LAO Contact

Each year, our office publishes California Spending Plan, which summarizes the annual state budget. In July, we published a preliminary version of the report. This, the final version, provides an overview of the 2019‑20 Budget Act, then highlights major features of the budget approved by the Legislature and signed by the Governor. In addition to this publication, we have released a series of issue‑specific, online posts that give more detail on the major actions in the budget package.

Correction (10/29/19): Figure 4 total.

Update (12/9/19): AB 74 added to Figure 7.

October 17, 2019

The 2019‑20 Budget

California Spending Plan (Final Version)

Each year, our office publishes the California Spending Plan to summarize the annual state budget. This publication provides an overview of the 2019‑20 Budget Act, then highlights major features of the budget approved by the Legislature and signed by the Governor. All figures in this publication reflect actions taken through July 16, 2019, but we have updated the narrative to reflect actions taken later in the legislative session. In addition to this publication, we have released a series of issue‑specific, online posts (for example, a post on Health and Human Services issues) that give more detail on the major actions in the budget package.

Budget Overview

Spending

Figure 1 displays the administration’s July 2019 estimates of total state and federal spending in the 2019‑20 budget package. As the figure shows, the budget assumed total state spending of $208.9 billion (excluding federal and bond funds in 2019‑20), an increase of 2 percent over revised totals for 2018‑19. General Fund spending in 2019‑20 is $147.8 billion—an increase of $5.1 billion, or 4 percent, over the revised 2018‑19 level. This increase is lower than it would be otherwise because the budget attributes several billions of dollars in new expenditures to 2018‑19 rather than 2019‑20. Special fund spending is roughly flat from 2018‑19 to 2019‑20.

Figure 1

Total State and Federal Expenditures

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Revised |

Enacted |

Change From 2018‑19 |

|||

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

Amount |

Percent |

||

|

General Fund |

$124,756 |

$142,693 |

$147,781 |

$5,087 |

4% |

|

Special funds |

49,655 |

61,226 |

61,093 |

‑134 |

— |

|

Budget Totals |

$174,411 |

$203,920 |

$208,874 |

$4,954 |

2% |

|

Bond funds |

$2,905 |

$7,399 |

$5,904 |

‑$1,494 |

‑20% |

|

Federal funds |

92,352 |

100,007 |

106,303 |

6,296 |

6 |

|

Note: Reflects administration estimates of budgetary actions through July 16, 2019. |

|||||

Proposition 98 Funding Rises Steadily. Proposition 98 (1988) established a constitutional minimum annual funding requirement for K‑14 education. The minimum funding amount grows over time based upon various factors, including changes in General Fund revenue, per capita personal income, and student attendance. The state meets the funding requirement using a combination of state General Fund and local property tax revenue. Total Proposition 98 funding for 2019‑20 is $81.1 billion, an increase of $2.9 billion (3.7 percent) from the revised 2018‑19 level (Figure 2). For 2018‑19 and 2019‑20, the approved funding equals the minimum requirement. For 2017‑18, funding is $117 million above the minimum requirement.

Figure 2

Proposition 98 Funding by Segment and Source

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

Change From 2018‑19 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Funding by Segment |

|||||

|

K‑12 education |

$66,839 |

$68,973 |

$71,243 |

$2,270 |

3.3% |

|

Community colleges |

8,737 |

9,173 |

9,437 |

264 |

2.9 |

|

Proposition 98 reserve |

— |

— |

377 |

377 |

— |

|

Totals |

$75,576 |

$78,146 |

$81,056 |

$2,910 |

3.7% |

|

Fund Source |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$52,951 |

$54,445 |

$55,891 |

$1,446 |

2.7% |

|

Local property tax |

22,625 |

23,701 |

25,166 |

1,464 |

6.2 |

|

Note: Reflects estimates of budgetary actions through July 16, 2019. |

|||||

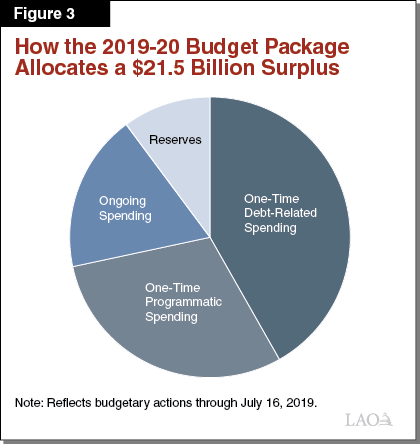

Budget Commits $21.5 Billion in Discretionary General Fund Spending. After accounting for constitutionally required spending (such as Proposition 98 funding for K‑14 education) and added costs to maintain existing policies and programs, we estimate the Legislature had $21.5 billion in discretionary General Fund resources to allocate in the 2019‑20 budget. The spending plan devotes this surplus to four major purposes (Figure 3). These are: (1) $9 billion to pay down some state debts and liabilities, (2) $4 billion in new ongoing programmatic spending, (3) $6.5 billion in one‑time programmatic spending, and (4) $2.1 billion in optional reserves. (Optional reserves include the $1.4 billion ending fund balance in the state’s discretionary reserve.)

Ongoing Spending Grows to $6 Billion at Full Implementation. The cost in 2019‑20 of new discretionary ongoing program spending is $4 billion. This is higher than the amount other recent budgets allocated to new ongoing spending from an available surplus. In particular, the 2016‑17 budget allocated $300 million to new ongoing spending and the 2018‑19 budget allocated $1.3 billion. Further, our estimates suggest the full implementation cost of the new 2019‑20 discretionary ongoing commitments is $5.9 billion. Some of this increase results from the budget instituting new ongoing spending increases midway through the fiscal year, such that the full‑year cost of the change occurs in 2020‑21. For example, the budget provides rate increases for most Department of Developmental Services (DDS) service providers beginning on January 1, 2020 and funds additional full‑day preschool slots beginning on April 1, 2020. In other cases, the cost of an ongoing policy changes over time. For example, the spending plan reduces counties’ share of costs for In‑Home Supportive Services (IHSS), resulting in escalating costs to the state’s General Fund, which increase by hundreds of millions of dollars over the period. That said, included in this estimate of ongoing spending are a number of program expansions that are subject to suspension, as described in the next paragraph. If the program suspensions occur, new ongoing spending in the budget package (in full implementation) is $4.2 billion.

Budget Makes Several Augmentations Subject to “Suspension.” The spending plan also makes a number of ongoing program augmentations subject to suspension on December 31, 2021. In these cases, statute directs the Department of Finance (DOF) to calculate whether General Fund revenues will exceed General Fund expenditures—without suspensions—in 2021‑22 and 2022‑23. If DOF determines revenues will exceed expenditures, then the programs’ ongoing expenses will continue. Otherwise, the expenditures are automatically suspended. Figure 4 summarizes the 20 ongoing expenditures in the 2019‑20 Budget Act that are subject to this suspension language. Altogether, the full‑year cost of these suspensions are $1.7 billion. These budget items also include language that indicate the Legislature intends to consider alternative solutions to restore the program expansions if the suspension takes effect.

Figure 4

Programs or Augmentations Subject to Suspension

(In Millions)

|

Program or Augmentation |

Full‑Year General Fund |

|

Proposition 56 Medi‑Cal provider payment increases |

$861 |

|

IHSS 7 percent service hour restoration |

358 |

|

DDS service provider rate increases (including DOR) |

250 |

|

Medi‑Cal optional benefits restoration |

41 |

|

DDS uniform holiday schedule |

30 |

|

Family Urgent Response Team |

30 |

|

Senior nutrition |

18 |

|

Funding for housing for foster youth |

13 |

|

Emergency Child Care Bridge program |

10 |

|

Extension of Medi‑Cal coverage for post‑partum mental health |

9 |

|

Child Welfare public health nursing early intervention |

8 |

|

Foster Family Agency rate increase |

7 |

|

Student financial aid during the summer (CSU) |

6 |

|

No Wrong Door Model |

5 |

|

STD prevention |

5 |

|

HIV prevention and control |

5 |

|

Hepatitis C virus prevention and control |

5 |

|

Student financial aid during the summer (UC) |

4 |

|

Expansion of screening and intervention to drugs other than alcohol |

3 |

|

Total |

$1,666 |

|

IHSS = In‑Home Supportive Services; DDS = Department of Developmental Services; and DOR = Department of Rehabilitation. |

|

Revenues

Figure 5 displays the administration’s revenue projections as incorporated into the June 2019 budget package. The budget package assumes $143.8 billion in General Fund revenues and transfers in 2019‑20, a 4 percent increase over revised 2018‑19 estimates. All together, the state’s three largest General Fund taxes—the personal income tax (PIT), sales and use tax, and corporation tax—are projected to increase 3 percent.

Figure 5

General Fund Revenue Estimates

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Revised |

Enacted |

Change From 2018‑19 |

|||

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

Amount |

Percent |

||

|

Personal income tax |

$93,776 |

$98,304 |

$102,413 |

$4,109 |

4% |

|

Sales and use tax |

24,974 |

26,100 |

27,241 |

1,141 |

4 |

|

Corporation tax |

12,313 |

13,774 |

13,133 |

‑641 |

‑5 |

|

Subtotals |

($131,063) |

($138,178) |

($142,787) |

($4,609) |

(3%) |

|

Insurance tax |

$2,569 |

$2,643 |

$2,868 |

$226 |

9% |

|

Other revenues |

1,862 |

2,092 |

2,159 |

67 |

3 |

|

Transfer to BSA |

‑4,094 |

‑3,551 |

‑2,158 |

1,393 |

‑39 |

|

Other transfers and loans |

‑284 |

‑1,315 |

‑1,851 |

‑537 |

41 |

|

Totals, Revenues and Transfers |

$131,116 |

$138,046 |

$143,804 |

$5,758 |

4% |

|

BSA = Budget Stabilization Account. Note: Reflects administration estimates of budgetary actions through July 16, 2019. |

|||||

The Condition of the General Fund

Figure 6 summarizes the condition of the General Fund under the revenue and spending assumptions in the June 2019 budget package, as estimated by DOF.

Figure 6

General Fund Condition Summary

(In Millions)

|

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

|

|

Prior‑year fund balance |

$11,419 |

$6,772 |

|

Revenues and transfers |

138,046 |

143,804 |

|

Expenditures |

142,693 |

147,781 |

|

Ending fund balance |

$6,772 |

$2,796 |

|

Encumbrances |

$1,385 |

$1,385 |

|

SFEU balance |

$5,387 |

$1,411 |

|

Reserves |

||

|

BSA balance |

$14,358 |

$16,516 |

|

SFEU balance |

5,387 |

1,411 |

|

Safety net reserve |

900 |

900 |

|

School reserve |

— |

377 |

|

Total |

$20,645 |

$19,204 |

|

SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties and BSA = Budget Stabilization Account. |

||

|

Note: Reflects administration estimates of budgetary actions through July 16, 2019. |

||

Total Reserves Are $19.2 Billion Under Spending Plan. As shown in Figure 6, the budget package assumed that 2019‑20 will end with $19.2 billion in total reserves. This consists of: (1) $16.5 billion in the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA), the state’s constitutional reserve; (2) $1.4 billion in the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU), which is available for any purpose including unexpected costs related to disasters; (3) $900 million in the safety net reserve, which is available for spending on the state’s safety net programs like California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs); and (4) $377 million in the state’s school reserve.

The 2018‑19 Budget Act enacted a reserve level of $15.9 billion. As such, the 2019‑20 reserve level of $19.2 billion represents an increase of about $3.3 billion. The increase results from the net effect of four factors: (1) required deposits of $2.7 billion into the BSA under the constitutional rules of Proposition 2 (2014); (2) an optional deposit of $700 million into the safety net reserve; (3) a first‑ever deposit into the school reserve, as described below; and (4) a reduction of $550 million, relative to the enacted 2018‑19 level, in the state’s SFEU.

State Makes First Ever Deposit Into School Reserve. In addition to changing the rules regarding deposits into the BSA, Proposition 2 also established a constitutional reserve account within Proposition 98. The purpose of this reserve is to set aside some Proposition 98 funding in relatively strong fiscal times to mitigate funding reductions during economic downturns. The 2019‑20 budget makes the first ever deposit into this account. The $377 million deposit is mainly the result of relatively strong capital gains revenue and certain other required conditions being met for the first time.

Evolution of the Budget

Governor’s January Budget Proposal

On January 10, 2019, Governor Newsom presented his first state budget proposal to the Legislature.

January Budget Proposal Reflected a Significant Surplus. We estimate that—at the time of the January budget—the Governor had $20.1 billion in discretionary resources available to allocate in the 2019‑20 budget process. (This surplus figure is lower than what we reflected in our report, The 2019‑20 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Budget, due in part to an accounting error in the Governor’s budget.) This remarkable surplus was the result of a number of factors: higher‑than‑expected revenue growth over multiple years and lower‑than‑anticipated spending on some programs, most notably Medi‑Cal. In January, the Governor proposed a total reserve level of $18.5 billion.

Governor Allocated Most of the Surplus Toward One‑Time Debt and Spending Purposes. The Governor proposed allocating half of that surplus toward repaying state debts—including pension liabilities and budgetary debts. The Governor also proposed spending an additional $5 billion on one‑time or temporary programmatic spending. These one‑time proposals focused on early education and child care, as well as housing and homelessness. The January budget proposed $2.7 billion in new ongoing programmatic spending. These increases focused on additional spending for the universities, various human services programs—including CalWORKs and IHSS—and health.

Governor Proposed Partial Tax Conformity Package, Expanded EITC, and Did Not Extend MCO Tax Package. The Governor’s January budget proposal included a plan to make changes to the state tax code that would conform to some provisions of the federal tax code. Taken altogether, these changes would raise revenue. The administration also proposed expanding the state’s Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which would reduce revenue. The administration coupled these proposals together—listing potential tax conformity actions for the Legislature to consider and expressing its intent that the state adopt enough of these provisions to cover the cost of the existing EITC program and the proposed expansion. Meanwhile, the Governor did not propose renewing the tax on managed care organizations (MCOs).

Governor’s May Revision

May Revision Reflected Slightly Better Budget Position. Despite the remarkable size of the estimated surplus available to allocate in January, the May Revision reflected a slightly better budget picture with a surplus that was larger by $800 million. This increase was the net result of a variety of factors, including somewhat higher revenues (offset by higher constitutional requirements) and slightly lower baseline spending.

Governor Allocated an Additional $1.3 Billion in New Programmatic Spending in May Revision. In the May Revision, the Governor proposed reducing discretionary reserves and using new required Proposition 2 debt payments for a portion of the Governor’s January discretionary debt proposal. This reduction and shift in spending enabled the Governor to allocate a total of $1.3 billion in new programmatic spending in May. The Governor generally used this additional funding to expand one‑time and ongoing programmatic commitments.

Governor Proposed New Sunsets for Existing Programs in 2021‑22. In putting together the May Revision proposals, the administration identified a multiyear budget deficit under its own budget estimates and proposals. Consequently, coupled with the program expansions, the Governor proposed to “sunset” three major categories of existing program expenditures. Expenditures made temporary included provider payment increases in Medi‑Cal, a restoration of previously reduced IHSS service hours, and new supplemental rate increases for developmental services providers. The Governor continued not to propose reauthorizing the MCO tax package in the May Revision.

June Budget Package

The Legislature passed the final budget package on June 13, 2019. The Governor signed the 2019‑20 Budget Act and 15 other budget‑related bills on June 27, 2019. These bills—as well as other budget‑related legislation passed later in the legislative session—are listed in Figure 7. The Governor vetoed $5.3 million in General Fund appropriations in the 2019‑20 Budget Act, including a $2.8 million appropriation for the El Dorado County Courthouse and a $2.5 million augmentation for the Public Employment Relations Board.

Figure 7

Budget‑Related Legislation

|

Bill Number |

Chapter |

Subject |

|

Legislation Passed Before July 16, 2019 |

||

|

AB 74 |

23 |

The 2019-20 Budget Act |

|

AB 101 |

159 |

Housing |

|

AB 110 |

80 |

Amendments to the 2019‑20 Budget Act |

|

AB 111 |

81 |

Wildfire safety and insurance |

|

SB 75 |

51 |

Early education and K‑12 education |

|

SB 76 |

52 |

Settle up and COLA (education finance) |

|

SB 77 |

53 |

Higher education |

|

SB 78 |

38 |

Health |

|

SB 79 |

26 |

Mental health |

|

SB 80 |

27 |

Human services |

|

SB 81 |

28 |

Developmental services |

|

SB 82 |

29 |

State government |

|

SB 83 |

24 |

Employment |

|

SB 84 |

30 |

Political Reform Act of 1974: Online filing system |

|

SB 85 |

31 |

Public resources |

|

SB 87 |

32 |

Transportation |

|

SB 90 |

33 |

Public Employees’ Retirement |

|

SB 92 |

34 |

Taxation |

|

SB 93 |

35 |

Amendments to the 2018‑19 Budget Act |

|

SB 94 |

25 |

Public safety |

|

SB 95 |

36 |

Courts |

|

SB 96 |

54 |

Emergency telephone users surcharge |

|

SB 103 |

118 |

Employment |

|

SB 104 |

67 |

Health |

|

SB 105 |

37 |

Corrections facilities |

|

SB 106 |

55 |

Amendments to the 2019‑20 Budget Act |

|

Legislation Passed After July 16, 2019 |

||

|

SB 109 |

363 |

Amendments to the 2019‑20 Budget Act |

|

SB 112 |

364 |

State government |

|

SB 113 |

668 |

Housing |

|

AB 114 |

413 |

Education finance |

|

AB 115 |

348 |

Managed care organizations |

|

AB 118 |

859 |

Employment |

|

AB 121 |

414 |

Human services |

|

COLA = cost of living adjustment. Note: This figure includes budget and trailer bills identified in Section 39.00 of the 2019‑20 Budget Act that were enacted into law. For this reason, it excludes AB 91 (Burke) which made changes to state income tax laws and SB 200 (Monning) that created the Safe and Affordable Drinking Water program. This list does include, however, SB 93, which amended the 2018‑19 Budget Act. |

||

Final Budget Reflected Partial Tax Conformity, EITC Expansion, and Intent for MCO Tax Package. In their respective packages, neither house adopted the Governor’s partial tax conformity plan but both houses planned a reauthorization of the MCO tax package. The final spending plan includes most of the Governor’s partial tax conformity proposals and an expansion of the state EITC, which is similar to the proposed version at the time of the May Revision. Finally, the spending plan (including actions taken later in the legislative session) reauthorizes the MCO tax in 2019‑20.

Final Budget Includes Suspension Language, Rather Than Sunset Provisions. Instead of the automatic sunset provisions proposed by the Governor in the May Revision, the 2019‑20 Budget Act reflects a number of automatic suspensions, which however would not occur if the General Fund condition is somewhat better than the administration currently projects. (These suspensions were described in the “Budget Overview” section of this report.) The dollar value of these contingent program suspensions is $1.7 billion.

Major Features of the 2019‑20 Spending Plan

This section describes the major features of the 2019‑20 spending plan. These are organized into three areas: (1) tax and other revenue policy changes, (2) debt and liability payments, and (3) programmatic spending changes.

Tax and Other Revenue Policy Changes

Expands the EITC. The EITC is a PIT provision that is intended to reduce poverty among California’s poorest working families by increasing their after‑tax income. The 2019‑20 budget plan expands the state’s EITC in three ways: (1) increases the income eligibility limit to $30,000 for all filers, (2) provides a new additional credit of $1,000 for eligible filers with at least one dependent under age six, and (3) increases the credit amount for filers with earnings toward the higher end of the 2018 eligibility range. These changes are estimated to reduce General Fund revenue by about $600 million per year. The budget also includes $10 million for grants to expand awareness of the EITC.

Makes Changes to Individual and Business Tax Provisions (Partial Tax Conformity). The budget package includes legislation that makes 11 changes to state income tax laws that, in general, adopt—or “conform” to—recent changes to similar federal tax laws. The most significant provisions affect businesses and certain kinds of business income. Some of the changes will reduce state taxes for the affected filers while other changes will increase them. Figure 8 lists the conformity provisions and their estimated revenue effects. In all, these provisions are expected to increase General Fund revenue by $1.6 billion in the budget year.

Figure 8

Individual and Business Tax Provision Changes (Partial Tax Conformity)

(In Millions)

|

Tax Provision |

Estimated Change in Revenue |

|

|

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

|

|

Limits noncorporate business losses |

$1,300 |

$850 |

|

Eliminates like‑kind exchanges of personal and intangible property for single filers earning more than $250,000 ($500,000 for joint filers) |

238 |

200 |

|

Eliminates net operating loss carrybacks |

200 |

190 |

|

Limits deductions of Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation premiums paid by banks |

65 |

55 |

|

Eliminates differences between state and federal law regarding the tax treatment of corporate mergers and acquisitions (Section 338 election) |

38 |

60 |

|

Eliminates the performance‑based compensation exception from existing limits on business deductions of executive pay |

32 |

29 |

|

Repeals “technical termination” of partnerships |

10 |

5 |

|

Modifies rules regarding contributions to Achieving Better Life Experiences (ABLE) accounts |

—a |

—a |

|

Allows individuals to convert an educational savings account (529 plan) to an ABLE account without incurring a penalty |

—a |

—a |

|

Excludes the discharge of student loan debt in case of death or disability from taxable income |

—a |

—a |

|

Increases to $25 million the annual revenue threshold for certain simplified tax accounting rules for small businesses |

‑280 |

‑110 |

|

Net Change in Revenue |

$1,602 |

$1,278 |

|

aEstimated revenue reduction of less than $1 million. |

||

Creates Sales Tax Exemptions for Menstrual Products and Children’s Diapers. The budget package creates two new sales tax exemptions: one for menstrual products and another for children’s diapers. These exemptions apply to the full amount of the state and local sales tax. The administration estimates that these exemptions will reduce state and local sales tax revenue by $76 million per year ($35 million General Fund). The budget package includes annual transfers from the General Fund to the Local Revenue Fund 2011 to offset estimated revenue losses to counties/cities resulting from the new exemptions. These exemptions go into effect on January 1, 2020 and expire on January 1, 2022. The budget package requires our office to submit reports reviewing the effectiveness of these exemptions—based on criteria included in the statute—by January 1, 2021.

Provides for Additional Future Affordable Housing Tax Credits. The budget increases by $500 million the state’s low‑income housing tax credit program which provides tax credits to builders of rental housing affordable to low‑income households. Of this total, $200 million is set aside for developments that include affordable units for both low‑ and lower‑middle‑income households. (Because these credits would not be claimed until well after 2019‑20, the General Fund condition figures displayed in this report do not reflect the costs of these expanded credits.)

Creates a State Individual Health Insurance Coverage Mandate. Beginning in 2020, budget‑related legislation creates an ongoing state requirement—known as the “individual mandate”—that most individuals maintain health insurance coverage or pay a penalty. The individual mandate is expected to result in additional individuals taking up health coverage. The mandate also generates revenue, estimated at $317 million beginning in 2020‑21 and growing over time.

Debt and Liability Payments

A major feature of the spending plan is a package of payments aimed at addressing the state’s outstanding debts and liabilities. Figure 9 summarizes this package.

Figure 9

Debt and Liability Repayment Proposals in 2019‑20 Budget Package

(In Millions)

|

Liability Type . . . |

Liability Owed by . . . |

Discretionary Payments |

Proposition 2 Debt Payments |

|

Retirement Liabilites |

|||

|

CalPERS |

State |

$2,500 |

— |

|

CalSTRS |

State |

— |

$1,117 |

|

CalSTRS |

School districts |

1,640 |

— |

|

CalPERS |

School districts |

660 |

— |

|

OPEB |

State |

— |

260 |

|

UCRP |

Universities |

25 |

— |

|

Subtotals |

($4,825) |

($1,377) |

|

|

Budgetary Debts |

|||

|

Pension deferral |

State |

$707 |

— |

|

Payroll deferral |

State |

973 |

— |

|

Special fund loans |

State |

1,283 |

— |

|

Weight fee loans |

State |

886 |

— |

|

Settle up |

State |

296 |

$391 |

|

CalPERS borrowing plan |

State |

— |

390 |

|

Subtotals |

($4,145) |

($781) |

|

|

Totals |

$8,970 |

$2,158 |

|

|

Note: This table excludes $850 million in pension‑related budget relief for school districts, which we describe in the section on programmatic spending. OPEB = other post‑employment benefits and UCRP = University of California Retirement Plan. |

|||

Allocates $2.2 Billion in Constitutionally Required Debt Payments. In addition to rules on deposits into reserves, Proposition 2 requires the state to make minimum annual payments to pay down certain eligible debts and liabilities. These minimum requirements are based on a set of formulas. In general, requirements are higher when estimates of the upcoming year’s revenues—particularly those from capital gains—are higher. The total Proposition 2 debt payment requirement was $2.2 billion in the 2019‑20 budget package. In addition, the spending plan dedicates an additional $9.1 billion to repay state debts on a discretionary basis (Figure 9).

Makes $5.9 Billion in Additional Unfunded Liability Payments. State employee pension benefits are administered by the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS). Teachers, administrators, and other certified employees of school districts earn pension benefits from the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS). Other school district employees, such as clerical staff, also earn pension benefits administered by CalPERS. The state and school districts each have full responsibility for their respective CalPERS’ unfunded liabilities associated with their own employees. In the case of CalSTRS, the state and school districts share responsibility for the system’s total unfunded liability (about one‑third is the responsibility of the state and two‑thirds of the districts).

The spending plan allocates $5.9 billion General Fund to pay down unfunded pension liabilities on behalf of both the state and school districts (some of which is counted toward the state’s Proposition 2 debt payment requirements). In particular, the spending plan dedicates:

- $3.6 Billion to Address State’s Unfunded Liabilities. The spending plan uses $2.5 billion in General Fund monies to pay down the state’s CalPERS unfunded liability. The spending plan also devotes $1.1 billion General Fund to reduce the state’s share of the CalSTRS unfunded liability, as part of the state’s Proposition 2 debt payment requirements.

- $2.3 Billion to Address School Districts’ Unfunded Liabilities. The spending plan also devotes $1.6 billion General Fund to reduce the school districts’ share of the CalSTRS unfunded liability and $660 million General Fund to address the school districts’ CalPERS unfunded liability.

Repays $4.9 Billion in Outstanding Budgetary Borrowing. Budgetary borrowing consists of debts the state has incurred in the past to address its budget shortfalls. The spending plan uses $4.9 billion ($781 million is counted toward Proposition 2) to fully repay most remaining budgetary borrowing, most of which falls into three categories: (1) deferrals, (2) loans, and (3) settle up. In particular, the spending plan uses $1.7 billion to undo two budgetary deferrals: one related to state employee payroll and one related to state pension payments. The spending plan also uses $2.2 billion to repay all remaining outstanding special fund loans, including $886 million to fully repay the state’s outstanding “weight fee loans,” which are loans to the General Fund from a fund receiving transportation weight fee revenues. Finally, the spending plan makes a $687 million “settle up” payment related to meeting Proposition 98 requirements in certain years prior to 2017‑18. (Upon making this payment, the state will have paid all outstanding settle‑up.) With these actions, the state has addressed nearly all of its remaining “Wall of Debt”—a term used by the prior administration to refer to the state’s outstanding budgetary liabilities. The remaining items on the Wall of Debt (as it was defined in the 2013‑14 Governor’s Budget) include nearly $3 billion to undo all of the deferrals related to the Medi‑Cal program and $1.5 billion in outstanding mandate costs to local governments and school districts.

Programmatic Spending

The major General Fund and special fund programmatic spending actions in the 2019‑20 budget package are shown in Figure 10 and briefly described below. We plan to discuss these and other actions in more detail in a series of forthcoming publications this fall.

Figure 10

Major Programmatic Spending Actions in the 2019‑20 Budget Package

|

Education |

|

Provides $2 billion (Proposition 98 General Fund) for LCFF. |

|

Provides $646 million (Proposition 98 General Fund) for various special education augmentations. |

|

Uses $850 million (General Fund) to cover a portion of districts’ CalPERS and CalSTRS pension payments in 2019‑20 and 2020‑21. |

|

Provides $1.3 billion (all funds) for early education programs ($469 million ongoing). |

|

Increases funding for CSU by $713 million General Fund ($392 million ongoing). |

|

Increases funding for UC by $416 million General Fund ($246 million ongoing). |

|

Health and Human Services |

|

Increases monthly CalWORKs grants ($332 million General Fund in 2019‑20, $442 million General Fund ongoing). |

|

Increases most DDS service provider rates ($126 million General Fund in 2019‑20, $253 million General Fund ongoing).a |

|

Expands health care coverage and increases affordability ($550 million General Fund in 2019‑20). |

|

Housing and Homelessness |

|

Provides $1 billion to fund programs that facilitate the construction of affordable housing. |

|

Includes $650 million in one‑time grants for a variety of programs that address homelessness. |

|

Provides $250 million in planning grants to local governments and other entities. |

|

Other |

|

Allocates $2.9 billion from the GGRF for various programs. |

|

Provides roughly $700 million for various disaster‑related purposes. |

|

Establishes the Safe and Affordable Drinking Water Program ($100 million GGRF and $30 million General Fund). |

|

aSubject to suspension language. |

|

LCFF = Local Control Funding Formula; DDS = Department of Developmenal Services; and GGRF = Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund. |

K‑14 Education

Provides a Few Notable Ongoing Proposition 98 Augmentations. As described earlier, under the spending plan, Proposition 98 funding for 2019‑20 increases $2.9 billion (3.7 percent) from the revised 2018‑19 level. The spending plan devotes the largest share of this increase—$2 billion—to school districts to cover changes in student attendance and provide a 3.26 percent cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA) for the Local Control Funding Formula (general purpose per‑student funding). The budget also provides two augmentations related to special education: (1) $493 million for school districts based on the number of three‑ and four‑year old children identified with disabilities affecting their education and (2) $153 million for special education agencies with average or below average per‑pupil funding rates. For community colleges, the budget provides $255 million to cover enrollment growth and provide a 3.26 percent COLA for apportionments (general purpose per‑student funding).

Pays a Portion of Districts’ Pension Costs for the Next Two Years. The spending plan also provides additional monies to school districts outside of the Proposition 98 funding requirement by paying a portion of districts’ pension costs for the next two years. School districts’ pension contribution rates for both CalPERS and CalSTRS have been rising and are set to continue increasing for at least the next few years. For CalSTRS, the budget provides $606 million for the state to pay a portion of districts’ costs (reducing district contribution rates by about 1 percent of payroll in 2019‑20 and 2020‑21). Similarly, the budget provides $244 million for the state to cover a portion of districts’ CalPERS costs (reducing district rates by about 1 percent of payroll in 2019‑20 and 2020‑21). Although district pension rates will continue to rise, the increases will be slower than previously projected. (As described earlier, the state also provides school districts with long‑term relief by paying down unfunded CalSTRS and CalPERS pension liabilities.)

Early Education

Makes Significant Augmentation for Early Education Programs, With Notable Increase in Non‑CalWORKs Slots. The budget package provides an additional $963 million in state and federal funds for early education programs, increasing spending 21 percent over the revised 2018‑19 level. About half of this additional spending is for ongoing purposes. Of the ongoing spending increases, $301 million is for more non‑CalWORKs slots. (All major child care and preschool programs received an increase in slots, including the State Preschool program, which received an expansion similar to the Governor’s proposal.) Within the $301 million is $50 million in one‑time funding for additional General Child Care slots, with the intent to replace this funding in the future with growth from cannabis tax revenue (Proposition 64 [2016]).

Increases CalWORKs Child Care Caseload and Cost. The budget package provides $112 million ongoing for expected cost increases in CalWORKs child care. The most notable of these cost increases are due to certain changes in the rules applying to CalWORKs Stage 1 families. Specifically, the budget package grants all Stage 1 families full‑time child care and verifies their eligibility for care only once each year (rather than continually throughout the year). The rest of the CalWORKs child care cost increase is due primarily to the ramping up effect of changes the state made to Stages 2 and 3 eligibility rules a few years ago.

Funds Various One‑Time Early Education Initiatives. The budget provides $493 million for one‑time child care and preschool initiatives. The budget package also provides $263 million to help child care providers construct or renovate facilities and $195 million to improve and expand child care and preschool workforce training. Both the facility and workforce initiatives spread available funds over the next four years. The remaining one‑time spending is for various initiatives, including $20 million for data improvement efforts. (The budget also provides $300 million for additional facility grants to help convert part‑day kindergarten to full‑day programs.)

Higher Education

Increases California State University (CSU) Funding Substantially. The budget increases ongoing General Fund support for CSU by $392 million (9.9 percent) and provides $321 million for one‑time initiatives. The budget plan assumes no increase in student tuition charges, with core ongoing funding for CSU (General Fund and tuition revenue combined) increasing 6.2 percent. The largest ongoing augmentation is for faculty and staff compensation. The budget also funds a 2.6 percent enrollment growth (10,000 additional full‑time equivalent resident undergraduates over estimated 2018‑19 enrollment). The largest one‑time augmentation is for addressing deferred maintenance at CSU campuses. The remaining one‑time spending involves a dozen other initiatives, including additional student food and housing assistance as well as funding to study the need for and feasibility of building new CSU campuses in certain regions of the state (specifically Chula Vista, Concord, Palm Desert, San Joaquin County, and San Mateo County).

Also Increases University of California (UC) Funding Substantially. The budget package increases ongoing General Fund support for UC by $245 million (7 percent) and provides $218 million for one‑time initiatives. As with CSU, the budget plan assumes no increase in student tuition charges, with core ongoing funding for UC increasing 4 percent. Nearly half of UC’s ongoing General Fund augmentation is for covering operational cost increases, including negotiated salary increases for represented employees and health care cost increases for active employees and retirees. The remainder of the ongoing augmentation is for 2.6 percent undergraduate enrollment growth (4,860 additional full‑time equivalent students in 2020‑21 over the 2018‑19 level), grants to physician residency programs, and expansion of various student services (including student food and housing assistance). About two‑thirds of the one‑time augmentation is for addressing deferred maintenance at UC campuses. The remaining one‑time funds are for numerous other initiatives, including start‑up funding for new extended education programs and a pilot program to test new K‑12 special education diagnostic services.

Health and Human Services

Reauthorizes the MCO Tax. From 2016‑17 to 2018‑19, the state imposed a tax on MCOs that generated a net General Fund benefit (excluding the effects of constitutional spending requirements) of over $1 billion annually. The spending plan reauthorizes the MCO tax—for three and one‑half years—under a broadly similar structure as the previous tax. As with the previous MCO tax, the reauthorized tax is a tiered, per‑member, per month tax on the Medi‑Cal and commercial enrollment of MCOs. Unlike the previous MCO tax package, the reauthorized MCO tax is not accompanied by reductions to other taxes paid by the health industry. Because the MCO tax is imposed on Medicaid services, it must be approved by the federal government. Since federal approval is not certain, revenues from the reauthorized MCO tax remain unallocated in the spending plan.

Increases Monthly CalWORKs Grants. The spending plan includes $332 million General Fund in 2019‑20 to increase the CalWORKs maximum grant levels, beginning October 1, 2019. (This amount corresponds to three‑quarters of the full‑year cost of the increase.) This will increase grants to between 47 percent and 50 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) for all CalWORKs families. In addition to the grant increase, the spending plan includes $6.8 million in 2019‑20 to raise the CalWORKs earned income disregard—the amount a family may earn before their CalWORKs grant is reduced by 50 cents for each additional $1 of income—from $225 to $500. (Costs associated with this change are expected to increase to nearly $100 million General Fund annually in future years.) This change effectively increases grants for families who earn more than $225 per month.

Increases DDS Service Provider Rates. The spending plan provides $126 million from the General Fund ($208 million total funds) in 2019‑20 for rate increases for most DDS service providers. Specifically, these increases are provided to those identified as needing a rate increase in a recently completed study of the rate‑setting system, conducted per Chapter 3 of 2016 (AB 2X 1, Thurmond). Rate increases are effective January 1, 2020 (and contingent on federal approval), thus, 2019‑20 costs represent half‑year costs. The annualized cost is $253 million General Fund ($416 million total funds). Most rates will increase by 8.2 percent, while some rates will increase by a lower percentage. The rate increases are subject to the suspension language discussed earlier.

Expands Health Care Coverage and Increases Affordability. The 2019‑20 spending plan includes several actions related to expanding health care coverage and making it more affordable. First, the spending plan provides new state subsidies to reduce the cost of coverage purchased through Covered California for households with incomes up to 600 percent of the FPL, at a cost of $429 million (General Fund) in 2019‑20. These subsidies will be available beginning in January 2020 and continue for three years—through the end of calendar year 2022—after which time they will sunset. (The spending plan offsets the costs of these new state subsidies using increased revenues from the new state individual mandate, as described in the section on tax and other revenue policy changes.) In addition, the spending plan includes several actions to expand enrollment in comprehensive, no‑cost health coverage through Medi‑Cal, the state’s largest health coverage program for low‑income residents. Most significantly, the spending plan includes $74 million from the General Fund ($98 million total funds) in 2019‑20 to expand comprehensive Medi‑Cal coverage to all income‑eligible adults ages 19 through 25 regardless of immigration status.

Housing and Homelessness

Provides Funding for Affordable Housing. In addition to expanding the affordable housing tax credit described earlier, the budget funds two major programs that facilitate the construction of affordable housing:

- Mixed‑Income Housing Loans. The spending plan allocates $500 million to the California Housing Finance Agency’s Mixed‑Income Loan Program, which provides loans to builders of housing targeted at low‑ and middle‑income households.

- Infrastructure Funding. The plan also allocates $500 million to the Infill Infrastructure Grant program administered by the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD). This program helps to fund infrastructure needed to support higher‑density housing built on infill sites—that is, sites within already developed communities.

Provides Funding to Address Homelessness. The budget includes $650 million for one‑time grants to local governments to fund a variety of programs and services that address homelessness. This funding is divided among the state’s 13 most populous cities, counties, and Continuums of Care—local entities that administer housing assistance programs within a particular area, often covering a county or group of counties.

Provides Funding to Support Local Planning for Housing. The budget provides $250 million for planning grants to local governments and regional planning entities. These grants are to be used for planning for the sixth cycle regional housing need assessment process and other planning activities that facilitate the development of housing. Funding is made available through HCD by application.

Creates a New Process for Housing Element Compliance. The budget package creates a new judicial process by which cities and counties can be fined for failing to comply with housing element law. Moreover, the courts could appoint an agent of the court to bring the jurisdiction’s housing element into compliance. (As of this writing, this bill was still awaiting signature from the Governor.)

Creates New Incentives for Adopting “Pro‑Housing” Policies. The budget package creates new incentives for cities and counties to adopt pro‑housing policies. Cities and counties that adopt these policies would receive additional points in the scoring of their applications for certain state grant programs. The budget package tasks HCD with creating criteria to identify pro‑housing policies that reflect differences between rural, urban, and suburban jurisdictions.

Criminal Justice

Implements an Integrated Substance Use Disorder Treatment Program. The budget provides $71 million General Fund for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) to implement an integrated substance use disorder treatment program within state prisons. Funding will be used to support various activities, including (1) expanding the provision of medication‑assisted treatment for opioid and alcohol use disorder statewide, (2) additional resources for reentry planning, and (3) an overhaul of existing rehabilitation programs (such as requiring contractors to use evidence‑based curricula).

Provides the “Prison to Community Pipeline” Package. The budget provides $50 million in ongoing General Fund resources to support various rehabilitation and reentry programs. This includes $37 million to the Board of State and Community Corrections for grants to community‑based organizations to provide rental assistance and other support services for individuals who were previously incarcerated in state prison. (In 2019‑20, $4.1 million is set aside on a one‑time basis for grants to prepare inmates for parole hearings using therapeutic counseling and to provide reentry services for individuals exonerated in California.) The remaining $13 million is for CDCR to create therapeutic support groups within state juvenile facilities ($8 million) and to provide grants to nonprofit organizations to deliver in‑prison rehabilitation programs ($5 million).

Natural Resources and Climate Change

Establishes the Safe and Affordable Drinking Water (SADW) Program. The budget provides $130 million—$100 million from the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) and $30 million from the General Fund—to establish a new SADW program, which will provide local assistance to communities and low‑income households that are served by water systems that do not provide safe and affordable drinking water. The program will be administered by the State Water Resources Control Board and provide water systems—particularly those in disadvantaged communities—with grants, loans, contracts, or services to help them provide safe and affordable drinking water. Allowable uses of the funds include providing replacement water on a short‑term basis, as well as the development, implementation, maintenance, and operation of permanent solutions such as water treatment systems and water system consolidations. Beginning in 2020‑21, this program will be supported by 5 percent of the annual revenue into the GGRF up to $130 million. Starting in 2023‑24, if GGRF revenues are not sufficient to generate $130 million for the program, the General Fund will be used to make up the difference.

Allocates Funding for Cap‑and‑Trade Expenditure Plan. The spending plan allocates a total of $2.9 billion from the GGRF for various programs. This plan includes (1) $1.3 billion in continuous appropriations, (2) about $221 million in other existing spending commitments, and (3) $1.4 billion in discretionary spending. The major categories of discretionary spending include promoting low‑carbon transportation ($485 million), reducing air toxic and criteria pollutants ($275 million), and forestry‑related activities ($221 million). Most of the discretionary funding is allocated to programs that received GGRF in prior years. However, some programs would receive GGRF for the first time, including $100 million for safe and affordable drinking water (discussed above), $35 million for workforce development activities intended to transition the state’s workforce to a low‑carbon economy, and $10 million to promote local fire prevention and response activities in the wildland‑urban interface.

Other

Provides Funding for Disaster Preparedness, Response, and Recovery. The budget package provides roughly $700 million in state funding—mostly from the General Fund and GGRF—for various disaster‑related purposes. Most of this funding supports (1) fire and other emergency response improvements, including communications systems ($265 million); (2) implementation of a recent package of legislation related to wildfires ($226 million); (3) assistance to local communities recovering from recent disasters ($80 million); and (4) efforts to mitigate the effects of power shutdowns conducted by investor‑owned utilities ($75 million).

Extends Paid Family Leave Program From Six to Eight Weeks. The spending plan lengthens the duration of the state’s Paid Family Leave program from six weeks to eight weeks. (Leave benefits are funded by a 1 percent payroll tax, paid by employees, and can be used to bond with a new child or care for a seriously ill family member.) In addition to lengthening the duration of leave, the spending plan reduces the required reserve level in the Disability Insurance Fund—which disburses paid family leave benefits—from 45 percent to 30 percent of annual disbursements. Lowering the reserve requirement will have the effect of temporarily reducing the contributions needed to fund the state’s paid family leave program. On net, relative to making no changes, the administration estimates that lengthening the duration of leave by two weeks will result in a 0.1 percent increase in the payroll tax rate beginning in 2022.

Implements Improvements to Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) REAL ID Workload and Operations. The budget includes $260 million from the Motor Vehicle Account for DMV to process driver licenses and ID cards that comply with federal standards—commonly referred to as “REAL IDs”—and to implement various operational improvements. (This amount includes $18 million in savings related to passing on credit card fees to customers.) Specifically, the budget includes: (1) $196 million for REAL ID workload, (2) $29.5 million for operational improvements (such as purchasing self‑service terminals), (3) $17.7 million for customer service improvements (such as implementing a live chat customer service system), and (4) $17 million for technology improvements. Additionally, the budget authorizes the Director of Finance to augment the level of funding provided to DMV—following a 30‑day notification to the Joint Legislative Budget Committee—in order to further reduce customer wait times at DMV field offices or to prevent these wait times from increasing.