LAO Contact

- Managing Principal Analyst, Resources and Environmental Protection

- Parks, Forestry and Fire

- Cap-and-Trade

- Water, Fish and Wildlife, State Lands

- Water, Conservation

- Energy

February 14, 2018

The 2018-19 Budget

Resources and Environmental Protection

- Overview of Governor’s Budget

- Cross‑Cutting Issues

- California Conservation Corps

- Department of Fish and Wildlife

- Department of Parks and Recreation

- Department of Forestry and Fire Protection

- Department of Water Resources

- State Lands Commission

- Department of Conservation

- California Energy Commission

- State Water Resources Control Board

- Summary of Recommendations

Executive Summary

In this report, we assess many of the Governor’s budget proposals in the resources and environmental protection areas and recommend various changes. Below, we summarize our major findings and recommendations. We provide a complete listing of our recommendations at the end of this report.

Budget Provides $11 Billion for Programs

The Governor’s budget for 2018‑19 proposes a total of $10.5 billion in expenditures from various sources—the General Fund, various special funds, bond funds, and federal funds for programs administered by the Natural Resources ($6.3 billion) and Environmental Protection ($4.2 billion) Agencies. (These figures include the administration’s proposed spending plans for cap‑and‑trade auction revenues and zero‑emission vehicle (ZEV) infrastructure, which were released after the Governor’s budget.) The total funding level in 2018‑19 reflects numerous changes compared to 2017‑18, the most significant of which include (1) decreased bond spending of $3 billion, largely attributable to how prior‑year bond expenditures are accounted for in the budget; (2) an increase of $989 million to fund projects authorized under Proposition 68, which will appear on the June 2018 statewide ballot; and (3) a net reduction of $587 million from the General Fund, in large part due to one‑time funding provided in 2017‑18 related to emergency firefighting and recovery costs.

Cap‑and‑Trade Spending Plan Based on Reasonable Revenue Estimates

The administration assumes $2.4 billion in cap‑and‑trade auction revenue in 2018‑19. While the Governor’s revenue estimates are slightly lower than ours, we find them to fall within a reasonable range. Importantly, the Legislature’s recent extension of the cap‑and‑trade program through 2030 should result in additional revenue stability compared to prior years, though there continues to be potential for volatility. Based on the administration’s revenue estimate (and a projected year‑end fund balance in 2017‑18), the Governor proposes to spend $2.8 billion from these funds in 2018‑19 (including $1.3 billion in discretionary spending). The administration’s spending plan is similar to that adopted for the current year, though it includes a couple of new programs. The plan also proposes to make $232 million of the spending ongoing, mostly for light‑duty ZEV rebates ($200 million). As we have in our past reports on cap‑and‑trade, we recommend that the Legislature ensure that the spending plan is consistent with its highest priorities for this revenue, which could include greenhouse gas reductions, as well as such things as local air pollution reductions and/or climate adaptation.

Governor Proposes New Programs

Implementation of Resources Bond. The Governor’s 2018‑19 budget provides $989 million from Proposition 68 (authorized by Chapter 852 of 2017 [SB 5, de León]) for various resources and environmental protection departments to administer resources‑related programs, such as to expand and rehabilitate local parks and implement habitat restoration projects. With only a couple of exceptions, we find the administration’s funding plan for 2018‑19 to be reasonable. However, we recommend small modifications to a couple of programs and that the administration report to the Legislature on a long‑term funding plan.

Safe and Affordable Drinking Water Fund. The Governor proposes new charges on drinking water customers and certain agricultural entities to generate revenue to implement a new financial assistance program to address unsafe drinking water, particularly in small and disadvantaged communities. When fully implemented, these charges are expected to generate roughly $150 million annually. In this report, we identify three issues for the Legislature to consider as it deliberates this proposal: (1) consistency with the state’s human right to water policy, (2) uncertainty about the estimated revenues that would be generated by the proposal and the amount of funding needed to address the problem, and (3) consistency with the polluter pays principle.

Ventura Training Camp. The proposed budget provides a total of $9 million from the General Fund to the Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, California Conservation Corps (CCC), and California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation to create a new firefighting training program for 80 parolees. According to the administration, the primary purpose of the proposal is to reduce parolee recidivism. We recommend rejection of the proposal because there is little evidence that the plan would be a cost‑effective way to achieve the stated goal. Instead, to the extent that the Legislature wanted to prioritize recidivism reduction programs, there are likely to be evidence‑based programs that could serve many more individuals than what is proposed.

Budget Includes Significant Program Expansions

ZEV Infrastructure. The administration proposes to spend $235 million for the California Energy Commission—an increase of $199 million—in 2018‑19 from various special funds to install electric vehicle chargers and hydrogen refueling stations throughout the state. The proposed spending plan would provide a total of $900 million over eight years and is intended to support the Governor’s goal of having 5 million ZEVs on California roads by 2030. In considering the proposal, we recommend the Legislature direct the administration to provide additional information regarding how it developed its funding estimate, expected outcomes, risks, and efforts to coordinate across state programs.

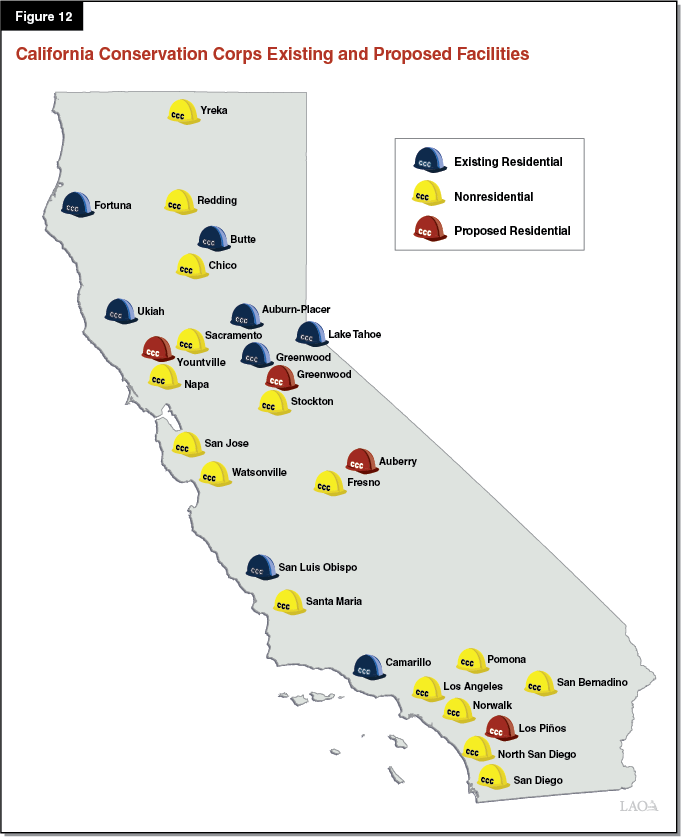

CCC Residential Facilities. The Governor’s budget plan proposes to expand CCC’s residential program over the coming years by building four new facilities. The budget includes $10 million from the General Fund for the acquisition and initial planning stages of these projects, which are estimated to cost a total of $185 million to complete. The decision about whether to take the initial steps towards a major expansion of CCC residential centers is ultimately a policy decision for the Legislature. We recommend the Legislature (1) wait for more information before approving funding for four new residential centers and (2) require CCC to provide reporting on corpsmember outcomes.

Department of Fish and Wildlife (DFW) Funding Augmentation. The Governor proposes providing $51 million in new funding for DFW from three sources—tire recycling fees, vehicle registration and driver’s license fees, and the General Fund—to (1) address an ongoing operating shortfall ($20 million) and (2) expand several existing activities ($31 million). We recommend the Legislature approve the additional funding to address the funding shortfall and provide some level of additional augmentation for activities that reflect legislative priorities. However, we recommend rejecting the proposed use of tire fees, approving only the level of Motor Vehicle Account funding that DFW can provide evidence would support vehicle‑related workload, and relying on General Fund and fees for the remaining augmentations.

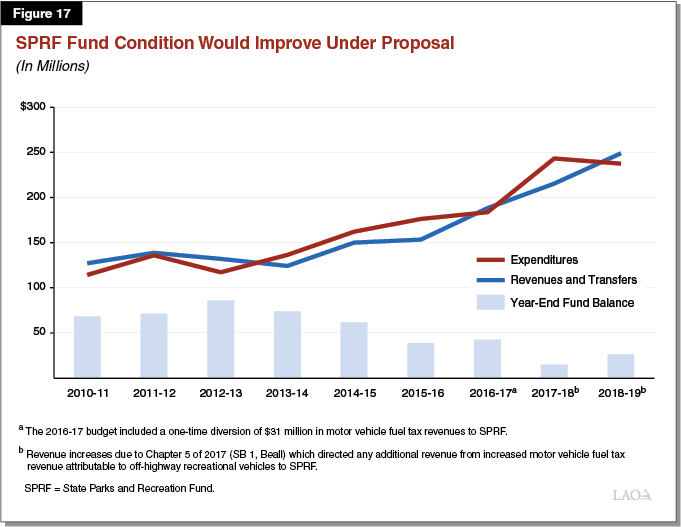

Parks and Recreation Program Expansion. Under recent legislation, the State Parks and Recreation Fund (SPRF) will receive additional ongoing revenue—$79 million in 2018‑19—from an increase in the state’s fuel taxes associated with off‑highway vehicles. We find that the administration’s proposal to utilize these funds to (1) address the SPRF structural deficit and build a reserve, (2) increase service levels at state parks, and (3) continue certain activities begun in the current year is reasonable. However, we recommend that the Legislature identify park services and programs that it prioritizes and adopt a budget package that reflects those priorities.

Overview of Governor’s Budget

Total Proposed Spending of $10.5 Billion. The Governor’s budget for 2018‑19 proposes a total of $10.5 billion in expenditures from various sources—the General Fund, various special funds, bond funds, and federal funds—for programs administered by the Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Agencies. This total includes $6.3 billion for natural resources departments and $4.2 billion for environmental protection departments. (These amounts include the Governor’s spending plans for cap‑and‑trade auction revenues and zero‑emission vehicle (ZEV) infrastructure, which were released after—and, therefore, not included in—the Governor’s budget.)

Half of Natural Resources Funding From General Fund. As shown in Figure 1, almost half—$3 billion—of the $6.3 billion proposed for natural resources departments is from the General Fund. Another $1.8 billion (28 percent) is from special funds, and $1.2 billion (19 percent) is from bond funds. Of the total proposed spending, $4.8 billion (76 percent) is to administer state programs, and most of the remainder is for local assistance—generally grants to local governments and nonprofits.

Figure 1

Natural Resources Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Expenditures |

2016‑17 |

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

Change From 2017‑18 |

|

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Total |

$5,039 |

$8,870 |

$6,266 |

‑$2,603 |

‑29% |

|

By Department |

|||||

|

Department of Forestry and Fire Protection |

$1,305 |

$2,181 |

$1,755 |

‑$425 |

‑20% |

|

Department of Parks and Recreation |

480 |

868 |

1,093 |

224 |

26 |

|

General obligation bond debt service |

1,025 |

984 |

993 |

9 |

1 |

|

Energy Commission |

396 |

684 |

604 |

‑79 |

‑12 |

|

Department of Fish and Wildlife |

431 |

438 |

529 |

92 |

21 |

|

Department of Water Resources |

548 |

2,007 |

475 |

‑1,532 |

‑76 |

|

Wildlife Conservation Board |

94 |

496 |

132 |

‑364 |

‑73 |

|

Department of Conservation |

124 |

142 |

126 |

‑16 |

‑11 |

|

California Conservation Corps |

94 |

123 |

125 |

2 |

2 |

|

Natural Resources Agency |

312 |

333 |

123 |

‑209 |

‑63 |

|

State Lands Commission |

32 |

45 |

98 |

53 |

117 |

|

Other resources programsb |

199 |

570 |

212 |

‑358 |

‑63 |

|

By Funding Source |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$2,726 |

$3,586 |

$3,034 |

‑$552 |

‑15% |

|

Special funds |

1,271 |

2,120 |

1,769 |

‑351 |

‑17 |

|

Bond funds |

885 |

2,794 |

1,171 |

‑1,623 |

‑58 |

|

Federal funds |

157 |

370 |

292 |

‑77 |

‑21 |

|

By Purpose |

|||||

|

State operations |

$4,174 |

$5,689 |

$4,774 |

‑$915 |

‑16% |

|

Local assistance |

556 |

2,135 |

1,243 |

‑892 |

‑42 |

|

Capital outlay |

309 |

1,046 |

250 |

‑796 |

‑76 |

|

aIncludes Governor’s cap‑and‑trade and zero‑emission vehicle infrastructure spending plans, which were not included in the Governor’s January 10 budget. bIncludes state conservancies, Coastal Commission, and other departments. |

|||||

Most of Environmental Protection Funding From Special Funds. As shown in Figure 2, a large majority of funding for environmental protection programs—$3.6 billion (86 percent)—is from special funds. Only $84 million (2 percent) of environmental protection spending is proposed from the General Fund. Over 60 percent of the proposed funding in the budget year is proposed for local assistance.

Decrease From 2017‑18 Largely Reflects Technical Changes. Proposed 2018‑19 spending is significantly lower than estimated expenditures in 2017‑18 for both natural resources and environmental protection departments ($2.6 billion and $2.1 billion, respectively). This includes significant spending decreases in spending from bond funds, special funds, and the General Fund. However, these changes largely reflect certain technical budget adjustments rather than significant programmatic changes.

- Bonds From Prior Years. Proposed bond funds are estimated to decline by a total of $3 billion, slightly more than half associated with resources programs. Much of this apparent budget‑year decrease is related to how bonds are accounted for in the budget, making year‑over‑year comparisons difficult. Specifically, bond funds that were appropriated but not spent in prior years are assumed to be spent in the current year. The 2017‑18 bond amounts will be adjusted in the future based on actual expenditures.

- Special Fund Programs. The 2018‑19 proposed spending level reflects reduced special fund expenditures of about $1 billion in natural resources and environmental protection departments. While about one‑quarter of this is related to lower year‑over‑year proposed spending from cap‑and‑trade auction revenues, most of the remaining reduction is related to one‑time projects and technical adjustments. In particular, the current‑year spending level for the California Air Resources Board (CARB) includes $413 million for the construction of a new testing lab in Southern California. In addition, the budget includes a decrease of about $170 million in spending from two California Energy Commission (CEC) special funds—the Electric Program Investment Charge Fund and the Alternative and Renewable Fuel and Vehicle Technology Fund—which reflects how unspent prior‑year appropriations are carried over into the current year.

- One‑Time General Fund Provided in 2017‑18. General Fund expenditures are proposed to decrease by a total of $587 million for natural resources and environmental protection departments. This is primarily attributable to one‑time funding provided in 2017‑18 related to (1) unanticipated firefighting expenditures for the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection ($469 million) and (2) one‑time spending by several departments to address the ongoing effects of the state’s recent drought ($66 million).

Figure 2

Environmental Protection Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Expenditures |

2016‑17 |

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

Change From 2017‑18 |

|

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Total |

$3,716 |

$6,364 |

$4,244 |

‑$2,120 |

‑33% |

|

By Department |

|||||

|

Resources Recycling and Recovery |

$1,500 |

$1,646 |

$1,542 |

‑$105 |

‑6% |

|

Air Resources Board |

700 |

1,730 |

1,208 |

‑522 |

‑30 |

|

State Water Resources Control Board |

1,137 |

2,578 |

1,069 |

‑1,509 |

‑59 |

|

Department of Toxic Substances Control |

247 |

263 |

279 |

16 |

6 |

|

Department of Pesticide Regulation |

96 |

104 |

104 |

— |

— |

|

Other departmentsb |

37 |

44 |

43 |

‑1 |

‑2 |

|

By Funding Source |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$96 |

$118 |

$84 |

‑$35 |

‑29% |

|

Special funds |

2,907 |

4,312 |

3,630 |

‑682 |

‑16 |

|

Bond funds |

427 |

1,564 |

161 |

‑1,403 |

‑90 |

|

Federal funds |

286 |

370 |

370 |

— |

— |

|

By Purpose |

|||||

|

State operations |

$1,249 |

$1,655 |

$1,588 |

‑$67 |

‑4% |

|

Local assistance |

2,467 |

4,555 |

2,656 |

‑1,899 |

‑42 |

|

Capital outlay |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

aIncludes Governor’s cap‑and‑trade spending plan, which was not included in the Governor’s budget. bIncludes the Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, and general obligation bond debt service. |

|||||

Budget Includes Some Significant Spending Increases. While overall spending is proposed to decline for resources and environmental protection departments in 2018‑19, the Governor’s budget includes a number of major proposals to increase spending and implement significant policy changes. We briefly describe several of these proposals in the box below. This report includes in‑depth reviews on each of these proposals.

Major Spending Proposals for Natural Resources and Environmental Protection

The Governor’s proposed budget for 2018‑19 includes several significant spending and policy proposals. These include the following:

Cap‑and‑Trade ($1.3 Billion). At the annual State of the State address, the Governor released a $1.3 billion spending plan for the use of discretionary cap‑and‑trade auction revenues in 2018‑19. It proposes to fund various programs, including ones to reduce local air pollution ($250 million); provide consumer rebates for low‑emission vehicles ($200 million); promote healthy forests ($160 million); and reduce emissions from trucks, buses, and equipment ($160 million).

Resources Bond ($1 Billion). The budget assumes that voters approve a bond—Chapter 852 of 2017 (SB 5, de León)—on the June 2018 ballot that would provide $4.1 billion for various natural resources‑related projects, such as to restore natural habitats, expand and rehabilitate state and local parks, and improve flood protection. The Governor’s 2018‑19 budget provides $989 million from this bond for 17 natural resources and environmental protection departments and conservancies, and an additional $31 million for the Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA).

Zero‑Emission Vehicle (ZEV) Infrastructure ($235 Million). The administration proposes to spend $235 million for the California Energy Commission—an increase of $199 million—in the budget year from various special funds to install electric vehicle chargers and hydrogen refueling stations throughout the state. This is intended to support the Governor’s goal of having 5 million ZEVs on California roads by 2030.

CalFire Helicopter Fleet Replacement ($98 Million). The budget includes General Fund support for the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire) to purchase four additional helicopters equipped to fight forest fires. The department has begun the process of replacing its aging helicopter fleet and currently plans to purchase its first new helicopter in 2018.

Parks and Recreation Program Expansion ($79 Million). Under Chapter 5 of 2017 (SB 1, Beall), the Department of Parks and Recreation will receive additional ongoing revenue from the increase in the state’s fuel taxes associated with off‑highway vehicles. As in the current year, a portion of this revenue will be used to address a historic shortfall in the State Parks and Recreation Fund and build a reserve ($34 million). In addition, the Governor’s 2018‑19 budget proposes to use $45 million in revenue towards facility improvements and program expansion, including adding 364 positions.

Oil and Gas Well Plug and Abandonment ($58 Million). The budget includes $58 million from the General Fund in 2018‑19 (and an additional $51 million over the two subsequent years) for the State Lands Commission to permanently secure offshore oil wells and related facilities at two sites in Southern California.

Fish and Wildlife Funding Augmentation ($51 Million). The Governor proposes to use $26 million from the Tire Recycling Management Fund, $18 million from the Motor Vehicle Account, and $7 million from the General Fund to (1) address a $20 million structural deficit in the Fish and Game Preservation Fund and (2) expand Department of Fish and Wildlife programs and activities, including improved management of marine fisheries and enhanced efforts to monitor and restore at‑risk species.

Conservation Corps Facility Expansion ($10 Million). The Governor’s budget plan proposes to expand the California Conservation Corps’ residential program over the coming years by building four new facilities. The budget includes $10 million from the General Fund for the acquisition and initial planning stages of these projects, which are estimated to cost a total of $185 million to complete.

Ventura Training Center ($7 Million). The budget provides a total of $7 million in 2018‑19 to CalFire and the California Conservation Corps (and an additional $2 million for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation) to create an 18‑month firefighting training and certification program for 80 parolees. This total includes $1 million for the preliminary plans phase of a $19 million project to complete facility improvements at the existing Ventura Conservation Camp.

Safe and Affordable Drinking Water ($5 Million). The Governor proposes to increase charges on fertilizer, dairies, caged animals, and drinking water customers in order to generate additional revenue to implement a new financial assistance program to provide clean drinking water targeted to disadvantaged communities. When fully implemented, these charges are expected to generate roughly $150 million annually. The Governor’s budget includes a transfer from the Underground Storage Tank Cleanup Fund to support startup activities by the State Water Resources Control Board ($3 million) and CDFA ($1 million).

Cross‑Cutting Issues

Cap‑and‑Trade

LAO Bottom Line. We recommend the Legislature ensure budget allocations for cap‑and‑trade auction revenues and related statutory direction align with the Legislature’s highest priorities. To help the Legislature evaluate the degree to which the Governor’s proposal achieves legislative goals, we recommend the Legislature direct the administration to provide certain information, including past outcomes and estimated future outcomes. We also recommend the Legislature consider alternative strategies to ensure fund solvency as more information about auction revenue becomes available over the next few months.

Background

State Law Establishes 2020 and 2030 GHG Limits. The Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006 (Chapter 488 [AB 32, Núñez/Pavley]) established the goal of limiting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions statewide to 1990 levels by 2020. Subsequently, Chapter 249 of 2016 (SB 32, Pavley) established an additional GHG target of reducing emissions by at least 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030. CARB is required to develop a Scoping Plan, which identifies the mix of policies that will be used to achieve the emission targets, and update the plan periodically.

AB 398 Extended Authority to Implement Cap‑and‑Trade From 2020 to 2030. One policy the state uses to help ensure it meets these GHG goals is cap‑and‑trade. Assembly Bill 32 authorized CARB to implement a market‑based mechanism, such as cap‑and‑trade, through 2020. Chapter 135 of 2017 (AB 398, E. Garcia) extended CARB’s authority to operate cap‑and‑trade from 2020 to 2030 and provided additional direction regarding certain design features of the post‑2020 program. We describe AB 398 changes and highlight key issues for legislative oversight in our December 2017 report Cap‑and‑Trade Extension: Issues for Legislative Oversight.

Cap‑and‑Trade Designed to Limit Emissions at Lowest Cost. The cap‑and‑trade regulation places a “cap” on aggregate GHG emissions from large GHG emitters, such as large industrial facilities, electricity generators and importers, and transportation fuel suppliers. Capped sources of emissions are responsible for roughly 80 percent of the state’s GHGs. To implement the program, CARB issues a limited number of allowances, and each allowance is essentially a permit to emit one ton of carbon dioxide equivalent. Entities can also “trade” (buy and sell on the open market) the allowances in order to obtain enough to cover their total emissions.

From a GHG emissions perspective, the primary advantage of a cap‑and‑trade regulation is that total GHG emissions from the capped sector do not exceed the number of allowances issued. Some entities must reduce their emissions if the total number of allowances available is less than the number of emissions that would otherwise occur. From an economic perspective, the primary advantage of a cap‑and‑trade program is that the market sets a price for GHG emissions, which creates a financial incentive for businesses and households to implement the least costly emission reduction activities. (For more details on how cap‑and‑trade works, see our February 2017 report The 2017‑18 Budget: Cap‑and‑Trade.)

Some Allowances Auctioned, Some Given Away for Free. About half of the allowances are allocated for free to certain industries, and most of the remaining allowances are sold by the state at quarterly auctions. Of the allowances given away for free, most are given to utilities and natural gas suppliers. CARB also allocates free allowances to certain energy‑intensive, trade‑exposed industries based on how much of their goods (not GHG emissions) they produce in California. This strategy is intended to minimize the extent to which emissions are shifted out of state because companies move their production of goods out of California in response to higher costs associated with the cap‑and‑trade regulation. The allowances offered at auctions are sold for a minimum price—set at $14.53 in 2018—which increases annually at 5 percent plus inflation.

State Revenue Generally Used to Facilitate GHG Reductions. The state collected about $6.5 billion in cap‑and‑trade auction revenue from 2012 through 2017. Money generated from the sale of allowances is deposited in the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF). Various statutes enacted over the last several years direct the use of auction revenue. For example, Chapter 807 of 2012 (AB 1532, Perez) requires auction revenues be used to further the purposes of AB 32. Under state law, revenues must be used to facilitate GHG emission reductions in California and, to the extent feasible, achieve other goals such as improving local air quality and lessening the effects of climate change on the state (also known as climate adaptation).

Current Law Allocates Over 60 Percent of Annual Revenue to Certain Programs. Under current law, annual revenue is continuously appropriated as follows: (1) 25 percent for the state’s high‑speed rail project, (2) 20 percent for affordable housing and sustainable communities grants (with at least half of this amount for affordable housing), (3) 10 percent for intercity rail capital projects, and (4) 5 percent for low carbon transit operations. In addition, AB 398 and subsequent budget legislation created the following ongoing GGRF allocations:

- Backfill Revenue Loss From Expanded Manufacturing Sales Tax Exemption. Assembly Bill 398 extended the sunset date from December 31, 2022 to July 1, 2030 for a partial sales tax exemption for certain types manufacturing and research and development equipment (hereafter referred to as the “manufacturing exemption”). It also expanded the manufacturing exemption to include equipment for other types of activities, such as certain electric power generation and agricultural processing, through July 1, 2030. The bill, as amended by subsequent budget legislation, also directs the Department of Finance (DOF) to annually transfer cap‑and‑trade revenue to the General Fund to backfill revenue losses associated with these changes.

- Intent to Backfill Revenue Loss From Suspension of State Fire Prevention Fee. Assembly Bill 398 suspended the state fire prevention fee from July 1, 2017 through 2030. The fee was previously imposed on landowners in State Responsibility Areas (SRAs), and the money was used to fund state fire prevention activities in these areas. The bill also expressed the Legislature’s intent to use cap‑and‑trade revenue to backfill the lost fee revenue and continue fire prevention activities. Subsequently, the 2017‑18 budget provided $80 million from the GGRF to backfill lost SRA fee revenue.

Past budgets have also allocated about $30 million ongoing to various agencies—primarily CARB—to administer GGRF funds and other air quality activities.

Governor’s Proposal

The administration released a summary of its cap‑and‑trade expenditure plan on January 26, 2018—roughly two weeks after the release of the Governor’s budget. Based on the information available at the time this report was completed, we describe the Governor’s proposal below.

$2.8 Billion Cap‑and‑Trade Expenditure Plan. As shown in Figure 3, the Governor proposes a $2.8 billion cap‑and‑trade expenditure plan for 2018‑19. This plan includes: (1) $1.4 billion in continuous appropriations, (2) $150 million in other existing spending commitments, and (3) $1.3 billion in new spending (also known as discretionary spending). The plan assumes $2.7 billion in auction revenue in 2017‑18 and $2.4 billion in 2018‑19. The $370 million difference between the proposed expenditures ($2.8 billion) and estimated revenue ($2.4 billion) in 2018‑19 would largely be paid from the projected fund balance at the end of 2017‑18.

Figure 3

Cap‑and‑Trade Expenditure Plan

(In Millions)

|

Program |

Department/Agency |

2017‑18 |

Proposed |

|

Continuous Appropriationsa |

$1,572 |

$1,369 |

|

|

High‑speed rail |

High‑Speed Rail Authority |

$655 |

$571 |

|

Affordable housing and sustainable communities |

Strategic Growth Council |

524 |

456 |

|

Transit and intercity rail capital |

Transportation Agency |

262 |

228 |

|

Transit operations |

Department of Transportation |

131 |

114 |

|

Other Existing Spending Commitments |

$153 |

$152 |

|

|

Manufacturing sales tax exemption backfill |

N/A |

$43 |

$89 |

|

Various administrative costs |

Various agencies |

30 |

35 |

|

SRA fee backfill |

CalFire/Conservation Corps |

80 |

28 |

|

Discretionary Spending |

$1,456 |

$1,250 |

|

|

Mobile Source Emissions |

|||

|

Local air district programs to reduce air pollution |

Air Resources Board |

$250 |

$250 |

|

Clean Vehicle Rebate Project |

Air Resources Board |

140 |

175 |

|

Freight and heavy‑duty vehicle incentives |

Air Resources Board |

320 |

160 |

|

Low‑income, light‑duty vehicles and school buses |

Air Resources Board |

100 |

100 |

|

Low‑carbon fuel production |

Energy Commission |

— |

25 |

|

Forestry |

|||

|

Forest health and fire prevention |

CalFire |

200 |

160 |

|

Local fire prevention grants |

Office of Emergency Services |

25 |

25 |

|

Urban forestry |

CalFire |

20 |

— |

|

Agriculture |

|||

|

Agricultural equipment |

Air Resources Board |

85 |

102 |

|

Methane reductions from dairies |

Food and Agriculture |

99 |

99 |

|

Incentives for food processors |

Energy Commission |

60 |

34 |

|

Healthy Soils |

Food and Agriculture |

— |

5 |

|

Agricultural renewable energy |

Energy Commission |

6 |

4 |

|

Other programs |

|||

|

Climate and energy research |

Office of Planning and Research |

11 |

35 |

|

Transformative Climate Communities |

Office of Planning and Research |

10 |

25 |

|

Waste diversion |

CalRecycle |

40 |

20 |

|

Integrated Climate Investment Program |

Go‑Biz |

— |

20 |

|

Energy Corps |

Conservation Corps |

— |

6 |

|

Technical assistance to community groups |

Air Resources Board |

5 |

5 |

|

Urban greening |

Natural Resources Agency |

26 |

— |

|

Natural lands climate adaptation |

Wildlife Conservation Board |

20 |

— |

|

Low income weatherization and solar |

Community Services and Development |

18 |

— |

|

Wetland restoration |

Department of Fish and Wildlife |

15 |

— |

|

Coastal climate adaptation |

Various agencies |

6 |

— |

|

Totals |

$3,181 |

$2,771 |

|

|

aContinuous appropriations based on Governor’s revenue estimates of $2.7 billion in 2017‑18 and $2.4 billion in 2018‑19. SRA = State Responsibility Area; CalFire = California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection; CalRecycle = California Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery; and Go‑Biz = Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development. |

|||

Similar to the current year, the administration takes certain allocations “off the top” before determining continuous appropriations. Specifically, the plan allocates $117 million to AB 398‑related actions—$28 million to backfill the SRA fee suspension and an estimated $89 million transfer to the General Fund to backfill the manufacturing exemption. (A $50 million fund balance in the SRA Fire Prevention Fund would cover the additional SRA costs on a one‑time basis.) The 60 percent total continuous appropriation percentages would be applied to about $2.3 billion—$2.4 billion in annual revenue minus $117 million for AB 398‑related actions.

Proposal Similar to 2017‑18 Spending Plan. As illustrated in Figure 3, the 2018‑19 proposal would fund many of the same programs that received funding in the 2017‑18 budget. The most significant differences in the 2018‑19 proposal include:

- Less Funding for Freight and Heavy‑Duty Vehicle Incentives. The proposal includes $160 million for freight and heavy‑duty vehicles, or half of what was provided in 2017‑18. This represents the largest year‑over‑year decrease in funding for any program.

- Provides $20 Million for Integrated Climate Investment Program. The plan provides $20 million to the Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development for the Integrated Climate Investment Program, which will provide funding through the existing California Lending for Energy and Environmental Needs Center. This program provides financing for private sector infrastructure projects intended to reduce GHG emission and improve climate resilience, such as energy efficiency and water conservation. The administration also intends to explore ways to develop new financing mechanisms for similar types of projects.

- Expands and Modifies Climate Change and Energy Research Program. The proposal includes $35 million for the Office of Planning and Research to provide grants for research and development of innovative GHG reduction and climate adaptation technologies. This amount is $24 million more than was provided in 2017‑18. In addition, the administration intends to focus on technologies that are in earlier stages of research and development.

- Backfills Certain Special Funds That Are Used for Other Activities. The plan includes $25 million for CEC to support low‑carbon fuel production, which is currently funded through the Alternative and Renewable Fuel Vehicle Technology Fund (ARFVTF). It also provides $26 million to CARB for the Carl Moyer Program (included as part of the grants for local air pollution reductions), which is currently funded through the Air Pollution Control Fund (APCF). These allocations do not reflect a net change in spending for these activities. Instead, they backfill the special funds that previously supported these activities because the administration proposes to redirect these special funds to other purposes. Specifically, the administration proposes to redirect ARFVTF resources to fund additional ZEV infrastructure and APCF resources to address the structural shortfall in the Fish and Game Preservation Fund. (We discuss each of these proposals elsewhere in this report.)

Includes $232 Million in New Multiyear Funding Commitments. Most of the proposed discretionary expenditures are one time, but some programs would receive multiyear funding. These multiyear programs are: (1) $200 million annually over eight years to continue light‑duty ZEV rebates, including $175 million for the Clean Vehicle Rebate Project and $25 million for incentives for light‑duty vehicles for low‑income consumers; (2) about $26 million for the Carl Moyer Program backfill through at least 2023; and (3) $6 million annually to the California Conservation Corps (CCC) to continue energy efficiency activities in the Energy Corps program. The Proposition 39 (2012) revenue transfers to the CCC for the Energy Corps program expire in 2017‑18.

Governor’s Plan Spends Almost All of Estimated Available Funds. The Governor’s plan spends nearly all of the funds it estimates will be available through 2018‑19, leaving a fund balance of about $20 million at the end of the budget year. To address the risk that actual revenue is lower than estimated and ensure fund solvency, the administration proposes budget bill language that gives DOF authority to proportionally reduce most 2018‑19 discretionary allocations if auction revenues are not sufficient. The proposal also specifies that DOF could not reduce allocations to programs administered by CARB, healthy forests, and the Energy Corps program.

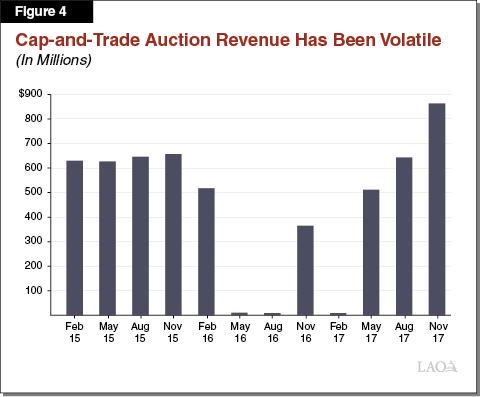

LAO Assessment: Revenue Projections

Auction Revenue Has Been Volatile, but Recent Actions Likely Increase Stability. Figure 4 shows the volatility in quarterly auction revenue over the last couple of years since fuel suppliers were required to obtain allowances in 2015. Notably, there was a substantial decrease in revenue collected in a few auctions in 2016 and early 2017. This decrease in revenue was primarily due to a decrease in the number of allowances purchased at auctions, rather than a significant decrease in prices. Several factors likely contributed to this decrease in the number of allowances purchased, including (1) an oversupply of allowances in the market because emissions were below the cap, (2) uncertainty related to a court case challenging the legality of state‑auctioned allowances, and (3) uncertainty about CARB’s legal authority to continue cap‑and‑trade beyond 2020.

Two of the factors contributing to the low revenue were addressed last year. First, an appeals court ruled that the auctions were legal, and the state Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal of that ruling. Second, the Legislature passed AB 398, extending CARB’s legal authority to continue cap‑and‑trade through 2030. Both actions provided greater legal certainty about the future of the program, which tends to increase demand for allowances. As a result, although there continues to be revenue uncertainty and potential for volatility (discussed below), it is unlikely that the state will have consecutive auctions with little or no revenue over the next few years.

Governor’s Revenue Estimates Slightly Lower Than Ours, but Still Reasonable. The administration’s revenue estimates—$2.7 billion in 2017‑18 and $2.4 billion in 2018‑19—are slightly lower than what we consider to be most likely, but still within a reasonable range. We estimate annual state revenue from auctions will be about $3 billion in both 2017‑18 and 2018‑19. The first two auctions in 2017‑18 generated a total of $1.5 billion. At these auctions, all allowances were sold at prices above the minimum price. Our revenue estimates assume all allowances continue to sell and allowance prices remain slightly above the minimum price through 2018‑19.

There are, however, a wide variety of factors—both long and short term—that contribute to significant revenue uncertainty, which could be higher or lower than projected. Over the next decade, economic conditions and technological advancements will have major effects on market prices. In the next couple of years, additional factors contributing to uncertainty include:

- Allowance Banking. Demand for allowances and prices will depend on the extent to which entities purchase allowances at auctions with the intention of holding onto them for future years when prices are higher (also known as banking). The amount of banking will depend on factors such as market expectations about future price increases. The ultimate effects of different levels of banking on state revenue are unclear. For example, less banking would reduce demand and prices for allowances in the short term, but could increase future prices.

- Return of Allowances That Were Unsold in Previous Auctions. Allowances that go unsold at auctions are reoffered (in limited amounts) once prices exceed the minimum price for two consecutive auctions. For example, the November 2017 auction included the sale of over 13 million state allowances that previously went unsold in 2016. If auction prices remain above the floor (as our revenue estimates assume), a similar amount of previously unsold allowances will continue to be offered in the next several auctions. However, if auction prices drop to the floor, the number of allowances offered over the next several auctions will decrease. Consequently, small differences in auction prices could affect short‑term revenue by hundreds of millions of dollars because of the difference in the number of allowances auctioned.

- Future CARB Regulatory Changes. Assembly Bill 398 directed CARB to make, or at least consider, a variety of changes to the cap‑and‑trade program, including potential changes to banking rules and the post‑2020 supply of allowances. Over the next year or so, CARB will be implementing these changes. These implementation decisions could have significant effects on allowance prices and auction revenue.

LAO Assessment: Short‑ and Long‑Term Spending Priorities

Proposal to Ensure Fund Solvency Prioritizes Certain Programs. Given the revenue uncertainty and the small projected fund balance at the end of 2018‑19, there is a risk that the proposal would allocate more than the available funding if revenues are lower than the administration’s estimates. As discussed above, if auction revenues are not sufficient to cover program costs, the Governor’s plan would give DOF authority to proportionally reduce allocations for all discretionary programs except programs administered by CARB, healthy forests, and the Energy Corps program. Moreover, this effectively prioritizes funding for these programs over other discretionary programs if revenue is lower than expected. The Legislature will want to ensure that any such prioritization is consistent with its priorities.

Plan Increases Long‑Term Spending Commitments. The Governor’s proposal includes $232 million in new multiyear spending commitments. The Legislature will want to ensure any long‑term spending commitments are consistent with its long‑term priorities. Figure 5 shows the total spending commitments beyond the 2018‑19 budget (out‑year spending) included in the administration’s proposal, assuming $2.4 billion in annual revenue. Under this scenario, about $1.8 billion (over 70 percent) of annual revenue would be committed in future years, largely for the continuous appropriations, commitments related to AB 398, and rebates for ZEVs. This would leave roughly $600 million (less than 30 percent) for other program expenditures. We also note that this scenario assumes the Legislature does not make any additional out‑year funding commitments in the budget.

Figure 5

Plan Increases Out‑Year Spending Commitments

(In Millions)

|

Program |

Annual |

Time Period |

|

Continuous Appropriationsa |

$1,339 |

Ongoing |

|

Other Existing Commitments |

199 |

|

|

SRA fee backfill |

80 |

Through 2030 |

|

Manufacturing sales tax exemption backfill |

89b |

Through 2029‑30 |

|

Various administrative costs |

30 |

Through 2030 |

|

New Commitments |

232 |

|

|

Clean Vehicle Rebate Project and other ZEV rebates |

200 |

Through 2025‑26 |

|

Carl Moyer Program backfill |

26 |

Through 2023c |

|

Energy Corps |

6 |

Through 2030 |

|

Total |

$1,770 |

|

|

aAssumes $2.4 billion in annual revenue. bAssumes amount of future transfers consistent with Governor’s 2018‑19 estimate. Under current law, amount increases to low hundreds of millions of dollars in 2023. cUnder current law, the revenue for this program expires at the end of 2023. SRA = State Responsibility Area and ZEV = zero‑emission vehicle. |

||

LAO Assessment: Allocation Issues to Consider

As the Legislature considers how to spend GGRF revenues, it is important to keep in mind that the primary goal of a cap‑and‑trade program is to provide an economy‑wide incentive for businesses and consumers to undertake cost‑effective emission reductions. This is accomplished through establishing a price on emissions, not spending auction revenue. From an economic perspective, auction revenues are often thought of as a by‑product of cap‑and‑trade programs, not the goal of the program. Furthermore, spending all auction revenue on GHG reductions is likely not necessary to meet the state’s GHG goals and likely increases the overall costs of emission reduction activities. This is because, if the cap is effectively limiting emissions, spending on GHG reductions from major sources of emissions interacts with the cap‑and‑trade regulation in a way that changes the types of emission reduction activities undertaken, but not the overall level of emission reductions. In most cases, the different mix of reductions would be more costly overall. (For more details, see our 2016 report Cap‑and‑Trade Revenue: Strategies to Promote Legislative Priorities.)

Below, we discuss several issues for the Legislature to consider when determining how to allocate cap‑and‑trade expenditures.

Structure of Spending Plan Largely Depends on Legislative Priorities. The Legislature will want to consider how it could allocate revenue to achieve its highest priorities within current statutory and constitutional limitations. To the extent that the Legislature continues to focus spending on programs primarily aimed at GHG reduction activities, spending options should be evaluated in the context of how they interact with the cap‑and‑trade regulation, as discussed above. Potential spending strategies could include:

- Reductions Outside of Cap. The Legislature could target funds to achieve GHG reductions from uncapped sources. The Governor’s plan includes several components that would provide funding for GHG reductions outside of the cap, including about $100 million for methane emission reductions from dairies and $160 million for forest health activities. The Legislature could provide more funding to these or other programs that target uncapped emissions.

- Targeting Other Market Failures Not Addressed by Cap‑and‑Trade. The Legislature could use funds to address other “market failures” that the cap‑and‑trade regulation does not address. For example, cap‑and‑trade might not provide adequate incentive in the private sector for research and development activities on GHG‑reducing technologies because the benefits of such activities can “spill over” to other companies that can profit by implementing developments made by others in their own products. As a result, private companies do not always invest in research and development activities at a level that is socially optimal. Thus, there could be a rationale for providing some additional state funding in this area. The budget includes $35 million for a modified research and development program intended to address these issues.

When evaluating programs that are primarily intended to reduce GHGs, the Legislature will also want to consider the degree to which these programs are likely to encourage reductions in other jurisdictions. This could be done by either encouraging technological advancements that help reduce GHGs or demonstrating cost‑effective climate policies that can be adopted elsewhere.

The Legislature might also want to consider how the funds could be used to achieve other high‑priority policy goals related to climate change. For example, climate adaptation is identified as a priority under current law. The Legislature could consider allocating a greater share of funding to activities intended to help the state manage the effects of climate change. The Governor’s plan includes some funding intended to manage the effects of climate change as well as reduce GHGs, including $185 million for forest management and fire prevention. Similarly, current law identifies the reduction of local air pollution as a priority. As such, the Legislature could consider providing a greater share of funding to programs intended to accomplish this goal. The Governor’s plan includes $160 million for freight and heavy‑duty vehicle incentives and $250 million for local air district programs to reduce local air pollution. These programs are targeted at some of the most harmful local air pollutants, such as diesel particulate matter from heavy‑duty engines.

Key Questions to Consider When Evaluating Different Programs. After the Legislature identifies its highest priorities, it will want to identify which programs are likely to achieve those goals effectively and how those programs should be structured. To help accomplish this, the administration is required to release an annual March report with estimated GHG reductions from programs that have been funded to date. It can be difficult to accurately estimate emission reductions from each program, and the amount and accuracy of information provided in past March reports has been limited. We discuss some of these limitations in our April 2016 web post Administration’s Cap‑and‑Trade Report Provides New Information, Raises Issues for Consideration. The administration has recently undertaken efforts to improve its estimates of program outcomes, such as by adding estimates of co‑benefits. However, these estimates were not included in the 2017 report. To the extent more complete and reliable estimates are included in the upcoming March report, it could enhance the quality of information available to make legislative spending decisions.

Given the later release of the cap‑and‑trade spending plan and some of the associated details, our office has had a limited amount of time to review all of the proposals. However, some of the key questions that we think the Legislature should consider as it reviews the plan include:

- Questions on Expected Outcomes. What outcomes is each program expected to accomplish? To what extent can each program be expected to reduce GHG emissions and meet other legislative goals, such as local air pollution reductions? How cost‑effective are the proposed options at meeting these objectives?

- Questions for Programs That Received Funding in Past Years. What outcomes has the program accomplished so far? Are there enough cost‑effective projects remaining to justify continuing expenditures? For example, the budget proposes $99 million to reduce methane emissions from dairies, which would bring the total amount provided in recent years to $260 million. Are there enough cost‑effective methane reduction projects remaining that these funds could support in 2018‑19?

- Questions for New Programs. How will projects be selected? Are criteria for selecting projects consistent with legislative priorities? For example, how will the most valuable research and development projects be identified in the climate research program?

Current Statutory Direction Might Not Align With Some Program Goals. The current GGRF statutory direction, guidance, and reporting requirements largely prioritize GHG reductions. This could be a problem if the primary goal for some of the programs is something other than GHG reductions. If statutory direction is not aligned with the primary goals of the program, the programs are less likely to be structured in a way that achieve the Legislature’s goals most effectively. For example, if the primary goal of a program is to achieve local air pollutant reductions, but the statutory direction emphasizes GHG reductions, it is possible the program will be implemented in ways that do not achieve the greatest amount of local air pollutant reductions possible.

Recommendations

Ensure Allocations and Legislative Direction Are Consistent With Legislative Priorities. We recommend the Legislature allocate funds to programs that are likely to achieve its highest priority policy goals, which could include GHG reductions, as well as such things as local air pollution reductions and/or climate adaptation. The Legislature will also want to ensure the statutory direction for GGRF spending aligns with the primary policy goals of each program. This would help ensure that departments structure programs and prioritize projects that help achieve the Legislature’s goals most effectively.

Direct Administration to Report on Key Program Information. We recommend the Legislature direct the administration to report at budget hearings on a variety of issues, including (1) the expected outcomes associated with each program that would receive funding in the budget, such as estimated overall costs and benefits; (2) the outcomes that existing programs have accomplished so far; and (3) how new programs will be structured, including the process and criteria that will be used to select projects. This information would help the Legislature evaluate the extent to which the plan achieves its goals effectively.

Consider Options to Ensure Solvency as Additional Revenue Information Becomes Available. We recommend the Legislature re‑evaluate the overall amount of cap‑and‑trade allocations over the next few months as more information about auction revenue becomes available. Although 2018‑19 revenue will continue to be subject to uncertainty, the Legislature will have additional information about 2017‑18 revenue and it could adjust its spending plan accordingly. If revenue expectations at that time are consistent with the Governor’s estimates (or lower), the spending plan would leave almost no fund balance at the end of 2018‑19. In this scenario, the Legislature might want to consider options to mitigate against downside revenue risk. For example, the Legislature could allocate less money in 2018‑19. Alternatively, it could adopt an approach similar to the one proposed by the administration, which designates that certain programs are guaranteed funding, and the amount provided to the remaining programs would depend on whether sufficient revenue is collected. If the Legislature adopts this strategy, it will want to ensure that guaranteed funding goes to programs that are the highest legislative priorities.

Implementation of Natural Resources Bond (SB 5)

LAO Bottom Line. The administration’s 2018‑19 budget plan includes $1 billion in appropriations for a number of departments to begin implementing SB 5, a resources‑related bond measure—Proposition 68—that will be on the June 2018 statewide ballot. Overall, we find the administration’s spending plan to be reasonable. However, we recommend two modifications: (1) specifying in budget bill language which flood management projects the Department of Water Resources (DWR) intends to undertake and (2) utilizing Proposition 1 funding in place of SB 5 funding for two Department of Fish and Wildlife (DFW) programs. In addition, we recommend that the administration report at budget hearings on its longer‑term plan to allocate SB 5 funds. Finally, we recommend that the Legislature consider developing an alternative funding plan for high‑priority projects and programs in the event that SB 5 should not be approved by voters.

Background

Legislature Placed $4.1 Billion Bond Measure on June 2018 Ballot. In the fall of 2017, the Legislature passed and the Governor signed SB 5 (Chapter 852, de León). This bill places a natural resources‑related bond—Proposition 68—on the June 2018 statewide ballot. If approved by voters, the bond measure would authorize the state to sell a total of $4.1 billion in general obligation bonds for specified purposes, which are summarized in Figure 6. (This total includes $4 billion in new bonds and a redirection of $100 million in unsold bonds that voters previously approved for specific natural resources uses.)

Figure 6

Uses of Proposition 68 Bond Funds

(In Millions)

|

Natural Resource Conservation and Resiliency |

$1,547 |

|

State conservancies and wildlife conservation |

767 |

|

Climate preparedness and habitat resiliency |

443 |

|

Ocean and coastal protection |

175 |

|

River and waterway improvements |

162 |

|

Parks and Recreation |

$1,283 |

|

Parks in neighborhoods with few parks |

725 |

|

Local and regional parks |

285 |

|

State park restoration, preservation, and protection |

218 |

|

Trails, greenways, and rural recreation |

55 |

|

Water |

$1,270 |

|

Flood protection |

550 |

|

Groundwater recharge and cleanup |

370 |

|

Safe drinking water |

250 |

|

Water recycling |

100 |

|

Total |

$4,100 |

SB 5 Includes Various Administrative Provisions. The bond measure includes a number of requirements designed to control how these funds are administered and overseen by state agencies. The measure requires regular reporting of how the bond funds have been spent, as well as authorizes financial audits by state oversight agencies. The measure also limits to 5 percent how much of the funding can be used for state administrative costs. The measure also includes several provisions designed to assist “disadvantaged communities” (with median incomes less than 80 percent of the statewide average) and “severely disadvantaged communities” (with median incomes less than 60 percent of the statewide average). For example, it requires that for each use specified in the bond, at least 15 percent of the funds be spent to assist severely disadvantaged communities.

Governor’s Proposal

Budget Includes $1 Billion From SB 5. The administration proposes to appropriate about one‑quarter of the bond in the budget year. Specifically, this includes $989 million for 17 natural resources and environmental protection departments and $31 million for the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA). Figure 7 shows expenditures for each department and program proposed for SB 5 funding in 2018‑19. (The administration states that it would request removal of the budget appropriations in the event that voters do not approve Proposition 68.)

Figure 7

SB 5 Spending by Department

(In Millions)

|

Department and Purpose |

2018‑19 Amount |

|||

|

Local Assistance |

Capital Outlay |

State Operations |

Total |

|

|

Parks and Recreation |

$460.3 |

— |

$7.3 |

$467.6 |

|

Parks in neighborhoods with few parks |

460.3 |

— |

3.1 |

463.4 |

|

State park maintenance planning and restoration |

— |

— |

4.2 |

4.2 |

|

Water Resources |

$46.3 |

$117.9 |

$26.6 |

$190.8 |

|

Flood protection |

— |

94.0 |

4.5 |

98.5 |

|

Groundwater recharge |

46.3 |

— |

15.5 |

61.8 |

|

Salton Sea restoration |

— |

23.9 |

6.1 |

30.0 |

|

Urban streams restoration |

— |

— |

0.5 |

0.5 |

|

Water Resources Control Board |

$145.9 |

— |

$1.3 |

$147.3 |

|

Groundwater recharge and cleanup |

83.7 |

— |

0.3 |

84.0 |

|

Safe drinking water |

62.3 |

— |

1.0 |

63.3 |

|

Natural Resources Agency |

$56.5 |

— |

$0.7 |

$57.2 |

|

River recreation and parkways |

38.0 |

— |

0.6 |

38.6 |

|

Multibenefit green infrastructure |

18.5 |

— |

0.1 |

18.6 |

|

Food and Agriculture |

$29.6 |

— |

$1.4 |

$31.0 |

|

Water efficiency and enhancement |

17.8 |

— |

0.6 |

18.4 |

|

Healthy soils |

8.6 |

— |

0.4 |

9.1 |

|

Deferred maintenance at fairgrounds |

3.2 |

— |

0.4 |

3.6 |

|

Various conservanciesa |

$23.9 |

$3.2 |

$2.1 |

$29.2 |

|

River and waterway improvements |

16.6 |

— |

0.7 |

17.4 |

|

Wildlife conservation and habitat resiliency |

7.3 |

3.2 |

1.3 |

11.8 |

|

Fish and Wildlife |

$22.1 |

— |

$1.6 |

$23.6 |

|

River and wetland restoration |

22.1 |

— |

1.6 |

23.6 |

|

Wildlife Conservation Board |

$20.0 |

— |

$0.9 |

$20.9 |

|

Habitat restoration |

18.0 |

— |

0.8 |

18.8 |

|

Lower American River restoration |

2.0 |

— |

— |

2.0 |

|

Ocean Protection Council |

$20.0 |

— |

$0.3 |

$20.3 |

|

Marine wildlife and coastal ecosystems |

10.0 |

— |

0.1 |

10.2 |

|

Assist coastal communities |

10.0 |

— |

0.1 |

10.1 |

|

Forestry and Fire Protection |

$13.6 |

— |

$1.1 |

$14.6 |

|

Urban forestry |

13.6 |

— |

1.1 |

14.6 |

|

Coastal Conservancy |

$4.9 |

— |

$0.2 |

$5.1 |

|

San Francisco Bay restoration |

4.9 |

— |

0.1 |

5.0 |

|

Coastal forests |

— |

— |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

Conservation Corps |

$4.6 |

— |

$5.2 |

$9.8 |

|

Parkway restoration |

0.0 |

— |

4.9 |

4.9 |

|

Grants to local corps programs |

4.6 |

— |

0.3 |

4.9 |

|

Conservation |

$1.0 |

— |

$0.2 |

$1.2 |

|

Agricultural conservation |

1.0 |

— |

0.2 |

1.2 |

|

Statewide bond administration |

— |

— |

$1.4 |

$1.4 |

|

Totals |

$848.5 |

$121.1 |

$50.2 |

$1,019.8 |

|

aBaldwin Hills, Sacramento‑San Joaquin Delta, San Diego River, San Gabriel Mountains and Los Angeles River, Santa Monica Mountains, Sierra Nevada, and Tahoe Conservancies. |

||||

Primarily Funds New Projects, but Also Some Administrative Costs. More than $8 out of every $10 proposed in 2018‑19 would be for local assistance—typically allocated through a competitive grant process to local governments, nonprofits, and other organizations to implement projects. In addition, $121 million is for state capital outlay projects, including $94 million for flood protection projects and $30 million for the restoration of the Salton Sea. Less than 5 percent of the proposed funding is for state operations, which includes administrative support, planning activities, and some project work to be implemented by state agencies, such as a redwood reforestation project at Redwood National and State Parks on the northern coast of the state. As shown in Figure 8 the administration’s spending plan would include 79.5 new positions to implement SB 5 (including 9 positions at CDFA).

Figure 8

SB 5 Positions Requested

2018‑19

|

Department |

Positions |

|

Parks and Recreation |

21.0 |

|

Water Resources Control Board |

10.0 |

|

Food and Agriculture |

9.0 |

|

Conservation Corps |

7.0 |

|

Water Resources |

7.0 |

|

Natural Resources Agency |

7.0 |

|

Wildlife Conservation Board |

5.0 |

|

Forestry and Fire Protectiony |

4.0 |

|

Sierra Nevada Conservancy |

3.0 |

|

Ocean Protection Council |

2.0 |

|

Sacramento‑San Joaquin Delta Conservancy |

2.0 |

|

Coastal Conservancy |

1.5 |

|

San Diego River Conservancy |

1.0 |

|

Total |

79.5 |

LAO Assessment

Reasonable Approach to Implementing First Year of Funding. Overall, we find that the administration’s SB 5 funding plan for 2018‑19 is reasonable. While departments are proposing to spend hundreds of millions of dollars in the budget year, they generally have targeted this spending towards programs that are likely to be successfully implemented this first year. This includes focusing on grant programs for which administering departments are confident that they can develop grant guidelines and make awards before the end of the budget year, such as when the funding supports existing or recently active grant programs. In addition, some spending is targeted towards more narrowly defined state purposes, such as implementing the Salton Sea Management Plan. For new programs authorized by the bond, the administration generally is requesting funding for administrative positions that would be responsible for developing program guidelines during the budget year.

We also note that in most cases, local assistance and capital outlay funding is targeted to programs where prior bond funds largely have already been spent or committed to projects, leaving little available for new projects absent this proposal. For example, the proposal would provide $47 million for DWR to offer another round of grants to local groundwater agencies that are in the process of developing plans to help implement the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA). Proposition 1 (2014) provided such support to some agencies; however, those grants have been fully allocated and not every local agency received funding.

Notably, there are a number of programs in SB 5 for which the administration is not requesting any resources for 2018‑19, including for projects or administrative support. This includes some programs with relatively large amounts of funding authorized in SB 5, such as for multibenefit projects to implement voluntary agreements that improve stream conditions for fish ($200 million), water recycling projects ($80 million), and coastal watersheds restoration ($64 million). Based on our review, however, the administration has a reasonable rationale for delaying spending on these programs. In some cases, it could be premature to appropriate spending in the budget year because program details and planning will need more time to be developed (such as for the voluntary agreements), and in other cases previously approved funds remain available (such as water recycling funds in Proposition 1).

Long‑Term Funding Plan Not Identified. While the budget‑year plan appears reasonable, the administration has not identified a spending plan for subsequent years. Therefore, it is unclear when the administration expects to begin funding programs that are not proposed to receive project funding in the budget year. It is also unclear how many years the administration thinks it will take to fully appropriate all of the funds.

Additional Scrutiny Needed for Some Proposals. Though the budget‑year proposals generally seem reasonable, we have identified a couple proposals that raise specific concerns. These proposals include:

- DWR Flood Control Projects. The administration proposes $94 million for flood control projects. However, the proposal by DWR does not specify which projects will be funded, denying the Legislature the ability to provide sufficient oversight over how these funds will be spent. The state’s flood management infrastructure has billions of dollars of needed renovations and improvements according to various reports, and it is unclear which of those needs will be targeted by the proposed funding.

- DFW Competitive Grant Programs. The budget plan proposes a total of $14 million for two grant programs related to habitat restoration and improving conditions for fish and wildlife. However, the proposed budget already includes $28 million from Proposition 1 for similar DFW activities, and there remains $179 million in authority from that bond that has not yet been committed for these types of projects. At the time of this analysis, the department was unable to explain why the SB 5 funding plan included appropriations for these programs when there was still outstanding funds available from another bond.

High‑Priority Projects Might Lack Funding if Voters Reject SB 5. The Legislature will not know until close to its constitutional deadline to pass the state budget whether voters have approved SB 5. Despite this uncertainty, we think it is appropriate that the Governor has included these proposals in his January budget because doing so allows the Legislature several months to review the proposals and ensure that the spending plan is consistent with its priorities. However, should the bond measure fail to pass, the Legislature might be faced with decisions about whether it wants to find alternative funding sources for certain programs with little time before the constitutional budget deadline to explore its options. Considering potential alternative funding sources might be especially important for programs where (1) the state has an obligation to provide funds (such as for the Salton Sea Management Plan), (2) the state could face long‑term financial costs if it does not make certain investments (such as in the case of maintaining flood management or other infrastructure), or (3) additional funding might be key to successful execution of a statewide priority (such as support for local implementation of SGMA). Some existing programs might be able to utilize past funding sources. For example, the Urban Forestry Program is supported in the current year with GGRF. Other programs, however, rely on nearly exhausted bond funds and would need a new fund source to continue.

LAO Recommendations

Approve Proposals With a Couple Modifications. We recommend approval of most of the administration’s SB 5 funding requests and associated positions. However, based on our review of the proposals, we recommend the following two modifications:

- Budget Bill Language Specifying Flood Projects. We recommend that the Legislature direct DWR to report at budget hearings on which specific flood management projects will be funded in the budget year. Based on this information—as well as an assessment of its own priorities—we recommend that the Legislature adopt budget bill language that would schedule the proposed flood funding by project.

- Replace SB 5 Funds With Proposition 1 Funding for Two DFW Grant Programs. We recommend reducing DFW’s allocation from SB 5 by $14 million and increasing its appropriation from Proposition 1 by an equivalent amount. This will be more consistent with the administration’s broader approach to allocating the first year of SB 5 funding. Moreover, it will be administratively more efficient for the department to operate one set of bond programs related to habitat restoration and improving conditions for fish and wildlife, rather than simultaneously administering parallel programs from different bonds.

Report at Budget Hearings on Long‑Term Funding Plan. We recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to report at budget hearings on its longer‑term strategy for expending SB 5 funds. Doing so would give the Legislature a better sense of when programs not proposed for funding in 2018‑19 would be implemented and how long the administration proposes taking to fully allocate bond funding.

Consider Budget‑Year Priorities and Alternative Funding if SB 5 Fails. The Legislature might wish to consider whether there are certain programs funded in SB 5 that would be high enough priorities to fund from other sources should SB 5 fail. This could involve, for example, the budget subcommittees identifying an alternative budget approach for specific programs—including funding amounts and sources—that could be adopted in June if the proposition fails. Aside from the General Fund, whether an alternative fund source could be used for a particular program would probably depend on the allowable uses of that fund. In addition, the use of alternative fund sources generally would involve the trade‑off of not having those funds available for other purposes.

Ventura Training Center

LAO Bottom Line. We recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal to convert the existing Ventura conservation camp for inmates into a new Ventura Training Center that would provide a firefighter training and certification program for parolees. We find that the proposed program is unlikely to be the most cost‑effective approach to reduce recidivism. To the extent that reducing recidivism is a high priority for the Legislature, it could redirect some or all of the proposed funding to support evidence‑based rehabilitative programming for offenders in prison and when they are released from prison. Similarly, the Legislature could explore if other options are available to provide CCC corpsmembers training opportunities, to the extent it is interested in doing so.

Background

Offender Rehabilitation Programs Intended to Reduce Recidivism. Research has shown that certain criminal risk factors are particularly significant in influencing whether or not individuals commit new crimes following their release from prison (known as recidivating). For example, individuals who have low performance, involvement, and satisfaction with school and/or work are more likely to recidivate than individuals who do not exhibit these characteristics. Research also shows that rehabilitation programs (such as substance use disorder treatment and employment preparation) can be designed to address specific criminal risk factors. For example, employment counseling programs can help reduce or eliminate the criminal risk resulting from an offender’s low involvement in work. In addition, research suggests that programs are most effective in reducing recidivism when they are targeted at individuals who have a high risk of recidivating due to factors that could be addressed with rehabilitation programs. (For more information on the key criminal risk factors and principles for reducing recidivism, please see our recent report Improving In‑Prison Rehabilitation Programs.)

State Provides Various Rehabilitation Programs to Parolees. Prior to an inmate’s release from prison, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) generally uses assessments to determine how likely the inmate is to recidivate as well as what criminal risk factors he or she has. The department uses this information to target many of its rehabilitation programs once the inmate is released and supervised by state parole agents in the community. The 2017‑18 budget included $215 million to support various parolee rehabilitation programs. One such program is the Specialized Treatment for Optimized Programming (STOP), which provides a range of services, such as substance use disorder treatment, anger management training, and employment services to parolees. To be eligible for STOP, parolees must have a moderate to high risk of reoffending and be identified as having a criminal risk factor that can be addressed by services available through the program.

Multiple Agencies Have Professional Firefighter Crews. The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire) employs over 7,000 firefighters each year during fire season. Of those, about 1,700 are seasonal firefighters, classified as “Firefighter I,” CalFire’s entry‑level firefighter classification. A Firefighter I is a temporary employee who is hired only for the duration of the “fire season”—the period of time when fires are most likely to occur at the greatest intensity. Individuals are usually hired in April, May, or June—as CalFire increases staffing for the fire season—and work for up to nine months, depending on the duration and intensity of the season. More experienced firefighters can apply to become a Firefighter II—a permanent employee. Both types of firefighters typically staff “engine crews,” which are made up of a fire engine and three to four firefighters, as well as an engine operator.

Federal and local agencies also operate fire crews. Some larger local agencies, such as the Los Angeles County Fire Department, provide their own wildfire protection. However, many agencies mostly respond to structure fires rather than wildfires. In addition, the U.S. Forest Service employs roughly 10,000 firefighters for fire protection in national forests.