LAO Contact

January 14, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget:

Overview of the Governor's Budget

Executive Summary

Budget Position Continues to Be Positive. In our November Fiscal Outlook publication, we noted that the budget is in remarkably good shape—a comment based in large part on the significant discretionary resources we estimated were available. The Governor’s budget proposal reflects a budget situation that is even better than our estimates. Largely as a result of lower‑than‑expected spending in health and human services programs, we estimate the administration had nearly $20.6 billion in available discretionary resources to allocate. That said, recent financial market volatility poses some downside risk for revenues.

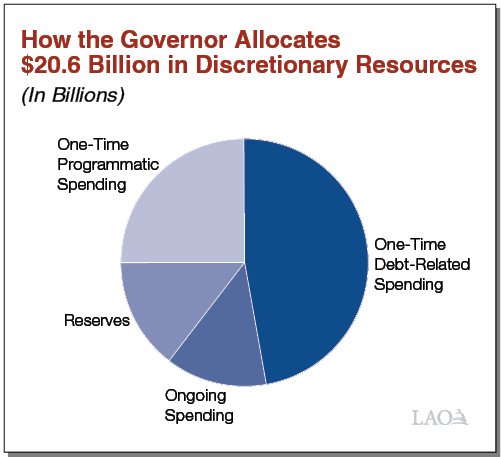

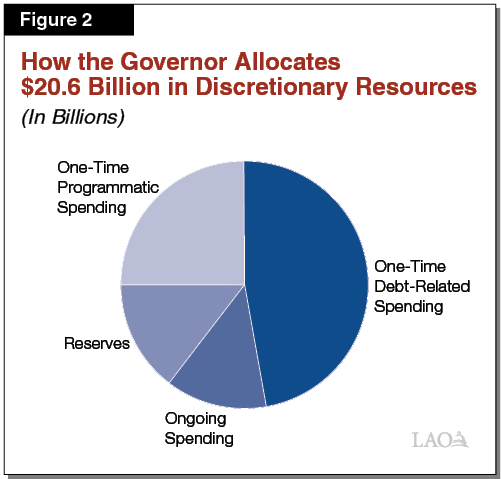

Governor’s Budget Prioritizes Debt Repayments and One‑Time Spending. The figure shows how the Governor proposes allocating the nearly $20.6 billion in available discretionary resources. The Governor proposes spending nearly half of these resources, $9.7 billion, to pay down certain state liabilities, including unfunded retirement liabilities and budgetary debts. The Governor allocates $5.1 billion—25 percent—to one‑time or temporary programmatic spending. The Governor allocates $3 billion—15 percent—to discretionary reserves. Although this represents a smaller share of resources than other recent budgets have devoted to reserves, the Governor’s decision to use a significant share of resources to pay down state debts is prudent.

Ongoing Costs Are in Line With Estimates of Available Ongoing Resources, but Costs Could Grow. The Governor proposes spending roughly $3 billion on an ongoing basis, which is a significantly higher level than recent budgets have allocated. Our economic growth scenario in the November Fiscal Outlook indicated $3 billion was roughly the level of ongoing spending that the budget could support. This was just one scenario, however, and some ongoing proposals would have higher costs under different economic conditions.

Governor’s Budget Outlines Many Policy Priorities Early. The Governor’s budget establishes a number of priorities for 2019‑20 and beyond, many of which align with recent legislative actions. In many cases, the administration is still developing these proposals and some are not yet reflected in the budget’s bottom line. By proposing these ideas at the beginning of the budget process, the Governor gives the Legislature the opportunity to collaborate with the administration to shape these policies.

On January 10, 2019, Governor Newsom presented his first state budget proposal to the Legislature. In this report, we provide a brief summary of the Governor’s proposed budget, primarily focusing on the state’s General Fund—the budget’s main operating account. (In the coming weeks, we will analyze the plan in more detail and release several additional budget reports.) We begin with an overview of the big picture budget condition under the Governor’s estimates and proposals. Then we describe the Governor’s major policy proposals in greater detail and provide our initial comments.

The Big Picture

This section provides an overview of the state budget’s condition under the Governor’s proposal. First, we discuss the General Fund’s bottom line condition under the administration’s assumptions, estimates, and proposals. Second, we discuss how the Governor chooses to allocate discretionary General Fund resources in the proposed budget. In short, the Governor’s budget proposes a total reserve level of $18.5 billion and allocates $20.6 billion in discretionary resources among a variety of priorities, primarily focusing on one‑time spending and debt repayments.

Budget Bottom Line

Revenues Grow to $142.6 Billion in 2019‑20. Figure 1 shows the General Fund condition under the administration’s estimates and assumptions. Over the three year period, revenues (excluding transfers) grow from $135.9 billion in 2017‑18 to $146.1 billion in 2019‑20 (3.7 percent average annual growth). Relative to estimates in the 2018‑19 Budget Act, the Governor’s budget assumes revenues in 2017‑18 and 2018‑19 will be $5.7 billion higher. From 2018‑19 to 2019‑20, the Governor estimates revenues will grow $5.1 billion (3.6 percent).

Figure 1

General Fund Condition Under Administration’s Estimates

(In Millions)

|

2017‑18 Revised |

2018‑19 Revised |

2019‑20 Proposed |

|

|

Prior‑year fund balance |

$5,582 |

$12,377 |

$5,241 |

|

Revenues and transfers |

131,495 |

136,945 |

142,618 |

|

Expenditures |

124,699 |

144,082 |

144,192 |

|

Ending fund balance |

$12,377 |

$5,241 |

$3,667 |

|

Encumbrances |

1,385 |

1,385 |

1,385 |

|

SFEU balance |

10,992 |

3,856 |

2,282 |

|

Reserves |

|||

|

SFEU balance |

$10,992 |

$3,856 |

$2,282 |

|

Safety Net Reserve |

— |

900 |

900 |

|

BSA balance |

10,798 |

13,535 |

15,302 |

|

Total Reserves |

$21,790 |

$18,291 |

$18,484 |

|

SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (discretionary reserve) and BSA = Budget Stabilization Account (constitutional reserve). |

|||

Spending Grows to $144.2 Billion in 2019‑20. Over the three year period, spending under the Governor’s plan grows from $124.7 billion in 2017‑18 to $144.2 billion in 2019‑20 (7.5 percent average annual growth). Spending remains flat between 2018‑19 and 2019‑20 (growing about one‑tenth of a percent) mostly because the Governor attributes at least $7 billion in certain debt repayment proposals to the current year. Otherwise, spending would be higher in 2019‑20. Under the administration’s estimates, constitutionally required General Fund spending on schools and community colleges is $55.3 billion in 2019‑20. The nearby box describes overall school and community college spending in greater detail.

Estimates of the Proposition 98 Minimum Guarantee Under Governor’s Budget

Guarantee Revised Down for Prior and Current Year, Projected to Grow Moderately in Budget Year. The minimum guarantee is the constitutionally required funding level for schools and community colleges and is met with a combination of General Fund and local property tax revenues. The Governor’s budget package contains the latest estimates of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee over the 2017‑18 through 2019‑20 period. Compared with June 2018 estimates, the minimum guarantee is down by $164 million in 2017‑18 and $526 million in 2018‑19. These revisions are mainly the result of student attendance coming in lower than the June estimates, coupled with the state’s 2017‑18 maintenance factor obligation being revised downward. Under the Governor’s budget, the 2019‑20 minimum guarantee is $80.7 billion, an increase of $2.8 billion (3.6 percent) over the revised 2018‑19 level. Separate from growth in the 2019‑20 guarantee, the Governor’s budget provides $687 million as a settle‑up payment related to meeting the minimum guarantee for years prior to 2017‑18.

Governor Proposes $18.5 Billion in Total Reserves in 2019‑20. Under the Governor’s proposed budget and revenue estimates, 2019‑20 would end with $18.5 billion in reserves. This would represent about 13 percent of General Fund revenues and transfers—higher than the enacted 2018‑19 level of 12 percent. The state’s budget reserves would have the following components:

- Budget Stabilization Account (BSA) Balance of $15.3 Billion. Under the Governor’s estimates and interpretation of the constitutional rules contained in Proposition 2 (2014), the state is required to make a $1.8 billion deposit into its constitutional reserve, the BSA. Under these estimates, the reserve would reach $15.3 billion at the end of 2019‑20.

- Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU) Balance of $2.3 Billion. The state’s other general purpose reserve account is the SFEU. Unlike the BSA, which has restrictions on its use of funds, the Legislature has discretion to use the funds in the SFEU at any time and for any purpose. The Governor proposes a year‑end balance in the SFEU of $2.3 billion, which is $321 million more than the enacted level of the fund in 2018‑19.

- Safety Net Reserve Increased to $900 Million. The Governor also proposes depositing an additional $700 million into the Safety Net Reserve in 2019‑20. The 2018‑19 budget package created this reserve to save money specifically for CalWORKs and Medi‑Cal. (During a recession, these programs typically have increased expenditures as caseload increases.) Including the $200 million deposit into the Safety Net Reserve enacted in 2018‑19, this proposed deposit would bring the total balance of the reserve to $900 million. The Governor proposes attributing this $700 million deposit to the 2018‑19 fiscal year, although the actual transfer likely would take place after June 30, 2019.

- No Deposit Into School’s Constitutional Reserve Required. In addition to the BSA, Proposition 2 established a specific statewide school reserve account (the Public School System Stabilization Account), which is governed by a separate set of formulas. To date, these formulas have not required any deposits being made into the school reserve. As with other recent budgets, this Governor’s budget does not include a deposit into the school stabilization account.

BSA Deposit Reflects Governor’s New Interpretation of Proposition 2. The Proposition 2 formulas require the state to set aside revenues, including those from capital gains, and use them to increase reserves and pay down certain state debts. Recent budgets also have made additional, optional deposits into the BSA above these requirements. When the BSA reaches 10 percent of General Fund taxes, additional funds required under the formulas must be spent on infrastructure. The 2018‑19 budget package anticipated the BSA would reach this constitutional threshold at the end of 2018‑19 and allocated future infrastructure spending requirements to specific purposes for three years. Under the new Governor’s interpretation of Proposition 2, however, optional deposits into the BSA do not count toward the 10 percent threshold level. Under the new administration’s estimates, mandatory BSA deposits represent 8.1 percent of General Fund taxes, which is below the constitutional threshold.

Discretionary Resources

Governor Allocates $20.6 Billion in the 2019‑20 Budget Process. We estimate that—after satisfying constitutional requirements, providing funds for caseload, price growth and new legislation, and adjusting program cost estimates—the Governor had $20.6 billion in discretionary resources available to allocate in the 2019‑20 budget process. In our November Fiscal Outlook report, we projected $14.8 billion would be available this year. There are three major components of this nearly $6 billion difference:

- Administration’s Revenues Are Higher by $500 Million. The administration’s revenue assumptions are very close to our November 2018 Fiscal Outlook revenue estimates. Across 2017‑18 to 2019‑20—before the effects of proposed policy changes—our estimates of General Fund revenues are lower than the administration’s by less than $100 million. The administration also proposes some changes to tax policy (described more later) which would raise an additional $400 million, on net, in 2019‑20.

- Administration’s Estimates of Medi‑Cal Spending Are Lower by Nearly $4 Billion. The administration revised prior estimates of spending on Medi‑Cal downward very significantly. From 2017‑18 to 2019‑20, its estimates of baseline Medi‑Cal expenditures (before accounting for policy changes) is $3.8 billion lower than we estimated in November. This difference includes a roughly $2 billion downward revision to current‑year expenditures. The administration attributes much of this difference to funding shifts and other complex financing mechanisms. In fact, significant current‑year revisions to the Medi‑Cal program have become common in recent years—although they often occurred in the other direction.

- Administration’s Estimates of IHSS and SSI/SSP Spending Lower by Over $400 Million. The administration’s estimates of programmatic spending on the In‑Home Supportive Services (IHSS) and Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Payment (SSI/SSP) programs is lower than our November estimates by over $400 million across 2018‑19 and 2019‑20. (This excludes policy changes that raise costs in both programs in 2019‑20.) In the case of IHSS, these reduced costs are largely related to slower growth in caseload and cost per case. In SSI/SSP, these reduced costs are primarily due to lower‑than‑expected caseload and a technical change to current year spending.

Governor Allocates Most Discretionary Resources Toward One‑Time Spending in 2019‑20. Figure 2 shows how the Governor proposes to allocate the $20.6 billion in discretionary resources among spending and reserves. As the figure shows, the Governor allocates most of these resources to spending on a one‑time basis, both for programmatic expansions and to repay various state debts and liabilities. We summarize these allocations below. In the next section, we describe and comment on some of the major proposals.

- $9.7 Billion One Time to Reduce Debts and Liabilities. The Governor proposes spending almost half of discretionary resources—$9.7 billion—to pay down certain state liabilities on a one‑time basis. (This total excludes required debt payments under Proposition 2.) The administration attributes most of these debt repayments to fiscal year 2018‑19. The nearby box describes these proposals in more detail.

- $5.1 Billion to One‑Time Programmatic Spending. The Governor proposes spending about a quarter of discretionary resources, or $5.1 billion, on a one‑time or temporary basis for a variety of programmatic expansions. The largest proposals include $1.3 billion for housing production and $750 million for expanding kindergarten facilities.

- $3 Billion to Reserves. The Governor commits $3 billion (15 percent) of discretionary resources to reserves—the SFEU and the Safety Net Reserve. (This excludes the $1.8 billion BSA deposit, which we do not include as discretionary because of the administration’s new Proposition 2 interpretation.)

- $2.7 Billion to Ongoing Spending. The Governor’s spending proposals also include $2.7 billion in ongoing spending, representing a bit more than 10 percent of resources available. Some of the largest of these proposals include nearly $350 million to increase CalWORKs grant levels, $300 million for California State University (CSU), $240 million for University of California (UC), and $125 million to fund additional full‑day state preschool slots. Because some of these ongoing proposals are phased in over a multiyear period, we estimate the cost at full implementation of all of these proposals is $3.5 billion.

The Governor’s Proposed Pay Down of Debt and Liabilities

Governor Pays Down $5.3 Billion in Unfunded Pension Liabilities. Both CalPERS and CalSTRS have significant unfunded liabilities: $59 billion for CalPERS and $104 billion for CalSTRS (roughly one‑third of this is considered the state’s share and about two‑thirds is attributed to school districts and community colleges). In addition to required annual contributions, the Governor proposes that the state make supplemental contributions from the General Fund to the pension systems to reduce the unfunded liabilities and reduce state costs over the next few decades. Specifically:

- $3 Billion Toward the State’s CalPERS Unfunded Liability. The administration plans to introduce trailer bill language that would make a $3 billion supplemental payment to CalPERS in 2018‑19.

- $2.3 Billion Toward Districts’ Share of CalSTRS Unfunded Liability. To reduce the districts’ share of the CalSTRS unfunded liability, the Governor proposes the state pay CalSTRS an additional $2.3 billion, also attributed to 2018‑19.

Governor Repays $4.4 Billion in Budgetary Liabilities. In addition to retirement liabilities, the state has a number of budgetary liabilities. Generally, these are debts the state incurred in the last decade to address its budget problems. The Governor proposes repaying:

- $2.1 Billion for Special Fund Loans. During the Great Recession, the state loaned amounts to the General Fund from other state accounts known as special funds. The prior administration had a multiyear plan to repay these loans using Proposition 2 debt payment requirements. The new administration proposes repaying all remaining special fund loans this year and does not attribute them to Proposition 2.

- $1.7 Billion to Undo Payment Deferrals. The administration also proposes undoing two budgetary payment deferrals. The first is a one‑month deferral of state employee payroll from June to July and the second is a fourth‑quarter deferral to CalPERS.

- $687 Million for Settle Up. Required General Fund spending for schools and community colleges in any given fiscal year is based on numerous factors, including General Fund tax revenue and per capita personal income. Estimates of these factors often change after the level of funding is set in the budget. Sometimes the actual requirement turns out to be larger than the budgeted amount, meaning the state owes additional amounts—“settle up.” The Governor proposes repaying the outstanding settle up obligation of $687 million. (Typically, the administration reflects settle‑up payments in the entering fund balance, however, only a portion of this $687 million planned payment is reflected there. Based on the information we have to date, this may mean the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties balance is $475 million lower than currently estimated.)

Governor Restructures Proposition 2 Plan to Pay Down State’s Share of CalSTRS Unfunded Liability. By paying down all remaining special fund loans with discretionary resources, the new administration has additional capacity within Proposition 2 requirements for other debt payments. The Governor proposes using this new capacity to reduce the state’s share of the CalSTRS unfunded liability. Specifically, the Governor proposes to pay an additional $1.1 billion to CalSTRS in 2019‑20. Over the next few years, the administration anticipates an additional $1.8 billion would be paid to CalSTRS using these debt payments. That said, Proposition 2 requirements vary with economic and financial market conditions, which could result in higher or lower payments than anticipated.

Other Policy Plans

In addition to these budget proposals which carry costs in 2019‑20 and beyond, the Governor introduces a few policy goals with notable budgetary implications. Because these proposals are still in development, they largely are not included in the administration’s budget bottom line. In particular, the Governor proposes: (1) funding a work group to develop a plan for implementing universal preschool, (2) directing the Department of Health Care Services to negotiate prescription drug prices on behalf of all Medi‑Cal beneficiaries (and commits to reviewing existing state prescription drug negotiation and procurement practices), and (3) expanding paid family leave. In the case of universal preschool and paid family leave, the Governor notes the policies also would need to be accompanied with a new revenue source to fully fund the new programs.

LAO Comments

Revenues

Revenues Estimates In Line With Our November Outlook, but Financial Market Poses Risk. The administration’s revenue assumptions are very close to our November 2018 Fiscal Outlook revenue estimates. Across 2017‑18 to 2019‑20—before the effects of proposed policy changes—our November estimates of General Fund revenues are lower than the administration’s by less than $100 million. This difference is very small in budgetary terms. That said, stock prices fell sharply at the end of 2018 and currently sit more than 10 percent below their September peak. Both our and the administration’s estimates were developed before the full scope of this decline was realized. As a result, capital gains revenues likely will be lower than the Governor’s budget assumes unless stock prices grow significantly in the coming months. Our review of historical stock performance suggests that the required growth in stock prices needed to meet revenue estimates occurred in 29 of the last 70 years. If stock prices instead grow modestly in 2019—as suggested by the December consensus forecast of professional economists compiled by Moody’s Analytics—capital gains revenues are likely to fall below expectations by $1 billion to $2 billion.

Some Losses in Capital Gains Revenues Would Be Offset by Lower Constitutional Spending Requirements. In isolation, the financial market experience at the end of 2018 suggests there could be downside risk for the budget in the May Revision. This would be different than recent years in which the Legislature has had more—rather than less—resources available to allocate in May. That said, a decline of $1 billion to $2 billion in capital gains revenues would be offset—likely in large part—by lower constitutionally required spending and reserve deposits. As a result, under current conditions, the net effect on discretionary resources would be less than the full revenue decline. Current financial market and economic conditions can change significantly between now and May, however, leading to greater revenue effects.

Budget Condition

Budget Position Continues to Be Positive. In November, we noted that the budget is in remarkably good shape—a comment based in large part on the significant discretionary resources we estimated were available. The Governor’s budget proposal reflects a budget situation that is even better than our estimates, mostly due to lower‑than‑expected spending in health and human services programs.

Administration Allocates Smaller Share of Available Resources to Reserves, but Takes Other Actions to Improve Budget’s Multiyear Condition. Reserves are the most important tool that the Legislature has to address a budget problem during a recession. The Governor takes an interpretation of Proposition 2 that requires a higher reserve deposit into the BSA. But, in percentage terms, the 2019‑20 proposed allocation to reserves is low compared to recent years. The Governor takes other actions, however, to improve the budget’s bottom line condition. In particular, the Governor focuses most of his spending proposals on one‑time purposes and uses a significant portion of discretionary resources to pay down debts and liabilities. Doing so benefits the budget in future years and in some cases reduces ongoing spending growth.

Administration’s Interpretation of Proposition 2 Eliminates Planned Infrastructure Spending. The 2018‑19 budget package anticipated the BSA would reach its constitutional threshold of 10 percent of General Fund taxes, triggering required spending on infrastructure. Budget trailer language appropriated these future, anticipated spending requirements for three purposes: (1) state infrastructure, (2) rail infrastructure, and (3) affordable housing. Had the new administration maintained the prior interpretation of Proposition 2, it would have been required to dedicate $415 million to fund state infrastructure, $173 million to rail infrastructure, and $173 million to affordable housing.

Ongoing Costs Are in Line With Estimates of Available Ongoing Resources, but Costs Could Grow. The Governor’s ongoing spending proposals total $2.7 billion in 2019‑20, but these costs grow over time, reaching an estimated $3.5 billion under full implementation. These expenditure levels are roughly in line with our assumptions in our November Fiscal Outlook economic growth scenario. Under our assumptions in this scenario, we found the state budget could have the capacity to take on about $3 billion in ongoing commitments without creating an operating shortfall. That said, there are sources of uncertainty in these proposals not captured in these estimates. For instance, in a recession, the Governor’s proposal to increase CalWORKs grant levels would increase in cost. Another risk is the cost of disaster mitigation, response, and recovery. While the Governor’s budget includes mostly one‑time spending for these purposes, they are more likely to be ongoing costs.

Schools Could Be Vulnerable to a Recession. State school funding might be relatively vulnerable to a recession for two reasons. First, the state has made no deposit to date in the school stabilization account. In the event of a recession, this could result in pressure to use BSA withdrawals for schools. Second, the Governor’s budget includes no one‑time spending proposals inside the 2019‑20 Proposition 98 minimum guarantee to mitigate the effects of a future drop in the guarantee. In each of the past six years, the state has purposefully provided such a cushion. From 2013‑14 through 2018‑19, the state set aside an average of about $700 million per year inside the guarantee for one‑time purposes. This one‑time spending provides a buffer that reduces the likelihood of cuts to ongoing programs if the guarantee experiences a year‑over‑year decline. The Governor’s budget not only has no such cushion, it supports roughly $100 million ongoing program costs with one‑time funding, leaving a small ongoing shortfall in the 2020‑21 budget.

Key Budget Proposals

This section describes and provides our initial assessment of the major General Fund budget proposals included the Governor’s January budget, including both discretionary and nondiscretionary spending amounts. Figure 3 lists the Governor’s major discretionary budget proposals for programmatic spending (while all of these are currently proposed, most are attributed to 2019‑20, but some to 2018‑19).

Figure 3

Major Discretionary General Fund Programmatic Spending Proposals in Governor’s Budget

(In Millions)

|

One‑Time or Temporary |

Ongoing Amount |

|

|

Education |

||

|

Provides funding to support full‑day kindergarten, including facilities |

$750 |

— |

|

Expands child care facilities and provides workforce education |

500 |

— |

|

Pays a portion of school districts’ pension costs |

350 |

— |

|

Provides various augmentations to UC |

153 |

$240 |

|

Provides various augmentations to CSU |

264 |

300 |

|

Other education proposals |

32 |

258 |

|

Health and Human Services |

||

|

Increases CalWORKs grant payments by 13.1 percent across the board |

— |

348 |

|

Continues the 7 percent service hour restoration in IHSS |

— |

342 |

|

Revises the county IHSS share of costs |

— |

242 |

|

Ends General Fund offset of Medi‑Cal spending using Proposition 56 |

— |

218 |

|

Extends full scope Medi‑Cal benefits to young adults regardless of immigration status |

— |

134 |

|

Other health proposals |

77 |

34 |

|

Other human services proposals |

148 |

219 |

|

Housing and Homelessness |

||

|

Provides grants to local governments to increase housing production |

750 |

— |

|

Proposes various initiatives to address homelessness |

600 |

25 |

|

Expands the Mixed‑Income Loan Program |

500 |

— |

|

Disaster‑Related |

||

|

Waives counties’ share of debris removal costs from recent wildfires |

155 |

— |

|

Provides various augmentations to OES |

146 |

36 |

|

Provides various augmentations to CalFire |

18 |

87 |

|

Criminal Justice |

||

|

Provides various augmentations for the Judicial Branch |

155 |

56 |

|

Provides various augmentations for CDCR |

44 |

53 |

|

Other criminal justice proposals |

16 |

117 |

|

Other |

||

|

Addresses deferred maintenance across various departmentsa |

134 |

— |

|

Other proposals |

339 |

10 |

|

Total, Programmatic Spending |

$5,132 |

$2,718 |

|

aExcludes some deferred maintenance proposals that are included in departments listed elsewhere. Note: Excludes spending on K‑14 education, reserves, and debt (required by the California Constitution), and added costs to maintain existing policies. Figure also excludes some smaller spending proposals. FPL = federal poverty level; IHSS = In‑Home Supportive Services; OES = Office of Emergency Services; CalFire = California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection; and CDCR = California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. |

||

Education

Early Education

Expanding Preschool Beginning With Low‑Income Students Is a Reasonable, Needs‑Based Approach. The budget includes $125 million (non‑Proposition 98 General Fund) ongoing to provide 10,000 full‑day preschool slots for children from low‑income families. The funding is to be the first of three augmentations, with the intent to provide a total of 30,000 additional slots to serve all low‑income four‑year olds by 2021‑22. These slots would be on top of the almost 9,000 full‑day slots the state added over the past three years. Extending preschool to all children from low‑income families is consistent with considerable research that has concluded the benefits of preschool are greatest for these children. Even though we believe the Governor’s overall preschool expansion is reasonable, the Legislature likely will want to consider the implementation details. Timing; outreach to families; and any changes to program eligibility, contracting, and accountability will be particularly important issues to consider.

Other Early Education Proposals Largely Placeholders, Offer Legislature Opportunity to Set Its Priorities. The Governor’s budget also includes $750 million (non‑Proposition 98 General Fund) one time to create more full‑day kindergarten programs. The funds are primarily intended for constructing new or retrofitting existing school facilities needed to operate the longer‑day programs. Additionally, the Governor’s budget includes a total of $500 million for improvements to early education ($245 million for facilities, $245 million for the child care workforce, and $10 million for a comprehensive plan to improve access and quality). At this time, the administration has few details on how these funding amounts would be allocated or used. Given the large dollar amounts at stake, we encourage the Legislature to think about its priorities across the state budget. If the Legislature were to decide to use one‑time funds in the early education area, it could continue to focus on facility and/or workforce issues, as these have long been areas of concern for the field. The Legislature, however, might consider more targeted initiatives linked with specific goals. For example, it could link any one‑time workforce funding to helping with a transition to a new child care reimbursement rate system and/or higher minimum program standards.

Schools and Community Colleges

New Administration Maintains Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), Providing Continuity for Districts. Even though LCFF was a key reform initiated by the prior administration, the new administration continues to fund it. The largest Proposition 98 augmentation in the Governor’s budget is $2 billion for LCFF, which covers a 3.46 percent cost‑of‑living adjustment. The Governor’s budget also includes a few augmentations designed to improve support for districts not meeting the goals of their Local Control and Accountability Plans (LCAP)—another linchpin reform of the prior administration. The 2019‑20 package of budget proposals seems to signal the new administration’s willingness to support the LCFF and LCAP systems. Such continuity could be of significant benefit to districts as they budget, build their strategic academic plans, identify their performance problems, and access support to address those problems.

Special Education Proposal Unlikely to Promote Early Intervention Programs. The budget provides a total of $577 million ($390 million ongoing and $187 million one time) to districts based on their unduplicated counts of low‑income students, English learners, and students with disabilities they serve. The administration indicates schools may use these funds for either (1) special education services for students with disabilities or (2) early intervention programs for students who are not yet receiving special education services. Because special education costs have far outpaced special education funding in recent years, most schools receiving funding under the Governor’s proposal likely would use the funds to help them cover their existing special education costs. If the Legislature wanted to promote early intervention programs, it likely would need to take a different approach—crafting a more targeted initiative with specific requirements and accountability measures. As a targeted early intervention program likely could benefit many students and keep some students from later needing more expensive special educations services, the Legislature will want to think carefully about which of the Governor’s two goals it would most like to address.

CalSTRS Budget Relief Proposal Raises Near‑ and Long‑Term Trade‑Off. Separate from his proposals to pay down the CalSTRS unfunded liability, the Governor proposes providing $700 million over the next two years ($350 million per year) to provide school and community college districts immediate budget relief. Specifically, the funds would reduce districts’ CalSTRS rates in 2019‑20 and 2020‑21—freeing up resources for other parts of districts’ operating budgets. Though district pension costs typically are covered using Proposition 98 General Fund, the Governor proposes using non‑Proposition 98 General Fund for this proposal. Whereas this proposal would provide districts with perceptible budget relief over the next two years, using the $700 million instead for paying down more of the CalSTRS unfunded liability would provide a longer‑term benefit. Although over the long term the districts’ CalSTRS rate would be only slightly lower than it would be otherwise, the value of a making a $700 million unfunded liability payment now would grow over time. Such future relief could be important during the next economic downturn.

Higher Education

Provides Universities Large, Ongoing Augmentations Dedicated to Specific Purposes. The Governor’s budget includes an increase of $540 million ongoing General Fund for the universities—$300 million (7.6 percent) for CSU and $240 million (6.9 percent) for UC. Whereas the previous Governor favored giving the universities unrestricted increases and allowing them to determine funding priorities, the new administration takes a different approach by itemizing proposed funding increases. Specifically, for CSU, the augmentation is intended to cover increases in compensation, the Graduation Initiative, and enrollment. (The budget for CSU includes an additional $64 million ongoing to cover higher retiree health benefit and pension costs.) For UC, $200 million of its ongoing augmentation is intended to cover increases in operating costs (including some employee compensation costs), student success initiatives, student hunger and housing initiatives, mental health services, and 2018‑19 enrollment. (For both segments, the Governor links the proposed General Fund augmentation with an expectation that tuition for resident students not be increased in 2019‑20.) Centering the university budgets around explicit funding priorities likely will foster more productive budget conversations and enhance fiscal accountability.

Proposes Two Cal Grant Policy Changes, Mostly Consistent With Recent Legislative Priorities. The Governor proposes $122 million for greater living assistance for California Community Colleges, CSU, and UC Cal Grant recipients who have dependent children. The Governor also proposes $9.6 million to fund an additional 4,250 Cal Grant competitive awards, which would raise the total number of new competitive awards authorized annually to 30,000. Over the past several years, the Legislature has focused on certain financial aid goals, including: (1) increasing living assistance (especially for students enrolled full time); (2) expanding the number of Cal Grant competitive awards, as demand currently greatly exceeds supply; and (3) simplifying the state’s financial aid system. Although the Governor’s proposals would advance the first two of these goals, his living assistance proposal could complicate rather than simplify the state’s financial aid system. By applying only to Cal Grant recipients with children rather than to all Cal Grant recipients, the Governor’s proposal adds new program rules that could make understanding and navigating the financial aid system more difficult for students.

Health and Human Services (HHS)

Health Care Coverage

Extends Full‑Scope Medi‑Cal Coverage to Income‑Eligible Young Adults Regardless of Immigration Status. The Governor’s budget proposes to extend full‑scope Medi‑Cal coverage to all young adults ages 19 through 25 regardless of immigration status. Most of these individuals do not have full health insurance coverage. The administration estimates this would extend health care coverage to 138,000 undocumented immigrants and would cost $134 million General Fund in 2019‑20. Estimates suggest the current number of uninsured Californians—including those who are undocumented—is roughly 3.5 million.

Budget Does Not Assume Renewal of Managed Care Organization (MCO) Tax, Foregoing a Potential General Fund Benefit. Since 2016‑17, the state has imposed a tax on MCOs that—when combined with a package of associated tax changes—generates a net General Fund benefit of over $1 billion by drawing on additional federal funds. Under state law, the MCO tax expires at the end of 2018‑19. Extending the MCO tax past 2018‑19 would require statutory reauthorization from the Legislature and approval from the federal government. Based on the recent federal approval of a similar tax in Michigan, federal approval of a reauthorized California MCO tax appears likely. Despite this development, the administration did not propose an extension of the MCO tax in 2019‑20, forgoing over $1 billion in General Fund benefit.

Proposal to Fund Covered California Subsidies With New Health Coverage Mandate Revenues Raises Issues. The federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act sought to reduce the number of people without health insurance coverage in part by imposing a financial penalty on those without health insurance (known as the “individual mandate”). In 2017, Congress passed legislation that reduced the amount of the individual mandate penalty to zero, effectively making the mandate unenforceable. This change is expected to result in some—likely healthier—individuals dropping their health insurance coverage, leading to higher premiums. To encourage individuals to maintain coverage and avoid potential premium increases, the Governor proposes creating a state individual mandate modeled after the original federal mandate. The Governor further proposes to use the revenues from the mandate to pay for additional subsidies for those who purchase health insurance through Covered California. These state subsidies would supplement federal subsidies already available to some households and would provide new subsidies to some relatively higher‑income households that currently do not currently qualify.

The Governor’s proposal raises a few issues for consideration:

- Dedicating Penalty Revenues to Fund Subsidies Creates Conflicting Goals. The goal of a penalty associated with the individual mandate is to encourage people to enroll in insurance coverage. The penalty is effective if more households gain or maintain coverage. Consequently, penalty revenue should decline over time. The Governor, however, uses the individual mandate revenue to fund state health insurance subsidies. If the state penalty is effective and subsidy revenue declines, less funding would be available for premium subsidies. One alternative would be to use General Fund revenues to cover subsidy costs.

- Mandate Penalty and Subsidies Could Be Structured in Various Ways. Should the Legislature proceed with the concept of a state individual mandate and state insurance subsidies, it will face various choices related to the structure of both the state subsidies and the individual mandate. For example, depending on its priorities, the Legislature could focus on increasing assistance for relatively lower‑income households that already receive federal subsidies. The Legislature also could depart from the structure of the federal individual mandate penalty, for example, by allowing penalty amounts to vary with a household’s income in a different way.

- Multiple Tools Available to Encourage People to Maintain Coverage and Mitigate Cost Increases. If the Legislature is concerned that the elimination of the federal penalty will reduce health care coverage in California and increase premiums, there are other policies the state could consider. For instance, to increase the proportion of individuals with health insurance coverage, uninsured individuals could be automatically enrolled into health plans. To mitigate premium cost increases, the state could subsidize health insurers’ costs for high‑risk (high‑cost) individuals. Alternatively, the state could take action to increase competition among insurers participating in Covered California.

Other Major HHS Proposals

Proposed CalWORKs Grant Increase Reflects Step Toward Legislature’s Goal. The 2018‑19 budget package included statutory intent language stating the Legislature’s goal to increase CalWORKs grants to ensure participating families’ incomes are above 50 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) by 2020‑21. The 2018‑19 budget approved the first step of this plan by providing an across‑the‑board 10 percent grant increase effective April 1, 2019. The Governor’s budget proposes to further increase CalWORKs grants by 13.1 percent, which would raise grant levels to 50 percent of FPL for a family of three. The proposal assumes the grant increase would go into effect October 1, 2019 and cost $348 million in 2019‑20. Full‑year costs are expected to be $455 million in 2020‑21. The administration’s proposal differs from the Legislature’s plan both in terms of the grant amount and the timing. Specifically, the Governor’s target for 2019‑20 is based on a narrower definition of family size (only CalWORKs‑eligible family members are counted) than the target in the Legislature’s plan—resulting in a smaller grant increase—and would take effect six months earlier than the Legislature’s plan.

Continues Funding for 7 Percent IHSS Service‑Hour Restoration. Since 2016‑17, the General Fund has supported the restoration of IHSS service hours, which were previously reduced by 7 percent, as long as the MCO tax is in place. Although the budget does not assume an extension of the MCO tax, it does propose the continued use of General Fund for the 7 percent restoration in 2019‑20. The cost of the 7 percent restoration is estimated to be $342.3 million in 2019‑20. While the administration is not proposing to eliminate the current statutory language that ties the 7 percent restoration to the existence of the MCO tax, we understand the administration intends for the restoration of IHSS service hours to be ongoing.

Shifts Some County IHSS Costs to General Fund, Potentially Addressing Some State‑County Cost‑Sharing Issues. The budget proposes a number of changes to the mechanism by which the state provides counties with funding for IHSS costs. These changes aim to address some of the shortcomings of the existing cost‑sharing structure, but counties likely would have unmet costs in future years. The budget also proposes changes to counties’ share of cost for locally established wages and how certain funds for social services and health programs are allocated. On net, these various proposals increase General Fund costs by $241.7 million in 2019‑20. These costs will increase substantially over time. Under current estimates, they will reach nearly $550 million in 2022‑23.

Housing and Homelessness

Governor Proposes $1.3 Billion (One Time) Aimed at Increasing Housing Production. The Governor’s budget includes two proposals aimed at increasing housing production. One is a grant to local governments; the other expands an existing loan program.

- Grants to Local Governments. The Governor proposes $750 million in General Fund grants to local governments meant to accelerate meeting new housing production goals (to be developed by the Department of Housing and Community Development). Of this amount, $250 million could support various local government activities, like conducting planning and making zoning changes. As local governments reach these new goals, an additional $500 million would be available to cities and counties for general purposes.

- Middle‑Income Housing Loans. The Governor’s budget proposes $500 million General Fund to expand the California Housing Finance Agency’s (CalHFA’s) Mixed‑Income Loan Program. (This is in addition to the $43 million allocated for the program in the budget with revenue from the recent real estate document recording fee.) The program provides loans to developers for housing developments that include housing for low‑ to middle‑income households.

Additionally, the budget proposes expanding the state’s housing tax credit program by $500 million. Of this amount, $300 million would be allocated to the state’s existing low‑income housing tax credit program, which provides funding to builders of low‑income affordable housing. The remaining $200 million would be allocated to a new program targeting housing development for households with higher‑income levels. However, the budget assumes no reduction in revenues due to the tax credit in 2019‑20 or in its multiyear budget plan, suggesting the administration believes that developers will not claim the tax credit in the budget year or the next few years.

Housing Proposals Raise Questions About Which Population to Prioritize. The number of low‑income Californians in need of housing assistance far exceeds the resources of existing federal, state, and local affordable housing programs. Recent housing assistance programs have allocated the majority of funding to housing targeted at low‑income Californians. The Governor’s housing proposals spread limited resources to broader income levels, including middle‑income Californians. The Legislature may want to consider whether it prefers to target the state’s limited housing resources toward the Californians most in need of housing assistance.

Governor Proposes $600 Million for Various Proposals to Address Homelessness. The Governor’s budget also includes a variety of proposals to address homelessness. Dedicating significant one‑time resources to homelessness is consistent with the 2018‑19 budget package, which included $500 million in local government grants for homelessness services.

- Regional Homelessness Planning. The Governor proposes $300 million General Fund in 2019‑20 for local governments to expand or develop emergency shelters, navigation centers, and supportive housing. The funding would be available to local governments that develop joint regional plans to address homelessness.

- Funding for Jurisdictions Meeting Shelter and Housing Development Milestones. The Governor proposes $200 million General Fund for local governments that show progress toward developing shelters and housing for the homeless.

- Funding for Whole Person Care (WPC) Pilot Programs. The state’s federal Medicaid waiver allows for local initiatives that coordinate health, behavioral health, and social services for Medi‑Cal beneficiaries. These programs have the option of providing housing and supportive services. The Governor’s budget proposes a one‑time $100 million General Fund grant to local governments for WPC pilots—with the funds available until July 2025—to fund housing and supportive services for individuals who are homeless or at risk of homelessness, focusing on individuals with mental illness.

Disaster Response and Recovery

Governor’s Plan for Disaster‑Related Activities. For 2018‑19, the budget assumes a net increase of $923 million will be needed from the General Fund for response and recovery activities associated with the Camp, Woolsey, and Hill fires that occurred in November 2018. This assumes that the federal government will reimburse the state for 75 percent of the state’s eligible costs associated with these wildfires (though the Governor's administration has requested the federal government reimburse the state for 100 percent of certain eligible costs, the administration has yet to receive a response). The Governor also proposes the state General Fund pay for the local share of debris removal costs associated with the fires, currently estimated at $155 million. In addition, the administration indicates that it intends to request a total of $60 million from the General Fund in the coming months for a public education campaign ($50 million) and for the modernization of the 9‑1‑1 system ($10 million).

For 2019‑20, the Governor’s budget also includes a total of $555 million for a number of proposals in several departments related to disaster response and recovery (about one‑third of this is one time). Figure 4 summarizes the proposals for 2019‑20, which include:

- $359 Million for Other Wildfire Prevention and Response Activities. The budget includes $235 million to implement a package recent legislation related to wildfires. Of this amount, $200 million is from the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund for the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire) to complete forest thinning and forest health projects. The budget also includes $124 million, primarily from the General Fund, for other wildfire response‑related proposals, such as for additional CalFire fire engines ($40 million) and prepositioning of Office of Emergency Services and local fire engines ($25 million).

- $165 Million for Other Disaster‑Related Proposals. The budget includes $165 million in 2019‑20 for various disaster‑related proposals that are not specifically focused on wildfires. The largest share of this funding—$78 million across various departments from a combination of General Fund and special funds—is for improvements to the public safety radio system and to purchase additional radios. Other major proposals include $51 million (mostly General Fund) to modernize the 9‑1‑1 system, $20 million (General Fund) for public infrastructure and local emergency response costs through the California Disaster Assistance Act, and $16 million (General Fund) to continue the implementation of the state’s Earthquake Early Warning System.

- $31 Million to Backfill Property Taxes for Local Governments Affected by Recent Wildfires. The Governor’s budget provides $31 million from the General Fund in 2019‑20—to be expended over a few years—to backfill wildfire‑related property tax loses for cities, counties, and special districts associated with certain major wildfires that have occurred since 2015. Additionally, to the extent that schools and community colleges experience losses in local property tax revenues as a result of these fires, the state would automatically provide a corresponding backfill from Proposition 98 General Fund.

Figure 4

Summary of Governor’s Disaster‑Related Proposals for 2019‑20

(In Millions)

|

Proposals |

Amount |

|

Property Tax Backfill |

$31 |

|

Other Wildfire Prevention and Response |

|

|

Wildfire legislative packagea |

235 |

|

Other wildfire‑related proposals |

124 |

|

Subtotal |

($359) |

|

Other Disaster‑Related |

|

|

Public safety radio system |

$78 |

|

9‑1‑1 modernization |

51 |

|

California Disaster Assistance Act |

20 |

|

Earthquake Early Warning System |

16 |

|

Subtotal |

($165) |

|

Total |

$555 |

|

aLegislative package consists of Chapter 624 of 2018 (SB 1260, Jackson), Chapter 626 of 2018 (SB 901, Dodd), Chapter 635 of 2018 (AB 2126, Eggman), Chapter 637 of 2018 (AB 2518, Aguiar‑Curry), and Chapter 641 (AB 2911, Friedman). |

|

|

Note: Includes all fund sources. Excludes funding proposed for 2018‑19. |

|

Proposals Raise Several Issues for Legislative Consideration. These proposals present some trade‑offs. First, some proposals fund certain activities that have traditionally been funded from special funds—such as those related to the 9‑1‑1 system—from the General Fund. Second, the proposals include significantly more funding to assist local governments recovering from disasters than the state has provided in the past, such as for property tax backfills. The Legislature will want to consider how best to prioritize providing local governments with greater assistance while meeting other statewide priorities. Third, the Legislature might wish to consider whether the Governor’s decisions regarding the amount of funding provided to fire prevention (such as forest health) versus disaster response (such as fire engines) is consistent with its priorities.

Tax Policy Changes

Earned Income Tax Credit

Expands State Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). Working individuals and families with very low earnings (less than $24,950 in 2018) may claim a refundable tax credit when they file their state income tax returns. Last year, 1.5 million taxpayers received credits totaling $348 million. The administration proposes to expand the state EITC by making three changes: (1) providing an additional $500 credit per child under the age of six, (2) increasing the maximum qualifying income by about 20 percent, and (3) increasing the credit for individuals and families with earnings at the higher end of the eligibility range. The administration estimates these changes would increase the amount of credits received by $600 million—bringing total credits to around $1 billion—and increase the number of taxpayers receiving the credit by 400,000. The administration also proposes renaming the credit to the “Working Families Tax Credit.”

EITC Cost and Participation Changes Are Difficult to Estimate. While the proposed changes likely would increase the number of taxpayers who qualify for and receive the credit by several hundred thousand, it is difficult to estimate the extent of these increases with a high level of confidence. Outcomes of previous changes to the state EITC have deviated notably from the initial estimates. Given this, there is a good chance that the actual increase in the number of qualifying taxpayers and the total credit amount could be somewhat higher or lower than the administration’s estimate.

Conformity Changes

Conformity Simplifies Tax Administration, but Is Not Always in State’s Best Interest. The state usually incorporates many federal tax changes into state law. The state has yet to take action to conform to major changes to federal tax law passed in 2017. The administration proposes conforming to some of these changes that apply to businesses and has identified a list of potential conforming actions for the Legislature to consider. The administration’s intent is for the state to adopt a package of conforming changes that increases revenues by enough to cover the cost of their proposed expanded state EITC program—roughly $1 billion per year. While state tax laws are easier to comply with and administer when they follow federal laws—especially for definitions of the types of income subject to tax and of the types of expenses that can be deducted—some federal tax provisions may be inconsistent with state policy goals. In these cases, the state has to weigh the benefit of pursuing its own policy goals against the additional compliance and enforcement cost associated with deviating from federal law. The magnitude of these costs would vary depending on how the state chose to conform.

Conformity Changes and EITC Expansion Should Be Considered Separately. Attempting to offset revenue losses from an expanded state EITC through a package of conformity actions would be problematic. Estimates of the revenue impacts of expanding the state EITC and possible conformity actions are subject to significant uncertainty. In addition, the impacts of these different changes likely would deviate from each other over time. For example, the cost of the EITC could vary based on the economy. Additionally, revenues raised by conformity actions could change as taxpayers respond to any new incentives. This makes it difficult to craft a package of EITC and conformity changes that is revenue neutral.

Conclusion

The budget situation continues to be positive. In putting together his January budget proposal, we estimate the Governor had $20.6 billion in discretionary resources to allocate among spending and reserves. This is a larger surplus than our office projected would be available just a few months ago.

The Governor’s budget makes prudent choices in allocating these resources. Although the Governor proposes using a smaller share of resources for reserves than recent budgets, he uses almost half of the available resources to pay down some of the state’s outstanding liabilities and focuses his spending commitments on one‑time purposes.

The Governor proposes spending roughly $3 billion on an ongoing basis, which is significantly higher than other recent budget proposals. Our economic growth scenario in the November Fiscal Outlook estimated $3 billion was roughly the level of ongoing spending that the budget could support. This was just one scenario, however. Recent experience indicates revenues could be somewhat lower than either we or the administration estimated.

The Governor’s budget establishes a number of priorities for 2019‑20 and beyond, many of which align with recent legislative action. The details of many of these proposals, however, are still in development. By proposing them at the beginning of the budget process, the Governor gives the Legislature the opportunity to collaborate with the administration to shape these policies. The Legislature now can choose its own preferred mix of reserves, one‑time spending, and ongoing budget commitments.