LAO Contacts

- Helen Kerstein

- High-Speed Rail

- Anita Lee

- Department of Motor Vehicles

- Shawn Martin

- California Highway Patrol

- Jessica Peters

- Caltrans

- Anthony Simbol

- Motor Vehicle Account

February 26, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

Transportation Proposals

- Overview of Governor’s Transportation Budget

- Motor Vehicle Account (MVA) Fund Condition

- Caltrans

- California Highway Patrol

- Department of Motor Vehicles

- High‑Speed Rail Authority

Executive Summary

Overview of Governor’s Transportation Budget

Total Proposed Spending of $23.5 Billion. The Governor’s budget provides a total of $23.5 billion from all fund sources for the state’s transportation departments and programs in 2019‑20. This is a net increase of $1.4 billion, or 6 percent, over estimated expenditures for the current year. Specifically, the budget includes $14.6 billion for the California Department of Transportation, $2.8 billion for local streets and roads, $2.8 billion for the California Highway Patrol (CHP), $1.2 billion for the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV), $1 billion for transit assistance, and $1.1 billion for various other transportation programs.

Motor Vehicle Account (MVA) Fund Condition

MVA Faced Operational Shortfalls in Recent Years. The MVA, which receives most of its revenues from vehicle registration and driver license fees, mainly supports the activities of CHP and DMV. Over the last several years, the MVA has periodically faced operational shortfalls—mainly due to increases in MVA expenditures. In the current year, the MVA faces an operational shortfall of almost $400 million and will need to draw down its fund balance that has accumulated in prior years. In recognition of the MVA’s estimated operational shortfalls, the Governor’s budget includes various proposals that are intended to benefit the MVA, such as shifting from “pay‑as‑you‑go” to financing for certain previously approved CHP field office replacement projects and shifting certain MVA expenditures to the General Fund.

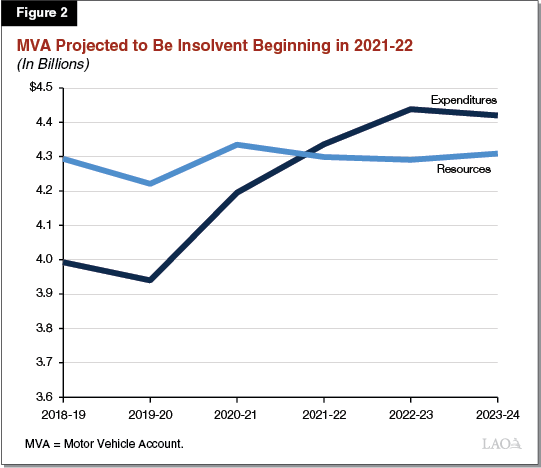

Governor’s Proposals Benefit MVA, but Projected Insolvency in 2021‑22. The Governor’s proposals, however, would not fully address the account’s structural imbalance. The administration’s five‑year projection (2019‑20 through 2023‑24)—which reflects expenditures already approved by the Legislature and those proposed in the Governor’s budget—estimates that the MVA’s fund balance will become insolvent in 2021‑22 with a shortfall of roughly $40 million that grows to roughly $150 million in 2022‑23. Given the projected insolvency of the MVA, the Legislature will want to establish its priorities for the MVA and determine how best to address the projected insolvency based on these priorities.

Implementation of REAL ID

Increased DMV Workload. Beginning October 1, 2020, Californians must possess a REAL ID that meets minimum identity verification and security standards, in order to access most federal facilities or board federally regulated commercial aircraft, without having to provide other federally accepted documentation. The issuance of REAL IDs in California has led to increased workload and wait times at DMV field offices, as these transactions take longer to process than other transactions. For the past two years, the DMV has received limited‑term state resources to accommodate the additional workload.

Governor’s Budget Request Will Be Updated in Spring. The Governor’s budget includes a “placeholder” request of $63.7 million (MVA) annually from 2019‑20 through 2022‑23 to support 780 positions to continue addressing increased workload for processing REAL IDs. The administration indicates that this request will be updated in the spring after further study of DMV’s workload and processes. We note that there are currently two pending evaluations of DMV that were initiated by the administration—one by the Department of Finance and another by a new DMV Reinvention Strike Team. In order to assist the Legislature in its budget deliberations, we identify in this report some key issues to help ensure that the appropriate level of resources is provided and sufficient legislative oversight is retained.

High‑Speed Rail Project

Project Faces Significant Funding Gap. Since it was approved for bond funding by voters in 2008, the high‑speed rail project has experienced significant cost increases. The project’s 2018 business plan estimates the cost to complete Phase I of the project—from San Francisco to Anaheim—at $77.3 billion. Currently, the project faces an estimated funding gap of over $50 billion to complete Phase I as planned. Recognizing this funding gap, the Governor recently signaled a shift in approach to the project that focuses on using the currently authorized funding to complete a segment between Merced and Bakersfield and the environmental reviews for Phase I. At the time of this analysis, many details of the Governor’s revised approach remain unclear.

Governor’s Revised Approach to Project Presents Key Opportunity for Legislature. We find that the Governor’s revised approach to the high‑speed rail project provides an important opportunity for the Legislature to consider how the project aligns with its policy and fiscal priorities. Given the significant funding gap facing the project, it is a good opportunity for the Legislature to evaluate if it would like to continue to move forward with Phase I of the project as planned or undertake an alternative course of action. As it evaluates the various available options, the Legislature will want to weigh the alternatives’ costs and risks against their anticipated mobility benefits.

Regardless of the approach the Legislature would like to take on the project, we find that there are significant benefits to the Legislature providing clear direction soon. This is because, if the state is going to move forward with the project as currently planned, it would be beneficial to the High‑Speed Rail Authority to have certainty regarding the Legislature’s commitment to completing the project and ensuring its full funding. Alternatively, if the state is ultimately going to scale down the project, the longer the state waits to make this decision, the more likely the state will incur unnecessary costs.

Overview of Governor’s Transportation Budget

The state provides funding for six transportation departments: the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), the California Highway Patrol (CHP), the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV), the High‑Speed Rail Authority, the California Transportation Commission, and the Board of Pilot Commissioners. The California State Transportation Agency has jurisdiction over these six departments and is responsible for coordinating the state’s transportation policies and programs. In addition, the state provides funding to local governments for transportation purposes through “shared revenues” for local streets and roads and the State Transit Assistance program.

Total Proposed Spending of $23.5 Billion. Figure 1 shows the Governor’s proposed spending for the state’s transportation departments and programs from all fund sources—special funds, federal funds, reimbursements, bond funds, and the General Fund. In total, the Governor’s budget proposes $23.5 billion in expenditures for 2019‑20. This is a net increase of $1.4 billion, or 6 percent, over estimated expenditures for the current year. The increase mainly reflects an assumption that a greater amount of expenditures on highway projects will occur in the budget year rather than in the current year (as was previously assumed).

Figure 1

Transportation Budget Summary

(In Millions)

|

Actual |

Estimated |

Proposed |

Change From 2018‑19 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Department/Program |

|||||

|

Department of Transportation |

$9,576 |

$12,665 |

$14,623 |

$1,958 |

15% |

|

Local Streets and Roads |

1,729 |

2,419 |

2,790 |

371 |

15 |

|

California Highway Patrol |

2,406 |

2,545 |

2,786 |

241 |

9 |

|

Department of Motor Vehicles |

1,118 |

1,211 |

1,213 |

2 |

—a |

|

State Transit Assistance |

711 |

950 |

1,048 |

98 |

10 |

|

High‑Speed Rail Authority |

334 |

1,610 |

666 |

‑944 |

‑59 |

|

California State Transportation Agency |

312 |

729 |

399 |

‑330 |

‑45 |

|

California Transportation Commission |

5 |

7 |

9 |

2 |

—a |

|

Board of Pilot Commissioners |

2 |

3 |

3 |

—a |

—a |

|

Totals |

$16,194 |

$22,139 |

$23,536 |

$1,397 |

6% |

|

Fund Source |

|||||

|

Special funds |

$10,256 |

$13,974 |

$15,760 |

$1,787 |

13% |

|

Federal funds |

4,517 |

6,118 |

6,032 |

‑86 |

‑1 |

|

Reimbursementsb |

1,151 |

980 |

1,319 |

339 |

35 |

|

Bond funds |

264 |

1,044 |

339 |

‑705 |

‑68 |

|

General Fund |

5 |

24 |

86 |

62 |

259 |

|

Totals |

$16,194 |

$22,139 |

$23,536 |

$1,397 |

6% |

|

aLess than $500,000 or 0.5 percent. bPrimarily local government payments to Caltrans for roadwork activities. |

|||||

Most Funding From Special and Federal Funds. As shown in the figure, most of the proposed funding for transportation—$21.8 billion (93 percent)—is from special funds and federal funds. Specifically, $15.8 billion in special funds (such as revenues from fuel taxes, vehicle registration fees, and driver license fees) and $6 billion in federal funds. Only $86 million (less than 1 percent) is proposed from the General Fund.

Transportation Bond Debt Service. In addition to the department and program expenditures identified in Figure 1, the state also pays debt service costs on transportation bonds. For 2019‑20, the budget assumes about $1.7 billion in spending on debt service—$167 million (7 percent) higher than the estimated current‑year level. (We note that this spending relates to repaying bonds issued primarily to fund expenditures made in prior years.) Most of the proposed spending—$1.1 billion—is to repay Proposition 1B (2006) bonds that support various highway, local road, and transit projects. Another $445 million is to repay Proposition 1A (2008) bonds for the high‑speed rail project. Funding for debt service primarily comes from truck weight fee revenues.

Motor Vehicle Account (MVA) Fund Condition

The MVA supports the state administration and enforcement of laws regulating the operation and registration of vehicles used on public roads and highways, as well as the mitigation of the environmental effects of vehicle emissions. During the last several years, concerns about the condition of the MVA have arisen as spending from the account has on occasion grown faster than revenues. Below, we (1) provide background information on MVA revenues and expenditures, (2) describe the Governor’s proposals related to the MVA, (3) assess the condition of the MVA, and (4) identify issues for legislative consideration.

Background

MVA Revenues. The MVA receives most of its revenues from vehicle registration fees. In 2018‑19, the MVA is expected to receive a total of $3.9 billion in revenues, with vehicle registration fees accounting for $3.3 billion (86 percent). Vehicle registration fees currently total $86 for each registered vehicle. (We note that the DMV also collects various other fees at the time of registration that are not deposited into the MVA, such as vehicle license fees, truck weight fees, and an additional registration fee specifically for zero‑emission vehicles.) The current $86 registration fee consists of two components:

- Base Registration Fee ($60). The state charges a base registration fee of $60, with $57 going to the MVA and $3 going to two other special funds—the Alternative and Renewable Fuel and Technology Fund ($2), and the Enhanced Fleet Modernization Subaccount ($1). (Under existing state law, the $3 charge included in the base registration fee to support the two other funds is scheduled to sunset on January 1, 2024.) The state last increased the base registration fee in 2016, when it increased the fee by $10 (from $46 to $56). At the same time, the state indexed the fee to the Consumer Price Index (CPI), thereby allowing it to automatically increase with inflation. The inflation adjustment for 2019 increased the fee to the current $60.

- CHP Fee ($26). The state also charges an additional fee of $26 that directly supports CHP. The state last increased this fee in 2014, when it increased the fee by $1 (from $23 to $24) and indexed it to the CPI. The inflation adjustment for 2019 increased the fee to the current $26.

The MVA also receives revenues from driver license fees. These revenues tend to fluctuate based on the number of licenses renewed each year. For 2018‑19, the state is expected to collect $283 million from these fees. The current driver license fee is $36 and is also indexed to the CPI. The remaining MVA revenues primarily come from late fees associated with vehicle registration and driver license renewals, identification card fees, and miscellaneous fees for special permits and certificates (such as fees related to the regulation of automobile dealers and driver training schools).

MVA Transfers. The use of most MVA revenues are limited by the California Constitution to the administration and enforcement of laws regulating the use of vehicles on public highways and roads, as well certain transportation uses. However, roughly $90 million of the miscellaneous MVA revenue sources are not limited by constitutional provisions and, thus, are available for broader purposes. In order to help address the state’s General Fund condition at the time, the Legislature transferred these miscellaneous revenues from the MVA to the General Fund in 2009‑10 on a one‑time basis. A similar transfer was also made on a year‑by‑year basis in the subsequent couple of years, until it was approved as an ongoing transfer beginning in 2012‑13.

MVA Expenditures. The MVA primarily provides funding for three state departments—CHP, DMV, and the California Air Resources Board (CARB)—to support the activities authorized in the California Constitution. Funding supports staff compensation, department operations, and capital expenses. For 2018‑19, a total of about $4 billion is expected to be spent from the MVA, mostly to support CHP and DMV. Unlike for CHP and DMV, a relatively small share of CARB’s total expenditures is supported by the MVA.

Over the past several years, expenditures from the MVA have increased. Specifically, from 2013‑14 to 2018‑19, total MVA expenditures have increased by $1 billion. Some of the major cost drivers include (1) replacement of CHP area offices and DMV field offices, (2) acceptance of driver license applications from persons who are unable to submit satisfactory proof of legal presence in the U.S. (as authorized by Chapter 524 of 2015 [AB 60, Alejo]), and (3) workload related to the issuance of new driver licenses and identification cards that comply with federal standards—commonly referred to as “REAL IDs.”

In addition, we note that supplemental pension plan repayments from the MVA began in 2018‑19. This is related to a 2017‑18 budget action to borrow $6 billion from the state’s cash balances to make a one‑time supplemental payment to the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), which would be repaid from all funds that make employer contributions to CalPERS—including the MVA. (Over the next 30 years, it is anticipated that the MVA is likely to receive savings that outweigh these near‑term loan repayment expenditures, due to slower growth in employer pension contributions.)

Operational Shortfalls in Recent Years. Over the last several years, the MVA has periodically faced operational shortfalls—meaning planned expenditures exceeding combined revenues and transfers. For example, the MVA faced an operational shortfall in 2015‑16 of about $300 million, which was addressed through the one‑time repayment of $480 million in loans that were previously made from the MVA to the General Fund. In 2016‑17, the MVA faced an operational shortfall of roughly the same magnitude and possible insolvency in 2017‑18. In order to address this shortfall and help maintain the solvency of the MVA, the Legislature increased revenues into the account by increasing the base registration fee by $10 in 2016 and indexing it to the CPI (as discussed above).

In the current year, the MVA faces an operational shortfall of almost $400 million. This is because the MVA is expected to have combined revenues and transfers of almost $3.8 billion and expenditures of over $4 billion. (This assumes that DMV’s budget is increased this spring by $40.4 million to alleviate customer wait times in field offices as intended by the Director of Finance pursuant to provisional language in the 2018‑19 Budget Act.) In order to address the projected shortfall in 2018‑19, the MVA will need to draw down its fund balance that has accumulated in prior years. Absent corrective actions, the account would likely again experience an operational shortfall in 2019‑20 and potentially become insolvent in the future.

Governor’s Proposals

In recognition of the estimated operational shortfalls facing the MVA—particularly in the current year—and the likelihood that the account will become insolvent, the Governor’s budget includes various proposals that are intended to benefit the MVA. Specifically, the budget proposes to:

- Shift From “Pay‑As‑You‑Go” to Financing for CHP Area Office Replacements. The state has typically funded the replacement of CHP area offices from the MVA on a pay‑as‑you go basis. The Governor’s budget proposes to finance the replacement of three CHP area offices through the Public Buildings Construction Fund, rather than with pay‑as‑you‑go as they were initially approved by the Legislature. The financing of the projects would be repaid from the MVA over many years. Under the Governor’s proposal, a total of $129 million in previously authorized funds would revert to the MVA. (We discuss the proposal in more detail in the “California Highway Patrol” section of this report.)

- Shift Certain One‑Time MVA Expenditures to the General Fund. The Governor’s budget includes a one‑time total General Fund augmentation of $77.1 million—$74.1 million for CHP and $3 million for DMV—to support a variety of proposals that would have otherwise been funded from the MVA. For example, the budget proposes $44.5 million from the General Fund to replace radio communications systems in CHP vehicles, as well as $8 million in General Fund support for deferred maintenance projects at CHP ($5 million) and DMV ($3 million).

- Suspend Certain CHP and DMV Capital Outlay Projects. The Governor’s budget proposes to suspend two planned area office replacement projects in Quincy and Santa Ana, and revert $37 million in previously authorized funds to the MVA. In addition, the budget proposes to suspend the planned replacement of the Inglewood DMV field office and construction of perimeter fencing at 20 existing DMV field offices, and revert $25 million in previously authorized funds for these projects to the MVA.

We note that the Governor’s budget also includes a few proposals that would increase MVA expenditures in 2019‑20 and beyond. The largest of which is $63.7 million annually for four years to DMV for workload related to REAL ID. (As we discuss in the “Department of Motor Vehicles” section of this report, the proposed level of resources is essentially a “placeholder” that the administration intends to update in the spring after further study of DMV’s workload and processes.)

MVA Projected to Become Insolvent in 2021‑22

While the Governor’s budget proposals to shift from pay‑as‑you‑go to financing certain CHP area office replacement projects, shift certain MVA expenditures to the General Fund, and suspend certain CHP and DMV capital outlay projects would help alleviate the operational shortfalls in the MVA in the current year and over the next few years, they would not fully address the account’s structural imbalance. Specifically, the Department of Finance’s (DOF’s) five‑year projection (2019‑20 through 2023‑24) estimates that the MVA’s fund balance will be depleted by 2021‑22—resulting in insolvency. These projections reflect expenditures already approved by the Legislature and those proposed by the Governor (such as those described above). We note that the projections reflect estimated increases in various employee‑related costs for CHP officers.

Figure 2 compares total MVA resources (revenues, transfers, and fund balances) with expenditures from 2018‑19 through 2023‑24. As shown in the figure, absent any corrections, the administration projects that the MVA would become insolvent in 2021‑22 with a shortfall of roughly $40 million that grows to roughly $150 million in 2022‑23. As previously indicated, existing reserves help prevent the fund from becoming insolvent prior to 2021‑22.

We also note that various additional cost pressures could further impact the solvency of the MVA through the end of the forecast period (2023‑24). For example, as indicated above, the Governor’s budget essentially includes a placeholder of $63.7 million annually for four years to accommodate workload related to REAL ID. It is possible that the actual workload costs could be much higher. Similarly, the increased employee costs for CHP officers could be higher than assumed. In addition, the Governor has expressed an interest in making it possible for individuals visiting DMV field offices to pay any necessary fees with a credit card, such as vehicle registration fees. To the extent that the department’s current policy of not passing on credit card transaction processing costs to members of the public when they pay existing DMV fees online was extended to those visiting field offices, allowing credit card transaction in field offices would further increase MVA costs.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

The Legislature will want to establish its priorities for the MVA and determine how best to address the projected insolvency based on these priorities. While the MVA is not projected to become insolvent until 2021‑22, we recommend the Legislature begin to take steps now to prevent the insolvency. While the Governor’s budget proposals would help improve the condition of the MVA, there are alternatives, as well as additional steps that could be taken. We note that to the extent the Legislature rejects the Governor’s proposed changes regarding planned CHP and DMV capital outlay projects, the MVA would become insolvent beginning in 2020‑21—a year sooner that under the Governor’s plan—with a shortfall of roughly $60 million. In developing its plan for addressing the projected insolvency of the MVA, the Legislature will want to consider the impacts on the MVA beyond the administration’s forecast period of the next five years. For example, several years ago, the state initiated a long‑term plan to replace existing CHP and DMV offices. Although the Governor’s budget proposes to suspend certain office replacement projects, those projects and the ones currently planned for future years will eventually result in increased MVA costs in the long run.

In order to assist the Legislature in developing its plan and mix of strategies for addressing the MVA’s condition—both in the near and long term, we identify the following options for its consideration:

- Amend Supplemental Pension Plan Repayment Schedule. Working with the administration, the Legislature could amend the MVA’s repayment schedule to focus more repayments in the latter years and reduce the required repayments over the next few years. The administration’s MVA projections include its estimates for annual repayments, which are estimated to moderately grow from $62 million in 2019‑20 to $72 million in 2023‑24. While amending the schedule of these loan repayments would increase costs in the latter years, it would provide immediate relief to the MVA in the near term. (Under current law, the principal and interest of the loan must be repaid by June 30, 2030.) This could be particularly beneficial to accommodate some of the increased cost pressures on the MVA that are not ongoing, such as the increased workload associated with the implementation of REAL ID.

- Eliminate General Fund Transfer. As mentioned earlier, the MVA receives roughly $90 million in miscellaneous revenues that are not limited in their use by the California Constitution. Currently, these revenues are transferred to the General Fund, making them unavailable to support MVA expenditures. The Legislature could eliminate this practice in order to keep these revenues in the MVA, particularly given that these funds were initially transferred by the Legislature on a temporary basis to help address the state’s General Fund condition at the time. Given that the Governor’s budget proposes a total of $77.1 million from the General Fund on a one‑time basis to support CHP and DMV costs that would otherwise have been funded from MVA, we note that undoing the $90 million General Fund transfer would effectively only have about a $13 million impact on both the MVA and General Fund in 2019‑20. After 2019‑20, however, such an action would provide $90 million on an annual basis to support MVA expenditures.

- Increase MVA Revenues. The Legislature could generate additional revenues by increasing vehicle registration or driver license fees—either on a limited‑term or ongoing basis. In determining whether to increase such fees, the Legislature will want to consider the potential fiscal impacts on drivers and vehicle owners. We estimate that roughly $30 million in additional revenue could be generated annually from a $1 increase in the base vehicle registration, and roughly $6 million from a $1 increase in the driver license fee. Accordingly, if the Legislature wanted to increase the vehicle registration fee to fully address the structural imbalance of the MVA and begin to build a reserve, it would need to do so by a $5 increase. Alternatively, the Legislature could increase existing fees in combination with other actions.

- Implement DMV Efficiencies. As we discuss in more detail later in this report, two evaluations of DMV’s operational processes are already in process—one by DOF and one lead by the Government Operations Agency. The Legislature may want to consider directing the department and agency to submit a report at spring budget hearings on potential efficiencies. This would allow the Legislature to consider all of the potential efficiencies that have been identified thus far and their impact on MVA expenditures, as well as potential statutory changes that may need to be enacted to implement certain efficiencies.

Caltrans

Caltrans is responsible for planning, coordinating, and implementing the development and operation of the state’s transportation system. The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $14.6 billion for Caltrans in 2019‑20. This is $2 billion, or about 15 percent, higher than the estimated current‑year expenditures. The higher level is primarily the result of changes in the timing of capital outlay expenditures and increases in overall transportation revenues available for capital outlay projects and mass transportation as a result of Chapter 5 of 2017 (SB 1, Beall).

Figure 3 shows proposed expenditures by program and fund source. Most spending supports the department’s highway program and comes from various state special funds (which mainly receive revenues from fuel taxes and vehicle fees) as well as federal funds. The total level of spending proposed for Caltrans in 2019‑20 supports about 20,600 positions. Changes to the funding and staffing requested for capital outlay support are not included in the January budget proposal and will instead be provided in May consistent with the department’s past practice.

Figure 3

Caltrans Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Actual |

Estimated |

Proposed |

Change From 2018‑19 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Program |

|||||

|

Highways |

|||||

|

Capital outlay projects |

$2,901 |

$3,788 |

$5,258 |

$1,470 |

39% |

|

Local assistance |

1,682 |

2,971 |

2,802 |

‑169 |

‑6 |

|

Maintenance |

2,261 |

2,222 |

2,074 |

‑148 |

‑7 |

|

Capital outlay support |

1,679 |

2,104 |

2,103 |

— |

— |

|

Other |

462 |

510 |

489 |

‑21 |

‑4 |

|

Subtotals |

($8,985) |

($11,594) |

($12,725) |

($1,131) |

(10%) |

|

Mass transportation |

$323 |

$757 |

$1,584 |

$827 |

109% |

|

Other |

268 |

314 |

314 |

— |

— |

|

Totals |

$9,576 |

$12,665 |

$14,623 |

$1,958 |

15% |

|

Fund Source |

|||||

|

Special funds |

$4,188 |

$5,709 |

$7,403 |

$1,694 |

30% |

|

Federal funds |

4,340 |

5,974 |

5,876 |

‑98 |

‑2 |

|

Reimbursements |

1,001 |

844 |

1,183 |

339 |

40 |

|

Bond funds |

47 |

138 |

161 |

23 |

17 |

|

Totals |

$9,576 |

$12,665 |

$14,623 |

$1,958 |

15% |

Governor’s Proposals. The Governor’s budget for 2019‑20 does not propose any new major initiatives for Caltrans and includes only a few budget change proposals for the department. For example, the budget includes a total of about $2 billion in SB 1 funding for highway maintenance and repair, bridge and culvert repairs, enhancements to the state’s trade corridors, and various other activities. This proposal is consistent with the continued implementation of SB 1. The Governor’s budget also proposes a total of $85.7 million (State Highway Account) and 407 positions to work on roughly 700 Project Initiation Documents (PIDs) in 2019‑20, with roughly half of them expected to be completed in that year. (A PID is completed during the preparation of the initial plan for a highway capital project and includes the estimated cost and scope of the project, as well as the identification of the transportation problem that is to be addressed and an evaluation of alternatives to address the problem.) The proposed level of PID funding is an increase of $4.9 million from the 2018‑19 level and reflects the department’s changing PID workload resulting from the continued implementation of SB 1.

California Highway Patrol

The primary mission of the CHP is to ensure safety and enforce traffic laws on state highways and county roads in unincorporated areas. The CHP also promotes traffic safety by inspecting commercial vehicles, as well as inspecting and certifying school buses, ambulances, and other specialized vehicles. The CHP carries out a variety of other mandated tasks related to law enforcement, including investigating vehicular theft and providing backup to local law enforcement in criminal matters. The operations of the CHP are divided across eight geographic divisions throughout the state.

The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $2.8 billion in 2019‑20, which is about $241 million, or 9 percent, more than the revised current‑year estimate. The year‑over‑year increase is mainly the result of the Governor’s proposals to spend: (1) $133 million (nearly all from the Public Buildings Construction Fund) for capital outlay expenditures to replace area offices, and (2) $87 million (primarily from the General Fund) to replace radio communications equipment and information technology (IT) infrastructure.

Governor’s Proposals

The Governor’s budget for 2019‑20 includes various new spending requests that cite projected shortfalls in the MVA as their rationale. For example, the Governor’s budget includes five proposals that would reduce the impact on the MVA of the CHP’s area office replacement program. The budget plan also proposes to use General Fund to purchase radio communications equipment and IT infrastructure that typically are purchased with funds from the MVA. Below, we describe the Governor’s proposals in more detail.

Shift to Public Buildings Construction Fund Financing for CHP Area Office Replacements. The Governor’s budget proposes to shift from a pay‑as‑you‑go approach for the design‑build phase of three CHP area office replacement projects in El Centro, Hayward, and San Bernardino to financing the projects through the Public Buildings Construction Fund. (The financing costs for these projects would ultimately be repaid from the MVA.) Under the Governor’s proposal, $129 million in previously authorized funds would revert to the MVA, and new funding of $133 million ($132 million in Public Buildings Construction Fund authority and $731,000 from the MVA) would be authorized. (The $4.6 million difference between the total proposed funding and previously authorized funds is due to: [1] cost increases for the design‑build phase for the El Centro Office [$1.6 million], Hayward office [$641,000], and San Bernardino office [$1.6 million], and [2] funding for the performance criteria phase for the El Centro office [$143,000], Hayward office [$143,000], and San Bernardino office [$445,000] in case certain documents need to be resubmitted.) Specifically, the Governor’s budget requests $133 million in Public Buildings Construction Fund authority as follows:

- El Centro. $41.9 million from the Public Buildings Construction Fund for the design‑build phase of the El Centro area office replacement. The proposed facility would be 27,481 square feet, or about five‑to‑six times the size of the existing 4,575 square foot facility that was built in 1966. The total estimated cost to replace this area office is estimated at $45.2 million (includes $3.3 million for acquisition and planning provided in the 2016‑17 budget).

- Hayward. $48.7 million from the Public Buildings Construction Fund for the design‑build phase of the Hayward area office replacement. The proposed facility would be 48,000 square feet, or about four times the size of the existing 11,033 square foot facility that was built in 1971. The total estimated cost to replace this area office is estimated at $50.7 million (includes $2 million for acquisition and planning provided for in the 2016‑17 budget).

- San Bernardino. $42 million from the Public Buildings Construction Fund for the design‑build phase of the San Bernardino area office replacement. The proposed facility would be 44,000 square feet, or about three‑to‑four times the size of the existing 12,253 square foot facility that was built in 1973. The total estimated cost to replace this area office is estimated at $47.6 million (includes $5.6 million for acquisition and planning provided in the 2016‑17 budget).

Revert MVA Funds for Two CHP Area Office Replacements and Suspend the Projects. The Governor’s budget proposes to suspend area office replacement projects in Quincy and Santa Ana and revert funding that was provided for various phases of these two projects. Specifically, the Governor’s budget requests the reversion of $37 million in MVA authority as follows:

- Quincy. $36.9 million that was appropriated in the 2018‑19 budget for the design‑build phase of an area office replacement project in Quincy.

- Santa Ana. $350,000 ($250,000 for acquisition, and $100,000 out of a total of $250,000 for study) that was appropriated in the 2017‑18 budget for an area office replacement project in Santa Ana.

Replace Radio Equipment and IT Infrastructure. The Governor’s budget requests $87 million ($69 million General Fund) on a one‑time basis to replace outdated radio communications equipment and upgrade IT infrastructure as follows:

- Radios. $62.5 million ($44.5 million General Fund and $18 million from the Special Deposit Fund‑Asset Forfeiture Accounts) to replace 3,600 radio communications systems in CHP vehicles.

- Multifunction Tablets. $15 million General Fund to replace laptops and hand‑held citation devices with 3,075 multifunction tablets that will allow officers to use a single device for electronic citations, and provide full access to departmental software applications for filing reports and other purposes.

- IT Infrastructure. $9.5 million General Fund to replace aging IT infrastructure and provide increased storage capacity, connectivity, and security.

Convene Regional Property Crimes Task Force. The Governor’s budget proposes one and one‑half year funding of $5.8 million General Fund for 16 positions and $2.1 million in consulting services. (The DOF indicated in discussions that it will propose language to extend the task force’s duration to two years.) The CHP proposes to use these resources to convene a regional property crimes task force in conjunction with the Department of Justice, as required under Chapter 803 of 2018 (AB 1065, Jones‑Sawyer). The task force would support local law enforcement in counties with elevated levels of property crime including organized retail theft and vehicular burglary.

Fund Deferred Maintenance. The Governor’s budget proposes one‑time funding of $5 million General Fund to complete high‑priority projects from the CHP’s list of pending deferred maintenance projects. This list includes over 450 projects with an estimated cost of more than $44 million to complete. For example, the project list includes the repair and replacement of security camera systems and repairing fencing at various locations.

LAO Comments

In our review of the Governor’s budget proposals, we find that the proposals to replace radio equipment and IT infrastructure, as well as reduce CHP’s deferred maintenance backlog, are reasonable given the identified needs. While these costs have typically been funded from the MVA, given the structural imbalance facing the MVA, the proposal to instead provide one‑time General Fund support is also reasonable.

The Governor’s proposal to shift from a pay‑as‑you‑go approach to Public Buildings Construction Fund for the design‑build phase of three previously approved area office replacement projects would reduce MVA expenditures by $129 million (in previously authorized funds that would revert back to the MVA). This would help improve the condition of the MVA over the next several years. However, last year the Legislature rejected a similar approach and funded these costs on a pay‑as‑you‑go basis. Similarly, the proposal to suspend two area office replacement projects would reduce MVA expenditures by $37 million, thereby helping to improve the condition of the MVA. However, if the projects are suspended, there will still be a clear need to replace both of these area offices.

As we discussed earlier in this report, the Legislature will want to establish its priorities for the MVA and how best to address the projected insolvency based on these priorities. While the Governor’s budget proposals would help improve the condition of the MVA, there are alternatives, as well as additional steps that could be taken—including the various options we identified in the “MVA Fund Condition” section of this report, such as eliminating the current transfer from the MVA to the General Fund and increasing the vehicle registration or driver license fees.

Department of Motor Vehicles

The DMV is responsible for registering vehicles, issuing driver licenses, and promoting safety on California’s streets and highways. Additionally, DMV licenses and regulates vehicle‑related businesses (such as automobile dealers and driver training schools), and collects certain fees and taxes for state and local agencies. As of January 2019, there were 27.1 million licensed drivers and 35.6 million registered vehicles in the state.

The Governor’s budget includes $1.2 billion for DMV in 2019‑20, which is roughly the same as the estimated level of spending in the current year. About 95 percent of all DMV expenditures are supported from the MVA, which generates its revenues primarily from vehicle registration and driver license fees. The level of spending proposed for 2019‑20 supports about 8,300 positions at DMV.

Governor’s Proposals

Overview of Major Proposals. The Governor’s budget for 2019‑20 includes various proposals that are intended to help address the projected shortfalls in the MVA. For example, the budget proposes to delay certain DMV capital outlay projects and use General Fund to support deferred maintenance costs that have typically been funded from the MVA. At the same time, the budget includes a few proposals to increase MVA expenditures. In addition, the budget includes increased spending from non‑MVA transportation funds.

The Governor’s major proposals include the following:

- Suspension of Certain Capital Outlay Projects. The budget proposes to suspend certain capital outlay projects and revert $25 million to the MVA that was previously authorized for these projects. This amount consists of $15.1 million related to the replacement of the Inglewood Field Office and $9.9 million related to perimeter security fences at about 20 field office locations.

- Deferred Maintenance Funding. The budget includes a one‑time $3 million General Fund augmentation to partially address a deferred maintenance backlog in DMV field offices and facilities. DMV reports that it plans on using these funds for roofing and heating, ventilation, and air conditioning projects. We note that DMV’s deferred maintenance projects have typically been funded from the MVA.

- Implementation of REAL ID. The budget includes a “placeholder” request of $63.7 million (MVA) annually from 2019‑20 through 2022‑23 to support 780 positions to continue addressing increased workload for processing REAL IDs. (We discuss this proposal, as well as a pending request for an additional $40.4 million in 2018‑19, in more detail below.)

- Continuation of Certain Capital Outlay Projects. The budget includes $1 million ($694,000 ongoing) from the MVA for a new lease for the Walnut Creek Field Office. It also includes a one‑time $1.2 million augmentation from the MVA to support the working drawings phase to continue the replacement of the Reedley Field Office.

- High‑Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) Lane Stickers (SB 957). The budget includes a total of about $15 million from the MVA over five years ($3 million in 2019‑20) to implement Chapter 367 of 2018 (SB 957, Lara), which allows owners of particular vehicles who meet certain requirements to obtain a sticker from DMV that would allow them to operate the vehicle in HOV lanes with fewer occupants than required. These costs are expected to be fully offset by fees paid by individuals who apply for an HOV lane sticker.

- Credit Card Processing Fees for Transportation Improvement Fee (TIF). Senate Bill 1 imposed an additional fee—the TIF—upon the registration or renewed registration of most vehicles. More individuals than expected are choosing to pay this fee using credit cards. As such, the budget includes an $8.5 million augmentation (growing to $8.9 million ongoing) from the Road Maintenance and Rehabilitation Account to address increased credit card processing fees.

LAO Comments. In our review of the Governor’s budget proposals, we find that the proposals for additional resources to address increased costs for processing TIF credit card transactions, to support increased workload from implementing new HOV lane sticker legislation, and to reduce DMV’s deferred maintenance backlog are reasonable given the identified workload needs and reflect legislative priorities in recent years. We also find the department has justified the need for the continuation of two field office projects. Finally, we note that the proposals to suspend certain capital outlay projects increases the level of resources available in the MVA by $25 million and helps address the solvency of the fund in the budget year.

However, as we discussed previously, the MVA is still projected to become insolvent in 2020‑21 despite the various actions (such as suspending certain capital outlay projects) taken to help address its immediate solvency. As such, the Legislature will want to establish its priorities for the MVA and how best to address the projected insolvency based on these priorities. The Legislature can also consider other alternative actions that can be taken—including the various options we identified in the “MVA Fund Condition” section of this report—to help further address the MVA insolvency.

In the next section, we provide an update on REAL ID implementation, discuss the administration’s various proposals related to REAL ID implementation and DMV operations, and provide comments for legislative consideration.

REAL ID Workload

Background

REAL ID Act. The federal government enacted the REAL ID Act in 2005 that requires state‑issued driver licenses and identification (ID) cards to meet minimum identity verification and security standards in order for them to be accepted by the federal government for official purposes—such as accessing most federal facilities or boarding federally regulated commercial aircraft. Driver licenses and ID cards issued by noncompliant states were no longer able to be used to board domestic airplanes as of January 22, 2018. Those issued by states that are compliant or have received an extension from the federal government to comply may continue to be used until October 1, 2020. After this date, only REAL ID compliant driver licenses or ID cards can be used to board domestic airplanes. However, other forms of federally acceptable forms of ID (such as a passport) may be used instead.

Approximately 38 states have been deemed REAL ID complaint, while most of the remaining states—such as California—have received an extension. Federal law authorizes the Secretary of Homeland Security to grant extensions of time to individual states to comply with the REAL ID Act if they provide sufficient justification that more time is needed. California has regularly received such extensions since it began implementation in early 2018. The most recent extension extends through April 10, 2019.

Impact of REAL ID Implementation on DMV. California began issuing REAL ID compliant driver licenses and ID cards in January 2018 and reports having issued nearly 2.5 million through the end of 2018. (For comparison, 6.5 million noncompliant driver licenses and ID cards were issued during the same period.) Individuals seeking compliant driver licenses and ID cards are required to visit a field office and provide certain specified documents that must be verified and scanned. This has led to increased workload at DMV field offices, as these transactions take longer to process than noncompliant transactions. Additionally, more individuals—such as those who would otherwise have renewed their licenses by mail or those whose licenses expire after the October 2020 federal deadline—are visiting field offices to obtain compliant driver licenses or ID cards.

Despite receiving additional funding to support this increased workload (as discussed below), DMV field offices began reporting a significant increase in wait times. At its peak, some individuals visiting certain offices could experience wait times of a few hours. According to the DMV, wait times in the month of December 2018 decreased to an average of 44 minutes for individuals without appointments and an average of 13 minutes for those with an appointment. DMV achieved these reduced wait times through various actions, including hiring temporary workers, extending field office hours, and expanding the number of self‑service terminals available for individuals to conduct transactions outside of field offices or without the assistance of DMV staff.

Funding DMV Workload. To support the increased workload related to REAL ID, the state has provided additional resources to DMV. Specifically, DMV received $23 million from the MVA to support 218 positions in the 2017‑18 budget and $46.6 million to support 550 positions in the 2018‑19 budget. Given the uncertainty in actual workload, funding was provided on a limited‑term basis through the end of the current year. The 2018‑19 budget also included provisional language that authorized DOF to provide DMV with additional resources as needed no sooner than 30 days following notification to the Joint Legislative Budget Committee (JLBC). An additional $16.6 million and 230 positions were requested and provided pursuant to this authorization in August 2018 in order to help DMV reduce the significant wait times in the field offices. This means that funding for REAL ID workload in 2018‑19 currently totals $63.2 million to support 780 positions.

Additionally, DOF has submitted a subsequent notification to the JLBC that it intends to provide DMV with an additional $40.4 million to maintain existing wait times in the current year no earlier than April 30, 2019. This amount consists of (1) $17.5 million for additional expenditures in the first six months of the current year and (2) $22.9 million for additional expenditures in the remaining portion of the year. DMV reports that this funding will be used to support an additional 120 positions, as well as to maintain all activities enacted to date (such as the extension of field office operational hours).

Governor’s Proposal

Placeholder Budget Request. The Governor’s 2019‑20 budget includes $63.7 million annually through 2022‑23 from the MVA to support 780 positions—the same level of resources provided to DMV in the current year. However, the administration clearly indicates that this request will be updated in the spring after further study of DMV’s workload and processes.

Pending Evaluations. The administration anticipates that its spring request for additional DMV resources may be informed by currently pending evaluations of DMV. For example, the request may reflect operational changes identified by these evaluations to help DMV operate more efficiently. These pending evaluations include:

- DOF Performance Audit. In September 2018, Governor Brown directed DOF’s Office of Audits and Evaluations to conduct a performance audit of DMV’s IT and customer service functions. DOF expects to (1) evaluate DMV’s current operations and efforts to address its aging IT infrastructure and (2) make recommendations to improve DMV’s operations and enhance its customer service. A full report is expected to be released in March 2019. However, in January 2019, Governor Newsom ordered an accelerated review of early findings within 30 days.

- DMV Reinvention Strike Team. In January 2019, Governor Newsom tasked the Government Operations Agency Secretary to lead a new DMV Reinvention Strike Team. While specific details are still forthcoming, the team is expected to (1) examine DMV operations with an emphasis on various factors such as worker performance and customer satisfaction and (2) make recommendations to modernize and reinvent the DMV.

Proposed Future Evaluation. The Governor’s 2019‑20 budget proposes to create the Office of Digital Innovation within the Government Operations Agency. The purpose of this new office is to develop and enforce requirements for departments to assess their service delivery models, to reengineer how they deliver customer service, and leverage digital innovation where appropriate. The administration expects that DMV will be the first state department to work with the office in 2019‑20.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

As discussed above, the administration plans to submit a revised budget proposal to support DMV’s REAL ID workload this spring. In order to assist the Legislature in its deliberations, we identify below some key issues to help ensure that the appropriate level of resources is provided and sufficient legislative oversight is retained.

Examine Changes That Can Generate More Immediate Impact. The pending and proposed evaluations could generate significant long‑term benefit to the extent DMV implements changes to operate more efficiently and provide better customer service. However, some of these identified changes may take time to fully implement and to achieve benefit. Given the October 2020 deadline for REAL ID compliance, DMV field offices are likely to experience similar or increased levels of individuals seeking REAL ID compliant driver licenses and ID cards in the budget year. As such, identifying changes that can generate more immediate impact could help DMV operate more cost‑effectively at the start of the budget year. For example, it is possible that additional or improved outreach efforts could increase the number of individuals arriving in field offices with completed electronic driver license and ID applications and all Real ID required documentation—thereby reducing overall transaction times.

Consider Directing DOF and DMV Reinvention Strike Team to Report at Spring Budget Hearings. To help the Legislature with its evaluation of the administration’s proposed level of DMV resources, the Legislature could consider requiring DOF and the DMV Reinvention Strike Team to submit a report at spring budget hearings on potential operational efficiencies. This would allow the Legislature to examine and evaluate all of the potential efficiencies that have been identified thus far—not just those selected by the administration. The Legislature can then determine which of these, or other identified efficiencies or operational changes, it would like to implement. Such actions could help reduce the total amount of additional funding needed to address REAL ID workload or other DMV workload in the coming years. This is particularly important given the pending insolvency of the MVA.

Consider Level of Appropriate Oversight. Regardless of how much funding is ultimately included in the budget for DMV REAL ID operations, the Legislature will want to consider what level of legislative oversight would be appropriate. For example, as stated above, DMV recently reported spending $17.5 million more in the first six months of the current year than expected and anticipates needing additional funding before the end of the current year. The Legislature may want to require DMV to seek legislative approval before incurring such spending to allow the Legislature to examine the reasons for the increased expenditures and determine what action, if any, it would like to take.

High‑Speed Rail Authority

Chapter 796 of 1996 (SB 1420, Kopp) established the High‑Speed Rail Authority (HSRA) to plan and construct a high‑speed rail system that would link the state’s major population centers. HSRA is governed by a nine‑member board appointed by the Legislature and Governor. In addition, HSRA has an executive director, appointed by the board, and a staff of about 226. Most work is carried out by consultants under contracts with HSRA. In November 2008, voters approved Proposition 1A, which specified certain conditions that the system must ultimately achieve, as well as authorized the state to sell bonds to partially fund the system.

The Governor’s budget proposes a total of $666 million in 2019‑20 for HSRA, a decrease of $944 million (or 59 percent) below the estimated level of funding in 2018‑19. The reduction primarily reflects $677 million in one‑time funding provided in 2018‑19 for local “bookend” projects. (We describe these bookend projects below.) We note that the Governor’s budget proposes ten positions and about $4 million from Proposition 1A in 2019‑20 and ongoing to support two IT‑related proposals.

Update on High‑Speed Rail Project

In this section, we provide (1) background information on the project, (2) an update on its status, (3) summarize HSRA’s most recent business plan, (4) summarize the findings of a recent audit by the California State Auditor on the project, and (5) identify issues for legislative consideration.

Background

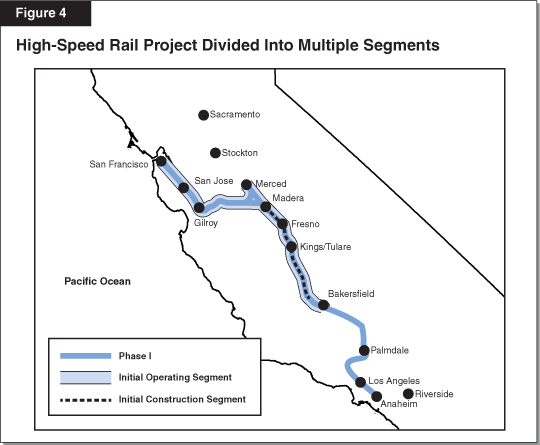

Project Delivery Plan. The high‑speed rail project is divided into two phases. Phase I would provide service for about 500 miles from San Francisco to Anaheim. Phase II would connect the system to Sacramento in the north and San Diego in the south. As shown in Figure 4, delivery of Phase I is divided into multiple segments with the state’s first high‑speed rail operations beginning on a segment connecting San Francisco and Bakersfield. This initial operating segment (IOS)—commonly referred to as the Valley‑to‑Valley line—is expected to be completed in 2029 and cost about $29.5 billion. The IOS is itself divided into multiple segments, beginning with the initial construction segment (ICS), which extends for 119 miles through the Central Valley from Madera (about 25 miles north of Fresno) to Shafter (about 20 miles north of Bakersfield). HSRA currently estimates the ICS will be completed by 2022 and cost $10.6 billion.

Bookend and Connectivity Projects. HSRA has partnered with local authorities to initiate a variety of bookend and “connectivity” projects on commuter rail lines in the Bay Area and Southern California that will facilitate high‑speed rail, as well as provide benefits to existing rail and transit systems. These projects include the planned electrification of the Caltrain corridor to allow for high‑speed rail to share Caltrain’s tracks, a major grade separation project near Los Angeles, and an upgrade to Los Angeles’ Union Station.

Project Funding. The high‑speed rail project has received funding from three main sources:

- Proposition 1A Bonds. Proposition 1A authorized the state to sell about $10 billion in general obligation bonds to support the development of the high‑speed rail system, including associated bookend and connectivity projects. This includes $9 billion for the planning and construction of the high‑speed rail system itself, with the remainder to support the connectivity projects discussed above. (Of this $9 billion, HSRA has set aside $1.1 billion as contributions to locally administered bookend projects and $450 million for project administration.) At this time, the Legislature has appropriated $5.5 billion in Proposition 1A bond funds, with about $2.7 billion having been spent—$2 billion on the high‑speed rail project and about $700 million on connectivity projects.

- Federal Funds. The federal government has awarded HSRA a total of $3.5 billion, subject to certain matching requirements and project deadlines. First, the state received $2.6 billion in American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) funds in 2009. The funding agreement for these funds requires the state to provide $2.5 billion in matching funds, but allows the state to spend down the federal funds in advance of the state match. HSRA fully expended the ARRA funds and expects to complete the state match requirement in 2019‑20. Second, the state received a $929 million grant from the federal High‑Speed Intercity Passenger Rail program in 2010 (commonly referred to as the FY10 Federal Grant), which expires at the end of 2022 and requires a state match of $360 million. The state must meet certain conditions under the FY10 Federal Grant agreement, including (1) completing its match to the ARRA grant before it can spend these funds, (2) using the funds to support infrastructure that provides intercity passenger rail service, and (3) completing all environmental reviews for Phase I of the high‑speed rail project by 2022. The grant agreement also includes a provision that allows the federal government to terminate the grant under certain conditions, such as failing to make reasonable progress on the project. On February 19, 2019, the federal government notified the state of its intention to terminate the FY10 grant under this provision.

- Cap‑and‑Trade Auction Revenue. In 2014, the state began providing cap‑and‑trade auction proceeds to HSRA for the high‑speed rail project. (Cap‑and‑trade auction proceeds are revenue generated by the state from the sale of emissions allowances as part of the state’s efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.) This includes $650 million in one‑time cap‑and‑trade revenues, as well as the continuous appropriation of 25 percent of cap‑and‑trade revenues, beginning in 2015‑16. To date, the project has received about $2.4 billion in cap‑and‑trade revenues and spent about $600 million of these funds.

Project Status

Environmental Review. In planning and designing the high‑speed rail system, HSRA must comply with both the California Environmental Quality Act and the National Environmental Policy Act. Both laws require environmental reviews to assess the extent to which the high‑speed rail project could cause significant environmental impacts. For environmental review purposes, HSRA has divided the high‑speed rail project into 12 project sections. The boundaries of these sections do not necessarily align with the boundaries of the project’s segments. As shown in Figure 5, HSRA has completed the environmental reviews for the Merced‑to‑Fresno and Fresno‑to‑Bakersfield sections. The environmental reviews for the remainder of Phase I are currently underway, while the environmental reviews for Phase II have not yet started.

Figure 5

Anticipated Schedule for Completing Environmental Reviews of High‑Speed Rail Project

|

Project Section |

Date |

|

Phase I |

|

|

San Francisco to San Jose |

March 2021 |

|

San Jose to Merced |

November 2020 |

|

Merced to Fresno |

Completed |

|

Portion requiring separate review: Central Valley Wye |

November 2019 |

|

Fresno to Bakersfield |

Completed |

|

Portion requiring separate review: locally generated alternative |

April 2019 |

|

Bakersfield to Palmdale |

June 2020 |

|

Palmdale to Burbank |

January 2021 |

|

Burbank to Los Angeles |

July 2020 |

|

Los Angeles to Anaheim |

January 2020 |

|

Phase II |

|

|

Los Angeles to San Diego |

To Be Determined |

|

Merced to Sacramento |

To Be Determined |

Right‑of‑Way Acquisition. Once the alignment of a section is finalized and the relevant environmental review of a project section is complete, HSRA can acquire the right‑of‑way in that section as needed for construction subject to funding availability. Because HSRA has finalized the alignment and completed the environmental reviews of the sections between Merced and Bakersfield, it is able to acquire right‑of‑way in those sections. However, HSRA has yet to finalize the alignments and designs for potential construction beyond the ICS, and therefore has not yet begun acquiring right‑of‑way beyond the ICS. As of January 2019, HSRA has identified 1,838 parcels of land necessary for construction of the ICS and has acquired 1,392 of them. HSRA estimates completing right‑of‑way acquisition for the ICS by 2020.

Project Construction. In 2015, HSRA initiated construction on the ICS. To date, HSRA has spent about $3.8 billion on construction of the ICS. This includes the completion of major structures, such as the construction of the Fresno River Bridge and Tuolumne Street Bridge, and the realignment of a portion of State Route 99. As indicated above, HSRA currently estimates it will complete the ICS by 2022.

2018 High‑Speed Rail Business Plan

State law requires HSRA to prepare a business plan every even year that provides certain key information about the project and planned system, such as ridership, cost, and schedule information. Additionally, state law requires HSRA to prepare a project update report every odd year that provides certain updated information, such as on costs and schedule. In June 2018, HSRA adopted its 2018 business plan. (The 2019 project update report is required to be submitted by March 1, 2019.) As shown in Figure 6, the 2018 business plan estimates the cost of completing construction of Phase I at $77.3 billion, which is $13.1 billion higher than the 2016 cost estimate. This estimate includes $29.5 billion to complete the construction of the IOS (Valley‑to‑Valley line).

Figure 6

HSRA’s Estimated Construction Costs for Phase I

(In Billions)

|

Project Component |

Cost |

|

Initial Operating Segment |

|

|

Initial construction segment |

$10.6 |

|

San Jose to Gilroy |

3.2 |

|

Gilroy to Carlucci Road |

10.2 |

|

Carlucci Road to Madera |

2.4 |

|

San Francisco and Bakersfield extensions |

1.9 |

|

Rolling stock |

1.1 |

|

Subtotal |

($29.5) |

|

San Francisco to San Jose |

$2.1 |

|

Merced to Wye |

2.4 |

|

Bakersfield to Palmdale |

16.3 |

|

Palmdale to Burbank |

17.5 |

|

Burbank to Los Angeles |

1.5 |

|

Los Angeles to Anaheim |

3.6 |

|

Heavy maintenance facility |

0.2 |

|

Additional rolling stock |

4.1 |

|

Total Phase I Costs |

$77.3 |

|

HSRA = High‑Speed Rail Authority. |

|

Early Interim Services on Completed Construction Segments. Among other proposed changes, the 2018 business plan proposes to initiate early interim services on completed segments of the IOS in advance of its full construction. Specifically, the HSRA proposes prioritizing completion of the ICS, its extension into Bakersfield, and certain enhancements along the existing Caltrain corridor from San Francisco to Gilroy in order to support interim rail services in those areas as early as 2027. The plan suggests that the completed segments could host enhanced Caltrain and Amtrak services or even abbreviated high‑speed rail operations while construction of the outstanding segments—the Pacheco Pass tunnels and Central Valley Wye—continues. In the 2018 business plan, HSRA reported that it had retained an Early Train Operator (ETO) to conduct an analysis of various potential rail services that could utilize completed portions of the high‑speed rail alignment to inform its March 2019 project update report.

California State Auditor’s Report

In November 2018, the California State Auditor released an audit of the high‑speed rail project. Among other findings, the audit found that the project experienced significant cost overruns as a result of its decision to move forward before it completed critical tasks such as purchasing land and obtaining agreements with external stakeholders. The audit also determined that the risk of additional cost increases is high, and that HSRA will have limited ability to mitigate future cost increases because it has now exhausted all feasible options to use existing infrastructure as part of the system. Additionally, the audit noted that HSRA could be required to repay federal grant funds if it fails to speed up construction sufficiently to complete the ICS by December 2022.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

Project Faces a Significant Funding Gap. The HSRA estimates that the amount of funding available to support the project will fall substantially short of the level needed to complete Phase I of the project. Specifically, as mentioned previously, the 2018 business plan estimates the cost of completing construction of Phase I at $77.3 billion. However, as shown in Figure 7, HSRA also estimates that under current law it will have access to between $19.1 billion and $22.4 billion through 2030, leaving a funding gap of between $54.9 billion and $58.2 billion. Under HSRA’s assumptions, this funding gap could be somewhat smaller—between $49.1 billion and $56.8 billion—if HSRA is able to borrow against its current allocation of 25 percent of cap‑and‑trade revenues through 2050. However, this would require the Legislature to take certain actions, such as extending the cap‑and‑trade program through 2050 and guaranteeing HSRA access to at least a certain amount of funding annually from cap‑and‑trade or other sources to repay investors. (The cap‑and‑trade program is currently authorized through 2030.) We also note that the funding gap would be about $900 million larger if the federal government ultimately terminates the FY10 grant, as discussed above. At this time, HSRA has not specifically identified how the above funding shortfall would be met. Thus, there is significant risk that the state would have to cover the large majority of any funding gap—likely from the General Fund. As we indicated in our review of the June 2018 business plan, it is crucial for the high‑speed rail project to have a complete and viable funding plan in order for the project to proceed.

Figure 7

HSRA’s Estimated Costs and Funding Sources for Construction of Phase I

(In Billions)

|

Amount |

|

|

Estimated Phase I Costs |

$77.3 |

|

Estimated Available Funding |

|

|

Federal funds |

|

|

ARRA |

$2.6 |

|

FY10 |

0.9 |

|

Subtotal |

($3.5 ) |

|

State Funds |

|

|

Proposition 1A |

$7.5 |

|

Cap‑and‑trade received through December 2017 |

1.7 |

|

Future cap‑and‑trade without financinga |

6.5 ‑ 9.8 |

|

Subtotal |

($15.6 ‑ $18.9) |

|

Total Funding Available |

$19.1 ‑ $22.4 |

|

Funding Gap |

$58.2 ‑ $54.9 |

|

aHSRA’s estimate of its share of cap‑and‑trade revenues through 2030 without financing. HSRA estimates borrowing against cap‑and‑trade revenues through 2050 could provide between $7.9 billion and $15.6 billion. ARRA = American Recovery and Reinvestment Act; FY10 = 2010 High‑Speed Intercity Passenger Rail grant; and HSRA = High‑Speed Rail Authority. |

|

Additionally, as we have also previously noted, given the significant scope of the high‑speed rail project, the cost of the project is subject to substantial uncertainty and could increase further. This is because several factors that are not yet known (such as final design decisions, procurements, and construction delays) could potentially affect the actual cost. We note that the project has experienced substantial cost increases already, and the risks of cost increases in the future could be greater because the most complex portions have yet to be completed and, as noted by the State Auditor, HSRA may have limited ability to mitigate any future cost increases.

Peer Review Group Urged Action to Address Funding Gap and Identified Project Alternatives. The Legislature established a Peer Review Group, comprised of transportation and rail experts, to help oversee the project through independent assessments of HSRA’s business plans and designs. In its response to the 2018 business plan, the Peer Review Group noted the project’s continuing and growing funding gap. It urged the Legislature to focus on the question of whether and how the project should continue. It further suggested that, if the project is to continue, the Legislature should consider how adequate and reliable funding can be provided. Finally, as described in the nearby box, the Peer Review Group identified a few possible alternatives for the Legislature to consider in regards to the future of the high‑speed rail project, including continuing with the completion of Phase I as planned or terminating the project early. The choice of which alternative to pursue could have very significant fiscal implications for the state.

Project Alternatives Identified by the Peer Review Group

The Peer Review Group identified four main alternatives for the high‑speed rail project. We summarize these alternatives below:

1. End the Project as Soon as Possible. End the project as soon as practicable, ceasing construction and environmental reviews, settling outstanding contracts, and retaining or selling the acquired right‑of‑way.

2. Complete ICS as a Useable Segment. Complete the initial construction segment (ICS) between Madera and Shafter and provide connections to the existing San Joaquins passenger rail service. Also, complete all outstanding environmental reviews for Phase I to comply with federal grant agreement requirements.

3. Complete Usable Segment and Certain Other Activities. Complete the ICS as a useable segment as envisioned in Alternative #2 as well as certain other activities—such as the upgrade of the Caltrain corridor between San Jose and Gilroy and an extension of the ICS into Bakersfield—consistent with the implementation of early interim services proposed in the 2018 business plan.

4. Complete Phase I. Complete Phase I from San Francisco to Anaheim.

Governor Has Signaled Shift in Approach to Project. In his February 2019 State of the State address, the Governor stated that the high‑speed rail project as planned would cost too much and take too long, and indicated that there is not a path to complete Phase I. Accordingly, he expressed support for completing the construction of the link between Merced to Bakersfield, the bookend projects, and the environmental work for Phase I. Beyond that, at this point, the specifics of the Governor’s plan are uncertain. For example, it is unclear whether the Governor’s approach would result in postponing—or effectively terminating—the remaining portions of the project. Additionally, the details of the Merced to Bakersfield segment are also unclear. Most notably, it is not clear whether the segment would carry high‑speed trains or whether it would instead host express service for the existing San Joaquin passenger rail line. The administration has indicated that additional information on the Governor’s plan may be available in forthcoming documents, such as the March 2019 project update report.

Governor’s Plan Presents Key Opportunity to Consider Project in Context of Legislative Priorities. The Governor’s revised approach to the high‑speed rail project provides an important opportunity for the Legislature to consider how the project aligns with its policy and fiscal priorities. Given the significant funding gap facing the project, it is a good opportunity for the Legislature to evaluate if it would like to continue to move forward with Phase I of the project. If so, the Legislature will want to consider how to address the current funding gap. If not, the Legislature will want to consider its preferred approach to modifying the project, which could involve adopting the Governor’s proposed course of action, one of the alternatives identified by the Peer Review Group, or another available alternative. As it evaluates the various available options, the Legislature will want to weigh the alternatives’ costs and risks against their anticipated mobility benefits. The Legislature’s decisions could be informed, in part, by the additional information that is anticipated to be provided by the administration as part of the March 2019 project update report, including additional details on the Governor’s proposal as well as information from the ETO on anticipated ridership.

Regardless of the approach the Legislature would like to take on the project, there are significant benefits to the Legislature providing clear direction soon. This is because, if the state is going to move forward with the project as currently planned, it would be beneficial to HSRA to have certainty regarding the Legislature’s commitment to completing the project and ensuring its full funding. Alternatively, if the state is ultimately going to scale down the project, the longer the state waits to make this decision, the more likely the state will incur unnecessary costs, such as from acquiring properties that are not needed.