LAO Contacts

- Ross Brown

- Cap-and-Trade Expenditure Plan

- Rachel Ehlers

- Climate Adaptation Research and Technical Assistance

- Climate Bond

- Brian Weatherford

- Climate Catalyst Loan Fund

February 13, 2020

The 2020‑21 Budget:

Climate Change Proposals

- Introduction

- Overview of Governor’s Proposals

- Key Issues to Consider

- Cap‑and‑Trade Expenditure Plan

- Climate Research and Technical Assistance Funding

- Climate Catalyst Revolving Loan Fund

- Climate Bond

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

In this report, we assess the Governor’s major 2020‑21 budget proposals related to climate change. The four proposals we evaluate are:

- Cap‑and‑Trade Expenditure Plan ($965 Million). The budget includes a $965 million (Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund [GGRF]) discretionary cap‑and‑trade expenditure plan. Funding would mostly go to a variety of existing environmental programs, including programs related to low carbon transportation, local air quality improvements, and forestry.

- Expanded Climate Adaptation Research and Technical Assistance ($25 Million). As part of the cap‑and‑trade expenditure plan, the Governor proposes $25 million (GGRF) ongoing for several new and expanded climate adaptation research and technical assistance activities.

- New Climate Catalyst Loan Fund ($250 Million). The budget proposes $250 million (General Fund) in 2020‑21 and an additional $750 million in 2023‑24 to establish a new Climate Catalyst Revolving Loan Fund (Climate Catalyst loan fund). The fund would lend money to public and private entities for climate‑related projects that have difficulty getting private financing.

- Climate Bond ($4.8 Billion). The Governor proposes a $4.75 billion general obligation bond for the November 2020 ballot that would fund various projects intended to reduce the impacts of climate change. Approximately 80 percent of the funds would address near‑term risks—such as floods, drought, and wildfires—with the remainder to address the longer‑term risks of sea level rise and extreme heat.

Key Issues to Consider. There are a variety of important considerations that the Legislature will want to weigh as it constructs a climate change package. Notably, the Governor proposes a significant increase in the amount of General Fund resources allocated to climate‑related activities, including significant out‑year commitments to pay off the proposed bond. We urge the Legislature to think broadly about its priorities and the role of the General Fund, GGRF, and other funds—as well as nonfinancial tools, such as regulatory programs—in achieving its climate goals. Key considerations when developing an overall approach include:

- Is the overall spending amount consistent with legislative priorities, considering the potential need and the wide variety of other potential uses of the funds?

- How does the Legislature want to prioritize funding for adaptation versus mitigation? As part of that evaluation, the Legislature might want to consider the existing levels of spending for each type of activity, as well as the relative merits of relying on funding to achieve these goals versus other strategies, such as regulations.

- How should funds be allocated in order to most effectively achieve the Legislature’s climate goals? Programs that receive funding should (1) have clearly defined goals and objectives, (2) be well coordinated across different government entities, (3) address clear market failures and complement regulatory programs, and (4) have effective strategies and resources for evaluating future outcomes.

Cap‑and‑Trade. Proposed discretionary spending is about $250 million less than in the current year and would largely go to programs that the Legislature has already committed to funding on a multiyear basis or that have received one‑time funding in past budgets. Significant adjustments from last year’s budget include expanding various climate adaptation research and technical assistance activities and reducing funding for the Clean Vehicle Rebate Project. Overall, we find that the size of the proposed expenditure plan is reasonable given the available resources, though resources available in future years might be even lower. We also find that the rationale and methods used by the administration to prioritize limited funding, as well as the expected outcomes, are unclear. Based on these findings, we recommend the Legislature (1) ensure multiyear discretionary expenditures do not exceed $800 million, (2) direct the administration to provide additional information on expected outcomes, (3) allocate funds according to legislative priorities, and (4) consider other funding sources for high‑priority programs.

Climate Adaptation Research and Technical Assistance. Providing an additional $25 million in ongoing funding for climate adaptation research and technical assistance activities would be a significant increase compared to existing funding and state‑level efforts. We find that the types of activities the Governor includes in his proposals—conducting and disseminating research, clarifying statewide priorities and setting measurable objectives, and assisting vulnerable and under‑resourced communities—are worthwhile areas on which to focus state‑level efforts. Yet, while the Governor’s proposal represents one approach to answering these questions, an alternative package with a somewhat different design could also be reasonable. We recommend the Legislature increase state‑level efforts related to climate adaptation with a package that (1) includes the climate adaptation research and technical assistance activities it views to be the highest priorities, (2) provides funding sufficient to support those activities, and (3) assigns the activities to the state‑level entities it believes are best suited to manage their implementation. We also recommend the Legislature adopt statutory language for any high‑priority climate adaptation activities over which it wants to provide guidance to ensure greater accountability.

Climate Catalyst Loan Fund. There are likely some appropriate climate projects that could benefit from a state‑administered revolving loan program—specially, those that (1) provide climate benefits, (2) are low financial risk, and (3) would otherwise be unable to attract conventional financing. However, we find that the administration has not adequately justified the proposal, particularly because the administration has not demonstrated that it will be able to identify such projects, especially at the scale of $1 billion. Furthermore, these funds could be used for other legislative priorities, and existing state programs support many of the same projects that the administration has indicated might be funded through the Climate Catalyst loan fund. We recommend the Legislature reject the proposal. Given the potential merit of a loan program, the Legislature could consider funding a smaller scale pilot program. This would allow the administration to define which projects would be eligible, demonstrate its ability to identify appropriate projects, and establish the actual demand for such loans prior to setting aside a significant amount of money.

Climate Bond, The Governor’s proposal lays out one approach to designing a climate bond, but the Legislature has other options. As the Legislature deliberates whether to pursue a climate bond at either the Governor’s proposed level or for a different amount, we recommend it consider the out‑year implications for the state budget. We also recommend it focus on the categories of activities it thinks are the highest priorities for the state, including how much to spend responding to more immediate climate effects as compared to preparing for impacts that have a longer time horizon. Additionally, we recommend the Legislature adopt bond language to ensure dollars are used strategically to maximize their impact at addressing climate change risks, as well as include evaluation criteria to ensure the state will measure and learn from project outcomes.

Introduction

Climate Change Impacts and Recent Actions. Researchers project that climate change will have myriad consequential effects throughout California. These include sea‑level rise, inland flooding, more severe heat days, more frequent drought, and increased risk of wildfires. These climate change effects have the potential to damage infrastructure, adversely affect human health, impair natural habitats, and affect regional economies.

State and local governments are already taking action to try to reduce the magnitude of future damages from climate change. Perhaps most notably, the Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006 (Chapter 488 [AB 32, Núñez/Pavley]) established the goal of limiting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions statewide to 1990 levels by 2020. Subsequently, Chapter 249 of 2016 (SB 32, Pavley) established an additional GHG target of reducing emissions by at least 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030. To achieve these goals, the state has adopted a wide variety of regulations and provided funding to different programs—largely from the state’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF)—to reduce emissions. Collectively, these activities are often referred to as climate mitigation.

Another set of actions—often known as climate adaptation—relates to planning for and implementing projects that reduce the risk of future damages that could occur as a result of climate change even if global GHG emissions are reduced substantially in the coming decades. Unlike mitigation, there are no statutory statewide goals guiding climate adaptation, but the state is in the early stages of expanding and increasing its focus on adaptation activities.

Structure of This Report. This report provides our review of the Governor’s major 2020‑21 budget proposals related to climate change and is structured in six parts. First, we provide a brief overview of the Governor’s “climate budget.” Second, we identify key issues for the Legislature to consider to help guide its evaluation of the merits of each proposal. Lastly, we discuss each of the Governor’s four major proposals—(1) the cap‑and‑trade expenditure plan, (2) expanded funding for climate‑related research and technical assistance, (3) establishment of the Climate Catalyst Revolving Loan Fund, and (4) a $4.8 billion bond—in detail, including a description, our assessment, and associated recommendations.

Overview of Governor’s Proposals

The Governor’s budget for 2020‑21 includes a wide variety of proposals related to climate change mitigation and adaptation. In this report, we focus on four major proposals:

- Cap‑and‑Trade Expenditure Plan ($965 Million). The budget includes a $965 million (GGRF) discretionary cap‑and‑trade expenditure plan. (Total cap‑and‑trade expenditures in 2020‑21 are projected to be $2.7 billion, including continuous appropriations and other existing statutory allocations.) Discretionary spending is about $250 million less than in the current‑year budget due to lower available resources. Funding would mostly go to a wide variety of existing environmental programs, including programs related to low carbon transportation, local air quality improvements, and forestry.

- Expanded Climate Adaptation Research and Technical Assistance ($25 Million). As part of the cap‑and‑trade expenditure plan, the Governor proposes $25 million (GGRF) ongoing for a variety of new and expanded climate adaptation research and technical assistance activities. These activities would be administered by the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research (OPR), the Strategic Growth Council (SGC), the California Natural Resources Agency (CNRA), and the California Energy Commission (CEC).

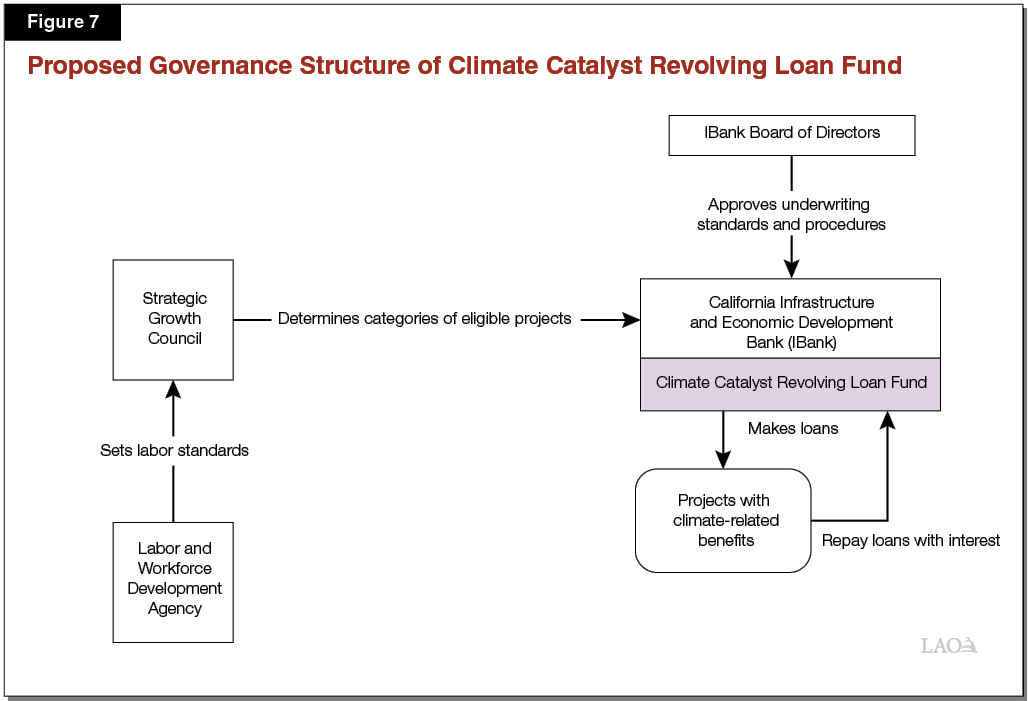

- New Climate Catalyst Loan Fund ($250 Million). The budget proposes $250 million (General Fund) in 2020‑21 and an additional $750 million in 2023‑24 to establish a new Climate Catalyst Revolving Loan Fund (Climate Catalyst loan fund). The fund would make low‑interest loans to public and private entities for climate‑related projects that have difficulty getting private financing. The Climate Catalyst loan fund would be administered by the California Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank (IBank) in consultation with SGC and the Labor and Workforce Development Agency.

- Climate Bond ($4.8 Billion). The Governor proposes a $4.75 billion general obligation bond for the November 2020 ballot that would fund various projects intended to reduce future climate risks. Approximately 80 percent of the funds would be allocated to address near‑term risks, such as floods, drought, and wildfires. The remaining 20 percent would address longer‑term climate risks of sea level rise and extreme heat.

Key Issues to Consider

The Governor proposes funding for a wide range of climate‑related activities—some of which would fund existing programs, while some would go to new programs. Given the size and complexity of the major climate‑related proposals—as well as the interaction between the different proposals—we identify several high‑level issues for the Legislature to consider as it evaluates each of the Governor’s major climate change proposals. These key issues are summarized in Figure 1 and discussed in more detail below.

Figure 1

Key Issues to Consider When Evaluating Climate Budget Proposals

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Allocating Funding Based on Legislative Goals and Priorities. We suggest the Legislature think broadly when considering funding for climate change activities—beyond the specific climate‑related proposals from the Governor. Notably, unlike prior years, the Governor proposes a significant amount of new General Fund resources for climate‑related activities. The Legislature could increase or decrease this overall amount, depending on its priorities. Given the potential magnitude of the future impacts of climate change, it could consider allocating additional funding to help reduce those future impacts. On the other hand, spending more for climate activities means less money for other legislative priorities. For example, the Governor proposes an additional General Fund allocation of $750 million to the new Climate Catalyst loan fund in 2023‑24. This allocation would occur in the same year the Governor proposes to suspend recent health and human services program augmentations if the state does not collect sufficient General Fund revenue. The Legislature will want to consider whether this overall approach is consistent with its priorities.

Furthermore, the Legislature could adjust budget allocations between different climate‑related programs depending on the relative weight given to adaptation, GHG mitigation, and other environmental goals. For example, given the wide variety of existing regulatory programs in place intended to reduce GHG emissions and the limited funding that has historically been used for adaptation activities, the Legislature could prioritize more funding for adaptation activities.

Additionally, once it determines the amount of funding for either adaptation or mitigation, the Legislature will want to consider how it prioritizes across potential areas of focus. For example, it has a choice between how much emphasis to place on—and funding to dedicate for—addressing the climate impacts the state has already begun experiencing (like more severe wildfires and droughts) as compared to longer‑term challenges (like sea‑level rise). Furthermore, the Legislature could increase funding for activities such as research and technical assistance to help guide climate mitigation and adaptation activities, but will want to balance those priorities along with providing funding directly to implement projects. The Legislature could also consider how much funding it wants to dedicate to addressing risks to state assets and programs compared to risks to local communities.

Selecting Programs That Are Likely to Achieve Goals Effectively. After the Legislature establishes its goals and priorities for the use of state funds, it will want to consider which programs achieve these goals most effectively. First, when considering how mitigation funding can be allocated most effectively to reduce GHGs, we recommend the Legislature consider the following issues:

- Coordination and Interactions With Other Programs. The state has dozens of different programs aimed at reducing GHG emissions—many of which are regulatory programs. Figure 2 summarizes some of the key policies and programs in different sectors. Many of the mitigation activities that would be funded in the budget target the same source of emissions. We recommend the Legislature consider how the proposed new programs would interact with the existing programs, including regulatory programs. This could include assessing whether the state needs multiple programs targeted at the same sources of emissions, how well the multiple programs would be coordinated, and the degree to which the proposed funding program actually would reduce emissions versus simply reduce the costs of complying with one or more of the regulatory programs.

- Identifying Market Failures. When considering how to target programs effectively, the Legislature might want to consider whether private entities currently lack appropriate incentives and adequate information to undertake cost‑effective GHG reduction activities (also known as market failures). For example, when private firms invest in research and development activities for new technologies, they often do not capture all of the benefits from those investments. This is because other firms—and consumers—are often able to benefit from the new knowledge and innovation that is created. This is sometimes referred to as “knowledge spillovers.” Knowledge spillovers serve as a key rationale for government programs that provide grants or subsidies for research and development of new technologies. An assessment of this issue might include whether new program proposals—such as the Climate Catalyst loan fund—address a clear market failure and if there is a clear explanation of how the proposed program would be the most effective strategy for addressing the problem.

- Impact on Emission Reduction Activities in Other Jurisdictions. California emits roughly 1 percent of global GHGs. As a result, perhaps the most significant effect of California’s climate policies will be how they influence GHG emission reduction activities in other jurisdictions. For example, demonstrating to other countries how to design and implement cost‑effective policies to reduce GHGs could make them more likely to implement such policies. In addition, policies that encourage innovation and low‑GHG technologies could make such technologies less expensive to implement in other parts of the country or world. As a result, this could increase the likelihood of these technologies being adopted in other jurisdictions. The value of these GHG reductions could far exceed those that occur strictly within California. Therefore, when reviewing various climate proposals, the Legislature might want to consider how the state can best design its climate policies in a way that is most likely to encourage GHG reductions in other jurisdictions.

Figure 2

Major Policies to Meet Statewide Greenhouse Gas Limits

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Second, when considering which adaptation programs are likely to be the most effective use of state resources, we recommend the Legislature consider the following:

- Key Climate Resilience Objectives. Unlike with mitigation, the state has not yet established specific statutory goals to guide its climate adaptation efforts. As such, policymakers should carefully consider the key outcomes they hope to achieve from investments in climate adaptation projects, and whether proposals would contribute toward meeting those objectives. In considering the merits of adaptation proposals, the state may want to start by focusing on issues that have the most statewide interest, such as activities that would meaningfully reduce the risk of damage from climate change to state‑owned infrastructure and public trust natural resources, as well as those that would help protect public health and safety.

- Strategic Coordination Across Efforts. To effectively respond to the challenges posed by climate change, the state should employ an organized and deliberate strategy. Individual adaptation projects that are geographically isolated or undertaken without a larger plan will have limited effectiveness at reducing risk and could be easily counteracted if conflicting land‑use decisions are implemented nearby. Therefore, we recommend the Legislature consider whether proposed adaptation programs and projects are part of a regional coordinated approach towards reducing climate risk.

Identifying Appropriate Entities to Administer Programs. For all programs—and especially new ones—we suggest the Legislature consider the entity that is most appropriate to administer the program. Such a decision should be based, in large part, on whether the entity has the appropriate expertise and capacity to administer the program. For example, when evaluating the proposal for the new Climate Catalyst loan fund, the Legislature will want to consider whether IBank has adequate expertise to identify appropriate private projects and assess their risks.

Also, the Legislature will want to consider whether related activities occurring in many different departments are likely to be well coordinated. For example, the proposed climate adaptation research activities would be conducted in several different departments and agencies. It is worth considering whether there is a risk that such a structure results in important gaps or overlap in activities.

Determining Appropriate Funding Approach. Once the Legislature has identified its climate priorities and made decisions about program structures, it will face choices about the best ways to fund its selected mitigation and adaptation activities. This includes decisions about both funding sources and payment methods. The Governor uses a mix of funding sources for his proposals, including GGRF, General Fund, and bonds (which ultimately are repaid from the General Fund), and proposes a mix of “pay‑as‑you‑go” and bond funding methods. Some factors we recommend the Legislature consider in weighing its funding approach include the following:

- Available GGRF Funding More Limited Than Prior Years. The amount of GGRF funding available for the budget year is a few hundred million dollars less than prior years, and this lower amount could continue over at least the next few years.

- General Fund Faces Many Competing Priorities, but Smart Investments Could Avert Future Costs. Dedicating General Fund to climate change activities means less resources available for other types of state expenditures. However, spending on effective climate adaptation activities now could help prevent higher disaster response and recovery costs in the future.

- Bonds Most Appropriate for Funding Large Capital Projects. Bond funds are best suited for large, discrete capital projects that would ordinarily not be able to be supported by ongoing funding mechanisms and that will last several decades.

- Bonds Result in Long‑Term Commitment of General Fund Resources. After selling bonds, the state must make regular payments from the General Fund towards principal and interest for several decades until they are paid off, regardless of the condition of the state’s fiscal condition or health of the state budget.

Ensuring Legislature Provides Clear Direction to Administration. We believe the Legislature should play a central role in developing the state’s overall strategy in responding to climate change. To do this, it will be important to ensure its priorities and goals are reflected in whatever plan is ultimately adopted. This direction could be provided through adjustments to various budget allocations, as discussed above. In addition, to the extent some of these programs are new and ongoing, the Legislature might want to consider adopting statutory language to ensure the administration implements these ongoing programs in ways that are consistent with legislative priorities. For example, the Governor proposes to expand funding for new climate adaptation research and technical assistance activities without any new statutory direction. The Legislature could consider whether it wants to adopt statutory language that specifies the role of each state agency, what research priorities should be, and/or criteria used to prioritize different projects within a program.

Using Data Collection and Program Evaluation to Inform Future Decisions. Climate mitigation and adaptation are both long‑term activities that are likely to span over multiple decades. Given the long time frames, the Legislature will have an opportunity to update and modify its programs in future years. As a result, it is important to ensure that reliable and useful information about program effectiveness is available in future years to help inform future policy and budget decisions. We encourage the Legislature to consider opportunities to ensure there are adequate data collection and program evaluation structures in place as programs are implemented. In some cases, this might require providing additional resources for program evaluation activities. In our view, the costs of data collection and evaluation activities are often relatively small compared to the overall costs of the program, and the benefits for future decision‑making can be substantial. Moreover, the information collected will be more valuable if the state can establish effective ways to disseminate findings and share lessons learned.

For example, in past reports, we found key limitations in the methods used to evaluate the effects of cap‑and‑trade spending, which makes it more difficult to determine the most cost‑effective way to direct this funding in future years. To address these types of evaluation challenges, the Legislature could consider directing agencies to consult with academic researchers or establish formal structures for independent review of program outcomes. Conducting a robust evaluation of the effects of the state’s GHG mitigation policies is important for informing future policy decisions in California. It also has the potential to provide valuable information to other jurisdictions considering implementing additional mitigation policies about the effectiveness of policies that have been implemented in California.

Developing structures for evaluating and communicating outcomes from investments in climate adaptation is equally important. Because facing the impacts of climate change represents a new challenge for the state, investing state funding in adaptation projects provides an opportunity to learn which strategies work best—as well as which are less effective. Such information can be used to inform and improve future climate response efforts and replicate successful strategies in other locations. However, obtaining and disseminating this important information will require the state ensuring that project implementers monitor and report on adaptation projects after construction is completed.

Cap‑and‑Trade Expenditure Plan

In this section, we assess the Governor’s proposed cap‑and‑trade expenditure plan. The following three sections address the other three major proposals—climate adaptation research and technical assistance, the Climate Catalyst loan fund, and the climate bond.

Background

Cap‑and‑Trade Part of State’s Strategy for Reducing GHGs. One policy the state uses to achieve its GHG reduction goals is cap‑and‑trade. The cap‑and‑trade regulation—administered by the California Air Resources Board (CARB)—places a “cap” on aggregate GHG emissions from large emitters, such as large industrial facilities, electricity generators and importers, and transportation fuel suppliers. Capped sources of emissions are responsible for roughly 80 percent of the state’s GHGs. To implement the program, CARB issues a limited number of allowances, and each allowance is essentially a permit to emit one ton of carbon dioxide equivalent. Entities can also “trade” (buy and sell on the open market) the allowances in order to obtain enough to cover their total emissions. Covered entities can also purchase “offsets” generated from projects that reduce emissions from sources that are not capped. (For more details on how cap‑and‑trade works, see our February 2017 report The 2017‑18 Budget: Cap‑and‑Trade.)

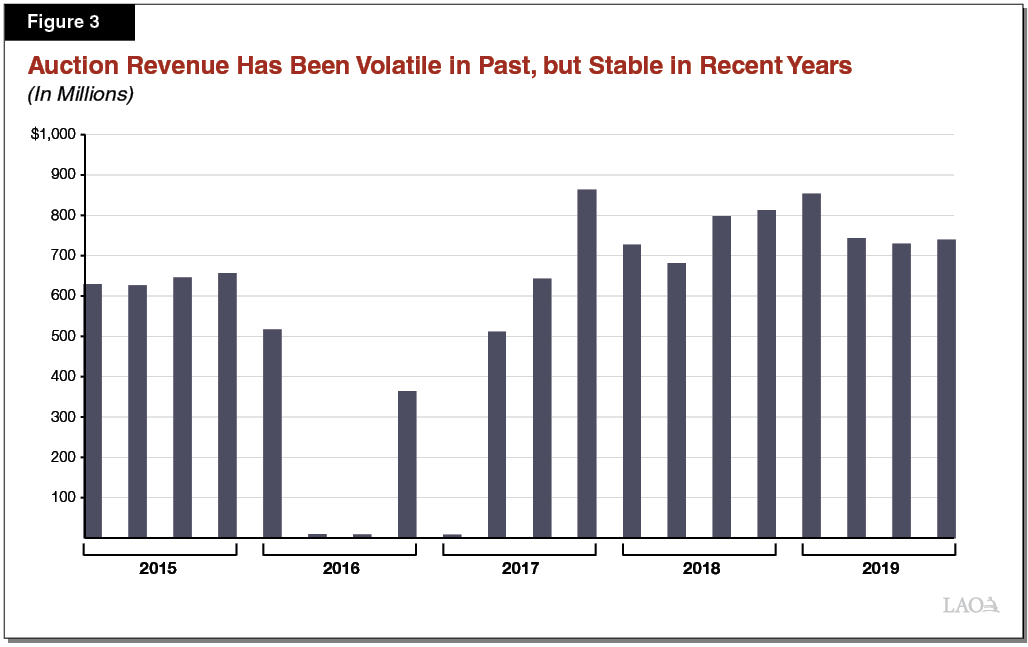

Auction Revenue Has Been Volatile in Past, but Stable Since Program Extension. About half of the allowances issued by CARB are allocated for free to utilities and certain industries, and most of the remaining allowances are sold by the state at quarterly auctions. The allowances offered at quarterly auctions are sold for at least a minimum price—set at $16.68 in 2020—which increases annually at 5 percent plus inflation. Revenue from the auctions is deposited in the GGRF.

Figure 3 shows quarterly state auction revenue since 2015. Quarterly revenue has been relatively consistent, except in 2016 and early 2017 when revenue dropped substantially in a few auctions. This was because very few allowances offered by the state were purchased. Several factors likely contributed to this decrease in allowance purchases, including (1) an oversupply of allowances in the market because emissions were well below program caps and (2) legal uncertainty about the future of the program. The Legislature subsequently passed Chapter 135 of 2017 (AB 398, E. Garcia), which effectively eliminated legal uncertainty about the future of the program by extending CARB’s authority to continue cap‑and‑trade from 2020 through 2030. Since then, quarterly auction revenue has consistently exceeded $600 million—reaching over $800 million in some auctions.

Current Law Allocates Over 65 Percent of Annual Revenue to Certain Programs. Over the last several years, the Legislature has committed to ongoing funding for a variety of programs, including:

- Statutory Allocations to Backfill Certain Revenue Losses. Assembly Bill 398 and subsequent legislation allocates GGRF to backfill state revenue losses from (1) expanding a manufacturing sales tax exemption and (2) suspending a fire prevention fee that was previously imposed on landowners in State Responsibility Areas (known as the SRA fee). Under current law, both of these backfill allocations are subtracted—or taken off the top—from annual auction revenue before calculating the continuous appropriations discussed below. These allocations are roughly $100 million annually.

- Continuous Appropriations. Several programs are automatically allocated 65 percent of the remaining annual revenue. State law continuously appropriates annual revenue (minus the backfills taken off the top) as follows: (1) 25 percent for the state’s high‑speed rail project; (2) 20 percent for affordable housing and sustainable communities grants (with at least half of this amount for affordable housing); (3) 10 percent for intercity rail capital projects; (4) 5 percent for low carbon transit operations; and (5) 5 percent for safe and affordable drinking water, beginning in 2020‑21.

Legislature Has Provided Additional Guidance and Direction on GGRF Spending. The remaining spending—sometimes referred to as “discretionary”—is allocated through the annual budget process. Historically, some of these expenditures have been allocated on a one‑time basis while, for other programs, the Legislature has expressed its intent to fund the programs on a multiyear basis. Multiyear expenditures adopted in recent budgets include:

- $200 million for the Clean Vehicle Rebate Project (CVRP), which provides consumer rebates for purchasing new zero‑emission vehicles (ZEVs). (The 2019‑20 Budget Act provided an additional $38 million in one‑time funding for this program.)

- $165 million for forest health.

- $35 million for prescribed fires and fuel reduction.

- $18 million for healthy soils.

State law establishes other requirements and direction on the use of the funds. For example, at least 35 percent must be spent on projects that benefits disadvantaged communities and/or low‑income households. In addition, AB 398 expressed the Legislature’s intent that GGRF be used for a variety of priorities, including reducing toxic and criteria air pollutants, low carbon transportation alternatives, sustainable agriculture, healthy forests, reducing short‑lived climate pollutants, climate adaptation, and clean energy research.

Governor’s Proposal

Assumes $2.4 Billion of Auction Revenue in 2019‑20 and $2.5 Billion in 2020‑21. Figure 4 summarizes the Governor’s proposed framework for GGRF revenue and expenditures. The budget assumes cap‑and‑trade auction revenue of about $2.4 billion in 2019‑20 and $2.5 billion in 2020‑21. The 2019‑20 amount continues the revenue assumption used when the 2019‑20 budget was adopted last year. The 2020‑21 amount is based on an assumption that all allowances offered by the state will sell at the minimum auction price.

Figure 4

Summary of GGRF Revenues and Expenditures

(In Millions)

|

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

|

|

Beginning Fund Balance |

$543 |

$116 |

|

Revenue |

$2,526 |

$2,630 |

|

Auction revenue |

2,386 |

2,490 |

|

Interest income |

140 |

140 |

|

Expenditures |

$2,953 |

$2,704 |

|

Continuous appropriations |

1450 |

1,527 |

|

Other statutory allocations and administrative costs |

216 |

212 |

|

Discretionary expenditures |

1,287 |

965 |

|

End Fund Balance |

$116 |

$42 |

|

GGRF= Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund. |

||

$965 Million Discretionary Expenditure Plan Spends Most of Available Funds. The budget allocates a total of about $2.7 billion GGRF in 2020‑21 for various programs—including continuous appropriations ($1.5 billion), ongoing statutory allocations and administrative costs ($212 million), and discretionary spending ($965 million). This spending comes from $2.5 billion in anticipated 2020‑21 auction revenue, as well as additional funds from interest earnings and one‑time allocations from the fund balance. Under the Governor’s proposal and revenue assumptions, about $40 million would remain unallocated at the end of 2020‑21.

Lower Spending Amount Largely Reflects Less Carryover Funds From Past Auctions. The overall proposed spending amount from GGRF is about $250 million less than in 2019‑20, largely because there is very little money available in the fund balance at the end of 2019‑20 for use in 2020‑21. In contrast, in recent years, the cap‑and‑trade expenditure plan allocated hundreds of millions of dollars available from large prior‑year fund balances.

Spending Plan Largely Continues Funding for Existing Programs. As shown in Figure 5, funding would largely go to programs that the Legislature has already committed to funding on a multiyear basis—either in statute or prior budgets—as well as some programs that have received one‑time funding in past budgets. Some of the significant differences from last year’s package are:

- Expansion of Climate Research, Technical Assistance, and Adaptation. The plan includes $25 million ongoing to expand various climate research and adaptation activities at OPR, CNRA, and CEC. We describe and assess this proposal in the next section of this report.

- Reduced Funding for CVRP. The plan provides $125 million for CVRP. This is a $75 million reduction relative to the $200 million multiyear appropriation that was approved as part of the 2018‑19 Budget Act. (As previously noted, the 2019‑20 budget includes an additional $38 million for the program on a one‑time basis.)

- No Funding for Some Programs That Previously Received One‑Time Funding. There are several programs that were allocated one‑time GGRF funding in past years that would not receive funding under the Governor’s proposal, including the Transformative Climate Communities, urban greening, and low‑income weatherization.

Figure 5

Cap‑and‑Trade Expenditure Plan

(In Millions)

|

Program |

Department |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

|

Continuous Appropriationsa |

$1,450 |

$1,527 |

|

|

High‑speed rail |

High‑Speed Rail Authority |

$563 |

$587 |

|

Affordable housing and sustainable communities |

Strategic Growth Council |

450 |

470 |

|

Transit and intercity rail capital |

Transportation Agency |

225 |

235 |

|

Transit operations |

Caltrans |

113 |

117 |

|

Safe drinking water programb |

State Water Board |

100 |

117 |

|

Statutory Allocations and Ongoing Administrative Costs |

$216 |

$212 |

|

|

SRA fee backfill |

CalFire/Conservation Corps |

$76 |

$80 |

|

Manufacturing sales tax exemption backfillc |

N/A |

60 |

61 |

|

State administrative costs |

Various |

80 |

71 |

|

Discretionary Spending Commitments |

$1,287 |

$965 |

|

|

Air Toxic and Criteria Pollutants (AB 617) |

$275 |

$235 |

|

|

Local air district programs to reduce air pollution |

Air Resources Board |

245 |

200 |

|

Local air district administrative costs |

Air Resources Board |

20 |

25 |

|

Technical assistance to community groups |

Air Resources Board |

10 |

10 |

|

Forests |

$220 |

$208 |

|

|

Healthy and resilient forests (SB 901) |

CalFire |

165 |

165 |

|

Prescribed fire and fuel reduction (SB 901) |

CalFire |

35 |

35 |

|

Fire safety and prevention legislation implementation (AB 38) |

CalFire |

— |

8 |

|

Urban forestry |

CalFire |

10 |

— |

|

Wildland‑urban interface and other fire prevention |

CalFire |

10 |

— |

|

Low Carbon Transportation |

$485 |

$350 |

|

|

Heavy‑duty vehicle and off‑road equipment programs |

Air Resources Board |

182 |

150 |

|

Clean Vehicle Rebate Project |

Air Resources Board |

238 |

125 |

|

Low‑income, light‑duty vehicles and school buses |

Air Resources Board |

65 |

75 |

|

Agriculture |

$127 |

$88 |

|

|

Agricultural diesel engine replacement and upgrades |

Air Resources Board |

65 |

50 |

|

Dairy methane reductions |

Food and Agriculture |

34 |

20 |

|

Healthy Soils |

Food and Agriculture |

28 |

18 |

|

Other |

$180 |

$84 |

|

|

Workforce training for a carbon‑neutral economy |

Workforce Development Board |

35 |

33 |

|

Climate change research and technical assistance |

Various |

7 |

25 |

|

Waste diversion and recycling |

CalRecycle |

25 |

15 |

|

Energy Corps |

Conservation Corps |

6 |

7 |

|

Coastal adaptation |

Various |

3 |

4 |

|

Transformative Climate Communities |

Strategic Growth Council |

60 |

— |

|

Urban greening |

Natural Resources Agency |

30 |

— |

|

Low‑income weatherization |

Community Services and Development |

10 |

— |

|

Study transition to a carbon‑neutral economy |

CalEPA |

3 |

— |

|

High‑global warming potential refrigerants (SB 1013) |

Air Resources Board |

1 |

— |

|

Totals |

$2,953 |

$2,704 |

|

|

aAllocations based on Governor’s estimate of $2.4 billion in revenue in 2019‑20 and $2.5 billion in 2020‑21. b2019‑20 budget provided $100 million allocation. cGovernor’s estimate. |

|||

|

SRA = State Responsibility Area; CalFire = California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection; N/A = not applicable; AB 617 = Chapter 136 of 2017 (AB 617, C. Garcia); SB 901 = Chapter 626 of 2018 (SB 901, Dodd); AB 38 = Chapter 391 of 2019 (AB 38, Wood); CalRecycle = California Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery; CalEPA = California Environmental Protection Agency; and SB 1013 = Chapter 375 of 2018 (SB 1013, Lara). |

|||

The plan provides an increase in GGRF for local air district administrative costs to implement Chapter 136 of 2017 (AB 617, C. Garcia) from $20 million to $25 million. It is worth noting, however, that the budget does not continue the $30 million from the Air Pollution Control Fund that supported these activities the last couple of years. As a result, on net, the budget provides $25 million less for local air districts’ administrative costs from all fund sources. The budget also provides $200 million in one‑time GGRF funding for local air district incentive programs under AB 617. This is $45 million (18 percent) less than the amount provided last year—a reduction that is slightly less than the overall decrease in discretionary spending commitments (25 percent).

Proposed Language Provides the Administration Authority to Reduce Certain Allocations. Similar to previous budgets, the administration proposes budget bill language (BBL) that (1) restricts certain discretionary programs from committing more than 75 percent of their allocations before the fourth auction of 2020‑21 and (2) gives the Department of Finance (DOF) authority to reduce these discretionary allocations after the fourth auction if auction revenues are not sufficient to fully support all appropriations. DOF must notify the Joint Legislative Budget Committee of these changes within 30 days. This BBL is meant to ensure the fund remains solvent if revenue is lower than estimated. Under the proposal, DOF could reduce funding for air pollution reduction (AB 617) incentives, heavy‑duty and freight equipment programs, transportation equity projects, dairy methane reductions, waste diversion grants and loans, agricultural equipment upgrades, and workforce development. Other discretionary programs would continue to be funded at budgeted levels under this scenario.

Assessment

Overall Revenue Estimates Reasonable, but Slightly Lower Than Our Projections. Our auction revenue estimates are very similar to the administration’s. We estimate revenue will be about $2.6 billion in 2019‑20 and $2.4 billion in 2020‑21. Our estimates assume that all future allowances sell at the minimum auction price—generally consistent with recent market trends. Relative to the administration, our estimates are about $170 million higher over the two‑year period—$250 million higher in the current year and about $80 million lower in the budget year.

There are two primary factors driving these differences. First, the administration has not updated its 2019‑20 revenue estimates to reflect actual revenue from the August 2019 and November 2019 auctions. As a result, the administration’s revenue assumptions for these auctions are about $200 million lower than actuals. Second, we have minor differences in estimates for the number of allowances offered and minimum prices at future auctions. Additional information about revenue from the remaining two auctions in 2019‑20 will be available by late May, at which point the Legislature can reassess the overall amount of resources available.

Size of Proposed Expenditure Plan Reasonable. As discussed above, the administration projects a $42 million fund balance at the end of 2020‑21. This is a relatively low fund balance given the size of the fund and the overall revenue uncertainty. However, two factors mitigate some of the fiscal risks:

- Under our slightly higher revenue estimates, the fund balance would be about $110 million.

- The BBL proposed by the administration would allow DOF to reduce budget allocations if revenue is lower than expected. Up to $125 million of the budget allocations depend on whether future auctions raise adequate revenue.

In our view, given these factors, the overall size of the expenditure plan is reasonable. Under our revenue estimates, the fund balance would be more than 10 percent of estimated annual discretionary revenue. As a percentage of annual revenue, this fund balance would be consistent with many other state funds.

Future Discretionary Revenue Might Not Exceed About $800 Million Annually. If nearly all allowances continue to sell at the floor price, revenue over the next few years will be about $2.4 billion to $2.5 billion annually. After allocating funds for continuous appropriations, other statutory allocations, and ongoing administrative costs, less than $800 million annually would be left for discretionary programs. This is substantially less than the amount that has been allocated in recent years. For example, discretionary allocations were $1.4 billion in 2018‑19 and about $1.3 billion in 2019‑20. Of the $965 million in discretionary spending proposed by the Governor for 2020‑21, $420 million would be ongoing over multiple years.

Explanation for How Administration Prioritized Funding Is Unclear. The cap‑and‑trade expenditure plan reflects the Governor’s spending priorities. However, the rationale and methods used by the administration to prioritize limited funding among different programs is unclear. For example, according to the Governor’s budget summary, it prioritized funding for clean transportation. However, on net, funding for low carbon transportation programs is 36 percent of total discretionary spending, which is slightly lower than the 38 percent provided in last year’s budget. It is unclear how this proposed mix of funding reflects a prioritization of low carbon transportation programs.

Basic Information About Expected Projects and Outcomes Lacking. Similar to last year, the administration has provided limited quantitative information about what outcomes it expects to accomplish with the proposed funding amounts. For example, the administration has not consistently provided information on the expected level of GHG reductions or co‑benefits for each program. The lack of information about expected outcomes limits the Legislature’s ability to evaluate the merits of each program, making it more difficult to ensure funds are allocated in a way that is consistent with its priorities and achieves its goals most effectively. By not having this information before programs are implemented, it also limits the Legislature’s ability to hold departments accountable when evaluating the performance of these programs after they are implemented. (State law requires DOF to produce an annual report in March that should contain some information on outcomes associated with prior GGRF expenditures.)

Reduction to CVRP Program Inconsistent With Recent Legislative Action. At various times over the last few years, CARB has implemented a rebate waitlist for CVRP because funds were insufficient to meet demand. This created uncertainty for consumers considering purchasing ZEVs and businesses selling ZEVs. As part of the 2018‑19 budget package, the Legislature expressed intent to provide at least $200 million annually for five years to CVRP. This was meant to provide CARB with greater certainty about the CVRP budget so it could structure the program accordingly. CARB recently made changes to the program intended to help it stay within budget and avoid waitlists as demand for the program continues to grow. For example, CARB lowered rebates for most vehicles by $500 and targeted rebates to ZEVs that have a price of less than $60,000.

The proposed reduction in funding for CVRP creates the type of uncertainty that the Legislature was trying to avoid. If adopted, CARB would have to make additional adjustments to reduce costs in the program. For example, based on CARB projections of CVRP demand in 2020‑21, rebates would have to be cut nearly in half to stay within the proposed budget (assuming no other programmatic changes are made).

Furthermore, state law establishes a goal of 1 million ZEVs in California by 2023, and executive orders establish goals of 1.5 million by 2025 and 5 million by 2030. Currently, there are roughly 600,000 ZEVs in California. The administration has not provided an assessment of (1) how the proposed reduction CVRP will affect the number of ZEVs purchased and (2) whether such a change will adversely affect the state’s ability to meet its ZEV goals.

Recommendations

Ensure Multiyear Discretionary Expenditures Do Not Exceed $800 Million. If cap‑and‑trade allowance prices remain near the minimum over the next few years, annual auction revenue would not support annual discretionary spending much above $800 million. As a result, we recommend the Legislature ensure its multiyear GGRF spending commitments do not exceed about $800 million annually. As mentioned above, the Governor’s budget includes $420 million in multiyear discretionary GGRF spending commitments—substantially less than $800 million. However, although the remaining $545 million allocated to discretionary programs are technically budgeted on a one‑year basis, all of these programs have received consecutive years of funding, and many of the program activities are expected to continue into the future. For example, $235 million is allocated to AB 617 activities on a one‑time basis even though many of the activities are expected to continue in the future. This adds a long‑term cost pressure on the fund that is not reflected in the $420 million multiyear allocations in the Governor’s budget. The Legislature might want to identify the core discretionary programs it would like to fund on a multiyear basis with a budget of $800 million annually.

Direct Administration to Provide Additional Information on Expected Outcomes. We recommend the Legislature direct the administration to report at spring budget hearings on key metrics and outcomes it expects to achieve with new discretionary spending. This information would help the Legislature evaluate the merits of these proposals and, in the future, hold departments accountable by comparing the projected outcomes to the actual outcomes achieved. If the administration is unable to provide such information for certain programs, the Legislature could consider adjusting allocations to those programs downward accordingly.

Allocate Funds According to Legislative Priorities. When allocating funds among different programs, we recommend the Legislature first consider its highest priorities. These priorities could include such things as GHG reductions, improved local air quality, forest health and fire prevention, and climate adaptation. As discussed above, these decisions about priorities should take into account other funding sources that are available and other regulatory programs aimed at achieving the same goals. For example, the state has a wide variety of regulatory programs aimed at reducing GHG emissions. These programs have been the primary drivers of emission reductions in the state and are expected to be the primary drivers of future reductions. As a result, the Legislature could consider giving greater priority to adaptation activities or local air pollution activities that could benefit from state funding.

Once the Legislature has identified its priorities, it can then allocate the funds to the programs that it believes will achieve those goals most effectively. For example, to the extent the Legislature considers GHG emission reductions the highest‑priority use of the funds, the Legislature will want to allocate funding to programs that achieve the greatest GHG reductions. As we have discussed in previous reports (The 2018‑19 Budget: Resources and Environmental Protection, for example), determining which programs achieve the greatest amount of net GHG reductions is challenging for a variety of reasons. Many of the spending programs interact with other regulatory programs in ways that make it complicated to evaluate the net GHG effects of any one program. However, even with this uncertainty, the Legislature might want to consider focusing on spending strategies that are generally more likely to reduce emissions in a cost‑effective way. This could include, for example, focusing on reductions from sources of emissions that are not subject to the cap‑and‑trade regulation or other regulations. The Legislature could also consider targeting other “market failures” that are not adequately addressed by carbon pricing, such as promoting innovation through research and development programs.

In addition, since California represents only about 1 percent of global GHG emissions, some of the most significant impacts California programs will have on global GHGs could depend on the degree to which state programs (1) help promote the development of new technologies that can be deployed in other jurisdictions and (2) influence the adoption of policies and programs in other parts of the country and world. As a result, the Legislature might want to evaluate each program, in part, based on its assessment of its potential effects on actions elsewhere. For example, state programs that effectively serve as policy demonstrations for other jurisdictions and programs that promote advancements in GHG‑reducing technologies that can be used in other jurisdictions could have a more substantial long‑term effect on global GHG emission reductions.

Consider Other Funding Sources for High‑Priority Programs. The Legislature might want to consider utilizing other funding sources to supplement spending on the climate‑related activities it prioritizes. For example, the Governor proposes $51 million one time from the Alternative Renewable Fuel and Vehicle Technology Fund (ARFVTF) for ZEV fueling infrastructure. This is in addition to the roughly $80 million in annual baseline funding for CEC that goes to ZEV infrastructure, and hundreds of millions of dollars in investor‑owned utility (IOU) funding going to ZEV infrastructure. So, to the extent that the Legislature prioritized transportation‑related programs (such as CVRP) more than is reflected in the Governor’s spending plan, it could consider using ARFVTF to support these activities in lieu of targeting them towards ZEV fueling infrastructure.

Climate Research and Technical Assistance Funding

Background

New Program to Provide Technical Assistance to Under‑Resourced Communities Seeking State Grants. In 2018, the Legislature passed Chapter 377 (SB 1072, Leyva), creating a program under SGC intended to increase access by under‑resourced communities to available grant funding for climate change mitigation and adaptation projects. This “Regional Climate Collaboratives” program will provide technical assistance and start‑up grants to community groups to build the expertise, partnerships, and local capacity necessary to develop successful applications for state funding programs. For example, these start‑up grants might be used to host community meetings and grant writing workshops. While it has funded three positions at SGC to begin designing the program, the Legislature has not yet allocated funding to provide grants to local collaborative groups as required by SB 1072.

Integrated Climate Adaptation and Resilience Program (ICARP) Intended to Help Coordinate State’s Climate Response. Chapter 606 of 2015 (SB 246, Wieckowski) established ICARP at OPR. The program is intended to develop a coordinated response to the impacts of climate change across the state and has two statutorily required components. First, a Technical Advisory Council was created to help OPR and the state improve and coordinate climate adaptation activities. Second, OPR has created a searchable online public database of adaptation and resilience resources known as the State Adaptation Clearinghouse. The Clearinghouse includes resources for state and local agencies, such as local plans, educational materials, policy guidance, data, research, and case studies. The state currently spends $283,000 annually from the General Fund for two staff to oversee ICARP activities.

State Has Undertaken Several Climate Change Research Initiatives. The state has funded and participated in multiple climate change focused research initiatives over the past several years. These include ongoing state‑funded scientific research programs looking into the effects of climate change run by several state departments, including the Delta Stewardship Council, Ocean Protection Council, and Department of Water Resources (DWR). Some other key state‑led research efforts have included:

- California Climate Change Assessments. The state has undertaken four comprehensive climate change assessments. Each assessment included a series of reports summarizing the current scientific understanding of possible climate change risks and impacts to the state and identifying potential suggestions to inform policy actions. The Legislature has not adopted statute requiring or guiding these assessments, nor has it provided much funding for them through explicit budget appropriations. Rather, the first assessment in 2006 was carried out in response to an executive order, and subsequent updates in 2009, 2012, and 2018 were undertaken as priorities of prior administrations. These assessments were supported primarily using existing staff and funds from various state departments (including the CEC‑funded research programs described below), as well as probono contributions from researchers and other partners. (The state did provide $5 million from the Environmental License Plate Fund in 2014‑15 to support development of the fourth assessment.)

- SGC Climate Change Research Program. Since 2017‑18, SGC has received three one‑time GGRF appropriations totaling $34 million to provide grants for research to inform state and local responses to climate change. The program’s first two grant rounds awarded funding to a total of 14 projects, mostly led by University of California (UC) campuses. (SGC is in the process of soliciting applications for a third round of grants for the remaining funding.) According to SGC, the Climate Change Research program focuses on projects that “aim to both advance the implementation of California’s climate policies and result in real benefits to disadvantaged and climate‑vulnerable California communities.” For example, one funded project is developing tools that state agencies can use to assess whether vulnerable populations might be displaced by potential climate change strategies and policies.

- Energy Research by CEC. CEC has several research initiatives intended to help make California’s energy system more clean, reliable, safe, and affordable. These are funded through charges to electricity and natural gas users. For example, the Electric Program Investment Charge program spends more than $130 million annually in research to promote clean energy technologies and help meet the state’s energy and climate goals. The CEC used funding from its research programs to fund a large portion of the first four statewide climate change assessments.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor proposes to spend a total of $25 million annually from 2020‑21 through 2024‑25—for a total of $125 million—from the GGRF for climate change research and technical assistance activities that fall into four categories. These categories are summarized in Figure 6 and described in more detail below. As noted earlier, this collection of initiatives represents the most significant new proposal within the Governor’s GGRF package. While the $25 million is proposed on an ongoing basis, the administration’s spending plan shifts the allocations among the four categories over the next five years, as shown in the figure. The administration indicates that after 2024‑25 it would come back to the Legislature with a new budget proposal for approval of specific uses for these funds in future years.

Figure 6

Governor’s New Climate Change Research and Technical Assistance Proposals

(In Millions)

|

Category |

Department |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

Totals |

|

SB 1072a implementation |

SGC |

$5.0 |

$8.0 |

$6.0 |

$8.0 |

$8.0 |

$35.0 |

|

Expand ICARP activities |

OPR |

7.4 |

6.8 |

6.5 |

6.7 |

6.7 |

34.0 |

|

5th climate change assessment |

OPR, SGC, CNRA, CEC |

7.6 |

3.2 |

11.7 |

3.3 |

3.3 |

29.2 |

|

Climate Change Research program |

SGC |

5.0 |

7.0 |

0.8 |

7.0 |

7.0 |

26.8 |

|

Totals |

$25.0 |

$25.0 |

$25.0 |

$25.0 |

$25.0 |

$125.0 |

|

|

aChapter 377 of 2018 (SB 1072, Leyva). SGC = Strategic Growth Council; ICARP = Integrated Climate Adaptation and Resilience Program; OPR = Governor’s Office of Planning and Research; CNRA = California Natural Resources Agency; and CEC = California Energy Commission. |

|||||||

Implements SB 1072 to Expand Access to State Funding by Under‑Resourced Communities ($5 Million). The Governor proposes $5 million in 2020‑21 ($35 million total over the next five years) for SGC to implement the requirements of SB 1072. As noted earlier, this legislation—for which programmatic funding has not yet been appropriated—requires SGC to develop a program and provide grants to local groups to form regional climate collaboratives. These groups are intended to help build capacity for under‑resourced communities to develop climate‑response projects and successfully apply for and receive state grant awards. Of the proposed funding, $495,000 per year would support three staff at SGC with the remainder being used for capacity‑building grants to local collaborative groups.

Expands Scope of Existing ICARP Activities to Help Guide State’s Climate Change Response ($7.4 Million). The Governor would provide $7.4 million in 2020‑21 ($34 million total over five years) to expand the existing ICARP activities at OPR. As noted above, ICARP was established in statute with two primary duties: convening a Technical Advisory Council to help inform the state’s climate response and creating and managing a web‑based clearinghouse of adaptation resources. The Governor’s proposal would fund four OPR staff and the following additional activities:

- Establish Regional Resilience Coordinators. The proposal would provide $5 million annually for grants to fund staff at local government or nongovernmental agencies located in approximately ten regions around the state. These coordinators would support local adaptation projects and planning efforts and provide input to the ICARP Technical Advisory Council.

- Develop Vulnerability Assessment Tools. OPR would enter into contracts to develop standardized online tools that state and local entities could use to identify climate risks and vulnerabilities for communities around the state.

- Develop Resilience Metrics. OPR would enter into contracts to develop “measurable resilience outcomes and metrics” to help guide the state in prioritizing its climate adaptation efforts and enable the state to track its progress in increasing resilience.

- Convene Working Groups. OPR staff would organize multiple working groups to provide input to the ICARP Technical Advisory Council, including a science advisory group that could provide scientific expertise and guidance to inform state efforts and identify research gaps that the state should address.

Develops Fifth California Climate Change Assessment ($7.6 Million). The Governor proposes providing $7.6 million in 2020‑21 ($29.2 million total over five years) to conduct the Fifth California Climate Change Assessment. This would be the first time the state budget provides substantial funding explicitly for this research initiative. Similar to the fourth assessment that was completed in 2018, this update would include a series of reports summarizing the most recent climate science relevant to California, including a statewide summary report, regional reports tailored to issues and data relevant to different areas of the state, and a series of technical reports on selected topics. (The first three assessments did not include regional reports.) The proposal also includes funding to expand tribal outreach and involvement in the research (to be coordinated by CEC), as well as for outreach efforts to solicit input on the reports and to disseminate their findings. The work to develop these reports would be managed across four state entities—OPR, SGC, CNRA, and CEC—and includes funding for six positions (two each at OPR and CEC, and one each at SGC and CNRA). In addition to the requested funding from GGRF, the assessment would be supported by up to $8.8 million in CEC’s energy‑related research funding.

Continues Funding for SGC’s Climate Change Research Program ($5 Million). The Governor’s proposal includes $5 million in 2020‑21 ($26.8 million total over five years) for the SGC Climate Change Research program. As noted above, this program has received GGRF in each of the last three years totaling $34 million. The administration states that SGC will conduct outreach to stakeholders to identify specific areas of focus for future rounds of grants from this program and try to identify research gaps not being funded by other sources. Of the proposed funding, $540,000 per year would be used to support three positions at SGC to oversee the grant program. Based on the average grant amounts from prior years, we estimate the proposed funding might support approximately 12 new research grants over the next five years depending upon the sizes of the projects and grants.

Assessment

Proposals Represent Significant Expansion of State’s Climate‑Related Research and Technical Assistance Efforts. Providing an additional $25 million in ongoing funding for climate adaptation research and technical assistance activities would be a significant increase compared to existing funding and state‑level efforts. As noted above, the state currently supports only two staff to work on the relatively narrowly scoped ICARP program, has not appropriated significant funding from the state budget for previous climate assessments, and has provided just limited‑term funding for climate change research at SGC.

Proposals Focus on Important State‑Level Activities. Given the significant challenges that the impacts of climate change pose for California, we believe the Governor’s focus on increasing the state’s adaptation efforts has merit. While much of the work to prepare for the effects of climate change needs to happen at the local level, it is appropriate for the state to help support those efforts. The state can take advantage of its economies of scale and provide guidance to help ensure that local governments’ adaptation efforts are both cost‑effective and consistent. As such, we find that the types of activities the Governor includes in his proposals—conducting and disseminating research, developing tools that can be widely used, clarifying statewide priorities and setting measurable objectives, and assisting vulnerable and under‑resourced communities—are worthwhile areas on which to focus state‑level efforts.

Proposals Are Not Only Approach for Expanding State Climate Adaptation Activities. While the types of state‑level activities the Governor proposes are reasonable, his package of proposals is not the only way the state can effectively respond to climate change. The Governor’s proposed funding increase provides an important opportunity for the state—and the Legislature—to set an agenda for how it wants to enhance and expand California’s state‑level climate adaptation efforts in the coming years. Specifically, the proposed augmentation creates a decision‑making juncture around (1) what climate adaptation research and technical assistance activities the state wants to undertake, (2) how much the state wants to spend on those activities, and (3) which state‑level entities should undertake them. The Governor’s proposal represents one approach to answering these questions, but an alternative package with a somewhat different design could also be reasonable and help achieve key statewide climate adaptation objectives.

For example, the Legislature could develop a package that places a comparatively lesser focus on research—given all of the climate research being conducted by other state departments and universities—and greater emphasis on providing technical assistance and support to local stakeholders. In conducting research for our recent report, Preparing for Rising Seas: How the State Can Help Support Local Coastal Adaptation Efforts, interviewees repeatedly cited a lack of—and desire for—a state‑level entity upon which they might be able to call for advice, technical assistance, comparison data, and real‑world examples to help inform their adaptation decisions. The Governor’s proposal to fund regional climate coordinators through ICARP could help address this need, but so too would establishing a state‑funded center of climate expertise upon which local stakeholders could rely for support.

Additionally, the Governor’s proposed funding level of $25 million does not represent a “right” number for state‑level climate research and technical assistance efforts—the Legislature could provide a greater or lesser amount of funding depending on what is needed to support the activities it deems to be priorities. Moreover, the Governor assigns most of his proposed climate response activities to OPR and SGC. While these offices have been involved in the state’s nascent adaptation efforts, so too have CNRA and several of its departments. The Legislature could consider a different governance structure around which to organize augmented climate adaptation technical assistance and research efforts. For example, it could follow a more centralized approach—such as by tasking most responsibilities to one department—or a more decentralized approach—such as by assigning discrete initiatives and funding to a wider array of state departments.

Lack of Statutory Framework for New Policy Initiatives Limits Legislative Direction and Oversight. The Governor does not propose statutory language to implement any of the components of this new $25 million GGRF proposal. While the Legislature frequently grants the administration broad authority to implement programs through budget appropriations, such an approach does not provide the same level of legislative input and oversight as legislation. Clarifying program goals and design components in statute provides more specific direction to the administration about how the program should be implemented in a way that reflects legislative priorities. Moreover, such statutory guidance gives the Legislature—and the public—a legal framework for holding the administration accountable in following those directions.

The Governor’s various proposals would represent a significant expansion of the state’s climate adaptation efforts and would make several new or previously limited‑term activities into ongoing state programs. Given the Legislature’s considerable interest in responding to climate change—and its previous involvement in setting goals for climate mitigation efforts—it may not want to cede full discretion to the administration by establishing these efforts only through the budget without accompanying statute to guide their implementation. We believe a greater emphasis on climate adaptation in state policy warrants a more explicit role for the Legislature.

For example, the Governor’s proposal to expand ICARP activities without a statutory framework would mean that this program would have some of its activities explicitly directed by statute, and other activities—with significantly greater levels of associated funding—guided primarily by OPR’s discretion. A more consistent approach would be to define all of the program’s funded responsibilities in statute. The Legislature could also adopt statute that helps to direct those activities, such as by specifying the types or categories of adaptation goals on which ICARP should focus when developing the proposed resilience metrics. Similarly, it might want to specify areas of focus for climate research, including the Fifth California Climate Change Assessment, to help guide future state actions. This could include specifying that the research identify the state’s highest climate vulnerabilities and the best approaches to prioritize and “buy down” that risk.

Multiple Research Initiatives Might Make Strategic Coordination Difficult. The Governor’s proposal includes funding for three separate climate change research programs—(1) the Fifth California Climate Change Assessment, for which four separate state entities would contract for original research on a number of topics; (2) the SGC Climate Change Research program, intended to fund original research projects that address climate knowledge gaps and have a particular focus on vulnerable communities; and (3) a new science advisory workgroup that would synthesize existing climate research to help guide decisions by the state and the ICARP Technical Advisory Council. These proposals are in addition to ongoing climate‑related research related to the energy sector at CEC, as well as other existing state‑level climate research managed by state departments such as the Delta Stewardship Council, Ocean Protection Council, and DWR. Moreover, many academic institutions around the state—including the UC system, Stanford, and the University of Southern California—are also making climate change a central focus of their research. As noted above, we believe conducting scientific research to inform adaptation decisions at both the state and local levels is both an appropriate and worthwhile activity for the state to take on. Because of their scale, state‑level efforts often are more cost‑effective than individual jurisdictions attempting to conduct their own research, and can help ensure that adaptation efforts undertaken across the state are informed by data that is consistent. However, the multiple initiatives and departments associated with the Governor’s proposal could make it difficult to ensure that state funding for research is used in the most effective and strategic manner. Careful coordination would be necessary to ensure these numerous research efforts are complementary and not duplicative, each initiative and managing department has a specific and distinct focus, and the selected research topics are broadly beneficial and applicable for informing state and local adaptation decisions.

Recommendations

Expand Climate Adaptation Activities With Approach That Reflects Legislative Priorities. We recommend the Legislature increase state‑level efforts related to climate adaptation with a package that (1) includes the climate adaptation research and technical assistance activities it views to be the highest priorities, (2) provides funding sufficient to support those activities, and (3) assigns the activities to the state‑level entities it believes are best suited to manage their implementation. While the Governor’s proposals are reasonable, the Legislature could adopt an equally worthwhile mix of activities with a somewhat different emphasis. For example, the Governor’s package places a significant emphasis on research. As noted above, our interviews with local governments seeking to implement climate adaptation projects suggest a strong interest across the state for increased technical assistance that is user‑friendly and easily accessible. The Legislature could respond to that need and increase funding for technical assistance—such as by establishing an adaptation information center upon which stakeholders could call when needing support—by spending somewhat less on climate research compared to the Governor.

Additionally, as we discuss in the “Climate Bond” section later in this report, the Legislature could use some of these GGRF monies for activities to help improve how bond funds are used. Such activities could include designing tools to evaluate the anticipated cost‑effectiveness of potential projects seeking bond funds, or supporting development of regional climate adaptation plans that local collaborative groups could use to prioritize bond‑funded projects with the greatest regional benefits.

Delineate Key Climate Policy Goals and Activities in Statute. We recommend the Legislature adopt statutory language for any high‑priority climate adaptation activities over which it wants to provide guidance and assure greater accountability. If the Legislature decides to provide funding to significantly expand the state’s climate adaptation research and technical assistance activities, it will also want to ensure it has a role in designing and overseeing how these efforts will be implemented. Adopting a statutory framework describing those activities and their intended outcomes is the best avenue available to the Legislature to express its priorities and ensure they are reflected in the administration’s program‑specific implementation decisions. In particular, we recommend maintaining a consistent approach with ICARP and adopting statute to define any expansion of that program’s activities. Additionally, if the Legislature opts to expand the state’s climate change research efforts—by adopting the Governor’s proposals or a modified approach—it could ensure these efforts will investigate key issues that are priorities for the Legislature by specifying such direction in statute. Statutory language could also clarify the specific focus and scope of each of the various state‑level research efforts to try to help avoid duplication.

Climate Catalyst Revolving Loan Fund

Background

IBank Provides Financing for Variety of Private and Public Projects. IBank is a general‑purpose finance authority created in 1994 with a broad mandate to help finance public infrastructure and private development. Its operations generally are funded from the interest earnings of its financing programs. IBank is governed by a five‑member Board of Directors. IBank administers a number programs that finance private and public projects, including projects with climate‑related benefits. Specifically, IBank administers the following programs: