate environment over time, the Legislature could allow the rate to vary—for example, by linking it with earnings in the Pooled Money Investment Account. Historical data from the program suggests that PTP’s historical interest rate was adequate to cover administrative costs and state losses from delinquencies.

Couple Changes to Eligibility With Options to Limit State Risk. If the Legislature expands eligibility in the program, as we outline above, the changes could mean higher state costs from uncollectable loans. For example, allowing younger homeowners to participate could increase the risk that the total amount of deferment (the size of the loan) exceeded the value of the equity held in the home. This is because, compared to older homeowners, younger homeowners typically hold less equity and live longer. To address this and other risks, the Legislature could consider coupling changes to eligibility with changes to other program features that address costs and limit state risk. In particular, the Legislature could consider changes to:

- Interest Rate. The interest rate is the major mechanism the state can use to cover its costs (and therefore keep the program cost neutral to taxpayers). While the current rate is too high, depending on the extent of changes made to eligibility, the Legislature may want to lower the interest rate less than it would otherwise (if the program were not expanded).

- Total Amount of Deferment. The Legislature could limit the total amount of PTP deferment to the estimated value of equity a homeowner holds in the home. This is, in practice, what SCO already does with existing applicants, but the requirement is not statutory. To mitigate state risk even further, the Legislature could set this threshold lower, for example, to 90 percent of the estimated value of equity held by the homeowner.

- Number of Years of Participation. Another option to limit state risk is to limit the number of years a younger homeowner is allowed to participate in the program. For example, the Legislature could limit those under the age of 62 from accessing the program for more than, say, five years, but place no limit on those older than 62.