LAO Contact

March 23, 2020

The 2020-21 Budget

Expanding the Minimum

Franchise Tax Exemption

Summary

The 2020‑21 Governor’s budget includes a proposal to expand an exemption from the state’s $800 minimum franchise tax, which the state annually imposes on many companies that do business here. The change would reduce General Fund revenue by about $100 million per year. In this budget analysis brief, we provide background information on the current tax expenditure and assess the merits of the administration’s proposal to expand it. We conclude that the Legislature should reject the Governor’s proposal. We further suggest the Legislature reconsider the current exemption.

Background

Many California Businesses Pay a Minimum Franchise Tax. Corporations doing business in California must pay a state corporation tax (CT) on their net income. Many corporations have no net income in California, but are still required to pay an annual minimum franchise tax of $800. Other types of noncorporate businesses are not subject to the CT, but many also are required to pay an annual minimum franchise tax of $800. (Businesses that are organized or located in other states are subject to the tax if their California sales, property, or payroll exceed certain thresholds.) The minimum franchise tax ensures that all of these businesses pay a minimum amount of tax for the right to conduct business here and for the benefits of limited liability protection, meaning their owners are not personally liable for the business’s debts. The most common noncorporate businesses subject to the minimum franchise tax include limited liability companies (LLCs), limited partnerships (LPs), and limited liability partnerships (LLPs). We describe these in the nearby box. In 2017, 1.6 million businesses were subject to the minimum franchise tax. Figure 1 shows the number of business tax filers of each type and the amounts of minimum franchise tax paid in 2017. Altogether, the state annually collects about $1 billion from the minimum tax.

Types of Businesses

Businesses Are Organized In Different Ways. Businesses take a variety of forms depending on the complexity of their ownership and management structure. The organizational form of a business determines how the federal and state governments tax the business and its owners. The primary considerations for determining which form to take include the number of owners, whether the owners are all actively involved in managing the business, and whether the owners need or want protection from financial liabilities.

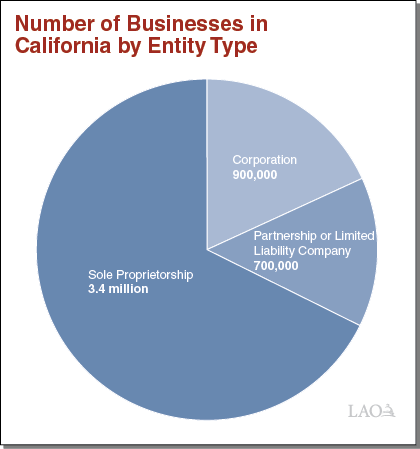

Sole Proprietorships and General Partnerships Are Owned and Principally Managed by Individuals. A sole proprietorship, owned and managed by an individual, is the most basic and most prevalent form of business entity. As we show in the nearby figure, nearly 70 percent of California’s 5 million businesses are sole proprietorships. When two or more individuals decide to jointly own and operate a business, they form a partnership. A general partnership is similar to a sole proprietorship in that the owners are equally responsible for any debts or other liabilities of the business.

Limited Liability Protection for Business Owners. Unlike general partnerships, limited partnerships (LPs) and limited liability partnerships (LLPs) provide business owners with limited liability protection. This means that the owners are not personally liable for the business’s debts. An individual or another company may be a partner in an LP or LLP.

Corporations and Limited Liability Companies (LLCs) Are Legally Distinct Business Entities. An LLC is a business that is legally distinct from its owners (members). An LLC may not provide professional services or be a bank, insurer, or trust company. A professional services business is one owned by one or more individuals who have a state professional license, such as an engineer, accountant, or chiropractor. A corporation also is a business that is legally distinct from its owners (shareholders). Individuals or companies may own an LLC or a corporation. An LLC or a corporation may have just a single member or shareholder.

Figure 1

California Businesses Pay $1 Billion in Minimum Franchise Tax Per Year

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Business Structure |

Number of Taxpayers |

Pass‑ Through Businessa |

Limited Liability Protection? |

Subject to Minimum Franchise Tax? |

Other State Tax or Fee? |

Minimum Franchise Tax Collections |

Total Corporation Tax and Fee Collectionsb |

|

Corporations |

|||||||

|

C corporation |

342,000 |

x |

x |

8.84 percent tax on income. |

$173 |

$7,381 |

|

|

S corporation |

615,000 |

x |

x |

x |

1.5 percent tax on income. |

305 |

1,502 |

|

Partnerships |

|

||||||

|

Limited liability company |

567,000 |

x |

x |

x |

Income‑based fee. |

454 |

1,044 |

|

Limited partnership |

71,000 |

x |

x |

x |

57 |

57 |

|

|

Limited liability partnership |

6,000 |

x |

x |

x |

5 |

5 |

|

|

Totals |

1,601,000 |

$994 |

$9,990 |

||||

|

a“Pass through” means that the business is not directly taxed under federal law. The business income instead passes through to the owner (or owners) of the business who pay personal income tax (PIT) on their business income. bThese amounts do not include any additional state and local taxes and fees paid by the owners of these businesses including PIT, sales and use tax, and property tax. |

|||||||

Corporations Exempted From Paying Minimum Franchise Tax in First Year of Business. Since 1998, newly formed corporations have been exempted from paying the $800 minimum franchise tax in their first year of business. About 100,000 new corporations are formed each year. However, the Franchise Tax Board (FTB) reports that only about three‑quarters of new corporations claim the exemption because many new corporations do not understand their tax filing requirements. Overall, the exemption reduced state revenue by $60 million in 2017 (the most recent year for which data are available). Other newly formed business entities that are subject to the minimum franchise tax, such as LLCs and LPs, cannot claim this exemption.

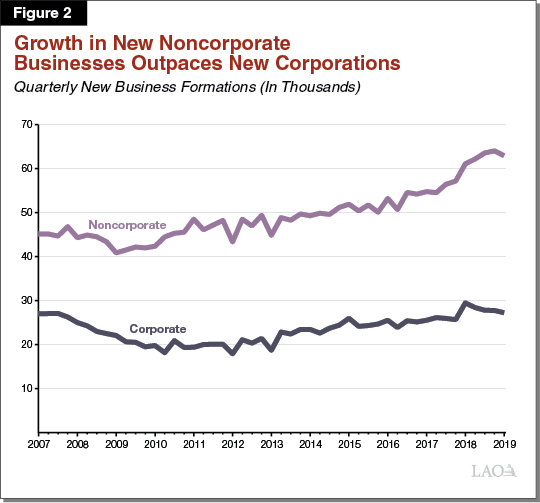

Growth in Number of New Noncorporate Businesses Outpaces Growth in New Corporations. In recent years, new business formation in California has grown steadily and kept pace with the rest of the country. In addition to new corporations, about 250,000 LLCs, partnerships, and sole proprietorships are formed in California each year. Figure 2 shows that the rate of growth in new business formations has increased by about 3 percent per year since 2007, according to U.S. Census data. New business formation has been strongest among noncorporate businesses, despite these businesses not being eligible for the first‑year exemption from the minimum franchise tax. In particular, FTB reports that new LLC registrations with the Secretary of State have increase by about 7 percent per year since 2007.

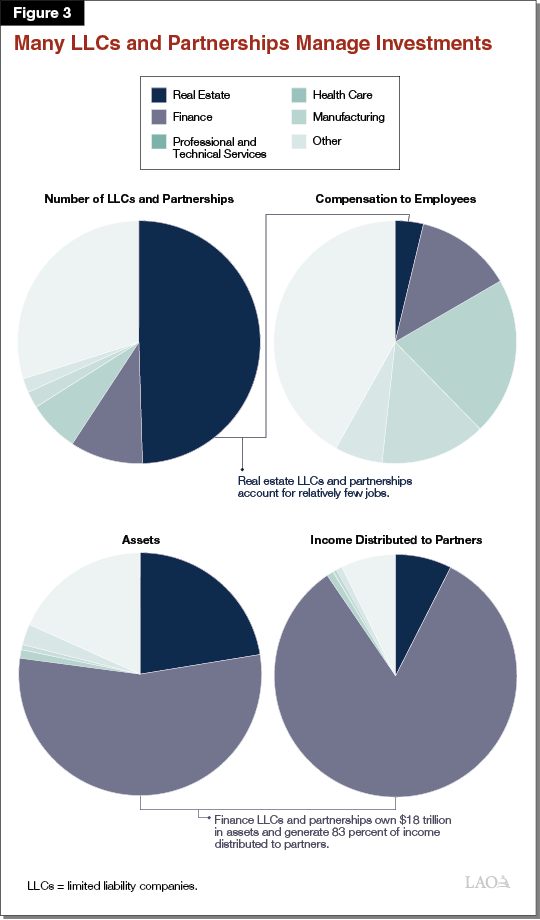

Many Business Entities Exist to Manage Investments. A significant number of new companies are formed each year to independently hold and manage investments. For example:

- Energy and real estate development companies commonly form new partnerships to attract financing for new projects.

- Many real estate leasing companies create a new, legally independent company to hold each property that they own.

- Financial companies primarily exist to manage their owners’ investments and assets.

The Internal Revenue Service reports that half of all LLCs and partnerships in the U.S. are real estate rental and leasing businesses and 10 percent are financial companies. (FTB does not provide similar statistics on LLCs and partnerships in California.) As shown in Figure 3, these businesses create relatively few jobs compared to companies in other industries. Nonetheless, finance and real estate companies often hold significant assets. Figure 3 shows that financial companies own 55 percent—nearly $18 trillion in 2017—of the total assets owned by all LLCs and partnerships.

Governor’s Proposal

Extend the First‑Year Minimum Franchise Tax Exemption to Noncorporate Businesses. The administration has proposed to extend the first‑year exemption from the $800 minimum franchise tax to LLCs, LPs, and LLPs. The Governor’s budget assumes the expansion of the exemption will result in a reduction of $50 million in General Fund revenues in 2020‑21 and $100 million in 2021‑22 and out‑years. This estimate assumes that about 125,000 new eligible noncorporate taxpayers claim the exemption each year. (The revenue assumption also makes a rough adjustment for the timing of the revenue effect in the first year.) The exemption for LLCs, LPs, and LLPs would sunset on January 1, 2026. The FTB also would be required to annually report the number of first‑year businesses that are affected by the exemption.

Assessment

Tax Exemption Lacks a Strong Policy Justification

The Minimum Franchise Tax Exemption Has Not Been Closely Reviewed. Like many of the state’s tax expenditures, the minimum franchise tax exemption is not regularly reviewed, has no sunset date, and its effectiveness has never been evaluated. In our 2019 post on evaluating tax expenditures, we explain that periodically reviewing tax expenditures is important because, like direct state expenditures, they have budgetary costs. Such reviews can help policymakers assess whether a tax expenditure is effective and merits continued financial support from the taxpayers.

Good Tax Policy Should Treat Similar Taxpayers Similarly. In general, the state’s tax laws should treat businesses differently only to serve a clear policy goal. We see no obvious public policy benefit for the status quo of exempting a newly formed corporation from the minimum franchise tax, while a newly formed LLC, LP, or LLP must pay the minimum franchise tax. That being said, there are two ways for the Legislature to address this unequal treatment: (1) extend the exemption to LLCs, LPs, and LLPs as the Governor proposes or (2) eliminate the exemption entirely. We suggest that the Legislature consider whether the exemption achieves a clear policy goal. If the exemption does achieve a clear policy goal, extending it is reasonable. Otherwise, the Legislature should consider eliminating the exemption for all businesses.

Current Exemption and Proposal Lack a Strong Policy Justification. The stated Legislative intent of the current first‑year minimum franchise tax exemption is to promote small businesses by reducing the burden of the minimum franchise tax. The Governor’s proposal to extend the exemption to new noncorporate businesses uses similar language. There are several reasons to think the exemption is an ineffective and poorly targeted means of promoting small business, which we discuss below.

Difficult to Identify Small Businesses. Small businesses are difficult to target in the tax code. In large part, this is because a “small business” is difficult to define and the definitions that currently are used can vary across different industries. In addition, definitions typically rely on simple thresholds, such as the number of employees or annual revenue, for practical reasons. These thresholds may not always reliably distinguish small businesses. For example, a small business in a labor‑intensive industry, such as a retailer or restauranteur, will employ many people, while a large financial investment firm with significant assets might employ far fewer staff.

Exemption Poorly Targets Small Business. The exemption attempts to avoid the challenge of defining which taxpayers are small businesses by instead targeting benefits at newly formed companies. This strategy poorly targets small business. Benefits from the exemption go to many companies that do not seem to meet any reasonable definition of a small business. For example, major companies routinely form new corporations to facilitate financial transactions, raise capital, and manage risk. Distinguishing between these new entities and actual small businesses often is not possible from the information currently reported on tax forms. Similar problems would exist if the exemption were expanded to LLCs, LPs, and LLPs. About one‑third of LLCs, LPs, and LLPs are owned by corporations or other companies and not by individuals. In addition, as discussed earlier, many new LLCs, LPs, and LLPs are formed to hold and manage real estate property and other investments. Many of these companies have significant assets, but generate comparatively little economic activity in the way of buying and selling goods or employing workers.

Provides Limited Relief to Businesses. Many businesses undoubtedly consider the $800 minimum franchise tax an unwelcome cost of doing business in California. In most cases, however, the one‑time tax exemption provides a relatively limited amount of financial assistance to new businesses relative to the overall cost of starting a new business. These costs—such as equipment, construction costs, employee salaries, and rent—often sum to tens of thousands of dollars, or considerably more. The number of LLCs (which do not receive an exemption) has grown more quickly than the number of corporations (which do receive an exemption) in recent years. While not conclusive, this suggests that the lack of the first‑year minimum franchise tax exemption has not significantly hindered the formation of new businesses.

Other Issues

Current Exemption May Obfuscate Tax Filing Requirements. About 25 percent of new companies do not file a timely corporate tax return in their first year of business. We are concerned that the exemption itself may be confusing new companies that might infer that they are not required to file a tax return because they are exempt from the minimum franchise tax in their first year. Taxpayers who do not file a timely tax return may be subject to penalties and interest. Such treatment of new businesses seems to be at odds with the intent of assisting small businesses that are less likely to have access to experienced state tax advisors.

Proposed Reporting Requirements Add Little Value. The proposal would require FTB to report the number of first‑year businesses claiming the exemption, including corporations. The Department of Finance (DOF) already is required to report this information in its annual tax expenditure report. Simply reporting the number of total exemption claims would not help the state to understand how many small businesses specifically would benefit from the provision, nor to estimate the effectiveness of the provision in stimulating new business formation.

Budget Year Cost Likely More Than $50 Million. The proposal likely will cost somewhat more than $50 million in 2020‑21. While corporations pay the CT four months after the end of the tax year, corporations and noncorporate businesses must pay the minimum franchise tax during the taxable year. (For corporations, the minimum franchise tax affects the amount of their first estimated tax payment.) The DOF appears to have based their assumption about when the state collects the minimum franchise tax on guidelines used for estimating the CT. This likely understates the cost in 2020‑21. FTB estimates the proposal will cost up to $110 million in 2020‑21.

Out‑Year Cost May Be More or Less Than $100 Million Per Year. The DOF has assumed the proposal would cost $100 million annually in the out‑years. This assumption is based on a 9 percent annual rate of growth in the formation of new LLCs. This assumption may be reasonable, given the amount of uncertainty regarding the future rate of business formations, but it is somewhat faster than the historical average of 7 percent. A slower rate of LLC formation would result in the proposal having a somewhat lower cost, while a faster rate of LLC formation would result in a higher cost.

Recommendations

Reject Proposal To Extend First‑Year Minimum Franchise Tax Exemption. We recommend rejecting the administration’s proposal to exempt LLCs, LPs, and LLPs from paying the $800 minimum franchise tax in their first year of business. Extending the exemption appears to be an inefficient way to promote small businesses.

Reconsider Current Exemption for Corporations. Although we recommend rejecting an extension of the first‑year exemption to LLCs, LPs, and LLPs, there could be merit in eliminating the current differential tax treatment of these businesses. Given the limited benefit of the current exemption for corporations and the difficulty of targeting small businesses, we recommend the Legislature at some point consider addressing this differential treatment by ending the exemption for corporations.

Fiscal Effect of Our Recommendations. The budget assumes the Governor’s proposal would have reduced General Fund revenues by $50 million in 2020‑21 and $100 million in 2021‑22 and out‑years. Ending the exemption for corporations would increase General Fund revenues by more than $60 million. Relative to the Governor’s budget, these two actions would increase revenues by about $110 million in 2020‑21 and about $160 million per year thereafter.

Conclusion

Two decades ago, the Legislature adopted an exemption from the state’s minimum franchise tax for corporations in their first year of business with the stated intent to provide financial assistance to small businesses. This provision instead provides limited, broad‑based tax relief to nearly all new corporations, including many that probably do not meet any reasonable definition of a small business. The Governor’s proposal would expand this poorly targeted tax expenditure to LLCs, LPs, and LLCs, without articulating a specific policy problem the provision would solve. We, therefore, recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal. Furthermore, we recommend at some point reconsidering the existing exemption for corporations. We recognize that, especially in light of the growing economic impact of the COVID‑19 outbreak, there is a general interest in supporting small businesses. However, expanding this poorly targeted tax expenditure is not a good option for achieving this goal. We suggest the Legislature explore other options.