LAO Contacts

April 10, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

Reorganization of the

Division of Juvenile Justice

- Introduction

- Background

- Governor’s Proposal

- Governor’s Proposal Raises Several Key Questions

- Conclusion

Summary

As part of his budget plan for 2019‑20, the Governor proposes removing the Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) and making it a separate department under the Health and Human Services (HHS) Agency. According to the Governor, this reorganization would improve the delivery of services youth need in order to be successful when they are released into the community. While the administration has not provided any additional details about the proposal at this time, it intends to introduce budget trailer legislation related to the reorganization as part of the 2019‑20 budget process.

As the Governor develops his proposed reorganization of DJJ and provides additional detail going forward, it will be important for the Legislature to consider several key questions and weigh the relative trade‑offs of such a change, including whether the change would achieve the benefits specified in statute related to executive reorganizations (such as reduced expenditures and increased efficiency). In order to assist the Legislature, we identify several key questions that merit legislative consideration. These questions include:

- Does DJJ Need to Be Reorganized to Improve Rehabilitation? Currently, it is unclear what specific barriers to rehabilitation currently exist, what specific outcome target the administration is seeking to achieve, and how DJJ is currently performing.

- What Are Potential Benefits of the Proposed Reorganization? The reorganization could potentially result in certain benefits, such as improved rehabilitation and reduced costs for the state. However, the Governor has not provided specific information on the extent to which the reorganization would accomplish these benefits or why they could not be pursued with DJJ’s current organizational structure.

- What Are Potential Consequences of the Proposed Reorganization? The reorganization may not result in improved outcomes, could increase costs, and could result in unintended consequences such as complicating coordination with CDCR.

- Are There Alternative Organizational Options Available? The Legislature will want to consider what other options are available to adjust the organizational structure of the state’s juvenile justice system, including trends in how other states have organized their juvenile justice systems.

- Should the Reorganization of DJJ Be Done Through Budget Trailer Legislation? The administration has not provided a rationale why the proposed reorganization should be done with budget trailer legislation rather than going through the executive branch reorganization process established in statute.

Introduction

The DJJ within CDCR is responsible for housing juvenile offenders committed to state facilities. As part of his budget plan for 2019‑20, the Governor proposes removing DJJ from CDCR and making it a separate department under HHS Agency. According to the Governor, this reorganization would improve the delivery of services youth need in order to be successful when they are released into the community. At the time of this analysis, the administration had not provided any additional details about the proposal and the Governor’s budget for 2019‑20 does not include any adjustments to reflect the proposed reorganization. However, the administration reports that it intends to introduce budget trailer legislation related to the reorganization as part of the 2019‑20 budget process.

In this report, we (1) provide an overview of California’s juvenile justice system including DJJ and (2) highlight several key questions raised by the Governor’s proposal for the Legislature to consider as the administration provides more detailed information on the proposal in the coming months.

Background

Overview of California’s Juvenile Justice System

When a youth is arrested by a local law enforcement agency in California, there are various outcomes that can occur depending on the circumstances of the alleged offense and the criminal history of the youth. For example, arresting officers could choose to turn youths over to their guardians or refer them to county probation departments, which are primarily responsible for youth in the criminal justice system. (Probation departments also receive referrals from non‑law enforcement sources—such as schools and parents.) The probation department generally has the discretion to refer the case to juvenile court, place the juvenile into a voluntary diversion program (such as community‑based programs designed to modify behaviors while redirecting youth away from formal involvement with the criminal justice system), or take other actions. If a probation department chooses to refer the case to juvenile court, the youth will receive a court date. Depending on the circumstances of the case, the juvenile court judge could take several possible actions including placing the youth under county or state supervision or—in certain circumstances—transferring the case to adult court.

Juvenile Court Youth

All youths who are accused of a crime that occurred before they turn 18 years of age and are required to appear in court start in juvenile courts. Juvenile court proceedings are different than proceedings in adult court. For example, if the court determines the youth committed the crime he or she is accused of, the juvenile court judge does not sentence a youth to a set term in prison or jail. Instead, the judge declares the youth a “ward of the court” and determines the appropriate placement based on statute, input from defense and prosecution, and factors such as the youth’s offense and criminal history. The youth then remains in the placement for a period of time based on various factors, such as program length, the youth’s age, or a determination that the youth is ready for reentry into the community.

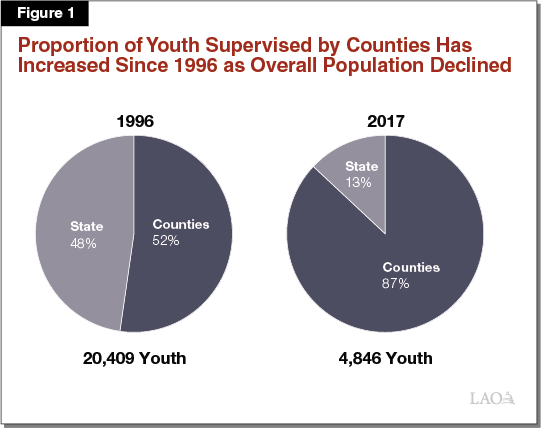

Counties Responsible for Most Juvenile Court Youth. Counties are generally responsible for youth placed by juvenile courts. These youth are typically allowed to remain with their families with some level of supervision from county probation departments. However, some are placed elsewhere, such as in county‑run juvenile halls or camps. Due to several pieces of legislation enacted over the years that increased county‑level responsibility for youth offenders, the portion of youth supervised by counties has increased significantly, as shown in Figure 1. (We provide an overview of major policy changes that contributed to this shift in the nearby box). We note that the overall population of youth involved in the criminal justice system declined dramatically over these years due to a significant decrease in the juvenile arrest rate. There is no consensus among researchers as to why juvenile arrest rates have declined. Accordingly, while counties are responsible for a greater portion of youth, the size of the populations they are responsible for has declined.

Various Legislation Increased Role of Counties in Juvenile Justice System

Over the last two decades, the Legislature has taken steps to shift key responsibilities for managing youth offenders to the counties.

Increased Flat Fee and Established Sliding Scale Fee—Chapter 6 of 1996 (SB 681, Hurtt). Prior to Chapter 6, the state charged counties a flat monthly fee of $25 for each ward housed in state facilities. Chapter 6 required counties to begin paying a sliding scale fee based on the offense committed by the ward. The scale was designed to incentivize counties to keep low‑level offenders at the county level by requiring counties to pay more to house less serious offenders with the state. Counties would pay a flat fee of $150 per month for the most serious offenders. For wards adjudicated for less serious offenses, counties would pay a higher rate of 50 percent, 75 percent, or 100 percent of the state’s institutional cost for housing the ward—with the percentage increasing as the committing offenses decreased in severity. While the institutional costs varied over time, the fees assessed through the sliding scale were generally several thousand dollars per year. During the ten years following the implementation of the sliding scale fee, the average daily juvenile population in state facilities declined by about 80 percent while the population in county facilities remained relatively constant. This increased the share of juveniles supervised by counties, suggesting that the sliding scale could have been effective at incentivizing counties to keep low level offenders at the county level. (We note that the sliding scale became less relevant after the policy changes described below and was replaced by a flat fee in 2012.)

Limited Admission to State Juvenile Facilities—Chapter 175 of 2007 (SB 81, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review). Senate Bill 81 restricted the type of wards who could be housed in the Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) to only those who committed certain significant crimes listed in statute (such as murder, robbery, and certain sex offenses)—effectively increasing the responsibility of counties. To help the counties manage these new responsibilities, SB 81 also established the Youthful Offender Block Grant (YOBG), which currently provides about $180 million in state funds annually to counties for costs associated with supervising youth that might otherwise have been placed under state supervision. Senate Bill 81 also provided counties with $100 million in lease‑revenue funding on a one‑time basis to construct or renovate juvenile facilities, which later increased to $300 million.

Realigned Community Supervision to Counties—Chapter 729 of 2010 (AB 1628, Committee on Budget). As part of the 2010‑11 budget package, the Legislature realigned from the state to county probation departments full responsibility for providing community supervision to all wards released from DJJ, as well as housing those wards who violate the terms of their supervision. The Legislature also established the Juvenile Reentry Grant, which currently provides about $10 million annually to counties for these responsibilities. The funds are distributed across counties based on the number of wards supervised in the community or placed in a local juvenile facility due to violating the terms of court‑ordered supervision.

State Responsible for Most Serious Juvenile Court Youth. If a juvenile court judge finds that a youth committed certain significant crimes listed in statute (such as murder, robbery, and certain sex offenses), the judge can place the youth in state juvenile facilities operated by DJJ. Very few youths are placed in DJJ by the juvenile courts. For example, only 224 youths were sent to DJJ by juvenile courts in 2017—less than 1 percent of the youth placed by juvenile courts. As of December 2018, DJJ housed about 623 juvenile court youths.

Adult Court Youth

Some Youth Tried in Adult Court. All youth start in juvenile court but judges can send certain youth to adult court. Unlike juvenile court, individuals tried in adult court can be convicted and sentenced to a jail or prison term. Recent policy changes have placed restrictions on the circumstances in which a youth could be tried as an adult. For example, Proposition 57 (2016) restricted the type of youth who could be tried as adults to only those who commit a felony when they were age 16 or 17 or commit certain significant crimes listed in state law (such as murder, robbery, and certain sex offenses) when they were age 14 or 15. In addition, Chapter 1012 of 2018 (SB 1391, Lara) further restricted the types of youth who can be transferred to adult court to only those who are age 16 or older. (We note that a court recently issued a temporary stay on Chapter 1012 while it determines whether the measure makes an allowable change to Proposition 57.)

Some Adult Court Youth Housed in DJJ. Under state and federal law, youth must generally be kept separate from adult offenders. As a result, youth tried as adults in California are often housed at DJJ until they turn 18. In addition, DJJ recently established the Young Adult Offender pilot program to allow certain youth convicted between age 18 and 21 in adult court to be housed in DJJ if they are able to complete their sentences prior to turning age 25. As of December 2018, DJJ housed 38 individuals who were tried in adult court.

Overview of DJJ

As previously mentioned, DJJ is currently a division within CDCR. The 2018‑19 budget provided a total of $198.5 million (primarily from the General Fund) for DJJ—an average of roughly $300,000 per youth. (The amount includes $20 million in Proposition 98 [1988] funds to support various educational services provided to DJJ wards.) As of December 2018, DJJ housed a total of about 660 wards—both juvenile and adult court youth—in three facilities (two in Stockton and one in Ventura) and one camp (Pine Grove). The youngest individuals were 15 years of age and the average age was about 19 years old. The vast majority of wards were committed for violent offenses such as homicide, robbery, assault, or rape. The administration projects that the average daily DJJ population will increase to 760 wards during 2019‑20, primarily due to the policy changes limiting which youth can be tried in adult court and the Young Adult Offender pilot program discussed above. The 2018‑19 budget authorized a staffing level of 1,035 employees.

Farrell Lawsuit Prompted Significant Changes in DJJ Treatment and Services

In 2003, a lawsuit, Farrell v. Allen, was filed against the state, alleging that it failed to provide adequate care and effective treatment programs to youths housed in DJJ. In 2004, the state entered into a consent decree in the Farrell case and agreed to develop and implement six remedial plans related to safety and welfare, mental health, education, sexual behavior treatment, health care, dental services, and youth with disabilities. The overarching goal of these plans was to move DJJ toward adopting a “rehabilitative model” of care and treatment. This included the implementation of the Integrated Behavioral Treatment Model (IBTM), which is designed to provide a comprehensive approach to assessing and treating youth while also reducing the likelihood of institutional violence and future criminal behavior. We note that adopting the various remedial plans substantially increased per capita costs within DJJ.

In February 2016, the lawsuit was terminated after the court overseeing the case found that DJJ had sufficiently complied with the requirements of the remedial plans. This released DJJ from court oversight and gave it greater flexibility in determining how to house and treat youth. However, we note that DJJ has generally continued the plans implemented under the lawsuit including the IBTM.

State Juvenile Justice Responsibilities Have Been Reorganized Several Times

Prior to DJJ becoming a division of CDCR in 2005, the state’s juvenile justice responsibilities were organized in different ways over the years. The state first established a separate department known as the California Youth Authority (CYA) in 1953. As we discuss below, CYA was subsequently reorganized on several occasions. These reorganizations were pursued through the executive branch reorganization process that is set in statute and intended to achieve various goals, such as reduce expenditures, increase efficiency, and eliminate duplications of effort. (We describe this process in more detail in the nearby box.) The major organizational changes in juvenile justice responsibilities include:

- 1961—Establishment of Youth and Adult Corrections Agency. CYA and the Department of Corrections (CDC) were moved under the jurisdiction of a new Youth and Adult Corrections Agency. This was part of a larger plan to organize various state departments under eight different agencies. The intent was to modernize and streamline the administration to establish clearer lines of responsibility and improve executive control over the various segments of the executive branch. However, the Governor stated at the time that there was no intent to make changes to the internal operations of the departments as part of these reorganizations.

- 1969—Juvenile Justice Moved Under Human Relations Agency. CYA and CDC—along with ten other state departments—were moved under the Human Relations Agency (a predecessor to the current HHS Agency). The reorganization was intended to eliminate duplication and improve collaboration. The administration’s rationale for moving CYA and CDC into the Human Relations Agency was that the departments shared the agency’s goal of helping individuals achieve self‑sufficiency.

- 1980—Establishment of Youth and Adult Correctional Agency. CYA and CDC were moved under a new Youth and Adult Correctional Agency. The administration’s rationale at the time was that this would help provide consistent and coordinated policy regarding institutional needs, programs, and legislation for both adult and juvenile offenders.

- 2005—Establishment of CDCR and DJJ. The Youth and Adult Correctional Agency was reorganized into one department—CDCR. Under this model, CYA became a division—DJJ—within CDCR. The rationale for the reorganization included strengthening the chain of command, increasing the focus on performance assessment and rehabilitation, and improving efficiency by centralizing shared services between the juvenile and adult systems.

Executive Branch Reorganization Process

The Legislature granted the Governor the authority to reorganize functions among executive officers and agencies through the executive branch reorganization process. In establishing this process, the Legislature stated that the Governor should examine the organization of executive branch agencies to determine if changes are necessary to accomplish one or more broad purposes, such as to reduce expenditures, increase efficiency, or eliminate duplications of effort. Below, we describe the steps required in the reorganization process.

- Before initiating the reorganization process, the Governor must give a copy of the reorganization plan to Legislative Counsel for statutory drafting so that it reflects the form and language suitable for enactment in statute and to ensure that the plan clearly and specifically expresses its nature and purpose.

- At least 30 days before submitting a reorganization plan to the Legislature, the Governor must submit the plan to the Little Hoover Commission—an independent state oversight agency tasked with reviewing and making recommendations to the Governor and Legislature on state operations and any proposed government reorganization plan.

- Once the Governor submits the plan to the Legislature, (1) the Little Hoover Commission has 30 days to issue a report reviewing the plan and (2) the Legislature has 60 days to consider the proposal. Upon receipt, the plan is referred to policy committees of each house. The committees study and report on the plan no later than ten days prior to the end of 60‑day period. Either house can reject the proposal by majority vote—but not until its policy committee has issued a report or the report’s deadline has passed.

- If neither house rejects the reorganization plan during the 60‑day period, it goes into effect on the 61st day.

Governor’s Proposal

As part of his budget plan for 2019‑20, the Governor has proposed removing DJJ from CDCR and making it a separate department under the HHS Agency. According to the Governor, this reorganization is intended to improve the delivery of services youth need in order to be successful when they are released into the community. The Secretary of the HHS Agency has about 360 employees and an annual budget of about $470 million. The agency oversees 12 departments and 4 offices with a total of 30,000 employees.

At the time of this analysis, the administration had not provided any additional details about the proposal and the Governor’s budget for 2019‑20 does not include any adjustments to reflect the proposed reorganization. The administration intends to introduce budget trailer legislation related to the reorganization as part of the 2019‑20 budget process rather than going through the executive branch reorganization process. (We note that the Governor’s budget also proposes to create a new mentorship program to increase the number of former DJJ wards who receive honorable discharge, which we discuss in our recent report The 2019‑20 Budget: Analysis of Governor’s Criminal Justice Proposals.)

Governor’s Proposal Raises Several Key Questions

As the Governor develops his proposed reorganization of DJJ and provides additional detail going forward, it will be important for the Legislature to consider several key questions and weigh the relative trade‑offs of such a change, including whether the change would achieve the benefits specified in statute related to executive reorganizations (such as reduced expenditures, increased efficiency, and elimination of duplication of effort). In order to assist the Legislature, we identify several key questions that merit legislative consideration. These questions are summarized in Figure 2 and discussed in more detail below.

Figure 2

Key Questions for Legislative Consideration

|

|

|

|

|

Does DJJ Need to Be Reorganized to Improve Rehabilitation?

When assessing the merits of the Governor’s proposal, the Legislature should consider whether the proposed reorganization of DJJ is necessary to accomplish its stated goal of enabling the state to better provide youth offenders with the services they need to be successful when they are released from state supervision. As we discuss below, it is unclear what specific barriers to rehabilitation currently exist and what specific outcome target the administration is seeking to achieve.

Barriers to Rehabilitation Unclear. At the time of this analysis, the administration had not provided any information identifying the specific barriers that it believes prevent DJJ from ensuring that youth offenders are successful upon release to the community. Moreover, the administration has not provided any information on how the current organizational structure of DJJ is related to these barriers. As such, it is not clear whether the Governor’s proposed reorganization of DJJ would actually achieve its intended goal and whether it is the most efficient and effective option for doing so.

Intended Outcome Target Not Specified. In addition, the administration has not identified a specific target or outcome measure that the state should achieve regarding its juvenile justice system. Without such a specific target, it is not clear what level of improvement (if any) is necessary. We note that one of the primary ways to measure successful reentry to the community is recidivism—the number of individuals who reoffend after release. DJJ currently measures recidivism as the percentage of youth who are convicted of a new offense within three years of their release from state supervision. DJJ’s most recent outcome evaluation report identifies a recidivism rate of 54 percent for youth released from its facilities in 2011‑12.

While reducing recidivism could be a reasonable goal for the administration, it is not immediately clear what an appropriate target for the recidivism rate should be. For example, while one potential target could be based on the recidivism rates of other juvenile justice systems (such as in other states), we find that such a target is potentially problematic for a couple reasons. First, DJJ has a specific role of only housing youth who have committed certain significant offenses and/or were convicted in adult court. Accordingly, comparing DJJ’s recidivism rate to other juvenile justice systems that house a wider range of youth would not be a fair comparison. Second, other systems may measure recidivism differently than DJJ. For example, some systems use definitions of recidivism that are based on reoffending within a different length of time than the three years measured by DJJ. In addition, other systems may base their recidivism rate on different outcomes than DJJ, such as counting youth who are rearrested but not convicted.

Effects of Recent Efforts to Improve Rehabilitation Unclear. We also note that there is limited data available on DJJ’s recidivism rate. As indicated above, more than half of the youth released from DJJ facilities in 2011‑12 were convicted of new crimes within three years. However, this cohort was released roughly four years before the Farrell case was terminated in February 2016, when the court found DJJ had made sufficient progress toward improving its approach to rehabilitation. Accordingly, these youth would not have benefited from any improvements in DJJ’s rehabilitative programs that occurred in those four years. At the time of this analysis, DJJ had not released recidivism data for youth released more recently. Thus, the actual effects the changes made in response to the Farrell case have had on recidivism remain unclear.

What Are Potential Benefits of the Proposed Reorganization?

While the need for the Governor’s proposed reorganization of DJJ remains unclear, we find that it could potentially result in certain benefits, such as improved rehabilitation. We discuss these potential benefits below.

Potentially Greater Coordination of DJJ’s Goals. The purpose of DJJ as established in statute is to improve public safety through education, treatment, and rehabilitative services provided to youth. While the other divisions of CDCR share the goals of rehabilitation, adult sentences are also intended to serve as punishment. Accordingly, it is possible that the adult system’s goal of punishment could influence the way CDCR operates DJJ. In turn, this could potentially limit the effectiveness of DJJ programs. However, the administration has not provided information that this is the case.

In contrast, several of the departments within the HHS Agency share DJJ’s goals of rehabilitation without including a goal of punishment. For example, individuals who have been convicted of a violent offense connected to their severe mental disorder can be committed to the Department of State Hospitals (DSH) as Mentally Disordered Offenders (MDOs) after they complete their prison terms if they have been found to pose a danger to the public. DSH provides treatment to MDOs until it is determined that they are no longer a threat to public safety. DSH also provides treatment to other individuals involved in the criminal justice system. In addition, the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) and the Department of Social Service (DSS) (in collaboration with their county‑level counterparts) are involved in the provision of services to youth in foster care who have somewhat similar needs to youth involved in the juvenile justice system. Specifically, both populations have higher rates of diagnosed mental health and substance use disorders than the broader youth population. As such, the HHS Agency could be well positioned to oversee the delivery and improvement of services for the DJJ population.

Possible Opportunities for Early Intervention. It is possible that the HHS Agency would be better positioned than CDCR to pursue early intervention strategies with at‑risk youth. This is because many youth who end up in the juvenile justice system have prior contact with services provided by HHS departments or their county‑level counterparts. For example, research shows that a history of interactions with a child welfare agency is a significant risk factor for ending up in the juvenile justice system. Specifically, a 2015 study found that over 80 percent of probation youth in Los Angeles County had been referred to child protective services at least once for maltreatment while about 40 percent had a substantiated report of maltreatment. We also note that DSS provides some oversight and technical assistance to county‑level child protective services agencies—including assistance facilitating the establishment of new programs. In theory, this could include facilitating the development of early intervention programs. That being said, the administration has not provided any specific information on the manner or extent to which the proposed reorganization would include early intervention efforts or why such efforts could not be pursued with DJJ’s current organizational structure.

Possible Improvements in Reentry Service Coordination. The Governor’s proposal could also potentially improve coordination of services for youth released from DJJ to county probation. While CDCR coordinates with county probation departments who typically supervise youth released from DJJ facilities, HHS departments have more involvement with the county agencies that provide services that may benefit youth released from DJJ. For example, DHCS is responsible for providing oversight and technical assistance to counties in their provision of mental health and substance use disorder treatment services.

In addition, the HHS Agency is currently taking steps to improve coordination between departments to improve services for youth. For example, DHCS and DSS are currently working on ways to improve access to mental health services for youth in the foster care system. This work could be expanded to increase access for youth released from DJJ. However, the administration has not provided at this time specific information on the manner or extent to which the proposed reorganization would result in such benefits or why they could not be accomplished within DJJ’s current organizational structure.

Potential Reduction in Costs if Rehabilitative Programs Improve. To the extent that the proposed reorganization results in improved rehabilitative services, it would not only improve the lives of DJJ youth and increase public safety, but it would also have several direct and indirect fiscal benefits for the state. Direct fiscal benefits could include reduced incarceration costs as well as reduced crime victim assistance costs. Indirect benefits could include reduced costs for public assistance if improvements to rehabilitative programs such as career and technical training resulted in an increase in employment, thereby reducing the level of public assistance needed. These direct and indirect benefits, if accomplished, could potentially reduce state expenditures—one of the purposes for reorganization listed in statute.

What Are Potential Consequences of the Proposed Reorganization?

In addition to weighing the potential benefits of the proposed reorganization, the Legislature will want to consider its potential consequences. These include the possibility that the reorganization may not result in improved outcomes and could increase state costs. Given the complexities of the issues involved in a government reorganization, the proposal could also result in unintended consequences that merit consideration. In particular, as we discuss below, the proposed reorganization of DJJ could complicate coordination with CDCR and potentially disrupt existing services for youth offenders.

May Not Result in Improved Outcomes. While the Governor’s proposal would elevate DJJ to departmental status, it is unclear what the implications would be in terms of the level of support and oversight provided by the HHS Agency relative to the current support and oversight provided by CDCR. For example, it is possible that the HHS Agency might take a more active role in monitoring the implementation of rehabilitative programming for youth offenders. On the other hand, because DJJ would be one of several departments reporting to the HHS Agency, it could receive less attention than it currently receives under CDCR. Without a detailed proposal from the administration, it is unclear at this time whether the proposed reorganization would translate into any actual impact on youth or if it would simply shift responsibilities at the top of the organizational structure. Unless the reorganization leads to changes in the day‑to‑day operations of facilities or improved coordination with other state and county service providers, it is unlikely that it would improve outcomes for youth.

Potential Increased Costs. As a division within a department, DJJ currently depends on CDCR for certain administrative services, such as those related to its budget, officer training, and population projections. Becoming a separate department could require DJJ to now be fully responsible and directly perform some of these functions. For example, DJJ would likely need to establish its own offices or divisions to oversee its budget and develop population projections, which would likely require additional staff and funding that could not simply be redirected from CDCR. This is because some of the CDCR staff that currently provide these services for DJJ also provide service to other divisions within the department and utilize resources such as computers, software, and office space that would likely still be needed by CDCR. Thus, recreating these divisions would result in a duplication of effort. We also note that the rationale for the 2005 reorganization that consolidated the Youth and Adult Corrections Agency into CDCR included centralizing the policy and administrative functions with the intent of eliminating duplications of effort.

Potential Challenges in Coordinating With CDCR. Currently, there are multiple circumstances in which offenders move between DJJ and CDCR custody. For example, some youth who are tried as adults begin their sentence in DJJ but are moved to a CDCR adult prison after they turn 18. In addition, some young adults are transferred to DJJ after being sentenced to state prison, such as those who are part of the Young Adult Offender pilot discussed earlier. Moreover, youth who are convicted in adult court but serve their terms in DJJ are often released to the supervision of CDCR’s adult parole division. If DJJ becomes a separate department, it may be more difficult to coordinate these transfers leading to delays, issues with information sharing, or other complications.

Moving individuals between CDCR and another state department has caused challenges in the past. Specifically, CDCR used to refer many inmates with serious mental health conditions to DSH for treatment. However, the resulting interdepartmental transfers contributed to delays in providing the treatment. Accordingly, in 2017, a federal court issued an order stating that CDCR needed to eliminate delays in transferring patients to the appropriate level of mental health care. This was part of a ongoing case now referred to as Coleman v. Newsom.

Potential Disruption in Services. The complexity of most government reorganizations—such as the one proposed by the Governor—can often result in an unintended disruption in services. This is primarily because all of the necessary statutory changes can sometimes be difficult to immediately identify or implement correctly. For example, the California Prison Industry Authority (CalPIA) currently operates a number of vocational programs within DJJ facilities. However, CalPIA may not have the statutory authority to continue operating these programs if DJJ was separated from CDCR absent any statutory changes.

We note that prior government reorganizations have sometimes caused an unintended disruption in services. For example, when supervision of former DJJ wards in the community was shifted from DJJ to the counties in 2010, the honorable discharge process—in which the Board of Juvenile Hearings recognizes youths for their efforts at rehabilitating themselves—unintentionally stopped. This was because the board no longer had jurisdiction over the youth. The honorable discharge process for former wards of DJJ was eventually re‑established seven years later through legislation.

Are There Alternative Organizational Options Available?

In evaluating the Governor’s proposal, the Legislature will also want to consider other options that are available to adjust the organizational structure of the state’s juvenile justice system. For example the Legislature might want to consider trends in how other states have organized their juvenile justice systems and what other ways the Legislature could change California’s juvenile justice system. As we discuss below, the Legislature will want to weigh the relative trade‑offs of each of the alternative structures.

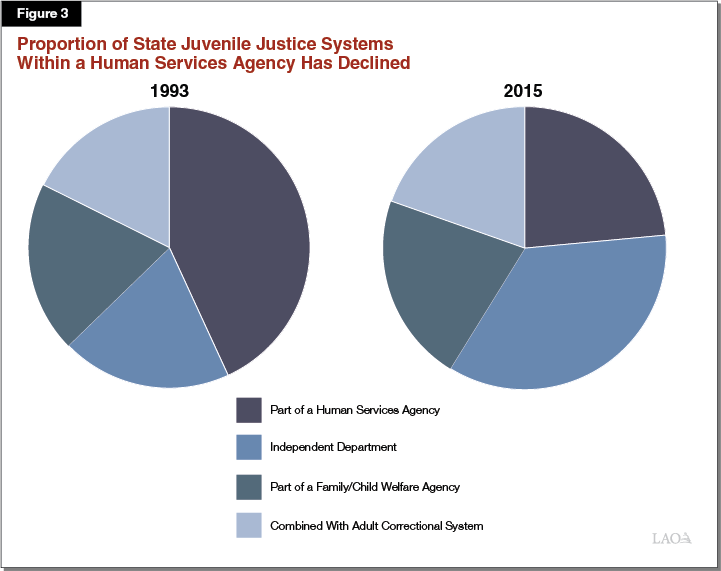

Organization of Juvenile Justice in Other States Varies. The organization of juvenile justice systems vary widely across states. However, they generally fall into one of four categories. Specifically, state‑level juvenile justice systems are typically (1) independent departments that are not under a larger agency structure, (2) part of a department or agency that includes adult corrections (similar to DJJ’s current structure), (3) part of a broad human services agency (similar to the Governor’s proposal for DJJ reorganization), or (4) part of an agency focused specifically on family or child welfare. Figure 3 shows trends in the organizational structure of state‑level juvenile justice systems between 1993 and 2015. In 1993 the most common structure was for state‑level juvenile justice systems to be part of a human services agency. However, half of the states that had this organizational structure moved away from it by 2005. As of 2015, independent departments are the most common organization structure. A few notable shifts in organizational structures between 1993 and 2015 include the following:

- Colorado shifted its juvenile justice system from being merged with its adult corrections system to being part of a human services agency.

- Kansas, North Carolina, and Wisconsin shifted their juvenile justice systems from being parts of human services agencies to being merged with their adult corrections systems.

- Washington D.C., Florida, Idaho, Kentucky, Nevada, Oklahoma, Oregon, and Vermont all shifted their juvenile justice systems from being parts of human services agencies to being independent departments.

Making DJJ an Independent Department. As noted above, the most common approach among other states is to have their state‑level juvenile justice system be an independent department. As a division of CDCR, the operations of DJJ are subject to the guidance and direction of the department. If it is demonstrated that the current structure inhibits rehabilitation efforts, making DJJ an independent entity could improve them. In addition, this approach could potentially allow the administration and the Legislature to provide greater oversight of DJJ, as they would not have to go through CDCR (as is currently the case) or potentially the HHS Agency (as proposed by the Governor). On the other hand, eliminating the role of an intermediary such as CDCR or the HHS Agency could actually result in DJJ receiving less oversight and support. It could also result in many of the unintended consequences of the Governor’s proposed reorganization, such as increased costs and making it more challenging to coordinate with other divisions of CDCR.

Realignment of DJJ to Counties. As discussed earlier, California has already shifted most juvenile justice responsibilities to the counties. One option for legislative consideration is to realign DJJ’s remaining responsibilities to the counties. Our analysis indicates that such a shift would have several potential benefits compared to the current structure of DJJ. For example, a full realignment of juvenile justice to counties would increase accountability for results by concentrating responsibility for the juvenile justice system in one level of government, as well as strengthen the incentive for counties to prevent youth from becoming serious offenders. In addition, keeping youth at the local level would allow them to be closer to support structures (such as family) and better position probation departments to help youth transition through the system and secure services in the community.

Fully realigning the juvenile justice system to counties would also likely reduce state costs and allow for more efficient use of existing facilities. Currently, DJJ’s facilities are at about 40 percent of their total capacity. This has led to significantly high per DJJ capita costs due to the high fixed costs of running the facilities despite the low population levels. Similarly, counties are operating their facilities at about 30 percent of their capacity on average. Accordingly, realignment would allow the state to avoid the large fixed costs of its facilities, and make better use of existing county facilities by placing the existing DJJ population in them.

In addition to reducing overall costs, concentrating resources at the local level would give counties the flexibility to adopt policies and strategies that are aligned with the particular needs of their communities and youth offenders. For example, one county might choose to take actions to reduce gang involvement while another county might focus on vocational training. We note that if the Legislature decides to realign the state’s remaining juvenile justice responsibilities to the counties, it would want to consider (1) a funding structure that incentivizes innovation and efficiency, (2) a plan that ensures a smooth transition, (3) a process to provide state oversight and technical assistance, and (4) policy changes necessary to ensure that the realignment would not result in youth simply being shifted into the adult system. (Please see our report, The 2012‑13 Budget: Completing Juvenile Justice Realignment, for more information regarding the possible realignment of DJJ.)

Maintain Existing Structure but Consider Other Changes. As stated earlier, some of the identified benefits of reorganization could potentially be achieved within the current structure of DJJ. For example, policies could be developed to improve coordination between DJJ, counties, and other state departments. In addition, the Legislature could take actions to increase third‑party oversight and evaluation of DJJ rehabilitation programs if it is concerned that DJJ needs further improvement in these areas. Between 2006 and 2016, the Special Master in the Farrell case conducted quarterly inspections of DJJ’s operations. Since 2016, however, third‑party oversight has been limited. While the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) provides some oversight, it is generally limited to the division’s response to claims of employee misconduct and use of force and there is minimal oversight of DJJ rehabilitation programs. We note that increasing oversight—either by the OIG or another entity—would likely require additional resources.

We also note that CDCR’s adult prison system has inmate rehabilitation as one of its primary goals. However, in a recent report, the State Auditor found that administrative practices within the adult prison system—such as not placing inmates into appropriate rehabilitative programs and a lack of oversight regarding the effective implementation of such programs—have limited the effectiveness of certain rehabilitative programs at reducing recidivism. To the extent that the barriers to effective rehabilitation programming impacting the adult prison system are similar to those impacting DJJ’s rehabilitative efforts, the Legislature could consider directly addressing the barriers within CDCR rather than moving DJJ into a separate department. To the extent this approach was successful, it would not only improve outcomes for the roughly 700 youth in DJJ, but also for the 127,000 inmates and 50,000 parolees in the adult system.

Should the Reorganization of DJJ Be Done Through Budget Trailer Legislation?

The administration has not provided a rationale for why this reorganization should be done with budget trailer legislation rather than going through the executive branch reorganization process established in statute. When considering the reorganization plan, the Legislature might also want to consider whether this approach is appropriate. We note that the legislature has raised concerns about using budget trailer legislation for similar purposes in the past. For example, in 2012‑13, the Governor’s proposed budget included three agency reorganization proposals that it intended to pursue through budget trailer legislation. At the time, questions were raised in the Legislature as to whether it would be appropriate to reorganize state agencies without going through the process established in statute. Ultimately, the reorganizations went through the executive branch reorganization process.

The executive reorganization process is not only relatively expedient (it can be completed in 90 days) but also includes a framework designed to increase the likelihood that a reorganization would be effective and smoothly implemented. For example, as part of the process, the Little Hoover Commission conducts an independent analysis to determine the plan’s impact on state operations, which could help identify potential consequences of the reorganization. In addition, the process requires that plans put forward by the Governor must (1) provide for the transfer or disposition of any property or records affected by the reorganization; (2) ensure that any unexpended appropriations are transferred in accordance to the legislative intent for the funds; and (3) list all statutes that would be inconsistent with the reorganization plan and as a result, would be suspended. These requirements would not apply to trailer bill language.

Conclusion

Over the years, the organizational structure of the state’s juvenile justice system has evolved. While the Governor’s proposal to place DJJ under the HHS Agency with the goal of improving the outcomes of youth could have some potential benefits, the administration has provided very little in the way of details at this time about how the reorganization would be implemented and why it is needed. Given the complexity of both the state’s juvenile justice system and the process of reorganizing state government, there should be a well‑defined purpose and plan for carrying out this proposal. As the Governor develops his proposed reorganization of DJJ and provides additional detail going forward, it will be important for the Legislature to consider several key questions (such as whether DJJ needs to be reorganized to remove barriers to rehabilitation) and weigh the relative trade‑offs of such a change. Moreover, the Legislature could consider alternative approaches to the Governor’s proposal that could more effectively result in improved outcomes for youth.