LAO Contact

January 16, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

Overview of the Governor’s Proposition 98 Budget Package

Executive Summary

Package Generally Reasonable Starting Point but Poses Some Risk. Though we think the administration’s estimates of the K-14 funding guarantee are reasonable given the data available at the time they were prepared, subsequent economic developments (largely relating to stock prices) suggest the estimates might be revised downward somewhat in the coming months. A drop in the funding guarantee in 2018‑19 or 2019‑20 could necessitate various adjustments to the Governor’s proposed $2.9 billion K-14 spending package. Under the January budget, the Governor prioritizes new spending primarily for the Local Control Funding Formula, community college apportionments, and special education. We think these spending priorities generally are reasonable, particularly as they largely build upon recent state reform efforts. The proposed augmentations, however, are vulnerable to potential downward adjustments in May. Schools and community colleges also face additional risk relative to recent state budgets, as the Governor’s budget contains almost no one-time 2019‑20 spending, meaning ongoing K-14 programs have no corresponding protection were the guarantee to decline in 2020‑21. The Governor also proposes undoing a budget agreement enacted last year relating to Proposition 98 true-ups, with the effect of benefiting schools but making balancing the rest of the state budget even more difficult during downturns.

Introduction

The Governor presented his proposed state budget to the Legislature on January 10, 2019. In this post, we provide an overview and initial assessment of the largest piece of that budget—the Proposition 98 budget. The first section of the post focuses on major Proposition 98 spending proposals whereas the second section focuses on the administration’s estimates of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. For additional information about the Proposition 98 budget, please see our January 2019 EdBudget tables.

Proposition 98 Spending

Below, we provide an overview of the Governor’s Proposition 98 spending package and then highlight major proposals for K-12 education and the California Community Colleges (CCC). We conclude with a few high-level comments about the spending package.

Overview

Governor Proposes $2.9 Billion in New Proposition 98 Spending. This amount accounts for all new Proposition 98 spending across the 2017‑18 through 2019‑20 period. It consists of $2.8 billion for K-12 education, $367 million for the community colleges, and a net downward adjustment of $289 million to account for cost shifts (Figure 1). The largest cost shift relates to the Governor’s proposal to cover a larger share of State Preschool costs with non-Proposition 98 General Fund. Nearly all of the new Proposition 98 spending is for ongoing commitments, with only $198 million associated with one-time initiatives.

Figure 1

Governor Proposes $2.9 Billion in New Proposition 98 Spending

Reflects Ongoing Commitments Unless Otherwise Noted (In Millions)

|

K‑12 Education |

|

|

COLA and attendance adjustments for LCFF |

$2,027 |

|

Special education grants ($187 million one time) |

577 |

|

COLA for select categorical programs |

187 |

|

Full‑year cost of previously approved preschool slots |

27 |

|

COLA and attendance adjustments for COEs |

9 |

|

School district accounting system replacement project (one time) |

3 |

|

Subtotal |

($2,830) |

|

California Community Colleges |

|

|

COLA for apportionments |

$248 |

|

College Promise fee waivers for second‑year students |

40 |

|

COLA for select student support programs |

32 |

|

Enrollment growth for apportionments |

26 |

|

Student Success Completion Grants caseload adjustment |

11 |

|

Legal services for undocumented students |

10 |

|

Subtotal |

($367) |

|

Accounting Shifts |

|

|

Three K‑12 initiatives shifted to Proposition 98 budget (one time) |

$8 |

|

Preschool costs shifted to non‑Proposition 98 budget |

‑297 |

|

Subtotal |

(‑$289) |

|

Total Spending Proposalsa |

$2,908 |

|

aReflects all proposals scored to 2017‑18, 2018‑19, 2019‑20, or prior years. COLA = cost‑of‑living adjustment (3.46 percent); LCFF = Local Control Funding Formula; and COEs = county offices of education. |

|

Funding Per Student Grows Steadily, Reaches Historic High. Figure 2 shows the overall distribution of Proposition 98 funding by segment over the budget period. Under the Governor’s budget, K-12 funding per student increases from the revised 2018‑19 level of $11,574 to $12,018 in 2019‑20, an increase of $444 (3.8 percent). Community college funding per full-time equivalent (FTE) student increases from $8,099 to $8,306 in 2019‑20, an increase of $207 (2.6 percent). Adjusted for inflation, these are the highest per-student funding levels since the passage of Proposition 98 in 1988. Compared to the previous all-time high in 2000‑01, K-12 funding is up about $500 per student and community college funding is up about $600 per student. (Both historical comparisons exclude funding associated with the Adult Education Program.)

Figure 2

Proposition 98 Funding by Segment

(Dollars in Millions Except Funding Per Student)

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

Change From 2018‑19 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Segment |

|||||

|

K‑12 Educationa |

$66,778 |

$68,693 |

$71,242 |

$2,549 |

3.7% |

|

California Community Colleges |

8,720 |

9,174 |

9,438 |

264 |

2.9 |

|

Totals |

$75,498 |

$77,867 |

$80,680 |

$2,813 |

3.6% |

|

Enrollment Estimates |

|||||

|

K‑12 attendance |

5,954,720 |

5,935,229 |

5,928,175 |

‑7,054 |

‑0.1% |

|

Community college FTE students |

1,125,224 |

1,132,757 |

1,136,214 |

3,457 |

0.3 |

|

Funding Per Student |

|||||

|

K‑12 Education |

$11,214 |

$11,574 |

$12,018 |

$444 |

3.8% |

|

California Community Colleges |

7,749 |

8,099 |

8,306 |

207 |

2.6 |

|

aIncludes funding for instruction provided directly by state agencies and the portion of State Preschool funded through Proposition 98. FTE = full‑time equivalent. |

|||||

Major Proposals

Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). The largest component of the Governor’s Proposition 98 spending package is a $2 billion increase for LCFF. The increase covers a 3.46 percent statutory cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) and accounts for a projected 0.12 percent decline in student attendance. The budget also includes $187 million to provide a COLA for several K-12 programs that remain outside LCFF (most notably special education and preschool).

Special Education Grants. The Governor proposes grants totaling $577 million ($390 million ongoing and $187 million one time) to be allocated to districts based upon their unduplicated counts of low-income students, English learners, and students with disabilities. The administration indicates schools may use these funds for either (1) special education services for students with disabilities or (2) early intervention programs for students not currently receiving special education services.

Community College Apportionments. The Governor’s budget includes $248 million to cover a 3.46 percent COLA for apportionments. The budget also includes $32 million to provide a COLA for several CCC categorical programs (most notably the Adult Education Program). The budget includes $26 million to cover 0.55 percent enrollment growth (equating to about 6,000 additional FTE students).

Community College Funding Formula. The 2018‑19 budget package established a new formula for community college apportionments and phased in its implementation over several years. Under the formula, the share of apportionment funding tied to enrollment is set to decline from about 70 percent in 2018‑19 to about 60 percent in 2020‑21. Over the same period, the share tied to student outcomes is set to increase from about 10 percent to 20 percent. The Governor’s budget proposes to postpone these changes for a year, effectively keeping the enrollment and student outcome shares of apportionment funding the same in 2019‑20 as in 2018‑19. The administration indicates the proposal is intended to provide additional time for the Chancellor’s Office and the Funding Formula Oversight Committee to assess initial implementation of the formula, including the reliability and quality of the student outcome data used in determining districts’ funding allocations. The Governor also proposes to limit annual growth in a district’s student outcome allotment such that it can grow no more than 10 percent year over year.

College Promise. The 2018‑19 Budget Act included $46 million ongoing for the California College Promise program. This program waives enrollment fees for community college students without demonstrated financial need who attend their first year of college on a full-time basis. The Governor’s budget proposes an additional $40 million ongoing to cover a second year of enrollment fees for these students.

Comments

New Administration Signals Commitment to LCFF, Providing Continuity for Districts. Although LCFF was closely associated with the previous administration, the new administration indicates it is “committed to funding public schools through the LCFF.” Consistent with this intent, the Governor’s budget funds the COLA for LCFF and makes no changes to the formula, its spending requirements, or its associated system of district planning and support. Such continuity could be of significant benefit to districts as they budget, build their strategic academic plans, identify their performance problems, and access support to address those problems. The Governor’s approach also is consistent with the state’s practice over the past six years of dedicating most available Proposition 98 K-12 funding to LCFF.

Special Education Proposal Unlikely to Promote Early Intervention Programs. Because special education costs have far outpaced special education funding in recent years, most schools receiving funding under the Governor’s proposal likely would use the funds to help them cover their existing special education costs. If the Legislature wanted to promote early intervention programs, it likely would need to take a different approach—crafting a more targeted initiative with specific requirements and accountability measures. As a targeted early intervention program likely could benefit many students and keep some students from later needing more expensive special educations services, the Legislature will want to think carefully about which of the Governor’s two goals it would most like to address.

No New Major Community College Initiatives, but Greater Legislative Oversight May Be Warranted. The Governor’s budget for the community colleges builds upon several efforts started last year—funding the new apportionment formula, expanding the College Promise program, and supporting the provision of legal services to immigrant students—while not creating any new community college programs. Such continuity could simplify budgeting and planning for colleges, thereby allowing them to focus on fully implementing the numerous initiatives adopted the last few years. Such continuity might also benefit the Legislature by giving it more time to dedicate to monitoring the ongoing implementation of community college initiatives, particularly the new apportionment formula. Regarding the new formula, postponing its scheduled phase in might be warranted, but we encourage the Legislature to stay apprised of any data-quality concerns that emerge and the steps the Chancellor’s Office and the administration are taking to address these concerns.

Even Small Changes in the K-14 COLA Rate Will Have Significant Impact on the Proposition 98 Budget. Although the Governor’s estimate of the K-14 COLA rate seems reasonable at this time, even small changes to the rate have notable effects. For example, a 0.5 percentage point increase (decrease) in the rate would increase (decrease) the total cost of COLA for school and community college programs by about $370 million. Assuming no other changes in the Proposition 98 budget, a COLA cost increase of that size would mean the state could no longer fund most of the Governor’s other ongoing K-14 augmentations within projected growth of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. Conversely, a cost reduction of that size would almost double the amount of funding available for other ongoing augmentations. The federal government is scheduled to release the data the state needs to finalize the COLA rate on April 26. (The agency responsible for publishing the data, however, currently is closed due to the federal government shutdown.)

Additional Costs and Savings Likely to Materialize by May. Currently, the Governor’s budget does not reflect certain additional costs that are likely to materialize over the coming months. These costs include (1) a state payment related to a misallocation of property tax revenue for the San Francisco Unified School District in prior years, (2) grants to cover two fiscally distressed districts’ operating deficits, (3) growth in the “minimum state aid” component of the funding formula for county offices of education (COEs), (4) funding for COEs to assist districts that were identified for technical assistance after the development of the Governor’s budget, and (5) operating support for one particular joint powers agency the state has been funding on a temporary basis. The state also is likely to identify additional savings in the coming months, including recognizing additional unspent funds from prior years and lower-than-expected community college enrollment growth. The net fiscal effect of all these changes is uncertain at this time, but the changes would necessitate spending adjustments within the Proposition 98 budget.

Minimum Guarantee

Below, we (1) provide background on the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee, (2) explain how the Governor proposes to change the Proposition 98 true-up process, (3) assess the administration’s estimates of the guarantee, and (4) identify some related issues for the Legislature to consider.

Background on Minimum Guarantee

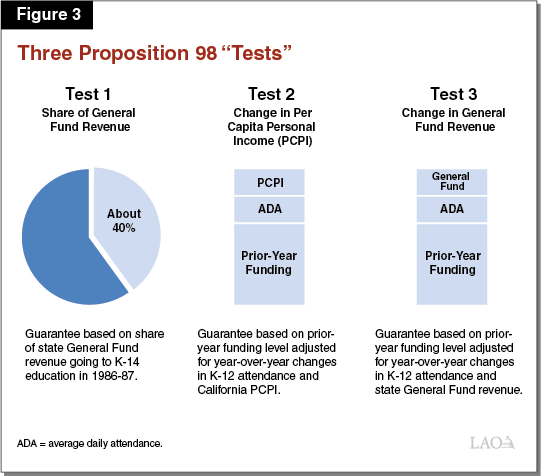

Minimum Guarantee Depends on Various Inputs and Formulas. The California Constitution sets forth three main tests for calculating the minimum guarantee. These tests depend upon several inputs, including K-12 attendance, per capita personal income, and per capita General Fund revenue (Figure 3). Depending on the values of these inputs, one of the three tests becomes “operative” and determines the minimum guarantee for that year. Historically, Test 2 and Test 3 have been operative more frequently than Test 1. When Test 2 or Test 3 is operative, the minimum guarantee equals the amount of funding provided the previous year adjusted for changes in student attendance and a growth factor tied to per capita personal income (Test 2) or per capita General Fund revenue (Test 3). The state meets the guarantee through a combination of General Fund and local property tax revenue, with increases in property tax revenue usually reducing General Fund costs dollar for dollar. Though the state can fund schools and community colleges at a level higher than required by the formulas, the state typically funds at or near the guarantee. With a two-thirds vote of each house of the Legislature, the state can suspend the guarantee and provide less funding than the formulas require that year.

Student Attendance Adjustment Includes Two-Year “Hold Harmless” Provision. Although the state generally adjusts the minimum guarantee for changes in student attendance whenever Test 2 or Test 3 applies, the State Constitution provides an exception when attendance begins to decline. Specifically, the Constitution specifies that the minimum guarantee is not adjusted downward for declines in attendance unless attendance has also declined the two previous years. (This constitutional provision is separate from the statutory provision allowing individual school districts to have their LCFF allotments based on the higher of their current- or prior-year attendance.)

“Maintenance Factor” Payments Required in Certain Years. In addition to the three main Proposition 98 tests, the Constitution requires the state to track an obligation known as maintenance factor. The state creates a maintenance factor obligation when Test 3 is operative (that is, General Fund revenue is growing relatively slowly) or when it suspends the guarantee. The obligation equals the difference between the actual level of funding provided and the Test 1 or Test 2 level (whichever is higher). Each year moving forward, the state adjusts any outstanding maintenance factor for changes in K-12 attendance and per capita personal income. The Constitution requires the state to make maintenance factor payments when General Fund revenue grows relatively quickly. The magnitude of these payments is determined by formula, with stronger revenue growth generally requiring larger payments. These maintenance factor payments become part of the base for calculating the minimum guarantee the following year.

Proposition 98 True-Ups

State Typically Trues Up K-14 Funding When the Minimum Guarantee Changes. Historically, the state continues to revise its estimate of the minimum guarantee for at least nine months after the close of the fiscal year. Given that the relevant inputs can change from the budget act through the end of this period, the final calculation of the guarantee almost always differs from the initial estimate. When the final guarantee is higher than the initial estimate, the state makes a one-time payment to “settle up” to the higher guarantee. Sometimes the state makes the settle-up payment immediately. In other cases, the state records a settle-up obligation but does not make the associated payment for several years. When the final guarantee is lower than the initial estimate, the state often adjusts K-14 funding down to the lower guarantee. If an outstanding settle-up obligation exists, the state typically scores the difference as a settle-up payment, thereby not reducing school funding for that year but recognizing a lower base for calculating the guarantee moving forward. If no outstanding settle-up obligation exists or the state’s budget condition is poor, the state typically reduces funding through program cuts and payment deferrals (which also creates a lower base moving forward). The state historically makes all these types of adjustments through the regular budget process.

2018‑19 Budget Plan Established an Automatic True-Up Process. Chapter 39 of 2018 (AB 1825, Committee on the Budget) created a Proposition 98 true-up account to automatically adjust school funding when estimates of the guarantee change. For years in which the guarantee drops, the state is to credit the funding above the guarantee to the true-up account. For those years in which the guarantee increases, the state is to apply any credits in the true-up account toward meeting the higher guarantee. If the credits are insufficient to meet the higher guarantee, the state is to make a settle-up payment for the remaining difference. The basic purpose of the true-up account is to make unexpected changes in the guarantee and associated funding adjustments somewhat less disruptive for schools, community colleges, and the state.

Governor Proposes to Eliminate Automatic True-Up Process. The Governor proposes to repeal the true-up account. The Governor also proposes to prohibit the state from making any downward adjustment to school funding once a fiscal year is over, while still requiring the state to make upward adjustments.

Governor’s Estimates of the Minimum Guarantee

2017‑18 Minimum Guarantee Revised Down $164 Million. Compared with the estimates made in June 2018, the 2017‑18 minimum guarantee has dropped $164 million (Figure 4). About half of this drop is related to lower student attendance. Whereas the June budget plan assumed attendance would increase slightly, the latest available data indicate a slight decline. The state’s 2017‑18 maintenance factor obligation also is revised downward by $124 million to reflect various adjustments to the minimum guarantee for years prior to 2017‑18. The drops associated with attendance and the maintenance factor payment are partially offset by higher General Fund revenue. After updating estimates of LCFF and revising costs downward (largely due to lower-than-expected attendance), the Governor’s budget leaves Proposition 98 funding $44 million above the minimum guarantee.

Figure 4

Tracking Changes in Proposition 98 Funding

(In Millions)

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

||||||

|

June 2018 Estimate |

January 2019 Estimate |

Change |

June 2018 Estimate |

January 2019 Estimate |

Change |

||

|

Minimum Guarantee |

|||||||

|

General Fund |

$53,381 |

$52,843 |

‑$538 |

$54,870 |

$54,028 |

‑$842 |

|

|

Local property tax |

22,236 |

22,610 |

374 |

23,523 |

23,839 |

316 |

|

|

Total Guarantee |

$75,618 |

$75,453 |

‑$164 |

$78,393 |

$77,867 |

‑$526 |

|

|

General Fund above guarantee |

$0 |

$44 |

$44 |

$0 |

$0 |

— |

|

|

Settle‑up payment for LCFF |

0 |

0 |

— |

0 |

475 |

475 |

|

|

Total Funding |

$75,618 |

$75,498 |

‑$120 |

$78,393 |

$78,342 |

‑$50 |

|

|

Operative “Test” |

2 |

1 |

— |

2 |

3 |

— |

|

|

LCFF = Local Control Funding Formula. |

|||||||

2018‑19 Minimum Guarantee Revised Down $526 Million. Compared with the estimates made in June 2018, the 2018‑19 minimum guarantee has dropped $526 million. This drop is mainly due to the attendance-related hold harmless provision not being applicable in 2018‑19 and the downward revision to attendance estimates in 2017‑18 carrying forward. Another factor contributing to the drop is slightly slower year-to-year growth in General Fund revenue. The result of these changes, in combination with various smaller adjustments, is that school and community college funding is $475 million higher than the revised estimate of the guarantee. The Governor proposes to reclassify this funding as a settle-up payment (discussed more in the next section). This action results in $475 million related to LCFF costs being taken “off books” in 2018‑19 and counted instead toward prior years (mainly 2009‑10).

2019‑20 Minimum Guarantee Up $2.8 Billion Over Revised 2018‑19 Level. The administration estimates that the 2019‑20 minimum guarantee is $80.7 billion, an increase of $2.8 billion (3.6 percent) over the revised 2018‑19 level (Figure 5). Test 1 is operative, with the guarantee receiving a fixed share (about 40 percent) of state General Fund revenue. Although the minimum guarantee is not growing as quickly as per capita personal income, the state creates no new maintenance factor (consistent with its recent practice in these situations). Regarding spending, the Governor’s budget dedicates virtually all of the new funding attributable to the 2019‑20 guarantee for ongoing purposes. Of the $2.8 billion total increase in 2019‑20, only $3 million is dedicated to one-time initiatives. (All other one-time funding is associated with earlier fiscal years.)

Figure 5

Proposition 98 Key Inputs and Outcomes Under Governor’s Budget

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

|

|

Proposition 98 Funding |

|||

|

General Fund |

$52,887a |

$54,028 |

$55,295 |

|

Local property tax |

22,610 |

23,839 |

25,384 |

|

Totals |

$75,498 |

$77,867 |

$80,680 |

|

Change From Prior Year |

|||

|

General Fund |

$2,648 |

$1,141 |

$1,268 |

|

Percent change |

5.3% |

2.2% |

2.3% |

|

Local property tax |

$1,207 |

$1,229 |

$1,545 |

|

Percent change |

5.6% |

5.4% |

6.5% |

|

Total funding |

$3,855 |

$2,370 |

$2,813 |

|

Percent change |

5.4% |

3.1% |

3.6% |

|

Operative Test |

1 |

3 |

1 |

|

Maintenance Factor |

|||

|

Amount created (+) or paid (‑) |

‑$1,201 |

$143 |

— |

|

Total outstandingb |

— |

143 |

$150 |

|

Growth Rates |

|||

|

K‑12 average daily attendance |

‑0.13% |

‑0.33% |

‑0.12% |

|

Per capita personal income (Test 2) |

3.69 |

3.67 |

5.07 |

|

Per capita General Fund (Test 3)c |

10.20 |

3.48 |

3.33 |

|

K‑14 cost‑of‑living adjustment |

1.56 |

2.71 |

3.46 |

|

aIncludes $44 million provided on top of the minimum guarantee. bOutstanding maintenance factor is adjusted annually for changes in K‑12 attendance and per capita personal income. cAs set forth in the State Constitution, reflects change in per capita General Fund plus 0.5 percent. |

|||

2019‑20 Guarantee Calculation Includes Adjustment for Shift of Preschool Funding. The Governor’s budget proposes to shift funding for part-day State Preschool programs operated by nonprofit agencies from the Proposition 98 to non-Proposition 98 side of the budget. As a result of the shift, all funding for nonprofit agencies running State Preschool programs—either part-day or full-day programs—would be funded from the non-Proposition 98 side of the budget. (Preschool programs operated by local educational agencies would remain funded within Proposition 98.) In tandem with this shift, the Governor proposes to “rebench” the minimum guarantee down by $297 million in 2019‑20 (reflecting the approximate cost of the programs being shifted after adjusting for growth and COLA).

Property Tax Revenue Revised Upward Over the Period. For 2017‑18 and 2018‑19, the administration revises its estimate of property tax revenue upward by $374 million and $316 million, respectively, largely to reflect updated data reported by schools and community colleges. For 2019‑20, the administration estimates that property tax revenue will grow $1.5 billion (6.5 percent) over the revised 2018‑19 level (Figure 5). This increase mainly reflects the administration’s estimate that assessed property values will grow 6.8 percent in 2019‑20, with somewhat slower growth in various smaller property tax components.

Additional Proposition 98-Related Funding

Budget Includes Settle-Up Payment. The Governor’s budget provides $687 million as a settle-up payment related to meeting the minimum guarantee in various years prior to 2017-18. Figure 6 shows the years for which the state owes settle-up and how the proposed settle-up payment would be used. The largest component of the payment is the $475 million to cover LCFF costs that otherwise would exceed the minimum guarantee in 2018-19. The budget dedicates the rest of the payment to covering a large portion of the proposed one-time special education grants and a small portion of ongoing Community College Strong Workforce Program costs. After making the $687 million settle-up payment, the state would have paid off all Proposition 98 settle-up obligations. In contrast to previous years, the settle-up payment would not be scored as a Proposition 2 debt payment. (Technically, $654 million of the proposed settle-up payment could be scored as a Proposition 2 debt payment.)

Figure 6

Outstanding Settle‑up Obligation and

Governor’s Payment Proposal

(In Millions)

|

Outstanding Settle‑Up by Year |

|

|

2009‑10 |

$435 |

|

2011‑12 |

48 |

|

2013‑14 |

172 |

|

2014‑15 |

32 |

|

2016‑17 |

1 |

|

Total |

$687 |

|

Settle‑Up Payment Proposal |

|

|

Ongoing 2018‑19 LCFF costs |

$475 |

|

One‑time special education grants |

178 |

|

Ongoing 2019‑20 CCC Strong Workforce Program costs |

34 |

|

Total |

$687 |

|

LCFF = Local Control Funding Formula and CCC = California Community Colleges. |

|

Comments

Administration’s Initial Estimates of the Guarantee Are in Line With Our November Estimates. We reviewed the administration’s estimates of the various Proposition 98 inputs as well as its calculations of the minimum guarantee. We think the administration’s estimates of the guarantee offer a reasonable starting point for budget deliberations. Compared to our November outlook, the administration’s estimates of the guarantee are less than $100 million higher than ours across the three-year period.

Recent Drop in Stock Prices Is Not Reflected in Governor’s January Estimates. Though the administration’s initial estimates of the guarantee appear reasonable based upon the data that was available at the time the Governor’s budget was prepared, the initial estimates do not account for recent economic developments. Notably, stock prices fell sharply at the end of 2018 and currently sit more than 10 percent below their September peak. Unless stock prices increase significantly in the coming months, capital gains revenue estimates in May likely will be lower than the January assumptions. As discussed more in the next paragraph, lowered revenue estimates correspondingly would lower estimates of the minimum guarantee.

Minimum Guarantee Is Moderately Sensitive to Revenue Changes in 2018-19 and 2019-20. To help the Legislature plan for possible budget changes in the coming months, we examined how lower or higher state revenue would affect the minimum guarantee. For 2018-19, the guarantee drops about 55 cents for each dollar of lower revenue. The guarantee increases about 55 cents for each dollar of the first $250 million in higher revenue. Revenue increases beyond $250 million would not increase the guarantee, as Test 2 would become the operative test. For 2019-20, the dynamics are more straightforward. For a dollar increase or decrease in revenue, the minimum guarantee correspondingly would increase or decrease by about 40 cents. The guarantee in 2019-20 also is not likely to depend upon the prior-year level of Proposition 98 funding, as Test 1 is likely to be operative. This means a one-time revenue drop in 2018-19 would not have an interactive effect on the 2019-20 guarantee. (For this revenue sensitivity analysis, we hold all Proposition 98 inputs other than revenue constant. Although the other inputs tend to be less volatile than General Fund revenue, they too are likely to change over the coming months.)

Proposition 98 Budget Currently Contains No Cushion Against Potential Downturn. Over the past six years, the state has set aside an average of about $700 million per year inside the guarantee for one-time purposes. The exact amount has ranged from a high of $1.2 billion to a low of $413 million. (These amounts exclude one-time funds associated with prior-year true-ups and settle-up payments.) The main advantage of dedicating some funding inside the guarantee for one-time purposes is that it provides a measure of protection against future volatility in the guarantee. If the guarantee experiences a year-over-year decline, the expiration of one-time initiatives provides a buffer that reduces the likelihood of cuts to ongoing programs. The Governor’s proposed budget, however, dedicates just $3 million inside the 2019-20 guarantee for one-time purposes. Moreover, the Governor’s budget uses $77 million in one-time funds to pay for a portion of the ongoing CCC Strong Workforce Program. Using one-time funds for ongoing costs builds a shortfall into the Proposition 98 budget the following year, effectively reducing the augmentations schools could expect in 2020-21. These features of the Governor’s budget could leave schools and the state in a difficult position if the guarantee were to decline in 2020-21.

State Has Not Built Up a Reserve Dedicated to Schools and Community Colleges. Another factor that could make school funding more vulnerable to an economic downturn is that the state has made no deposit to date in the Public School System Stabilization Account. This account was created by Proposition 2 (2014) in tandem with the Budget Stabilization Account. Deposits into either account are predicated on relatively high revenue from capital gains, though the rules for the school account are notably more restrictive. Over the past several years, the state effectively has been saving rather than spending high capital gains revenue on behalf of the rest of the budget. By contrast, the state has been giving schools their share of the high capital gains revenue. (While the state has nothing in the statewide school reserve, data show that schools themselves are increasing their local reserves to some extent. Whereas local unrestricted reserves averaged 15 percent in 2013-14, they averaged 18 percent in 2016-17, the latest year available.)

Changes to True-Up Process Increase Risk to State Budget. The state historically has adjusted school funding both upward and downward in response to changes in the minimum guarantee occurring after enactment of the budget. The Proposition 98 true-up account automated these adjustments but kept the same basic approach of making both upward and downward adjustments. By contrast, the Governor’s proposal would have the rest of the state budget assume the risk of any changes to the minimum guarantee occurring after the end of the year. The state would continue to be required to make settle-up payments if the guarantee increased, but it would be prohibited from taking any action to align school funding with a lower guarantee. Not aligning school funding with the guarantee in one year also has future implications, as the guarantee the next year is typically higher than it would be otherwise. Though such an approach clearly offers a benefit for schools, it can make balancing the rest of the state budget during an economic downturn all the more difficult.

Conclusion

This post is based upon our initial review of the basic architecture of the Governor’s Proposition 98 budget package. We have already begun reviewing certain elements of this package more closely. In the coming weeks, we plan to release additional budget reports containing these more in-depth analyses.