LAO Contacts

- Frank Jimenez

- Caltrans

- SB 1 Revenues

- Eunice Roh

- California Highway Patrol

- Department of Motor Vehicles

- MVA Fund Condition

- Helen Kerstein

- High-Speed Rail Authority

February 10, 2020

The 2020-21 Budget

Transportation

- Cross Cutting Issues

- Caltrans

- Department of Motor Vehicles

- California Highway Patrol

- High‑Speed Rail Authority

- Summary of Recommendations

Executive Summary

Overview of Governor’s Transportation Budget

Total Proposed Spending of $26.9 Billion. The Governor’s budget provides a total of $26.9 billion from all fund sources for the state’s transportation departments and programs in 2020‑21. This is a net increase of $3.4 billion, or 14 percent, over estimated expenditures for the current year. Specifically, the budget includes $15.5 billion for the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), $3 billion for local streets and roads, $2.9 billion for the High‑Speed Rail Authority (HSRA), $2.7 billion for the California Highway Patrol (CHP), $1.4 billion for the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV), $1 billion for state transit assistance, and $400 million for various other transportation programs.

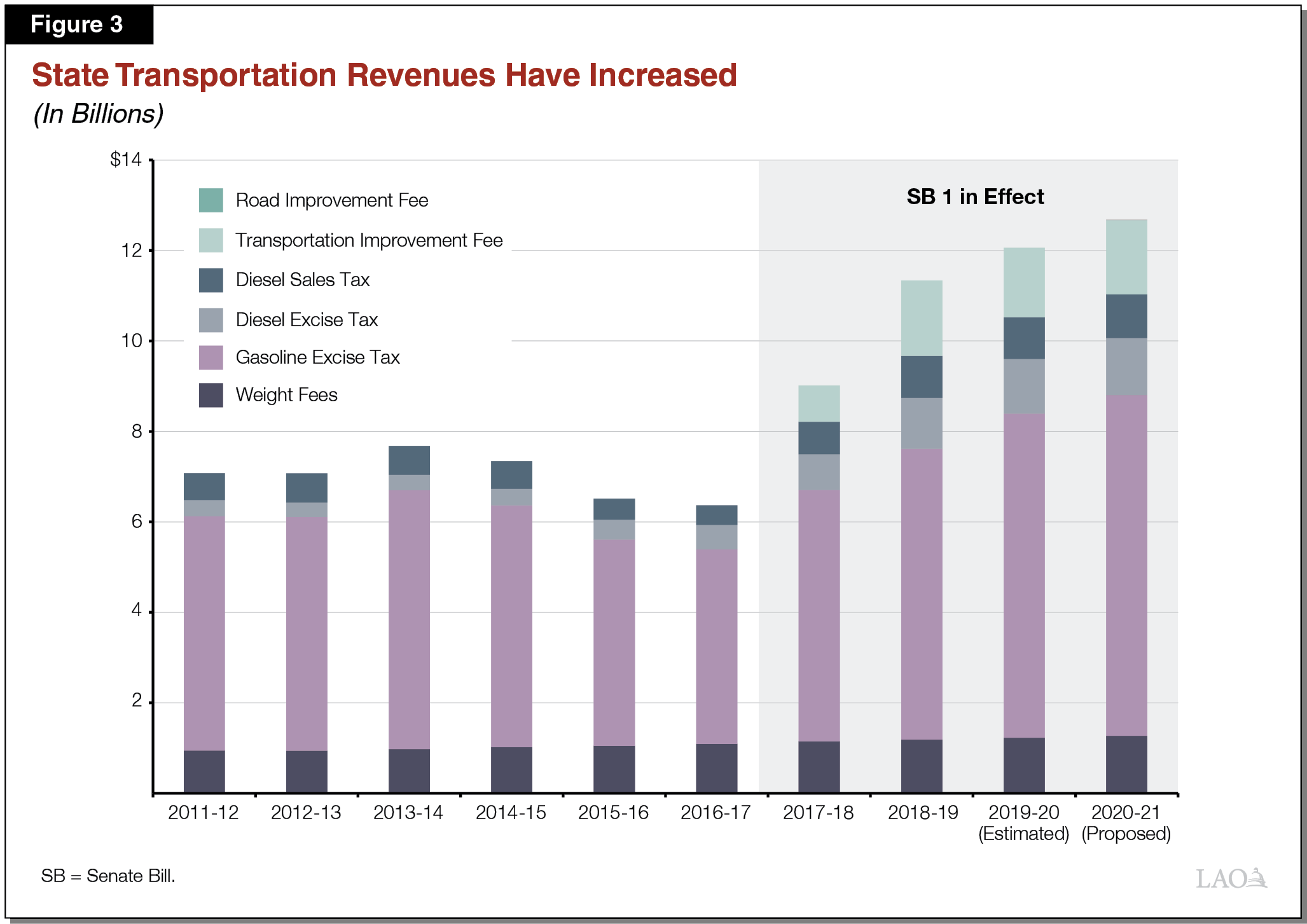

State Transportation Revenues Doubled Since SB 1. In 2017, the Legislature enacted Chapter 5 (SB 1, Beall), which increased various fuel taxes and vehicle fees that support California’s transportation system, particularly state highways, local streets and roads, and transit. (Senate Bill 1 did not change vehicle registration or driver license fees that primarily support CHP and DMV.) Since the enactment of SB 1, state revenue collected from fuel taxes and vehicle fees has grown from $6.4 billion in 2016‑17 to a projected $12.7 billion in 2020‑21. This includes an estimated increase of $626 million (5 percent) from 2019‑20 to 2020‑21.

A Few Proposals to Implement New or Recently Enacted Policy Changes

CHP—E‑Cigarette Tax Enforcement. The Governor’s budget includes $7 million in ongoing funding to form a task force led by CHP to investigate the manufacturing, transportation, distribution, and sales of illicit vaping devices. The Governor proposes to fund the task force with a new tax on vaping products. Given the number of illnesses and deaths attributed to illicit vaping products in recent years, it is reasonable for the Governor and the Legislature to be concerned and want to address this potentially growing public health problem. However, it is unclear whether the Governor’s proposal would be the most effective approach. To the extent the Legislature would like to direct more resources towards combatting illicit vaping products, we recommend that it consider various questions as it develops its preferred policy approach. These questions include: (1) what is the scope of the problem, (2) what are the most effective approaches, (3) what level of resources is appropriate, (4) what is the appropriate fund source, and (5) who should lead the effort?

DMV—Motor Voter Workload. The Governor’s budget includes an additional $6.4 million in 2020‑21 ($4.1 million ongoing) from the General Fund to support 38 new positions for the Motor Voter program. Although it is clear that the program requires additional ongoing resources, it is unclear whether the proposed positions and funds would fully address the workload because DMV (1) is currently in the process of implementing changes to improve workflow efficiency that would likely impact the level of staffing needed and (2) will be meeting a federal processing requirement in the upcoming primary election for the first time since implementing workflow improvements. Therefore, we recommend the Legislature withhold action on the request until later in the spring when additional information might be available to determine the appropriate staffing level.

HSRA—Administrative Cap. The budget reflects a change in HSRA’s approach to calculating the administrative cap allowed under Proposition 1A (2008). (The measure set the cap at 2.5 percent of bond proceeds, but allows the Legislature to raise it to up to 5 percent by statute.) Under its revised approach, HSRA will have an inconsistent method for how it categorizes state and contract staff who perform similar functions. HSRA estimates its revised approach to calculating the administrative cap will result in HSRA reaching the cap roughly three years later than previously anticipated (2023‑24 rather than 2020‑21). This is important because it delays a natural opportunity for legislative oversight. We recommend that the Legislature direct HSRA to apply the same approach to calculating the administrative cap for state staff and contractors.

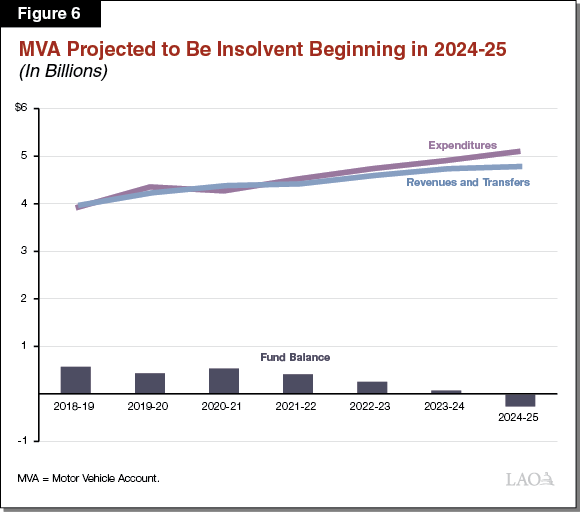

Certain Proposals Appear Warranted, but May Benefit From Legislative Oversight

Motor Vehicle Account (MVA) Fund Condition. Over the last several years, the MVA has periodically faced operational shortfalls—meaning planned expenditures exceed combined revenues and transfers. The proposed budget includes a few proposals intended to benefit the MVA in recognition of future operational shortfalls, including (1) shifting some costs to other funds and (2) using lease revenue bonds—rather than the typical “pay‑as‑you‑go” approach—to fund the construction phase of CHP and DMV facility projects. While the Governor’s budget proposals would help alleviate the operational shortfalls in the MVA over the next few years, they would not fully address the account’s structural imbalance. Absent any corrections, the administration projects that the MVA would have an operational shortfall of $228 million in 2024‑25, resulting in a negative fund balance of roughly $265 million. The Legislature will want to establish its priorities for the MVA and determine how best to address the projected insolvency based on these priorities.

Caltrans—Litter Abatement. The Governor proposes an increase of $31.8 million in 2020‑21 (growing to $43.4 million in 2024‑25 and ongoing) from the State Highway Account (SHA) to augment funding for the Litter Abatement Program. Given the likelihood that worsening litter conditions will continue, we recommend that the Legislature approve the Governor’s proposal to increase funding for the program. We also recommend the Legislature adopt supplemental reporting language requiring Caltrans to provide an assessment of the causes of increasing litter on state highways to inform future litter prevention strategies.

Caltrans—Pedestrian and Bicycle Safety. The budget includes $2.2 million on a two‑year, limited‑term basis from SHA to establish the Pedestrian and Bicyclist Safety Investigation Program. We find that providing additional resources to concentrate efforts on investigating pedestrian and bicycle collisions is reasonable given what appears to be a growing problem and, therefore, recommend approval of the budget request. In addition, we recommend the Legislature adopt supplemental reporting language requiring the department to report on its efforts to investigate and reduce pedestrian and bicycle fatalities.

Overview of Governor’s Transportation Budget

The state provides funding for six transportation departments: the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), the High‑Speed Rail Authority (HSRA), the California Highway Patrol (CHP), the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV), the California Transportation Commission, and the Board of Pilot Commissioners. The California State Transportation Agency (CalSTA) has jurisdiction over these six departments and is responsible for coordinating the state’s transportation policies and programs. In addition, the state provides funding to local governments for transportation purposes through “shared revenues” for local streets and roads and the State Transit Assistance program.

Total Proposed Spending of $26.9 Billion. Figure 1 shows the Governor’s proposed spending for the state’s transportation departments and programs from all fund sources—special funds, federal funds, reimbursements, bond funds, and the General Fund. In total, the Governor’s budget proposes $26.9 billion in expenditures for 2020‑21. This is a net increase of $3.4 billion (14 percent) over estimated expenditures for the current year. The increase mainly reflects increased spending on (1) highway projects administered by Caltrans and (2) the high‑speed rail project, as well as a shift in when funding for certain Caltrans mass transportaion projects will be allocated.

Figure 1

Transportation Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

Change From 2019‑20 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Department/Program |

|||||

|

Department of Transportation |

$11,408 |

$13,502 |

$15,486 |

$1,983 |

15% |

|

Local Streets and Roads |

2,538 |

2,881 |

3,003 |

122 |

4 |

|

High‑Speed Rail Authority |

878 |

1,100 |

2,911 |

1,810 |

165 |

|

California Highway Patrol |

2,546 |

2,788 |

2,712 |

‑76 |

‑3 |

|

Department of Motor Vehicles |

1,240 |

1,415 |

1,387 |

‑28 |

‑2 |

|

State Transit Assistance |

948 |

904 |

976 |

72 |

8 |

|

California State Transportation Agency |

346 |

904 |

406 |

‑498 |

‑55 |

|

California Transportation Commission |

6 |

9 |

12 |

3 |

29 |

|

Board of Pilot Commissioners |

3 |

3 |

3 |

— |

‑3 |

|

Totals |

$19,914 |

$23,508 |

$26,895 |

$3,387 |

14% |

|

Fund Source |

|||||

|

Special funds |

$13,551 |

$15,689 |

$19,333 |

$3,645 |

23% |

|

Federal funds |

4,560 |

6,401 |

5,582 |

‑819 |

‑13 |

|

Reimbursements |

794 |

936 |

1,336 |

400 |

43 |

|

Bond funds |

976 |

375 |

628 |

253 |

67 |

|

General Fund |

33 |

107 |

16 |

‑91 |

‑85 |

|

Totals |

$19,914 |

$23,508 |

$26,895 |

$3,387 |

14% |

Most Funding From Special and Federal Funds. As shown in the figure, most of the proposed funding for transportation—$24.9 billion (93 percent)—is from special funds and federal funds. Specifically, the proposed budget assumes $19.3 billion in special funds (such as revenues from fuel taxes, vehicle registration fees, and driver license fees) and $5.6 billion in federal funds for transportation purposes. Only $16 million (less than 1 percent) is proposed from the General Fund.

Transportation Bond Debt Service. In addition to the department and program expenditures identified in Figure 1, the state also pays debt service costs on transportation‑related general obligation bonds. For 2020‑21, the budget assumes about $2 billion in spending on debt service for these bonds—$166 million (9 percent) higher than the estimated current‑year level. (We note that this spending relates to repaying bonds issued primarily to fund expenditures made in prior years.) Most of the proposed spending is to repay (1) Proposition 1B (2006) bonds that support various highway, local road, and transit projects and (2) Proposition 1A (2008) bonds for the high‑speed rail project. Funding for debt service primarily comes from truck weight fee revenues.

Cross Cutting Issues

Update on SB 1 Revenue

In 2017, the Legislature enacted Chapter 5 (SB 1, Beall), to increase funding for California’s transportation system. Below we (1) provide background on SB 1, (2) discuss provisions taking effect in 2020‑21, and (3) present an update on revenue increases since its enactment.

Background

Transportation Funding Comes From a Variety of Sources. Funding for California’s transportation system comes from numerous local, state, and federal sources. State funding mainly comes from several fuel taxes and vehicle fees. The revenue from these taxes and fees fund transportation programs that provide for the operation, maintenance, and improvement of the State Highway System (SHS), inter‑city rail services, and other state‑owned transportation assets. The state also shares a portion of this revenue with local governments to support maintenance and improvements of streets and roads, as well as for transit infrastructure and operations.

SB 1 Increased Fuel Taxes and Vehicle Fees. The Legislature passed SB 1 to augment declining transportation revenue and to address the backlog of deferred maintenance within the state’s transportation system. Among other changes, SB 1 increased the existing excise taxes on gasoline, as well as the excise and sales taxes on diesel. The legislation also created two new annual vehicle registration fees: (1) the transportation improvement fee, which varies based on the value of a vehicle and (2) the road improvement fee for zero‑emission vehicles (ZEVs) model year 2020 and later. Figure 2 summarizes these taxes and fees and indicates their implementation date. Additionally, the legislation requires inflationary adjustments for the new transportation fees and for the fuel excise taxes—both those previously existing and those added under SB 1.

Figure 2

SB 1 Increased Several Taxes and Fees

|

Old Rates |

New Ratesa |

Effective Date |

|

|

Fuel Taxesb |

|||

|

Gasoline |

|||

|

Base excise |

18 cents |

30 cents |

November 1, 2017 |

|

Swap excise taxc |

11.7 cents |

17.3 cents |

July 1, 2019 |

|

Diesel |

|||

|

Excisec |

16 cents |

36 cents |

November 1, 2017 |

|

Sales |

1.75 percent |

5.75 percent |

November 1, 2017 |

|

Vehicle Feesd |

|||

|

Transportation improvement fee |

— |

$25 to $175 |

January 1, 2019 |

|

Road improvement (ZEV) fee |

— |

$100 |

July 1, 2020 |

|

aAdjusted for inflation starting July 1, 2020 for the gasoline and diesel excise taxes, January 1, 2020 for the Transportation Improvement Fee, and January 1, 2021 for the ZEV registration fee. The diesel sales taxes are not adjusted for inflation. bExcise taxes are per gallon. cVariable rates were set annually by the Board of Equalization based on estimated gasoline and diesel prices to maintain revenue neutrality. SB 1 converted both taxes to a fixed rate (exluding inflation adjustments). dPer vehicle per year. ZEV = zero‑emission vehicle. |

|||

New Provisions Go Into Effect in the Budget Year

The implementation of SB 1was phased in over multiple years. Revenue estimates for the upcoming fiscal year reflect the implementation of the road improvement fee and the first inflationary adjustments to the excise taxes on gasoline and diesel.

Road Improvement Fee. Starting July 1, 2020, ZEVs model year 2020 and later will be charged an annual $100 registration fee. The fee will be placed on battery‑electric and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. The fee is intended to account for the fact that ZEV owners benefit from the use of state highways and local streets and roads but otherwise do not contribute to their maintenance through the gasoline tax. The administration estimates that the new fee will generate $10.9 million in 2020‑21. All revenue collected from the road improvement fee will be deposited into the Road Maintenance and Rehabilitation Account (RMRA), which primarily funds maintenance on state highways and local streets and roads.

Inflationary Adjustments to Fuel Taxes. The state will begin indexing the excise taxes on gasoline and diesel for inflation on July 1, 2020. (Inflationary adjustments for the Transportation Improvement Fee began January 1, 2020.) Prior to SB 1, the fuel excise taxes were not subject to inflationary adjustments, which consequently led to transportation revenue diminishing in value over time. The gasoline and diesel excise taxes will be adjusted each fiscal year to reflect the percentage change in the California Consumer Price Index (CPI). However, in accordance with SB 1, the adjustments in 2020‑21 will reflect the past two years. The administration currently estimates that the gasoline and diesel excise taxes will increase by 3 cents per gallon and 2.2 cents per gallon, respectively. Our office estimates that the inflation adjustments are expected to increase transportation revenue by roughly $500 million. The additional revenue from the inflation rates will be allocated on existing statutory formulas.

Transportation Revenue Increases From SB 1

Total Transportation Revenues Doubled Since SB 1. As shown in Figure 3 (see next page), since the enactment of SB 1, transportation revenue collected by the state has significantly increased, growing from $6.4 billion in 2016‑17 to a projected $12.7 billion in 2020‑21. This includes an estimated increase of $626 million in 2020‑21, a 5 percent increase from 2019‑20.

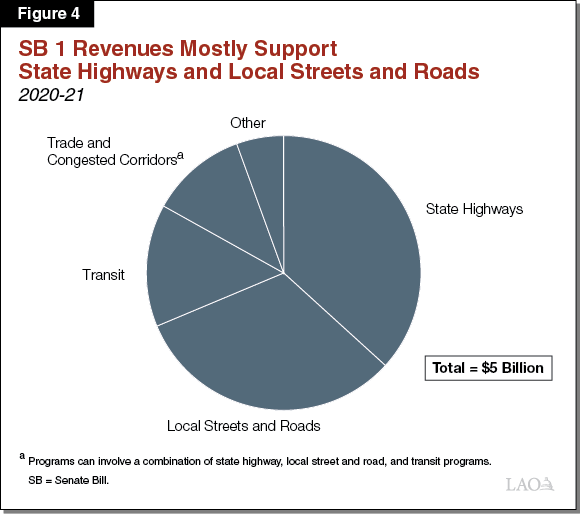

SB 1 Revenue Distributed Mostly to Highways and Streets and Roads. The administration estimates that SB 1 has resulted in $5 billion in additional revenue since 2016‑17. In most cases, this revenue is distributed according to formulas established in the legislation. Figure 4 (see next page) shows the administration’s SB 1 spending estimates for 2020‑21 by program area. A majority of the revenue is dedicated to maintaining and rehabilitating state highways and local streets and roads, while a smaller portion is directed towards improving the state’s major corridors and supporting transit programs. The remainder primarily funds active transportation, local planning grants, and university research on transportation policy.

Motor Vehicle Account (MVA) Fund Condition

The MVA supports the state administration and enforcement of laws regulating the operation and registration of vehicles used on public roads and highways, as well as the mitigation of the environmental effects of vehicle emissions. During the last several years, concerns about the condition of the MVA have arisen as spending from the account has, on occasion, grown faster than revenues. Below, we (1) provide background information on MVA revenues and expenditures, (2) describe the Governor’s proposals related to the MVA, (3) assess the condition of the MVA, and (4) identify issues for legislative consideration.

Background

MVA Revenues. The MVA receives most of its revenues from vehicle registration fees. As shown in Figure 5, the MVA is expected to receive a total of $4.2 billion in revenues in 2019‑20, with vehicle registration fees accounting for $3.5 billion (83 percent). Vehicle registration fees currently total $86 for each registered vehicle. (We note that the DMV also collects various other fees at the time of registration that are not deposited into the MVA, such as vehicle license fees, truck weight fees and an additional registration fee specifically for ZEVs.) The current $86 registration fee consists of two components:

- Base Registration Fee ($60). The state charges a base registration fee of $60, with $57 going to the MVA and $3 going to two other special funds—the Alternative and Renewable Fuel and Technology Fund ($2), and the Enhanced Fleet Modernization Subaccount ($1). (Under existing state law, the $3 charge included in the base registration fee to support the two other funds is scheduled to sunset on January 1, 2024.) The state last increased the base registration fee in 2016 when it increased the fee by $10 (from $46 to $56). At the same time, the state indexed the fee to CPI, thereby allowing it to automatically increase with inflation. The inflation adjustment for 2019 increased the fee to the current $60.

- CHP Fee ($26). The state also charges an additional fee of $26 that directly supports CHP. The state last increased this fee in 2014 when it increased the fee by $1 (from $23 to $24) and indexed it to the CPI. The inflation adjustment for 2019 increased the fee to the current $26.

The MVA also receives revenues from driver license fees. These revenues tend to fluctuate based on the number of licenses renewed each year. For 2019‑20, the state is expected to collect $382 million from these fees. The current driver license fee is $36 and is also indexed to the CPI. The remaining MVA revenues primarily come from late fees associated with vehicle registration and driver license renewals, identification card fees, and miscellaneous fees for special permits and certificates (such as fees related to the regulation of automobile dealers and driver training schools).

Figure 5

Motor Vehicle Account Fund Condition

(In Millions)

|

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

|

|

Beginning Reserves |

$532 |

$569 |

$433 |

|

Revenues and Transfers |

|||

|

Revenues |

|||

|

Registration fee |

$3,415 |

$3,535 |

$3,672 |

|

Other fees |

628 |

682 |

695 |

|

Total Fee Revenues |

$4,043 |

$4,217 |

$4,366 |

|

Transfers |

|||

|

Transfers to other funds |

‑$93 |

— |

— |

|

Total Resources |

$4,482 |

$4,785 |

$4,799 |

|

Expenditures |

|||

|

Baseline Support Expenditures |

|||

|

California Highway Patrol |

2,296 |

2,451 |

2,449 |

|

Department of Motor Vehicles |

1,184 |

1,351 |

1,318 |

|

California Air Resources Board |

148 |

153 |

152 |

|

Supplemental pension payments |

— |

124 |

64 |

|

Other costs |

278 |

263 |

265 |

|

Subtotals, Support |

($3,906) |

($4,342) |

($4,248) |

|

Capital Outlay Expenditures |

|||

|

California Highway Patrol |

$4 |

$8 |

$16 |

|

Department of Motor Vehicles |

3 |

2 |

5 |

|

Subtotals, Capital Outlay |

($7) |

($10) |

($21) |

|

Expenditure Totals |

$3,913 |

$4,352 |

$4,269 |

|

Fund Balance |

$569 |

$433 |

$530 |

MVA Transfers. The use of most MVA revenues are limited by the California Constitution to the administration and enforcement of laws regulating the use of vehicles on public highways and roads, as well certain transportation uses. However, roughly $90 million of the miscellaneous MVA revenue sources are not limited by constitutional provisions and, thus, are available for broader purposes. In order to help address the state’s General Fund condition at the time, the Legislature transferred these miscellaneous revenues from the MVA to the General Fund in 2009‑10 on a one‑time basis. A similar transfer was also made on a year‑by‑year basis in the next couple years, until it was approved as ongoing beginning in 2012‑13. However, due to the condition of the MVA in 2019‑20, the Legislature suspended these transfers to the General Fund for five years.

MVA Expenditures. The MVA primarily provides funding for three state departments—CHP, DMV, and the Air Resources Board (ARB)—to support the activities authorized in the California Constitution. Funding supports staff compensation, department operations, and capital expenses. For 2019‑20, a total of $4.4 billion is expected to be spent from the MVA, mostly to support CHP and DMV. Unlike for CHP and DMV, a relatively small share of ARB’s total expenditures is supported by the MVA.

Over the past several years, expenditures from the MVA have increased. Specifically, from 2014‑15 to 2019‑20, total MVA expenditures increased by $1 billion. Some of the major cost drivers include (1) replacement of CHP area offices and DMV field offices, (2) increased employee compensation costs, and (3) workload related to the issuance of new driver licenses and ID cards that comply with federal standards—commonly referred to as “REAL IDs.”

In addition, we note that supplemental pension plan repayments from the MVA began in 2019‑20. This is related to a 2017‑18 budget action to borrow $6 billion from the General Fund to make a one‑time supplemental payment to the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), which would be repaid from all funds that make employer contributions to CalPERS—including the MVA. (Over the next 30 years, it is anticipated that the MVA is likely to receive savings that outweigh these near‑term loan repayment expenditures, due to slower growth in employer pension contributions.)

Operational Shortfalls in Recent Years. Over the last several years, the MVA has periodically faced operational shortfalls—meaning planned expenditures exceeding combined revenues and transfers. For example, the MVA faced an operational shortfall in 2015‑16 of about $300 million, which was addressed through the one‑time repayment of $480 million in loans that were made previously from the MVA to the General Fund. In 2016‑17, the MVA faced an operational shortfall of roughly the same magnitude and possible insolvency in 2017‑18. In order to address this shortfall and help maintain the solvency of the MVA, the Legislature increased revenues into the account by increasing the base registration fee by $10 in 2016 and indexing it to the CPI (as discussed above).

Despite these earlier changes, more recent projections have the MVA becoming insolvent—meaning the fund would have a negative balance—in 2020‑21. In order to address this problem, the Legislature made several changes to reduce expenditures and transfers from the MVA as part of the 2019‑20 budget package. These changes included funding CHP area office replacements with lease revenue bonds, shifting certain one‑time MVA expenditures to the General Fund, delaying certain CHP and DMV capital outlay projects, delaying supplemental pension plan repayments to the General Fund, and suspending transfers to the General Fund. Despite these corrective actions, the administration projects the account to again experience an operational shortfall in 2021‑22 and become insolvent in 2024‑25.

Governor’s Proposals

While the administration projects that MVA revenues will exceed expenditures in the budget year, the proposed budget includes a few proposals intended to benefit the MVA in recognition of future operational shortfalls. (As we discuss below, the Governor’s budget also includes two proposals to increase MVA expenditures.) Specifically, the budget proposes to:

- Shift Administrative Costs for Collecting TIF to RMRA. The Transportation Improvement Fee (TIF) is collected by the DMV during vehicle registrations, transfers, and renewals. TIF revenue is used to repair infrastructure and provide road maintenance. Currently, the administrative costs for collecting TIF are funded by the MVA. However, the Governor’s budget proposes to fund these costs from the RMRA. Under the Governor’s proposal, this would reduce MVA costs by $6.6 million annually beginning in 2020‑21.

- Shift CalSTA Funding to the State Highway Account and Public Transportation Account. CalSTA develops and coordinates the policies and programs of the state’s transportation entities. To fund their work, the agency receives their funding from the departments and boards they oversee, including DMV and CHP. The Governor’s budget proposes to shift $3 million in CalSTA funding from the MVA to the State Highway Account (SHA) and the Public Transportation Account (PTA) annually beginning in 2020‑21.

- Shift From “Pay‑As‑You‑Go” to Financing for CHP and DMV Facilities. The state has typically funded the replacement of CHP area offices and DMV field offices from the MVA on a pay‑as‑you go basis. However, given the condition of the MVA last year, the Legislature shifted from pay‑as‑you‑go funding to lease revenue bonds to finance the replacement of CHP area offices. The Governor’s budget proposes to continue to finance the replacement of three CHP area offices through the Public Buildings Construction Fund, rather than with pay‑as‑you‑go as they were approved by the Legislature in prior years. In addition, the administration proposes to finance the replacement of three DMV field offices with lease revenue bonds. The financing of the projects would be repaid from the MVA over many years. Under the Governor’s proposal, shifting to lease‑revenue bonds is estimated to save the MVA a total of $176 million in the budget year. (We describe the specific proposals in the “California Highway Patrol” and the “Department of Motor Vehicles” sections of this report.)

MVA Projected to Become Insolvent in 2024‑25

While the Governor’s budget proposals would help alleviate the operational shortfalls in the MVA over the next few years, they would not fully address the account’s structural imbalance. Specifically, the Department of Finance’s five‑year projection (2020‑21 through 2024‑25) estimates that the MVA’s fund balance will be depleted by 2024‑25—resulting in insolvency. These projections reflect expenditures already approved by the Legislature and those proposed by the Governor (such as those described above).

Figure 6 compares total MVA resources (revenues and transfers) with expenditures from 2018‑19 through 2024‑25. As shown in the figure, absent any corrections, the administration projects that the MVA would face an operational shortfall of $228 million in 2024‑25, resulting in a negative fund balance of roughly $265 million. While expenditures are expected to exceed revenues in years prior to 2024‑25, available reserves would help prevent the fund from becoming insolvent sooner.

We note that the Governor’s forecast of the MVA fund condition assumes the future adoption of two proposals that would increase MVA expenditures in 2021‑22 and beyond. Specifically, the forecast assumes additional annual costs for CHP dash cams ($14 million) and DMV operational improvements for customer service, communication, training, management, and technology ($86 million, which would decrease to $34 million annually beginning in 2023‑24).

While the administration does not project insolvency until 2024‑25, various cost pressures could impact the solvency of the MVA, potentially resulting in insolvency occurring sooner. For example, the actual costs of DMV operational improvements might be higher than currently estimated if workload related processing to REAL ID applications is more than expected in future years. In addition, the increased employee cost could be higher than assumed.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

The Legislature will want to establish its priorities for the MVA and determine how best to address the projected insolvency based on these priorities. While the MVA is not projected to become insolvent until 2024‑25, we recommend the Legislature begin to take steps now to prevent the insolvency. While the Governor’s budget proposals would help improve the condition of the MVA, there are alternatives, as well as additional steps that could be taken. We note that to the extent the Legislature rejects the Governor’s proposed changes for 2020‑21, the MVA would become insolvent beginning in 2023‑24—a year sooner than under the Governor’s plan—with a negative fund balance of roughly $147 million.

In developing its plan for addressing the projected insolvency of the MVA, the Legislature will want to consider the impacts on the MVA beyond the administration’s forecast period of the next five years. For example, the condition of the fund has shaped both the DMV’s and CHP’s approach to capital outlay expenditures. Both departments have aging facilities with safety, structural, and size deficiencies. However, due to the condition of the MVA, the administration is proposing to fund only one new facility replacement or renovation project per year for each department. CHP has 111 total offices, and DMV has 172 field offices. The current rate of replacing or reconfiguring these aging facilities is not likely to be sufficient over the longer term and could affect the ability of these departments to fulfill their responsibilities as effectively as possible.

In order to assist the Legislature in developing its plan and mix of strategies for addressing the MVA’s condition—both in the near and long term, we identify the following options for its consideration:

- Delay Supplemental Pension Plan Repayments. The Legislature could delay the supplemental pension plan repayments from the MVA that began in 2019‑20. The administration’s MVA projections account for these annual payments, which are estimated to moderately grow from $64 million in 2020‑21 to $75 million in 2024‑25. While delaying these loan payments would increase costs when they are eventually made, it would provide immediate relief to the MVA until then. (Under current law, the principal and interest of the loan must be repaid by June 30, 2030.) This could be particularly beneficial to accommodate some of the increased cost pressures on the MVA that are not ongoing, such as the increased workload associated with the implementation of REAL ID.

- Eliminate General Fund Transfer. As mentioned earlier, the MVA receives roughly $90 million of the miscellaneous revenues that are not limited in their use by the California Constitution. In 2019‑20, the Legislature suspended transfers of these revenues to the General Fund for five years in order to keep these revenues in the MVA, particularly given that these funds were initially transferred by the Legislature on a temporary basis to help address the state’s General Fund condition at the time. The Legislature could eliminate such transfers on an ongoing basis to provide an additional $106 million in 2024‑25 to support MVA expenditures.

- Increase MVA Revenues. The Legislature could generate additional revenues by increasing vehicle registration or driver license fees—either on a limited‑term or ongoing basis. In determining whether to increase such fees, the Legislature will want to consider the potential fiscal impacts on drivers and vehicle owners. We estimate that roughly $35 million in additional revenue could be generated annually from a $1 increase in the base vehicle registration or CHP fee, and roughly $5 million from a $1 increase in the driver license fee. Given the magnitude of the future operation shortfalls in the MVA, if the Legislature wanted to increase existing DMV fees, it would need to do so by a significant amount or in combination with other actions.

- Reduce Operational Costs. As mentioned earlier, increasing employee compensation is one of the key cost pressures to the MVA. The Legislature could reduce employee compensation costs from the MVA by reducing the number of positions at DMV and CHP; however, such actions would result in a decrease in the level of service. Going forward, the Legislature also might want to consider the impact of employee compensation costs on the overall MVA fund condition when it evaluates future memoranda of understanding negotiated between the administration and the employee unions that represent the majority of DMV and CHP employees.

Caltrans

Caltrans is responsible for planning, coordinating, and implementing the development and operation of the state’s transportation system. The department operates and maintains state highways, supports three inter‑city rail routes, and distributes state and federal funds for local transportation projects.

The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $15.5 billion for Caltrans in 2020‑21. This is $2 billion, or 15 percent, higher than the estimated current‑year expenditures. Figure 7 (see next page) shows proposed expenditures by program and fund source. Most spending supports the department’s highway program and comes from various state special funds (fuel taxes and vehicle fees) and federal funds. The increase mostly reflects additional revenue from SB 1 (see our analysis of SB 1 revenues earlier in this report), as well as from a shift in when Caltrans expects funding for certain mass transportation projects to be allocated. The total level of spending proposed for Caltrans in 2020‑21 supports about 20,800 positions.

Figure 7

Caltrans Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Actual |

Estimated |

Proposed |

Change From 2019‑20 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Program |

|||||

|

Highways |

|||||

|

Capital outlay projects |

$4,309 |

$4,934 |

$5,022 |

$89 |

2% |

|

Local assistance |

1,677 |

2,716 |

3,245 |

529 |

19 |

|

Capital outlay support |

1,881 |

2,194 |

2,206 |

12 |

1 |

|

Maintenance |

2,218 |

2,115 |

2,138 |

23 |

1 |

|

Other |

492 |

504 |

509 |

5 |

1 |

|

Subtotals |

($10,578) |

($12,463) |

($13,121) |

($657) |

(5%) |

|

Mass transportation |

$547 |

$717 |

$2,047 |

$1,330 |

185% |

|

Other |

283 |

322 |

318 |

‑4 |

‑1 |

|

Totals |

$11,408 |

$13,502 |

$15,486 |

$1,983 |

15% |

|

Fund Source |

|||||

|

Special funds |

$6,215 |

$6,397 |

$8,714 |

$2,318 |

36% |

|

Federal funds |

4,417 |

6,218 |

5,436 |

‑782 |

‑13 |

|

Reimbursements |

641 |

799 |

1,195 |

396 |

50 |

|

Bond funds |

136 |

77 |

141 |

63 |

81 |

|

General Fund |

— |

12 |

— |

‑12 |

— |

|

Totals |

$11,408 |

$13,502 |

$15,486 |

$1,983 |

15% |

Litter Abatement

Background

Increase in Highway Litter. Caltrans removes litter within the state highway right of way to maintain traffic safety, protect water quality, and provide clean facilities for travelers and local communities. In recent years, the department has experienced a growing litter issue. The amount of litter collected by the department has increased by roughly 77 percent over that past four years. The number of service requests for litter abatement have increased from about 3,800 in 2014‑15 to 5,300 in 2018‑2019—a 40 percent increase. The department projects that the number of service requests and amount of trash collected will continue to increase over the next several years.

Expenditure Increase on Contracted Litter Abatement. Litter removal is conducted by Caltrans employees, the Adopt‑A‑Highway Program, and the Litter Abatement Program. The Litter Abatement Program generally uses cooperative agreements with state agencies—such as the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation—and local law enforcement to utilize inmates and probationers for litter abatement services. As the need for litter abatement has increased on the SHS, Caltrans has redirected resources from its overall maintenance budget to increase the capacity of the Litter Abatement Program. The department’s expenditure levels on the program have increased by $39 million (62 percent) from 2014‑15 to 2018‑2019—from $63 million to $102 million.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor proposes an increase of $31.8 million in 2020‑21 (growing to $43.4 million in 2024‑25 and ongoing) from the SHA to augment funding for the Litter Abatement Program. The department states that the proposed increase is to reflect the current level of spending on the program with some adjustments to meet the anticipated level of litter in future years.

Assessment

Increasing Litter Abatement Resources Is Reasonable. Department data clearly demonstrates that the volume of trash on the state highway system has risen significantly over the past four years, resulting in significant additional litter abatement workload. In response, the department has increased its expenditure on the Litter Abatement Program by roughly $39 million. Given the multiyear trend, it seems likely that these conditions will persist and possibly worsen. Therefore, it is reasonable for the department’s budget to reflect an increased level of spending on the program.

Causes of Growing Litter Issue Are Unclear. Based on our conversations with Caltrans, the department lacks sufficient information to identify the causes contributing to increased litter on state highways. Having such information could assist the state in finding effective strategies to prevent litter in the long run. While increased funding for litter abatement is an interim solution, doing so comes with some opportunity cost. Specifically, spending more SHA funds on litter abatement leaves less funding for other transportation programs. Identifying effective strategies to reduce litter in the longer run could help ensure that as much funding as possible is preserved for these other programs.

Recommendation

Approve Funding for Litter Abatement and Require Assessment. Given the likelihood that current litter conditions will continue, we recommend that the Legislature approve the Governor’s proposal to increase funding for the department’s Litter Abatement Program. We also recommend the Legislature adopt supplemental reporting language requiring Caltrans to provide an assessment to inform future litter prevention strategies. This assessment should identify, to the extent possible, (1) the type of litter being left on state highways, (2) the source of litter, (3) the degree to which increases in litter are concentrated in certain geographical regions, (4) best practices to reduce litter from other states, and (5) potential recommendations to prevent litter on the SHS.

Pedestrian and Bicyclist Safety Investigations

Background

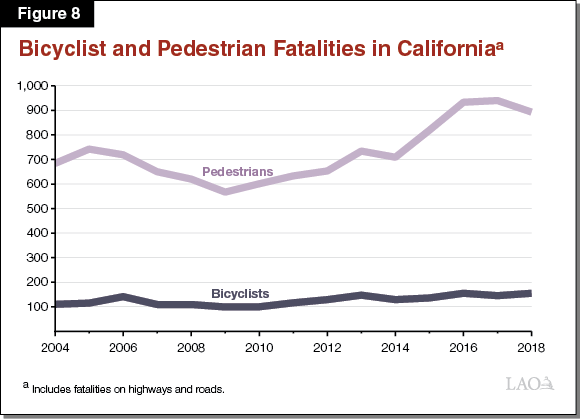

Pedestrians and Bicyclists Made Up a Fifth of All Highway Fatalities. According to Caltrans, pedestrians and bicyclists made up 21 percent of all fatalities on the SHS between 2008 and 2017. Across all highways and roads in California, pedestrians and bicyclists made up approximately 29 percent of the fatalities in 2018. Moreover, the number of pedestrians and bicyclists fatalities on highways and roads has grown significantly in recent years. As show in Figure 8, between 2004 and 2018, pedestrian fatalities grew by 31 percent and bicyclist fatalities grew by 41 percent. (At the time of this writing, Caltrans had not provided annual historic information regarding the number of fatalities specifically on the SHS.)

Caltrans’ Traffic Operations Program Addresses Safety Concerns on State Highways. To improve traffic safety on the SHS, Caltrans currently has five traffic safety programs that investigate high‑collision areas, develop safety measures, and implement proposed improvements. These programs focus on different types of collisions, such as wrong way collisions and collisions where vehicles run onto the shoulder. In recent years, Caltrans—in collaboration with UC Berkeley—implemented two pilot programs to improve safety for pedestrians and bicyclists. These pilot programs identified locations on the highway with high concentrations of pedestrian and bicyclist deaths and injuries based on historical data, investigated these locations to determine probable cause of the deaths and injuries, and recommended capital and maintenance projects to improve pedestrian and bicyclist safety.

Governor’s Proposal

The budget includes $2.2 million on a two‑year, limited‑term basis from the SHA to establish the Pedestrian and Bicyclist Safety Investigation Program. The proposal would fund 12 transportation engineers who are expected to perform a total of 400 investigations of collisions involving pedestrians and bicyclists. Each investigation is expected to require 54 hours to complete. In addition, district staff would receive training on appropriate investigation techniques and development of countermeasures for pedestrian and bicyclist collisions.

Assessment

Proposal to Expand Pedestrian and Bicyclist Safety Investigations Is Reasonable. In total, the pilots identified almost 400 locations of pedestrian or bicyclist collisions on the SHS warranting investigation. Given the number of pedestrians and bicyclists fatalities on the SHS, as well as the trend of rising fatalities statewide, it is reasonable to dedicate additional resources to address pedestrian and bicyclist safety on the SHS. In addition, given that this is a new program, we find the request for limited‑term positions to be reasonable.

Uncertainty About Underlying Trends. While the request for expanding pedestrian and bicyclist safety investigations is reasonable, there is uncertainty about the underlying factors leading to the rising number of pedestrian and bicyclist fatalities. Caltrans reports that the department’s increasing use of pedestrian and bicyclist friendly design in their planning and construction might have led to increased use of the SHS by pedestrians and bicyclists, resulting in an accompanying increase of pedestrian and bicyclist fatalities. However, more pedestrian and bicyclists might be involved in fatal collisions for many reasons. For example, there may be more pedestrians on the SHS as a result of the growing number of homeless camps near highways.

Recommendation

Approve Proposal and Require Report. We recommend that the Legislature approve Caltrans’ request for two‑year limited term funding of $2.2 million from SHA. We find that providing additional resources to concentrate efforts on investigating pedestrian and bicycle collisions is reasonable given what appears to be a growing problem. In addition, we recommend the Legislature adopt supplemental reporting language requiring the department to provide a report by January 10, 2022, related to its efforts to investigate and reduce pedestrian and bicycle fatalities. Specifically, the report should include information on (1) the number of pedestrian and bicyclist traffic safety collisions, fatalities, and investigations conducted; (2) key findings or trends resulting from these investigations, including insights into the causes of the higher number of fatalities in recent years; (3) the traffic safety improvements made to the SHS as a result of these investigations; and (4) the implementation of the proposed training for district staff on appropriate pedestrian and bicyclist collision investigation techniques and development of countermeasures. This information would better allow the Legislature to review the effectiveness of the Pedestrian and Bicyclist Safety Investigation Program, which could then inform decisions regarding the appropriate level of ongoing resources for the safety programs, as well as other actions the state might take to reduce the number of collisions and fatalities.

Wildfire Litigation

Background

Caltrans Facing Lawsuit for Recent State Wildfire. Caltrans can be held financially liable for personal and property damages that are caused by the condition of the SHS. As part of its larger maintenance responsibility, Caltrans conducts vegetation control to reduce the risk of fire. The department indicates that it currently is facing a lawsuit related to a recent wildfire that started along a state highway. The lawsuit is expected to have a substantial number of plaintiffs and claims due to the large geographic area and number of properties affected by the wildfire.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor proposes an increase of $1.7 million for four years from the SHA to support the department’s legal division for anticipated workload increases stemming from the recent wildfire lawsuit. The department’s legal division is a full‑service litigation and in‑house counsel law office with statewide responsibility for Caltrans. The augmentation would support 14 new positions.

Assessment

Workload Likely to Increase From Wildfire Litigation. Given the scale of the suit, it is reasonable to expect the department’s legal division to have a significant amount of increased workload associated with the wildfire litigation. In our view, it is in best interest of the state to ensure Caltrans has sufficient resources to defend against the lawsuits given the large potential financial liability.

Low Service Scores for Tree and Brush Encroachment in Recent Years. Caltrans annually assesses its ability to service the SHS through level of service scores. Level of services scores range from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating a higher maintenance need. Scores are calculated at the district level, but are averaged to calculate overall statewide scores for various maintenance activities. The department’s level of services scores for tree and brush encroachment have been about 70 in recent years. In a recent report, the department stated its goal of increasing level of service scores for tree and brush encroachment to at least 90. We do not have any evidence that improper vegetation management contributed to the wildfire that is the subject of the recent lawsuit. However, Caltrans’ low scores for tree and brush encroachment are concerning, particularly given severe wildfires that have occurred in recent years, as well as projections of increased risks over the long term due to climate change. In recent years, the Legislature has taken actions in other policy areas—such as forest health and utility safety—in order to reduce wildfire risks. Monitoring the department’s efforts in achieving its level of service goal for tree and brush encroachment might be another area of wildfire risk worthy of additional legislative oversight.

Recommendations

Recommend Approving Funding for Wildfire Litigation. It appears likely that Caltrans will face increased workload associated with the recent wildfire litigation, and it is in the best interest of the state for the department to have sufficient resources to engage in the litigation effectively. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature approve the proposed $1.7 million to augment the department’s legal division.

Report at Budget Hearings on the Implementation of Vegetation Control. We also recommend that the Legislature use spring budget hearings as an opportunity to exercise additional oversight of Caltrans’ vegetation management activities by requiring the department to report at budget hearings on the following topics:

- Vegetation Management Plan. What are the department’s current vegetation management policies to reduce wildfire risk?

- Low Level of Service Scores. Why are level of service scores for tree and brush encroachment relatively low?

- Level of Service Score by Location. To what extent do level of service scores vary geographically, such as based on an area’s risk of wildfire?

- Steps to Improve Scores. What steps has the department taken (or plan to take) to improve level of service scores related to tree and brush encroachment?

Transportation System Network Replacement

Background

Transportation System Network Must Be Updated. The Transportation System Network (TSN) is an existing department database that is used to store collision and roadway data for the SHS. Recent federal laws require states to expand their safety data systems to identify fatalities and serious injuries on all public roads. Caltrans has indicated that the current TSN does not meet the new requirements and that the department will have to replace the existing system.

Information Technology (IT) Project Approval Process. The TSN replacement project is currently proceeding through the state’s IT project approval process known as the Project Approval Lifecycle (PAL). Departments cannot begin their projects without receiving approval from the California Department of Technology (CDT) for each of the four PAL stages. The TSN replacement project is in Stage 3 and is expected to complete Stage 4—project readiness and approval—in September 2020.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor requests $5.4 million (one time) from the SHA for the department to begin the implementation of the TSN replacement project—following approval of Stage 4 of the PAL process. The project will be completed in multiple phases across several years and will have an estimated total cost of $21.9 million. The requested funding will be used to support the first year of the TSN replacement project and for limited‑term staffing.

Assessment

Funding Being Proposed Prior to Completion of PAL Process. As noted above, CDT is expected to approve the proposed TSN replacement project through Stage 4 of the PAL process later this fall. Until that approval occurs, the Legislature does not have a complete project plan (including an approved scope, schedule, and cost for the proposed project) to consider alongside the budget request. Therefore, approving funding for Phase 1 of the proposed TSN replacement project at this point in the process comes with some uncertainty for the Legislature.

Recommendation

Approve Funding for TSN Replacement With Added Budget Bill Language. The replacement of the current TSN is necessary for the department to comply with federal law and to remain eligible for federal highway funding. For these reasons, the Legislature should approve funding for the proposed project. However, since the project has not completed the PAL process, we recommend the Legislature adopt provisional budget bill language to authorize these expenditures only upon CDT’s approval of the proposed project through Stage 4 of the PAL process, and upon written notification of the Joint Legislative Budget Committee with the complete project plan including the approved scope, schedule, and cost of the project.

Department of Motor Vehicles

The DMV is responsible for registering vehicles, issuing driver licenses, and promoting safety on California’s streets and highways. Additionally, DMV licenses and regulates vehicle‑related businesses (such as automobile dealers and driver training schools), and collects certain fees and taxes for state and local agencies. As of January 2020, there were 27.3 million licensed drivers and 35.8 million registered vehicles in the state.

The Governor’s budget includes $1.4 billion for DMV in 2020‑21, which is $28 million (about 2 percent) lower than the estimated level of spending in the current year. About 95 percent of all DMV expenditures are supported from the MVA, which generates its revenues primarily from vehicle registration and driver license fees. The level of spending proposed for 2020‑21 supports about 8,500 positions at DMV.

The Governor’s budget also continues recent efforts to replace DMV field offices that are too small or have structural problems. As shown in Figure 9, the budget includes a total of $54.7 million—from the Public Buildings Construction Fund and the MVA—for capital outlay projects, including continuation of four field office replacement and reconfiguration projects, as well as one new replacement project (San Francisco). While the state has typically funded the replacement of DMV facilities from the MVA on a pay‑as‑you‑go basis, the administration’s 2020‑21 budget proposes that the construction phase of capital projects be financed through the Public Buildings Construction Fund.

Figure 9

Department of Motor Vehicles Capital Outlay Projects

(In Thousands)

|

2020‑21 |

Phase |

Total Project Cost |

|

|

Santa Maria‑field office replacement |

$17,372 |

C |

$21,820 |

|

Reedley‑field office replacement |

17,354 |

C |

20,944 |

|

Delano‑field office replacement |

15,291 |

C |

18,003 |

|

San Francisco‑field office replacement |

2,905 |

PC |

5,126 |

|

Oxnard‑field office reconfiguration |

1,229 |

W |

13,537 |

|

Statewide‑planning and site identification |

500 |

A, S |

500 |

|

Totals |

$54,651 |

$109,930 |

|

|

C = construction; PC = performance criteria; W = working drawings; A = acquisition; and S = study. |

|||

Motor Voter Workload

Background

National Voter Registration Act (NVRA). Since 1993, the NVRA required states to offer individuals an opportunity to register to vote when they apply for a driver’s license or identification (DL/ID) card. Until 2015, the DMV complied with the federal law through a two‑step voter registration process. Every person who applied for or renewed a DL/ID card or submitted a change of address (COA) form received a voter registration card (VRC). To register to vote, individuals would have to submit the VRC to the DMV, who then forwards them to the Secretary of State (SOS) within ten days. However, if the VRC is submitted within five days of a voter registration deadline for an election, DMV must transmit the VRC to SOS within five days.

New Motor Voter Program. Chapter 729 of 2015 (AB 1461, Gonzalez) established the New Motor Voter Program (NMVP), which in addition to the federal requirements, required the DMV to electronically provide information related to voter registration for all eligible individuals to the SOS automatically. Under NMVP, all eligible individuals who apply for an original or renewal DL/ID card or submit a COA form at the DMV are automatically registered to vote, unless the person affirmatively declined to be registered to vote during the transaction.

Prior Funding for the New Motor Voter Program. DMV received one‑time and ongoing augmentations to implement Chapter 729 in 2016‑17, 2017‑18, and 2018‑19. This funding was intended to allow DMV to develop and implement an electronic DL/ID card application (NMVP application), as well as to process new voter registration‑related workload. Currently, DMV has baseline funding of $3.2 million from the General Fund for 12 positions to implement the NMVP. In addition to the baseline funding, DMV has been redirecting 50 positions to administer and process the workload associated with the NMVP.

Assessments of the New Motor Voter Program. Pursuant to a request by former Governor Brown in September 2018, the Department of Finance contracted with Ernest & Young (E&Y) for an independent technical assessment of the NMVP application, business processes, system development, risks, quality assurance, and data integration between SOS and DMV. The E&Y report provided recommendations on business process improvements concerning governance, oversight, accountability, quality management, and data validation. For example, the report recommended legal resources be assigned to the program to ensure compliance with federal, state, and other requirements. As a result, the DMV implemented improved quality assurance processes, provided legal and compliance resources, and established data governance policies.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget includes an additional $6.4 million in 2020‑21 ($4.1 million ongoing) from the General Fund to support NMVP. The administration’s proposal would support 38 new positions, including (1) 20 positions for registration operations to address the change of address and renewal by mail workload; (2) 7 positions for quality assurance review; (3) 9 IT support positions for maintenance, operations, and continuing improvement of the NMVP application; and (4) 2 positions for administration and oversight of the NMVP. The proposal also includes two‑year limited term funding for legal counsel to oversee compliance of the program, as well as funding for IT consultant services.

Assessment

Fewer Positions Than Currently Used. Although the Governor’s budget proposes additional ongoing positions to implement the NMVP, the number of requested positions is fewer than the number of positions currently supporting the program. The DMV has been redirecting 50 positions from other programs to support NMVP workload because the baseline positions have been insufficient to address all of the workload. Under the administration’s proposal, those staff positions would be returned to their usual work. Based on our conversations with the department, it is requesting fewer new positions than it has been redirecting because it assumes it can achieve some efficiencies in processing time. For example, DMV is currently implementing a more streamlined process to manage COA forms and eliminating duplicative tasks. However, these efficiencies have not been fully implemented yet, meaning there is potential risk that the number of positions needed for the NMVP may be more than what is being requested.

Federal Requirements Might Create Additional Workload. In recent months, DMV consistently has met the federal ten‑day requirement to provide voter information to SOS. However, it is unclear whether the department will consistently be able to meet the shortened time period required near the voter registration deadline. As mentioned earlier, the NVRA requires the DMV to send voter registration information to SOS in a shorter time period if the information is received within five days of the last day to register to vote for an election. For example, DMV requested $2.2 million from the General Fund in the current year for overtime and temporary help to meet the shortened time frames for this spring’s primary election. However, DMV’s 2020‑21 budget request does not include similar funds for overtime or temporary help for processing applications in the five‑day time frame for this fall’s general election.

Recommendation

Although it is clear that the NMVP requires additional ongoing resources, it is unclear whether the proposed positions and funds would fully address the workload. Therefore, we recommend the Legislature withhold action on the request until later in the spring when additional information might be available to determine the appropriate staffing level. DMV is currently implementing changes in programming to improve system and workflow efficiency that would likely impact the level of staffing needed. In addition, the voter registration deadline for the upcoming election is on February 18th, 2020. As a result, over the coming months, the DMV will have more information on the outcomes of the process improvements, as well as its success rate at meeting the 5‑day requirement. This information could help the Legislature determine the appropriate staffing levels for the NMVP.

San Francisco Field Office Replacement Project

Governor’s Proposal

The budget includes $2.9 million from the MVA for the performance criteria phase of the San Francisco field office replacement project. In total, the project is estimated to cost $35.1 million. DMV proposes to design the project to include features—which could include energy efficiency and on‑site generation capacity—so that the building will meet the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design silver rating criteria, as well as zero‑net energy (ZNE) requirements.

Assessment

Insufficient Evidence That Addition of ZNE Is Cost‑Effective for State. A building is ZNE if the total amount of energy used on an annual basis is no more than the amount of renewable energy created on the site. According to the administration, the state currently has 28 ZNE buildings. The administration proposes to construct the San Francisco field office replacement to be ZNE, a decision that is driven by the Governor’s Executive Order B‑18‑12, which calls for 50 percent of new facilities beginning design after 2020 to be ZNE. While we recognize that energy conservation can help reduce the state’s environmental impact and help it achieve its climate change‑related goals, DMV has not been able to provide analysis to substantiate the cost‑effectiveness of constructing the San Francisco field office projects as ZNE at this time. For example, it has not provided an estimate of the energy savings or other cost savings that are anticipated to be achieved by the project. Consequently, it is unclear if adding the ZNE requirement to this project is a good fiscal investment for the state. If this project were shown not to be cost‑effective, the state could accomplish more energy savings by investing in other projects—such as energy efficiency projects or solar photovoltaic projects—with the same funding.

Recommendation

Withhold Action Pending Additional Information. In view of the above, we recommend the Legislature withhold taking action on the proposed $2.9 million in MVA funds for the San Francisco field office until DMV reports at budget hearings on the cost‑effectiveness of constructing the project as ZNE. More specifically, we recommend the department provide the cost of constructing the project as ZNE, the cost savings associated with operating a ZNE building, and the estimated payback period. This information would help ensure that the Legislature has the best information available before deciding on the level of funds to authorize for the project.

If the department is unable to provide the additional information or the project is shown not to be cost‑effective, we recommend the Legislature direct the department to modify its request to exclude any ZNE‑related components that are not cost‑effective. Moving forward, we recommend the department provide cost‑effectiveness assessments for all proposed ZNE projects to allow the Legislature to make more informed fiscal investments in capital projects for the state.

California Highway Patrol

The primary mission of CHP is to ensure safety and enforce traffic laws on state highways and county roads in unincorporated areas. CHP also promotes traffic safety by inspecting commercial vehicles, as well as inspecting and certifying school buses, ambulances, and other specialized vehicles. The department carries out a variety of other mandated tasks related to law enforcement, including investigating vehicular theft and providing backup to local law enforcement in criminal matters. The operations of CHP are divided across eight geographic divisions throughout the state.

The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $2.7 billion in 2020‑21, primarily from the MVA. The total funding level proposed is about $76 million, or 3 percent, less than the revised current‑year estimate. The year‑over‑year net decrease is mainly the result of the expiration of one‑time funding provided in 2019‑20, including $87 million for the replacement of radio equipment and IT infrastructure.

The Governor’s budget also continues recent efforts to replace CHP field offices that are too small or have structural problems. As shown in Figure 10, the budget includes a total of $141.5 million—from the Public Buildings Construction Fund and the MVA—for various capital outlay projects. This includes funding to continue four area office replacement projects, as well as initiate one new area office replacement project (Gold Run).

Figure 10

California Highway Patrol Capital Outlay Projects

(In Thousands)

|

2020‑21 |

Phase |

Total Project Cost |

|

|

Santa Fe Springs‑office replacement |

$44,279 |

DB |

$46,226 |

|

Baldwin Park‑office replacement |

43,137 |

DB |

44,869 |

|

Quincy‑office replacement |

38,112 |

DB |

40,252 |

|

Enhanced radio system‑towers and vaults replacement |

10,208 |

C |

13,034 |

|

Humboldt‑office replacement |

2,107 |

A, PC |

44,197 |

|

Keller Peak‑tower replacement (reappropriation) |

1,819 |

C |

2,323 |

|

Gold Run‑office replacement |

1,370 |

A |

40,338 |

|

Statewide planning and site identification |

500 |

A,S |

500 |

|

Totals |

$141,532 |

$231,739 |

|

|

DB = design‑build; C = construction; A = acquisition; PC = performance criteria; and S = study. |

|||

E‑Cigarette Tax Enforcement

Background

Vaping Products Are Associated With Lung Injuries. Electronic cigarettes (e‑cigarettes) and other vaping devices allow users to inhale aerosol from a liquid solution that can contain nicotine, tetrahydrocannabinol (commonly known as THC), cannabidiol, or other substances. In 2019, vaping devices were associated with numerous lung injuries and deaths in the United States. In California, 204 patients have been hospitalized and four have died due to an e‑cigarette or vaping associated lung injury since 2019. Currently, federal and state authorities are investigating the cause of these illnesses. In particular, the use of illicit vaping devices—unregulated and untested products that are often sold by unlicensed retailers—appears to be associated with these illnesses. Because illicit vaping devices are not tested, these products can have added chemicals, pesticides, and other harmful ingredients.

State, Local, and Federal Agencies Enforce Laws and Regulations of Vaping Products. Nicotine vaping devices are regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The FDA establishes regulations concerning the manufacture, import, packaging, labeling, advertising, promotion, sale, and distribution of nicotine vaping devices. In California, the state’s Department of Justice (DOJ) has a Tobacco Litigation and Enforcement Section that administers and enforces state and federal tobacco laws, including enforcement against the unlawful sale of tobacco products.

For cannabis vaping devices, the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) regulates device manufacturers by setting health and safety standards. The Bureau of Cannabis Control (BCC) regulates the sales and distribution of cannabis products. In recent months, for example, BCC has investigated unlicensed retailers that sell illicit cannabis vaping products. At the federal level, the FDA along with the Drug Enforcement Agency conduct investigations into the manufacture, sale, and distribution of cannabis vaping devices across the country. Local law enforcement agencies also investigate illicit vaping devices, particularly cannabis products. (Under Proposition 64 [2016], which legalized adult use of cannabis in California, local governments may regulate and tax cannabis within their jurisdictions.) It is unclear what level of resources local law enforcement agencies currently are dedicating to the investigation and enforcement of illicit vaping products.

Governor’s Proposal

Creates New CHP‑Led Task Force to Investigate Illicit Vaping Devices. The Governor’s budget includes nine permanent positions and $7 million in ongoing funding to form a task force led by CHP to investigate the import, export, manufacturing, transportation, distribution, and sales of illicit vaping devices. Under the Governor’s proposal, a sergeant would oversee the statewide task force, which would be made up of eight officers, one in each CHP division office. The budget also includes funding for CHP to reimburse DOJ for the use of eight investigators who would assist CHP in its investigations.

Funds Task Force With Revenue From Proposed Tax on E‑Cigarettes. The Governor proposes to fund the task force with a new tax on vaping products. The new tax would begin on January 1, 2021, and would be $2 for each 40 milligrams of nicotine in the vaping product. The administration estimates the tax would generate $32 million in 2020‑21, which would be deposited into a new fund—the Electronic Cigarette Products Tax Fund. (The administration also proposes using the revenue to support the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration, which would be responsible for administering the tax.) According to the administration, it anticipates proposing an ongoing spending plan for the tax revenues next year with additional spending for tax administration, enforcement, youth prevention, and health care workforce programs.

Assessment

Given that illicit vaping products pose a legitimate public health issue, it is appropriate for the state to be proactive in addressing the issue. However, we find that the Governor’s proposal for a CHP‑led task force to investigate illicit vaping devices raises some concerns, which we describe below.

Scope of the Market for Illicit Vaping Devices Is Unclear. It is unclear how widespread illicit vaping devices are in California, in both magnitude and geography. There is uncertainty in the number and types of individuals or groups involved in the market for unregulated and untested vaping products, as well as whether such activity is taking place across the state or concentrated in particular regions. Under the proposal, the officers would be spread across the state, which may not be the most efficient distribution of positions if the problem is more regional than statewide. Moreover, the use of vaping devices is still relatively new and therefore, may be subject to change. It is possible that the outbreak of vaping associated lung injuries might result in a decrease in the demand for illicit vaping devices, resulting in users of vaping devices choosing to buy legal products, or to stop vaping altogether, due to health concerns. Therefore, the long‑term need for additional investigators is unclear and could change as consumer behavior changes in the coming years.

Enforcement Is One of Several Potential Strategies to Combat Illicit Vaping Devices. Investigations of illicit vaping devices might discourage the manufacture, distribution, and sales of illegal products, decreasing the supply of untested and unregulated vaping devices in the state. However, such enforcement activity is just one approach and does not address the demand for illicit vaping products. It is unclear what the most effective strategy or group of strategies is. Enforcement might be more effective when paired with other approaches to change the demand for these products, such as expanded consumer awareness campaigns and regulation of legal vaping devices. For example, the Governor signed an executive order in 2019, directing CDPH to allocate at least $20 million in tobacco and cannabis program funds for an anti‑vaping awareness campaign and to develop recommendations to limit availability of vaping products to youths under age 21.

Unclear CHP Is the Appropriate Entity to Lead Investigations of Illicit Vaping Products. CHP can investigate crimes related to illicit vaping devices, but it does not currently have any specific expertise in this area. Currently, CHP does not have a dedicated unit that specializes in investigating illicit tobacco or cannabis products. Furthermore, the department reports they have not yet conducted any investigations into illicit vaping devices. However, other departments, such as CDPH, BCC, and DOJ have prior expertise in regulating and enforcing laws concerning tobacco and cannabis products. In addition, many local regulatory and law enforcement agencies might have existing resources dedicated to investigating illicit tobacco and cannabis products in their communities.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

For the reasons described above, it is unclear whether the Governor’s proposal to create a CHP‑led investigative task force would be the most effective approach to addressing the problem of illicit vaping products. However, given the number of illnesses and deaths attributed to illicit vaping products in recent years, it is reasonable for the Governor and the Legislature to be concerned and want to implement strategies to address this potentially growing public health problem. To the extent the Legislature would like to direct more resources towards combatting illicit vaping products, we recommend that it consider the following questions as it develops its policy approach:

- What Is the Scope of the Problem? Currently, the problem of illicit vaping devices is poorly understood, both in terms of the size of the market and the extent to which the problem is geographically concentrated in some areas within California. To better understand the issue, the Legislature might want to consider providing resources to study the scope of the problem, which could better inform how best to target enforcement or other strategies.

- What Are the Most Effective Approaches? This proposal focuses on enforcement as an approach to addressing the problem of illicit vaping products. However, the Legislature might want to consider the degree to which it wants to rely on a law enforcement approach as compared to focusing on consumer awareness, implementation of regulations, or some combination of approaches.

- What Level of Resources Is Appropriate? The Legislature could appropriate more or less funding than proposed in the Governor’s budget depending on how it prioritizes this issue, as well as what approach it wants to take to address the problem.

- What Is the Appropriate Fund Source? The administration proposes to fund the task force with a new tax on vaping products. However, it currently is unclear whether the Legislature will approve this new tax. In the case that the proposed tax is rejected and addressing the illicit vaping problem remains a priority, the Legislature could consider using other fund sources, such as the General Fund or one of the various tobacco and cannabis‑related funds.

- Who Should Lead the Effort? It is not clear that CHP currently has the most expertise to lead an anti‑illicit vaping effort. Other state and local entities might be better suited to lead a coordinated effort due to their existing roles and responsibilities related to tobacco and cannabis law enforcement, product regulation, public health and education.

High‑Speed Rail Authority

Chapter 796 of 1996 (SB 1420, Kopp) established the High‑Speed Rail Authority (HSRA) to plan and construct a high‑speed rail system that would link the state’s major population centers. HSRA is governed by a nine‑member board appointed by the Legislature and Governor. In addition, HSRA is led by an executive director appointed by the board. In November 2008, voters approved Proposition 1A, which specified certain conditions that the system must ultimately achieve, as well as authorized the state to sell bonds to partially fund the system and various local projects that will facilitate high‑speed rail.