LAO Contact

March 20, 2020

Collective Bargaining: Assessing Proposed Employee Compensation Increases

The Legislature likely will be asked to approve labor agreements for eight bargaining units in 2020—the employees represented by these bargaining units account for more than one-half of the state’s General Fund personnel costs. The purpose of this post is to highlight the importance of requiring the administration to justify compensation increases it agrees to in labor agreements submitted to the Legislature for approval. In particular, we discuss the importance of compensation studies to provide such justification. Labor agreements establish the state’s compensation policies and essentially lock the state into a level of spending for the future. Especially in the case of labor agreements that are in effect for multiple years, these provisions limit the Legislature’s flexibility to respond to evolving economic conditions. There currently is significant economic uncertainty with unknown effects on the state’s budget in both the short and long term. Accordingly, although we think the administration should justify compensation increases in any economic condition, it is particularly important now.

Background

Legislature’s Role in Establishing Rank-and-File State Employee Compensation

Legislative and Employee Ratification of Labor Agreements Is Final Step in Collective Bargaining Process. Compensation for rank-and-file state employees—constituting about 80 percent of the state workforce—is established through the collective bargaining process under the Ralph C. Dills Act (Dills Act). The Governor is the state employer for purposes of bargaining although some rank-and-file employees work for another elected constitutional officer. At the bargaining table, the Governor is represented by the California Department of Human Resources (CalHR). Employees are organized into 21 bargaining units that are represented by unions at the bargaining table. After CalHR and a union agree to terms and conditions of employment, the administration submits to our office the resulting labor agreement—referred to as a memorandum of understanding, or MOU—and the administration’s estimated costs of the agreement. Our office has ten calendar days after receiving the MOU to issue a fiscal analysis to the Legislature. Pursuant to Section 19829.5 of the Government Code, the MOU shall not be subject to legislative determination until either our office has released its analysis or ten calendar days have elapsed. During its ratification vote, the Legislature votes to approve or reject the entirety of the MOU. An MOU does not go into effect unless it is ratified by both the Legislature and affected state employees.

Legislature Considers Changes to State Employee Compensation in Annual Budget. Under the Dills Act, any provision of an MOU that requires the expenditure of funds generally may not become effective unless approved by the Legislature in the annual budget act. This means that the Legislature may choose not to fund fully a provision included in a ratified MOU (alternatively, the Legislature may choose to appropriate more money than is required by an MOU—for example, approving in the budget a higher level of salary than established in an MOU). If the Legislature does not fully fund a provision of a ratified MOU, either the Governor or the union may reopen negotiations on all or part of the agreement.

Compensation Study

Before Submitting New Labor Agreement to Legislature, Administration Required to Submit Compensation Study. Section 19826 of the Government Code specifies that CalHR shall establish salary ranges for state classifications “based on the principle that like salaries shall be paid for comparable duties and responsibilities.” Further, the law requires that—when establishing or changing pay ranges—“consideration shall be given to the prevailing rates for comparable service in other public employment and in private business.” The law requires that “at least six months before the end of the term of an existing memorandum of understanding or immediately upon the reopening of negotiations under an existing memorandum of understanding” CalHR submit to the union that represents the affected employees and the Legislature “a report containing the department’s findings relating to the salaries of employees in comparable occupations in private industry and other governmental entities.” If this requirement under law conflicts with provisions of a ratified MOU, the law specifies that the ratified MOU shall be controlling.

A requirement that CalHR (or its predecessor agency, the Department of Personnel Administration [DPA]) submit a compensation study to the Legislature has existed under Section 19826 since 2001. Originally, the requirement was for the administration to submit the compensation study for all state employees with the Governor’s budget on January 10 each year. However, Chapter 465 of 2003 (SB 624, Committee on Public Employment and Retirement) amended the law so that the compensation study for a particular bargaining unit is due six months before the unit’s MOU expires. According to the bill analysis, Chapter 465 made this change to Section 19826 based on DPA arguments that an annual report is not necessary because collective bargaining for successor MOUs does not occur annually for all bargaining units. Clearly, the intent of the current reporting requirement is for the compensation study to be a resource used during the collective bargaining process.

Compensation Studies Contextualize State Employee Compensation in the Labor Market. CalHR’s compensation study provides important information to understand how the state’s compensation for a particular occupation is situated within the broader labor market. We rely on this information when preparing our analysis of proposed MOUs for the Legislature. With the compensation study being due to the Legislature before bargaining has started for a successor agreement, the intent of state law was not just for the Legislature to be informed but also that the administration use the information it acquires through the compensation study to prepare for bargaining. Since 2013, the compensation studies have included the following information:

Median Wages and Benefits. The studies report the median wages and median benefit costs provided by the state employer and similar local governmental, private sector, and federal government employers. Based on this information, the studies report the extent to which state total compensation for a particular occupation is below (lags) or above (leads) compensation provided by other employers and the market average.

Geographic Differences in Compensation. The studies report the extent to which state employee compensation lags or leads in different regions across the state. Because state compensation generally is established so that one salary schedule applies to all employees in a classification, regardless of geographic location, there can be significant disparity in the lag/lead of state compensation by region, depending on local labor markets.

Expected Growth for Occupation. The studies report information about the expected growth in an occupation over the next ten years. This information can be helpful in understanding what kind of pressure will exist in the future to increase compensation levels for particular occupations in order to compete with other employers.

Demographic Information. The studies report demographic information comparing the age, years of state service, and turnover rates (including involuntary separation rates, voluntary separation rates, and retirement rates) of state employees across different occupations or bargaining units.

Additional Data Points Provide More Context for State Employee Compensation Levels. Although a compensation study provides important information to contextualize state compensation in the labor market, other factors should be considered when determining whether the state provides adequate and reasonable compensation to attract and retain qualified employees. These other factors include quantifiable information such as the share of established positions that are vacant; the number of qualified applicants per posted position; or the number of qualified applicants for a required training program, like a peace officer academy. In addition, more qualitative information can be helpful, such as job satisfaction surveys or information from hiring managers that there could be a problem recruiting and retaining people. Unfortunately, these other sources of information are not always available during our ten-day review. Accordingly, the compensation study is one of the main tools we use in our analysis.

Upcoming MOUs

Legislature Expected to Consider MOUs for Eight Bargaining Units in 2020. In December 2019, the administration submitted to the Legislature a proposed MOU between the state and Bargaining Unit 18 (Psychiatric Technicians). By July 2020, the MOUs with seven other bargaining units will expire—Units 2 (Attorneys and Hearing Officers), 6 (Correctional Officers and Parole Agents), 9 (Professional Engineers), 10 (Scientists), 12 (Craft and Maintenance Workers), 16 (Physicians, Dentists, and Podiatrists), and 19 (Health and Social Services Professionals). We expect the Legislature will be asked to consider successor MOUs for these seven agreements before the end of the legislative session in August.

Assessment of Bargaining Units Without New Compensation Studies

Administration Not Expected to Submit New Compensation Studies for Unit 2 and Unit 6. The administration submitted to the Legislature compensation studies for Bargaining Units 9, 10, 12, 16, 18, and 19 within six months of each bargaining unit’s agreement expiring. The administration did not, and is not expected to, submit a compensation study for Units 2 or 6 in 2020. As we discuss in this section, this is not particularly problematic for Unit 2; however, it is problematic in the case of Unit 6, especially if the administration submits a multiyear agreement to the Legislature for ratification.

Unit 2

Three Recent Compensation Studies Identify Lag in State Compensation for Attorneys. In addition to the official compensation study compiled by CalHR, two other compensation studies (one conducted by the California Department of Justice and the other conducted by the University of California at Los Angeles) provided to us by the union that represents attorneys (California Attorneys, Administrative Law Judges, and Hearing Officers in State Employment [CASE]) identified significant lags between state attorney compensation and attorneys employed by local governments. Statewide, the studies found that state attorney compensation lagged local government compensation by between 10 percent and 23 percent. The studies identified greater lags in high cost-of-living regions of the state ranging from 17 percent to 30 percent. For specific information about the findings of these three compensation studies, please refer to our analysis of the 2019 Unit 2 MOU. The variation in the findings of the studies likely is due to methodological differences and the level of specificity of each study. However, the overall conclusion of the studies are the same: recent studies (using data from 2017, 2018, and 2019) identify a significant lag in state attorney compensation compared with local governmental employers. On the whole, based on the findings of these studies as well as vacancy data on attorney classifications, we think there is sufficient evidence that Unit 2 attorneys are compensated at levels lower than their local government counterparts and that this lag may result in recruitment and retention issues.

Since 2014, Unit 2 MOU Has Included Commitment From State to Work to Reduce Lag. Although the administration has not agreed to compensation increases that address the lag in attorney compensation, it has agreed that a lag exists since 2014. Specifically, a provision (Provision 15.9) has been in the Unit 2 MOU since 2014 that suggests that the state and union agree that the lag in compensation exists and that it should be addressed. Specifically, this provision (titled “Salary Gap and Statewide Legal Professional Classification Issue”) requires CASE and the state to begin negotiating a successor agreement no later than six months prior to the expiration of the MOU and specifies that the parties will begin negotiations “with the intent of developing a joint economic proposal for the successor MOU, designed to significantly reduce the pay disparity, if economically feasible as determined by the State, for CASE members in comparison to other public sector legal professionals.” Despite the strong fiscal position of the state in recent years, the pay disparity between Unit 2 members and their local government counterparts persists.

Current Agreement Includes Provision to Wave CalHR Compensation Study for One Year. The current MOU includes a provision (Article 15.7) that clearly establishes that no compensation study will be produced in 2020 based on the recognition that the most recent Unit 2 CalHR compensation study was relatively recent and the term of the agreement is only one year. Specifically, the language states:

In January 2020, the parties will meet to explore the components and methodology for conducting a salary survey. Nothing in this section shall require the State to modify their existing total compensation methodology.

The parties understand that due to the recent release of the total compensation survey and the one year duration of this contract, the state shall not conduct a total compensation survey during the term of this agreement.

Unit 6

Last Unit 6 Compensation Study—From 2013—Showed State Leads by 40 Percent in Compensation for Correctional Officers. The last compensation study for Unit 6 was conducted using data from 2013 (the report was produced in 2015). That survey determined that correctional officers represented by Unit 6 received total compensation that was 40 percent higher than their local government counterparts. Since the time that the compensation study was released in 2015, the Legislature ratified Unit 6 MOUs in 2016 (the 2016 MOU), 2018 (the 2018 MOU), and 2019 (the 2019 MOU).

Administration Completed, but Will Not Submit to the Legislature, a 2018 Compensation Study… As we describe in greater detail in our analysis of the 2019 MOU, the 2016 MOU included language that (1) established criteria for the union that represents Unit 6 (California Correctional Peace Officers’ Association [CCPOA]) and the administration to meet to establish the methodologies that CalHR would use before CalHR conducted its compensation study and (2) allotted a full year for the union and the administration to meet and for CalHR to complete and submit to the Legislature and union the study six months before the 2016 MOU expired.

When we reviewed the 2018 MOU, CalHR informed us that (1) the administration and CCPOA met beginning August 2017 and reached a consensus on the study’s methodology by mid-October 2017, (2) the survey was mailed to six county employers in mid-October 2017, (3) CalHR completed a draft compensation report by mid-February 2018, (4) CalHR shared a draft report with CCPOA, (5) CCPOA had questions about how the agreed upon methodology was applied in the study, and (6) CalHR agreed not to submit to the Legislature the 2018 compensation study until CCPOA had completed its review. Two years later, CalHR indicates that the union and administration still have not resolved their differences on the compensation study and do not plan on submitting to the Legislature the 2018 study.

…And Did Not Conduct a 2019 Compensation Study for Current Agreement… The ratified 2018 MOU specified that the section of the 2016 MOU referenced above “will be inoperable during the term of this MOU.” With this provision of the agreement inoperable, Section 19826 is controlling and CalHR should have submitted to the Legislature a compensation study six months before the expiration of the 2018 MOU. However, CalHR did not submit a compensation study to the Legislature in 2019. As we indicated in our analysis, at the time we reviewed the current MOU—the 2019 MOU—CalHR indicated that the administration did not submit a 2019 compensation study because the parties never reached agreement on a compensation study methodology. Because Section 19826 is controlling under the 2018 MOU, whether or not the union agreed with the methodology used in a 2019 compensation study is immaterial.

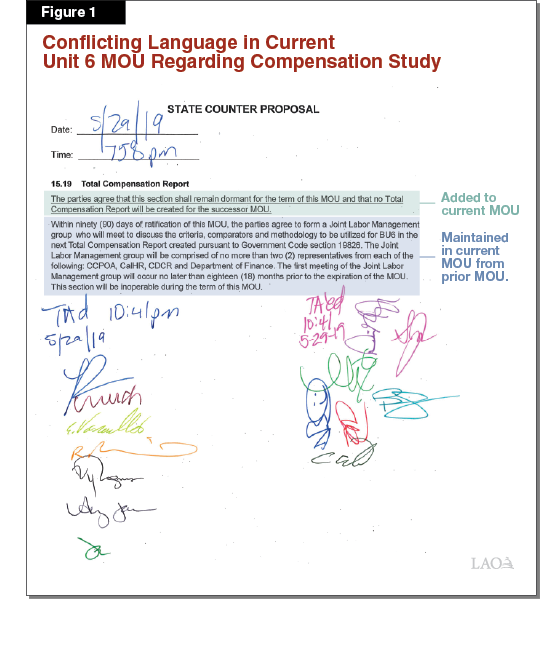

…And Will Not Submit New Compensation Study in 2020. The current agreement includes conflicting language as to whether a compensation study will be submitted to the Legislature before the Legislature is asked to approve a successor agreement. Figure 1 shows the provision from the agreement that was submitted to the Legislature last year. Proposed MOUs include strikethrough and underline to denote deletions and additions to text of the agreement relative to prior versions of the provision, similar to how amendments to legislation are reflected. As can be seen from Figure 1, the first sentence was added to the current MOU; however, importantly, the last sentence was not deleted from the current agreement. Reading the provision in full, the last sentence makes all preceding sentences inoperable—including the sentence declaring that “no compensation report will be created for the successor MOU.” This would mean that Section 19826 would be controlling and the administration should have submitted a new compensation study in January 2020—six months before the expiration of the current agreement. The administration argues that, because the first sentence is most recent, the first sentence overrides the last sentence. Accordingly, CalHR plans not to submit a compensation study to the Legislature before it asks the Legislature to consider a successor agreement.

Importance of Compensation Studies

Increases to Compensation for Current Employees Has Fiscal Effects for Years to Come. The rank-and-file employees and managers associated with the eight bargaining units with MOUs that the Legislature likely will consider in 2020 account for 37 percent of the state workforce and 58 percent of the state’s General Fund payroll costs. Although some MOUs are in effect for only one year, more commonly MOUs are multiyear agreements in effect for at least two years. Through these agreements, the Legislature will be asked to establish the state’s salary and benefit levels for a majority of the state’s General Fund payroll for the next few years. Multiyear agreements could lock in General Fund cost increases during a downturn, limiting the Legislature’s options to contain General Fund costs. In addition to near-term fiscal considerations, salary increases have very long-term fiscal effects as (1) salary increases compound and (2) pension benefits ultimately are based on salary.

Important That Proposed Increases to Compensation Be Justified. We often recommend that the Legislature consider a proposed MOU in the context of the state budget. Through the budget process, the Legislature identifies what programs should have a higher priority in receiving a portion of the state’s limited resources. Employee compensation is a significant portion of the state budget—totaling about $28 billion (including state costs to active and retired state employees) in 2017‑18. Choosing to dedicate state funds to increase employee compensation for one group of employees means that the Legislature is choosing not to spend that money on some other program. Although the Legislature has the authority to reduce employee compensation, such action is difficult and rarely invoked. As such, a multiyear MOU effectively commits the state to a level of spending for the next few years to the programs staffed by the employees subject to the MOU. With so many competing priorities in the state budget, ensuring the administration justifies employee compensation increases and identifies how the cost increases will improve the state’s ability to provide a particular service is important. This becomes especially important if the Legislature is asked to approve a multiyear agreement at some point within the next few months given the increasingly uncertain fiscal picture.

Compensation Study Important for Justifying Need for Compensation Increases. Because each bargaining unit is unique, the administration might have different reasons to justify specific compensation increases for different bargaining units. However, the overall total compensation should aim to ensure that the state is able to recruit and retain qualified employees to provide a desired level of service to the public. The compensation study might not be a perfect tool—outcomes can vary significantly depending on methodologies and quality of data used—but it is the best resource available to the Legislature at the time that it considers a proposed MOU in order to understand whether compensation is set at an appropriate level to allow the state to compete in the labor market. Further, the administration should use the compensation study—in addition to other information—as a tool to develop its position at the bargaining table. When determining how to use the state’s limited resources efficiently, the Legislature and administration likely should place a higher priority on increasing compensation for employee groups where state compensation lags or there are significant recruitment challenges. When a compensation study shows that an employee group is compensated at or above market levels—or when the administration does not submit a compensation study—the administration has a burden to demonstrate why increasing employee compensation is necessary to maintain or improve current service levels.

Not Knowing How State Compensation Compares With Other Employers Creates Potential for Big Lags or Leads by End of Multiyear Agreements. A compensation study provides a snapshot of how the state’s compensation for particular workers compares with the compensation provided by other employers at one particular point in time. In the years following the compensation study, the state and the other employers make different decisions with regards to employee compensation. These different decisions lead to the differences between the compensation provided by the employers to vary over time. Agreements with shorter durations allow the state to keep a closer eye on its position in the labor market and ensure that any existing lag or lead does not widen. Multiyear agreements—especially agreements that are longer than two or three years—prevent the state from making regular assessments on its compensation policies. In the cases where the state lags other employers, a lack of regular assessment can result in whatever recruitment and retention issues that exist for that occupation to worsen. In the cases where the state leads other employers, a lack of regular assessment can result in the state dedicating more of its limited resources than is necessary to a particular state program.

Lack of Up-to-Date Information Inhibits Oversight. The Legislature is the final step of the collective bargaining process. Its role primarily is an oversight function to ensure that the administration is establishing reasonable levels of compensation for state employees. If—in this oversight capacity—the Legislature finds that proposed compensation levels are not reasonable, the Legislature has authority to reject proposed MOUs and change employee compensation levels in the budget. One purpose of the compensation study required by Section 19826 is to provide the Legislature timely information about state employee compensation so that it can exercise its oversight function when the administration proposes an MOU. When the administration does not comply with the law and withholds completed compensation studies, the administration weakens legislative oversight authority.

Recommendation

Without a Recent Compensation Study, Do Not Approve New MOUs With Term of Greater Than One Year. The Legislature’s oversight and appropriation authority requires that the administration justify proposals to increase state costs. With regards to proposed increases in employee compensation costs, Section 19826 requires the administration to submit a compensation study either before or immediately when negotiations begin between CalHR and bargaining units. This compensation study gives all parties involved in the collective bargaining process—the administration, union, employees, and Legislature—a common baseline against which to assess how state compensation compares with other employers. Without this information, the parties have insufficient information to assess how changes in compensation agreed to at the table might affect the state’s ability to recruit and retain qualified employees in the labor market. In such cases, what analytical process the administration uses to determine what level of compensation would be appropriate is unclear. Accordingly, if the Legislature has not received a recent compensation study—generally meaning a compensation study that uses data from the past few years—we recommend that the Legislature not approve proposed MOUs with terms of more than one year.

Do Not Approve Labor Agreements That Allow Administration to Not Submit Recent Compensation Study to the Legislature. Provisions within MOUs to establish certain criteria for compensation studies is reasonable. (For example, the exemption in the current Unit 2 MOU is reasonable.) However, we recommend the Legislature not approve MOUs that contain provisions (1) that allow the administration to submit a successor agreement without a recent compensation study being available to the Legislature and (2) with ambiguous language as to whether or not a compensation study is required before a successor agreement is submitted to the Legislature.

Applying Recommendation to the 2020 Bargaining Cycle. The Legislature has recent compensation studies for seven of the eight bargaining units likely to submit proposed MOUs for ratification in 2020. The last compensation study submitted to the Legislature for Unit 6 used data that is seven years old. Without new evidence to suggest otherwise, the lead in state correctional officer compensation that existed in 2013 likely continues. Unless the administration submits the 2018 compensation study or a newer study to the Legislature, we recommend that the Legislature not approve a Unit 6 agreement that has a term of greater than one year. If CCPOA continues to have concerns with how the administration implemented the agreed upon methodology when it developed the 2018 compensation study, the union can submit a letter that accompanies the compensation study outlining where the parties disagree with the study’s findings. The Legislature could then weigh the findings of the 2018 compensation study and the union’s concerns to determine whether or not proposed compensation increases are justified. Considering the significant economic uncertainty that exists today, the Legislature could choose to act on all of the pending MOUs at the same time at the end of session to give more time for the economic picture to become a little clearer.