December 18, 2019

The 2020-21 Budget:

Analyzing UC and CSU Cost Pressures

Executive Summary

Report Analyzes Cost Pressures at UC and CSU. California operates two public university systems: (1) the University of California (UC), consisting of 10 campuses, and (2) the California State University (CSU), consisting of 23 campuses. Compared with many other areas of the state budget, the Legislature has considerable flexibility through the annual budget process to decide which university costs to support. Despite this greater flexibility, the Legislature faces many pressures to increase funding for UC and CSU in 2020‑21. This report examines these university cost pressures, assesses the state’s capacity to fund some of them, and identifies options for expanding budget capacity to fund additional cost pressures.

Cost Pressures

Employee Salary Increases Likely to Remain Key Cost Pressure. Existing law grants both university systems authority to negotiate compensation levels for their employees. Since 2013‑14, both systems have provided annual salary increases, generally ranging from 2 percent to 5 percent depending on the employee group. Because contracts are not in place for most university employee groups in 2020‑21, salary increases will likely be a key issue facing the Legislature in the upcoming budget. We estimate the cost of a 1 percent salary increase to be around $45 million at each segment in 2020‑21.

Employee Benefit Costs Continue to Rise, Universities Have Notable Unfunded Liabilities. Like most government employees in California, university employees receive subsidized health care while they are employed, and they receive both pensions and subsidized health care when they retire. These benefit costs are among the fastest growing cost pressures at UC and CSU. We estimate benefit costs across both university segments will increase by around $195 million in 2020‑21. In addition, both university systems have billions of dollars in unfunded pension and retiree health liabilities resulting from underfunding earned benefits in previous years.

Universities Have Large Facility Maintenance Backlogs. Like most state agencies, UC and CSU dedicate a portion of their core budgets for facility maintenance, such as keeping electrical and plumbing systems in working order. As their spending on maintenance has tended to be insufficient over the years, campuses have accrued billions of dollars in unaddressed facility maintenance and seismic renovation projects. These backlogs create significant cost pressure for the Legislature in the budget year and future years. To better guide state funding decisions, the Legislature recently directed the universities to develop long‑term plans to address their backlogs. The Legislature is to receive CSU’s report by January 2020 and UC’s report by January 2021.

Some Pressure to Expand Enrollment but No Underlying Demographic Growth. When weighing enrollment growth decisions in the upcoming budget, the Legislature faces a number of key factors. First, the number of high school graduates is projected to decline slightly in the upcoming year. Both segments are also drawing from larger pools of high school students than expected under state policy. These factors potentially suggest further enrollment growth is not warranted in 2020‑21. On the other hand, the Legislature may wish to grow enrollment to improve access at high demand campuses. Based on the state’s existing per‑student funding rates, we estimate growing enrollment by an additional 1 percent would cost the state around $40 million at UC and $45 million at CSU.

Legislature Likely to Face Many Other University Cost Pressures. In recent years, the Legislature has considered various initiatives that change the level or scope of university services. These initiatives have included: (1) increasing the number of tenured/tenure‑track faculty; (2) improving graduation rates at CSU; (3) limiting nonresident enrollment at UC; (4) expanding student food, housing, and mental health programs; and (5) establishing new academic programs and campuses. In 2020‑21, the Legislature very likely will continue to face pressure for additional spending in each of these areas.

Planning Issues

State Budget Has Capacity to Fund Some University Cost Pressures. In The 2020‑21 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook (fiscal outlook), we calculate the state’s budget capacity for the coming year. In making our calculations, we first assume the state maintains existing services, as adjusted for inflation. For the universities specifically, we assume the state covers salary, pension, health benefits, and debt service cost increases. After accounting for these types of cost pressures, we estimate the state would have a $7 billion surplus. Given certain risks to the General Fund, we recommend the Legislature limit new ongoing spending commitments across all areas of the state budget to around $1 billion. In the case of the universities, any remaining ongoing pressures (such as enrollment growth, expansion of services, and new programs or campuses) likely would be up for legislative consideration for a portion of this $1 billion. After making new ongoing commitments, the remainder of the state surplus would be available for one‑time commitments, accelerated debt payments, or larger state reserves. If the Legislature would like to direct some of the remaining surplus to the universities, we encourage it to give high priority to addressing the universities’ unfunded liabilities and facility maintenance backlogs (including seismic renovations). Addressing these liabilities now would reduce the burden on future generations and improve the fiscal health of the state and universities.

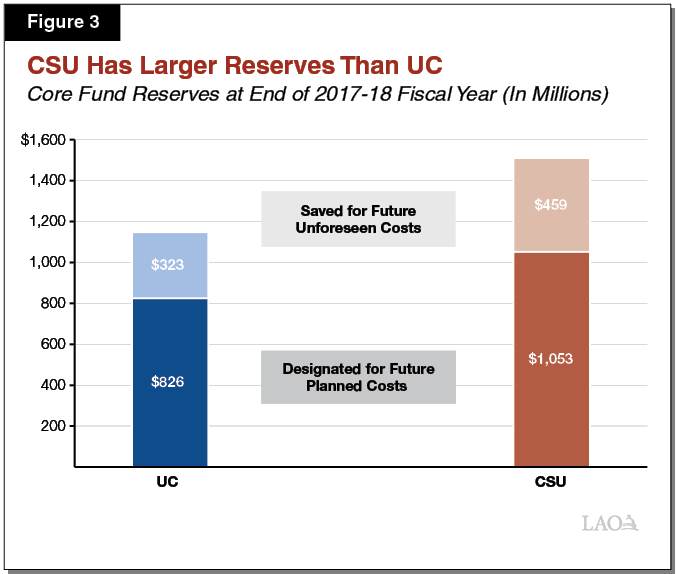

Legislature Has Some University Options for Expanding Budget Capacity. Our fiscal outlook assumes the state covers inflationary cost increases, with no increases in tuition for resident students. However, one key option available to the Legislature for covering additional cost pressures is to share ongoing university cost increases with students through a tuition increase. We estimate that every 1 percent increase in tuition raises associated net revenue by about $15 million at UC and $10 million at CSU. Another option would be to work with the universities to pursue efficiencies in their operations and facility utilization. The amount of freed‑up funding that could be redirected would depend upon the specific efficiencies pursued, with some options creating budget‑year savings but others not yielding savings until later years. Another option would be to factor campuses’ reserves into state budget decisions. The Legislature could be strategic in the use of these reserves—using them to protect ongoing university operations during an economic downturn or using them to address key one‑time priorities, such as deferred maintenance, in the budget year. Each of the university systems potentially has hundreds of millions of dollars in reserves that are available for such spending purposes.

Introduction

The Universities Are a Key Part of State’s Discretionary Budget. California operates two public university systems: (1) the University of California (UC), consisting of 10 campuses, and (2) the California State University (CSU), consisting of 23 campuses. Neither the State Constitution nor federal law requires the state to spend a certain amount on UC and CSU. Furthermore, the Legislature has enacted few statutes to guide its decisions on how much General Fund to allocate annually to the universities. Because of the lack of constitutional or statutory requirements, the Legislature has considerable flexibility through the annual budget process to decide which university costs to support. For few other major state programs (most notably, the court system) does the Legislature have a comparable amount of flexibility. Budgeting for the universities also differs from many other areas in that UC and CSU have a considerable amount of nongovernmental funding available to them—most notably through the levying of student tuition charges.

Report Examines Key UC and CSU Cost Pressures. As the Legislature begins to develop its 2020‑21 budget, it faces many pressures to increase General Fund support for UC and CSU. These cost pressures range from covering rising health care costs (somewhat outside the universities’ control) to raising employee salaries (largely within the universities’ control). The pressures also range from addressing existing obligations (including unfunded pension liabilities and facility maintenance backlogs) to creating new ones (by funding enrollment growth, expanding services, offering new types of services, or building new campuses). Over the coming months, many groups—from faculty and student groups to groups with regional or other specific interests—likely will encourage the Legislature to increase state support in one or more of these areas. To aid the Legislature in considering these requests and building an overall budget plan, this report describes and analyzes these cost pressures. The report begins with background on UC’s and CSU’s budgets, then examines key cost pressures. It concludes by discussing several university‑related planning issues the Legislature will face in the coming budget session.

Overview of University Budgets

In this part of the report, we provide background on each segment’s core funding, spending, and reserves.

Funding

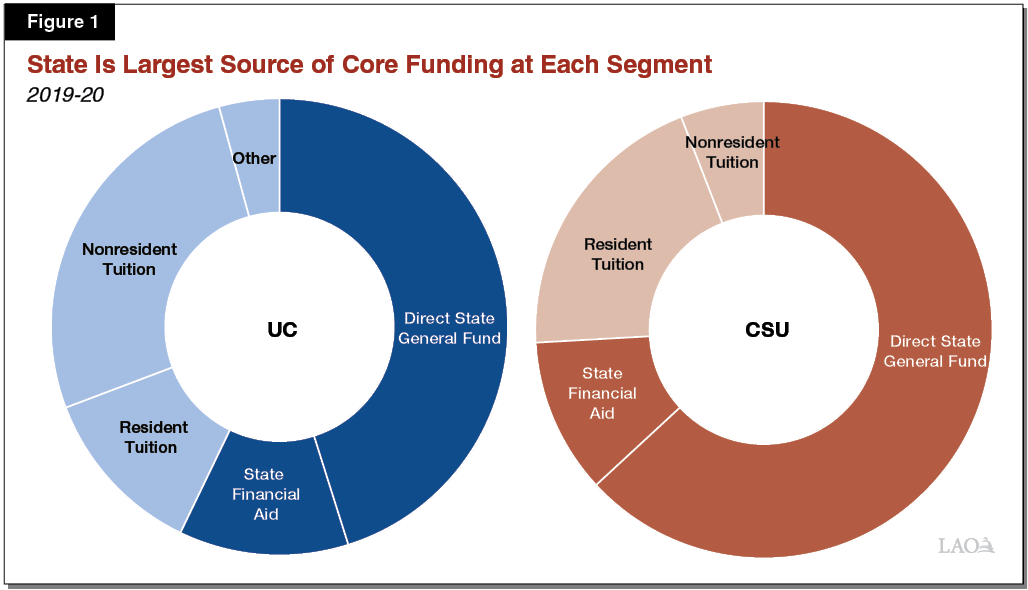

Core Funds Support Each Segment’s Academic Mission. Core funding consists of state General Fund, student tuition revenue, and several other smaller fund sources. Core funding supports the universities’ academic functions, including undergraduate and graduate instruction, academic support services (such as tutoring), and related administrative costs. Core funding also supports various research and outreach initiatives. In 2019‑20, core funding represents around 70 percent of all funding at CSU and 25 percent of funding at UC. The universities’ remaining fund sources support various nonacademic purposes, such as on‑campus housing and UC’s medical centers. Throughout the remainder of this report, we focus on core funds and associated spending.

State Is the Largest Source of Core Funding. State General Fund comprises about 60 percent of core funding for UC and 75 percent for CSU (Figure 1). These amounts include direct General Fund appropriations to the universities to cover operating costs. They also include support for the Cal Grant program, which covers the cost of tuition at UC and CSU for eligible students with financial need. (Students are considered to have financial need when the cost to attend college exceeds the amount their households can contribute, as calculated by certain federal formulas.) The remaining core funding comes from student tuition charges and, at UC, a few smaller fund sources (such as overhead allowances on federal research grants). Around 40 percent of resident students—generally those without financial need—pay tuition. Nonresident students, who are generally not eligible for state financial aid, also pay tuition (at a higher rate than resident students). The share of core funding coming from nonresident tuition is larger at UC than at CSU, as nonresidents comprise a larger share of overall enrollment at UC and pay higher tuition charges.

State and Segments Determine Level of Core Funding. Each year, the Legislature appropriates direct General Fund support to UC and CSU as part of the annual budget act. The Legislature does not directly set student tuition charges. Existing law grants this authority to the systems’ governing boards—the UC Board of Regents and the CSU Board of Trustees. Despite different entities controlling state General Fund and student tuition decisions, in practice these decisions are often connected. For example, in many years the governing boards have held tuition flat in response to increases in state funding and other signals from the Legislature. In other years, the boards have adopted tuition hikes in response to reductions in state funding.

Spending

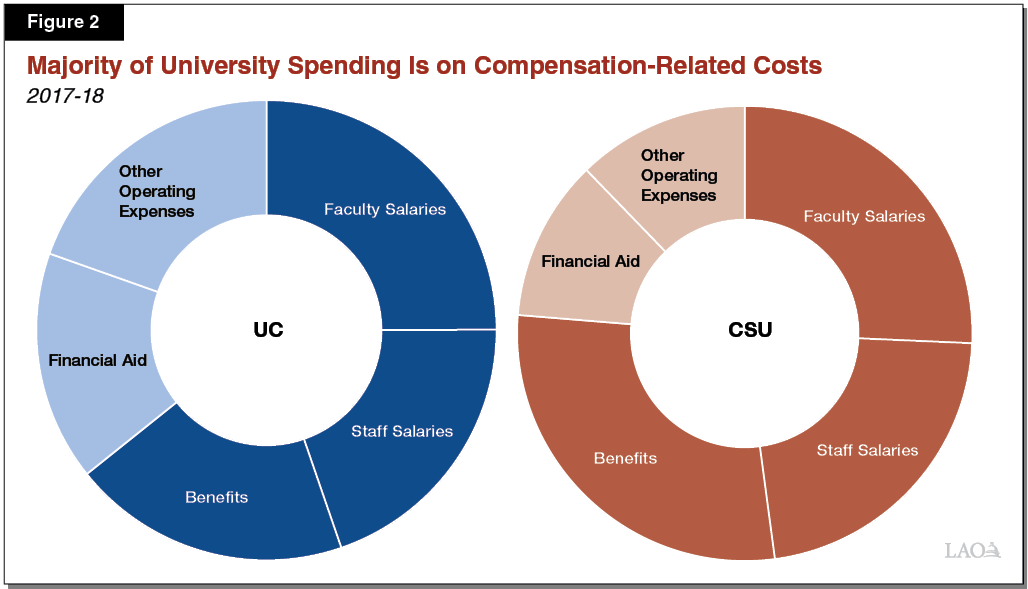

Majority of Core Spending Is on Employee Compensation. As Figure 2 shows, 76 percent of CSU spending and 64 percent of UC spending is for employee salaries and benefits. At both segments, benefits include pension contributions, employee health care, and retiree health care. The next largest component of spending at both segments is on their respective financial aid programs. (Both UC and CSU fund financial aid programs that help financially needy students not receiving state Cal Grants or, in the case of UC, supplement Cal Grant aid.) Another portion of core spending is on various other operating expenses, including facility maintenance, annual facility debt service payments, equipment, and utilities.

Universities Have Considerable Control Over Spending. For employee salaries—almost half of each segment’s core spending—state law grants the governing boards authority to determine salary levels, set staffing levels, and approve collective bargaining agreements with unions. For benefits, UC has somewhat greater control over costs than CSU. UC operates its own pension, employee health, and retiree health programs, with benefits in each of these areas determined by the Board of Regents. CSU, by contrast, participates in state‑administrated pension and health care programs and provides benefits that are established in state law. The California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) makes decisions that affect CSU spending in these areas.

Reserves

Both Systems Maintain Reserves. State law is silent on whether the universities should build reserves, the purpose of those reserves, or the appropriate levels of those reserves. The universities, however, have developed reserve policies, which generally designate reserves for a couple of main purposes. The systems maintain reserves intended to cover large, planned future costs, such as renovating a building, purchasing equipment, or launching a new academic program. The systems also maintain reserves to help them respond to unforeseen events, such an economic recession or natural catastrophe.

Universities Each Have Over $1 Billion in Core Reserves. At the end of 2017‑18, CSU held $1.5 billion in core reserves whereas UC held $1.1 billion. CSU’s core reserve level was equivalent to about 3 months of operating expenses, whereas UC’s level was equivalent to about 1.5 months. As Figure 3 shows, the universities have designated most reserve funds for planned future costs. They have each kept about 30 percent of their reserves available to respond to future risks and uncertainties.

Key Cost Pressures

In this part of the report, we analyze four key cost drivers affecting the universities’ core budgets: (1) compensation, (2) academic facilities and infrastructure, (3) student enrollment growth, and (4) various other recent priorities of the Legislature and universities. The first two of these pressures generally are costs the state faces to maintain the existing level of services at campuses and address long‑term liabilities. The latter two cost pressures are costs the state faces to expand the level or scope of university services. For each cost driver, we provide background; discuss past spending trend; and, where possible, estimate costs for 2020‑21.

Compensation

In this section, we analyze three key compensation‑related costs pressures: (1) employee salaries, (2) pension contributions, and (3) health benefits for employees and retirees.

Employee Salaries

Collective Bargaining More Notable Factor Driving Salaries at CSU Than UC. CSU employs about 50,000 faculty and staff. Of these employees, 90 percent—including all faculty and most staff—are represented by 1 of 13 bargaining units. Represented employees receive salary increases according to collective bargaining agreements negotiated with the Chancellor’s Office and approved by the Board of Trustees. These bargaining agreements often indirectly drive salary increases for the remaining 10 percent of CSU employees (primarily consisting of managers and executives) who are not represented by a union. This is because the CSU Chancellor’s Office typically chooses to keep salary growth for these employees at pace with represented employee groups. Compared to CSU, collective bargaining is a less salient factor for UC salaries, as only one‑third of its more than 40,000 core‑funded employees are represented by a union. For the remaining two‑thirds of employees—which includes all tenured and tenure‑track faculty and most staff—the UC President usually makes decisions regarding salary increases.

Universities Have Provided Salary Increases the Past Several Years. After not providing general salary increases for most employee groups from 2008‑09 through 2012‑13, both systems have approved salary increases every year since 2013‑14 (Figure 4). Within each system, salary increases have tended to be similar across employee groups, especially when viewed across the entire seven‑year period (with some groups getting larger increases one year but then smaller increases the next year). The salary increases have tended to be somewhat larger at CSU than UC. At both segments, salary increases have tended to roughly equal or outpace inflation. (From 2013‑14 through 2019‑20, consumer prices in California grew an average annual rate of 2.8 percent.)

Figure 4

University Employees Have Had Salary Increases in Recent Years

General Salary Increases by Employee Group

|

2013‑14 |

2014‑15 |

2015‑16 |

2016‑17 |

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

|

|

UC |

|||||||

|

Faculty |

2% |

3% |

3%a |

3%a |

3%a |

3%a |

3%a |

|

Nonrepresented staff |

3 |

3 |

3a |

3a |

3a |

3a |

3a |

|

Represented employees |

0‑4.5 |

2‑4.8 |

2‑4 |

2‑8.4 |

0‑3 |

0‑7b |

0‑3b |

|

CSU |

|||||||

|

Faculty |

1.3% |

3% |

5% |

2% |

4.5% |

3.5% |

2.5% |

|

Represented support staff |

1.3 |

3 |

2 |

5 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

|

Other staffc |

0‑4.6 |

2‑3 |

2‑2.9 |

2‑5 |

2.2‑4 |

3‑4 |

3‑4 |

|

aIncreases were distributed based on merit. bContracts for two bargaining units are still under negotiation. cConsists of other represented and nonrepresented staff. |

|||||||

Likely Pressure to Increase Salaries in 2020‑21. At both systems, employee salary increases in 2020‑21 are uncertain. At CSU, virtually all bargaining contracts expire at the end of 2019‑20. The Chancellor’s Office is currently negotiating contracts for the budget year. At UC, the UC President has not yet determined salary increases for faculty and most staff. For the small share of UC employees who are represented, most units already have negotiated 3 percent salary increases in 2020‑21. Four remaining units have open contracts. Every 1 percent increase in salaries—across all represented and nonrepresented employees at both segments—would cost about $90 million ($45 million at each segment).

Pensions

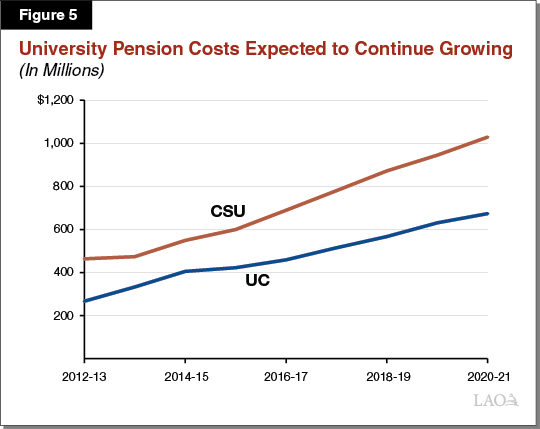

Both Segments Have Unfunded Pension Liabilities. Similar to most government agencies, UC and CalPERS (on behalf of CSU) fund pension benefits by setting aside and investing contributions made by the employer and employee during an employee’s career. In past years, these systems did not fully fund pension benefits earned by employees. While this underfunding does not affect the pensions of existing retirees, the state and universities currently lack adequate funds to fully pay for pension benefits that today’s employees will be owed when they retire. Currently, 80 percent of UC pension liabilities and 70 percent of CalPERS pension liabilities (including CSU employees) are funded. In dollar terms, UC’s unfunded pension liability is $16.6 billion (of which around 30 percent is associated with core funding) and the state’s unfunded CalPERS liability is $59.7 billion (with no CSU‑specific breakout available).

State and Segments Have Long‑Term Plans to Address Unfunded Liabilities. The UC Board of Regents and the CalPERS board have both developed plans to pay down their respective pension system’s unfunded liabilities gradually over time. The plans entail increasing contribution rates each year. Whereas CalPERS’ long‑term funding plan remains on track, UC’s plan has fallen short. To address the shortfall, UC has borrowed money (mostly from internal sources), which it is paying back from its operating budget. To help accelerate the pay down of unfunded liabilities, the Legislature in recent years has provided supplemental funding both for CalPERS and UC’s retirement program.

Pension Costs Set to Increase in 2020‑21. As Figure 5 shows, UC and CSU employer pension costs have grown notably over the last several years—more than doubling since 2012‑13. The higher pension costs are the result of (1) salary growth over the period, (2) the plans developed by UC and CalPERS to address unfunded pension liabilities, and (3) changes in the assumptions used to calculate liabilities. (Notably, both UC and CalPERS have adopted more conservative investment earnings expectations, which have led to larger contributions now and improved the likelihood the funding plans remain on track.) Based on planned employer contribution rate increases in 2020‑21, we estimate university pension costs to increase about $105 million ($60 million at CSU and $45 million at UC).

Health Benefits

Universities Subsidize a Portion of Health Costs for Employees and Retirees. At both universities, employees receive a subsidy to cover a portion of health premium costs, with remaining costs paid out of pocket by the employee or retiree. The subsidy is generally calculated by averaging the cost of the most popular plans among employees. At UC, lower‑income employees receive a larger subsidy than higher‑income employees. For example, UC covers 94 percent of the average cost for employees earning $56,000 or less per year compared to 75 percent for employees earning more than $167,000. For CSU, which participates in CalPERS’ health benefit program, employees generally receive the same subsidy regardless of salary. Known as the “100/90” formula, CSU generally pays 100 percent of the average premium cost for active and retired employees and 90 percent of the average additional premium costs for dependents.

Due to Pay‑As‑You‑Go Funding Approach, Both Segments Have Large Unfunded Retiree Health Liabilities. In contrast to pension benefits, the state and the universities do not set aside and invest funds during an employee’s career for retiree health benefits. Instead, the costs of these benefits are funded on a “pay‑as‑you‑go” basis after the employee retires. Because of this pay‑as‑you‑go approach, virtually all of the universities’ retiree health liabilities are unfunded. As of July 2018, CSU’s unfunded retiree health liability is estimated to be $13.1 billion. UC’s unfunded liability is $18.9 billion, of which around 30 percent is attributable to core‑funded retirees.

Health Spending Expected to Increase in 2020‑21. In 2019‑20, the state is spending around $900 million on CSU employee and retiree health care costs. UC is spending around $680 million on health benefit costs for core‑funded employees and retirees. Based on projected premium cost increases, as well as increases in the number of CSU and UC retirees, we estimate health benefit costs in 2020‑21 will increase around 6 percent at each segment, resulting in a combined cost increase of around $90 million ($55 million at CSU and $35 million at UC).

Facilities and Infrastructure

In this section, we describe two key facility‑related cost pressures: (1) maintenance and (2) debt service on approved construction and renovation projects.

Maintenance

Both Segments Have Sizable Maintenance Backlogs. Like most state agencies, UC and CSU are expected to dedicate a portion of their core budgets for facility maintenance, such as keeping electrical and plumbing systems in working order. Due to many years of underfunding maintenance, however, the systems have accrued billions of dollars in maintenance backlogs. According to university leadership, the systems have underfunded maintenance to manage past budget reductions and ensure operating funds are available for other budget purposes. CSU estimates its backlog for maintenance on its academic facilities and related infrastructure totals $4.5 billion across its 23 campuses. UC currently estimates its backlog at $6.2 billion across all ten campuses, but staff at the Office of the President believe the estimate is incomplete. UC is currently in the process of developing a more consistent systemwide estimate, which the Office of the President expects to release by November 2020.

Segments Are Developing Long‑Term Plans to Address Backlogs. Since 2015‑16, the state has provided a total of $573 million in one‑time funding to help address the systems’ maintenance backlogs. Despite these recent appropriations, neither the state nor the universities have long‑term plans to address these backlogs. To better guide state funding decisions, the Legislature directed the universities as part of the 2019‑20 budget to develop such plans. CSU is expected to submit its plan to the Legislature by January 2020. UC has until January 2021, shortly after it completes its systemwide facility condition assessment, to submit its plan.

Deferred Maintenance Is Another Significant Cost Pressure. Without a long‑term plan in place to address maintenance issues, the state does not yet have explicit expectations as to how much the systems should spend in 2020‑21 and beyond. Though plans are not yet in place, addressing maintenance backlogs will continue to be a significant cost pressure. For example, CSU estimates it would have to spend about $360 million more in 2020‑21 just to keep its backlog from growing. While comparable estimates do not exist for UC, the magnitude of these costs likely are similar to CSU.

Debt Service Costs

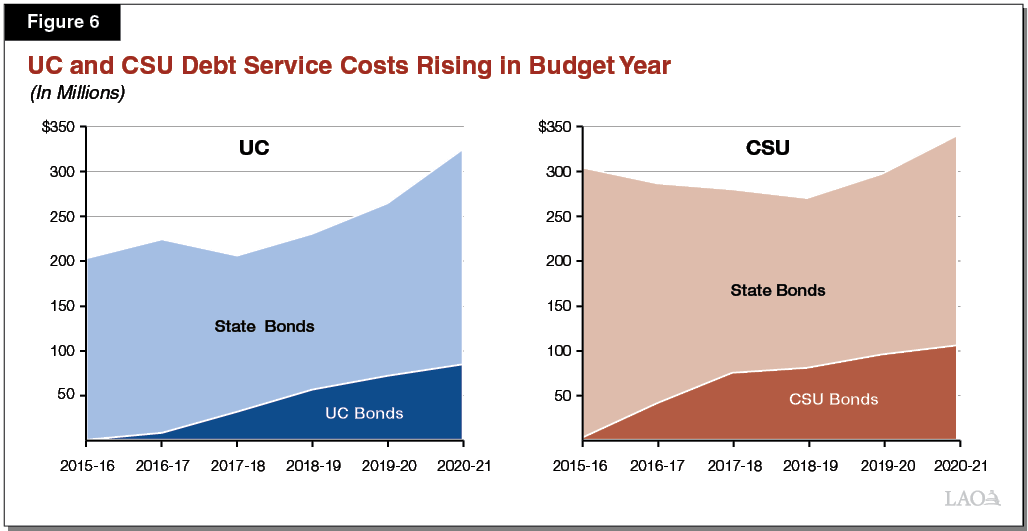

Since 2013‑14, Universities Pay Debt Service Out of Operating Budgets. Prior to 2013‑14, the state sold bonds to pay for larger facility renovation and construction projects on behalf of the universities. The state then made the associated annual debt payments (from the General Fund). The state changed this approach for UC in 2013‑14, and took a similar action for CSU the following year. Under the new approach, the universities issue their own bonds for facility projects and pay back the debt from their operating budgets. In a related action, the state shifted a General Fund amount to the universities’ operating budgets to reflect the debt service the state had previously paid directly (around $300 million at CSU and $400 million at UC). Moving forward, the universities are expected to pay off all debt—for both previous state bonds and new university bonds—from their operating budgets. The universities must receive approval from the state to fund new projects under this new process.

Debt Service Costs on Existing Projects Set to Increase in 2020‑21. As Figure 6 shows, debt service on previously approved state and university bonds is expected to rise in 2020‑21 by about $100 million ($60 million at UC and $40 million at CSU). The rising costs are the result of decisions by the state and universities on what projects to approve, when to issue bonds, and how to structure debt payments. The systems have prepared for these rising costs somewhat differently. CSU staff indicate that university leadership anticipated these cost increases in previous years and set aside funding in reserves to cover them. UC staff, by contrast, indicate that the university did not set aside funds for the cost increase. UC staff suggest the university will cover costs through one‑time internal borrowing.

Segments Proposing a Total of 29 Projects for 2020‑21. UC is proposing a total of $551 million in bond authority for six new projects. Most of these projects would address seismic deficiencies and deferred maintenance throughout the system. Also included in UC’s package of proposals is $100 million to construct a new building at UC Riverside’s school of medicine. CSU is proposing a total of $2.6 billion in bond authority for 23 new projects. Like UC, many CSU projects would address seismic deficiencies and deferred maintenance throughout the system. CSU’s package of proposals also includes several new instructional buildings. Though better estimates likely will be available in the coming months, our preliminary estimate is that annual debt service to finance all 29 projects across the two systems would be about $210 million ($40 million for UC projects and $170 million for CSU projects).

Seismic Renovation Projects Likely Are Significant Long‑Term Cost Pressure. Seismic renovation projects focus on upgrading building support structures and mitigating life‑safety risks from earthquakes. When discussing cost pressures with our office, staff at both university systems stated that campuses have substantial backlogs of seismic renovation projects. To date, though, neither segment has completed comprehensive assessments of its buildings’ seismic risks nor estimated the cost to correct deficiencies. As part of the 2019‑20 budget, the Legislature directed the segments to undertake these assessments and develop plans to address their seismic renovation backlogs. Based upon the limited information currently available, seismic‑related costs likely are significant. For example, UC officials recently reported that an initial systemwide review identified around 70 large, high‑use classroom buildings that pose life‑safety risks. The total cost of renovating these 70 facilities likely would range from the high hundreds of millions of dollars to low billions of dollars. According to UC, the associated increase in annual debt service costs likely would range from the mid‑to‑high tens of millions of dollars.

Enrollment

In this section, we discuss cost pressures relating to undergraduate and graduate enrollment.

Enrollment Growth Can Increase Costs in Three Ways. Enrollment growth is another significant cost pressure for the universities. UC and CSU typically respond to enrollment growth by hiring more faculty, teaching assistants, academic advisors, and other support staff. Historically the state has funded these costs by providing the systems with a General Fund subsidy for each additional student. Enrollment growth also increases costs because a sizable portion of new UC and CSU students qualify for Cal Grants. Adding more students and faculty also can increase pressure on the state and systems to construct new classrooms, teaching laboratories, faculty offices, and other academic spaces. These construction projects increase debt service costs, and the new facilities ultimately increase the amount of funding needed for operations and maintenance.

Certain Factors Influence Undergraduate Enrollment Decisions. Historically, the state’s freshman eligibility policies have influenced the Legislature’s decisions about undergraduate enrollment levels. Under these policies, the top one‑eighth (12.5 percent) of high school graduates in California are eligible to attend UC and the top one‑third (33 percent) are eligible to attend CSU. (Those not eligible as freshmen can enroll in community colleges and then transfer to the universities as upper‑division students.) To ensure access under these policies, the state has sought to fund enrollment growth in years when the number of high school graduates increased. The Legislature also has expected the universities to adjust their freshman admission requirements such that they continue drawing from their designated eligibility pools.

State Has No Explicit Policy on Graduate Enrollment. In contrast to undergraduate enrollment, the state does not have a longstanding policy that guarantees California students access to graduate education. In past years, the state has not specified how enrollment growth was to be divided between undergraduate and graduate enrollment, effectively giving the systems flexibility to make this decision. The systems typically considered the state’s workforce needs (such as for teachers, engineers, physicians, and lawyers) when planning for graduate enrollment. In addition, the systems have tended to grow graduate enrollment along with undergraduate enrollment. This is because campuses rely on graduate students to serve as teaching assistants in undergraduate courses and research assistants to new faculty. In recent years, the state has reversed course by specifying whether funds are to be used for undergraduate or graduate enrollment. In most of these years, funds were restricted for undergraduate enrollment growth.

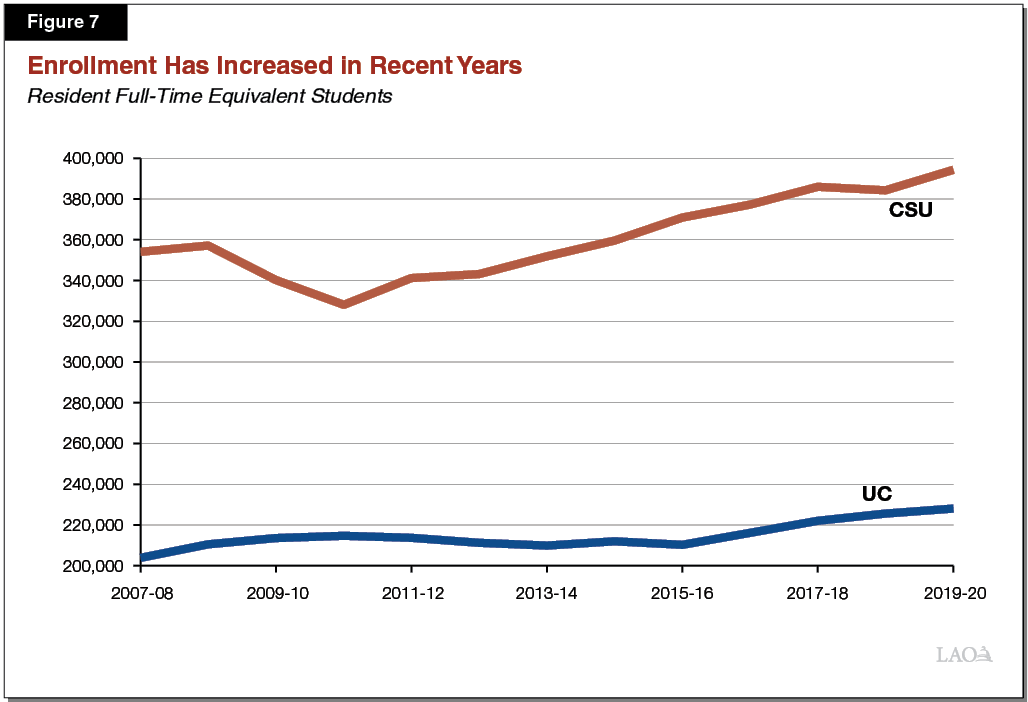

UC and CSU Enrollment Trends Vary Somewhat. In 2019‑20, CSU is expected to enroll 394,000 resident students, and UC is expecting to enroll 228,000 resident students (Figure 7). These levels reflect all‑time highs for the universities. Enrollment at CSU has grown steadily since 2010‑11, with average annual growth of 2.1 percent. By comparison, UC enrollment was virtually flat from 2008‑09 through 2015‑16, followed by notable increases the past few years. The enrollment trends at CSU and UC generally reflect the Legislature’s enrollment growth decisions.

Legislature Faces Certain Enrollment Decisions in Upcoming Budget Cycle. The Legislature faces a decision about how many CSU students to fund in 2020‑21. For UC, the Legislature faces a decision about how many students to fund in 2021‑22. The state tends to set UC’s enrollment targets one year in advance, as this allows the Legislature to better influence UC fall admission decisions, which usually occur in the spring before the state budget is enacted. (UC will have made its 2021‑22 admissions decisions by spring 2021, before the 2021‑22 budget has been adopted.) We estimate growing enrollment by an additional 1 percent would cost the state around $40 million at UC and $45 million at CSU. (These estimates include the cost to hire additional faculty and staff and cover the cost of tuition for students eligible to receive Cal Grants.) To assist the Legislature in making its enrollment growth decisions, we discuss four key enrollment drivers below.

High School Graduates Are Projected to Dip, Then Rise Slightly. Consistent with historical practice, the Legislature may wish to consider adjusting UC and CSU enrollment to keep pace with changes in California’s high school graduates. The Department of Finance projects that the number of public high school graduates in 2019‑20 (affecting the incoming fall 2020 freshman class) will decrease by 0.4 percent, followed by a 1 percent increase in 2020‑21 (affecting the incoming fall 2021 freshman class).

Both Systems Are Drawing From Beyond Their Freshman Eligibility Pools. According to a study of the high school class of 2015, UC was found to be drawing from 14 percent of high school graduates, somewhat higher than the state’s historical eligibility expectation of 12.5 percent. The same report found that CSU was drawing from 41 percent of high school graduates—notably higher than the state’s historical eligibility expectation of 33 percent. Updated information since the release of this study suggests that the universities likely are drawing from even larger pools today. Neither UC nor CSU, however, has correspondingly adjusted its freshman admission criteria. To the extent that the Legislature wishes the universities to draw from their historical pools of high school graduates, additional enrollment growth funding is not warranted.

Many Eligible Undergraduate Students Are Referred to Less Selective Campuses. While eligible students are guaranteed admission to UC and CSU, they are not guaranteed admission to a specific campus. Both systems refer eligible students who are not admitted to their campus of choice to a lower‑demand campus with remaining space. Historically, relatively few applicants choose to enroll at a campus to which they have been redirected. Supporting more enrollment growth could enable both systems to accommodate more applicants at their campus of choice. The Legislature could weigh this benefit against the other cost pressures described in this report.

More Undergraduate Enrollment Could Increase Pressure for More Graduate Enrollment. Were the Legislature interested in funding more undergraduate students, the universities would likely experience pressure to fund more graduate student assistants to support the additional undergraduate courses and faculty. Currently, UC enrolls around six undergraduate students for every graduate student. At CSU, the ratio is around ten undergraduate students to every graduate student.

Other Cost Pressures

In this section, we analyze other major pressures to expand the level and scope of university services.

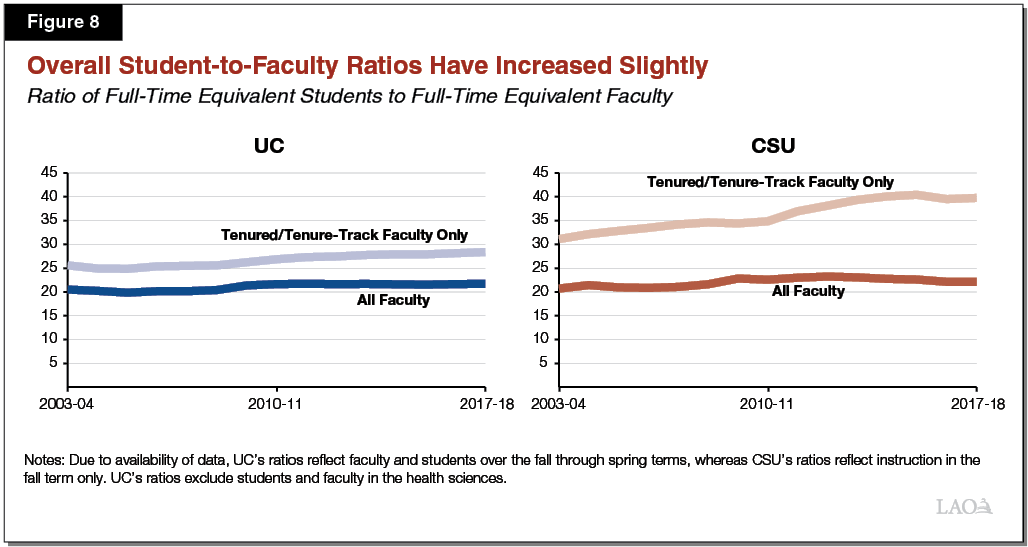

Recently, Pressure Has Mounted to Hire More Faculty. As Figure 8 shows, UC’s and CSU’s overall student‑to‑faculty ratio has increased slightly since 2003‑04—both rising from 21 to 22. At CSU, the mix of faculty has also changed over the years, with the system relying less on tenured/tenure‑track faculty and more on lecturers to deliver instruction. In 2003‑04, CSU had 31 students for every tenured/tenure‑track faculty. By 2017‑18, the number of students per tenured/tenure‑track faculty had risen to 40. The increase in the ratio of tenured/tenure‑track faculty at UC has been much more gradual than at CSU. In response to the trend at CSU, the 2018‑19 and 2019‑20 budget packages directed CSU to prioritize hiring more tenure‑track faculty with its state funding augmentations. Though the UC Office of the President has regularly requested funds to hire more faculty and reduce its student‑to‑faculty ratio, the state has not directed UC to prioritize state funding augmentations for this purpose.

State Continues to Focus on CSU’s Graduation Initiative. In an effort to boost historically low graduation rates at CSU campuses, the state over the past several years has provided ongoing and one‑time augmentations for the system’s Graduation Initiative. This initiative aims to increase four‑ and six‑year graduation rates for freshmen to 40 percent and 70 percent, respectively, by 2025. (For comparison, CSU’s four‑year rate historically has been below 15 percent and its six‑year rate below 50 percent.) While campuses have flexibility on how to spend their funds, most use their funds to hire additional faculty, offer more course sections in high‑demand areas, and provide more student support services. Currently, CSU is spending $243 million annually in ongoing funding on the initiative. As boosting CSU student outcomes likely remains a statewide priority, the Legislature may face pressure to identify funding to further expand the initiative in 2020‑21.

Legislature Likely to Remain Interested in Reducing Nonresident Enrollment at UC. In response to concerns that nonresident students are displacing resident student at selective campuses, the Legislature the past few years has sought to limit nonresident enrollment at UC. Specifically, in 2017‑18, the Legislature directed the Board of Regents to develop a policy limiting nonresident enrollment at each campus, and, in 2018‑19, the Legislature directed UC to estimate the cost to reduce nonresident enrollment. UC submitted its plan in April 2019, which would start in 2020‑21 and eventually reduce nonresident enrollment to 10 percent of entering freshmen by 2029‑30 at each campus. UC estimates the annual cost to attain this reduction—resulting from replacing the foregone nonresident supplement tuition revenue and enrolling more resident students—would increase from an initial $8 million in 2020‑21 to $455 million by 2029‑30. The state did not formally commit to funding this plan in the 2019‑20 budget.

State Recently Has Signaled Interest in Supporting Student Hunger, Homelessness, and Mental Health Initiatives. In recent years, the universities and the state have sought to address a number of nonacademic issues facing students. According to survey data, more than 40 percent of undergraduate students at CSU and UC have experienced food insecurity (defined as having low food intake and/or lack of variability in diet). A smaller share of students—about 10 percent at CSU and 5 percent at UC—have experienced homelessness. Campuses have also experienced a notable rise in demand for on‑campus student mental health services. For example, UC reports a 78 percent increase in students visiting a campus counseling center between 2007‑08 and 2017‑18. During the same period, overall enrollment increased by 27 percent. In 2019‑20, the Legislature provided a total of $30 million in ongoing funding and $18 million in one‑time funding for hunger, homelessness, and mental health initiatives at UC and CSU. Given the reported scale of these issues among students, the Legislature could face pressure to provide additional funding to expand services in 2020‑21.

State Exploring Possible New Campuses and Medical Schools. At CSU, the 2019‑20 budget provided $4 million one‑time General Fund for the Chancellor’s Office to study whether to develop new campuses in several specified areas of the state. Provisional language requires CSU to submit the results of the study to the Legislature by July 2020. At UC, the 2019‑20 budget authorized a new medical school project at or near the Merced campus, presumably with the intention of opening a medical school at that campus. The budget did not set a deadline for UC to submit a specific project proposal to the Legislature. Because new campuses or medical schools will require future authorization and implementation, the Legislature does not face immediate costs in 2020‑21. Nonetheless, the Legislature may wish to keep these projects in mind as it sets its ongoing budget priorities in 2020‑21. Were new campuses or medical schools to be approved over the next few years, the resulting cost increases would be substantial, with significant long‑term fiscal implications.

Key Planning Issues

In this section, we examine the extent to which the state General Fund budget has capacity to cover UC and CSU cost pressures in the budget year. We end the section by identifying three options within the universities’ budgets to expand this capacity.

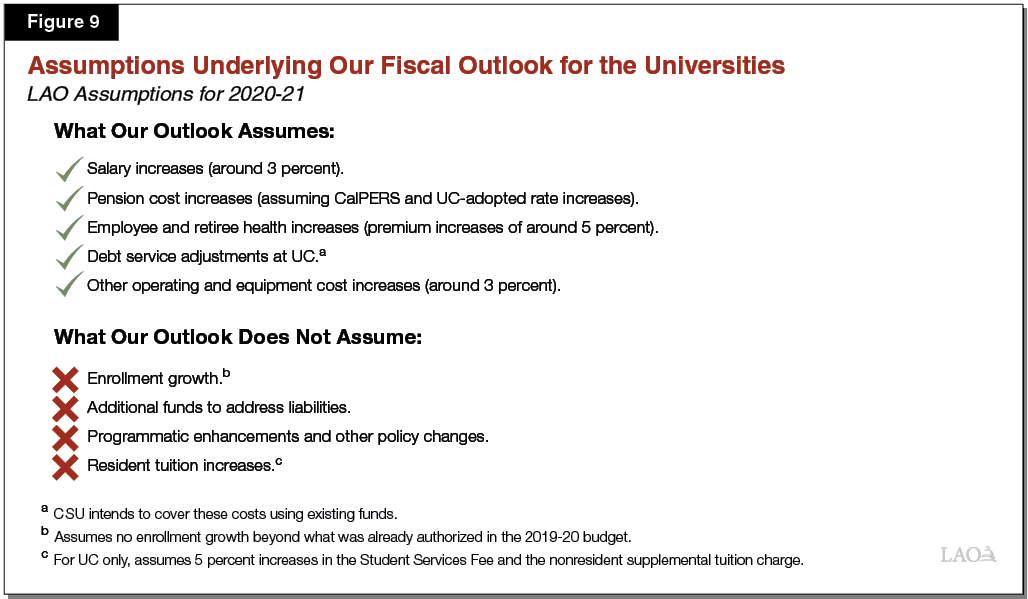

Implications of State Fiscal Outlook for Universities

In 2020‑21, State Might Have a Sizable Budget Surplus . . . In our recent report, The 2020‑21 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook, we assess the state’s General Fund condition for the upcoming 2020‑21 fiscal year. If economic growth were to continue at our assumed levels, we estimate the state in 2020‑21 would have enough funds to cover cost increases for its current level of services. For the universities specifically, we assume the state covers inflationary increases in salaries, pensions, health care, facility debt service costs, and other operating expenses (Figure 9). After covering these increases and increases to other state programs, we estimate the state would have a $7 billion surplus. The surplus would be available for addressing legislative priorities across all areas of the budget. (As discussed in the nearby box, we made certain inflationary assumptions in projecting university costs. A different set of assumptions would affect the size of the state’s estimated operating surplus.)

University Forecast Depends Upon Certain Assumptions

In developing our fiscal outlook each year, our office must decide how to project future cost increases in existing operations. This year for the University of California and the California State University, we projected growth in salaries and “other operating expenses” (such as supplies, utilities, and contracts) using a composite inflationary index reflecting changes in consumer prices and state economic output. Using this composite index, we assumed salary and other operating expenses grow by 2.8 percent in 2020‑21. For employee benefit cost increases, we projected growth based upon recent state actuarial assumptions regarding pension contribution rates and health premium increases.

Using different assumptions than we made would result in a different estimate of the state’s operating surplus. For example, the state and universities could fund salary increases higher or lower than 2.8 percent in 2020‑21. The universities’ actual employee benefit costs in 2020‑21 also could be higher or lower than we assume. Furthermore, the Legislature could decide not to adjust other operating expenses for inflation. Historically, the state has not provided direct adjustments for these operating costs, though it sometimes has provided indirect increases by applying a percent increase to the universities’ total budgets.

. . . But Limited Capacity for New Ongoing Spending Commitments. While $7 billion reflects a sizable projected surplus, we have identified numerous risks to the state’s budget condition. For example, our growth scenario assumes the federal government approves a state policy intended to draw more federal funding for state health programs. Were the state not to receive federal approval, General Fund costs would rise notably. Furthermore, state revenues would fall were the state to experience an economic recession. Given these risks, we strongly encourage caution when making decisions about new ongoing spending. As a rule of thumb, we recommend the Legislature limit new ongoing spending commitments across all areas of the state budget to around $1 billion. The Legislature likely would want to consider UC and CSU enrollment growth, expansion of services, and new programs within the context of all the other possible calls on this $1 billion. A particularly challenging part of the upcoming budget season could be deciding how to prioritize these additional university cost pressures among all the state’s other ongoing spending priorities.

Recommend Legislature Focus on Addressing Unfunded Liabilities. After making ongoing spending decisions, the remaining surplus would be available for larger state reserves, accelerated debt payments, and other one‑time commitments. After making its decisions about reserves, if the Legislature wishes to direct some of the state’s remaining surplus to the universities, we recommend it give high priority to addressing existing unfunded liabilities, including the universities’ unfunded pension and retiree health care liabilities, facility maintenance backlogs, and seismic renovation backlogs. The Legislature could designate one‑time funds for these purposes, though ultimately the Legislature likely would need to provide funding over many years, and in some cases increase ongoing support, to eliminate the liabilities and backlogs. Addressing existing liabilities is essential to ensuring the state’s and universities’ long‑term fiscal health. As with virtually all unfunded liabilities, addressing them is costly and difficult in the short run, especially as the state faces many other competing cost pressures. In the long run, however, not addressing liabilities results in even higher costs—pushing even more difficult situations onto future generations.

Other Options for Addressing Cost Pressures

Three Other Options for Addressing Cost Pressures. The Legislature has options within the universities’ budgets that would allow it to expand budget capacity and address additional cost pressures or reduce the amount of state funding required to address identified priorities. Below, we discuss three such options—raising tuition levels, pursuing efficiencies in university operations, and using university reserves to meet strategic goals.

Raising Tuition Levels Would Help Address Additional Cost Pressures. Recognizing the private benefit from earning a college degree, the state implicitly shares college costs with students through their tuition charge. The state does not have a formal policy, though, for what share of cost nonfinancially needy students should be expected to bear. Since emerging from the last recession, the state generally has kept tuition flat and elected to cover virtually all approved ongoing cost increases from the state General Fund. For the purposes of our fiscal outlook, we assume the state continues this practice. That is, we assume UC and CSU do not adopt increases to resident tuition levels. (We did assume UC adopts a 5 percent increase in the Student Services Fee and the nonresident supplemental tuition charge, also consistent with past actions.) While the state budget appears to have the capacity to support some university cost increases without a tuition increase, raising tuition would allow for other university cost pressures to be addressed. We estimate that every 1 percent increase in tuition generates associated revenue of about $15 million at UC and $10 million at CSU. (These estimates reflect the amount of funding available after providing Cal Grants and university‑administered financial aid to financially needy students.)

Additional Efficiencies Would Help Address Cost Pressures. In recent years, the state has sought to find efficiencies in the university systems that would help offset cost increases. For example, the universities have been pursuing changes in their procurement practices that have reduced some of their ongoing operating costs, freeing up funding for other ongoing purposes. The state also could avoid certain long‑term capital costs by directing the universities to use their existing facilities more intensively, offer more online instruction, and expand the use of summer term. The magnitude and timing of savings resulting from these efficiencies would depend upon which of these options were pursued.

Use of Campus Reserves Could Be Part of Strategic Plan for Covering Costs. Another approach to expanding budget capacity is to factor UC and CSU campus reserves into budget decisions. While campuses already have committed a sizable portion of their reserves for certain future costs, potentially hundreds of millions of dollars remain available. In preparation for a future economic recession, the Legislature could allow campuses to maintain and expand these reserves in 2020‑21. Such an approach would add to the state’s total level of reserves and strengthen the state’s and campuses’ ability to withstand a future downturn. Alternatively, the Legislature could direct campuses to use some of their reserves in the budget year to address specified cost pressures (such as deferred maintenance) on a one‑time basis.

Conclusion

This report has sought to identify university cost pressures facing the Legislature in the budget year. The report also has suggested a framework for addressing some of these cost pressures in light of the state’s overall fiscal outlook and discussed risks to the General Fund. Moreover, the report has identified a few options for expanding budget capacity, including by raising tuition and pursuing operational efficiencies. Over the coming months, the Legislature will be weighing in on all these matters. Upon release of the Governor’s budget in early January, we will turn to analyzing the Governor’s specific budget proposals for UC and CSU. Until that time, the Legislature can be proactive in considering its highest budget priorities for UC and CSU.