What Are Tax Expenditures?

Tax Provisions Intended to Accomplish A Public Policy Goal. Tax expenditures are provisions of tax law that enable targeted groups to reduce their taxes relative to the “basic” tax structure. As our office explained in 1983, the primary reasons tax expenditures are adopted are either to encourage certain types of behavior or to provide financial assistance to certain taxpayers. For example, the state has sales tax exemptions intended to encourage businesses to purchase certain types of manufacturing equipment. Tax expenditure provisions also can include exemptions, special deductions, preferential tax rates, and tax credits. See this detailed post written by our office in 2015 for additional background information about tax expenditures.

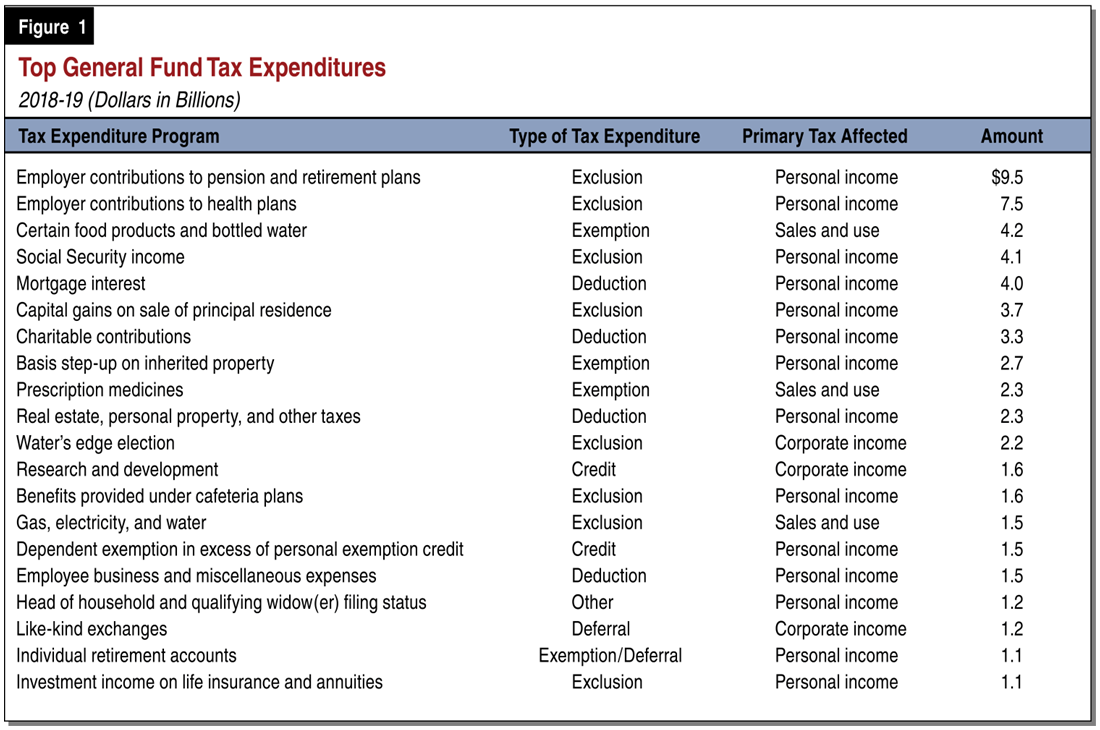

Tax Expenditures Reduce General Fund Revenues by $65 Billion. The Department of Finance (DOF) annually reports information about state tax expenditures. These reports are available online and are the primary source of data for the information that follows. In 2018-19, tax expenditures reduced state General Fund revenues by an estimated $65 billion. Of this amount, 75 percent—or $49 billion—were provisions of the personal income tax (PIT) and 10 percent—or $7 billion—were provisions of the corporation tax. Sales and use tax (SUT) expenditures reduce General Fund revenues by $10 billion. (These sales and use tax expenditures also reduce local government revenues by an additional $11 billion.) Figure 1 lists the state’s largest General Fund tax expenditures.

Evaluating Tax Expenditures is Important. Periodically reviewing tax expenditures is important because, like direct state expenditures, they have budgetary costs. These reviews can help policymakers assess whether the tax expenditures are effective and merit continued financial support from the taxpayers.

Tax Expenditure Oversight Relatively Limited

Compared to Other State Expenditures, Most Tax Expenditures Not Routinely Reviewed. Unlike direct expenditure programs, tax expenditures are not reviewed and funded during the course of the annual state budget process. Most tax expenditures are long-standing provisions in state law that provide large benefits to some taxpayers. For example, the PIT provisions that exclude employer contributions to health insurance plans and qualified retirement plans from the definition of taxable income have been in state law since at least 1983. These provisions respectively cost an estimated $7.5 billion and $9.5 billion annually, but they are not routinely reviewed and they have no sunset date.

Some Tax Expenditures Have Greater Oversight. The Legislature subjects some tax expenditures to greater oversight. For example, the film and television production and California Competes tax credits have annual allocation limits and public disclosure requirements. Moreover, these provisions also have sunset dates so that the Legislature can periodically weigh the costs and benefits of these tax expenditures against other Legislative priorities.

State Tax Agencies Provide Some Information About Tax Expenditures. In addition to the DOF reports mentioned above, the state tax agencies—the Franchise Tax Board, Board of Equalization, Department of Tax and Fee Administration, and the Employment Development Department—also describe and report statistical data on tax expenditures.

Framework for Evaluating Tax Expenditures

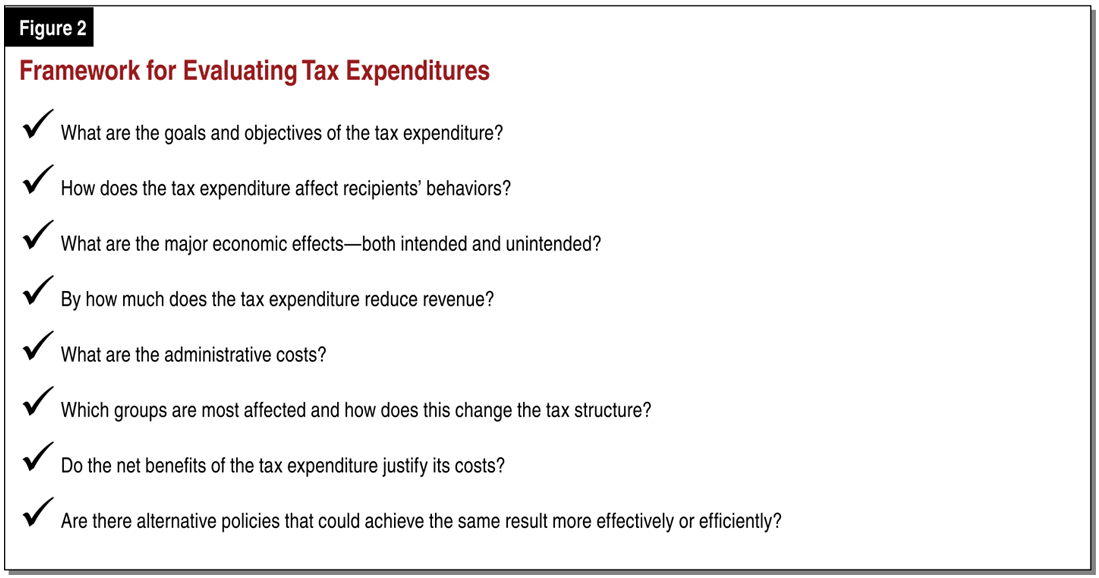

Over the years, our office has provided reports to the Legislature about the effects and administration of various tax expenditures based on data reported by the Department of Finance and the state’s tax agencies. In the remainder of this post, we explain our general approach to evaluating tax expenditures. Figure 2 summarizes our framework for evaluating tax expenditures. We also include a list of our more recent tax credit reports and evaluations at the end of this post.

What Is the Goal? Understanding what a tax expenditure is intended to achieve helps to frame the evaluation of its effectiveness. The Legislature clearly states the intent of some tax expenditures in the enacting legislation. For example, the stated intent of the California Competes tax credit is to “attract and retain high-value employers in the state.” In other cases, the intended goal may be less clear. When tax expenditure legislation lacks clear intent language, determining the primary goal may be more difficult. For example, some may see the goal of the exclusion for employer contributions to health insurance plans as increasing health insurance coverage, while others may see the goal as increasing the after-tax income of certain workers. Identifying these goals—and the intermediate objectives towards achieving them—is the first step in evaluating whether the tax expenditure is meeting its intended purpose.

What Are the Economic and Behavioral Effects? A tax expenditure provides a financial benefit to the tax filer for taking a specified action—such as saving money for retirement—or having a specified characteristic—such as being blind. The financial benefit increases the filer’s after-tax income and may change his or her behavior in various ways—both intended and unintended. For example, the mortgage interest deduction is intended to encourage homeownership by reducing the cost of owning a home. However, evidence suggests that the provision has instead promoted the purchase of larger and more expensive homes.

Identifying and estimating a tax expenditure’s major effects—both intended and otherwise—is necessary to evaluate whether it is meeting its goals and whether its benefits justify its costs. Some tax expenditures are relatively well understood in this regard. For example, extensive academic research and the availability of relatively good household income and labor market data allows us to estimate the likely effects of the state Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) with a relatively high degree of confidence: the EITC reduces poverty, increases labor force participation, and has other positive outcomes as well. At the same time, the EITC has some negative economic effects, such as reducing wages. More often, however, it is difficult to estimate the economic and behavioral effects of tax expenditures. There are several reasons for this, including data limitations, uncertain behavioral effects, indirect economic effects, and opportunity costs. We discuss these challenges in more detail below.

- Data Usually Limited. The appropriate data needed to measure key outcomes may be unavailable. For example, the state does not collect data on the number of people who benefit from most income exclusions and sales tax exemptions. Without this data, evaluating who receives tax expenditure benefits can be challenging.

- Behavioral Effects Difficult to Estimate. Understanding how the financial incentive of a tax expenditure might affect tax filers’ behaviors is the first step to understanding the provision’s effects. For example, the state research credit probably induces additional private spending on research activities. However, there is no straightforward way to determine how much would have been spent had the credit not been available. Under some circumstances, it is possible to make reasonable predictions or assumptions about what would have happened absent the tax expenditure to credibly estimate the policy’s effects. Additionally, some behavioral changes caused by a tax expenditure may have negative effects. The like-kind exchange provision—which allows filers to defer paying taxes on gains from some business transactions—may, for example, cause businesses to make less efficient investments. (We discussed the like-kind exchange provision in our analysis of the Governor’s 2019 tax conformity proposal).

- Indirect Economic Effects. Tax expenditures also have indirect economic effects. For example, if a business that receives a California Competes credit hires 100 new employees in California instead of in Texas, the indirect effects include the economic activity resulting from changes in the employees’ spending, income tax payments, and use of public services. To estimate these effects, we must consider whether these 100 new employees would otherwise have had similar jobs, lower-paying jobs, or no jobs—or whether they would have lived in another state rather than California.

- Opportunity Costs. Tax expenditures reduce the amount of tax revenue that is available for other purposes. The forgone benefits from alternative uses of that revenue—such as a different tax expenditure or public spending—are the opportunity cost of the tax expenditure. Estimating opportunity costs requires knowing how the Legislature would have otherwise allocated those resources. Typically, the opportunity cost is unknown. Entirely ignoring the opportunity cost, however, can significantly overstate the net economic benefits of a tax expenditure. For example, some tax expenditure evaluations estimate the economic activity generated by the tax expenditure but disregard the economic activity that would have been generated by an alternative use of the forgone revenue.

Despite these challenges and limitations, tax expenditure evaluations generally are worthwhile. These evaluations should describe and estimate the policy’s effects as clearly and accurately as possible, while acknowledging costs and benefits that are uncertain. An evaluation that only includes those effects that are best understood or most easily measured may be misleading.

What Are the Fiscal Effects? In addition to the net economic and behavioral effects, tax expenditure evaluations also weigh the fiscal costs. Tax expenditures have two types of direct fiscal costs: revenue losses and administrative costs.

- Revenue Losses. Tax expenditures reduce the amount of revenue the state collects. The DOF, with the assistance of the state tax agencies, calculates or estimates the amount of each tax expenditure. These are the amounts that appear in Figure 1 above. The costs of most credits and many deductions can be calculated accurately because tax filers report and itemize these on their tax returns. However, taxpayers and tax administrators generally do not collect detailed records of exclusions and exemptions, making the associated revenue losses harder to estimate. The estimated cost of the water’s edge election, for example, is imprecise because corporations that choose to report their income on a “water’s edge” basis provide no information about their excluded offshore income. In such cases, it may be possible to estimate the revenue losses by making some reasonable assumptions. Precise estimates are available for a few sales tax exemptions because the taxpayers must apply for them or list them separately on their tax returns.

- Administrative Costs. The costs of administering tax expenditures vary greatly. As most tax expenditures are changes to the prior tax system, the administration costs may be only the additional costs necessary to revise tax forms, respond to taxpayer inquiries, and audit tax claims. Other tax expenditures require the state to maintain relatively costly programs to receive applications from qualified taxpayers, verify eligibility, allocate the tax benefits, and monitor compliance.

How Does the Tax Expenditure Change the Tax Structure? Tax expenditures may have significant effects on the structure of the tax system. Policymakers often are interested in how a tax expenditure changes the amount of tax paid by some groups relative to others. There generally are two ways to think about the tax structure in this context: “horizontal equity” and “progressivity.”

- Horizontal Equity. Evaluations of horizontal equity examine the degree to which policies treat the individuals within a group consistently. For example, we raised concerns about the horizontal equity of the California Competes credit because some businesses receive large tax credits while other, similarly situated businesses, do not.

- Progressivity. Tax progressivity examines how much of a tax individuals pay relative to their income or wealth. If a tax expenditure results in higher-income individuals paying a larger proportion of the tax, the provision makes the tax structure more progressive. For example, the deduction for real estate, personal property, and other taxes makes the tax structure less progressive because high-income individuals benefit significantly more from this tax expenditure than do low-income individuals.

Is the Current Tax Expenditure the Best Way to Achieve the Goal? In considering the objectives of the tax expenditure, an evaluator should consider whether there are alternative policies that could achieve the same result more transparently, effectively, or efficiently. For example, the federal government provides an income tax credit to buyers of electric cars, but the state provides a cash subsidy instead. On one hand, tax expenditures can be relatively inexpensive to administer and can help achieve policy goals by influencing behavior. On the other hand, alternative policies sometimes can achieve comparable outcomes in a more targeted or less costly fashion.

Conclusion

Evaluating and estimating fiscal and economic effects of tax expenditures is often difficult but generally worthwhile. In principle, the best way to judge the effectiveness of a tax expenditure and to decide whether to continue providing it is to consider whether the benefits justify the costs. A direct quantitative comparison of benefits to costs faces two major challenges. First, the effects of the tax expenditure can be quite uncertain. Second, there often is no consensus about the relative value of each cost and benefit. Despite these challenges, an effective evaluation can provide valuable information about the intended and unintended effects of the policy. A comprehensive tax expenditure evaluation describes and estimates the effects as clearly and accurately as possible, while acknowledging costs and benefits that are uncertain. This information helps policymakers decide whether the tax expenditure should be continued or whether an alternative policy might be more effective or advantageous.

List of LAO Tax Expenditure Reports and Evaluations

The 2019-20 May Revision: Opportunity Zones, May 2019

The 2019-20 May Revision: Sales Tax Exemptions for Diapers and Menstrual Products, May 2019

The 2019-20 Budget: Tax Conformity, March 2019

Evaluation of a Sales Tax Exemption for Certain Manufacturers, December 2018

Review of the California Competes Tax Credit, October 2017

California's First Film Tax Credit Program, September 2016

Options for Modifying the State Child Care Tax Credit, April 2016

California State Tax Expenditures Total Around $55 Billion, February 2015

Options for a State Earned Income Tax Credit, December 2014

Housing-Related Tax Expenditure Programs, March 2013

Tax Expenditure Reviews, November 2007

An Overview of California's Enterprise Zone Hiring Credit, December 2003

An Overview of California’s Research and Development Credit, November 2003

An Overview of California's Manufacturers' Investment Credit, October 2002

California's Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, May 1990