LAO Contact

April 5, 2020

COVID-19

Update on State and School District Reserves

Updated 4/23/2020 to provide additional information on optional BSA balance.

As the Legislative Analyst recently noted, California could face a budget problem in the coming months. As the public health crisis has unfolded, this possibility seems increasingly likely. Revenues are likely to be at least several billions of dollars lower than anticipated in January for 2019‑20 and/or 2020‑21. This could mean that the costs of maintaining the state’s existing services would exceed revenue projections and the state would face a deficit—or a budget problem—in one or both years. If this is the case, the state will need to address the budget problem using some combination of tools. One key tool to solve a budget problem is reserves. This post assesses the current reserve situation of the state and school districts in California.

State Reserves

What Are the State’s Reserves?

Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties. The 1980‑81 Budget Act established within the General Fund the Reserve for Economic Uncertainties. In 1985, the fund was renamed the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU). Simply put, the SFEU is the difference between spending and available resources (most notably, revenues) for a given fiscal year. In any year, its balance (the amount by which resources available exceed spending) is the state’s discretionary reserve. Article IV of the State Constitution prohibits the Legislature from enacting a budget bill that would appropriate more in General Fund expenditures than are available in resources. (In this case, resources include both revenues as well as withdrawals from reserves.) In effect, this means the estimated balance of the SFEU—at the time of the budget’s passage—cannot be lower than zero.

Budget Stabilization Account (BSA). The BSA is the state’s general purpose constitutional reserve and it is governed by the rules of Proposition 2 (2014), which determine deposits into and withdrawals from the BSA. Under the measure, the amount of each annual deposit is determined as follows:

First, the state must set aside 1.5 percent of General Fund revenues (we refer to this as the “base amount”).

Second, the state must set aside a portion of capital gains revenues that exceed a specified threshold (we refer to this as “excess capital gains”).

The state combines these two amounts and then allocates half of the total to pay down eligible debts and the other half to increase the balance of the BSA. Under Proposition 2’s “true-up” provisions, the state reevaluates each year’s BSA deposit twice: once in each of the two subsequent budgets. The state does this because initial estimates of future capital gains revenues are highly uncertain.

Safety Net Reserve. The 2018‑19 budget created the Safety Net Reserve to set aside funds for future costs of two programs—California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids and Medi-Cal—in the event of a recession. Absent policy changes, these programs typically experience increased expenditures during a recession when unemployment increases and their caseloads rise.

How Much Does the State Have in Reserves?

Enacted 2019‑20 Reserves Most Relevant. Before updated revenue estimates in May, the most relevant figure for considering the amount of reserves that will be available to the Legislature as it passes the 2020‑21 budget is the enacted level from 2019‑20. (The proposed level from the 2020‑21 January budget, $20.5 billion, is the amount that would have existed in June 2021 under the Governor’s budget assumptions.) This is the amount the state currently had “in the bank” and—at the time of the Governor’s proposal—was available for expenditures in the next budget.

State Currently Has About $17.5 Billion in Reserves. As of February 2020, the state has $17.5 billion in reserves. This includes:

$16.5 Billion in the BSA. Since 2014-15, the state has deposited nearly $16.5 billion into its constitutional reserve. Most of this total—$13.4 billion—has been deposited pursuant to the rules under Proposition 2. However, the remaining $3.1 billion of the total is part of the “optional” balance of the fund because it was deposited on a voluntary basis or before Proposition 2 was enacted. (More information about the various components of the BSA balance is available here.)

$900 Million in the Safety Net Reserve. The Safety Net Reserve currently has a $900 million balance.

BSA Balance Will Adjust Automatically to New Revenue Estimates. The “true down” provisions of Proposition 2 will automatically adjust the balance of the BSA pursuant to new revenue estimates. (The state will adopt new revenue estimates for the purposes of the budget enacted in June.) The 2019‑20 balance of the BSA could be trued down—or automatically reduced—by around $2 billion if capital gains revenues are estimated to be lower by at least a few billion dollars in that year. While this would mean that the BSA balance would be lowered to $14.5 billion, these funds would become available to offset a budget problem.

How Can the State Access Its Reserves?

Accessing Mandatory BSA Requires Fiscal Emergency Declaration. Beyond the automatic adjustments to the BSA under the true down rules, the Legislature also can make a withdrawal from the mandatory share of the BSA in the case of a budget emergency. This can only occur upon declaration by the Governor and majority votes of both houses of the Legislature. The Governor may call a budget emergency in two cases: (1) if estimated resources in the current or upcoming fiscal year are insufficient to keep spending at the level of the highest of the prior three budgets, adjusted for inflation and population (a “fiscal budget emergency”) or (2) in response to a natural or man-made disaster. If the state faces a budget problem for either (or both) 2019‑20 or 2020‑21, the conditions for a fiscal emergency likely will be met.

Good Argument That Legislature Can Access Optional BSA Balance by Majority Vote. Although it has not yet been tested, we think there is an argument that the $3.1 billion balance of the BSA that was deposited on an “optional” basis and therefore is not subject to the withdrawal rules governing the mandatory balance. (Statutory legislative intent language does indicate that nearly half of the optional total—about $1.5 billion—would be subject to rules. The remainder of the optional balance—$1.6 billion—was deposited before the voters passed Proposition 2.) As such, under this argument, the Legislature could appropriate up to $3.1 billion from the BSA by majority vote and without a fiscal emergency declaration by the Governor.

State Can Access “Amount Needed to Cover Emergency.” In the case of a fiscal emergency, the Legislature may only withdraw the lesser of: (1) the amount needed to maintain General Fund spending at the highest level of the past three enacted budget acts, or (2) 50 percent of the BSA balance. Hypothetically, if resources available for 2019‑20 were expected to be lower than the enacted budget for 2019‑20 by $5 billion, then the Legislature could access that amount from the BSA. If the amount of the budget emergency in 2019‑20 exceeded half of the mandatory reserve balance (currently, $6.7 billion) then the Legislature could only access that lower amount. In this situation, however, the state also likely would face a budget emergency for 2020‑21. In that case, the state could—in one budget cycle—use up to half of the BSA balance to address the current-year budget problem and still have the option to use the remaining balance to address the budget problem for 2020‑21 as well.

School Reserves

Funding for K-12 education is the largest General Fund expenditure, representing about 40 percent of the state’s General Fund. Although individual school districts are responsible for adopting their local budgets, the Constitution requires the state to provide funding for schools and ensure K-12 education is available to all students. Moreover, California schools receive most of their funding from the state General Fund. These factors mean that the fiscal condition of school districts and the state are closely connected. A decline in state revenues—as the state is likely to experience in response to the COVID-19 emergency—is likely to reduce school funding. In this section, we analyze two sources of reserves that are available to mitigate some of this reduction. First, the state has a state-level reserve for schools (although as we will describe shortly, the balance in that account is very low). Second, school districts hold reserves in their local operating accounts.

State-Level School Reserve

State Has a Reserve Account Specifically for Schools. In addition to making rules for deposits into the BSA, Proposition 2 established a reserve account for schools. The Constitution requires the state to deposit funding into this reserve when school funding is growing relatively quickly and various other conditions are met. The reserve is intended to smooth out some of the volatility in funding to schools and community colleges. Unlike the BSA, which is available to support any program in the state budget, the state school reserve can only be used to support schools.

How Much Is in the State-Level School Reserve? Compared with the BSA, the rules regarding deposits into the school reserve are more restrictive. Whereas the state has accumulated a significant balance in the BSA over the past several years, the state did not make its first deposit into the school reserve until it enacted the 2019‑20 budget plan. That deposit was $377 million—representing less than 1 percent of state spending on schools in 2019‑20.

Local Reserves

What Reserves Do School Districts Have? Similar to the state, school districts hold reserves in their local operating accounts. Also similar to the state, districts can use some portion of these reserves to cover a higher expenditure level when revenues decline. Our analysis focuses on the portion of school reserves that have no legal restrictions on their use. We also exclude reserve data for community colleges, charter schools, county offices of education, and education-related joint powers authorities because the budgets of these entities often look much different than those of school districts.

How Do School Districts Use Reserves? Districts use reserves for a variety of purposes in addition to mitigating revenue volatility. This includes, for example, managing cash flow, addressing unexpected costs, and saving for large purchases. For example, regarding cash flow, while districts’ largest expense—salaries—is paid relatively evenly throughout the school year, districts receive revenue on a more uneven schedule. Property tax revenue, for example, arrives in two large installments (in December and April). Districts also save money for large, anticipated costs like replacing computers or unexpected costs like repairing a damaged roof. When districts are holding reserves to pay for specific future projects or activities, they usually earmark that portion of their reserves within their local budgets. Reserves intended to address economic uncertainty and unanticipated expenditures, by contrast, generally are not earmarked.

How Much in Reserves Do Schools Hold? At the end of the 2018‑19 fiscal year, districts held a total of $12.8 billion in unrestricted reserves. This level represents 17 percent of district spending in that year—enough to cover about two months of expenditures. The data indicate that $6.9 billion of this amount was earmarked for specific uses and $5.9 billion was not earmarked. Some, but not all, of this funding would be available for schools to maintain a higher expenditure level if revenues declined. Many school districts would need to retain a significant portion of the reserves held in cash, for example, to continue to properly manage cash flow. Moreover, drawing upon earmarked reserves could involve foregoing various future projects or activities that districts regard as high priorities.

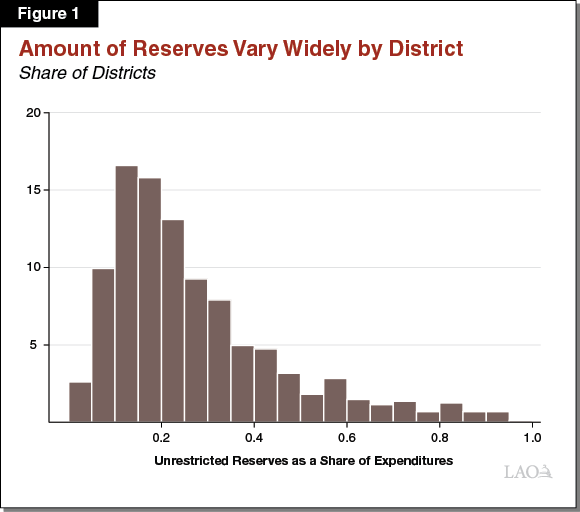

Reserve Levels Vary Widely by District. While district reserves average 17 percent of school spending statewide, significant variation exists at the district level. Figure 1 shows the variation in reserves as a share of expenditures. As the figure shows, the median district holds reserves equal to 22 percent of expenditures. At the lower end, about one-quarter of districts hold reserves equating to less than 14 percent of their expenditures. These districts likely would need to reduce spending quickly if their revenue were to decline. (Many districts, however, might find it difficult to reduce expenditures in a short time frame given their fixed costs and statutory requirements related to staff layoffs and the number of instructional days they must offer.) At the upper end, about one-quarter of districts hold reserves exceeding 35 percent of their expenditures. In these districts, the larger budget cushion could mitigate potential revenue reductions.

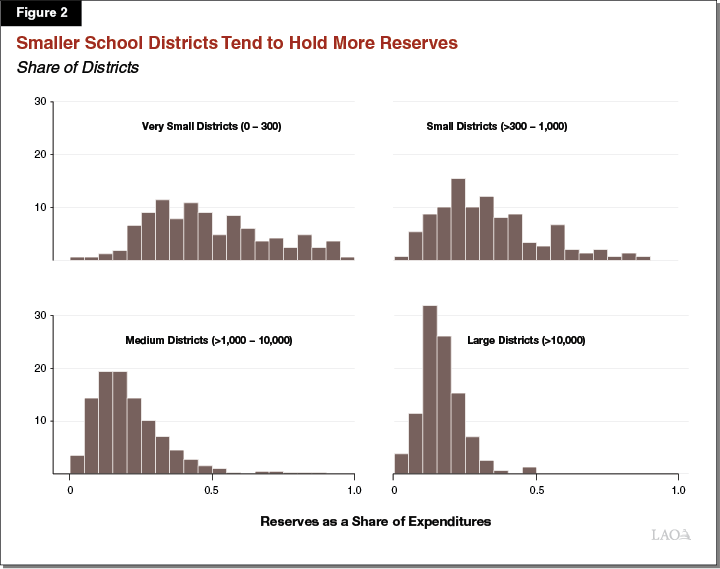

Smaller Districts Tend to Hold More Reserves. A strong relationship exists between district size and reserves. As Figure 2 shows, half of very small districts (those with fewer than 300 students) held reserves of more than 45 percent of expenditures. Large districts (those with 10,000 to 50,000 students) had median reserve levels equal to 16 percent of expenditures. One reason that small districts tend to hold more in reserves as a share of expenditures is that these reserve levels are still low in absolute terms. For example, a single major facility repair or other large cost might require a small district to deplete most of its reserves in a single year. The same repair, to a larger district, could be relatively small in percentage terms. Larger districts also typically face less difficulty managing cash flow.

Key Takeaways

State Reserves at Historic Level, but Likely Lower Than Discussed in January. Given economic decline due to the COVID-19 emergency, state revenues will be lower than estimated in January. Moreover, economic and budget conditions have evolved rapidly in recent weeks and are likely to continue to do so. Consequently, at this point, the most useful reference point for the state’s reserve level is the amount the state currently is holding in its reserve accounts—$17.5 billion. Compared to prior recessions, the state enters this period of economic uncertainty with significant reserves. That said, in the past, we have found that a budget problem associated with a typical recession could significantly exceed this sum. As such, the Legislature will want to consider carefully how to deploy these resources once more is known about the state revenue effects of this emergency.

Local School District Reserves Could Provide Short-Term Buffer, but State-Level School Reserve Minimal. Local school district reserves could provide many school districts with time to prepare for declines in revenues. Districts with larger reserves likely will have time to adjust their spending gradually, whereas districts with smaller reserves are likely to face difficult decisions more quickly. Regardless of their exact reserve level, however, few districts have enough to maintain current service levels for an extended period if revenues were to decline significantly. Moreover, the balance in the state-level school reserve is very small compared with the revenue declines schools might face. All of these factors suggest that state and school leaders should be very cautious as they prepare for the upcoming year.