LAO Contacts

- Edgar Cabral

- California Community Colleges

- Jason Constantouros

- University of California

- Lisa Qing

- California Student Aid Commission

- Paul Steenhausen

- California State University

February 21, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

Higher Education Analysis

- Introduction

- California Community Colleges

- California State University

- University of California

- California Student Aid Commission

- Summary of Recommendations

Executive Summary

In this report, we analyze the Governor’s higher education budget proposals. Below, we highlight key messages from the report.

California Community Colleges

Opportunities Exist for Improving Student Success Component of New Apportionment Formula. The Governor is concerned about the quality of student outcome data and initial increases in formula costs. In response, he proposes to (1) postpone for one year the scheduled increase in the share of funding linked to student outcomes and (2) cap annual growth in this part of the formula at 10 percent. We recommend adopting the postponement but rejecting the proposed growth cap, as it could dampen districts’ efforts to make genuine improvements in their student outcomes. We recommend exploring more targeted options, such as linking outcome‑based funding to the highest award a student earns. To address regular year‑to‑year fluctuations in student outcome data, we also recommend using a three‑year rolling average for funding purposes.

Recommend Rejecting Governor’s Proposal to Expand California College Promise Program. The Governor proposes to increase College Promise funding by $40 million. This proposal would allow community colleges to waive two years of enrollment fees for nonfinancially needy students enrolled full time or use the funds for various student support purposes. We have three concerns with the proposal. First, expansion is premature, as data on how the program is affecting students is not yet available. Second, while College Promise is intended to incentivize community colleges to improve student outcomes, the state now has other programs that create much stronger incentives to improve. Third, waiving fees for students without financial need might be a lower priority for the Legislature, given the remaining unmet need of other students. We recommend the Legislature reject the proposal and use the $40 million for higher Proposition 98 priorities.

Universities

Compensation Decisions Are a Key Part of University Budgets. The largest of the Governor’s proposed augmentations for the California State University (CSU) and University of California (UC) are increases in employee salaries and benefits. The Governor’s budget, however, supports increases for all CSU employees whereas it supports increases only for represented employees at UC. We encourage the Legislature to consider the extent to which the segments are attracting and retaining employees when evaluating CSU’s and UC’s compensation decisions.

Several Factors to Consider When Setting Enrollment Targets. The Governor proposes $62 million to fund 2 percent enrollment growth at CSU in 2019‑20 but sets no enrollment target for UC. The Legislature could consider several factors when setting enrollment targets. On the one hand, the number of high school graduates is projected to decline slightly the next couple of years. Both segments also are drawing from beyond their traditional freshman eligibility pools. On the other hand, many eligible applicants at both segments are not admitted to their preferred campus. Whereas the first two factors suggest the Legislature might wish to hold enrollment flat, the last factor suggests some growth might be warranted.

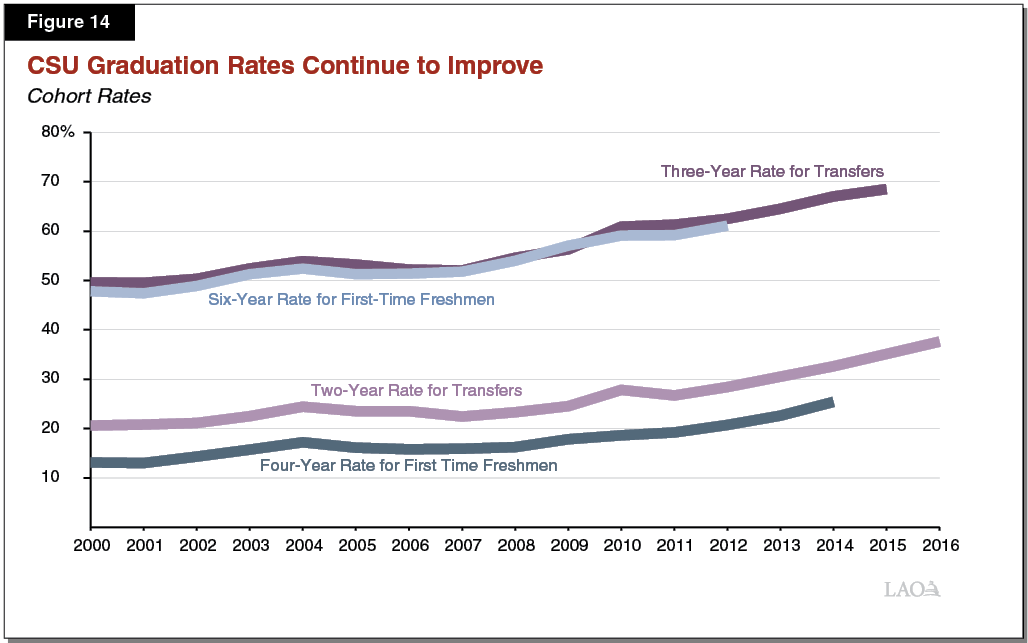

Recommend Increasing Transparency and Accountability for Student Success Initiatives. The Governor proposes funding student success initiatives at both segments ($45 million for CSU’s Graduation Initiative and $50 million for a new UC initiative). Were the Legislature interested in supporting these initiatives, we recommend linking the funding to the segments achieving certain performance expectations (such as improving graduation rates, reducing excess units, and narrowing achievement gaps by specified amounts).

Many Proposed Capital Outlay Projects Have Merit, but Some Not Justified. We have concerns with 4 of CSU’s 18 proposed projects and 2 of UC’s 7 proposed projects. We have concerns when projects are especially costly without justification, when the space requested is not warranted given existing facility utilization, and when promising, less costly alternatives exist. We recommend the segments not proceed with these six projects, though the segments could resubmit project proposals if they found ways to lower costs or better substantiate need.

Opportunities Exist for Making Tuition More Predictable. The Governor calls for more fiscal predictability for students and their families. The best way to promote such predictability is through sizeable state reserves—sufficient to sustain university spending during an economic downturn and prevent steep tuition hikes. One way to free up General Fund for higher reserves is to have student tuition cover a share of proposed 2019‑20 cost increases. In tandem with building higher reserves, we encourage the Legislature to adopt a policy explicitly establishing what share of cost nonfinancially needy students should pay. Such a policy would improve budget transparency and aim to treat student cohorts similarly, whether enrolling in college during good or bad economic times.

Cal Grants

Recommend Rejecting Proposal to Increase Financial Aid for Student Parents. The Governor proposes $122 million to help some financially needy student parents attending the three public segments with more of their living costs. We have several concerns with this proposal. By creating new rules that apply only to one group of students, the proposal further complicates the state’s financial aid system. By allocating additional aid based on students’ parental status rather than financial need, the proposal does not necessarily prioritize the highest‑need students. By focusing only on existing Cal Grant recipients, the proposal would not benefit most financially needy student parents, who do not currently receive Cal Grants because of the limit on available awards. We recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal but potentially pursue more information on this issue. To this end, it could request certain state agencies work with the segments to assess the extent to which current financial aid and public assistance programs collectively address student parents’ needs.

Recommend Prioritizing Funding for More Cal Grant Competitive Awards. The state currently provides up to 25,750 new competitive awards each year for students who do not qualify for an entitlement award (typically older students). The Governor proposes $9.6 million to fund an additional 4,250 awards. Because the number of eligible applicants far exceeds the number of competitive awards, each year nearly 300,000 financially needy students do not receive an award. Given this figure, we think increasing the number of competitive awards is warranted. If the Legislature wishes to go further, we estimate every $1 million augmentation funds 440 additional awards.

Introduction

In this report, we analyze the Governor’s major higher education budget proposals. The report has sections covering the Governor’s major proposals for the California Community Colleges (CCC), California State University (CSU), University of California (UC), and California Student Aid Commission. The final section of the report consists of a summary of our recommendations. Forthcoming analyses will cover Hastings College of the Law as well as a few other higher education proposals, including ones relating to student food and housing insecurity. For background on the state’s college students, staffing, campuses, funding, outcomes, and facilities, please see our recently released report, California’s Education System: A 2019 Guide. For tables providing additional higher education budget detail, please see the “EdBudget” section of our website.

California Community Colleges

In this section, we provide an overview of the CCC budget, then analyze the Governor’s proposals for community college apportionments, the College Promise program, and CCC facilities.

Overview

Total CCC Budget Reaches $15.9 Billion Under Governor’s Budget. Community colleges receive their core support from Proposition 98 funds (Figure 1). In addition, the state provides CCC with non‑Proposition 98 General Fund for certain purposes. Most notably, non‑Proposition 98 funds cover debt service on state general obligation bonds for CCC facilities, a portion of CCC teacher retirement costs, and Chancellor’s Office operations. Altogether, these Proposition 98 and non‑Proposition 98 funds comprise about two‑thirds of CCC funding. The remaining one‑third of funding comes primarily from student enrollment fees, other student fees (such as nonresident tuition, parking fees, and health services fees), and various local sources, including community service programs and facility rentals.

Figure 1

California Community Colleges Funding by Source

(Dollars in Millions Except Funding Per Student)

|

2017‑18 Actual |

2018‑19 Revised |

2019‑20 Proposed |

Change From 2018‑19 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Proposition 98 |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$5,757 |

$6,055 |

$6,117 |

$62 |

1.0% |

|

Local property tax |

2,963 |

3,119 |

3,321 |

202 |

6.5 |

|

Subtotals |

($8,720) |

($9,174) |

($9,438) |

($264) |

(2.9%) |

|

Other State |

|||||

|

Other General Funda |

$466 |

$819 |

$683 |

‑$136 |

‑16.6% |

|

Lottery |

231 |

253 |

253 |

—b |

‑0.1 |

|

Special funds |

96 |

95 |

93 |

‑2 |

‑2.2 |

|

Subtotals |

($793) |

($1,167) |

($1,028) |

(‑$138) |

(‑11.9%) |

|

Other Local |

|||||

|

Enrollment fees |

$457 |

$457 |

$459 |

$2 |

0.4% |

|

Other local revenuesc |

4,644 |

4,663 |

4,685 |

22 |

0.5 |

|

Subtotals |

($5,102) |

($5,120) |

($5,145) |

($24) |

(0.5%) |

|

Federal |

$288 |

$288 |

$288 |

— |

— |

|

Totals |

$14,903 |

$15,749 |

$15,899 |

$150 |

1.0% |

|

Full‑Time Equivalent (FTE) Students |

1,125,224 |

1,132,757 |

1,136,214 |

3,457 |

0.3% |

|

Proposition 98 Funding Per FTE Student |

$7,749 |

$8,099 |

$8,306 |

$207 |

2.6% |

|

Total Funding Per FTE Student |

$13,244 |

$13,903 |

$13,993 |

$89 |

0.6% |

|

aIn 2018‑19 and 2019‑20, includes the Governor’s proposal to provide supplemental payments to the California State Teachers’ Retirement System. bProjected to decline by $211,000. cPrimarily consists of revenue from student fees (other than enrollment fees), sales and services, and grants and contracts, as well as local debt‑service payments. |

|||||

Proposition 98 Funding Grows to $9.4 Billion Under Governor’s Budget. As Figure 2 shows, the Governor has several policy proposals that together account for $290 million in new Proposition 98 spending. These augmentations are partly offset by expiring one‑time funds. Under the Governor’s budget, Proposition 98 funding per full‑time equivalent (FTE) student rises to $8,306 in 2019‑20, an increase of $207 (2.6 percent) from the prior year. The Governor proposes no change to the CCC enrollment fee—leaving it at $46 per unit (or $1,380 for a full‑time student taking 30 semester units per year). The state last raised the CCC enrollment fee in July 2012.

Figure 2

2019‑20 Changes in CCC Proposition 98 Spending

(In Millions)

|

2018‑19 Revised Spending |

$9,174 |

|

Technical Adjustments |

|

|

Prior‑year one‑time spending |

‑$110 |

|

Other |

83 |

|

Subtotal |

(‑$26) |

|

Policy Proposals |

|

|

COLA for apportionments (3.46 percent) |

$248 |

|

College Promise fee waivers (extend program to sophomores) |

40 |

|

COLA for select student support programs (3.46 percent)a |

32 |

|

Enrollment growth (0.55 percent) |

26 |

|

Student Success Completion Grants (caseload adjustment) |

11 |

|

Legal services for undocumented students |

10 |

|

Strong Workforce Program (portion of costs shifted to one‑time funds) |

‑77 |

|

Subtotal |

($290) |

|

Total Changes |

$264 |

|

2019‑20 Proposed Spending |

$9,438 |

|

aApplies to Adult Education, Apprenticeship Programs, Extended Opportunity Programs and Services, mandates block grant, Disabled Students Programs and Services, CalWORKs student services, and campus child care support. COLA = cost‑of‑living adjustment. |

|

Apportionments

Below, we provide background on community college apportionment funding, describe the Governor’s major apportionment proposals, analyze those proposals, and offer associated recommendations.

Background

State Adopted New Credit Apportionment Funding Formula in 2018‑19. Prior to 2018‑19, the state based general purpose apportionment funding for both credit and noncredit instruction almost entirely on FTE enrollment. Last year, the state changed the credit‑based apportionment formula to include three main components, described in the next three paragraphs. For each of the three components, the state set new per‑student funding rates. In future years, these underlying rates are to receive a cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA). The new formula does not apply to credit enrollment generated from incarcerated students or high school students. It also does not apply to noncredit enrollment. Apportionments for these students remain based entirely on enrollment.

Base Allocation. As with the prior apportionment formula, the base allocation gives each district certain amounts for each of its colleges and state‑approved centers. It also gives each district funding for each credit FTE student ($3,727 in 2018‑19). Calculating a district’s FTE student count involves several somewhat complicated steps, but basically a district is funded based on a three‑year rolling average of its FTE student count. The rolling average takes into account a district’s current‑year FTE count and counts for the prior two years. As discussed later, enrollment growth for the budget year is funded separately.

Supplemental Allocation. The formula provides an additional $919 for every student who receives a Pell Grant, receives a need‑based fee waiver, or is undocumented and qualifies for resident tuition. Student counts are “duplicated,” such that districts receive twice as much supplemental funding ($1,838) for a student who is included in two of these categories (for example, receiving both a Pell Grant and a need‑based fee waiver). The allocation is based on student counts from the prior year.

Student Success Allocation. As Figure 3 shows, the formula also provides additional funding for each student achieving specified outcomes—obtaining various degrees and certificates, completing transfer‑level math and English within the student’s first year, and obtaining a regional living wage within a year of completing community college. Districts receive higher funding rates for the outcomes of students who receive a Pell Grant or need‑based fee waiver, with somewhat greater rates for the outcomes of Pell Grant recipients. As with the supplemental allocation, funding is based on outcome data from the prior year.

Figure 3

Student Success Allocation in New CCC Formula

2018‑19 Amounts by Student Outcome Measure and Student Type

|

Outcome Measure |

All Students |

Additional Funding for Each: |

|

|

Pell Grant Recipient |

Need‑Based Fee Waiver Recipient |

||

|

Associate degree for transfer |

$1,760 |

$666 |

$444 |

|

Associate degree |

1,320 |

500 |

333 |

|

Credit certificate requiring 18 or more units |

880 |

333 |

222 |

|

Transfer‑level math and English courses completed within first academic year |

880 |

333 |

222 |

|

Transfer to a four‑year university |

660 |

250 |

167 |

|

Nine or more career technical education units completed |

440 |

167 |

111 |

|

Regional living wage obtained within one year of community college completion |

440 |

167 |

111 |

Over Next Two Years, Base Allocation to Decrease, Student Success Allocation to Increase. In 2018‑19, roughly 70 percent of the cost of the formula stems from the base allocation, 20 percent from the supplemental allocation, and 10 percent from the student success allocation. The share for the base allocation is scheduled to decrease to roughly 65 percent in 2019‑20 and 60 percent in 2020‑21, whereas the share for the student success allocation is set to increase to 15 percent in 2019‑20 and 20 percent in 2020‑21. To achieve these changes in shares, statute specifies changes to the base and student success rates for each of the next two years. Whereas the base rate is set to decrease from $3,727 to $3,046 over the period, the student success rates are set to double.

New Formula Insulates Districts From Funding Losses During Transition. The new formula includes several hold harmless provisions for community college districts that would have received more funding under the former apportionment formula than the new formula. For 2018‑19, 2019‑20, and 2020‑21, these community college districts are to receive their total apportionment in 2017‑18, adjusted for COLA each year of the period. Beginning in 2020‑21, districts are to receive no less than the per‑student rate they generated in 2017‑18 under the former apportionment formula multiplied by their current FTE student count. To help districts with declining enrollment, the state also retained its longstanding one‑year hold harmless provision that allows districts to receive the greater of their calculated current‑ or prior‑year allotments.

State Allocates Enrollment Growth Separately From Other Components of the Apportionment Formula. Enrollment growth funding is provided on top of the funding derived from all the other components of the apportionment formula. Statute does not specify how the state is to go about determining how much growth funding to provide. Historically, the state considers several factors, including changes in the adult population, the unemployment rate, and prior‑year enrollment. When the state funds growth, the Chancellor’s Office uses a statutory formula to allocate that funding across community college districts. The allocation formula takes into account local educational attainment, unemployment, and poverty rates, as well as recent local enrollment trends. The formula is designed to direct a larger share of enrollment growth to high‑need districts.

Community College Districts Required to Conduct Annual Financial Audits. Districts must contract annually with a certified public accountant to conduct an audit that reviews their financial statements and verifies compliance with state and federal programs. The compliance portion of the audit includes a review of districts’ documentation relating to FTE enrollment. The Chancellor’s Office annually publishes an audit manual that provides guidelines for the documentation that must be collected and reviewed in assessing compliance.

Governor’s Proposals

Projects Higher Cost of 2018‑19 Apportionments but Does Not Cover Shortfall at This Time. The administration estimates that 2018‑19 apportionments cost $69 million more than provided for in the Governor’s current budget package. The higher cost is primarily a result of the student success allocation exceeding levels assumed in the 2018‑19 Budget Act. The administration indicates it will decide whether to provide additional funding to address the apportionment shortfall in May, at which time the state will have updated estimates of both apportionment costs and General Fund revenues.

Funds COLA and Enrollment Growth. The Governor’s budget includes $248 million to cover a 3.46 percent COLA for apportionments. In addition, the budget includes $26 million to cover 0.55 percent enrollment growth (equating to about 6,000 additional FTE students).

Postpones Scheduled Changes in Funding Formula Rates. The administration proposes to postpone for one year the scheduled changes in the share of apportionment funding linked with the base allocation and the student success allocation. Under the Governor’s proposal, the 2019‑20 funding formula rates would be the same as in 2018‑19, adjusted for COLA. The administration indicates the proposal is intended to provide additional time for the Chancellor’s Office to assess the reliability and quality of the student outcome data used in determining districts’ funding allocations. In 2020‑21, rates would change as currently scheduled, with base rates decreasing and student success rates doubling.

Caps Year‑to‑Year Growth in Student Success Allocation. The Governor also proposes to limit growth in a district’s student success allocation such that it can increase no more than 10 percent each year. This proposal helps to constrain the total costs of the formula and limits the fiscal effects of student outcome data that is of potentially poor quality.

Assessment

A Few Key Considerations in Deciding Whether to Cover Apportionment Shortfall. On the one hand, the Legislature could cover the shortfall, thereby signaling support for the new funding formula, with its emphasis on improving community college student outcomes. On the other hand, the Legislature could choose not to the cover the shortfall. Were the shortfall not to be covered, current practice would result in each district having its apportionment amount prorated downward. Based on the current estimated shortfall, district apportionments would be reduced by about 1 percent. Some of the 72 community college districts likely would be affected by the reduction more than others. For the 18 “hold harmless” districts—which expected to receive their 2017‑18 allotments adjusted by COLA—the shortfall would result in year‑over‑year growth slightly lower than COLA. These districts could be in a relatively difficult position if they increased employee salaries in 2018‑19 based on COLA. For the other 54 districts—which expected to grow at rates higher than COLA—the prorated reduction likely would be less difficult to accommodate, with their annual growth rates still relatively high. (For purposes of this comparison, we exclude the new online community college district created last year.)

Proposed Enrollment Growth Is in Line With Recent Systemwide Demand. The Governor proposes lower enrollment growth than the state has budgeted for CCC the past few years. The lower growth rate, however, is consistent with the growth districts have experienced the past few years. In 2016‑17, districts used $38 million of $114 million budgeted for enrollment growth. In 2017‑18, districts used $32 million out of $60 million budgeted for growth. For 2018‑19, the administration projects districts will use $33 million of the $60 million provided. Given these trends, we think the $26 million proposed by the Governor for 2019‑20 is reasonable.

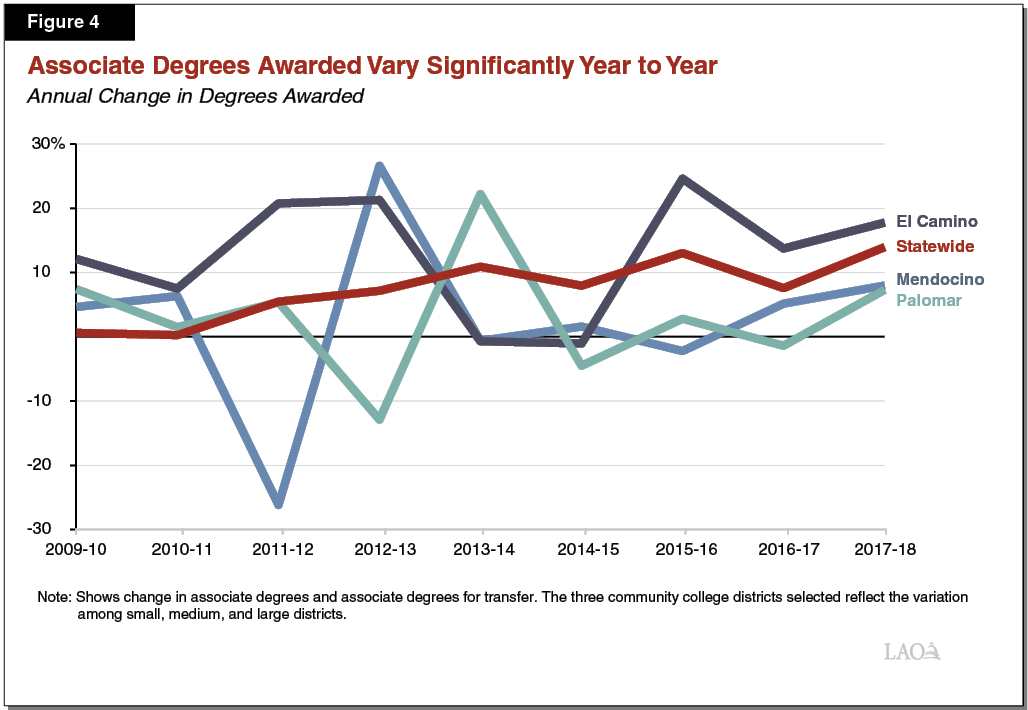

Student Outcome Data Can Fluctuate Year to Year. The administration has expressed concern with anomalies in the preliminary 2017‑18 student outcome data. For example, 2017‑18 statewide growth in the number of associate degrees awarded was the highest reported growth rate since 2008‑09. Our review of historical data, however, shows student outcome data to be prone to significant year‑to‑year variation (Figure 4). The variability is particularly large when looking at individual districts. Although the number of associate degrees awarded annually has increased statewide by an average of 7 percent per year since 2008‑09, almost all districts had at least one year where their awards declined from the previous year. During that same period, 59 districts had at least one year where the number of associate degrees awarded increased more than 20 percent. Similar variability also exists in historical data for certificates of greater than 18 units. Were these trends to continue, districts could see substantial year‑to‑year variation in their student success allocations.

Likely Several Causes of Data Variability. Because this data has not traditionally been audited or reviewed by external entities, the data may not be accurate or collected consistently. The degree counts for any particular year also could be affected by administrative decisions or delays in the actual processing or reporting of degrees. (Some students who complete their coursework in May, for example, might not receive their degree until July due to processing issues.) Data also could vary by year because of differences in student cohorts, with larger incoming cohorts producing a larger set of outcomes in subsequent years. Finally, some of the changes could be due to specific local circumstances. For example, a district might see an increase in its number of transfer students if a local CSU campus were to increase its transfer admissions rate that year.

Chancellor’s Office Plans to Add Auditing Guidelines for All Funding Formula Data. The 2018‑19 audit manual released by the Chancellor’s Office does not require auditors to review the data used to calculate the supplemental and student success allocations of the apportionments formula. The Chancellor’s Office indicates it will update auditing guidelines for 2019‑20 to include a review of this additional data. These new guidelines will provide the state with greater assurance that the data is being properly collected, tabulated, and reported.

Chancellor’s Office Plans to Conduct Review of Data Collection Processes This Spring. In addition to updating the audit manual, the Chancellor’s Office plans to hire an independent entity this spring to review the data collection and reporting processes of a random sample of districts. The goal of this review is to identify ways to improve the consistency and quality of data reported by districts. The review is expected to be completed by early May, such that its findings and recommendations could be incorporated into the final 2019‑20 budget.

Cap on Student Success Allocation Is a Crude Approach to Containing Formula Costs. In adopting the new funding formula, the Legislature tied a portion of funding to student outcomes to ensure districts had strong financial incentives to focus on student success. Capping the entire student success allocation is a crude approach that could work counter to this purpose. Most notably, the cap could reduce financial incentives for districts that are making genuine improvements in student outcomes.

Recommendations

Use a Three‑Year Rolling Average to Distribute Student Success Allocation. Given initial concerns with student outcome data, we recommend adopting the Governor’s proposal to postpone the scheduled changes in funding formula rates. Although postponing the changes and implementing new audit guidelines likely will help improve data quality and reliability, we are concerned that accurate and reliable data might still be prone to significant year‑to‑year volatility. To limit volatility in districts’ annual funding levels, we recommend the student success allocation be calculated using a three‑year rolling average of student outcome data. This approach is similar to the approach used to smooth out enrollment funding in the base allocation. Using a rolling average would mitigate the fluctuations that might occur because of data irregularities while still creating incentives for districts to improve outcomes over the long run.

Consider Ways to Promote Genuine Improvements Instead of Capping Student Success Allocation. Rather than implementing a cap on all outcomes‑based funding, we recommend the Legislature explore other cost‑containment options that continue to provide strong incentives for districts to make genuine improvements in student outcomes. For example, the Legislature could limit the amount of outcomes‑based funding generated by an individual student to the highest award earned in any particular year. Under such an approach, a student who earns an associate degree and a certificate would only generate outcomes‑based funding for the associate degree. This would prevent districts from generating additional funding by encouraging associate degree students to obtain unnecessary certificates, yet still reward districts that see improvement in student completion. Targeted modifications of this type would allow the state to reduce formula costs without reducing the incentive for districts to improve outcomes for students.

College Promise Program

Below, we (1) provide background on the Board of Governors (BOG) fee waiver program and the California College Promise program, (2) describe the Governor’s proposal to increase funding for the College Promise program, (3) assess that proposal, and (4) make an associated recommendation.

Background

Longstanding Program Provides Fee Waivers for CCC Students With Financial Need. When the Legislature introduced a CCC enrollment fee in 1984, it created the BOG fee waiver program. This program waives enrollment fees—currently $46 per unit—for students who have some financial need. (Financial need is defined as the difference between the total cost of attendance and the amount a student’s family can contribute toward that cost, as calculated by a federal formula.) Students apply for a fee waiver by completing either the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) or a shorter form developed by the Chancellor’s Office. Students may receive this fee waiver for any number of units taken. In 2017‑18, 41 percent of CCC students—representing almost two‑thirds of units taken—had their enrollment fees fully waived through this program.

State Recently Created New Program With Multiple Objectives. Chapter 735 of 2017 (AB 19, Santiago) created the California College Promise program. This program was inspired by tuition‑free college programs in other states (as explained in the box below), but it had broader goals beyond affordability. The Legislature’s stated intent in creating the program was to support CCC in increasing college readiness, improving student outcomes, and reducing achievement gaps. The state provided $46 million for the program in 2018‑19, the first year it was funded. Colleges are permitted—but not required—to use these funds to provide fee waivers to first‑time, full‑time students without financial need during their first year of college. To be eligible for these waivers, students must have no prior postsecondary coursework, enroll in 12 or more units per semester, and submit a FAFSA. Under the program, colleges also are permitted to use their College Promise funds for a broad range of other purposes, such as providing supplemental services to students.

College Promise Programs in National Context

In Other States, College Promise Programs Are Primarily Intended to Increase Affordability. California’s College Promise program was inspired by other states’ College Promise programs, which primarily focused on providing tuition‑free college. These other programs typically emerged in states that had not previously waived tuition for students with financial need. Accordingly, the programs are intended to reduce financial barriers to enrollment and simplify the messaging around affordability. Some programs are limited to full‑time students, with the intent of incentivizing students to take a higher course load that allows them to graduate more quickly.

In California, Existing Programs Already Addressed Affordability Goal. Before the California College Promise program, the BOG fee waiver program already waived enrollment fees for California Community Colleges (CCC) students with financial need, regardless of course load or prior academic experience. California also was already funding the Cal Grant program, which helps CCC recipients cover a portion of their living costs. In 2016‑17, the state began providing additional incentives for financially needy CCC students to enroll full time. Specifically, the Student Success Completion Grant provides full‑time CCC students receiving a Cal Grant with up to an additional $4,000 each year for living expenses. Because of these existing financial aid programs, California’s College Promise program is not as strictly focused on affordability as other states’ programs.

Statute Requires Colleges to Meet Six Requirements to Receive College Promise Funds. Figure 5 shows these requirements. The requirements are intended to incentivize colleges to adopt certain promising student support practices. In 2018‑19, 105 colleges have indicated they are meeting all six requirements and are, in turn, receiving College Promise funds. Nine colleges have opted out of the program, primarily out of concern that the sixth requirement—offering federal student loans—will increase their cohort default rates. (Colleges must maintain cohort default rates below a certain threshold to remain eligible for federal financial aid, including the Pell Grant program.)

Figure 5

Colleges Must Meet Six Requirements to Receive College Promise Funds

|

Participating Community Colleges Must: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Some Colleges Are Using Funds for Purposes Other Than Fee Waivers. The Chancellor’s Office allocates College Promise funds primarily based on the estimated number of students at each college who are eligible for fee waivers under this program. According to the Chancellor’s Office, 85 of the 105 colleges receiving College Promise funds are using some or all of their funds to provide fee waivers to first‑time, full‑time students without financial need. The remaining colleges are using the funds for other purposes. Examples of other uses include book stipends for financially needy students and additional financial aid staff positions. The Chancellor’s Office indicates that some colleges are opting to use College Promise funds for other purposes because they already had local programs waiving fees for students without financial need.

Governor’s Proposal

Governor Proposes $40 Million Ongoing for College Promise Expansion. The Governor proposes to augment funding for the program based on the estimated cost of waiving enrollment fees for first‑time, full‑time CCC students in their first two years of college who do not have financial need under the BOG fee waiver program. Under the Governor’s proposal, total ongoing funding for the program would be $80 million. (Though the 2018‑19 Budget Act included $46 million for the College Promise program, the administration now estimates that first‑year fee waivers cost only $40 million—the same as its estimated cost for second‑year fee waivers.) Consistent with the existing design of the program, colleges could use their additional College Promise funds to waive enrollment fees for qualifying students or for other purposes, such as student support services. The proposal does not change the six requirements colleges must meet to receive funds under this program.

Assessment

Outcomes From First Year of Program Are Not Yet Known. The state first funded the College Promise program in 2018‑19. As of this writing, current‑year data from the colleges is not available. This means the state does not yet know the effect of the program on overall enrollment, full‑time enrollment, financial aid participation, and other student outcomes. Without this information, the Legislature may consider it premature to expand the program.

Proposal Likely to Primarily Benefit Students Without Financial Need. Although the Chancellor’s Office does not know exactly how much colleges spent on College Promise fee waivers, it reports that 85 of the 105 participating colleges are using some or all of their allocation for fee waivers. We anticipate that many colleges would use the proposed augmentation for the same purpose. Because the students qualifying for fee waivers under this program are not considered financially needy, the Legislature may have higher priorities for these funds. Were the Legislature to reject the Governor’s proposal, CCC students with financial need would continue to have their second‑year enrollment fees covered by the BOG fee waiver program.

Colleges Have Other Stronger Fiscal Incentives to Improve Student Support. The College Promise program was designed to create a financial incentive for colleges to adopt six student support practices. Since creating the program, the Legislature has adopted other reforms that provide more explicit requirements and stronger financial incentives for colleges to improve student support. Chapter 745 of 2017 (AB 705, Irwin) requires colleges to use multiple measures to determine whether incoming students can be placed into transfer‑level coursework—one of the six practices required under the College Promise program. The Student Equity and Achievement Program, a $475 million block grant created in 2018‑19, requires colleges to adopt practices that overlap with two of the College Promise program requirements. The 2018‑19 budget package also created a new funding formula that bases a portion (roughly $800 million in the current year) of a college’s general purpose apportionments on student outcomes. Together, these recent reforms create incentives that are similar to—and considerably larger than—those created under the College Promise program.

Recommendation

Reject Governor’s Proposal to Increase Funding for College Promise Program. Because (1) it is too soon for the Legislature to evaluate the current College Promise program, (2) the program primarily benefits students without financial need, and (3) colleges now have stronger incentives to provide student support and improve student outcomes, we recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposed $40 million augmentation. Rejecting the proposal would free up a like amount of funding for other Proposition 98 priorities.

Facilities

In this section, we provide background on CCC facilities, describe the Governor’s proposal to authorize 12 new community college projects, assess the Governor’s proposal, and offer associated recommendations.

Background

State Funds Community College Facilities Through General Obligation Bonds. The state typically issues general obligation bonds to cover a portion of the cost of community college facility projects. A majority of voters must approve these bonds. From 1998 through 2006, voters approved four facility bonds that provided a total of $4 billion for community college facilities. Virtually no funding remains from these facility bonds.

New State Bond Approved in 2016. After a ten‑year gap, voters approved Proposition 51 in November 2016. The measure authorizes the state to sell $2 billion in general obligation bonds for community college projects. The funds may be used for an array of CCC projects, including buying land, constructing new buildings, modernizing existing buildings, and purchasing equipment.

Community College Districts Raise Local Funding for Facilities. The bulk of community college facility costs are covered with local funds. Districts typically sell local general obligation bonds to raise this support. Districts currently must get at least 55 percent of their voters to approve the sale of these local bonds. Since 1998 (when the voting threshold for local facility bonds was reduced from two‑thirds), community college districts have sold $26 billion in local general obligation bonds for facility projects.

Community College Facility Projects Ranked by Chancellor’s Office and Reviewed by the State. To receive state bond funding, community college districts must submit project proposals to the Chancellor’s Office. The Chancellor’s Office ranks all submitted facility projects using prioritization criteria adopted by the Board of Governors. Projects are prioritized in the following order:

- Life safety projects, projects to address seismic deficiencies or risks, and infrastructure projects (such as utility systems) at risk of failure.

- Projects to increase instructional capacity.

- Projects to modernize instructional space.

- Projects to complete campus build‑outs.

- Projects that house institutional support services.

Within these categories, projects with a local contribution receive greater consideration. After ranking the projects, the Chancellor’s Office submits capital outlay project proposals to the Legislature and Governor in the fall. The projects are reviewed as part of the annual state budget process.

Review Process Works Somewhat Differently for Life Safety Projects. To be approved in the highest‑priority category under the Chancellor’s Office process, a district must (1) have a third party entity identify the facility as an imminent danger to the occupants and (2) submit a project scope that is the least costly option for permanently addressing the problem. A project to address immediate electrical safety issues, for example, could not include renovations related to other building issues.

Almost Two Dozen Proposition 51 Projects Already Approved, Many More Recommended by Chancellor’s Office. To date, the state has approved 21 Proposition 51‑funded community college projects. The total state cost for all phases of these projects is estimated to be $587 million. For 2019‑20, the Chancellor’s Office is recommending 39 additional projects. Of the 39 projects, 6 projects were proposed last year but not funded. The remaining 34 projects were newly approved by the Chancellor’s Office in fall 2018. Of the projects, the Chancellor’s Office ranked 3 in the highest‑priority category, 15 in the second highest‑priority category, 15 in the third category, and 6 in the fourth category. The projects are estimated to have total state costs of $689 million.

Governor’s Proposals

Governor Proposes Funding 12 New CCC Projects for 2019‑20. The administration proposes to fund 12 of the 39 projects submitted by the Chancellor’s Office. As Figure 6 shows, the Governor’s budget includes $18 million in Proposition 51 funds for these projects. The funding would cover the cost of preliminary plans and working drawings. Total state costs for all phases of the projects, including construction, are estimated to be $254 million. Of the 12 projects, 1 is in the Chancellor’s Office’s highest‑priority category, 3 are in the second priority category, 5 are in the third priority category, and 3 are in the fourth category. The administration indicates it funded all projects that address life safety issues and include substantial local matches. (For two projects with little or no local match, the administration indicates it included the projects because the districts demonstrated financial hardship.)

Figure 6

Governor Proposes to Fund 12 New CCC Capital Outlay Projects

(In Thousands)

|

College |

Project |

2019‑20 State Cost |

All Years |

|

|

State Cost |

Total Costa |

|||

|

San Bernardino |

Technology replacement building |

$2,313 |

$34,411 |

$75,647 |

|

Redwoods |

Physical education replacement building |

5,379 |

60,648 |

60,648 |

|

American River |

Technology replacement building |

1,258 |

29,959 |

57,966 |

|

Saddleback |

New Gateway Building |

1,719 |

26,080 |

52,338 |

|

Alameda |

Auto and diesel technologies replacement building |

1,278 |

17,044 |

33,650 |

|

Los Angeles City |

Theater arts replacement building |

1,112 |

15,140 |

30,095 |

|

Merced |

New agricultural science and industrial technologies complex |

431 |

12,974 |

25,629 |

|

Santa Monica |

Art replacement complex |

793 |

10,901 |

21,526 |

|

Rio Hondo |

Music/Wray theater renovation |

847 |

9,873 |

20,486 |

|

Sequoias |

Basic skills replacement center |

1,365 |

15,635 |

17,350 |

|

Fresno |

Child development replacement center |

1,036 |

13,520 |

16,850 |

|

Butte |

Technology building renovation |

518 |

8,088 |

10,722 |

|

Totals |

$18,049 |

$254,273 |

$422,907 |

|

|

aCommunity college districts typically issue local general obligation bonds to pay for a share of project costs. |

||||

Governor Supports Next Phase of 15 Previously Approved Projects. The Governor’s budget also includes $341 million in Proposition 51 funds for the construction phase of 15 projects that were initially approved in 2017‑18 or 2018‑19 (Figure 7).

Figure 7

State Would Support 15 Continuing CCC Capital Outlay Projects

(In Thousands)

|

College |

Project |

2019‑20 State Cost |

All Years |

|

|

State Cost |

Total Costa |

|||

|

Santa Monica |

Science and mathematics building addition |

$37,031 |

$39,615 |

$78,102 |

|

Laney |

Learning resource replacement center |

22,812 |

24,417 |

75,686 |

|

Mount San Antonio |

New physical education complex |

53,993 |

57,541 |

72,238 |

|

Santa Rosa |

Science and mathematics replacement building |

30,882 |

33,076 |

65,589 |

|

Orange Coast |

Language arts and social sciences replacement building |

28,305 |

30,353 |

59,803 |

|

Allan Hancock |

Fine arts replacement complex |

22,873 |

24,526 |

48,318 |

|

Golden West |

Language arts replacement complex |

21,925 |

23,540 |

46,478 |

|

West Hills (North District Center) |

New library and instructional facility |

40,275 |

42,403 |

43,285 |

|

Santa Ana |

Russell Hall replacement |

19,192 |

20,729 |

40,948 |

|

Solano |

Library replacement building |

17,396 |

20,148 |

39,739 |

|

Compton |

Instructional replacement building |

14,891 |

16,167 |

24,995 |

|

Mission |

Portables replacement |

10,073 |

10,814 |

21,500 |

|

Merritt |

New child development center |

5,692 |

6,128 |

20,013 |

|

Imperial |

Academic buildings renovation |

8,647 |

9,043 |

17,741 |

|

Long Beach (Pacific Coast Campus) |

Construction trades building renovation, phase 1 |

6,712 |

7,304 |

13,107 |

|

Totals |

$340,699 |

$365,804 |

$667,542 |

|

|

aCommunity college districts typically issue local general obligation bonds to pay for a share of project costs. |

||||

Governor Postpones Additional Funding for Five Previously Approved Projects. For five projects that previously received funding for preliminary plans and working drawings, the administration proposes postponing construction funding. Figure 8 lists these projects, the year they were initially approved, and their estimated construction cost. Most of these projects have encountered delays with earlier project phases and, in three cases, the administration is concerned districts still are contributing little or no local match toward the project.

Figure 8

Five Previously Approved Projects Not Receiving Construction Funding in 2019‑20

(In Thousands)

|

College |

Project |

Year Initially Approved |

Estimated Construction Cost |

|

|

State |

Total |

|||

|

San Francisco (Ocean Campus) |

Utility infrastructure replacementa |

2017‑18 |

$76,257 |

$76,257 |

|

Pasadena City |

Armen Sarafian building seismic replacementb |

2017‑18 |

53,458 |

55,523 |

|

Redwoods |

Arts building replacementc |

2018‑19 |

22,191 |

22,191 |

|

Fullerton |

Business 300 and Humanities 500 Renovationc |

2017‑18 |

15,714 |

30,115 |

|

San Francisco (Alemany Center) |

Seismic and code renovationsa |

2017‑18 |

14,398 |

14,398 |

|

aBoth project delays and insufficient local match. bInsufficient local match. cProject delays. For Redwoods project, district demonstrated financial hardship and no local match is expected. |

||||

Assessment

Governor Proposes More Projects Than in Previous Years. The Newsom administration shows a greater commitment to allocating Proposition 51 bond funding than the previous administration. Compared to the 12 projects Governor Newsom is proposing, the Brown administration proposed only five projects each of the past two years. Despite proposing more projects, the state still would be on a somewhat slow track to expend all Proposition 51 bond funds. Accounting for all phases of all projects to date (including the 12 proposed projects), the state would have committed $668 million of the $2 billion authorized by Proposition 51. (This amount excludes construction funding for the postponed projects.) At this pace, the state would be on track to exhaust Proposition 51 bond funding in about nine years (by 2025‑26). Given the amount of projects approved by the Chancellor’s Office, this somewhat slow pace is driven by state‑level decisions, not lack of demand from community colleges.

Different Approaches to Life Safety Issues Is Creating Confusion for Districts. Although the Chancellor’s Office has a specific process for addressing life safety issues, the administration has its own approach. The administration reviews every project approved by the Chancellor’s Office and prioritizes those that appear to be addressing life safety issues, even if life safety is not the primary reason for the project. In contrast, the Chancellor’s Office may deem a project higher priority because it addresses a lack of instructional capacity, even if no life safety issues are involved. Inconsistency in how the two agencies are reviewing projects is resulting in confusion for districts, as their projects are effectively being subjected to two competing standards.

Unclear if Prioritizing Life Safety Is the Right Approach for Community Colleges. The administration’s approach to prioritizing community college projects is consistent with the approach generally used for state‑owned buildings, where the state is directly responsible for safety. This approach, however, might not be the right approach within the context of community college facilities. Community college districts are the ones directly responsible for any life safety issues related to their facilities. Additionally, the administration’s approach can reward districts that have done a poor job maintaining their facilities. For example, if two districts submit requests to modernize buildings that are of the same age, the administration’s approach prioritizes the project that has a life safety issue. The life safety issue, however, could be the result of poor district maintenance practices. The Chancellor’s Office approach, which requires third‑party review and limits the scope of life safety projects, does not create these poor incentives to the same degree.

Recommendations

Consider Approving Additional CCC Projects. Given the somewhat slow pace of project approvals and our concerns with the administration’s rationale for which projects it has included in its budget, the Legislature may want to consider approving more projects than the Governor. In choosing which projects to fund, the Legislature could evaluate the projects based on the Chancellor’s Office priority categories or work with the Chancellor’s Office and administration to develop another set of clear, agreed‑upon criteria. Figure 9 lists the projects approved by the Chancellor’s Office but not funded in the Governor’s budget.

Figure 9

Projects Approved by Chancellor’s Office but Not Included in Governor’s Budget

(In Thousands)

|

College |

Project |

Priority Categorya |

2019‑20 State Costb |

All Years |

||

|

State Cost |

Total Cost |

|||||

|

Folsom Lake |

Instructional buildings phase 2 |

2 |

$1,280 |

$31,374 |

$58,488 |

|

|

Mount San Jacinto |

Math and Sciences building |

2 |

1,560 |

26,816 |

50,673 |

|

|

Clovis |

Applied Technology building |

2 |

1,794 |

26,091 |

49,893 |

|

|

Irvine Valley |

Fine arts building |

2 |

1,624 |

23,202 |

45,072 |

|

|

Long Beach City |

Music/theatre complex |

2 |

1,681 |

23,212 |

44,606 |

|

|

Mount San Jacinto |

Science and Technology building |

2 |

1,854 |

23,203 |

44,071 |

|

|

Santa Barbara City |

Physical education replacement |

1 |

3,189 |

41,103 |

41,928 |

|

|

West Valley |

Learning resource center renovation |

3 |

1,623 |

19,993 |

40,132 |

|

|

Los Rios (Natomas Education Center) |

Natomas Center phases 2 and 3 |

2 |

886 |

27,805 |

39,386 |

|

|

Woodland |

Performing arts facility |

4 |

1,427 |

19,426 |

37,659 |

|

|

West Hills Lemoore |

Instructional Center phase 1 |

2 |

1,634 |

23,413 |

31,726 |

|

|

Kern (Delano Center) |

LRC multipurpose building |

2 |

1,191 |

16,106 |

31,242 |

|

|

Skyline |

Workforce development center |

3 |

860 |

14,621 |

28,750 |

|

|

Laney |

Theater buildings renovation |

3 |

709 |

8,213 |

26,454 |

|

|

Chaffey |

Instructional Building 1 |

2 |

951 |

12,990 |

26,132 |

|

|

Cerritos |

Health Sciences Building 26 renovation |

3 |

1,054 |

12,665 |

24,712 |

|

|

Merritt |

Horticulture building replacement |

3 |

755 |

10,065 |

24,506 |

|

|

Cañada |

Instructional center renovation |

3 |

676 |

8,253 |

23,682 |

|

|

Lake Tahoe |

RFE and Science renovation |

3 |

1,447 |

11,056 |

21,564 |

|

|

Porterville |

Allied health building |

2 |

835 |

10,919 |

20,827 |

|

|

Monterey Peninsula |

Public safety center phase 1 |

4 |

714 |

9,223 |

19,058 |

|

|

Los Rios (Elk Grove Center) |

Elk Grove Center phase 2 |

2 |

410 |

8,946 |

17,013 |

|

|

Reedley |

New child development center |

4 |

818 |

10,388 |

14,366 |

|

|

Canyons |

Boykin Hall renovation |

3 |

334 |

4,057 |

7,755 |

|

|

Cabrillo |

Buildings 500, 600 and 1600 renovation |

3 |

252 |

3,622 |

7,268 |

|

|

Monterey Peninsula |

Music facilities phase 1 renovation |

3 |

222 |

2,454 |

6,347 |

|

|

San Mateo |

Water supply tank replacement |

1 |

505 |

5,669 |

6,298 |

|

|

Totals |

$30,285 |

$434,885 |

$789,608 |

|||

|

aReflect’s Chancellor’s Office priority categories. bReflects cost of preliminary plans and working drawings. |

||||||

Explore Better Ways to Address Life Safety Concerns. We recommend directing the administration and the Chancellor’s Office to develop one agreed‑upon framework for how life safety issues should be considered in the review of community college projects. If the administration and Chancellor’s Office cannot come to an agreement, we recommend the Legislature codify an approach in statute. We believe the framework should ensure state funding is available in case of a facility emergency but also have strong incentives for districts to maintain their facilities in good condition. Additionally, we think the framework should ensure districts provide a local contribution based on their local resources. Creating one set of rules will simplify the process, clarify expectations for districts, and help the state more thoughtfully prioritize among projects.

California State University

In this section, we provide an overview of CSU’s budget, then assess the Governor’s proposals to fund (1) compensation and other operational cost increases, (2) enrollment growth, (3) the Graduation Initiative, (4) Project Rebound, and (5) a set of facility projects. We conclude by discussing options for how the Legislature might cover the costs associated with these budget priorities or other priorities it identifies.

Overview

Below, we provide an overview of the Governor’s proposed budget for CSU, highlighting how CSU’s core and noncore funding levels would change.

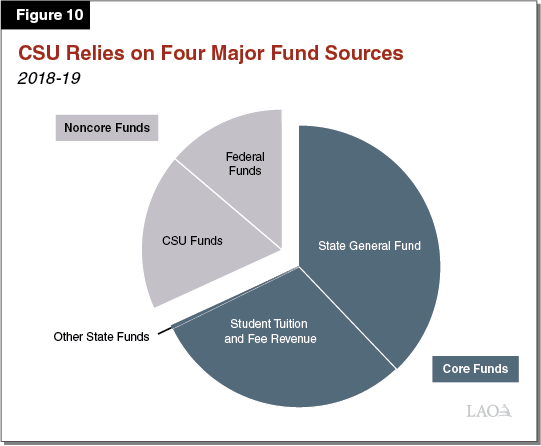

CSU Receives Its Funding From Four Main Sources. In 2018‑19, CSU is receiving a total of $10.9 billion in funding from all sources. As Figure 10 shows, about two‑thirds ($7.4 billion) comes from core funds—a combination of state General Fund, student tuition and fees, and other state funds (primarily lottery funds). The remaining one‑third ($3.5 billion) comes from federal funds and other CSU funds (which includes revenue from various campus enterprises such as parking facilities and student dormitories).

Under Governor’s Budget, CSU Funding Would Increase by a Total of $504 Million (4.6 Percent). Funding from all sources (core and noncore funds) would grow to $11.4 billion in 2019‑20. The Governor’s budget assumes that federal funds and other CSU funds are flat year over year, with all of the increase coming from core funds. Greater state General Fund support accounts for the bulk of the increase ($465 million, 11.3 percent). Student tuition and fee revenue would increase slightly ($39 million, 1.2 percent) due to proposed enrollment growth. In 2019‑20, General Fund and tuition support for CSU would be $4.6 billion and $3.3 billion, respectively.

Ongoing Core Funding Would Increase by $404 Million (5.6 Percent). Figure 11 looks at only ongoing core funding for CSU, removing noncore and one‑time funding. As with CSU’s overall budget, greater state General Fund support accounts for the bulk of the proposed increase in ongoing core funding. Year‑over‑year ongoing General Fund support would increase by $364 million (9.2 percent). Figure 12 shows the specific ongoing General Fund spending increases the Governor proposes. The Governor links his proposed funding increases with an expectation that CSU not increase tuition in 2019‑20. On a per‑student basis, ongoing core funding in 2019‑20 would increase by $661 (3.7 percent)—reaching $18,445.

Figure 11

Ongoing Core Funding for CSU Increases Under Governor’s Budget

(Dollars in Millions Except Funding Per Student)

|

2017‑18 Actual |

2018‑19 Revised |

2019‑20 Proposed |

Change From 2018‑19 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

State General Fund |

$3,713 |

$3,959 |

$4,324a |

$364 |

9.2% |

|

Tuition and Feesb |

3,275 |

3,251 |

3,290 |

39 |

1.2 |

|

Other State Fundsc |

57 |

44 |

44 |

— |

— |

|

Totals |

$7,046 |

$7,254 |

$7,657 |

$404 |

5.6% |

|

FTE studentsd |

410,060 |

407,867 |

415,133 |

7,266 |

1.8% |

|

Funding per student |

$17,182 |

$17,784 |

$18,445 |

$661 |

3.7% |

|

aIn addition, Governor’s budget includes $7 million ongoing General Fund to the Department of Social Services for provision of legal services to undocumented students and immigrants at CSU campuses. bIncludes funds that CSU uses to provide tuition discounts and waivers to certain students. In 2019‑20, CSU plans to provide $701 million in such aid. cIncludes lottery funds and $2 million ongoing from the State Transportation Fund for transportation research. dOne FTE represents 30 credit units for an undergraduate and 24 credit units for a graduate student. Includes resident and nonresident students. FTE = full‑time equivalent. |

|||||

Figure 12

Governor’s Budget Includes Six Ongoing

General Fund Increases for CSU

(In Millions)

|

Compensation and other operational costs |

$193.0 |

|

Enrollment growth (2 percent) |

62.0 |

|

Graduation Initiative |

45.0 |

|

Pension costs |

44.2 |

|

Retiree health benefit costs |

19.8 |

|

Project Rebound |

0.3 |

|

Total |

$364.2a |

|

aIn addition, the Governor’s budget proposes $7 million ongoing General Fund to the Department of Social Services for provision of legal services to undocumented students and immigrants at CSU campuses. |

|

Governor Proposes $264 Million in One‑Time Initiatives. The Governor’s budget package also contains three one‑time initiatives for CSU. The largest is $247 million for CSU to undertake additional deferred maintenance projects or expand its campus child care facilities. Building off certain budget actions last year, the Governor also proposes $15 million to further CSU’s partnerships with social services agencies to address student food and housing insecurity. In addition, the Governor proposes $2 million for the Chancellor’s Office to conduct a study of a potential new campus in Stockton.

Compensation and Other Operational Costs

Below, we provide background on CSU employee compensation and other operating costs, then describe the Governor’s associated proposals, assess those proposals, and identify issues for legislative consideration.

Background

Compensation Is the Largest Component of CSU’s Core Budget. Like other state agencies, salaries and benefits make up a significant share of CSU’s core budget (about 75 percent). Compensation almost always represents CSU’s largest cost pressure each year.

Most CSU Employees Are Represented by a Union. Currently, CSU has more than 50,000 permanent employees across 23 campuses and the Chancellor’s Office. About 90 percent of these employees (primarily consisting of faculty and support staff) are represented, while the remaining 10 percent of employees (primarily consisting of managers and supervisors) are nonrepresented. Throughout the year, CSU also employs more than 15,000 student assistants and other temporary staff. These groups are not part of a bargaining unit.

Board of Trustees, Not the Legislature, Approves CSU Collective Bargaining Agreements. The California Department of Human Resources typically represents the Governor in labor negotiations between the state and its employees. The resulting bargaining agreements must be ratified by the Legislature before going into effect and the state directly funds the associated cost of the agreements. In the case of CSU, state law gives the Board of Trustees authority to negotiate collective bargaining agreements. The Chancellor’s Office represents the Trustees during these negotiations and the resulting agreements must be ratified by the Trustees before going into effect. The Trustees are expected to manage the cost of these agreements within CSU’s overall budget. The Trustees also have delegated authority to the Chancellor and campus presidents to set salary levels for nonrepresented employees and any associated salary increases must be funded within CSU’s overall budget.

CSU Participates in CalPERS, Is Directly Responsible for a Share of Its Pension Costs. CalPERS administers pension benefits for CSU and most other state employees. Employer contributions to CalPERS are set by the CalPERS board. Historically, the state directly funded all of CSU’s employer costs in the annual budget. Several years ago, the state modified its approach to covering CSU pension costs. Under the new approach, CSU is to take into account pension costs when it makes new staffing and salary decisions. Any new pension costs incurred beyond the 2013‑14 payroll level are CSU’s direct responsibility.

No Clear Expectation on How CSU Is to Cover Its Share of Pension Costs. In 2015‑16 and 2016‑17, the state provided sufficient unrestricted funding to CSU for it to cover its direct pension costs. In the last two fiscal years, CSU’s unrestricted augmentation has not been sufficient to cover all of its bargaining agreements and direct pension costs. CSU indicates it covered its direct pension costs these past two years by redirecting funds from other activities.

CalPERS Also Administers CSU’s Health Plans. Every year, CalPERS negotiates with health care providers to establish the premiums for the plans offered to state employees, including CSU employees. Like other state employers, CSU’s contribution amount to employee health benefits is determined by identifying the four health plans with the highest enrollment of state employees and calculating a weighted average of the premiums for these plans. Statute sets a default contribution level whereby CSU pays 100 percent of the average premium cost for employees and 90 percent of the average additional premium costs for dependents (known as the “100/90” formula). Though the 100/90 formula is a default, statute permits CSU to collectively bargain a different formula for employees. (In practice, the 100/90 formula applies to nearly all CSU employees.) Each year when the average premium cost increases, CSU must cover the associated cost for its active employees. The state directly covers the associated cost for retired CSU employees.

Some CSU Workers Subject to State’s Minimum Wage Law. Like other employers, CSU is subject to California’s minimum wage law. According to the Chancellor’s Office, only student assistants and other temporary staff earn the minimum wage at CSU. All other CSU employees (represented and nonrepresented) currently earn more than minimum wage. Chapter 4 of 2016 (SB 3, Leno) increases the statewide minimum wage over a period of several years, reaching $15 per hour by January 2022.

Virtually All Represented Employees Currently Under Contract Through 2019‑20. The CSU system has 13 represented employee groups. The largest group is the California Faculty Association (CFA), which represents more than 25,000 CSU faculty, librarians, counselors, and coaches. In November 2017, the Trustees ratified a contract with CFA that provides a 3.5 percent general salary increase in November 2018, followed by a 2.5 percent increase in July 2019. In January 2017, the Trustees ratified an agreement with CSU’s second largest group (CSU Employees Union), which represents more than 15,000 employees across four bargaining units. Under the agreement, represented employees receive a 3 percent salary increase retroactive to 2017‑18 and 3 percent increases in both 2018‑19 and 2019‑20. Of the remaining eight bargaining units (which collectively represent less than one‑quarter of CSU employees), seven have approved contracts in place through the end of 2019‑20. CSU’s approximately 300‑member police association currently is the only bargaining unit with an open contract for 2019‑20.

Salary Costs for Represented and Nonrepresented Employees to Increase by $148 Million in 2019‑20. CSU’s contract obligations for salary increases totaled $122 million in 2018‑19. The state effectively covered this cost by providing an unrestricted base augmentation of a like amount in the 2018‑19 Budget Act. CSU estimates that these continuing bargaining agreements, coupled with a planned 3 percent salary increase for nonrepresented employees, will total $148 million in additional costs in 2019‑20.

CSU Has Identified Four Other Operational Cost Pressures. In addition to new salary costs in 2019‑20, CSU has identified three other ongoing compensation‑related cost increases:

- $26 million attributed to retirement costs above CSU’s 2013‑14 pensionable payroll level. (Of this amount, $14 million is associated with 2019‑20, $5 million with 2018‑19, and $7 million with 2017‑18. Though CSU redirected funds on a short‑term basis to cover the prior‑year amounts, it would like an ongoing increase to cover the costs moving forward.)

- $7.3 million resulting from a 1.3 percent increase in CalPERS‑negotiated employer health care premium costs.

- $6.8 million resulting from an increase in the state minimum wage from $11 to $12 per hour beginning January 2019.

In addition to these operational costs, CSU is scheduled to open about 400,000 square feet of new facility space in 2019‑20. Based on past analysis, CSU estimates the cost to fund the regular operation of these facilities (such as utilities, general upkeep, and basic repairs) is $11.75 per square foot. Based on this amount, CSU estimates that it will incur $4.7 million in costs associated with this new space in the budget year.

Governor’s Proposal

Proposes $193 Million Ongoing for Compensation and Other Operational Costs. According to the administration, this amount is intended to cover CSU’s $148 million in higher salary costs, as well as its four other identified operational cost pressures. (The amount includes the $12 million CSU requested to cover its direct pension cost increases in 2017‑18 and 2018‑19.)

Provides $64 Million Ongoing for Some Pension Costs and Retiree Health Care Costs. Due to higher CalPERS‑determined employer contribution rates for 2019‑20, the budget provides CSU a $44 million adjustment. This amount is based on CSU’s 2013‑14 payroll level, per current policy. In addition, the budget provides a $20 million adjustment to cover higher health benefit costs for CSU retirees. This adjustment is due to an anticipated increase in the number of retirees in the budget year as well as higher premium costs.

Assessment

Recent Bargaining Agreements Generally Have Been More Favorable to CSU Employees Than Other State Employees. Though collective bargaining agreements vary among state bargaining units and strict comparisons among the agreements are difficult, represented CSU employees generally have received better terms than their state employee counterparts the past few years. This is because most state agreements are now requiring employees to pay a larger share of their pension and retiree health care costs. In contrast, CSU agreements have not been requiring these higher employee contributions. As a result, the roughly 3 percent annual salary increases that have been granted the past few years to CSU and other state workers are stretching farther for CSU workers.

Legislature May Want to Revisit Approach to Funding CSU Staffing and Pension Costs. The policy that the state enacted in 2013‑14 is predicated on CSU being able to control any new staffing and salary decisions. One might hold this view given CSU is responsible for its bargaining agreements and the Legislature does not ratify them. Another perspective is that CSU has limited ability to control these costs given legislative expectations most years for CSU to grow enrollment, hire associated faculty, provide cost‑of‑living adjustments, and offer other salary enhancements. Going forward, the Legislature may want to revisit how prescriptive it wishes to be with CSU staffing decisions, including whether to fund all CSU pension costs directly or devolve full responsibility for these costs to CSU and its bargaining agreements.

Opportunity for Legislature to Signal Its Expectations on Future CSU Contracts. At a minimum, the Legislature has an opportunity to signal to the Chancellor’s Office what it thinks is reasonable to fund in bargaining contracts for 2020‑21. For example, the Legislature could signal its expectation that CSU salary increases be aligned with inflation. Prior to negotiations, the Legislature also could encourage the Chancellor’s Office to commission an analysis comparing CSU faculty and staff compensation levels with peer institutions. Such an analysis could include an examination of employee retention rates and the extent to which campuses report having sufficient candidate pools for open positions. Considerations such as these could assist CSU and the Legislature in negotiating and funding new agreements.

Enrollment Growth

Below, we provide background on the state’s eligibility policies and CSU enrollment levels, describe the Governor’s proposal to fund enrollment growth, and highlight factors for the Legislature to consider when deciding on an enrollment level for CSU in the budget year.

Background

Longstanding State Policies Determine Which Students Are Eligible to Attend CSU. Under the state’s 1960 Master Plan for Higher Education, community college students who complete their lower‑division work with a minimum 2.0 grade point average (GPA) are eligible to attend CSU as upper‑division undergraduate students. The Master Plan limits freshman admission to CSU to the top one‑third of high school graduates. To draw from the top 33 percent, CSU has historically structured its admission policies to require high school students to (1) complete a specified set of college‑preparatory coursework and (2) attain a certain mix of high school GPA and standardized aptitude test scores (historically SAT or ACT scores). Through periodic eligibility studies, CSU is able to determine if it is drawing its freshman admits from its Master Plan eligibility pool. If CSU is drawing from a smaller or larger pool, the state traditionally has expected CSU to adjust its admission requirements accordingly.

CSU Has Higher Admission Standards for Impacted Campuses and Programs. While CSU has minimum systemwide eligibility requirements for transfer and freshman applicants, some “impacted” campuses and programs (those with more student demand than available slots) adopt stricter admissions criteria. Currently, six campuses are fully impacted—having higher admissions criteria for all their programs. Most campuses have at least one impacted program, often nursing.

State Typically Sets Enrollment Growth Target and Funds Growth According to Per‑Student Formula. In most years, the Legislature provides funding in the annual budget act to support a specified level of enrollment growth at CSU. The total amount of funding provided each year is based on the number of additional students the Legislature wants CSU to enroll multiplied by a per‑student funding rate (derived by a “marginal cost” formula). The formula takes into account the additional faculty, support services, and other resources that are required to serve each additional student. The per‑student costs are shared by the state General Fund and student tuition revenue. In 2019‑20, CSU’s marginal cost is $11,322 per FTE student, with a state share of $8,499.

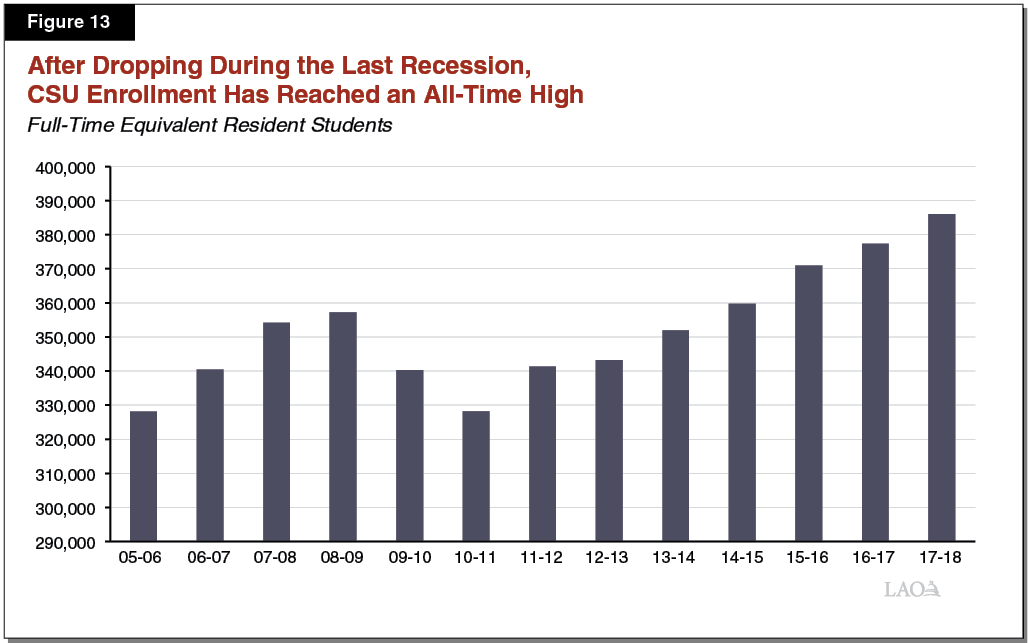

CSU Enrollment Is at an All‑Time High. Figure 13 shows that resident enrollment levels at CSU have increased each year since 2010‑11, growing at an average annual rate of about 2 percent over the period. In 2017‑18, CSU enrolled 386,000 FTE students, about 30,000 more than campuses were serving in 2008‑09 (its previous peak).

Legislature Provided CSU One‑Time Enrollment Growth Funding in 2018‑19. Typically, the Legislature provides ongoing funding for enrollment growth. In a departure from traditional practice, the 2018‑19 budget provided CSU with $120 million one time for enrollment growth. Provisional language permits CSU to spend these funds over a four‑year period to support a student cohort of 3,641 FTE students (1 percent over the 2017‑18 level). For 2018‑19, CSU has allocated $21.9 million of the $120 million to campuses (representing 2,677 FTE students). Campuses are using these funds for various purposes, including hiring temporary faculty to teach more course sections in spring 2019.

Governor’s Proposal

Provides $62 Million Ongoing for 2 Percent Enrollment Growth. This amount would fund about 7,300 resident FTE students in 2019‑20. The administration has indicated its intention that this funding be for resident undergraduate students. In addition, CSU plans to use about $30 million of the $120 million in one‑time funding the state provided in 2018‑19 for enrollment growth. CSU intends to support about 3,600 additional FTE students in 2019‑20 with these funds.

Assessment

Several Factors to Consider in Deciding Enrollment Growth. The Legislature has at least four key factors to consider when setting a CSU enrollment target, discussed below. Whereas most factors suggest enrollment growth funding may not be needed in the budget year, a few factors suggest that some level of enrollment growth may be justified.

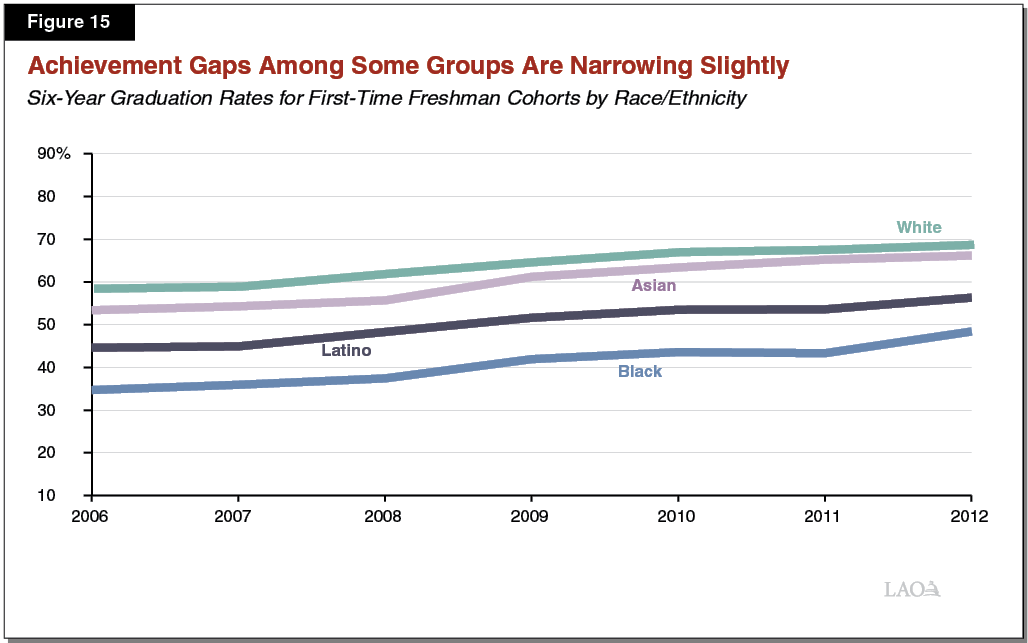

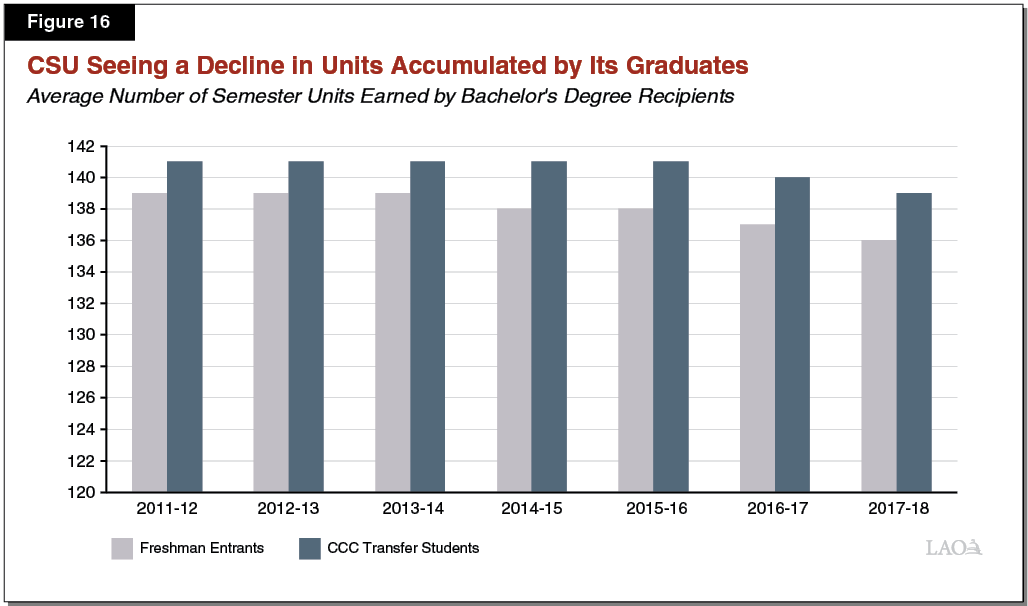

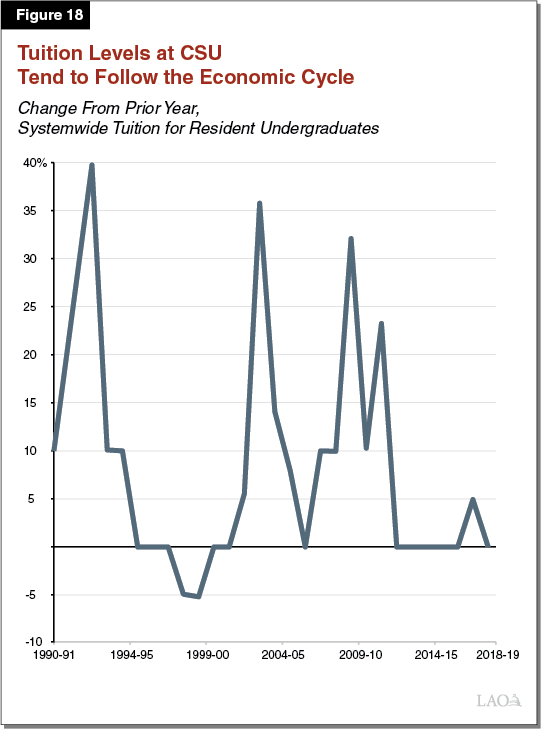

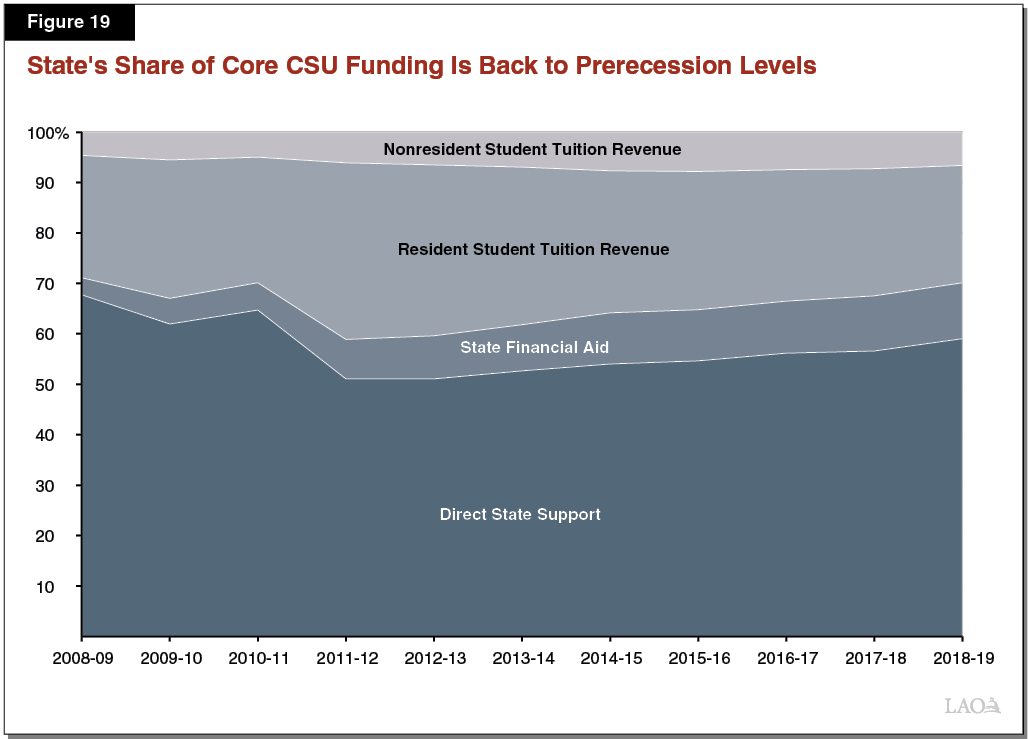

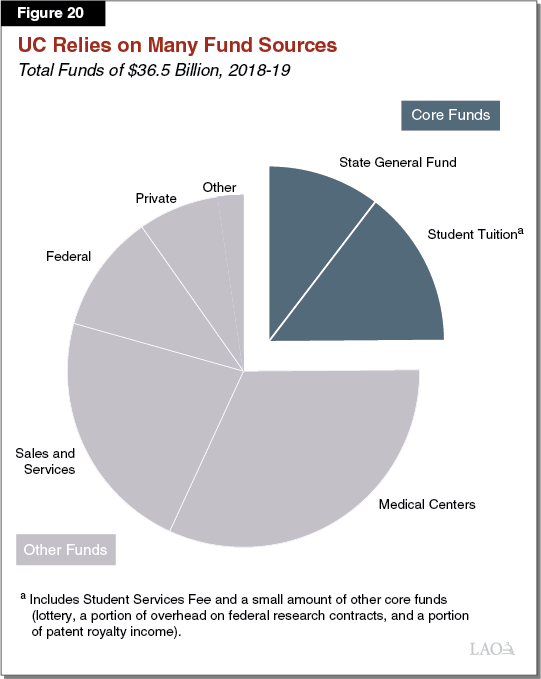

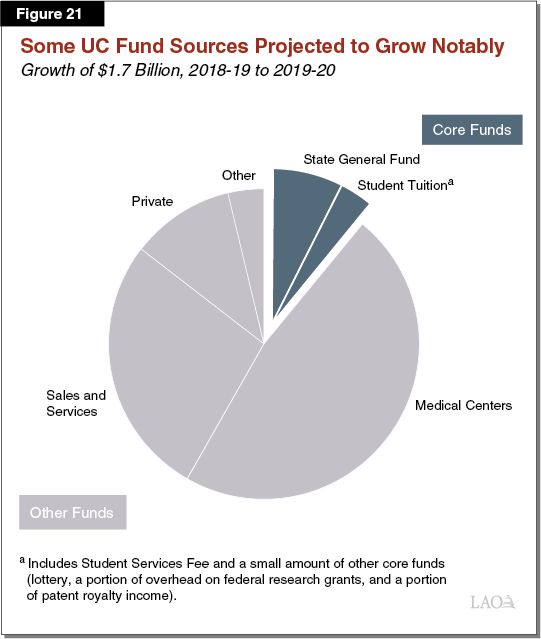

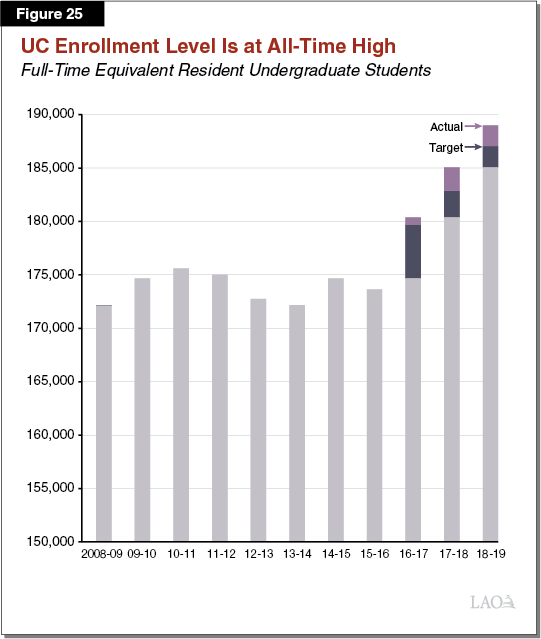

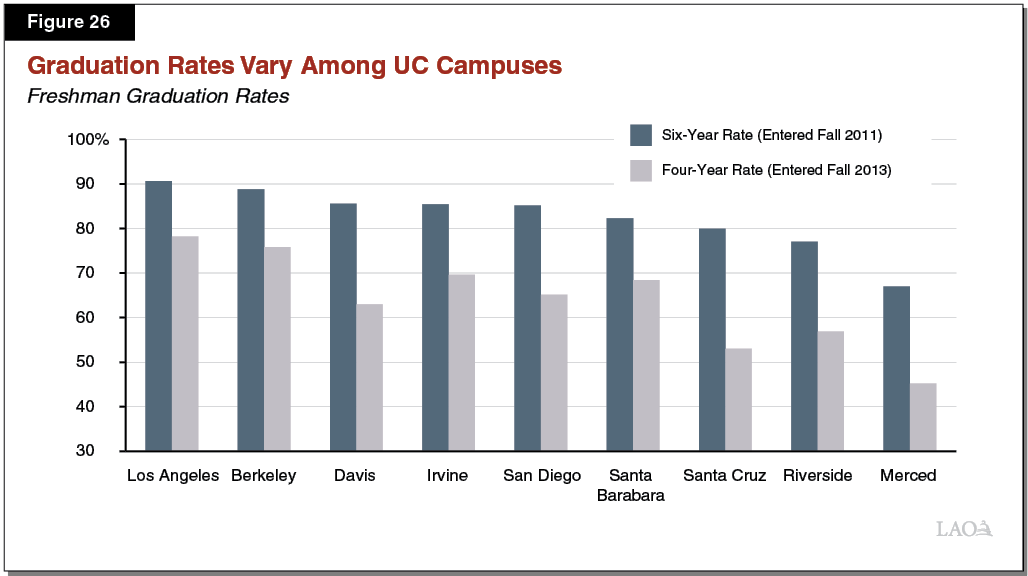

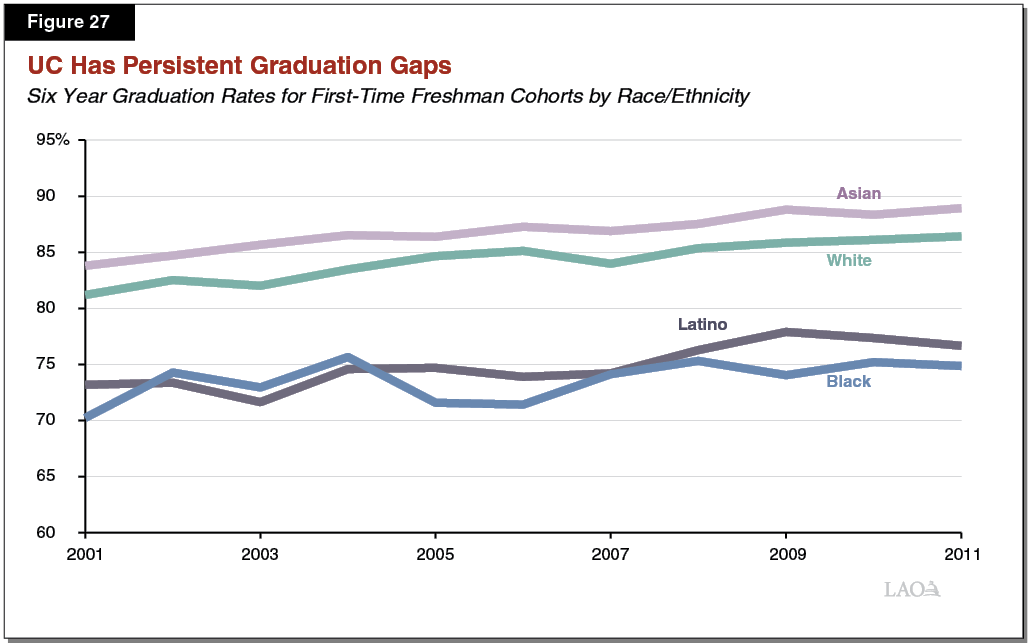

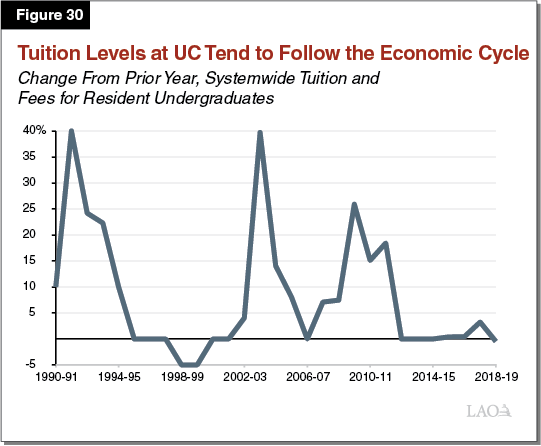

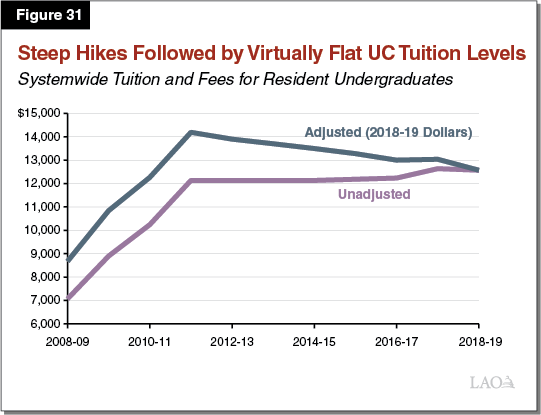

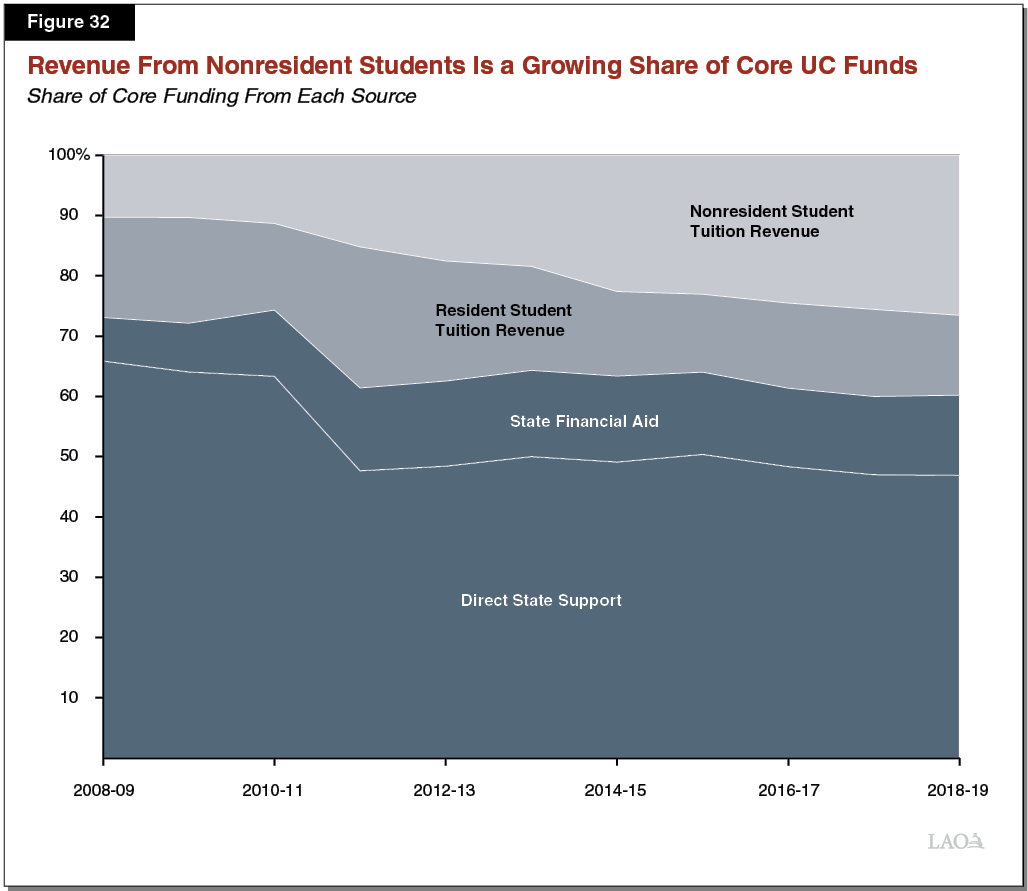

Demographic Projections Show Decline in High School Graduates. The number of high school graduates in the state is expected to decrease by 0.8 percent in 2018‑19. This means that, all other factors staying the same, enrollment demand for freshman slots in 2019‑20 would decrease accordingly. High school graduates in 2019‑20 also are projected to decrease (by 0.4 percent).