LAO Contacts

- Anita Lee

- Judicial Branch

- Department of Justice

- Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training

- Caitlin O'Neil

- Prisons, Board of Parole Hearings

- Board of State and Community Corrections

- Luke Koushmaro

- Rehabilitation

- Juvenile Justice

- Drew Soderborg

- Overall Criminal Justice

February 19, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

Analysis of the Governor's

Criminal Justice Proposals

- Criminal Justice Budget Overview

- Cross‑Cutting Issue: Deferred Maintenance

- California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

- Judicial Branch

- Department of Justice

- Local Public Safety

- Summary of Recommendations

Executive Summary

In this report, we assess many of the Governor’s budget proposals in the judicial and criminal justice area and recommend various changes. Below, we summarize some of our major recommendations. We provide a complete listing of our recommendations at the end of the report.

Budget Provides $18 Billion for Criminal Justice Programs

The Governor’s 2019‑20 budget includes a total of $18.2 billion from all fund sources for the operation of judicial and criminal justice programs. This is a net increase of $271 million (1.5 percent) over the revised 2018‑19 level of spending. General Fund spending is proposed to be $14.9 billion in 2019‑20, which represents an increase of $183 million (1 percent) above the revised 2018‑19 level.

Budget Includes Numerous Proposals Lacking Key Details

Pretrial Release Grant Program. The Governor’s budget proposes $75 million from the General Fund on a one‑time basis for Judicial Council to administer a two‑year grant program related to pretrial release. While the proposed program could be worthwhile, the Legislature currently lacks sufficient information to effectively evaluate the proposal and weigh the proposed funding relative to its other General Fund priorities. We recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to provide a well‑developed proposal that specifies (1) the primary goals of the program, (2) the specific programs or activities that would be funded, (3) how funding would be allocated, and (4) how funded programs or activities would be evaluated to inform statewide decision‑making.

Deferred Maintenance. The budget proposes $65 million from the General Fund to implement deferred maintenance projects at the judicial branch and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). Unlike the judicial branch, at the time of this analysis CDCR had not provided our office with a list of the specific projects it would prioritize with the proposed funding. Prior to approving the proposed funding for CDCR, we recommend the Legislature require the department to report on what projects it intends to implement to ensure that it will focus on high‑priority maintenance activities. We also recommend adoption of reporting requirements to increase oversight of (1) how CDCR and the judicial branch maintain their facilities on an ongoing basis and (2) what deferred maintenance projects are actually implemented with the proposed funding.

Structured Decision‑Making Framework for Parole Hearings. The administration proposes $4.9 million from the General Fund and the implementation of a structured decision‑making framework for the Board of Parole Hearings (BPH) to accommodate an increase in parole hearings. While we find the proposed use of a decision‑making framework to be promising, BPH has not provided a prototype of the framework or important details on its process for developing, implementing, and evaluating the framework. We recommend that the Legislature require BPH to provide such information, so that it can effectively evaluate this potentially significant policy change.

Compensation for Attorneys Appointed by BPH. The Governor’s budget includes $2.5 million from the General Fund to increase pay for attorneys who represent inmates in parole hearings. While a new attorney pay structure appears needed, the Legislature currently lacks sufficient information to effectively evaluate the proposal. As such, we recommend that the Legislature require BPH to provide key information this spring about its proposed changes to the attorney pay schedule, including the basis for the proposed pay increase and the new structure of the proposed pay schedule.

New Tattoo Removal Program. The Governor’s budget proposes $2.5 million from the General Fund for CDCR to establish a tattoo removal program that would be available at all state prisons. We find that the proposed program could result in certain benefits, such as better employment prospects for inmates that receive the service. However, the Governor’s proposal lacks key pieces of information that makes it very difficult for the Legislature to assess whether the proposed program would be effective and whether the requested funding is appropriate. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature direct the department to provide additional information on the proposed program, including how many inmates would be served by the program and how it would be structured and evaluated.

Budget Includes Several Proposals Related to Special Fund Shortfalls

Increased Resources for Peace Officer Training. The Governor’s budget proposes a $34.9 million ongoing General Fund augmentation for the Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST) to restore and expand programs and services that were cut due to past shortfalls in the criminal fine and fee revenue supporting the program. We recommend the Legislature ensure that any funding provided and the planned expenditure of such funding reflect its priorities. To the extent that the Legislature approves additional funding for POST, we also recommend adopting trailer bill language directing POST to report annually on specific outcome and performance measures that are tied to legislative expectations for the additional funding.

Bureau of Firearms (BOF) Workload. The Governor’s budget proposes a series of adjustments related to BOF that are intended to prevent the Dealer’s Record of Sale (DROS) Special Account—which is supported by fee revenues—from becoming insolvent and to accommodate additional BOF workload. While the overall proposal is a step in the right direction, it does not fully address the identified problems, and results in some unintended consequences. As such, we recommend an alternative package of adjustments that allocates the funding in a different manner, but addresses the concerns with the Governor’s proposal. We also recommend that the Legislature require a report from the Department of Justice and the administration on addressing the ongoing operational shortfalls facing the DROS Special Account and another special fund that supports BOF—the Firearms Safety and Enforcement Special Fund.

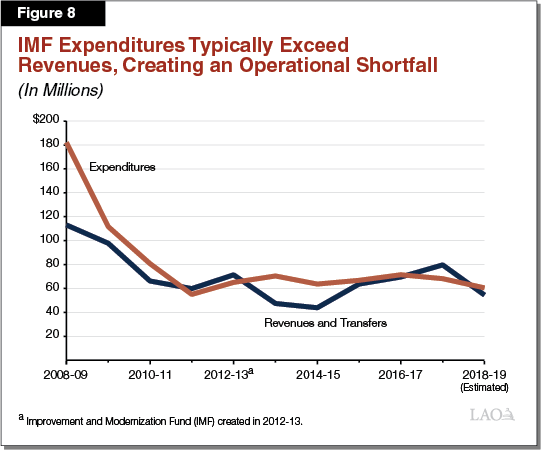

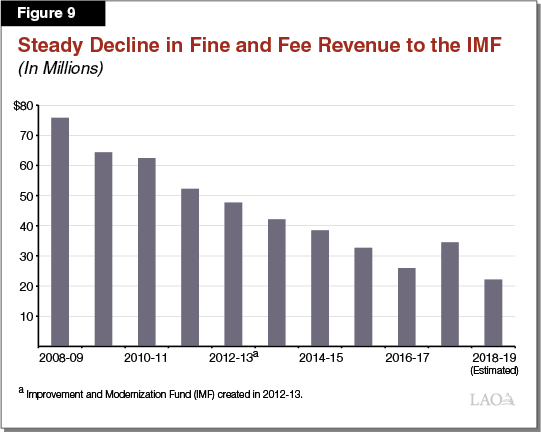

Improvement and Modernization Fund (IMF). The budget proposes General Fund resources for the trial court Phoenix financial procurement, and payroll system and the judicial branch’s Litigation Management Program, in order to offset existing IMF support for these programs and support increased costs. While the Governor’s proposal would help prevent the IMF from becoming insolvent in 2019‑20, it is projected to face operational shortfalls and potential insolvency in the future—largely due to a steady decline in criminal fine and fee revenue deposited into the fund. In order to address these concerns, we recommend the Legislature (1) deposit IMF revenues into the General Fund and eliminate the IMF and (2) direct the judicial branch to report on each program currently receiving IMF funding (such as past expenditures and benefits achieved) to help determine what level of funding is appropriate to provide these programs. Given that it will take time to complete this report and for the Legislature to consider the information as part of its budget priorities, we recommend providing one‑time General Fund support for these programs.

Criminal Justice Budget Overview

The primary goal of California’s criminal justice system is to provide public safety by deterring and preventing crime, punishing individuals who commit crime, and reintegrating offenders back into the community. The state’s major criminal justice programs include the court system, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), and the California Department of Justice (DOJ). The Governor’s budget for 2019‑20 proposes total expenditures of $18.2 billion for the operations of judicial and criminal justice programs. Below, we describe recent trends in state spending on criminal justice and provide an overview of the major changes in the Governor’s proposed budget for criminal justice programs in 2019‑20.

State Operational Expenditure Trends

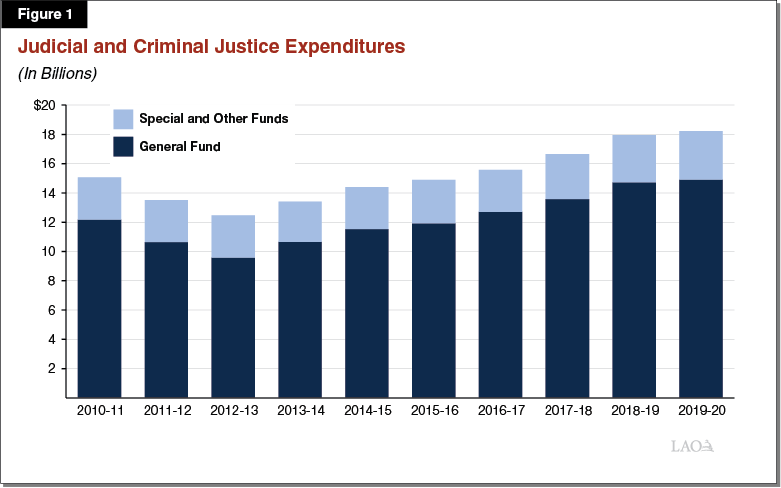

Total Spending Declined Between 2010‑11 and 2012‑13 . . . As shown in Figure 1, total state expenditures on the operation of criminal justice programs declined between 2010‑11 and 2012‑13, primarily due to two factors. First, in 2011 the state realigned various criminal justice responsibilities to the counties, including the responsibility for certain low‑level felony offenders. This realignment reduced state correctional spending. Second, the judicial branch—particularly the trial courts—received significant one‑time and ongoing General Fund reductions.

. . . But Has Increased Since Then. However, overall spending for the operational support of criminal justice programs has increased steadily since 2012‑13. This was largely due to additional funding for CDCR and the trial courts. For example, increased CDCR expenditures resulted from (1) increases in employee compensation costs, (2) the activation of a new health care facility, and (3) costs associated with the department taking responsibility for inpatient psychiatric programs from the Department of State Hospitals. During this same time period, various augmentations were provided to the trial courts to offset reductions made in prior years and to fund specific activities.

Governor’s Budget Proposals

Total Proposed Spending of $18.2 Billion in 2019‑20. As shown in Figure 2, the Governor’s 2019‑20 budget includes a total of $18.2 billion from all fund sources for the operation of judicial and criminal justice programs (excluding planned capital outlay expenditures). This is a net increase of $271 million (1.5 percent) over the revised 2018‑19 level of spending. General Fund spending is proposed to be $14.9 billion in 2019‑20, which represents an increase of $183 million (1 percent) above the revised 2018‑19 level. We note that this increase does not include increases in 2019‑20 employee compensation costs for these departments, which are budgeted elsewhere. If these costs were included, the increase would be somewhat higher.

Figure 2

Judicial and Criminal Justice Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Actual |

Estimated |

Proposed |

Change From |

||

|

Actual |

Percent |

||||

|

Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation |

$11,813 |

$12,555 |

$12,582 |

$28 |

0.2% |

|

General Funda |

11,487 |

12,239 |

12,279 |

40 |

0.3 |

|

Special and other funds |

326 |

315 |

303 |

‑12 |

‑3.9 |

|

Judicial Branchb |

$3,669 |

$3,862 |

$4,172 |

$310 |

8.0% |

|

General Fund |

1,735 |

1,911 |

2,129 |

217 |

11.4 |

|

Special and other funds |

1,934 |

1,951 |

2,043 |

92 |

4.7 |

|

Department of Justice |

$841 |

$996 |

$1,034 |

$39 |

3.9% |

|

General Fund |

235 |

294 |

331 |

37 |

12.6 |

|

Special and other funds |

606 |

702 |

703 |

2 |

0.2 |

|

Board of State and Community Corrections |

$93 |

$271 |

$164 |

‑$107 |

‑39.5% |

|

General Fund |

64 |

182 |

66 |

‑115 |

‑63.5 |

|

Special and other funds |

29 |

90 |

98 |

8 |

9.3 |

|

Other Departmentsc |

$235 |

$269 |

$272 |

$2 |

0.9% |

|

General Fund |

68 |

99 |

103 |

4 |

4.3 |

|

Special and other funds |

167 |

170 |

168 |

‑2 |

‑1.1 |

|

Totals, All Departments |

$16,650 |

$17,953 |

$18,224 |

$271 |

1.5% |

|

General Fund |

13,588 |

14,725 |

14,908 |

183 |

1.2 |

|

Special and other funds |

3,062 |

3,228 |

3,316 |

88 |

2.7 |

|

aDoes not include revenues to General Fund to offset corrections spending from the federal State Criminal Alien Assistance Program. bIncludes funds received from local property tax revenue. cIncludes Office of the Inspector General, Commission on Judicial Performance, Victim Compensation Board, Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training, State Public Defender, funds provided for trial court security, and debt service on general obligation bonds. Note: Detail may not total due to rounding. |

|||||

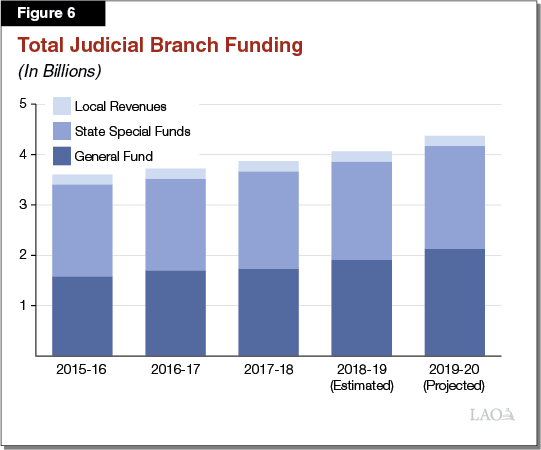

Major Spending Proposals. The most significant piece of new spending included in the Governor’s budget relates to various proposals to increase General Fund support for the judicial branch by a total of $217 million, including $75 million for grants related to pretrial release decision‑making, $60 million for the maintenance of trial court facilities, and $44 million for the replacement of case management systems and various other information technology (IT) projects. We note that the proposed spending increases are partially offset by decreases in funding, primarily due to the expiration of one‑time grant funding provided to the Board of State and Community Corrections (BSCC) in 2018‑19.

Cross‑Cutting Issue: Deferred Maintenance

The administration proposes $65 million from the General Fund to implement deferred maintenance projects at the judicial branch and CDCR. Prior to approving the proposed funding for CDCR, we recommend the Legislature require the department to report on what projects it intends to implement to ensure that it will focus on high‑priority maintenance activities. We further recommend adoption of reporting requirements that will better enable legislative oversight of (1) how CDCR and the judicial branch maintain their facilities on an ongoing basis and (2) what deferred maintenance projects are actually implemented with the proposed funding.

Background

Recent Budgets Have Provided Funding for Deferred Maintenance Projects. Facilities require routine maintenance, repairs, and replacement of parts to keep them in acceptable condition and to preserve and extend their useful lives. When such maintenance is delayed or does not occur, we refer to this as deferred maintenance. Since 2015‑16, annual state budgets have included a combined total of $1.3 billion—mostly from the General Fund—to address backlogs of deferred maintenance at state facilities—such as prisons, parks, and universities—as well as a few local facilities, such as community colleges. Of this total, $95 million has been allocated to the judicial branch and $79 million to CDCR. (In addition, CDCR received $35 million in 2017‑18 and $72 million in 2018‑19 to replace roofs and fix water damage at several facilities.)

Governor’s Proposal

Budget Provides $65 Million for Deferred Maintenance for Judicial Branch and CDCR. The Governor’s budget proposes $65 million from the General Fund in 2019‑20 for deferred maintenance projects at the judicial branch ($40 million) and CDCR ($25 million). (Additionally, the budget includes $7 million in 2019‑20 and $124 million in 2020‑21 for some specific roof and fire alarm replacement projects at CDCR.) The budget also includes provisional language allowing up to three years—until June 30, 2022—for departments to expend or encumber these funds.

Funding Represents Relatively Small Share of Identified Deferred Maintenance Projects. The judicial branch and CDCR report $2.4 billion and $1 billion, respectively, in total deferred maintenance needs. Identified projects include replacements of major building systems (such as heating, ventilation, and air condition systems), replacements of locking mechanisms on cell doors, and elevator repairs. The Governor’s proposed funding for deferred maintenance in 2019‑20 would allow the judicial branch to address roughly 1 percent of its deferred maintenance backlog and CDCR to address roughly 3 percent of its backlog.

LAO Assessment

Properly Maintaining State Facilities Is Important Practice. The proposed deferred maintenance funding reflects the continuation of an important commitment by the state to tackle its deferred maintenance backlog. The state has invested many billions of dollars to build its infrastructure assets, which play critical roles in the state’s economy and the provision of services to Californians. Moreover, when repairs to key building and infrastructure components are put off, facilities can eventually require more expensive investments, such as emergency repairs (when systems break down), capital improvements (such as major rehabilitation), or replacement. Thus, while deferring regular maintenance lowers costs in the short run, it often results in substantial costs in the long run. For example, failure to implement a relatively inexpensive maintenance project to patch a leaking roof can result in structural damage, mold, and roof replacement projects costing hundreds of thousands of dollars or more.

Judicial Branch Has Identified How It would Prioritize Funding, but Not CDCR. The judicial branch has provided information specifying which projects it would prioritize for the limited funding provided. Specifically, the judicial branch intends to prioritize projects based on cost and risk to building occupants, such as repairs to building systems that represent the greatest risk to building occupants. In line with this approach, the judicial branch plans on using the proposed funding to address the highest priority fire alarm systems. The specific projects identified in their request were selected based on the level of risk for occupants, input from building operations staff, and/or issues identified by the Office of the State Fire Marshal.

At the time of this analysis, however, CDCR had not provided our office with a list of the specific deferred maintenance projects it plans to fund with the proposed $25 million. The absence of a prioritized list of projects makes it impossible for the Legislature to determine whether the proposed funding would go to the projects that it thinks most important. For example, the Legislature may wish to prioritize funding certain types of projects—such as those that address fire, life, and safety issues or reduce future state costs—over other types of projects—such as those that would address aesthetic concerns or occur at facilities the Legislature may no longer consider necessary.

LAO Recommendations

Ensure CDCR Prioritizes Most Important Projects. We recommend that the Legislature use its budget hearings this spring to gather more information from CDCR. First, we recommend that the Legislature require CDCR to report at budget hearings on the approach it is taking to prioritize projects. This would enable the Legislature to ensure that it is comfortable that the department’s approach would result in the selection of projects that are consistent with legislative priorities.

Second, we recommend that the Legislature require CDCR to provide a specific list of projects that it plans to undertake with the requested $25 million in 2019‑20. This list is important for the Legislature to have in order to assess whether the specific proposed projects are consistent with its priorities—such as projects that prevent future costs or address fire, life, or safety risks. If the list includes projects that it deems to be of lower priority, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to reprioritize projects or adjust the funding level accordingly. If CDCR fails to provide a list of proposed projects or is unable to justify its proposed projects to the Legislature’s satisfaction, we recommend that the Legislature reject the administration’s proposed $25 million augmentation for CDCR. We note that it should generally not be difficult for CDCR to provide a list of proposed projects since the Department of Finance (DOF) issued a budget letter in July 2018 directing departments to provide prioritized lists of projects by September 2018 in preparation for the 2019‑20 budget process. (DOF also provided departments with similar direction in previous years.)

Monitor Accumulation of Deferred Maintenance. We recommend that the Legislature adopt Supplemental Report Language (SRL) requiring that, no later than January 1, 2023, CDCR and the judicial branch identify how their deferred maintenance backlog has changed since 2019. We further recommend that the SRL require that, to the extent a department’s backlog has grown in the intervening years, the department shall identify (1) the reasons for the increase and (2) specific steps it plans to take to improve its maintenance practices on an ongoing basis. This is because, if a department experienced a large increase in its backlog, it might suggest that its actual routine maintenance activities are insufficient to keep up with its annual needs and that it should improve its maintenance program to prevent the further accumulation of deferred maintenance. In such cases, it will be important for the Legislature to understand this so it can direct departments to take actions to improve their maintenance programs. Adoption of the following language would be consistent with this recommendation:

Item xxxx‑xxx‑xxxx. No later than January 1, 2023, [insert department name] shall submit to the fiscal committees of the Legislature and the Legislative Analyst’s Office a report identifying the total size of its deferred maintenance backlog as of the 2018‑19 fiscal year and September 2022. To the extent that the total size of the deferred maintenance backlog has increased over that period, the department’s report shall also identify the reasons for the increase in the size of the backlog and the specific steps the department plans to take to improve its maintenance practices on an ongoing basis.

Require Future Reporting of Projects Completed. In our budget report, The 2019‑20 Budget: Deferred Maintenance, we recommend that the Legislature adopt additional SRL requiring DOF to report, no later than January 1, 2023, on which deferred maintenance projects all departments undertook with 2019‑20 funds. This would provide greater transparency and accountability of the funds by ensuring that the Legislature has information on what projects were ultimately implemented and that the funds were spent consistent with any legislative directive given.

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

Overview

CDCR is responsible for the incarceration of adult felons, including the provision of training, education, and health care services. As of January 16, 2019, CDCR housed about 127,000 adult inmates in the state’s prison system. Most of these inmates are housed in the state’s 35 prisons and 42 conservation camps. About 5,700 inmates are housed in either in‑state or out‑of‑state contracted prisons. The department also supervises and treats about 48,800 adult parolees and is responsible for the apprehension of those parolees who commit parole violations. In addition, 675 juvenile offenders are housed in facilities operated by CDCR’s Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ), which includes three facilities and one conservation camp.

Operational Spending Proposed for 2019‑20. The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $12.6 billion ($12.3 billion General Fund) for CDCR operations in 2019‑20. Figure 3 shows the total operating expenditures estimated in the Governor’s budget for the past and current years and proposed for the budget year. As the figure indicates, the proposed spending level is an increase of $28 million, or less than 1 percent, from the estimated 2018‑19 spending level. This increase reflects additional funding to (1) address deferred maintenance backlogs, (2) replace vehicles, and (3) support the ongoing preventative maintenance of CDCR facilities. This additional proposed spending is partially offset by various spending reductions, including reduced spending for contract beds. (The proposed $28 million increase does not include anticipated increases in employee compensation costs in 2019‑20 because they are accounted for elsewhere in the budget. These increases are currently budgeted to exceed a couple hundred million dollars.)

Figure 3

Total Expenditures for the California Department of

Corrections and Rehabilitation

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

Change From |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Adult Institutions |

$10,434 |

$11,029 |

$11,022 |

‑$7 |

— |

|

Adult Parole |

637 |

706 |

729 |

23 |

3% |

|

Administration |

500 |

560 |

553 |

‑8 |

‑1 |

|

Juvenile Institutions |

193 |

208 |

217 |

9 |

4 |

|

Board of Parole Hearings |

48 |

51 |

61 |

10 |

19 |

|

Totals |

$11,813 |

$12,555 |

$12,582 |

$28 |

0.2% |

Capital Outlay Spending Proposed for 2019‑20. The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $148 million ($93 million General Fund) for CDCR capital outlay projects in 2019‑20. This amount includes (1) $77 million in additional General Fund support to continue previously approved projects and to begin one new project at existing CDCR facilities, (2) $55 million in General Fund lease revenue bonds for various counties to construct or renovate juvenile correctional facilities through a program first authorized by Chapter 175 of 2007 (SB 81, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review), and (3) $16 million previously appropriated from the General Fund to support previously approved projects.

Trends in the Adult Inmate and Parolee Populations

We recommend that the Legislature require the administration to account for recent policy changes in its spring inmate and parolee population projections and budget requests at the May Revision. Until such information is provided, we withhold recommendation on the administration’s adult population funding request. In addition, we recommend requiring CDCR to report to the Legislature when it makes future changes to credit policies.

Background

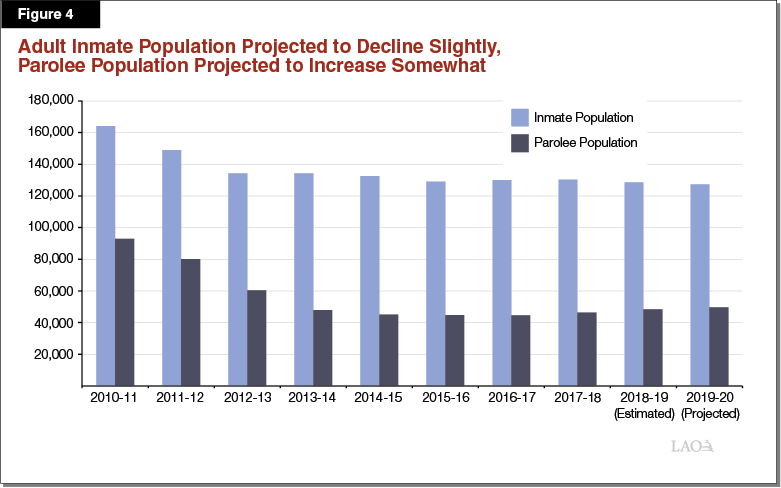

As shown in Figure 4, the average daily inmate population is projected to be 127,000 inmates in 2019‑20, a decrease of about 1,400 inmates (1 percent) from the estimated current‑year level. Also shown in Figure 4, the average daily parolee population is projected to be 50,000 in 2019‑20, an increase of about 1,200 parolees (3 percent) from the estimated current‑year level. The projected decrease in the inmate population and increase in the parolee population is primarily due to the estimated impact of Proposition 57 (2016), which made certain nonviolent offenders eligible for parole consideration and expanded CDCR’s authority to reduce inmates’ prison terms through credits.

Governor’s Proposal

As part of the Governor’s January budget proposal each year, the administration requests modifications to CDCR’s budget based on projected changes in the inmate and parolee populations in the current and budget years. The administration then adjusts these requests each spring as part of the May Revision based on updated projections of these populations. The adjustments are made both on the overall population of offenders and various subpopulations (such as inmates housed in contract facilities and sex offenders on parole).

The administration proposes a net increase of $17.3 million in the current year and a net increase of $16.4 million in the budget year for adult population‑related proposals. The current‑year net increase in costs is primarily due to a smaller than anticipated reduction in the use of contract beds, as well as increases in the number of offenders housed in state‑operated prisons and on parole relative to what was assumed in the 2018‑19 Budget Act. This increase in cost is partially offset by projected savings, primarily due to a reduction in custody staffing associated with the conversions of various housing units to lower security status. The budget‑year net increase in costs is primarily due to a projected increase in the parolee population as a result of Proposition 57. These increased costs are partially offset by savings—such as from a decrease in the use of contract beds.

LAO Assessment

Annual Population‑Related Requests Typically Do Not Account for Recent Policy Changes. In the fall and spring of every year, CDCR releases projections of the inmate and parolee populations that are used to make necessary funding adjustments for both the current and budget years. The projections are based on historical trend data and typically do not include the effects of very recent policy changes or those planned for the near future. This is because CDCR often does not have time to adjust projections for these changes or assumes that their effects would be minor. In certain circumstances, however, CDCR has occasionally adjusted its population projections to account for planned policy changes, such when Proposition 57 was implemented in 2017.

Several Policy Changes Currently Being Implemented Are Expected to Impact Correctional Population. In 2019‑20, several recent policy changes are anticipated to accelerate the release of certain inmates from prison. For example, the 2018‑19 Budget Act provided resources for CDCR to refer inmates to courts for possible sentence reduction due to sentencing errors or because of their exceptional behavior while incarcerated. In addition, we recently discovered that CDCR is in the process of using its authority under Proposition 57 to further increase credits inmates earn for participating in rehabilitative and educational activities starting in May 2019. (As we discuss below, the department is not currently required to notify the Legislature when it makes changes to its credit earning policies.) For example, CDCR plans to increase the number of days inmates earn off of their prison sentences for earning a high school diploma from 90 days to 180 days. As a result of these policy changes, the inmate population is expected to decline and the parolee population is expected to temporarily increase. Both of these estimated impacts are not reflected in CDCR’s current population projections. Given that the current population projections form the basis of the administration’s population‑related budget requests, it is possible that the requested level of resources may be more than the department will need.

Lack of Legislative Notification of Credit Changes Makes It Difficult to Account for Potential Population Impacts. Given the authority provided to CDCR under Proposition 57 to reduce inmates’ terms by awarding them credits for good behavior or participation in rehabilitative programs, CDCR will likely continue to make changes to credit policies that could significantly impact the inmate and parolee populations and the level of resources necessary to support them. We also note that changes to credits can have implications for sentencing, offender rehabilitation, public safety and other areas of interest to the Legislature. However, CDCR makes credit changes through the regulatory process, which means it is difficult for the Legislature to become aware of the changes in a timely manner. For example, as mentioned above, the Legislature was not directly notified of the department’s recent credit changes, despite the fact that these changes could affect the department’s resource needs.

LAO Recommendations

Require Population Projections and Budget Requests Account for Recent Policy Changes. We recommend that the Legislature require the administration to account for the estimated impact of the recent changes to credit policies and CDCR’s efforts to propose inmates for resentencing in its spring population projections and budget requests at the May Revision. Accounting for these recent policy changes would help the Legislature avoid approving resources for CDCR that it may ultimately not need. We withhold recommendation on the administration’s adult population funding request until the above information is provided.

Require Reporting When CDCR Makes Future Changes to Credits. We also recommend that the Legislature pass statute directing CDCR to report to the relevant fiscal and policy committees of both houses of the Legislature when it makes changes to credit policies in the future. This report should include an explanation of the rationale for the changes and estimates of the impact of the change on the inmate and parolee populations. This requirement would help ensure that the Legislature is aware of changes to credit policies when it considers CDCR resource needs and broader criminal justice policy matters in the future.

Board of Parole Hearings

Overview

The Board of Parole Hearings (BPH) within CDCR is currently composed of 15 commissioners. Along with deputy commissioners, they consider whether to grant parole to all persons sentenced to state prison under the state’s indeterminate sentencing laws, as well as certain determinately sentenced inmates who qualify for parole suitability hearings. (Under indeterminate sentencing, offenders receive a sentence range, such as 25‑years‑to‑life. Under determinate sentencing, offenders receive fixed prison terms with specified release dates.) They also determine (1) whether to impose any special conditions on offenders who are granted parole—such as requiring participation in certain rehabilitative programs—once they are in the community and (2) how long offenders who are denied parole must wait until their next parole hearing, which can range from 3 to 15 years. In addition, BPH advises the Governor on applications for clemency and approves transfers of foreign‑born inmates to their native countries.

The Governor’s budget proposes $61 million (primarily from the General Fund) for BPH operations in 2019‑20. This is an increase of $10 million, or about 19 percent, from the estimated 2018‑19 spending level. This increase is primarily due to an increase in the number of hearings that BPH is expecting to hold in 2019‑20.

Structured Decision‑Making Framework for Parole Hearings

We recommend that the Legislature require the BPH to provide key information about its proposal to implement a structured decision‑making framework that guides parole decision makers through the process of weighing information about an inmate. Specifically, we recommend that BPH provide information on the development, usage, and implementation of the framework by April 1, 2019. The board should also provide a prototype of the proposed framework for the Legislature to review. Pending receipt of the above information, we recommend that the Legislature withhold action on the Governor’s proposal.

Background. The purpose of a parole hearing is to determine whether an inmate is suitable for release or if he or she currently poses an unreasonable risk of danger to society. The hearing panel, which typically consists of one BPH commissioner and one deputy commissioner, considers many sources of information, including a risk assessment from a psychologist, statements from the inmate and victims, and records of the inmates’ behavior while incarcerated. Research indicates that some of the sources of information considered are better predictors of dangerousness than others. For example, risk assessments completed by psychologists are among the best predictors of dangerousness. While BPH regulations outline criteria that tend to indicate suitability for release (such as positive behavior while incarcerated) and unsuitability (such as an unstable social history), there is currently no prescribed framework that the panel is required to follow in making its decisions in granting parole. However, BPH attempts to ensure accuracy and consistency in decision‑making by providing panel members with ongoing training and periodic legal feedback regarding their parole hearing decisions.

Since 2011, BPH has scheduled between 4,000 and 5,300 parole hearings annually. Beginning in 2019‑20, however, the board estimates that the number of hearings will increase significantly. This is primarily due to (1) recent legislation—Chapter 475 of 2015 (SB 261, Hancock) and Chapter 675 of 2017 (AB 1308, Stone)—granting parole hearings to offenders who committed crimes in their youth and (2) the requirement that BPH consider granting parole under Proposition 57 to indeterminately sentenced inmates convicted of nonviolent crimes. Specifically, the board estimates that there will be a total of 7,200 parole hearings in 2019‑20 and 8,300 hearings in 2020‑21. BPH expects its workload to continue to remain high in subsequent years.

Governor’s Proposal. In order to accommodate the anticipated increase in parole hearings, the Governor proposes to:

- Reduce Staff Time on Hearings by Implementing Structured Decision‑Making Framework. A structured decision‑making framework is a tool that consistently and systematically guides parole decision makers through the process of weighing information about an inmate that research demonstrates either aggravates or mitigates the inmate’s risk of future violence. For example, the parole board in Pennsylvania uses a framework that combines the results of several actuarial risk assessments and inmates’ institutional behavior and programming history into a numerical score, yielding a parole recommendation that commissioners can supplement with their qualitative observations. BPH indicates that a structured decision‑making framework would reduce the amount of time commissioners and deputy commissioners spend preparing for and participating in hearings. The Governor’s budget assumes that the board will implement the framework on July 1, 2019. The board indicates that it will receive technical assistance from the National Institute of Corrections (NIC) in implementing the framework. We note that the Governor’s budget does not include additional resources for BPH to develop and implement the framework.

- Increase Resources to Allow BPH to Conduct Additional Hearings. BPH expects that implementation of the framework will allow it to process more hearings with existing resources. However, given the large increase in hearings anticipated in 2019‑20, BPH indicates that it will still need additional resources to process this workload. As such, the Governor’s budget proposes an increase of $4.9 million (General Fund) and 13.5 positions in 2019‑20. Under the proposal, the level of funding would increase to $6.3 million in 2020‑21 and decline to $2.1 million in 2021‑22 and annually thereafter. According to BPH, these additional resources would allow it to add two parole commissioners, pay for additional support staff, and make IT upgrades.

Proposal Has Merit, but Insufficient Information Provided. Based on existing research, we find the proposed use of a structured decision‑making framework to be promising. This is because it could improve public safety if it increases the ability for hearing panels to focus on factors shown to be associated with risk. Furthermore, the proposed framework could improve efficiency, transparency, and consistency of the board’s parole decision‑making process. However, BPH has not provided a prototype of the framework or provided important details on its process for developing, implementing, and evaluating the framework. The absence of such information makes it difficult for the Legislature to effectively evaluate this potentially significant policy change.

Specifically, the proposal lacks basic information on the following key questions:

- What Is the Process for Developing the Framework? It is unclear how BPH will develop the decision‑making framework. For example, it is unclear what sources of information BPH is using to develop it and when it is expected to be finished.

- How Will the Framework Be Used? At this time, it is unclear whether the framework would solely guide commissioners in considering whether to release an inmate or whether it will would also assist in their decisions about (1) what conditions to impose on offenders who are released or (2) how long inmates who are not released must wait for their next hearing.

- How Will the Framework Be Implemented? While BPH indicates that NIC will provide technical assistance in the implementation of the framework (including site visits from experts), the board has not provided a detailed implementation plan. For example, it is unclear what training will be provided to commissioners and deputy commissioners in how to use the framework or what processes BPH will use to ensure it is ultimately applied consistently as intended.

- How Will the Framework Be Evaluated? It is unclear on the extent to which the framework would be evaluated to ensure it is consistent with best‑practices, as well as its impact on rates of inmate release and re‑offense. In addition, it is uncertain whether BPH will periodically evaluate the framework in the future to ensure it remains consistent with evolving research and best practice on criminal risk factors.

Assuming BPH is able to successfully implement the framework in July 2019, the resources requested to process the increase in hearings appears reasonable. However, if BPH is not able to do so or the framework does not reduce workload at the level assumed under the Governor’s proposal, the Legislature may need to provide additional resources to allow BPH to process its full workload in 2019‑20. Accordingly, it is important that the Legislature receive a detailed plan for the development and implementation of the framework. In addition, in order to facilitate effective legislative oversight, BPH should provide a prototype of the framework and detailed information about how it plans to evaluate the framework.

LAO Recommendation. In view of the above, we recommend that the Legislature require BPH to provide key information about the proposed structured decision‑making framework (such as in regards to its development, usage, and implementation) by April 1, 2019. The board should also provide a prototype of the proposed framework for the Legislature to review. Pending receipt of the above information, we recommend that the Legislature withhold action on the Governor’s proposal.

Compensation for Attorneys Appointed by BPH

We recommend that the Legislature require the administration to provide key information about the proposed changes to the attorney pay schedule by April 1, 2019. Pending receipt of this information, we recommend that the Legislature withhold action on the Governor’s proposal. If the administration is unable to provide this information, we recommend rejecting the proposal and directing the administration to provide a revised proposal with adequate information as part of the 2020‑21 budget process.

Background. Many inmates cannot afford to hire an attorney to represent them in parole hearings. In these cases, BPH appoints and pays for their attorneys. BPH currently contracts with about 36 attorneys to represent inmates in parole hearings throughout the state, with each attorney handling roughly 150 cases per year on average. As shown in Figure 5, BPH currently pays attorneys a flat rate for completing a specific task in the parole hearing process. Depending on the nature of the case, an attorney may not ultimately complete all tasks. For example, inmates have the option to waive their right to a parole hearing for one to five years or to stipulate that they are unsuitable for parole for a minimum of three years. (Inmates do this for a variety of reasons, including potentially being released from prison earlier than if they went to a hearing but were denied parole and required to wait 15 years until their next hearing.) In this example, there would be no hearing and, thus, the attorney would not receive the $175 payment. BPH estimates that on average, attorneys receive $400 per case.

Figure 5

Board of Parole Hearings Attorney Pay Structure

As of February 1, 2019

|

Task |

Payment |

|

Appointment to a case |

$25 |

|

Review case information, document inmate disability needs, conduct legal research |

50 |

|

Review inmate’s file |

75 |

|

Interview inmate |

75 |

|

Appear at parole hearing |

175 |

|

Appear at full board meetinga |

100 |

|

Prepare written submission for full board meeting |

50 |

|

aCases only go to full board meetings in rare circumstances, such as if there is disagreement among the hearing panel about whether or not to grant parole. |

|

In recent years, BPH indicates that it has had trouble attracting and retaining competent attorneys and has had to reprimand or even discontinue appointing some attorneys for providing inadequate representation to their clients. According to the board, this is because attorney pay has not kept up with the increasing amount of work that attorneys must do on each case—largely due to more requirements related to documenting inmates’ disability accommodation needs. The board also indicates that the current pay structure may discourage stipulations and waivers of parole hearings. This is because attorneys receive a relatively significant increase in compensation if a case proceeds to the hearing stage.

Governor’s Proposal. In view of the concerns expressed about the current attorney pay schedule and its impact on the ability of the board to attract and retain competent attorneys, the Governor proposes to budget BPH at $750 per hearing, rather than $400 per hearing as is the current practice. Accordingly, the Governor’s budget proposes a $2.5 million General Fund augmentation for BPH in 2019‑20. In addition, BPH proposes to restructure the attorney pay schedule, modify its attorney recruitment process, provide additional attorney training, and increase attorney expectations.

New Pay Structure Appears Needed, but Proposal Lacks Key Details. We find that problems cited by BPH regarding the current attorney pay schedule could potentially result in serious consequences—particularly if inmates lack appropriate representation in parole hearings. First, to the extent that poor representation results in fewer inmates being granted parole or in inmates being given longer denial periods, inmates could spend more time in prison—at higher state cost—than otherwise. Second, to the extent that the current pay structure discourages stipulations and waivers, it could generate unnecessary hearings—an unnecessary use of state resources—and/or result in inmates having to wait longer until their next parole hearing than they would have if they had waived their right to a hearing or stipulated that they were unsuitable for parole.

We note, however, that the Legislature currently lacks sufficient information to effectively evaluate the Governor’s proposal. This is because the proposal lacks basic information on the following key questions:

- What Is the Basis for the Proposed $750 Payment? At the time of this analysis, BPH was unable to provide a workload study—or other form of adequate explanation—to justify the proposed $750 per case for attorney pay. Without this information, the Legislature cannot assess whether the proposed $750 per hearing is the appropriate amount to attract and retain high quality attorneys.

- What Is the Structure of the New Pay Schedule? BPH has not provided the proposed pay structure. Accordingly, it is unclear whether the new schedule would appropriately incentivize attorneys to provide adequate representation to inmates.

- What Changes to Attorney Recruitment, Training and Expectations Are Proposed? BPH has not provided specific details about the planned changes to attorney recruitment, training and expectations. Furthermore, it is unclear how BPH would identify and respond to attorneys who do not meet the new expectations. As such, it is unclear whether implementation of these changes will be effective, as well as whether the board will require additional resources to implement them.

LAO Recommendation. In view of the above concerns, we recommend that the Legislature require the administration to provide the key information about the proposed changes to the attorney pay schedule by April 1, 2019. Pending receipt of this information, we recommend that the Legislature withhold action on the Governor’s proposal. If the administration is unable to provide this information, we recommend rejecting the proposal and directing the administration to provide a revised proposal with adequate information as part of the 2020‑21 budget process.

Inmate Literacy

While the Governor’s proposal to establish a literacy mentorship program could improve inmate literacy, its actual effectiveness at improving literacy and educational attainment is unclear. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature approve the proposed program as a three‑year pilot—rather than as an ongoing program as proposed by the Governor. Due to potential unintended consequences of mandating criminal personality therapy for all inmate mentors, we also recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to require that inmate mentors complete criminal personality therapy only if they have a moderate or high need for such therapy.

Background

Education and Literacy Are Core Parts of CDCR’s Rehabilitation Focus. Under current state law, CDCR is required to improve inmate literacy and educational attainment. Improving inmate literacy and educational attainment is important because research shows that education programs, when appropriately implemented, are a cost‑effective method of reducing recidivism. Moreover, it is often necessary for inmates to improve their literacy in order to be able to effectively participate in other rehabilitation programs while in prison, such as vocational or cognitive behavioral therapy programs.

The 2018‑19 Budget Act provided about $154 million (mostly from the General Fund) to CDCR for various inmate academic education programs. Some of these programs include literacy education that is provided in different settings. For example, classroom‑based literacy education consists of classes of up to 27 inmates who meet for roughly 16 hours a week. Under this program, an instructor can work with up to 54 inmates. The department also operates the Voluntary Education Program, which is designed to supplement classroom based education or to provide access to education when a classroom based option is not available. An instructor in this program can work with up to 120 inmate students—offering in‑person support at least twice a week but with no hourly attendance requirements. In addition, CDCR provides technology based education such as computer software designed to help develop basic literacy. As of December 2018, the above academic education programs served about 26,000 inmate literacy students daily.

Despite Efforts, Inmate Literacy and Educational Attainment Remain Low. The department measures inmate literacy and educational attainment by administering the Test for Adult Basic Education (TABE) to inmates. An inmate’s score on the test indicates the grade level at which they are able to read and is used to help prioritize inmates for placement in education programs. The department has a statutory responsibility to focus on improving the reading ability of inmates to at least a 9th grade level. However, as of December 2018, about 53,000—or 47 percent—of inmates read below the 9th grade level. Given that the existing literacy programs support 26,000 inmates, there are likely tens of thousands of inmates reading below the 9th grade level who are not receiving literacy instruction. This could be attributed to a variety of reasons. For example, the department indicates that some inmates have assignments (such as jobs within the prison) that conflict with class schedules.

Governor’s Proposal

Provide Funding to Establish New Literacy Mentorship Program. The Governor’s budget proposes $5.5 million from the General Fund in 2019‑20—decreasing to $5.4 million in 2020‑21 and annually thereafter—for CDCR to implement an inmate literacy mentorship program. This amount includes (1) $4.3 million to support 35 permanent academic instructors (one per prison) to create, maintain, and facilitate the program and (2) $1.1 million to compensate the inmates who participate in the program as mentors.

Utilize Inmate Mentors to Tutor Other Inmates. CDCR expects the proposed mentor program to improve literacy levels by increasing access to literacy education, leading to higher TABE scores and high school diplomas/equivalencies. Under the proposed program, each instructor would train 20 inmate literacy mentors beginning in July 2019. Each inmate mentor would then provide literacy tutoring to up to 20 inmate students. According to the department, this approach would essentially increase the reach of the instructors to 400 inmate students. In addition, CDCR indicates that inmate mentors would have the flexibility to provide tutoring at various locations and times, which could improve access for inmates who may not otherwise attend literacy programs due to conflicting assignments or work opportunities.

Require Inmate Mentors to Participate in Training Program. Inmate mentors would complete a three part training program, including an internship component. In addition, prior to or as part of training, inmate mentors would be required to complete criminal personality therapy—regardless of whether they have been assessed to have a moderate or high need for the therapy. Following the completion of the training, inmate mentors would be offered a full‑time work assignment (six hours a day) paying $0.85 to $1.00 per hour to mentor inmate students seeking to improve their literacy.

LAO Assessment

Program Could Improve Literacy but Actual Effectiveness Remains Unclear. We find that the Governor’s proposal merits legislative consideration as it could be a relatively low‑cost way of expanding literacy education to additional inmates. However, students would only receive an average of 90 minutes of support from inmate mentors per week. While this would likely be higher than the Voluntary Education Program, it is far lower than the roughly 16 hours of instruction offered in the traditional classroom model. Furthermore, it is unclear how effective inmate mentors would be at improving inmate students’ literacy and educational attainment relative to instructors. This is because there is little research available regarding the effectives of similar inmate mentor programs. These factors raise questions about whether the effect of this program would be large enough to justify its costs.

Program Would Benefit Inmates Beyond the Impact on Literacy. In addition to any improvements in literacy, inmates who receive tutoring services would receive rehabilitative achievement credits for the time they spend with inmate mentors. We estimate that such inmates could earn an average of roughly a couple weeks of credit annually through the program. Inmate mentors would also benefit from the program. Over the course of the required mentorship training, inmate mentors could earn up to six weeks of milestone completion credits and an additional 90‑day educational merit credit. We also note that the proposed pay rate for inmate mentors of $0.85 to $1.00 per hour is competitive with the high end of the pay scale for other inmate work opportunities, such as those offered through the California Prison Industry Authority (CalPIA).

Requiring All Mentors to Take Criminal Personality Therapy Could Have Unintended Consequences. In 2017‑18, about 41 percent, or about 44,000, of assessed offenders were found to have a moderate to high need for criminal personality therapy. This suggests that many of the inmate mentors could have a low need for the therapy but would nevertheless be required to receive such therapy under the Governor’s proposal. This is problematic for two reasons. First, requiring such therapy for prospective mentors who do not have a moderate to high need would increase the time it takes to train them, and as a result, delay when inmate students could begin receiving literacy tutoring. Second, there could be unintended consequences depending on how potential inmate mentors are prioritized for therapy. For example, if the mentors are prioritized over other inmates, it could prevent offenders with a greater need for the therapy from being able to enroll in it. This is especially problematic given that, as of June 2018, CDCR only had the capacity to provide criminal personality therapy to 9,840 offenders, or about 28 percent of those who have a moderate to high assessed need.

Funding Does Not Account for Training. As mentioned above, the proposal includes $1.1 million to provide a full year of pay to inmate mentors beginning in July 2019. However, based on the proposed training plan, it would take a minimum of eight months, or at least until March 2020, before an inmate completed training and began receiving wages—suggesting that no more than $367,000 in inmate mentor wages would be needed in the first year of implementation.

LAO Recommendations

Approve Proposed Program on a Pilot Basis. Given that it is unclear how effective inmate mentors would be at improving literacy and educational attainment, we recommend that the Legislature approve the proposed inmate literacy mentorship program as a three‑year pilot—rather than as an ongoing program as proposed by the Governor. Specifically, we recommend that the Legislature approve $700,000 in 2019‑20, $800,000 in 2020‑21 and 2021‑22, and five instructors on a three‑year, limited‑term basis. This would allow the department to implement an inmate literacy mentorship pilot with up to 100 inmate mentors and 2,000 students across five different prisons. (We note that this level of resources would account for the time it takes to train inmate mentors before they are paid.)

We also recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to select participating prisons that would reflect the larger system, particularly in regards to security levels and missions. In addition, we recommend that the Legislature require CDCR to report by January 10, 2022 on the effect that the program has on inmate students’ TABE scores relative to similar inmates who are enrolled in traditional education programs, as well as those who lack access to traditional educational programs. This would help the Legislature determine whether the program’s effects on inmate literacy and educational attainment is large enough to justify funding the program on an ongoing basis in the future.

Remove Criminal Personality Therapy Requirement Unless Mentors Have Moderate to High Need. Due to the potential negative impacts of mandating criminal personality therapy for inmate mentors, we recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to require that inmate mentors who participate in the pilot complete criminal personality therapy only if they have a moderate or high need for the therapy.

Tattoo Removal Program

We recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to provide additional information regarding the Governor’s proposed tattoo removal program by April 1, 2019, in order for the Legislature to effectively evaluate the proposal. Specifically, the administration should report on (1) who would be eligible for the program, (2) how many inmates are anticipated to need or want the service, (3) how eligible and interested inmates would be prioritized, (4) how the service would be delivered, and (5) how the program would be evaluated. If the administration is not able to provide sufficient information, we would recommend the Legislature reject the proposal.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget proposes a $2.5 million General Fund augmentation in 2019‑20 for CDCR to establish a tattoo removal program that would be available at all state prisons. CDCR estimates that the proposed level of funding would be sufficient to remove the tattoos of 4,300 inmates annually (about 3 percent of the average daily inmate population). According to the administration, it is proposing a tattoo removal program for two reasons. First, research suggests that certain tattoos, particularly those that are hard to cover up and/or indicate a gang affiliation, are associated with an increased risk of recidivism and could make it difficult for inmates to find employment following their release from prison. Second, the administration intends to assist inmates who are leaving gangs but still have gang‑related tattoos. If such inmates had their tattoos removed, the administration believes that they would be less likely to rejoin their gangs or be victimized than otherwise would be the case.

We note that as of 2018, the CalPIA—a semiautonomous state agency that provides work assignments and vocational training to inmates—provides tattoo removal services for some of its female inmate workers. In addition, the DJJ within CDCR offers tattoo removal services to the youth in its facilities using two state‑owned machines. Tattoo removal is provided upon request, however, DJJ prioritizes which youth will receive the service based on the date the youth is expected to return to the community.

Proposal Lacks Key Information

A tattoo removal program could result in certain benefits—such as better employment prospects for inmates that receive the service and reduced recidivism. However, the Governor’s proposal lacks key pieces of information, which makes it very difficult for the Legislature to assess whether the proposed program would be effective and whether the requested funding is appropriate or if a different amount is necessary.

Specifically, the Governor’s proposal lacks basic information on the following aspects of the proposed program:

- Who Would Be Eligible. The administration has not been able to specify the pool of inmates who would be eligible for the program. For example, it is not clear if the program would be limited to inmates with tattoos that are hard to cover up and/or indicate a gang affiliation or if all inmates with a tattoo would be eligible. We also note that removing a tattoo is a lengthy process that could take several months to a year to complete. It is unclear if the program would be limited to inmates who are far enough from release to complete the tattoo removal process. In not, some inmates could be released from prison with only having their tattoos partially removed.

- How Many Eligible Inmates Want Tattoos Removed. Once eligibility criteria has been established, it remains unclear how many eligible inmates would in fact want their tattoos removed and whether this amount is more or less than the 4,300 inmates the administration estimates it could serve annually with the requested funding. Without this information, it is difficult for the Legislature to determine whether the proposed $2.5 million is the right amount to support the program.

- How Eligible Inmates Who Want the Service Would Be Prioritized. To the extent more eligible inmates are interested in having their tattoos removed annually than resources allow, it is unclear how the department would prioritize certain inmates over others. For example, it is unclear whether CDCR would prioritize inmates with gang‑related tattoos, and/or if other factors—such as time left before release—would be considered. Not knowing how the department would select inmates from among those eligible for the program, makes it difficult to assess whether the program’s resources would be targeted appropriately.

- How Service Would Be Delivered. At this time, there is limited information available on how the program’s service would be delivered to inmates. For example, it is not clear if CDCR would use state staff or private contractors to remove tattoos. It is also unclear if the department plans to maintain tattoo removal equipment at each prison or if it plans to use mobile equipment to provide services at multiple facilities. We note that the CalPIA’s tattoo removal program is a contracted mobile service while the DJJ program uses state‑owned machines located at two of its three facilities. The structure of the proposed program could significantly impact the upfront or ongoing costs of the program. For example, if CDCR chooses to purchase equipment, as DJJ did, then there would likely be higher upfront costs that would decline somewhat in future years.

- How the Program Would Be Evaluated. It also unclear whether or how the program would be evaluated for its effectiveness. Without an evaluation, it would be difficult for the Legislature to assess whether this program should continue or be modified in the future.

While the Governor’s proposal currently lacks the above information needed for the Legislature to effectively assess its merits and viability, our understanding is that the administration is in the process of restructuring the proposal and plans to provide additional details about the proposed program this spring.

LAO Recommendations

In view of the above, we recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to provide additional information regarding the proposed tattoo removal program. Specifically, the administration should report on (1) the criteria that will be used to determine inmate eligibility, (2) the estimated number of eligible inmates who would be interested in removing their tattoos (including the assumptions behind this estimate), (3) how eligible and interested inmates would be prioritized if sufficient resources are unavailable, (4) how the tattoo removal service would be delivered, and (5) a plan for how it would evaluate the cost‑effectiveness of the program at reducing recidivism. In order to ensure that the Legislature has sufficient time to consider the above information in its budget deliberations, we recommend that the administration provide the information by April 1, 2019. To the extent that the administration is not able to provide information on the key aspects of its proposal by that time, we would recommend the Legislature reject the proposal.

DJJ Partnership with California Volunteers

We recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to provide detailed justification for the $2 million in ongoing General Fund support proposed to implement a new mentorship program for juvenile offenders. Until such information is provided by the administration, we recommend that the Legislature withhold action on the Governor’s proposal. To the extent that the administration is unable to justify the level of funding requested—specifically the funding for training, travel, supervision, and administration costs—we recommend the Legislature only approve $667,000 from the General Fund for three years to align with the AmeriCorps grant process and be consistent with the potential level of need currently identified by DJJ.

Background

Honorable Discharge. Chapter 683 of 2017 (SB 625, Atkins), reestablished an honorable discharge process for former wards of DJJ. (The previous honorable discharge process was effectively eliminated when responsibility for supervising DJJ parolees was shifted—or realigned—from the state to county probation departments in 2010.) Under this process, the Board of Juvenile Hearings—which also determines when wards are released from DJJ—has the authority to grant honorable discharge to former DJJ wards who have demonstrated their ability to refrain from criminal behavior and initiate a successful transition to adulthood. To qualify for honorable discharge, former wards must wait at least 18 months from their discharge from DJJ custody and must have completed any required periods of probation supervision. Individuals can petition for honorable discharge regardless of whether they were released from DJJ custody prior to or following the reestablishment of honorable discharge. In 2018, the board only received six complete applications and only awarded three honorable discharges.

The state offers honorable discharges to youth for several reasons. These include recognizing and rewarding youth who have avoided reoffending, removing barriers to a youth’s successful integration into society, and providing an incentive for youth to participate in treatment and training while placed in DJJ. In addition, receiving an honorable discharge can be used as evidence of rehabilitation, which is one of the requirements for sealing a juvenile adjudication—meaning the case would be deemed to have never occurred and access to the records would generally be restricted.

AmeriCorps. AmeriCorps is a national service program that provides year‑long volunteering opportunities to address critical community needs. AmeriCorps volunteers can receive a small living allowance while in the program. Upon completion of the program, volunteers are eligible to receive a monetary Segal AmeriCorps Education Award from the federal government, which can be used to pay for higher education expenses or help pay off qualified student loans. In addition, AmeriCorps provides grants to support volunteer programs administered by states or other entities.

CaliforniaVolunteers. CaliforniaVolunteers is a non‑profit entity housed within the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research. It administers $40 million annually in federal AmeriCorps grants in support of programs in California such as programs aimed at disaster preparedness and recovery, connecting homeless individuals to resources, and providing assistance at self‑help legal centers.

Governor’s Proposal

Establish Mentorship Program to Increase Honorable Discharges. The administration proposes to create a mentorship program utilizing 40 half‑time AmeriCorps volunteers to help increase the number of former DJJ wards who receive honorable discharge. Under the proposal, the AmeriCorps volunteers would coach and mentor youth currently or formerly housed in DJJ in an attempt to increase the youths’ ability to receive honorable discharges by (1) helping them navigate the honorable discharge process and (2) encouraging them to utilize reentry resources provided by community‑based nonprofit and public organizations, such as case management, job skills training, and referrals to other rehabilitative resources and opportunities.

The AmeriCorps volunteers would be chosen from applicants with prior involvement in the criminal justice system, either in the form of a juvenile adjudication or adult incarceration. The volunteers would receive training to improve skills relevant to their positions including leadership, motivational interviewing, and life coaching certifications. Upon completing their terms of service, volunteers would be eligible for Segal AmeriCorps Education Awards of about $3,000.

Provide Funding for Partnership With CaliforniaVolunteers to Support Program. The Governor’s budget for 2019‑20 proposes $2 million from the General Fund to implement the proposed mentorship program on an ongoing basis. In addition, CaliforniaVolunteers has set aside $900,000 in federal AmeriCorps grant funds to be spent over three years (from 2019‑20 through 2021‑22) to support the program. We note that after 2021‑22, the availability of AmeriCorps funding for the program—and the program’s AmeriCorps affiliation—would depend on the grant being renewed by AmeriCorps for another three years.

The proposed funding would provide living allowances of $14,815 to the 40 half‑time AmeriCorps volunteers at a total annual cost of about $600,000. According to the administration, any remaining funding—roughly $1.7 million per year, or 74 percent of available funds—would support training, travel, supervision, and administration costs.

LAO Assessment

Proposed Mentorship Program Could Have Merit . . . The Governor’s proposal could increase honorable discharges and improve outcomes to the extent that it effectively expands outreach to youth, facilitates connections between youth and reentry services, and provides peer mentorship. Accordingly, we find that the proposal merits legislative consideration.

. . . But Proposed Funding Not Fully Justified. The administration has not fully justified the need for the proposed $2 million in annual General Fund support—both in terms of the amount and the ongoing nature of the funding. Specifically, the administration has not provided detailed workload justification for the $1.7 million that would support training, travel, supervision, and administration. We note that the proposed funding set aside for these costs would amount to $42,500 per volunteer. By comparison, the living allowance that each volunteer would receive is only $14,815. Moreover, DJJ states that in order to implement the program, it may only need $667,000 per year in General Fund rather than the proposed amount of $2 million.

We also note that the Governor’s proposal to provide ongoing funding assumes that the federal AmeriCorps grant will be renewed after the grant’s three‑year cycle ends in 2021‑22. Given the uncertainty on whether the grant will in fact be renewed, it would make more sense to provide General Fund support on a three‑year basis to track with the time frame of the AmeriCorps grant. The administration states that it may revise the amount requested in the spring budget process once it has a better understanding of the workload and necessary funding.

LAO Recommendations

We recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to provide detailed justification for the $2 million in ongoing General Fund support proposed for the new mentorship program. Until such information is provided by the administration, we recommend that the Legislature withhold action on the Governor’s proposal. To the extent that the administration is unable to justify the level of funding requested—specifically the funding for training, travel, supervision, and administration costs—we recommend the Legislature only approve $667,000 from the General Fund for three years to align with the AmeriCorps grant process and be consistent with the potential level of need currently identified by DJJ.

Vehicle Replacement Schedule

We recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to estimate the maintenance, repair, and fuel savings as well as the increase in auction revenue that it would generate by implementing the proposed vehicle replacement program so that the department’s overall budget can be adjusted to account for these savings. If the department is able to demonstrate that these savings would occur, we recommend approving the requested funds in a separate budget item to prevent them from being redirected for other purposes.

Background

CDCR Uses Vehicles for Various Purposes. CDCR owns nearly 7,700 vehicles of varying types (ranging from golf carts to farming equipment) that are used for a variety of purposes, including inmate transportation (both within and outside of prison grounds), fire protection, construction support, and institution perimeter security. CDCR staff and inmate workers generally maintain the department’s vehicles. However, they are sometimes sent out for more complex repairs.

Department of General Services (DGS) Sets Vehicle Replacement Thresholds. DGS sets policy for and approves all state vehicle purchases. Specifically, DGS sets replacement thresholds for different types of vehicles that, if met, make a vehicle eligible for replacement. For example, a sedan that either has over 65,000 miles or is older than six years is eligible for replacement. In determining the vehicle replacement thresholds, DGS hired a consultant in 2016 to estimate the age and mileage levels at which it is more cost‑effective to replace various types of vehicles rather than repair them, based on actual data on state vehicle price, operational cost, and resale value. By replacing vehicles according to these thresholds, DGS expects that departments would minimize the total costs of the state’s vehicle fleet. Currently 5,500 of CDCR’s 7,700 vehicles exceed DGS’s thresholds for replacement.

CDCR Does Not Have Ongoing Funding Specifically for Vehicle Replacement. CDCR’s baseline budget does not include ongoing funding dedicated to vehicle replacement. The Legislature has on occasion provided one‑time funding for the department to purchase vehicles. For example, the 2018‑19 budget provided CDCR with $17.5 million in one‑time General Fund support to replace 338 vehicles that are used for transporting inmates to health care and other appointments. Historically, the department has also used some of the funding it has budgeted for major equipment purchases—currently set at $8 million—to purchase vehicles, as well as redirected funding originally intended for other purposes. In addition, when CDCR replaces a vehicle, the old vehicle is sold at auction, with revenue generated—typically in the low hundreds of thousands of dollars annually—used to offset the costs of future vehicle purchases. In total, CDCR spent roughly $15 million per year on vehicle purchases between 2013‑14 and 2017‑18.

Governor’s Proposal

Proposes Ongoing Funding to Establish Vehicle Replacement Program. The Governor’s budget proposes $24 million from the General Fund and four positions in 2019‑20 and ongoing for CDCR to establish a vehicle replacement program. In addition, the Governor proposes to permanently redirect the $8 million that CDCR currently dedicates to major equipment purchases to be spent solely on vehicles, bringing the total annual funding for the vehicle replacement program to $32 million. The amount of vehicles purchased in each year would depend on the actual types of vehicles being replaced, as some vehicle types cost significantly more than others.