LAO Contact

August 8, 2019

MOU Fiscal Analysis: Bargaining Unit 7 (Protective Services and Public Safety)

This analysis of the proposed labor agreement between the state and Bargaining Unit 7 (Protective Services and Public Safety) fulfills our statutory requirement under Section 19829.5 of the Government Code. State Bargaining Unit 7’s current members are represented by the California Statewide Law Enforcement Association (CSLEA). The administration has posted the agreement and a summary of the agreement on its website. The union also has posted a summary of the agreement on its website. The proposed agreement may go into effect only after it has been ratified by the Legislature and a majority of voting CSLEA members. (Our State Workforce webpages include background information on the collective bargaining process, a description of this and other bargaining units, and our analyses of agreements proposed in the past.)

Major Provisions of Proposed Agreement

Term. The agreement would expire July 1, 2023, meaning that it would be in effect for four years. The agreement includes provisions with effects on the state’s budget in five fiscal years (from the current year—2019‑20—through 2023‑2024). The long duration of the proposed agreement is not consistent with our 2007 recommendation that the Legislature only approve tentative agreements that have a term of fewer than two years.

Salary and Pay

Annual General Salary Increases (GSIs) to Entire Bargaining Unit for Three Years. The agreement would provide all Unit 7 members—regardless of classification—pay increases for three fiscal years. Specifically, the agreement would provide employees a 2.75 percent increase in 2019‑20, 2.5 percent increase in 2020‑21, and 2.5 percent increase in 2021‑22.

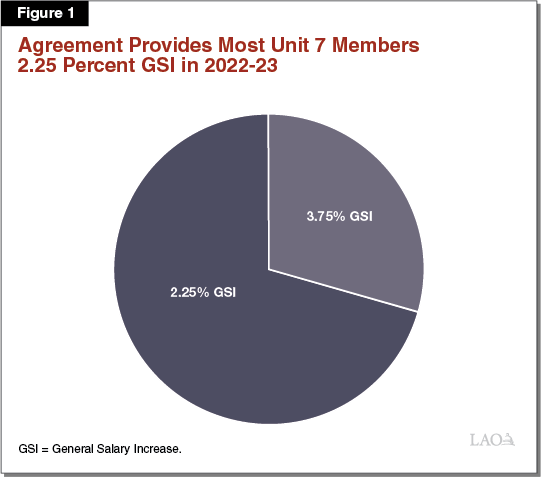

A Fourth GSI in 2022‑23—Amount Determined by Retirement Category. In addition to the three GSIs discussed above, the agreement would provide all employees a pay increase in 2022‑23. However, the amount that employees receive would depend on an employee’s retirement benefit. Specifically, employees in the Peace Officer/Firefighter (POFF) pension tier would receive a 3.75 percent GSI and other employees in the bargaining unit would receive a 2.25 percent GSI. As Figure 1 shows, about 30 percent of Unit 7 members would receive the higher GSI in 2022‑23. The four GSIs provided by the proposed agreement would compound to a 10.4 percent pay increase for non-POFF employees and 12 percent for POFF employees.

Two Opportunities for Director of Finance to Reopen Agreement. The agreement would give the Director of Finance the sole discretion to determine if the Governor’s 2021‑22 or 2022‑23 May Revisions project sufficient revenues “to fully fund existing statutory and constitutional obligations, existing fiscal policy, and the costs of providing these pay increases to all eligible employees.” If the Director of Finance determines revenues are insufficient, the agreement can be reopened. (This conceptual approach is similar to a number of provisions in the 2019‑20 budget package, which we discuss in our report The 2019‑20 Budget: Overview of the California Spending Plan.) If the Director of Finance reopens the agreement pursuant to this provision, the agreement would be controlling unless the parties agree to change the agreement. This means that the July 1, 2021 and 2022 pay increase would go into effect unless the parties agree otherwise or the Legislature does not appropriate funds for the pay increases.

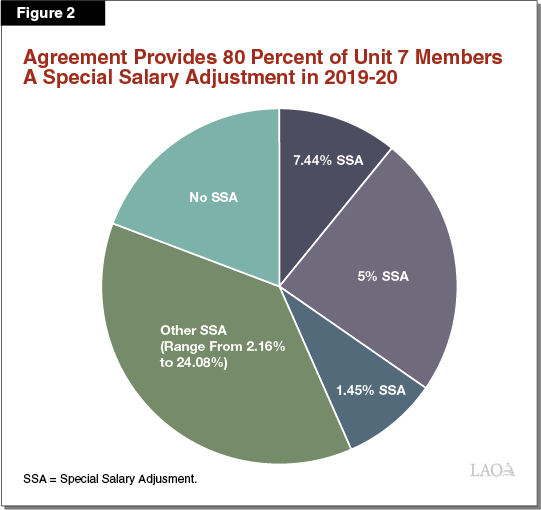

Classification-Specific Salary Increases to 80 Percent of Bargaining Unit. The agreement would provide 58 classifications Special Salary Adjustments (SSAs). In total, as shown in Figure 2, about 80 percent of the bargaining unit would receive SSAs in addition to the GSIs described above. The SSAs range from 1.45 percent to 24.08 percent, depending on the classification. After accounting for the SSAs and GSIs, the average Unit 7 member would receive about a 15 percent pay increase over the course of the agreement.

Criminalist Classifications Receive Two SSAs. Within the forensic science technicians occupation, two classifications would receive two SSAs. Specifically, the criminalist classifications (criminalist and senior criminalist) would receive a 5 percent SSA in 2019‑20 and an additional 5 percent SSA in 2020‑21—these pay increases would be in addition to the GSIs. These are the only two classifications that would receive more than one SSA under the agreement. These classifications work for the Department of Justice (DOJ) and are funded by the DNA Identification Fund we discuss below. During past budget discussions, the administration has indicated that it is difficult for the state to retain criminalists at the state’s forensic laboratories; however, this specific concern was not identified by the administration when we asked about the proposed pay increases in the agreement.

Pay Increases for Specified Activities. The agreement provides pay increases to employees for performing specific tasks during their work. These pay differentials are summarized in the administration’s summary of the agreement. One of these pay differentials that we discuss in greater detail below is a differential provided to employees who are assigned as “canine handlers.” Specifically, the agreement would establish a 5 percent pay differential for a canine handler at the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) and specifies the level of care that the handler must provide the canine.

Employee Health Benefits

Increases State Costs for Health Benefits. The state contributes a flat dollar amount to Unit 7 members’ health benefits that was last adjusted in January 2019. The proposed agreement would adjust the amount of money the state pays towards these benefits in January of 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023. For the term of the agreement, the state’s contribution would be adjusted so that the state pays 80 percent of an average of California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) premium costs plus up to 80 percent of average CalPERS premium costs for enrolled family members—referred to as the “80/80 formula.” The state’s contributions would not be increased after January 2023 unless agreed to in a future agreement.

Pension

Increased Employee Contributions Towards Pensions. The agreement would increase the amount of money that employees contribute towards their pension benefits. Specifically, (1) employees in the POFF retirement tier would increase their contributions from 13 percent of pay to 14 percent of pay in 2022‑23 and to 15 percent of pay in 2023‑24, (2) employees in the State Safety retirement tier would increase their contributions from 11 percent of pay to 11.5 percent of pay in 2023‑24, and (3) employees in the State Miscellaneous retirement tier would increase their contributions from 8 percent of pay to 8.5 percent of pay in 2023‑24. These increased employee contribution rates would reduce the state’s contribution rates to pensions.

Provisions From Current Agreement Removed

Reduction of Eligible Classifications for Recruitment/Retention Differential. The current agreement provides specified classifications at the Department of State Parks and Recreation and the Department of Fish and Wildlife a recruitment and retention differential of $175 per pay period. The proposed agreement would—effective July 1, 2019—remove five classifications from this differential.

Pay Differential for Investigators. The current agreement provides investigators at the top step of salary range C of the classification who work at the Department of Insurance and the Department of Consumer Affairs a 7.44 percent pay differential. The proposed agreement removes this provision.

Furlough Protection. The current Unit 7 agreement specifies that the state could not implement a furlough in the first year of the agreement (2016‑17) and that any furloughs in subsequent years would have had to be authorized by the Legislature. The proposed agreement removes this provision.

LAO Assessment

Overall Assessment

Three-Year Duration Limits Legislative Flexibility. We recommend that the Legislature only approve agreements with terms of one or two years. This recommendation is intended to maintain legislative flexibility. Given the state’s volatile revenue structure, anticipating whether the budget could support particular pay raises more than two years in advance is very difficult. Moreover, anticipating the appropriate level of salary increases in the future is difficult given economic and labor conditions could be different than today. Although the proposed agreement does allow for the Director of Finance to reopen negotiations in the event of insufficient revenues, the pay increases would not automatically be repealed. Further, in exchange for delaying or eliminating the scheduled pay increases, employees likely would expect some form of offsetting compensation with unknown fiscal implications for the state.

Legislature Has Ultimate Authority to Determine if There Are Sufficient Revenues in Any Given Year to Fund an Agreement. The agreement gives the Director of Finance the authority to reopen negotiations on two occasions, depending on the Director’s assessment of the state’s budget condition. The agreement frames this authority as being the director’s “sole discretion.” For clarification, under the Ralph C. Dills Act and the Legislature’s constitutional power of the purse, the Legislature always has the authority to appropriate in the annual budget act an amount of money that is less (or more) than what would be necessary to fund a scheduled pay increase established under a ratified agreement. If the Legislature determines that there are insufficient revenues in a given year, the Legislature may choose not to appropriate funds for a pay increase scheduled under a ratified agreement. In this case, the pay increase may not go into effect and either the union or Governor may reopen negotiations on all or part of the labor agreement.

Administration’s Fiscal Estimate

Agreement Would Increase Ongoing Annual Costs by $127 Million ($40 Million General Fund) by 2023‑24. As shown in Figure 3, the administration estimates that the proposed agreement would increase state annual costs by more than $127 million by 2023‑24. The actual costs in the out years could be higher or lower, depending on increases to CalPERS health premiums and pension contribution rates.

Figure 3

Administration’s Estimates of Proposed Unit 7 Agreement

(In Millions)

|

Proposal |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

|||||||||

|

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

|||||

|

Various Special Salary Adjustments |

$10.4 |

$35.2 |

$11.1 |

$37.0 |

$11.1 |

$37.0 |

$11.1 |

$37.0 |

$11.1 |

$37.0 |

||||

|

Changes to various pay differentials and other provisionsa |

‑0.1 |

‑0.8 |

‑0.1 |

‑0.8 |

‑0.1 |

‑0.8 |

‑0.1 |

‑0.8 |

‑0.1 |

‑0.8 |

||||

|

General Salary Increases |

6.1 |

20.5 |

11.9 |

39.7 |

17.8 |

59.5 |

25.5 |

81.6 |

25.5 |

81.6 |

||||

|

Health benefits |

0.5 |

1.7 |

1.5 |

5.1 |

2.7 |

8.9 |

3.9 |

13.0 |

4.4 |

14.7 |

||||

|

Increased employee pension contributionsa |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

‑0.6 |

‑2.0 |

‑1.6 |

‑5.2 |

||||

|

Totals |

$16.9 |

$56.6 |

$24.4 |

$81.0 |

$31.4 |

$104.5 |

$39.7 |

$128.7 |

$39.3 |

$127.3 |

||||

|

aThe administration assumes that at least a portion of these costs/savings will not affect state appropriations. |

||||||||||||||

Increases in Overtime Costs Resulting From Salary Increases Not Reflected. The administration’s fiscal estimates do not include increased overtime costs resulting from higher salaries under the agreement. Overtime is a significant component of Unit 7 members’ compensation. In 2018, Unit 7 members received a total of $53 million in overtime—averaging about $9,000 per employee who earned overtime. We estimate that the scheduled pay increases could result in Unit 7 overtime costs increasing by more than $7 million. The administration assumes that increased overtime costs resulting from the agreement would be paid from existing departmental resources, meaning that departments would have to redirect funds that the Legislature has appropriated for other purposes.

Costs to Extend Provisions to Excluded Employees. When rank-and-file pay increases faster than managerial pay, “salary compaction” can result. Salary compaction can be a problem when the differential between management and rank-and-file is too small to create an incentive for employees to accept the additional responsibilities of being a manager. Consequently, the administration often provides compensation increases to managerial employees that are similar to those received by rank-and-file employees. Although the administration has significant authority to establish compensation levels for employees excluded by the collective bargaining process, these compensation levels are subject to legislative appropriation. The estimates above do not include any costs resulting from the state extending provisions of the agreement to excluded employees associated with Unit 7. We estimate that extending a comparable increase in compensation to Unit 7 supervisors and managers could increase state annual costs by tens of millions of dollars—likely not to exceed $50 million—by 2023‑24. About 70 percent of these increased costs would be paid from funds other than the General Fund.

Pay Increases

State Law Requires Compensation Study. Section 19826 of the Government Code specifies that the California Department of Human Resources (CalHR) shall establish salary ranges for state classifications “based on the principle that like salaries shall be paid for comparable duties and responsibilities.” Further, the law requires that—when establishing or changing pay ranges—“consideration shall be given to the prevailing rates for comparable service in other public employment and in private business.” The law requires that at least six months before a labor agreement expires, CalHR submit to the union that represents the affected employees and the Legislature “a report containing the department’s findings relating to the salaries of employees in comparable occupations in private industry and other governmental entities.”

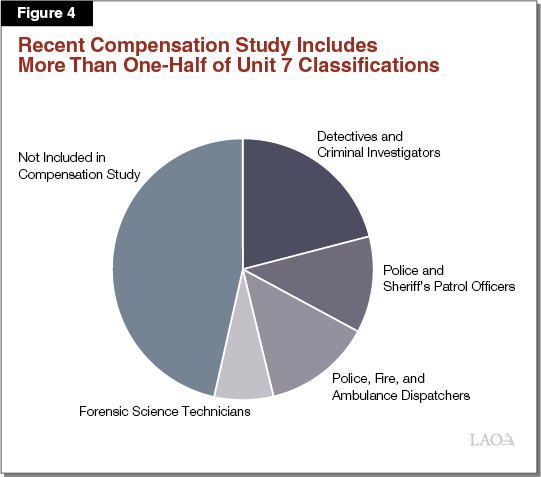

The administration released a compensation study for Unit 7 pursuant to Section 19826 in January 2019. The compensation study uses survey data from 2017 to compare state wages and total compensation with comparable employee compensation offered by local government, federal government, and (when possible) private sector employers. The study compares occupation groups—not classifications. The study looked at the compensation levels of four occupation groups within Bargaining Unit 7: (1) detectives and criminal investigators; (2) police and sheriff’s patrol officers; (3) police, fire, and ambulance dispatchers; and (4) forensic technicians. Based on job functions, CalHR organized relevant Unit 7 classifications into one of these four occupations. Within these four occupation groups, CalHR was able to evaluate the compensation of 46 Unit 7 classifications—representing about 54 percent of Unit 7 full-time employees, as shown in Figure 4.

Compensation Study Identified Two Unit 7 Occupations Compensated Below Market . . . Through the 2019 compensation study, CalHR found that two Unit 7 occupation groups receive total compensation that is below market. Specifically, CalHR found that detectives and criminal investigators receive total compensation that is 6 percent below the market average (19 percent below local government employers and 3 percent above federal government counterparts) and that police and sheriff’s patrol officers receive total compensation that is 35 percent below market average (36 percent below local government employers and 21 percent above federal government counterparts). The previous compensation study also found that these two occupation groups were compensated below market in 2014. In the case of detective and criminal investigators, CalHR found that the state’s lag in total compensation has improved from being 15 percent below market in 2014 to being 6 percent below market in 2017. In the case of police and sheriff’s patrol officers, CalHR found that the state’s lag in total compensation has held steady at about 35 percent in the same time period.

. . . And Two Compensated Above Market. CalHR found that two Unit 7 occupation groups receive total compensation that is above market. Specifically, CalHR found that police, fire, and ambulance dispatchers receive total compensation that is 10 percent above the market average (9 percent above local government employers and 34 percent above private sector employers) and that forensic science technicians receive total compensation that is 7.4 percent above local government employers. The previous compensation study also found that these two occupation groups were compensated above market. CalHR found that the state’s lead in total compensation for employees in these occupation groups has grown for both occupations between 2014 and 2017.

Significant Regional Differences Found in Compensation Study. The cost of living in California varies significantly by region. Employees in the same occupation often earn higher levels of compensation in higher cost of living regions in the state. The state employs people in each county with about two-thirds of the state workforce in a county other than the County of Sacramento. In many cases, the state employs people in the same classification in both high and low cost of living regions of the state. As a result, the state has (among other considerations) two competing priorities when determining an appropriate level of compensation for a classification. One priority is for the state to be a competitive employer in a region’s labor market by offering a compensation package that allows the state to recruit and retain employees. The second competing priority is to limit the amount of regional difference within a classification in order to prevent state employees from consistently transferring to higher paid regions of the state. As Figure 5 shows, the CalHR compensation study illustrates the state’s challenge to compete in multiple regional labor markets across the state by the fact that CalHR found that the state’s lead and lag in total compensation varies significantly across the state.

Figure 5

State Lag (‑) or Lead (+) in Total Compensation Varies Significantly in

Labor Markets Across State

|

Police and Sheriff’s Patrol Officers |

Detectives and Criminal Investigators |

Forensic Science Technicians |

Police, Fire, and Ambulance Dispatchers |

|

|

Sacramento County |

‑29% |

‑25% |

‑9% |

11% |

|

San Francisco County |

‑51 |

‑32 |

9 |

‑10 |

|

Los Angeles County |

‑38 |

‑26 |

3 |

9 |

|

San Diego County |

‑12 |

7 |

12 |

13 |

|

Other Counties |

2 |

16 |

41 |

25 |

|

Statewide |

‑35 |

‑6 |

7 |

10 |

|

“+” = Above Market and “‑” = Below Market. |

||||

Justification of Proposed SSAs Not Necessarily Rooted in Compensation Study Findings. Based strictly on the compensation study, the clearest case for large pay increases would be for classifications in the two occupation groups that were found to be below market. The administration states, however, that the proposed SSAs were based on addressing various concerns mutually agreed upon by both management and CSLEA at the bargaining table rather than the compensation study. Figure 6 shows the weighted average of the SSAs proposed for the four occupations included in the compensation study—these pay increases are in addition to the GSIs discussed above. Of the occupations included in the compensation study, the two occupations found to be compensated above market would receive a pay increase that is larger than that received by classifications in the police and sheriff’s patrol officers occupation—which CalHR found to be 35 percent below market statewide.

Figure 6

Proposed Special Salary Adjustments (SSAs) Vary by Occupation

|

Occupation |

Average |

2017 Statewide Total Compensation |

|

Detectives and Criminal Investigators |

8.5% |

‑6% |

|

Forensic Science Technicians |

7.5 |

7 |

|

Police, Fire, and Ambulance Dispatchers |

5.0 |

10 |

|

Police and Sheriffs Patrol Officers |

4.2 |

‑35 |

|

Other occupation not included in CalHR study |

2.3 |

N/A |

|

Bargaining Unit 7 |

4.6 |

N/A |

|

CalHR = California Department of Human Resources. |

||

Canine Unit and DDS. Although a small budgetary effect, the agreement would establish a canine unit at DDS to conduct searches for illicit drugs at the Porterville Developmental Center’s Secure Treatment Area. The Legislature has never before approved a canine unit at DDS. The creation of a canine unit at a department is something that typically we would expect to be considered by the Legislature through the Budget Change Proposal process rather than through a labor agreement. We raise no concerns with the proposal but provide information here for the legislative budget committees.

In the past, DDS has used Department of State Hospitals canine units to perform these types of searches. The department indicates that having a canine unit on site will allow for the department to better ensure the health and safety of all individuals at the site, many of whom take legally prescribed drugs that could adversely interact with illicit drugs. The department reports that the canine cost about $20,000—including training the canine and the handler and making minor vehicle modifications to allow for safe transport of the canine—and that the annual cost to care for the canine will be about $1,400. The department plans to pay for these costs using existing resources but reports that it will not need to hold any positions vacant to redirect resources. The pay differential provided to the canine handler would be $291 based on the maximum salary for a peace officer—totaling to a state cost of about $5,000 after accounting for salary-driven benefit costs. CalHR’s fiscal estimates assume that the department would receive an augmentation to pay for the pay differential.

DNA Identification Fund. The state’s DNA Identification Fund receives the state’s share of certain assessments charged to individuals convicted of criminal offenses (including traffic violations). This fund primarily supports DOJ’s Bureau of Forensic Services. In recent years, this fund has faced insolvency due to a decline in the total amount of criminal fine and fee revenue collected annually. This insolvency has been addressed in various ways—such as through one-time General Fund backfills that have been provided annually since 2016‑17. For example, the 2019‑20 budget includes a one-time $25 million General Fund backfill. Because of the continued insolvency of this fund, future increases in costs greater than what currently is assumed could increase expenditure pressure on the General Fund absent any future legislative or DOJ action. Additionally, as part of the 2019‑20 budget package, the Legislature directed DOJ to submit a report by January 1, 2020, which among other things would require DOJ to identify what operational or other changes would be needed for its Bureau of Forensic Services to operate within the revenues available in the DNA Identification Fund or other non-General Fund resources (such as fees for provided services). As part of this report, the administration should report to the Legislature the effects of any compensation increases—including the two SSAs provided to criminalists funded by this fund—on the fund’s condition and its ability to be sustained without General Fund backfill.

Increased Employee Pension Contributions: Pressure to Increase Salary

As we have indicated in past analyses, increasing employee contributions to prefund retirement benefits creates pressure for the state to provide offsetting salary increases to employees. Typically, attributing what share of a proposed salary increase is in exchange for an increased employee contribution to a retirement benefit is difficult. In this case, however, the agreement clearly would provide employees GSIs to fully offset the increased employee contributions. We come to this conclusion based on the GSI provided to employees in 2022‑23. The 2022‑23 GSI size depends on whether an employee is in the POFF retirement category or another retirement category. Specifically, peace officers receive a GSI that is 1.5 percent greater than that provided to other employees. The agreement also would increase the amount of money that employees contribute towards their pensions such that peace officers’ contribution increases by 1.5 percent of pay more than other employees’ contributions increase. The administration confirmed that the larger GSI is commensurate to the higher retirement contribution. Further, the union’s summary of the agreement asserts that the difference between the peace officer and other employees’ GSIs is “to offset the future increases to retirement contributions.” In this case, the proposed salary increases clearly are a one-for-one offset to the increased employees’ contributions towards their pensions.

Maintaining the state’s current share of the normal cost would be less expensive than providing a salary increase to offset higher employee contributions. This is because every additional $1 of salary increases the state’s costs by more than $1 to pay for salary and salary-driven benefit costs (costs that are determined as a percentage of pay). For example, a $1 salary increase to a peace officer increases the state’s costs by about $1.50. Fully offsetting the increased employee contributions—as this agreement provides—means that for every $1 the state’s pension contributions are reduced, the state’s payroll costs increase about $1.50.

Other Considerations

Consider Unit 7 Agreement With Other Agreements That Come in. In the remaining weeks of session, the Legislature could receive proposed labor agreements for more than one-half of the state’s rank-and-file workforce. Specifically, we understand that the administration hopes to submit an agreement with the nine bargaining units represented by Service Employees International Union, Local 1000 (Local 1000). In addition, the Legislature could receive proposed labor agreements with four other bargaining units with expired agreements—Bargaining Units 2 (Attorneys), 5, (Highway Patrol), 13 (Stationary Engineers), and 18 (Psychiatric Technicians). Any bargaining agreements with these 13 bargaining units likely will have significant short- and long-term budgetary effects for the state’s General Fund and special funds. We recommend that the Legislature defer action on the Unit 7 agreement until it can consider the agreement with all the other units that may come in between now and the end of session. Considering all 14 proposed agreements simultaneously would allow the Legislature to comprehensively evaluate how the agreements fit into the Legislature’s current-year and multiyear budget framework. We highlight issues for the Legislature to consider in that evaluation below.

Potential Increased Costs for Challenged Special Funds. The state’s primary operating fund is the General Fund. In addition to the General Fund, the state has hundreds of special funds that serve as the operational funding source for programs with specific purposes. The primary funding source for special funds often are fees for service. Some special funds operate at a surplus while others have significant challenges due to some combination of declining revenues and increasing expenditures. For many departments, the largest category of expenditure is related to employee compensation. For departments funded by a challenged special fund, growth in employee compensation costs beyond what currently is projected can further weaken the special fund’s condition. At least one of these funds—the Motor Vehicle Account (MVA)—could be affected significantly by the other forthcoming agreements.

MVA and Collective Bargaining. The MVA receives revenues from vehicle registration and other fees to support the state administration and enforcement of vehicle-related laws. This account primarily supports the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) and California Highway Patrol (CHP) operations and facilities. In recent years, the MVA has struggled to remain solvent due to expenditures on occasion growing faster than revenues. In order to help address the MVA’s solvency, as well as increased MVA expenditures in the current year (such as a net increase of $242 million for DMV to process federally compliant driver licenses and identification cards), the 2019‑20 budget includes various actions intended to benefit the MVA in the near term (such as suspending a transfer of revenues from the MVA to the General Fund and delaying facility projects). Future increases in costs for DMV and CHP employees above what currently is assumed would increase expenditure pressures upon the MVA absent any future legislative or departmental action.

Units 5 and 7, employees represented by Local 1000, and related managers and supervisors constitute virtually all of the employees at DMV and CHP. The actions taken as part of the 2019‑20 budget are based on the administration’s MVA fund condition projections that assume employee compensation at CHP grows by 3 percent each year between 2020‑21 and 2023‑24 and that employee compensation at DMV grows by 2 percent each year during the same period. These assumed compensation increases include salary, pension, and growth in other components of compensation. If the Local 1000 and Unit 5 agreements contain similar levels of compensation growth as is provided by the proposed Unit 7 agreement, the Legislature might have to revisit its recent actions to maintain MVA solvency.

Legislature Likely Will Not Have A Compensation Study for Local 1000. As discussed earlier, state law requires the administration to submit a compensation study to the Legislature six months before an agreement is scheduled to expire. The current agreement with Local 1000 will expire in January. The administration informs us that it recently received the data necessary to conduct the Local 1000 compensation study and that the report likely will be released in the fall. Assuming the administration submits a Local 1000 agreement to the Legislature before the end of session, this means that the Legislature will be asked to ratify an agreement that affects the compensation of about one-half of the state’s rank-and-file workforce without a sense of how the state’s compensation for these employees compare with compensation provided by other employers to similar employees. The last compensation study for Local 1000 classifications was released January 2016 (using 2014 data) and found that some of the occupations represented by the union were compensated above market while others were below market.