May 29, 2019

The 2019-20 May Revision

Update to Governor’s 1991 Realignment Proposals

Introduction

The Governor’s January budget proposed a number of changes to 1991 realignment summarized in Figure 1. In May, the Governor revised his realignment proposals. In some areas, the changes proposed in the Governor’s May Revision reflect technical adjustments needed to implement what was originally proposed in January. In other areas, however, these changes reflect a change in policy relative to the Governor’s January proposals. (More information on the current structural imbalance within 1991 realignment can be found in our October 2018 report, Rethinking the 1991 Realignment, and the January 2019 Department of Finance (DOF) report, Senate Bill 90: 1991 Realignment Report.)

Figure 1

Comparison of the Governor’s January and May Revision Realignment Proposals

|

Governor’s Budget Proposals |

May Revision Proposals |

|

IHSS‑Related Changes |

|

|

Rebase IHSS county MOE to lower amount in 2019‑20. |

Remains the same, but associated General Fund costs estimated to be higher. |

|

Lower the annual adjustment factor for IHSS county MOE beginning in 2020‑21. |

Remains the same. |

|

Continue to increase IHSS county MOE by locally established IHSS wage and health benefit increases (in addition to annual adjustment factor). |

Proposes to give counties a share of cost for increases in health benefit premiums and other locally established non‑health benefit. The IHSS county MOE will be adjusted to reflect these costs in addition to locally established wage and health benefit costs and the annual adjustment factor. |

|

Eliminate General Fund assistance for IHSS county MOE and redirected VLF growth funds. |

Remains the same. |

|

Increase county share of cost for locally established IHSS wage and benefit increases once state minimum wage reaches $15.00 per hour. |

Remains the same. |

|

Health and Mental Health‑Related Changes |

|

|

Increase redirection of health realignment funding from four non‑CMSP counties (Placer, Santa Barbara, Sacramento, and Stanislaus) to 75 percent. |

Increased redirection for these counties no longer proposed. (Keep redirection percent at current level of 60 percent.) |

|

Increase redirection of realignment funding from CMSP counties to 75 percent, effectively redirecting all CMSP board revenues, until reserves are reduced below a three‑month target level. |

Directly shut off flow of base health realignment funding to CMSP until reserves are reduced below a two‑year target level, increasing redirection of realignment funding from CMSP counties to 75 percent thereafter. |

|

Eliminate growth to CMSP board until board reserves are reduced below a three‑month target level. |

Eliminate growth to CMSP board indefinitely. |

|

Continue practice of treating Yolo County as non‑CMSP county for purposes of the redirection and increase redirection to 75 percent. |

Yolo County proposed to be treated as CMSP county for purposes of the redirection. |

|

Establish fixed general growth allocation among mental health and CalWORKs. |

Remains the same. |

|

IHSS = In‑Home Supportive Services; MOE = maintenance‑of‑effort; VLF = vehicle license fee; and CMSP = County Medical Services Program. |

|

Below, we describe the update to the Governor’s 1991 realignment proposal introduced in January. Additionally, we assess whether the changes included in the Governor’s May Revision align with our realignment principles and address the issues we raised for Legislative consideration in January. This analysis reflects our current understanding of the Governor’s revised proposal. We will continue to review proposed statutory changes and other details as they are made available and will update this analysis as needed.

LAO Bottom Line. On balance, we find that the Governor’s proposed changes included in the May Revision address some concerns we raised in our assessment of the Governor’s January budget proposal and continue to move in the right direction relative to our core principles of a successful state-county fiscal partnership. For some components of the Governor’s May Revision, we raise concerns that are similar to those we had with the January proposal and suggest an alternative path forward. (Our analysis of the Governor’s January 1991 realignment proposals can be found in our report, The 2019‑20 Budget: Assessing the Governor’s 1991 Realignment Proposals.)

Changes to IHSS Realignment Proposal

In January, the Governor proposed (1) rebasing county In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS) costs—known as the IHSS county maintenance-of-effort (MOE)—to a lower amount in 2019‑20, (2) lowering the annual adjustment factor to the IHSS MOE from 7 percent to 4 percent, (3) eliminating the General Fund assistance and ending the redirection of certain health and mental health realignment revenues that counties were receiving to assist in covering IHSS county costs, and (4) changing the state-county cost sharing ratios for once IHSS provider wages the state minimum wage reaches $15 per hour.

Key Updates to January Proposal

Requests Additional $55 Million General Fund to Rebase County IHSS MOE. In January, absent his proposal, the Governor estimated that the base County IHSS MOE would have increased to $2 billion in 2019‑20. Absent any changes, DOF found that 1991 realignment revenues provided to counties were not enough to cover their increasing MOE costs. In January, the Governor proposed to reduce the base County IHSS MOE itself to an amount that could be covered by 1991 realignment revenues. Specifically, the Governor proposed to reduce the base County IHSS MOE from $2 billion to $1.56 billion in 2019‑20. As a result of these changes, it was estimated that, on net, about $240 million of county costs would be shifted to the state General Fund in 2019‑20.

In May, the Governor updated IHSS cost projections and 1991 realignment revenue estimates. Based on these revisions, the Governor estimates that, on net, an additional $55 million in General Fund is required to lower the base County IHSS MOE to an amount that can be covered by 1991 realignment. Specifically, based on higher IHSS cost projections, the Governor’s May Revision estimates that base County IHSS MOE costs would have been $2.06 billion in 2019‑20 under current law—about $60 million higher than January estimates. Additionally, the Governor’s May Revision estimates that 1991 realignment revenues can cover about $4 million in additional base county IHSS costs relative to January estimates (still about $1.56 billion in total). Based on these updated estimates, reducing the County IHSS MOE to $1.56 billion would, on net, shift about $295 million of county costs to the state General Fund in 2019‑20.

Sets Final 2019‑20 IHSS MOE Costs Based on May Revision Realignment Revenue Estimates. The Governor is proposing to treat the May Revision estimates of realignment revenues as final for purposes of rebasing the IHSS MOE even though actual 2019‑20 realignment revenues won’t be known until the Fall of 2020. In the case that 2019‑20 realignment revenues actually come in higher than the May Revision estimates, counties will have more than enough realignment revenues to cover base IHSS MOE costs in 2019‑20. However, if 2019‑20 realignment revenues come in lower than May Revise estimates, then counties will not have enough revenues to cover base IHSS MOE costs in 2019‑20.

Expands Cost Sharing Between the State and Counties for Health Benefit Premiums and Other Non-Health Benefits. Under current law, counties are required to have a share of cost for locally established wage and health benefit increases. The Governor’s revised budget proposes to change current law to expand the items for which counties are explicitly required to have a share of cost. Specifically, the Governor’s revised budget proposes that counties also have a share of cost in increases in health benefit premiums (costs that are established by health plans to provide locally established health benefits) and locally established non-health benefits. (Currently, the proposed language does not provide the definition of a non-health benefit. It is our understanding that a non-health benefit would be determined on a case-by-case basis by the Department of Social Services, in consultation with the California State Association of Counties.) These costs would be added to the IHSS MOE similar to county costs from locally established wage and health benefit increases.

Maintains All Other IHSS-Related Realignment Changes Proposed in January. As previously mentioned, the Governor proposed other changes to the IHSS MOE structure in January, including lowering the IHSS MOE annual inflator from 7 percent to 4 percent and changing the future state-county cost-sharing ratios. The Governor’s May Revision maintains these changes and proposes no technical updates.

LAO Comments

Improvements to 1991 Realignment Structure Resulting From Proposed Changes to IHSS MOE and Cost Sharing Remain the Same. In January, we found that the Governor’s proposed changes to the IHSS MOE structure improved the chances of realignment revenues covering county costs over time and better aligned with our overall realignment principles. We view the revised General Fund cost estimates associated with reducing the IHSS MOE as a technical adjustment needed to achieve what was originally proposed in the Governor’s January budget. Additionally, the intent of the proposed state-county cost sharing for health benefit premiums and non-health benefits is to ensure that counties have a share in both direct and indirect costs that stem from county decisions. Thus, we find that the structural changes to 1991 realignment under the Governor’s proposal largely remain the same and positon 1991 realignment for an improved state-county fiscal partnership.

Continue to Recommend the Legislature Monitor Long-Term Financial Balance of 1991 Realignment. Similar to our January analysis, whether realignment revenues will be sufficient to cover counties’ IHSS MOE costs long term remains unclear. That is, if in future years average growth in realignment revenue is lower than the proposed IHSS MOE annual adjustment factor (4 percent), IHSS county costs would exceed revenues. As a result, counties would face increasing cost pressures from their 1991 realignment responsibilities. (Additionally, if this occurred in 2019‑20, the Governor’s intention to reduce the base county IHSS MOE costs to an amount that could be covered by 1991 realignment revenues in 2019‑20 would remain unmet.) We recommend the Legislature monitor—through the annual budget process—whether realignment revenues are sufficient to cover counties’ IHSS costs over time.

Changes to Health Realignment Proposals

Background

Under 1991 Realignment, Counties Receive Funding to Carry Out Certain Health-Related Activities. Counties receive an annual allocation of health realignment funding to carry out certain health-related activities. These health-related activities include: (1) providing health care services to low-income, uninsured individuals (sometimes referred to as “indigent health”) and (2) public health activities, such as communicable disease control. Each year, as long as revenues are sufficient, counties receive an allocation of health realignment revenues equal to the total amount of funding they received in the prior year, known as base funding. If additional revenues are available, some portion of these revenues are allocated to counties in the form of health realignment growth funding. The total of base and growth funding in one year becomes the base for the following year.

CMSP Board Administers Indigent Health Services on Behalf of Participating Counties. Some counties administer both indigent health and public health activities themselves. In 35 mostly rural counties, however, the County Medical Services Program (CMSP) board carries out indigent health responsibilities on behalf of these counties, while the individual member counties are responsible for the remaining public health activities. Currently, the CMSP board receives its own annual allocation of base and growth health realignment revenues for indigent health activities. Counties that participate in CMSP also receive an annual allocation of base and growth health realignment revenues. Of this latter annual allocation to CMSP member counties, each county contributes a fixed dollar amount (which varies by county) to supplement health realignment funding that the CMSP board receives directly for indigent health services. These fixed dollar amounts, referred to as “jurisdictional risk,” total about $90 million annually across the 35 counties. After accounting for jurisdictional risk, the remainder of health realignment dollars provided to CMSP member counties is available for public health activities.

Redirection of Health Realignment Revenues Currently Offsets General Fund Costs in CalWORKs. Following the implementation of the federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2014, the number of low-income Californians without health coverage decreased dramatically. This reduced counties’ costs for health care services for this population and increased state costs. In response, the state redirected health realignment funding to offset state costs in the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program. The state currently redirects 60 percent of health realignment revenues from CMSP counties as well as from four non-CMSP counties—Placer, Sacramento, Santa Barbara, and Stanislaus—to generate state savings in this way. (The state also redirects health realignment funding from the remaining counties in the state, but does so under a different methodology that we do not describe in this post.)

Summary of the Governor’s January Proposal

In January, the Governor proposed to increase the amount of health realignment funding redirected from certain counties to offset the state costs of a proposal to expand Medi-Cal coverage to all young adults aged 19 through 25 regardless of immigration status. Among other things, the January proposal would have increased from 60 percent to 75 percent the redirection percentage for CMSP member counties and the four non-CMSP counties. It would also have stopped the allocation of health realignment growth funding to the CMSP board until the board’s significant reserves fell below a level consistent with three months of operations. (The CMSP board has built up a reserve of over $360 million, more than ten times its annual operating budget.) As we describe later, in practice this proposal would have stopped the flow of all realignment revenues—both base and growth—to the CMSP board.

Key Updates to January Proposal

In the May Revision, the Governor makes several key changes to his January proposal, described below.

Maintains 60 Percent Redirection From Four Non-CMSP Counties. Following the Governor’s January proposal, our office and others raised concerns that the increased redirection proposed in January could have reduced funding available for other local health-related responsibilities—specifically, public health activities—in the four non-CMSP counties for a variety of reasons that we outlined in our March 2019 analysis. In response to these concerns, the Governor’s revised budget proposes to continue redirecting 60 percent, rather than the 75 percent proposed in January, of health realignment funding to the state from these four counties.

In the Near Term, Continues to Stop All Revenues Flowing to the CMSP Board. The Governor’s January proposal to increase the redirection percentage for CMSP counties in practice would have stopped all revenues that otherwise would have flowed to the CMSP board in 2019‑20. This is because the CMSP board’s growth funding would be suspended (until its reserves are reduced) and, as described in a nearby box, the increased 75-percent redirection effectively would have redirected to the state all of the CMSP board’s base funding, which represent all of the board’s remaining realignment revenues.

While the May proposal takes a different approach from a technical perspective, the outcome is the same—the flow of all of the CMSP board’s revenues would be stopped beginning in 2019‑20. The May proposal continues to suspend the allocation of growth funding to the CMSP board in 2019‑20. In contrast to the January proposal, the May proposal would not immediately increase the redirection percentage for CMSP counties from 60 percent to 75 percent, but still would require that the flow of all remaining revenues to the CMSP board be stopped.

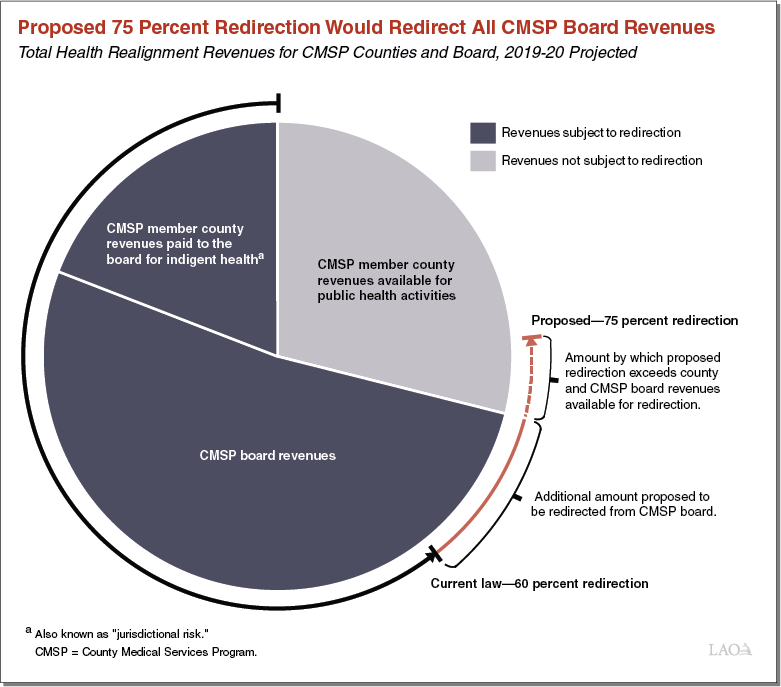

Projected Impact of 75 Percent Redirection on County Medical Services Program (CMSP) Board

Majority of Current Health Realignment Redirection Comes From CMSP Board Revenues, Rather Than From the CMSP Counties Directly. Under current law, the 60 percent redirection of health realignment revenues for CMSP counties applies to the total of health realignment revenues provided to CMSP counties and directly to the CMSP board. Specifically, the amount redirected includes (1) the amount that CMSP counties contribute from their own revenues for indigent health services (their jurisdictional risk amount) and (2) the balance required to reach the 60 percent aggregate redirection amount is contributed by the board. CMSP county revenues other than jurisdictional risk are not subject to redirection and are available for county public health activities.

Proposed 75 Percent Redirection Would Redirect All CMSP Board Revenues if Implemented in 2019‑20. In January, the Governor proposed increasing the redirection percentage for CMSP counties from 60 percent to 75 percent beginning in 2019‑20. As shown in the figure, this higher redirection amount would exceed the combination of CMSP member counties’ jurisdictional risk amount and all of the CMSP board’s projected health realignment revenues. In other words, under the Governor’s January proposal, the CMSP board would have received no revenues—base or growth—in 2019‑20. (The 75 percent redirection would exceed the combination of CMSP member counties’ jurisdictional risk and the CMSP board’s revenues, as indicated with the dotted line in the figure. However, remaining CMSP member county revenues would have been held harmless from the increased redirection and continued to be available for public health activities.)

Loosens, At Least in Concept, Some Restrictions on CMSP Board Revenues Once Reserves Are Reduced. The Governor’s January proposal would have allowed health realignment growth funding to again flow to the CMSP board once its reserves are reduced to less than three months of operating expenses, while leaving the redirection percentage for CMSP counties at the higher level of 75 percent. In concept, this represents a loosening of restrictions on the flow of funding to the CMSP board once reserves are reduced. The Governor’s May proposal similarly loosens restrictions on realignment funding to the CMSP board once its reserves are reduced, but takes a different approach from a technical perspective, as described below.

First, in contrast to the January proposal, the May proposal would not restore health realignment growth funding to the board once the board’s reserves have been reduced. Instead, health realignment growth funding would be suspended indefinitely, regardless of the CMSP board’s reserve levels.

Second, the May proposal delays putting in place the higher 75 percent redirection until the CMSP board’s reserves have been reduced—likely several years from now—rather than in 2019‑20. Unlike in the near term, during which all CMSP revenues would specifically be redirected until reserves are reduced, the 75 percent redirection would not specifically state that all of the CMSP board’s revenues would be redirected after reserves have been reduced. Theoretically, some revenues might be allowed to flow to the CMSP board. However, as we describe later, we think future revenues to the CMSP under a 75 percent redirection are unlikely in practice.

Finally, in response to concerns that three months of operating reserves was likely insufficient, the Governor’s revised proposal implements the 75 percent redirection, with the conceptual possibility of additional funding once the CMSP board reaches two years of operating reserves.

Treat Yolo County as Part of CMSP for Purposes of Health Redirection. For most CMSP counties, the current 60 percent redirection is limited to each county’s jurisdictional risk amount, with the remaining redirection for these counties coming from the CMSP board. However, for Yolo County, which joined CMSP in 2011 and is treated as a non-CMSP county for purposes of redirection of health realignment revenue, the state has redirected a larger amount of funding. The Governor’s revised proposal would now treat Yolo County in the same manner as the other counties that previously joined CMSP, such that Yolo County’s redirection would be limited to its jurisdictional risk amount.

LAO Comments

Governor’s Proposal Reflects Policy Decision to Increase County Funding for Public Health Responsibilities in Selected Counties. In our earlier analysis of the Governor’s January proposal, we noted that additional redirection from counties to reflect the expansion of Medi-Cal coverage was justified. However, we also noted that public health funding activities in some counties could be negatively affected by the proposed 75 percent redirection. By revising the proposal to (1) treat Yolo County as part of CMSP for purposes of the redirection and (2) no longer increase the redirection percentage for the four non-CMSP counties, the Governor’s proposal means that this potential source of public health funding would not be negatively affected in these counties. Since the four non-CMSP counties could still have reduced costs in light of the Medi-Cal expansion (depending on how much they spend on health care services for undocumented young adults that would now be covered by Medi-Cal), it is possible the Governor’s revised proposal to keep the redirection at 60 percent despite possible declines in indigent care caseloads effectively increases funding in those counties by a small amount relative to their health-related responsibilities. Ultimately, the fiscal relationship between health realignment revenues and county health-related responsibilities is difficult to determine with precision. In our view, allowing these counties to retain this funding in this way represents a reasonable fiscal priority, but one that the Legislature should weigh against other priorities for funding in the state budget.

Redirecting CMSP Board Revenues Until Reserves Decline Makes Sense . . . As we noted in our earlier analysis, we find the Governor’s proposal to stop the flow of CMSP board base and growth revenues until its reserves reach a lower level to be reasonable. We further find that two years is a reasonable target level for reserves before additional revenues would be made available to CMSP. Even with this higher targeted reserve level, it will likely take the CMSP board several years to spend down its reserve to this level.

. . . But Governor’s Proposal Makes it Unlikely CMSP Board Would Receive Future Revenues, Even After Reserves Are Reduced. In the Governor's May proposal, the CMSP board would not receive any base or growth revenues until its reserves are reduced, at which point the higher 75 percent redirection would then be put in place. However, if the CMSP board receives no revenues in the intervening years while its reserves are being spent down, it is very likely that the higher 75 percent reduction would continue to redirect all of the CMSP board’s revenues in the future after board reserves have been reduced, just as would be projected to occur in 2019‑20. In other words, even after the CMSP board’s reserves have been reduced, we believe the Governor’s proposal makes it unlikely the CMSP board would receive additional revenues.

No Need to Determine Ongoing Parameters of CMSP Funding Now. CMSP has experienced significant reductions in its caseloads—close to 99 percent—since health coverage for low-income individuals has expanded following implementation of the ACA. This in large part has led to CMSP’s large reserves and raises questions about the scope of CMSP’s ongoing role. A residual population of low-income uninsured individuals remains, but the appropriate ongoing funding amount for CMSP is unclear, particularly as the Legislature considers additional coverage expansions in the future. However, the Legislature need not set ongoing parameters for CMSP funding now. The Legislature could instead take the following two actions:

First, enact language that would specifically redirect all CMSP base and growth revenues to the state until reserves reach a specified lower level (such as two years of operating expenses), as proposed by the Governor.

Second, defer other changes to CMSP board funding (like the eventual redirection percentage applied to CMSP counties once the board’s reserves have been reduced) until after determining the amount of ongoing realignment revenues needed to provide coverage to the residual uninsured population at a level consistent with the Legislature’s priorities.