LAO Contacts

- Ross Brown

- Climate Change

- Energy Commission

- Rachel Ehlers

- Fish and Wildlife

- Water Resources

- Shawn Martin

- Toxic Substances

- Conservation

- Jessica Peters

- Forestry and Fire Protection

- Parks

February 25, 2020

The 2020-21 Budget

Resources and Environmental Protection

- Overview of Governor’s Budget

- Crosscutting Issues

- Department of Parks and Recreation

- California Department of Fish and Wildlife

- Department of Water Resources

- Department of Toxic Substances Control

- Department of Conservation

- California Energy Commission

- Capital Outlay and Bond Administration

- Summary of Recommendations

Executive Summary

In this report, we assess several of the Governor’s budget proposals in the natural resources and environmental protection areas. Based on our review, we recommend various changes, as well as areas that would benefit from additional legislative oversight. In this summary, we describe our major findings and recommendations. We provide a complete listing of our recommendations at the end of this report.

In addition, our office has published two separate reports that include assessments and recommendations related to natural resources and environmental protection programs. The 2020‑21 Budget: Climate Change Proposals reviews four proposals by the Governor related to climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts: (1) the cap‑and‑trade expenditure plan ($965 million), (2) climate‑related research and technical assistance ($25 million), (3) a Climate Catalyst Revolving Loan Fund ($250 million), and (4) a climate bond ($4.8 billion). The 2020‑21 Budget: Wildfire‑Related Proposals reviews 22 different proposals related to wildfire prevention, mitigation, and response, including for the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection and the California Natural Resources Agency. This report includes a brief summary of the key recommendations from each of these reports.

Budget Provides $11 Billion for Programs

The Governor’s budget for 2020‑21 proposes a total of $11.4 billion in expenditures from various fund sources for programs administered by the California Natural Resources ($7.1 billion) and Environmental Protection ($4.3 billion) Agencies. The budget plan for these programs reflects a net reduction of $1 billion (8 percent) compared to the current‑year budgeted level. While there is a net reduction in overall spending authority, the proposed budget is mostly consistent with what was approved for the current year and generally does not reflect significant programmatic reductions. Instead, the overall net spending reduction largely reflects the appropriation of one‑time funding in the current year. For example, the current‑year budget provides natural resources and environmental protection departments over $600 million more in one‑time bond funds from Proposition 68 (2018) than is proposed for the budget year.

Budget Includes Several Significant Fiscal and Policy Proposals

New Oversight Board for Department of Toxic Substances Control (DTSC). The Governor’s budget plan includes $3 million from the General Fund for two years to establish a Board of Environmental Safety to oversee DTSC, as well as perform specified responsibilities. We recommend that the Legislature authorize the establishment of a new oversight board in order to improve transparency and promote greater accountability of DTSC. However, if it chooses to authorize a board, the Legislature will want to closely evaluate the different options for the board’s structure and responsibilities to ensure that they align with legislative priorities. For example, the Legislature may wish to consider how much authority the board should have to direct DTSC’s day‑to‑day operations.

New Fee Structure for DTSC. The Governor’s budget includes two sets of changes to address structural deficits in the Toxic Substances Control Account (TSCA) and Hazardous Waste Control Account (HWCA)—two funds that support DTSC. First, the budget plan includes one‑time General Fund transfers totaling $13 million to address the structural deficits in the budget year. Second, the Governor proposes budget trailer legislation to restructure various charges that support the two funds on an ongoing basis. We recommend the Legislature wait to take action on the Governor’s proposal to transfer General Fund to TSCA and HWCA until the May Revision when updated information about the funds’ conditions will be available. We further recommend the Legislature decide whether to establish a Board of Environmental Safety before weighing the merits of the Governor’s proposals to restructure charges for TSCA and HWCA. The Legislature may wish to consider whether the Governor’s budget trailer legislation to adjust TSCA and HWCA would (1) create a charge structure that would cover the costs of both the departments’ existing mandated functions and potential program expansions, and (2) reflect the “polluter pays” principle.

Purchase of a New State Park. The Governor’s budget includes $20 million from the General Fund on a one‑time basis to acquire land to create a new state park. The proposal lacks numerous critical details, such as the properties the department is considering to create the new park, metrics that will be used to select a property, and potential future costs to build‑out and maintain the park. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature require the administration to provide additional information on the proposal. Based on the information provided, the Legislature may wish to approve, modify, or reject the proposal based on how the proposal aligns with legislative budgetary and programmatic priorities.

Funding Enhancements for California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW). The Governor proposes $19 million ongoing from the General Fund—transferred from the Habitat Conservation Fund and Wildlife Conservation Board—and $20 million one time from the General Fund to help CDFW better meet its mission, primarily for activities to protect fish and wildlife. While we find that the proposed activities have merit, funding for the ongoing activities would be shifted from other state conservation programs. We recommend the Legislature adopt the one‑time $20 million funding proposal because the resources will be used to make certain department operations and maintenance activities more efficient. We further recommend the Legislature weigh the relative trade‑offs of the ongoing $19 million proposal with its other conservation and General Fund priorities. Lastly, we recommend deferring action on a third component of the Governor’s proposal—to extend funding scheduled to expire in 2021‑22—until next year when a more in‑depth analysis of CDFW’s budget will be available.

Overview of Governor’s Budget

In this section, we provide an overview of the Governor’s 2020‑21 budget plan for the state’s natural resources and environmental protection departments, including a brief description of the main changes from the current year. Later in this report, we provide more detailed assessments of many of these specific proposals.

Overall Plan Mostly Similar to Current Year

Total Spending of $11.4 Billion Proposed. California’s Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Agencies oversee the activities of about 40 state departments, boards, and conservancies whose missions are to protect and restore the state’s natural resources and to ensure public health and environmental quality. The Governor’s 2020‑21 budget proposes total funding of $11.4 billion from all sources—the General Fund, as well as special, bond, and federal funds—for these entities. As shown in Figure 1, this reflects a net reduction of $1 billion (8 percent) compared to the current‑year budgeted level. (Later in this section, we compare proposed spending to revised estimates for the current year, which have been updated since the enactment of the budget.)

Figure 1

Proposed Spending Compared to 2019‑20 Budgeted Level

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Agency |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

Change |

|

|

Amount |

Percent |

|||

|

Natural Resources |

$7,429 |

$7,095 |

‑$334 |

‑4% |

|

Environmental Protection |

5,007 |

4,313 |

‑694 |

‑14 |

|

Totals |

$12,436 |

$11,408 |

‑$1,028 |

‑8% |

Net Reduction Mostly Reflects One‑Time Funding in Current Year. While there is a net reduction in overall spending authority, the proposed budget is mostly consistent with what was approved for the current year and generally does not reflect significant programmatic reductions. Instead, the overall net spending reduction largely reflects the appropriation of one‑time funding in the current year. For example, the current‑year budget provides natural resources and environmental protection departments over $600 million more in one‑time bond funds from Proposition 68 (2018) than is proposed for the budget year. Partially offsetting these reductions, the proposed 2020‑21 budget also includes various proposals for increased funding. We summarize the most significant proposed budget adjustments later in this section.

Summary of Natural Resources Budget Changes

Total of $7.1 Billion Proposed for Natural Resources Departments. As shown in Figure 2, the Governor’s budget plan for entities within the California Natural Resources Agency (CNRA) includes a total of $7.1 billion. Almost half of this funding (including most of the General Fund support) is for the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire) and debt service on past natural resources‑related general obligation bonds. More than half of the total for natural resources departments is proposed to be funded from the General Fund, with the remainder mostly from special funds and bond funds. Of the total proposed, $5.4 billion (76 percent) is to administer state programs, and most of the remainder is for local assistance—generally grants to local governments and nonprofits to implement projects.

Figure 2

Natural Resources Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

Change From 2019‑20 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Total |

$7,286 |

$9,423 |

$7,095 |

‑$2,327 |

‑25% |

|

By Department |

|||||

|

Forestry and Fire Protection |

$2,220 |

$1,902 |

$2,019 |

$117 |

6% |

|

General obligation bond debt service |

988 |

1,089 |

1,310 |

221 |

20 |

|

Parks and Recreation |

1,172 |

1,041 |

1,029 |

‑11 |

‑1 |

|

Water Resources |

746 |

2,317 |

973 |

‑1,344 |

‑58 |

|

Fish and Wildlife |

538 |

560 |

573 |

13 |

2 |

|

Energy Commission |

370 |

867 |

455 |

‑412 |

‑48 |

|

Conservation Corps |

137 |

172 |

137 |

‑35 |

‑21 |

|

Conservation |

138 |

146 |

136 |

‑10 |

‑7 |

|

Natural Resources Agency |

353 |

484 |

130 |

‑353 |

‑73 |

|

State Lands Commission |

103 |

85 |

61 |

‑24 |

‑28 |

|

Wildlife Conservation Board |

196 |

195 |

48 |

‑147 |

‑75 |

|

Other resources programsa |

324 |

565 |

223 |

‑342 |

‑61 |

|

By Funding Source |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$3,771 |

$3,933 |

$3,906 |

‑$28 |

‑1% |

|

Special funds |

1,594 |

2,313 |

1,792 |

‑521 |

‑23 |

|

Bond funds |

1,645 |

2,887 |

1,106 |

‑1,781 |

‑62 |

|

Federal funds |

277 |

288 |

291 |

3 |

1 |

|

By Purpose |

|||||

|

State operations |

$5,261 |

$5,684 |

$5,423 |

‑$261 |

‑5% |

|

Local assistance |

1,795 |

2,620 |

1,356 |

‑1,264 |

‑48 |

|

Capital outlay |

231 |

1,119 |

316 |

‑803 |

‑72 |

|

aIncludes state conservancies, Coastal Commission, and other departments. |

|||||

Key Changes for Natural Resources Departments. Compared to updated estimates of current‑year expenditures, proposed 2020‑21 spending for natural resources departments is lower by $2.3 billion (25 percent). This reduction largely reflects the expiration of one‑time funding provided in the 2019‑20 Budget Act, as well as technical budget adjustments made since enactment of the budget, rather than significant programmatic changes.

- General Fund. On net, General Fund spending for natural resources entities is proposed to decrease by $28 million (1 percent). This decrease reflects a number of one‑time, current‑year appropriations, including about $170 million provided for various local assistance projects administered by CNRA or the Department of Parks and Recreation. The budget also includes significant General Fund increases, including (1) an additional $221 million in debt service costs to repay previously approved, natural resources‑related general obligation bonds and (2) roughly $120 million for CalFire to enhance wildfire staffing and other resources. (The Governor’s budget also reflects a reduction of roughly $220 million from the General Fund in both the current and budget years for the Emergency Fund, which is used to support certain costs associated with fighting wildfires.)

- Bond Funds. The Governor’s budget provides $1.8 billion less for bond funded activities and projects than estimated for the current year. As noted above, some of this reflects a net reduction in funds provided from Proposition 68—over $400 million compared to the current‑year budget—for natural resources programs. In addition, much of this apparent budget‑year decrease is related to how certain bonds are accounted for in the budget, making year‑over‑year comparisons difficult. Specifically, bonds that were appropriated but not spent in prior years are often carried over to the current year. The 2019‑20 amount will be adjusted in the future based on actual expenditures.

Summary of Environmental Protection Budget Changes

Total of $4.3 Billion Proposed for Environmental Protection Departments. As shown in Figure 3, the Governor’s budget plan for entities within the Environmental Protection Agency includes a total of $4.3 billion. Most of this supports three departments—the California Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery (CalRecycle), California Air Resources Board (CARB), and State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB). Of the total budgeted, $3.8 billion (88 percent) is proposed to be funded from special funds, and $2.6 billion (59 percent) is for local assistance.

Figure 3

Environmental Protection Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

Change From 2019‑20 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Total |

$8,014 |

$5,552 |

$4,313 |

‑$1,240 |

‑22% |

|

By Department |

|||||

|

Resources Recycling and Recovery |

$3,584 |

$2,102 |

$1,589 |

‑$512 |

‑24% |

|

Air Resources Board |

1,759 |

1,422 |

1,139 |

‑284 |

‑20 |

|

Water Resources Control Board |

2,242 |

1,528 |

1,093 |

‑435 |

‑28 |

|

Toxic Substances Control |

282 |

335 |

325 |

‑10 |

‑3 |

|

Pesticide Regulation |

103 |

114 |

114 |

— |

— |

|

Other departmentsa |

45 |

52 |

53 |

1 |

1 |

|

By Funding Source |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$2,176 |

$676 |

$143 |

‑$533 |

‑79% |

|

Special funds |

4,284 |

4,101 |

3,783 |

‑318 |

‑8 |

|

Bond funds |

1,191 |

406 |

18 |

‑388 |

‑96 |

|

Federal funds |

364 |

370 |

369 |

— |

— |

|

By Purpose |

|||||

|

State operations |

$3,611 |

$2,216 |

$1,757 |

‑$459 |

‑21% |

|

Local assistance |

4,403 |

3,336 |

2,556 |

‑781 |

‑23 |

|

Capital outlay |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

aIncludes the Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, and general obligation bond debt service. |

|||||

Key Changes for Environmental Protection Departments. Compared to updated estimates of current‑year expenditures, proposed 2020‑21 spending for environmental protection departments is lower by $1.2 billion (22 percent). Similar to natural resources departments, this reduction largely reflects the expiration of one‑time funding provided in the 2019‑20 Budget Act, as well as technical budget adjustments.

- General Fund. The proposed budget reflects a significant net reduction in General Fund—$533 million (79 percent)—compared to the current year. However, this mostly reflects one‑time costs for CalRecycle to conduct debris cleanup activities following recent wildfires, as well as for funding provided in the current year to accelerate cleanup of lead contamination near the Exide battery recycling facility.

- Special Funds. Special fund expenditures are estimated to decrease by $318 million (8 percent). The biggest change affecting this spending is the Governor’s cap‑and‑trade expenditure plan, which decreases the allocation to CARB by almost $200 compared to the current‑year budget.

- Bond Funds. The Governor’s budget provides $388 million (96 percent) less for bond‑funded activities and projects than estimated for the current year. This largely reflects a reduction of over $200 million provided from Proposition 68 for SWRCB. Similar to what is described for natural resources bonds, much of this apparent budget‑year decrease is related to how certain bonds are accounted for in the budget.

Budget Includes Several Significant Fiscal Proposals

Figure 4 lists the most significant budget‑year funding changes proposed for natural resources and environmental protection departments. Most of the funding increases are proposed as one time or limited term. (The figure does not include year‑over‑year changes in allocations of cap‑and‑trade auction revenues to various programs.)

Figure 4

Significant Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Budget Changes

(In Millions)

|

Proposal |

2020‑21 Amount |

Fund Source |

|

Forestry and Fire Protection |

||

|

Fire protection: relief staffing |

$93 |

Mostly GF |

|

Fire protection: mobile equipment replacement |

19 |

GF |

|

Fire protection: direct mission support |

17 |

Mostly GF |

|

Various air attack base infrastructure projects |

14 |

GF |

|

Emergency Fund adjustment |

‑219 |

GF |

|

Department of Water Resources |

||

|

Systemwide flood risk reduction projects |

$96 |

BF |

|

Urban flood risk—American River project |

46 |

GF |

|

Sustainable groundwater management |

40 |

GF |

|

Tijuana River project |

35 |

GF |

|

New River Improvement Project |

28 |

GF, BF |

|

Natural Resources Agency |

||

|

LiDAR data |

$80 |

GF |

|

Conservation Corps |

||

|

Residential Center—Ukiah |

$62 |

BF |

|

Energy Commission |

||

|

ARFVTF expenditures |

$51 |

SF |

|

Department of Parks and Recreation |

||

|

New state park |

$20 |

GF |

|

Outdoor environmental education grant |

20 |

GF |

|

Museum storage facility |

15 |

BF |

|

Department of Fish and Wildlife |

||

|

Funding enhancements |

$39 |

GF, SF |

|

State Water Resources Control Board |

||

|

Cannabis program |

$23 |

SF |

|

Department of Conservation |

||

|

Oil and gas oversight |

$14 |

SF |

|

Department of Toxic Substances Control |

||

|

Base funding to maintain operations |

$13 |

GF |

|

GF = General Fund; BF = bond funds; LiDAR = light detection and ranging; ARFVTF = Alternative and Renewable Fuel and Vehicle Technology Fund; and SF = special funds. |

||

Crosscutting Issues

Climate Change Proposals

Major Proposals Related to Climate Change Mitigation and Adaption. The Governor’s budget includes four major proposals related to climate mitigation and/or adaptation—(1) the cap‑and‑trade expenditure plan ($965 million), (2) expanded funding for climate‑related research and technical assistance ($25 million), (3) establishment of the Climate Catalyst Revolving Loan Fund ($250 million), and (4) a climate bond ($4.8 billion). Our recent report, The 2020‑21 Budget: Climate Change Proposals, includes a description of each proposal, our assessment, and associated recommendations.

Key Issues to Consider. There are a variety of important considerations that the Legislature will want to weigh as it constructs a climate change package that best reflects its priorities and achieves its goals effectively. Notably, the Governor proposes a significant increase in the amount of General Fund resources allocated to climate‑related activities, including significant out‑year General Fund commitments to pay off the proposed bond. We urge the Legislature to think broadly about its priorities and the role of the General Fund, Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF), and other funds—as well as nonfinancial tools, such as regulatory programs—in achieving its climate goals. Some of the key considerations when developing an overall approach include:

- Is the overall spending amount consistent with legislative priorities, considering the potential need and the wide variety of other potential uses of the funds?

- How does the Legislature want to prioritize funding for adaptation versus mitigation? As part of that evaluation, the Legislature might want to consider the past and current levels of spending for each type of activity, as well as the relative merits of relying on funding to achieve these goals versus other strategies, such as regulations.

- How should funds be allocated in order to most effectively achieve the Legislature’s climate goals? Programs that receive funding should (1) have clearly defined goals and objectives, (2) be well coordinated across different government entities, (3) address clear market failures and complement regulatory programs, and (4) have effective strategies and resources for evaluating future outcomes.

Recommendations. We summarize our recommendations on each of the proposals in Figure 5. Overall, the Governor’s approach includes some positive steps intended to help reduce climate change risks, including additional focus on adaptation activities. In many cases, however, the Legislature could consider modifications to the proposals that might better reflect its priorities and achieve its climate goals more effectively. In one case—the proposed Climate Catalyst Revolving Loan Fund—we find that the administration has not provided adequate justification to merit adoption, though the Legislature could consider creating a pilot program to gauge the type and number of appropriate projects that might qualify for the program.

Figure 5

Summary of LAO Recommendations

|

Cap‑and‑Trade Expenditure Plan |

|

|

|

|

|

Climate Research and Technical Assistance Funding |

|

|

|

Climate Catalyst Loan Fund |

|

|

|

Climate Bond |

|

|

|

|

Wildfire Proposals

In recent years, California has experienced some of the deadliest and most destructive wildfires in the state’s history. While wildfires have always been a natural part of California’s ecosystems, recent increases in the severity of wildfires and the adverse impacts on communities have increased the focus on the state’s ability to effectively prevent, mitigate, and respond to wildfire risks. In our recent report The 2020‑21 Budget: Governor’s Wildfire‑Related Proposals we assess: (1) the state’s overall approach to addressing wildfire risks and (2) the Governor’s wildfire‑related budget proposals that involve multiple departments. In this section, we summarize the findings and recommendations from our recent report as they relate to natural resources departments.

State Should Develop Strategic Wildfire Plan to Address Risks. In assessing the state’s overall approach to addressing wildfire risks, we find that several factors contribute to increasing risks, including increased development in fire‑prone areas, unhealthy forestlands, climate change, and the role of utility infrastructure management. In the coming decades, the state will likely continue to face demands for additional funding and resources to respond to wildfire risks. Yet, without a broad and comprehensive evaluation of wildfire risks and mitigation strategies, it will be difficult for the Legislature to efficiently and effectively allocate additional funding related to wildfires. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature require the development of a statewide strategic wildfire plan. The purpose of the plan would be to inform and guide state policymakers regarding the most effective strategies for responding to wildfires and mitigating wildfire risks. In particular, this would include guidance on the highest‑priority and most cost‑effective programs and activities that should receive funding, as well as an assessment of how the state can achieve an optimal balance of funding for prevention and mitigation activities with demands to increase fire response capacity.

Governor’s Wildfire‑Related Budget Proposals. The Governor’s budget provides a total of $492 million (mostly from the General Fund) for 22 proposals for wildfire‑related augmentations across multiple natural resources and other departments. The total includes $179 million for CalFire, $119 million jointly for CalFire and the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services, $80 million for CNRA, and $210,000 for the Forest Management Task Force.

Based on our review, we classify the budget proposals in three categories. Specifically, we find (1) that even in the absence of a strategic plan, some proposals appear reasonable; (2) several proposals are promising but lack important implementation details; and (3) some proposals raise more significant concerns because they might not align with some of the key elements we think should be included in a strategic wildfire plan, they lack basic workload justification, or both. Figure 6 summarizes the wildfire‑proposals for natural resources departments and our recommendations for each proposal.

Figure 6

Summary of Natural Resources Wildfire Proposals and Recommendations

|

Proposal |

Description |

Recommendations |

|

Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire) |

||

|

Relief staffing |

$93.4 million mostly General Fund in 2020‑21 (increasing to $142.6 million ongoing) to support 294 positions in 2020‑21 (increasing to 555 positions ongoing) for (1) additional firefighting staff, (2) increased training academy staff, and (3) 14 fire engines for training purposes. |

|

|

Various capital outlay projects |

$39.4 million General Fund for new capital outlay projects ($11.9 million) and to continue previously approved projects ($27.5 million). New projects include replacing two helitack bases, a conservation camp, and an auto shop. |

|

|

Mobile equipment replacement |

$19 million General Fund for two years to replace CalFire vehicles and mobile equipment. |

|

|

Direct mission support—administrative staffing |

$16.6 million ongoing ($10.8 million General Fund and $5.8 million reimbursements) to support 103 administrative positions. |

|

|

Wildland firefighting research grant |

$5 million one‑time General Fund to fund firefighting research related to protective equipment and safety. |

|

|

Hired equipment staffing |

$2.9 million General Fund in 2020‑21 ($2.4 million ongoing) to support ten positions to operate a program to contract for firefighting equipment from private vendors. |

|

|

Mobile equipment staffing |

$1.7 million General Fund in 2020‑21 ($1.5 million ongoing) to support nine positions related to processing and procurement of vehicles and mobile equipment. |

|

|

Building standards and defensible space education—SB 190 |

$689,000 Building Standards Administration Special Revolving Fund to support two positions for the Office of the State Fire Marshall to implement provisions of SB 190 related to defensible space inspections and fire safety building standards training. |

|

|

CalFire and Office of Emergency Services Joint Proposals |

||

|

Home hardening pilot program—AB 38 |

$110.1 million—including (1) $100 million one time ($75 million federal funds and $25 million General Fund); (2) $8.3 million in 2020‑21 GGRF (decreasing to $6.1 million ongoing); and (3) $1.8 million General Fund (decreasing to $1.6 million annually for next four years)—to implement AB 38. Provides 33 positions. Includes establishing a $100 million home hardening grant program, conducting defensible space inspections related to real estate transactions, training defensible space inspectors, hiring mobile equipment positions, and purchasing a new fire engine. |

|

|

Wildfire Forecast and Threat Intelligence Integration Center—SB 209 |

$9 million General Fund and PUCURA (decreasing to $6.3 million ongoing) to establish a weather forecasting intelligence and integration center required by SB 209. |

|

|

Other Entities |

||

|

Light detection and ranging data (LiDAR) (CNRA) |

$80 million one‑time General Fund to contract for the collection of LiDAR data of the entire state. |

|

|

Administration and research support (Forest Management Task Force) |

$210,000 ongoing Environmental License Plate Fund to support two positions to conduct various workload required by executive order. |

|

|

SB 190 = Chapter 404 of 2019 (SB 190, Dodd); AB 38 = Chapter 391 of 2019 (AB 38, Wood); GGRF = Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund; SB 209 = Chapter 405 of 2019 (SB 209, Dodd); PUCURA = Public Utilities Commission Utilities Reimbursement Account; and CNRA = California Natural Resources Agency. |

||

Department of Parks and Recreation

The state park system, administered by the Department of Parks and Recreation (Parks), contains 280 parks and serves about 75 million visitors each year. State parks vary widely by type and features, including state beaches, museums, historical sites, and ecological reserves. The size of each park also varies, ranging from less than one acre to 600,000 acres. In addition, parks offer a wide range of amenities—including campsites, golf courses, ski runs, visitor information centers, tours, trails, fishing and boating opportunities, restaurants, and stores. Parks also vary in the types of infrastructure they maintain, including buildings, roads, power generation facilities, and water and wastewater systems.

For 2020‑21, the Governor’s budget proposes $1 billion in total expenditures—including $213 million from the General Fund—for the department. More than half of the department’s proposed budget supports state park operations, with most of the remainder for local assistance grant programs. The proposed budget is $11 million (1 percent) lower than the estimated current‑year spending level for Parks. This decrease largely reflects the net effect of certain one‑time funding provided in the current year—particularly for the development of the Native American Heritage Center and grants for various local park projects—offset by various funding increases proposed in the 2020‑21 budget.

New State Park

The Governor’s budget includes $20 million (one time) to acquire land to create a new state park. The proposal lacks numerous critical details, such as the properties the department is considering to create the new park, metrics that will be used to select a property, and potential future costs to build‑out and maintain the park. We recommend that the Legislature require Parks to provide additional information on the proposal. Depending on the information provided, the Legislature may wish to approve, modify, or reject the proposal.

Background

Parks regularly acquires land to augment existing state parks. Less frequently in recent years, the department establishes a new state park. The department has acquired properties for four new state parks in the past 19 years—including Los Angeles State Historic Park (2001), Fort Ord Dunes State Park (2009), the California Indian Heritage Center State Park (2011), and Onyx Ranch State Vehicular Recreation Area (2014). According to the department, it has not made a large land acquisition (over 45,000 acres) since the state acquired Anza Borrego State Park in the 1940’s.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget provides $20 million from the General Fund (one time) to acquire property to create a new state park. According to the department, the intent of the proposal is to expand public access to state parks by adding more acreage of park land. (The budget also includes a separate proposal of $4.6 million from three bond funds for smaller park land acquisitions intended to expand existing state parks.)

At the time of this analysis, the specific property, or properties, that the department is considering purchasing have not been identified. The department, however, has developed a list of potential large‑acreage properties it is considering. In addition, the administration hopes other landowners will come forward to express interest in selling their property to the department, which would increase the number of potential sites for a new park.

Assessment

The concept of creating a new state park is consistent with the department’s mission of providing outdoor recreation and protecting natural resources. However, the specific proposal put forward by the department lacks sufficient details, which make it difficult for the Legislature to assess its merits. We identify several key pieces of information that are lacking from the proposal.

Department Will Not Disclose Properties Under Consideration. While the department indicates it has a list of properties it is considering to create a new state park, it indicates that it will not share the list with the Legislature. Not knowing the potential sites for a new park makes it difficult for the Legislature to weigh the merits of the proposal. One key problem is that the Legislature will not be able to determine the extent to which the sites under consideration will effectively increase access to parks, such as by ensuring that sites under consideration are located in areas (1) with relatively few existing parks or (2) near large population centers that would ensure access to a greater number of people. Another issue is that without knowing the properties under consideration, it is unclear whether the $20 million being requested is an appropriate level of funding for acquiring a new state park. Some properties under consideration might cost less than $20 million to purchase, while others may cost considerably more. In addition, it is unclear what type of park the department will acquire, such as a forest, beach, or desert, as well as what other key features the park will have, such as preserving important ecological or historical sites or providing for recreational opportunities.

Proposal Lacks Key Information Needed to Assess Future Costs. Without knowing the details of a specific property, the department indicates it is unable to estimate the costs to build‑out the new park with various infrastructure improvements. Some properties under consideration might already have usable infrastructure, while others may require significant funding to construct or repair basic amenities such as trails, restrooms, roads, parking, or a visitor center. Similarly, Parks has not estimated the ongoing operational costs to support the new park with staff, routine maintenance, and interpretive programs.

Further, the department has not identified the source of funding for these future costs. State parks typically are supported by a combination of General Fund and special funds—particularly the State Parks and Recreation Fund (SPRF), which gets most of its revenues from various park user fees. While a new park, especially if it has a high volume of visitors, could generate significant fee revenue to offset future operating costs, it is likely the new park would require some ongoing General Fund support. (The SPRF currently is being fully utilized to support existing parks and likely does not have a significant enough operating balance to support a new park on an ongoing basis.) Parks indicates that it is exploring options for partnerships with private and nonprofit groups to offset at least a portion of build‑out and operational costs. However, different locations are likely to vary substantially in the opportunities for private or nonprofit funding.

Department Has Not Identified Selection Criteria. While Parks has indicated it is considering multiple properties, the department has not identified the metrics it will use to evaluate these properties and select a preferred site for the new park. The process Parks plans to use to select a property is important, particularly given that it does not intend to provide the Legislature with a list of the properties under consideration. Based on the stated intent for the budget proposal, we might expect one key metric to be an assessment of the extent to which each property would benefit an area that currently has relatively low access to state parks and other outdoor recreation. However, departmental staff has indicated that Parks has not conducted an analysis of park access to identify such “park‑poor” areas. Without an assessment of the biggest gaps in parks access, it is unclear how the department will select a location for the new park that best meets the goal of providing additional park access. In addition, clearly defining selection criteria would help to ensure that the department fully considers other important factors in its decision‑making process, such as future state capital and operating costs, as well as the degree to which each location conserves land that has unique ecological features, historical significance, or is otherwise of statewide interest.

Recommendations

Require Parks to Provide Additional Details. We recommend the Legislature require the department to provide it with the list of potential properties under consideration during the course of spring budget hearings. For each potential property, we also recommend that Parks be required to include estimates of the potential infrastructure build‑out costs, ongoing operational costs, and revenues (from fees or partnerships). In addition, we recommend that the Legislature require Parks to report on the metrics and process it will use to select a site for a new state park.

Determine Action on Proposal Based on Additional Information Provided. If the Legislature receives sufficient information and determines that a new state park is consistent with its short‑term and ongoing budgetary priorities, it may want to approve the proposal. The Legislature also could choose to modify the proposal based on the additional information provided by Parks, such as by providing a different level of funding to align with the range of potential acquisition costs associated with the size and type of park the Legislature would like to see developed.

If the Legislature does not receive sufficient information on the proposal, it may wish to reject the proposal and direct the department to report next year with a more fully developed plan to acquire a new park. While information on the location and type of the new park will be important for the Legislature to weigh the benefits of the proposal, we think that information on the future costs and funding sources to support a new park are particularly critical.

Consider Adopting Reporting Language. To the extent that the Legislature provides funding for a new park in 2020‑21 before a specific site is identified, we recommend that the Legislature approve budget bill language requiring that the department notify the Joint Legislative Budget Committee (JLBC) regarding key details of the acquisition prior to Parks having the authority to spend any of the $20 million. This notice to the JLBC should identify the property the department selected, other properties that were under consideration, the process used to select the property, an estimate of future capital outlay and operational costs, and identification of the funding sources that will be used to fund these future costs.

Increasing Student Access to State Parks

The Governor’s budget includes two proposals to increase student access to state parks. In general, the proposals appear consistent with recent legislative priorities. However, the proposals lack details to fully assess their merits. We recommend the Legislature require Parks to report additional information before taking action on the proposals, as well as consider several oversight questions regarding the broader goals and outcomes of student park access programs.

Background

Increasing Student Access to Parks Has Been a Legislative Priority. Improving student access to state parks has been a priority for the Legislature in recent years. To support this priority, the Legislature has increased funding for park access programs with various funding augmentations from Proposition 68, Proposition 64 (2016), and SPRF. In addition, last year the Legislature passed Chapter 675 of 2019 (AB 209, Limón) to create the Outdoor Environmental Education Grant Program to provide grants to increase access to outdoor environmental education experiences for underserved and at‑risk youth.

Parks Has Several Access Programs. Parks has several programs that increase access to state parks. Two programs that focus specifically on K‑12 students are the Parks Online Resources for Teachers and Students (PORTS) program and the Summer Learning Program (SLP). The PORTS program provides virtual field lessons for students using videoconferencing technology to allow a classroom of students to interact with a park interpreter located at a state park. The department estimates that 74,000 students were served by the PORTS program in 2018‑19. The SLP program coordinates with various nonprofit organizations to host K‑12 students at state parks for day trips and overnight camping trips during the summer. Parks estimates that 4,900 students visited state parks under the SLP program in 2018‑19.

Governor’s Proposals

The Governor’s budget includes two budget proposals that would provide augmentations for programs designed to increase student access to state parks.

- K‑12 Access Program Expansion ($2.9 Million). The budget provides $2.9 million from the Environmental License Plate Fund and 19 positions to expand the PORTS and SLP programs. A portion of the requested positions will replace existing limited‑term or seasonal positions with permanent positions.

- New Outdoor Environmental Education Grant Program ($20 Million). The Governor’s budget includes $20 million (one time) from the General Fund to establish the Outdoor Environmental Education Grant Program created by AB 209.

Assessment

The proposals to expand student access to state parks appear consistent with recent legislative priorities, including the adoption of AB 209. However, the proposals lack basic details necessary to fully assess their merits. For example, the proposal to augment staffing for the PORTS and SLP programs does not identify (1) how many of the requested positions will replace existing limited‑term or seasonal positions and how many will augment the programs, (2) how the new positions would be allocated between the programs, or (3) accurate estimated outcome measures. Without this information, it is not possible to assess what outcomes, such as number of students served by the program, are likely to be achieved. In addition, the department indicates that it has not yet determined how it would allocate grant funds for the Outdoor Environmental Education Grant Program because it has not yet had the opportunity to meet with stakeholders and develop program guidelines. (Assembly Bill 209 directs the department to wait to develop program guidelines until after funding has been appropriated.)

In addition, because the department’s student access programs have generally started as limited efforts—such as pilot efforts or ones facilitated with nonprofit partners—the department has not established broad program goals for the programs or evaluated the most critical gaps in student park access. For example, the department has not created a long‑term goal of the total number of California students that will be served by the various programs or an assessment of the resources necessary to achieve that goal. In addition, the department has not evaluated how it will prioritize student access for over‑subscribed programs.

Recommendations

Obtain Details of PORTS and SLP Proposal Before Taking Action. We recommend that the Legislature require the department to report information on the level of resources currently dedicated to the PORTS and SLP programs, the allocation of proposed new positions between these two programs, and information on how outcome metrics tie to the level of resources budgeted. Regarding the Outdoor Environmental Education Grant Program, the Legislature may want to ask the department about what process it will go through to develop program guidelines if funding is approved.

Consider Broader Oversight Questions. Given multiple recent funding increases provided for park access programs, we recommend the Legislature use these budget proposals as an opportunity to consider broader questions about the goals, administration, marketing, and implementation of the department’s student access efforts. Key oversight questions include:

- Goals. Does the department have long‑term goals for the number of students that it hopes will participate in the PORTS and SLP programs, as well as any other efforts to increase student access? What are the Legislature’s goals for ensuring K‑12 students have access to state parks and outdoor learning experiences?

- Funding. What is it likely to cost to achieve program goals? What are available sources of funding—including potentially nontraditional funding sources for parks—to increase student park access and outdoor learning experiences?

- Prioritization. Given limited funding, what are the most cost‑effective ways of providing student access? Should programs focus on specific grade levels? How should classes and students be prioritized when programs are over‑subscribed? How should the department balance the trade‑offs of virtual park experiences with in‑person park visits? For example, virtual field trips allow more students to participate at lower costs, while in‑person field trips provide a more complete experience and hands‑on learning.

- Communication With Schools. What are the most effective ways of marketing the various programs and sharing information with schools, students, and nonprofit partners? What is the process for receiving feedback from teachers and schools to ensure programs target appropriate grade‑level content and align with curriculum? Are there opportunities for these communication efforts to be streamlined or improved?

Harbors and Watercraft Revolving Fund Insolvency

The Harbors and Watercraft Revolving Fund (HWRF), which is used to support various boating‑related activities, will become insolvent in 2020‑21 absent any intervention. The Governor’s budget includes a “placeholder” solution of $26.5 million to keep the fund solvent, but the specific details of the solution are unclear, as well as whether it would prevent insolvency beyond the budget year if ongoing. We recommend the Legislature consider the following key issues: (1) the structure of the vessel registration fee going forward; (2) the current demand of boating programs and the effects of reduced expenditures from the fund; (3) the extent to which solutions should come from increased revenues, decreased expenditures, and fuel tax revenues; and (4) how to prevent operational shortfalls for the fund on an ongoing basis.

Background

Expenditures for Boating‑Related Activities. The HWRF is used to support various boating‑related activities, including management of invasive aquatic plants and other species and local assistance grants for boating facilities and safety programs. The administration estimates that a total of $79 million will be spent from the fund in the current year, primarily by three departments—Parks, Department of Fish and Wildlife, and the California Department of Food and Agriculture. As shown in Figure 7, $61.7 million is to support various Parks operations, local assistance programs, and capital projects.

Figure 7

Parks Expenditures From the HWRF

(In Millions)

|

Program |

2019‑20 |

|

Aquatic invasive plant removal |

$12.5 |

|

Public safety grants |

11.5 |

|

Launch facility grants |

11.0 |

|

Loan program for boating facilities |

5.5 |

|

Quagga and zebra removal grants |

3.8 |

|

Abandoned watercraft abatement |

2.8 |

|

Capital outlay projects |

2.7 |

|

Oceanography research |

1.5 |

|

Beach erosion control |

1.0 |

|

Other |

9.4 |

|

Total |

$61.7 |

|

HWRF = Harbors and Watercraft Revolving Fund. |

|

Most Revenue Generated From Vessel Registration Fees and Fuel Taxes. The HWRF receives a significant portion of its revenue from vessel registration and renewal fees, as well as a transfer from Motor Vehicle Fuel Account (MVFA).

- Vessel Registration and Renewal Fees. Vessel registration in the state is conducted on a biennial basis. The state charges an initial registration fee of $65 for most vessels ($37 in even years, the second year of the two year cycle). A majority of the fee is deposited into the HWRF, while a small portion is deposited into the Air Quality Improvement Fund and the Alternative and Renewable Fuel and Vehicle Technology Fund. The state also charges a registration renewal fee that is due every two years on odd numbered years. The fee is $36 for most vessels. The full amount of the renewal fee is deposited into the HWRF. As a result of the renewal fee being collected on a biennial basis, fee revenue fluctuates predictably each year. The HWRF generally receives about $4 million in even years and $27 million in odd years. Both the initial registration and renewal fees include a base fee and a supplemental fee for activities to prevent the spread of the quagga mussel, an invasive species.

- Transfer From MVFA. The HWRF also receives an annual transfer from the MVFA. The transfer reflects the estimated amount of state fuel taxes paid by vessel owners. The amount transferred is based on the number of registered boats in the state and has ranged from $18 million to $29 million annually in recent years.

Operational Shortfall and Insolvency. Over the last several years, the HWRF has periodically faced operational shortfalls—meaning planned expenditures have exceeded combined revenues and transfers. Operational shortfalls have typically occurred in even years when the registration renewal fee is not due. However, prior‑year reserves have been able to support the fund during these periods.

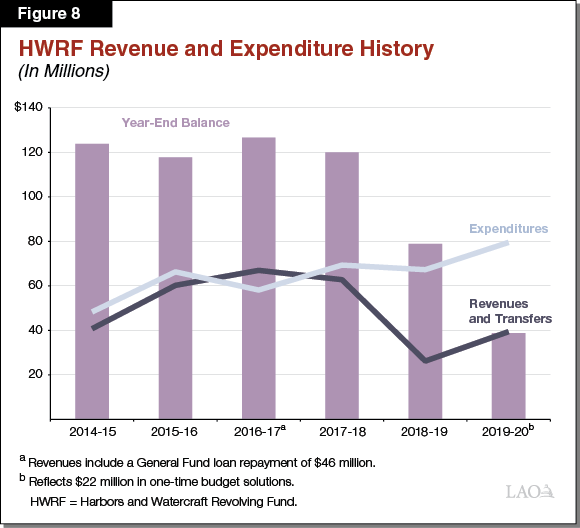

The operational shortfalls were exacerbated because of a technical correction that was made as part of the 2019‑20 budget. The change was intended to better reflect past legislative intent related to how fuel tax revenues associated with vessels is distributed among the HWRF, SPRF, and the General Fund. The outcome of the change, however, is a significant decrease in the amount of MVFA funds transferred to the HWRF. For instance, the MVFA transfer fell from $23 million in 2018‑19 to $8 million in 2019‑20. The 2019‑20 budget also included a one‑time solution of $22 million—from a combination of a reversion of unencumbered local assistance appropriations and a transfer from the Public Beach Restoration Fund—to offset the reduced transfer. The fund is still estimated to have an operational shortfall of $40 million at the end of the current year, which will result in estimated reserves of $38.8 million. Figure 8 shows historical revenues and expenditures from the HWRF.

Governor’s Budget

Absent any corrective actions, the administration estimates that the HWRF will experience an operational shortfall of $64 million in the budget year. This would cause the fund to fully deplete its remaining reserves and become insolvent. In recognition of this problem, the Governor’s budget includes a placeholder solution of $26.5 million to keep the HWRF from becoming insolvent. The budget assumes half of this amount would come from increased revenue and half from expenditure reductions. However, at the time of publication, the administration had not identified what specific actions it would propose and, instead, states that it intends to have a more complete proposal later this spring.

Assessment

Unclear Whether Placeholder Solution Would Prevent Insolvency Beyond Budget Year. While the Governor’s budget includes a $26.5 million placeholder solution, the lack of specificity provided makes it difficult to evaluate whether the solution would prevent the HWRF from becoming insolvent in subsequent years. While the current level of funding assumed in the placeholder solution would allow for the fund to remain solvent in the budget year, it would also force the fund to deplete its remaining reserves to $1.3 million. Assuming the $26.5 million solution is ongoing, we estimate that there would continue to be an operational shortfall in 2021‑22 of about $28 million. This would ultimately place the HWRF in a similar situation to what it is currently experiencing. Accordingly, it is in the interest of the Legislature to approve a solution that would keep the fund solvent in future years.

Options for Addressing the Operational Shortfall. While the Governor does not yet have a specific proposal, there are a wide range of options for the Legislature to consider. Accordingly, it will be important for the Legislature to establish its priorities for the HWRF and determine how best to address the projected insolvency in 2020‑21. While the Governor’s placeholder solution could help the fund remain solvent in the budget year, it is unclear whether it would address the operational shortfalls beyond 2020‑21. Accordingly, the Legislature will want to consider long‑term solutions in addressing the structural imbalance. In order to assist the Legislature in developing its plan, we identify a framework of options for its consideration:

- Increase Revenues. The Legislature could generate additional revenues by increasing vessel registration or renewal fees. Roughly, a $1 increase in the renewal fee, for instance, would generate about $750,000 in odd years. We also note that the base registration renewal fee was last updated in 2005. As time has progressed, the fee has lost its relative purchasing power due to inflation. This may provide a rationale for the Legislature to increase the fee to reflect its current year value, which would result in about a $7 increase in the fee. The Legislature could also consider indexing the registration and renewal fees to inflation, which would align them with similar registration fees placed on motor vehicles.

- Reduce Expenditures From HWRF. The Legislature could also reduce expenditures by decreasing the amount allocated to specific programs supported by the fund. As noted earlier, overall expenditures from HWRF have increased significantly in recent years from $48 million in 2014‑15 to $79 million in 2019‑20. A reduction in expenditures also may be warranted given the decrease in fuel tax revenue transferred from the MVFA to the HWRF going forward, though the Legislature would want to consider the impact to programs of any reduction in expenditures.

- Shift More MVFA Funds to HWRF. As mentioned earlier, some of the fuel tax revenue related to vessels is transferred to the General Fund and the SPRF. This is a result of vessel fuel tax revenue not being limited for only transportation purposes under the California Constitution—in contrast to fuel tax revenue collected from motor vehicles. The Legislature could eliminate or reduce the amount transferred into these funds in order to support the HWRF. For instance, the MVFA is expected to transfer $35 million of fuel tax revenue related to vessels to the General Fund in the budget year. To the extent that a portion of these funds was shifted from the General Fund to HWRF, this would reduce funding available for the Legislature’s General Fund priorities.

Recommendation

Consider Key Issues in Budget Deliberations. The Governor’s budget plan currently lacks a detailed proposal. However, even in the absence of a proposal, we recommend the Legislature consider key issues when weighing different options for addressing the insolvency in 2020‑21 and the longer‑term operational shortfall in the HWRF. This could include directing the administration to report additional information on the following topics at budget hearings:

- Structure of the Registration Fee. How do California’s vessel registration fees compare to other states? Would it make sense to have a range of registration and renewal fees that are based on the size of a vessel? What are the trade‑offs between a flat fee versus a tiered fee?

- Effects on Reducing Expenditures. What is the current demand for boating‑related programs—such as facilities, safety, and invasive aquatic plant and species removal? How would a reduction in expenditures from the HWRF affect state goals for each of these programs?

- How to Balance Different Options. How does the administration intend to reach the $26.5 million adjustment for the HWRF? To what extent should budget‑year or longer‑term solutions come from increased revenues, decreased expenditures, and fuel tax revenues?

- Future Health of HWRF. How does the administration intend on preventing operational shortfalls on an ongoing basis for the HWRF? How will the proposed solution ensure that the fund is supported during even years when the renewal fee is not being collected? What level of ongoing solutions would be needed to ensure that the fund builds reserves going forward?

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) is responsible for promoting and regulating the hunting of game species, promoting and regulating recreational and commercial fishing, and protecting California’s fish and wildlife for the public trust. The department manages over 1 million acres of public land throughout the state including ecological reserves, wildlife management areas, and hatcheries.

The 2020‑21 Governor’s Budget proposes total expenditures of $573 million for CDFW from various sources, an increase of $13 million (2 percent) compared to current‑year expenditures. This increase reflects the net total of the proposed augmentations described in the next section and the removal of several one‑time, current‑year appropriations. Of the total proposed expenditures, $172 million comes from the General Fund (30 percent), $115 million from the Fish and Game Preservation Fund (FGPF, 20 percent), $86 million from federal funds (15 percent), $46 million from general obligation bond funds (8 percent), and the rest from other special funds.

Funding Enhancements

The Governor proposes $19 million ongoing and $20 million one time in 2020‑21 to help CDFW better meet its mission, primarily for activities to protect fish and wildlife. While we find that the proposed activities have merit, funding for the ongoing activities would be shifted from other state conservation programs. We recommend the Legislature adopt the one‑time funding proposal and weigh the relative trade‑offs of the ongoing proposal with its other conservation and General Fund priorities. We recommend deferring action on a third component of the Governor’s proposal—to extend funding scheduled to expire in 2021‑22—until next year when a more in‑depth analysis of CDFW’s budget will be available.

Background

CDFW Has Experienced a Roughly $20 Million Ongoing Budget Shortfall. As noted, the FGPF is among the department’s largest funding sources, providing roughly one‑fifth of overall CDFW resources. The fund receives revenues from a variety of fees, including recreational hunting and fishing license and permit fees. Expenditures from the FGPF support many of the department’s core activities, including various wildlife conservation efforts, law enforcement, management of both department‑owned lands as well as inland and coastal fisheries, and oversight over the state’s commercial fishing industries. In recent years, expenditures from the FGPF have exceeded its revenues by roughly $20 million annually. This gap developed in large part because the state has created new costs for the fund without adding an equivalent amount of new revenues. These costs have resulted from significant employee salary increases negotiated through the state collective bargaining process, assigning new activities to CDFW without providing new funding, and shifting activities from other funding sources to the FGPF.

2018‑19 Budget Provided Funding for Three Years to Address Shortfall and Expand Programs. In 2018‑19, the Legislature augmented CDFW’s budget by roughly $30 million, with about $23 million of this amount expiring in 2021‑22. The total augmentation consists of:

- $20 million in additional General Fund for the department to address its funding shortfall and maintain its existing service levels—roughly $7 million ongoing and about $13 million for three years.

- $10 million annually for three years—one‑half from the General Fund and one‑half from the Tire Recycling Management Fund—along with 30 new positions for CDFW to expand its activities. Figure 9 summarizes how the department has used that funding augmentation.

Figure 9

Recent CDFW Service Expansions

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Activity |

Funding |

Positions |

|

Law enforcement/wildlife trafficking prevention |

$3.7 |

6 |

|

Marine fisheries management |

2.7 |

11 |

|

Salmon monitoring and conservation support |

1.3 |

4 |

|

Hatchery production support |

1.0 |

1 |

|

Status reviews of endangered species |

0.6 |

2 |

|

Administrative support |

0.4 |

3 |

|

Collaborative conservation activities |

0.3 |

3 |

|

Totals |

$10.0 |

30 |

|

CDFW = California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

||

Legislature Directed CDFW to Undertake a Detailed Review of Its Activities and Budget. Along with funding increases, the 2018‑19 budget package included a requirement that CDFW conduct a service‑based budget (SBB) review by January 2021. This review is intended to provide more clarity regarding the following:

- The core activities that CDFW undertakes.

- The existing gap between the department’s “mission” level of service (defined as the service standards and essential activities required for the department to meet its mission and statutory requirements) and its current service levels.

- Instances where CDFW may be conducting activities outside its mission and statutory requirements.

- Detailed estimates for the costs and staffing that would be necessary to meet mission service levels.

- An analysis of the department’s existing revenue structure and the activities supported by those fund sources, including instances where different funding sources or revenue structures might be allowable or more appropriate.

The budget package also required that the SBB review include development of a new budget tracking system to inform ongoing and future fiscal decision‑making processes.

The Legislature has provided $4 million in one‑time General Fund to support these activities. CDFW is still in the middle of the SBB process. Specifically, it has accomplished two of the tasks described—defining current and mission service levels and their relative gap in terms of staffing levels—but has not yet determined what it would cost to fully achieve its mission or analyzed its revenue sources and comparative distribution of funding.

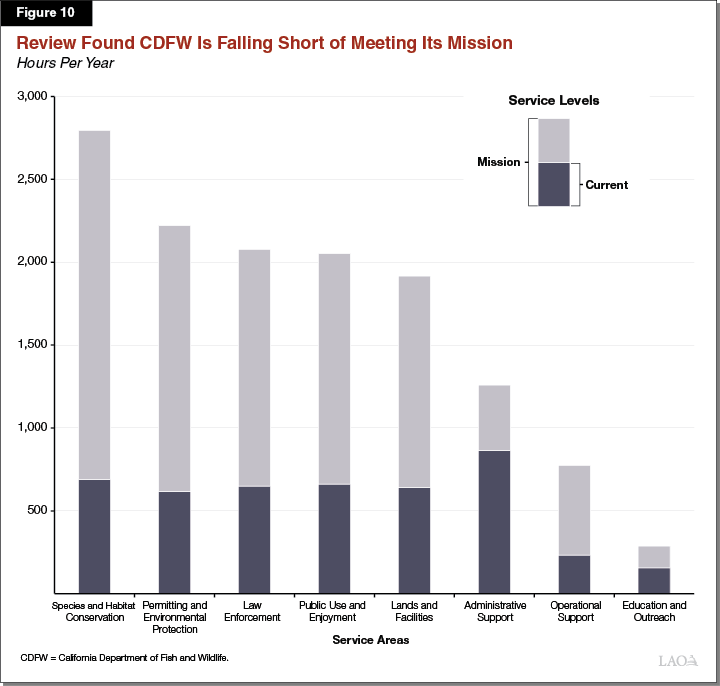

SBB Review Determined Existing Service Levels Fall Short of Meeting Mission. While CDFW has not yet completed the SBB review, its initial analysis has identified significant gaps between its existing levels of service and those it has determined would be necessary to fulfill its mission and meet all of its statutory responsibilities. Figure 10 displays these results, showing the difference between the number of staff hours currently being dedicated in each of CDFW’s eight areas of service compared to the number of hours the department has determined would be needed to meet its mission. As shown, in most areas, CDFW has determined that current service levels are less than one‑third of mission levels. The largest shortfall—both proportionally and in terms of total staff hours—is in species and habitat conservation, the service area the department has determined requires the most comparative workload. Specifically, CDFW staff currently spend about 690,000 hours per year on activities in that service area, compared to the 2.8 million hours the department estimates would be needed to meet its mission. The second largest gap is in the permitting and environmental protection service area—falling short of meeting mission service levels by about 1.6 million hours annually.

CDFW Reviewing Both Staffing and Other Options to Address Shortfalls. Notably, while the initial SBB review focused on identifying shortfalls in service levels defined solely by staffing hours, CDFW indicates that the next phase of its analysis will identify strategies for narrowing those gaps through various approaches—not just by seeking to add staffing resources and labor hours. For example, the department plans to investigate whether it could (1) adjust mission level expectations by making legislative, regulatory, or policy changes; (2) increase efficiencies within the department to lessen the number of staff hours needed to meet mission service levels, such as by streamlining processes or acquiring new technology or equipment; and (3) collaborate with partner agencies to help complete some tasks.

Legislature Recently Reauthorized Funding for Wildlife Conservation Programs. The Habitat Conservation Fund (HCF) provides $30 million annually for wildlife conservation efforts. These monies have been used primarily for grants to purchase land to preserve as undeveloped wildlife habitat, as well as to fund habitat restoration projects. Statute prescribes particular categories of uses at certain departments for these funds. For example, $10 million per year must be spent to protect deer and mountain lion populations, with a particular emphasis on native oak forests. Additionally, at least $3 million annually must be spent to acquire and restore stream and riparian habitat, and another $3 million to acquire and restore wetlands.

Of the total $30 million provided annually, statute requires the following allocations: (1) $4.5 million to Parks, (2) $4 million to the State Coastal Conservancy, (3) $500,000 to the Tahoe Conservancy, and (4) the remainder (which totals $21 million) to the Wildlife Conservation Board (WCB). Revenues into the HCF consist of about $11 million annually from statewide tobacco taxes and roughly $19 million from the General Fund and are continuously appropriated to the specified departments. The HCF—along with requirements for its annual revenues and specified categories of uses—was originally established in 1990 by a voter‑approved initiative, Proposition 117. The requirements are scheduled to expire at the end of 2019‑20. As part of the 2019‑20 budget package, however, the Legislature adopted budget trailer legislation extending the requirement that the state ensure a total of $30 million be continuously appropriated into the HCF to continue the existing categories of uses by WCB and the other departments until 2030.

Governor’s Proposals

The Governor proposes three separate augmentations from the General Fund for CDFW. Figure 11 summarizes the two proposals for 2020‑21. The third proposal would not take effect until 2021‑22. Next, we describe each of the three proposals.

Figure 11

Summary of Governor’s 2020‑21 CDFW Funding Proposals

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Activity |

Description |

Funding |

Positions |

|

New Ongoing Proposals |

|||

|

Protect endangered species |

Conduct work to implement and enforce compliance with CESA, including reviewing petitions to list new species as threatened or endangered, processing and monitoring CESA‑related regulatory permits, and developing and implementing plans to help CESA‑listed species recover. |

$10.8 |

31 |

|

Increase awareness about biodiversity and climate change |

Conduct climate‑risk assessments on CDFW lands. Develop and disseminate education and outreach materials about state’s biodiversity and climate change risks. |

1.9 |

7 |

|

Improve permitting process for restoration projects |

Direct additional staff resources to consult with restoration project proponents and process environmental permits to expedite time lines and enable permitting for larger scale projects. |

3.4 |

15 |

|

Administration and facilities |

Provide administrative support and office space proportional to new staff and activities included in overall proposal. |

2.8 |

5 |

|

Totals |

$18.9 |

58 |

|

|

New One‑Time Proposals |

|||

|

New aircraft |

Purchase new aircraft to aerially monitor wildlife. |

$6.0 |

— |

|

Fish hatchery equipment |

Purchase equipment to upgrade hatchery operations, including egg sorters and fish stocking vehicles. |

6.5 |

— |

|

Equipment and water conveyance projects at state wetlands |

Undertake projects to improve water conveyance, including upgrading canals, levees, and water pumps, and installing solar‑panels. Purchase new heavy equipment for maintenance including tractors, graders, and excavators. |

7.5 |

— |

|

Total |

$20.0 |

||

|

CDFW = California Department of Fish and Wildlife and CESA = California Endangered Species Act. |

|||

$18.9 Million Ongoing Redirected From WCB’s HCF Programs to Expand Species Conservation Activities at CDFW. The Governor proposes $18.9 million in new ongoing funding to be used primarily to augment CDFW’s habitat and conservation activities. This includes increasing compliance with the California Endangered Species Act (CESA) and a pilot approach to expediting regulatory permitting processes for restoration projects (as described in more detail in the nearby box). While the proposed $18.9 million augmentation would provide new resources for CDFW, these funds would not represent new General Fund spending for the state. Rather, the Governor proposes to shift these funds from their existing uses within the HCF. (To implement this shift the Governor proposes budget trailer legislation to undo the recent statutory reauthorization of funding for the HCF.) As described earlier, WCB and other departments currently use these funds—together with funding from voter‑approved bonds—primarily to acquire and preserve land for conservation. Because of existing statute specifying the amounts that must be provided to Parks, the State Coastal Conservancy, and the Tahoe Conservancy, the funding shift would come from WCB’s portion of the HCF—leaving WCB with only about $2 million of its existing $21 million in HCF funds. The Governor’s proposal does not include backfilling these funds for WCB.

Proposal Includes Pilot Initiative to Expedite Restoration Projects

As noted in Figure 11, included within the Governor’s proposal is $3.4 million and 15 new positions to improve the permitting process for habitat restoration projects. This is part of a larger initiative being championed by the Secretary for Natural Resources to “Cut the Green Tape” and make getting regulatory approvals for undertaking restoration projects easier, quicker, and less costly. This effort is in response to feedback from proponents of restoration projects that the prolonged process for attaining necessary permits is onerous, duplicative, and inhibits them from implementing large scale projects. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s particular proposal would pilot a new approach in one selected region of the state to help expedite time lines for granting environmental permits. Specifically, the requested funding would support a “strike team” of staff working on grant administration and permitting to provide early consultation with project proponents, hold permitting workshops, and seek to incorporate the use of existing “programmatic” permitting options that could facilitate larger scale restoration projects. To start, this pilot effort would be focused on the North Coast region of the state (Humboldt, Mendocino, Del Norte, Sonoma, and Marin Counties).

$20 Million One Time From General Fund to Upgrade Equipment and Operations. The Governor proposes one‑time funding to be used primarily to purchase equipment and undertake projects that would improve efficiency throughout the department’s operations. This includes replacing one outdated aircraft and purchasing 43 fish stocking vehicles, 18 hatchery egg‑sorting machines, and 18 units of heavy equipment for maintaining state wetlands. The funding would also support 15 projects at state wetlands to improve both energy and water‑use efficiency. This includes upgrading pumps and canals and installing solar arrays to power water conveyance.

$23.4 Million Ongoing General Fund Beginning in 2021‑22 to Backfill Shortfall and Maintain Service Expansions. The Governor proposes that the Legislature act now to authorize funding for 2021‑22 that would allow the department to sustain existing service levels—including the recent expansions described in Figure 9—when the three years of funding provided by the Legislature in 2018‑19 is scheduled to expire.

Assessment

Ongoing Funding Addresses Some Service Gaps, but Legislature Could Prioritize Other Activities. As described previously, CDFW has identified a significant deficit in existing service levels, with the largest gaps in the areas of (1) species and habitat conservation and (2) permitting and environmental protection. Most of the Governor’s proposals for new ongoing funding are targeted in these categories, suggesting they would help the department be better positioned to carry out its mission. As such, we find that the proposed use of the new $18.9 million seems well‑targeted for addressing existing deficiencies in CDFW’s services. For example, as shown in Figure 11, the proposal includes $10.8 million for activities that would help the department increase statewide compliance with CESA. The SBB review found that CDFW staff time currently is only sufficient to address 23 percent of its mission service levels related to issuing and enforcing CESA permits, and 38 percent of mission‑level workload to manage and monitor endangered species. This means that the department is not able to consistently research and monitor the status of species that have been designated as endangered or are most at risk of being threatened with extinction. Similarly, the proposed $3.4 million to expedite restoration projects could help address the roughly 450,000 hours per year SBB‑identified gap between current and mission service levels in the department’s programs to restore and enhance wildlife habitats. This deficit means that existing CDFW staff often do not have time to consult with stakeholders who seek to undertake restoration projects to ensure their proposals are effectively designed, focus on state wildlife priorities, and meet regulatory requirements.