LAO Contact

January 9, 2020

Assessing Vulnerability of State Assets to Climate Change

In this post, we discuss current efforts being made by state departments to assess the potential for severe risks to state facilities posed by climate change, such as sea level rise and more wildfires. In summary, we find that most state agencies are only at the early stages of conducting such assessments, which are a critical first step of a multistep process of planning for climate change and implementing projects and policies to reduce the risks to public safety and welfare. Consequently, much more work will need to be done before state agencies, their facilities, and the people they serve are adequately protected. We provide a number of oversight questions the Legislature can use to monitor what progress is being made by individual state agencies, as well as inform future legislative guidance to state agencies and spending decisions.

Climate Change’s Potential to Severely Damage State Assets and Programs

Future Climate Impacts Could Cause Damages, Increase Costs, and Disrupt Services. Research—including evidence summarized in California’s Fourth Climate Change Assessment—projects that climate change could have a myriad of consequential effects throughout California. These include sea-level rise, inland flooding, more severe heat days, more frequent drought, and increased risk of wildfires. These climate change effects have the potential to damage state and local infrastructure, disrupt the provision of key services, impair natural habitats, and affect regional economies. For example, catastrophic wildfires that have occurred in California in recent years have caused many deaths and injuries, billions of dollars in damages to public infrastructure and other costs, and tens of billions of dollars in private sector losses. In addition, seas along the California coast are projected to rise between 2 and 7 feet by 2100. One study estimates that by 2100 sea-level rise, combined with the impact of a 100-year storm, could put $150 billion of property value at risk in California, as well as cause loss of beaches and other coastal habitats. (For more on sea-level rise, see our report Preparing for Rising Seas: How the State Can Help Support Coastal Adaptation Efforts.)

State Assets Worth Many Billions of Dollars Provide Key Services. As shown in Figure 1, the state owns and operates a wide range of physical assets and infrastructure, including the state highway system, university campuses, parks and historic structures, and prisons. These assets are worth many billions of dollars. Just as importantly, state agencies use these facilities and structures to provide a myriad of services to tens of millions of Californians and to support the state’s robust economy. (In addition, the state is currently undertaking other infrastructure projects, including the construction of several new state office buildings in Sacramento and a portion of the high-speed rail project in the Central Valley.)

Figure 1

Major State‑Owned Infrastructure

|

Transportation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Higher Education |

|

|

|

Water Resources |

|

|

|

|

|

Natural Resources |

|

|

|

|

Criminal Justice |

|

|

|

|

Health and Human Services |

|

|

|

|

Other Facilities |

|

|

Adaptation Is a Multistep Process

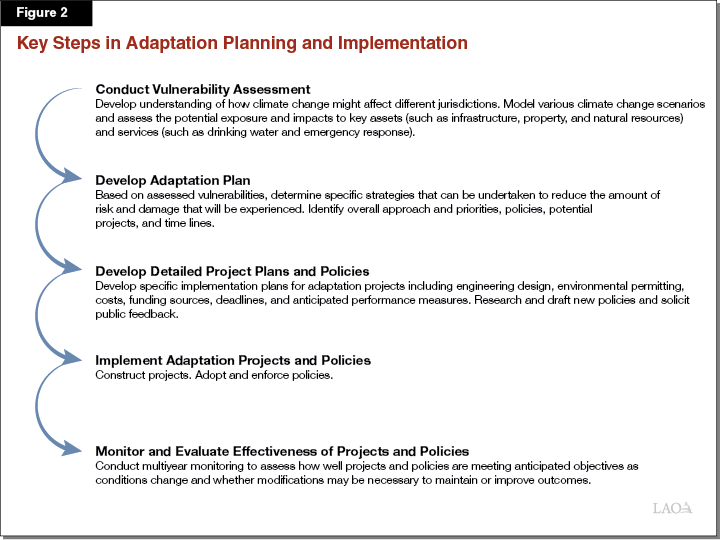

Planning for Effects of Climate Change Is Key to Building Resiliency. All sectors in California—including residents, businesses, agricultural producers, and state and local governments—have the potential to be adversely impacted by the effects of climate change. Planning for these impacts is key to longer-term resiliency by developing strategies to minimize the worst potential impacts. As shown in Figure 2, developing and implementing effective risk reduction measures is a multistep process that includes assessment of risks and costs, development of adaptation plans, selection of specific projects and policies, implementation, and ongoing monitoring. Because of the number of steps and their potential complexity, it often will take years to develop and implement mitigation measures. For this reason, developing an effective response requires early planning—before the worst climate change impacts are being felt.

Vulnerability Assessments Are Necessary First Steps in Planning. Before a public or private entity can determine what actions to take in response to climate change, it must first determine its susceptibility to climate change impacts—referred to as a vulnerability assessment. For example, a coastal city might assess the degree to which its roads and other infrastructure are at risk of flooding due to sea-level rise, a water agency might estimate how its water supplies would be affected under different drought scenarios, or a county might evaluate which of its communities are most likely to be threatened by increased risks of wildfires. When done well, these types of assessments are complex, usually requiring evaluation of risks under different climate change scenarios and over different time periods. They also involve estimating the likelihood and financial costs associated with projected impacts to specific assets and communities, while taking into account the inherent ability of those assets and communities to withstand some of the potential harms. Ultimately, vulnerability assessments are a critical first step to take in the longer-term adaptation planning not only because they provide an identification of potential risks, but they also serve as a baseline against which to compare alternative mitigation options.

Some Departments Have Taken Initial Steps Towards Vulnerability Assessments

California agencies have completed several reports in recent years designed to identify climate change risks and provide guidance to state and local governments on how to do adaptation planning. We list several of the key reports in Figure 3. Notably, these documents generally focus broadly on statewide climate change risks and planning strategies, rather than being vulnerability assessments for specific departments or facilities. We describe steps taken by individual state departments below.

Figure 3

California Climate Change Assessments and Guidance Documents

|

Document |

Summary |

Departments |

Year |

|

California Adaptation Planning Guide: Planning for Adaptive Communities |

Guidance for local governments and regional collaboratives to address the consequences of climate change. |

CalEMA, CNRA |

2012 |

|

Safeguarding California Plan: 2018 Update |

Catalogue of ongoing actions and recommendations to protect infrastructure, communities, services, and the natural environment from climate change. |

CNRA |

2018 |

|

Planning and Investing for a Resilient California: A Guidebook for State Agencies |

Guidance document on steps of climate change planning for state agencies. |

OPR |

2018 |

|

California’s Fourth Climate Change Assessmenta |

Scientific assessments of climate‑related vulnerabilities. |

OPR, CEC, CNRA |

2018 |

|

Paying it Forward: The Path Toward Climate‑Safe Infrastructure in California |

How to incorporate climate change projections into the state’s infrastructure design, planning, and implementation. |

CNRA |

2018 |

|

aPrevious climate change assessments were released in 2006, 2009, and 2012. CalEMA = California Emergency Management Agency; CNRA = California Natural Resources Agency; OPR = Office of Planning and Research; and CEC = California Energy Commission. |

|||

Several Departments Have Done Preliminary Assessments in “Sustainability Roadmaps.” The most common adaptation planning effort undertaken by state agencies is the completion of Sustainability Roadmaps by 20 departments in 2018, as directed by Governor Brown and his administration. While not exclusively focused on vulnerability assessments, each Roadmap includes a chapter identifying potential risks from climate change. Specifically, they identify the top five facilities at risk for each of the following future climate impacts: sea-level rise, rising temperatures, and changes to precipitation.

While these evaluations use recent climate science projections to identify potential vulnerabilities to state assets and operations, they come with three limitations, making them more preliminary than fully developed vulnerability assessments. First, the roadmaps do not consistently include assessments of some potentially significant climate impacts, such as wildfires and longer or more frequent droughts. Second, focusing on only the top five facilities likely excludes some key department assets. For example, the California Department of Parks and Recreation identified the top five state parks and beaches most at risk from sea-level rise. Yet, roughly one-third of California’s coastline is under the jurisdiction of the department and likely to be impacted by sea-level rise in the future, meaning many other facilities and lands not identified in its roadmap are also at risk. Third, even where the roadmaps identify that a facility could be at risk under current climate projections, they generally do not provide a detailed evaluation of the degree of risk to those specific facilities or potential future costs that would occur if the facilities were damaged or services disrupted.

A Few Agencies Have Not Yet Undertaken Assessments. Several agencies with substantial infrastructure under their control—specifically, the University of California, California State University, judicial branch, and CalFire—have not completed system-wide assessments of their vulnerability to climate change. We note, however, a couple of individual university campuses, such as UC Berkeley, have undertaken assessments.

Caltrans and DWR Have Conducted More Robust Vulnerability Assessments. In addition to their roadmaps, two state departments have completed more fully developed vulnerability assessments. The California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) is in the process of completing vulnerability assessments for each of its 12 districts and has completed ten assessments to date. As part of this process, Caltrans has published summary reports, as well as more in-depth technical analyses. According to Caltrans, it will follow these up with reports that go into more depth and can be used to identify the projected costs to different facilities. These estimates could then be incorporated into future project prioritization decisions.

In addition, the Department of Water Resources (DWR) has completed a more in-depth vulnerability assessment of how climate change will impact its operations, and—in conjunction with the Central Valley Flood Protection Board—has assessed how climate change will impact the state’s management of flood control infrastructure as part of its 2017 flood protection plan update. It appears that a key reason why Caltrans and DWR have done more in-depth vulnerability assessments than other departments is that such analysis is consistent with their core missions around long-term infrastructure planning. (We also note that the Department of Fish and Wildlife has completed several vulnerability assessments of how climate change will affect various native plant and animal species in California, though these assessments are not specifically focused on state facilities or managed lands.)

Assessments Completed to Date Highlight Some Potential Risks

All of the assessments completed by state departments, even when preliminary, identify risks to state assets and operations. Sea-level rise, for example, is projected to impact not only state beaches and parks along the coast, but also could severely damage coastal transportation infrastructure, such as highways and railways in low-lying areas or along coastal bluffs. In addition, Caltrans finds that increased temperatures will affect infrastructure, potentially requiring changes to the types of pavements used in some areas, as well as shortening the lifespan of some pavement already installed. Some state agencies also project that an increase in the number of extreme heat days could reduce the number of summer days that certain employees can work, such as those who repair and maintain highways and levees. In addition, increased precipitation is cited in several roadmaps as increasing the likelihood of causing water damage and flooding to state facilities.

Ongoing Legislative Oversight Could Ensure Enhanced Focus by State Agencies

More Study Needed to Assess Risks, Define Priorities, and Consider Alternatives. Given the potential risks of climate change and the limited number of in-depth analyses completed to date, individual state agencies will need to do more work in coming years in order to advance the state’s climate adaptation efforts. Completing vulnerability assessments is only the first step. However, as described above, it is a necessary step in an effective adaptation planning process. Without these assessments, the state cannot make informed decisions about which specific risks to prioritize or what alternatives to adopt.

Legislative Hearings Can Be a Forum for Assessing Progress and Providing Direction. Over the coming years and decades, we should expect to see state facilities and programs experiencing the impacts of climate change more frequently. Moreover, the scale of these impacts will be magnified to the extent that the state (as well as local, federal, and private sector entities) has not implemented effective adaptation measures. In order to ensure that the administration continues and expands on its recent climate change adaptation planning efforts, we recommend that the Legislature conduct ongoing oversight of individual state departments. This could be done through a number of oversight activities, including budget and policy committee hearings. We recommend that the following questions be incorporated in future oversight efforts of individual state agencies:

Progress Completing Vulnerability Assessments. What assessments have been completed, and what additional assessments are underway or planned? How comprehensive and detailed are these assessments? What is the time line for completing future assessments? Do departments have the requisite expertise and resources to complete these assessments?

Identification of Key Risks to Facilities and Services. Which state assets are projected to be impacted by climate change, and how severe are those risks to the facilities, the people they serve, and the welfare of state employees? Over what time frames are these risks to facilities and services anticipated to occur under different climate change models?

Financial Costs to the State. What are the projected costs of doing nothing? What are the estimated costs of the projected climate impacts, including to repair or replace facilities at high risk of damage from climate change impacts? To what extent could there be broader financial or economic impacts from major climate-caused disasters, such as impacts on regional economies and tax revenues?

Beyond Assessment—Development and Implementation of Adaptation Plans. Based on risks identified in vulnerability assessments, which departments should develop adaptation plans and how long will they take to complete? How should the state prioritize addressing the various risks to facilities and services within and across departments, as well as different regions of the state? As adaptation plans are completed, what alternatives are available to minimize the worst risks? How much will it cost to implement priority adaptation projects, and what fund sources are available? What challenges will departments face in implementing adaptation projects quickly and effectively? How will departments coordinate with local jurisdictions to ensure that projects meet both state and regional adaptation objectives and maximize cross-jurisdictional resiliency efforts? How will we know if adaptation efforts are working effectively?

Additional Considerations. Should a single state agency take the lead in coordinating all state agencies’ climate change adaptation efforts to ensure consistency and quality of plans, and if so, which agency is best positioned to do this? How should the state prioritize taking potentially costly actions to address risks to facilities relative to other infrastructure-related demands, such as to fulfill the needs of increasing populations, rehabilitate facilities to address seismic risks, and address deferred maintenance and aging facilities? How should the state prioritize adaptation funding and assistance for state facilities versus those owned by local governments or private entities? How should the state fund its long-term climate change adaptation efforts, such as from the state’s General Fund, bonds, or special funds?