LAO Contact

May 9, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

Assessing the Governor’s Primary Care Physician Residency Proposals

Summary

Governor Proposes $73 Million Ongoing General Fund for Two Programs That Support Physician Residents. The programs—one administered by the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) and one administered by the University of California—provide grant funding to support physician residency programs. Both grant programs focus on supporting hospitals and clinics that train physician residents and serve regions with relatively few physicians and/or underserved populations.

Understanding of Shortages and Policy Responses to Them Could Be Improved. While there are documented disparities in the supply of primary care physicians across regions, further analysis is needed as to the underlying causes of these disparities. More analysis also is needed as to whether supporting residency programs is the most cost‑effective policy option for addressing regional disparities. Even if supporting residency programs were found to be the most effective strategy, we believe the state’s two existing programs focus too heavily on supporting existing residency slots. Providing limited‑term funding for the development of new resident programs could be a more effective way to increase the supply of residents. This is because most hospitals rely on federal Medicare subsidies to cover a substantial portion of ongoing resident training costs, and most hospitals have reached their federal funding caps. New programs, by contrast, have a five‑year window to access new federal funding and expand the number of residents they train before reaching their funding cap. The state also can channel grant funding toward hospitals located in shortage areas of the state that do not yet have residency programs. We are also concerned about the inefficiency of the state operating two very similar grant programs. Two programs makes planning and accountability more difficult, increases administrative costs, and reduces the share of funding allocated directly to residency programs.

Recommend Providing Limited‑Term Funding and Considering Programmatic Improvements. To address these concerns, we recommend the Legislature continue to provide limited‑term funding (extending three to five years) for residency programs rather than making the funding ongoing, as proposed by the Governor. Under a limited‑term approach, the Legislature can periodically reassess workforce issues and realign its policy responses accordingly. We also recommend the Legislature consolidate grant funding into one program to better target and maximize state funding. Furthermore, we recommend the Legislature prioritize any limited‑term funding for the development of new residency programs that could qualify for federal Medicare subsides to help cover ongoing costs. To this end, we recommend the Legislature direct OSHPD to study which hospitals would qualify to receive these subsidies. The Legislature could prioritize any remaining funding for existing residency programs that add slots and have documented financial need.

Introduction

To obtain a license to practice medicine, California law requires all medical school graduates to complete three years of postgraduate training. Most physician‑trainees fulfill this requirement by completing a residency program. The state currently funds two initiatives to support residency programs for primary care physicians. The first initiative is named after its legislative authors, Song‑Brown, and is administered by the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD). The second initiative is authorized by Proposition 56 and is administered by the University of California (UC). The Governor proposes making certain limited‑term funding for these initiatives ongoing. In this brief, we provide background on residency programs, describe the Governor’s two associated budget proposals, assess those proposals, and make associated recommendations.

Background

In this section, we first provide some basic information about residency training programs. We then provide an overview of federal Medicare and other subsidized health programs, which provide the vast majority of public funding for residency programs in California. We next describe the state’s Song‑Brown and UC‑administered residency grant programs.

Overview of Residency Programs

Residency Typically Is the Final Training Step to Becoming a Doctor. As the final step in their medical training, residents provide supervised clinical care (traditionally in a hospital setting) and participate in various educational activities. In 2018‑19, an estimated 116,500 physician residents trained in the United States, of which 10,350 (8.9 percent) trained in California. Though California has the largest number of physician residents among the states, it ranks 31st for the number of physician residents per population. Health care providers operate residency programs, often in affiliation with a medical school.

Residents Choose to Pursue Primary Care or Specialty Care. All residency programs train students to practice within a specific area of medicine. Medical areas can be thought of comprising two broad categories: primary care and specialty care. Within primary care, residents can focus on family medicine (patients of all ages), internal medicine (adult health), pediatrics (child health), and obstetrics/gynecology (female reproductive health). Within specialty care, residents can focus on one of more than 20 specialty areas, including emergency care, surgery, or psychiatry. Most primary care residency programs are three years long. Obstetrics/gynecology and most specialty programs last longer than three years. Though not required by state law, most residents seek sector‑recognized certification in their medical area upon completing their respective programs. Nearly 80 percent of active physicians (primary and specialty care) in the United States are certified.

Federal Funding

Medicare Is Primary Source of Public Funding for Residency Programs. Medicare is a federal program that provides health care coverage for adults ages 65 and older. In acknowledgement of the medical staff needed to serve this population, Medicare provides payments to hospitals to cover a portion of their resident training costs. Hospitals’ residency payments are largely determined by two key factors. First, hospitals generally qualify for payments by providing inpatient services to Medicare patients, with a hospital’s payment increasing as the share of its inpatient hours devoted to Medicare patients increases. This factor is intended to recognize Medicare’s share of the cost to train residents, with private payers expected to cover the remaining portion of training costs. Second, hospitals’ Medicare’s payments generally increases with the number of residents they train until they reach a cap. For most residency programs, the subsidy is capped at the number of residents they trained in 1997. This cap was established during a time when policymakers believed the nation had a surplus of physicians. In 2016, Medicare provided a total of $12 billion in residency payments to hospitals, of which $744 million (6 percent) went to California hospitals.

Medi‑Cal Also Traditionally Has Helped Fund Residency Programs but the Rules Have Been Changing. Medicaid is a federal program that provides health care coverage for low‑income individuals. In California, the program is called Medi‑Cal. Prior to 2005, Medi‑Cal had an explicit subsidy for residency costs at public hospitals that was similar in design to the Medicare payments. As part of numerous changes to the way California allocates Medi‑Cal funds to public hospitals, in 2005 the state consolidated these payments and removed the requirement that they be spent on residency programs, instead allowing the payments to cover any medical cost. In conversations with our office, the Department of Health Care Services indicated that it is not able to estimate how much of these consolidated (or supplemental) payments hospitals currently spend on residency programs. Beginning in 2018‑19, the state intends to enter into an agreement with the federal Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services that would increase the amount of federal supplemental Medicaid payments for residency programs. The administration estimates the agreement will result in an estimated $230 million annually in additional federal funding for public hospitals with residency programs in California. Whether these hospitals will use the additional funds to sustain or expand their existing residency programs is not yet known.

Smaller Federal Grant Programs Have Helped Support Residency Programs in Certain High‑Priority Areas. In addition to Medicare and Medicaid, the federal government over the years has developed other programs intended to support specific residency programs that may not qualify for a subsidy from Medicare. For example, in recent years the federal Health Resources and Services Administration has provided grants to certain outpatient health clinics and children’s hospitals to help support residency costs. These program grants have been limited term.

Song‑Brown Funding

Song‑Brown Supports Primary Care Residency Programs. Originally established by Chapter 1175 of 1973 (SB 1224, Song), the program was created to address perceived shortages of family physicians by increasing support for residency programs. Since this initial legislation, Song‑Brown has expanded to support residency programs in all four primary care areas (family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, and obstetrics and gynecology) as well as certain advanced nursing practice and physician assistant postgraduate training programs. Song‑Brown is a competitive grant program that covers a portion of the cost to train a residency cohort at an eligible hospital. A 15‑member commission representing medical schools, physician residents, and primary care providers decides how to allocate funds among hospitals. The Governor, the Speaker of the Assembly, and the Chairperson of the Senate Committee on Rules each appoint certain members to the commission.

Grants Targeted for Geographic Areas With Relatively Few Physicians or Underrepresented Populations. To allocate grant funding among hospitals’ residency programs, OHSPD staff assess each application on a point‑based system. The system awards points primarily based on whether the residency program serves areas of the state that OSHPD considers primary care shortage areas. OSHPD determines these areas based on the share of their population living at or below the federal poverty level and their physician‑to‑population ratio. In 2017, OSHPD identified 303 primary care shortage areas, collectively containing 17 million people (45 percent of the state’s population). OSHPD also awards points for (1) the share of residency program graduates who are from underrepresented groups; (2) the share of Medicare, Medi‑Cal, and uninsured patients treated by the sponsoring hospital; and (3) various other factors (such as the share and number of graduates working in primary care ambulatory settings).

Song‑Brown Has Been Funded in Various Ways. Prior to 2008‑09, the program was primarily supported by state General Fund. Then, from 2008‑09 through 2016‑17, the state provided no General Fund for the program, with the program instead supported by a small amount of funding from fees enacted on health facilities. In the latter part of this period—between 2013 and 2016—Song‑Brown also received a one‑time grant totaling $21 million from the California Endowment, a nonprofit organization.

State Recently Resumed General Fund Support for Song‑Brown. The 2017‑18 budget package included $100 million General Fund for Song‑Brown, with the funds spread evenly over three years ($33 million each year through 2019‑20). Figure 1 shows how the state allotted the funding among new and existing residency programs. The bulk of the funds ($73 million) was to support existing residency slots. The remaining funds were for adding slots at existing programs, funding start‑up costs for new programs, funding loan repayment programs, and funding associated state operations. The infusion of state funds was intended to backfill foregone California Endowment funds and increase overall public funding for residency programs. (At the time the 2017‑18 budget was enacted, some decision makers also expected that certain existing slots at outpatient teaching health centers would lose one‑time federal funding. These federal grants, however, have since been extended.)

Figure 1

Legislature Adopted Three‑Year Plan for Song‑Brown Funding

2017‑18 Through 2019‑20, General Fund (In Millions)

|

Annual Funding |

Three‑Year Funding |

|

|

Grants for residency programs |

||

|

Existing slots at existing programsa |

$24 |

$73 |

|

Added slots at existing programs |

3 |

10 |

|

Start‑up costs at new programs |

3 |

10 |

|

Subtotal |

($31) |

($93) |

|

Loan repayments |

— |

$1 |

|

State administration |

$2 |

6 |

|

Totals |

$33 |

$100 |

|

a Includes two types of grants. One grant funds hospital‑based residency programs and the other grant funds residency programs at community‑based outpatient centers. |

||

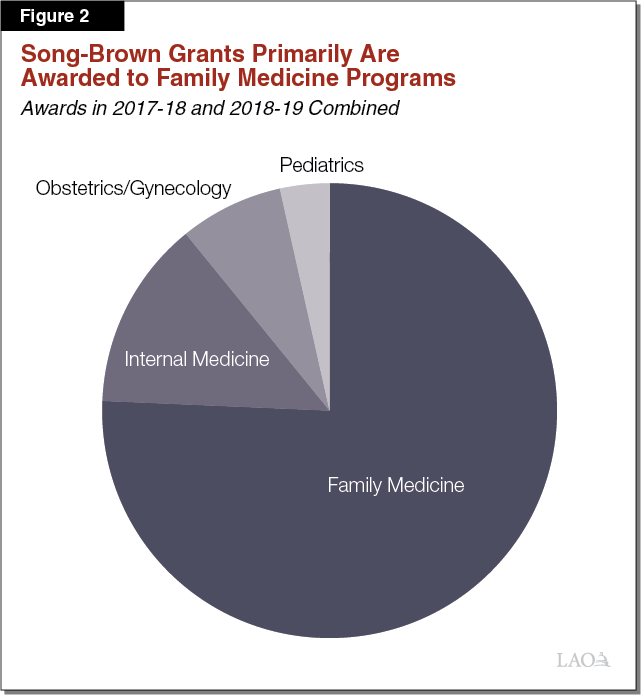

Grants in Recent Years Have Focused on Family Physicians. Across 2017‑18 and 2018‑19, about three‑fourths of grant funding has been awarded to residency programs training family physicians, with the remainder spread across the other primary care areas (Figure 2). About 30 percent of grant funding has been awarded to UC‑sponsored residency programs, with the remaining 70 percent awarded to other hospital‑sponsored residency programs.

Proposition 56 Funding

Proposition 56 Earmarks Some Funding for Residency Programs. Proposition 56 (2016) imposed a tax on tobacco products and designated the associated revenue for several programs. Among these allocations, the measure designates $40 million annually to UC to “sustain, retain, and expand” primary care and emergency care physician residency programs in California. In addition, the measure allows UC to provide funding for specialty care areas where demonstrated statewide and regional shortages exist. While the measure does not formally establish a competitive grant program for the funding, the measure states that all accredited physician residency programs in California shall be eligible to apply for funding.

State’s Approach to Using Proposition 56 Residency Funds Has Changed. Though Proposition 56 states intent to address physician shortages, the measure does not contain a clause prohibiting the additional tobacco revenue from supplanting existing state support for residency programs. (By contrast, the measure prohibits supplanting for many other programs.) In 2017‑18, the state used the new Proposition 56 funds to supplant rather than supplement General Fund that UC stated it had been using for its residency programs. In 2018‑19, the state reversed course, using the Proposition 56 funds to supplement residency programs and providing a one‑time General Fund backfill undoing the 2017‑18 budget action (thereby making UC’s General Fund whole).

One‑Time Program Administered by Nonprofit Entity. To administer the additional residency funds in 2018‑19, UC contracted with a nonprofit organization called Physicians for Health California that is affiliated with the California Medical Association. Physicians for Health California in turn organized a five‑member governing board and a 15‑member advisory council to develop a plan to allocate funding. As Figure 3 shows, the members of the board and council each represent different groups of health care provider associations.

Figure 3

UC Physician Residency Grant Program

Is Overseen by Board and Advisory Council

Associations Participating in Each Board

|

Five‑Member Governing Board |

|

Physicians for a Healthy California |

|

California Medical Association |

|

University of California |

|

California Hospital Association |

|

Service Employees International Union |

|

15‑Member Advisory Council |

|

American Academy of Pediatrics |

|

American College of Emergency Room Physicians |

|

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists |

|

American College of Physicians |

|

California Association of Public Hospitals and Health Systems |

|

California Children’s Hospital Association |

|

California Hospital Association |

|

California Medical Association |

|

California Primary Care Association |

|

California private medical schools |

|

Network of Ethnic Physician Organizations |

|

Osteopathic Physicians of California |

|

Service Employees International Union |

|

University of California |

Grants Focused on All Primary Care Areas. In 2018‑19, the governing board approved a plan to allocate $38 million in grants, with the remaining $2 million earmarked for administrative costs (Figure 4). The grants were allocated to hospitals throughout California. Of the grant funding, the largest share was allocated to family medicine programs, same as the Song‑Brown grants, but each of the three other primary care areas received somewhat higher shares of the Proposition 56 grant funding compared to the Song‑Brown grants. According to UC, the Proposition 56 grant funds supported 156 residents, of which UC indicated 82 were “new” slots and 74 were “existing” slots. (At the time of this analysis, the university was unable to confirm whether funding went only to existing residency programs or if grants were also allocated to new residency programs.)

Figure 4

UC Allocates Funding Among Medical

Areas More Evenly Than Song‑Brown

2018‑19 (In Millions)

|

Funding |

|

|

Grants for residency programs |

|

|

Family medicine |

$9.5 |

|

Emergency medicine |

7.6 |

|

Internal medicine |

7.6 |

|

Pediatrics |

7.6 |

|

Obstetrics/gynecology |

5.7 |

|

Subtotal |

($38.0) |

|

State administration |

$2.0 |

|

Total |

$40.0 |

Governor’s Proposals

Proposes to Make Song‑Brown General Fund Augmentation Ongoing. In The Governor’s Budget Summary, the Governor signals his intent to make $33 million annual General Fund ongoing beginning in 2020‑21 (as the previously enacted budget appropriation extends through 2019‑20).

Proposes to Make UC General Fund Augmentation Ongoing. The Governor proposes providing UC with $40 million ongoing General Fund beginning in 2019‑20 for residency programs. This ongoing funding would enable UC to use its Proposition 56 money to fund grants to California residency programs on an ongoing basis. (In a separate action, the Governor proposes to reduce Proposition 56 funding for residency programs from $40 million to $37 million in 2019‑20. This proposal is further described in our webpost Proposition 56 Revenues: Reductions in Fixed Allocations.)

Assessment

When considering the Governor’s proposals to fund these two residency grant programs on an ongoing basis, the Legislature has many issues to consider. First‑order issues entail understanding whether a primary care physician shortage exists and, if so, its underlying causes and how best to address it. Were state support for residency programs found to be a promising policy response to a physician shortage, the Legislature then faces the issue of how to fund grant programs effectively and efficiently. In this section, we discuss both sets of issues.

Understanding and Addressing Workforce Shortages

Strongest Evidence of Possible Regional Shortages, Though Further Analysis Is Needed. Based on our review of existing workforce analyses, certain regions in the state—the Central Valley, Inland Empire, and Northern California—have lower primary care physician‑to‑population ratios than other areas of the state. The disparities are likely most acute in these regions’ rural communities. While disparities in the supply of primary care providers are well documented, additional analysis is needed to determine how demand for services differs among the regions.

Little Comparative Analysis of Which Policy Options for Addressing Shortages Are Most Effective. Many policy options exist that have the potential to affect the physician pipeline. Potential options include outreach and increasing the number of applicants from rural communities who apply to medical schools, increasing medical school enrollment, or expanding physician residency programs. In addition, the state has funded certain programs, such as loan‑repayment programs, that incentivize physicians to practice medicine in shortage areas after completing their residency. Policy options also include expanding the education pipeline for nurse practitioners and physician assistants, both of whom can provide some primary care services under the supervision of a physician. In our preliminary review of all these options, we could not find evidence indicating which of these policy options is most effective in addressing primary care physician shortages in rural regions.

Experts Debate Extent to Which Physician Residents Are a Net Cost to Hospitals. On the one hand, some experts argue that residency programs can fully cover their costs from clinical revenues generated by the residents providing patient services. Largely in recognition of the net value of these services, residents are paid an annual stipend (on average $56,100 for first‑year residents). On the other hand, some experts argue that hospitals incur residency training costs that are not fully covered by clinical revenues or Medicare subsidies. (Furthermore, health field experts typically point out that certain areas of medicine are more financially lucrative than others, with primary care programs considered to be among the least revenue‑generating areas.) In our preliminary review of the available research on this issue, we could not find conclusive empirical evidence supporting either of these competing theories.

Improving Impact and Coordination

Assisting New Programs May Have Biggest Return on Funding . . . Though existing research provides no clear path forward regarding the most cost‑effective way to address primary care physician shortages in rural areas, the Legislature may want to consider how to make its existing efforts to address these shortages more effective. Though comprising the smallest portion of existing state residency grant funding, the state could refocus its efforts moving forward on developing new primary care residency programs. This approach has a couple of key benefits, First, it accesses more federal funding. As additional hospitals begin training residents, these hospitals would qualify for additional federal Medicare funding to cover their residency costs on an ongoing basis. This approach would be a more effective way to grow residency slots on an ongoing basis than by funding growth at existing residency programs that have already reached their federal Medicare funding caps. In addition, the state could work with hospitals to launch new residency programs in shortage areas that to date have not had such programs. (Though shortage areas already receive priority for state grant funding, not all of these areas have residency programs.)

. . . But Expansion Strategy Has Uncertainty and Risk. The primary uncertainty is that the potential number of hospitals that could host new programs is unknown at this time. According to the Robert Graham Center, a nonprofit organization focused on the health care workforce, there are around 260 hospitals in California that have not received Medicare payments for residency programs since 1996. Experts we spoke with, however, indicated that many of these hospitals likely would not wish to start residency programs. In addition, the federal government can disqualify a new program from receiving Medicare funding if a hospital had historically hosted a residency program. Given these limitations, additional research is needed to determine how many potential new programs could be launched. Some risk also is associated with programs being able to launch successfully, as starting up such programs entails many steps.

Funding Existing Programs May Have a Positive Impact but Could Result in Some Supplanting. While state funding for existing residency programs in some cases could help sustain slots that have relied on limited‑term federal and private funding, new state funds in other cases could supplant existing fund resources. This is because neither of the state’s two grant programs award points based on a residency program’s existing financial resources when allocating funding. Our office was informed of one instance where a program used a Song‑Brown grant to supplant existing funding for its primary care program and used freed‑up funds to create new specialty care programs. In this instance, the Song‑Brown program had the overall effect of growing specialty programs slots instead of primary care slots, contradicting a longstanding goal of the program.

Operating Two Similar Programs Is an Inefficient Way to Fund Residency Programs. As Figure 5 shows, the Song‑Brown and UC Proposition 56 programs have substantial crossover in their missions and governance structures. Both programs focus on primary care physicians, with the main difference that Song‑Brown funds some nursing and loan repayment programs whereas the UC program funds some emergency care and potentially other specialty physician areas. Providing grants through two very similar programs is inefficient for two reasons. First, having two programs fragments efforts to address regional physician shortages—making planning, funding, and monitoring all the more difficult. For example, in 2018‑19, some residency programs received funding from both the Song‑Brown and UC programs, but the resulting grant amounts do not seem to have been the result of a purposeful, coordinated effort between OSHPD and UC to address regional workforce issues. Second, having two programs is resulting in higher administrative costs (around $2 million in each program). A portion of these administrative funds could instead be used to support more grants for residency programs.

Figure 5

State’s Grant Programs Share

Notable Similarities

|

Song‑Brown Program |

UC Proposition 56 Program |

|

|

Areas of Medicine |

||

|

Family Medicine |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Internal Medicine |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Pediatrics |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Obstetrics/Gynecology |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Emergency Medicine |

✓ |

|

|

Certain other areas |

✓ |

|

|

Geographic Areas |

||

|

Areas with shortages |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Institutions |

||

|

Public and private institutions in California |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Health Providers |

||

|

Physicians |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Physician assistants |

✓ |

|

|

Nurse practitioners |

✓ |

Recommendations

Focus on Limited‑Term Activities. We recommend the Legislature provide limited‑term funding (funding stretched over three to five years) rather than ongoing funding, as proposed by the Governor. State workforce issues tend to be dynamic, with the demand for physician services and the supply of physicians changing and adjusting over time. Providing funding on a limited‑term basis would allow the Legislature to periodically revisit evidence of shortages and adjust goals and funding accordingly. Providing limited‑term funding also would give the state more opportunity to study the comparative cost‑effectiveness of physician workforce policy strategies and adjust those strategies accordingly a few years from now.

Consider Consolidating Two Programs Into One. Given the drawbacks of supporting two programs with very similar goals, we recommend the Legislature consolidate the Song‑Brown and UC residency grant programs into one program. In consolidating the programs, the Legislature would have to decide (1) how the consolidated program should be administered, (2) what fund sources should support it, (3) which programs (including emergency care and nurse practitioners) should be eligible for funding, (4) how much total funding to provide annually, (5) what requirements should be linked to the grant funding, and (6) how to monitor outcomes of grant recipients. The Legislature could build the consolidated program by taking the most promising components of the two existing programs. Were the Legislature to desire supporting residency programs at current levels, it could allocate $73 million one time in 2019‑20 for the consolidated program, allowing funds to be spent over several years.

Give Highest Priority for Limited‑Term Funding to New Residency Programs for Start‑Up Costs. Regardless of whether the Legislature chooses to fund one new consolidated program or the two existing residency grant programs, it would have to decide how to allocate any new funds. We believe funding the development of new programs would be a more effective use of limited‑term funding than supporting existing programs, since Medicare could fund the ongoing operations of the new programs. To this end, we recommend the Legislature direct OSHPD to work with federal and local stakeholders to identify hospitals interested and eligible to develop Medicare‑funded residency programs. We recommend the Legislature require OSHPD to report on its findings by January 1, 2020—in time to inform next‑year’s budget decisions. In 2019‑20, the Legislature could set aside funds for this future purpose. (To the extent OHSPD believes more time is needed to complete this analysis, the Legislature could work with the agency to develop a feasible time line.)

Were Legislature to Fund Grants for Existing Programs, Establish Two Additional Parameters. As OSHPD studies potential new programs, the Legislature may be interested in providing funding for existing residency programs. In this case, we recommend the Legislature establish two parameters for the funding. First, we recommend the Legislature prioritize funding for added slots (rather than existing slots) at existing programs. This prioritization would help ensure the funds increase the number of residents across the state. Second, we recommend any funding for existing programs be allocated based on their financial need. In its grant application, a program could submit its (1) revenues by source (including the clinical revenues generated by residents), (2) specific revenue sources that are set to expire, and (3) spending. Prioritizing based on financial need would help ensure additional state grant funds are not supplanting a program’s existing resources.