LAO Contact

October 16, 2020

COVID‑19

DMV Shift to Online Services Due to COVID‑19

On March 26, 2020, the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) closed all of its 171 field offices due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19). As a result, DMV extended deadlines for expired learner permits, driver’s licenses, and identification (ID) cards; increased the capability of self-service kiosks across the state; and expanded the number of transactions available online. In this post, we focus on the department’s recent expansion of online services, including the creation of the Virtual Field Office, as well as potential fiscal and service implications of this expansion and other issues for legislative consideration as DMV continues to expand online services.

Californians Access DMV Services in Various Ways

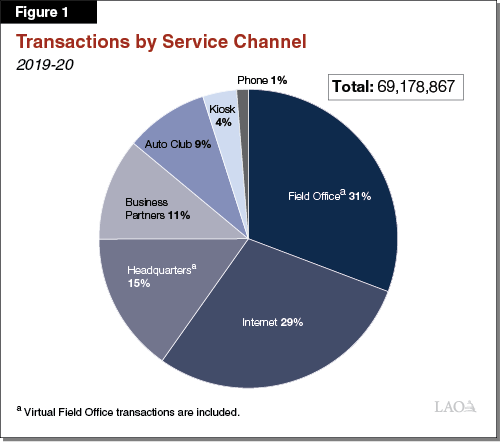

DMV Offers a Range of Services to the Public. In 2019‑20, DMV processed over 68 million transactions. Nearly half of the transactions were vehicle registration renewals. Other common transactions included driver’s license renewals and vehicle title transfers. Customers can access DMV services through multiple service channels, such as field offices, mail, online, self-service kiosks, auto clubs (such as the American Automobile Association), phone, and business partners (such as auto repair shops and car dealerships). As shown in Figure 1, in 2019‑20, nearly one-third of all transactions occurred in field offices and nearly another one-third were completed online.

Not all service channels are available for every type of transaction, and customer use of different service channels varies depending on the transaction. For example, in 2019‑20, vehicle registration renewals were most commonly completed online (37 percent) or by mail (20 percent), with only 13 percent done in field offices. In contrast, about 66 percent of driver’s license renewals and 84 percent of ID card renewals occurred in field offices. Although other service channels, such as online and mail, exist for driver’s license and ID card renewals, more than half of the customers currently need to go into the field office due to federal regulations for REAL ID. When customers are not required to renew their driver’s license at the field office, the majority complete their transaction online or by mail—only about one-quarter choose to go to the field office.

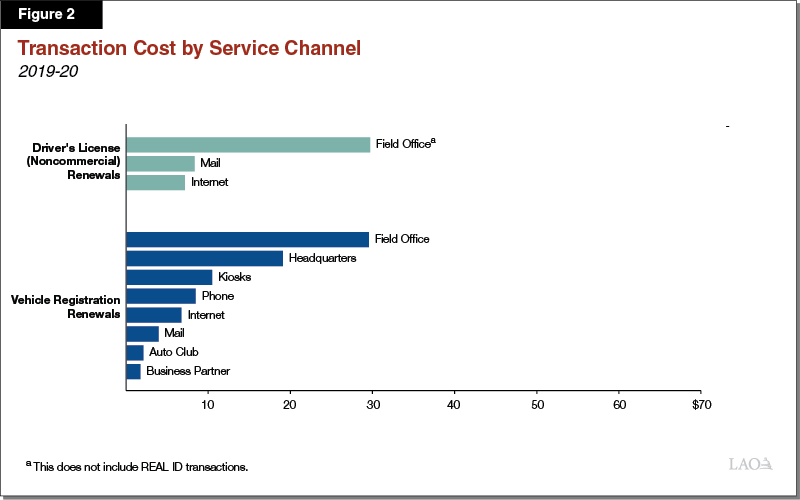

Transaction Costs Vary by Service Channel. Each service channel requires different levels of costs. Service channels that require more personnel, time, materials, or infrastructure are more expensive than others. For example, Figure 2 shows vehicle registration renewals and non-commercial driver’s license renewals completed at field offices are far more expensive than when completed through any other service channel. Field office transactions are comparatively expensive in part because of the costs to staff and maintain field offices, as well as the fact that field office transactions are less automated than alternatives, such as those conducted through mail, internet, or kiosks.

Status Update:

Shift to Online Services Due to COVID‑19

All Field Offices Closed Temporarily as a Result of the Pandemic. Growing concerns from employees and the public about COVID‑19 led the department to close all field offices on March 26, 2020. Some services that required an in-person visit became unavailable, such as behind-the-wheel drive tests. However, DMV expanded other services to be available online. In addition, the department implemented other measures to help customers, such as extending expiration dates for learner permits, driver’s licenses, and ID cards, as well as expanding the capability of kiosks across the state to accept additional types of transactions. On May 8, 2020, DMV began to re-open field offices limited to transactions that require an in-person visit, and all field offices reopened by June 11, 2020. As of September 2020, DMV field offices are serving customers that had scheduled their appointments prior to the field office closures and those that need to complete a transaction that requires an in-person visit. New appointments for services that do not require an in-person visit are not yet available. In addition, to protect the health and safety of employees and customers, the department has enacted precautionary measures, such as temperature checks, face covering requirements, and physical distancing protocols.

VFO Now Provides Some Services That Previously Required an In-Person Visit. During the field office closures, DMV expanded the types of transactions available online through the Virtual Field Office (VFO) on its website. At the VFO, customers can fill out online forms, upload the required documents, and receive follow up from DMV to complete the transaction. About 130 select field office and headquarter employees process transactions for the VFO on a daily basis, although the exact number of employees fluctuate depending on customer demand. The VFO offers nine transactions that previously required an in-person visit. (This is in addition to the 14 transactions customers already could complete online by themselves prior to the pandemic.) For example, customers can now transfer a vehicle title at the VFO, one of the most common transactions at the DMV. The department plans to continue adding more transactions to the VFO in the next several months. California is among many states that are trying to leverage online services due to COVID‑19. At least 31 states and the District of Columbia have rolled out different policies and programs aimed at encouraging greater use of online services and expanding the number of services offered online.

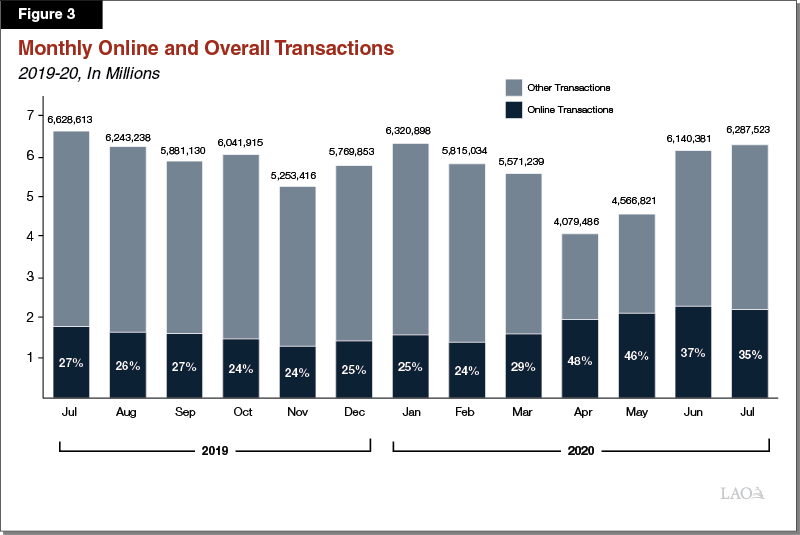

Use of Online Services Have Increased…As field offices closed in late March, self-service online transactions (not including VFO transactions) increasingly made up a larger portion of the total transactions processed by DMV. As shown in Figure 3, prior to the field office closures, online transactions made up about one-quarter of the department’s total monthly transactions. During the field office closures, self-service online transactions increased to make up nearly half of the monthly total transactions. In the two months since field offices fully reopened, total transactions have returned to pre-pandemic levels with over one-third of those transactions occurring online.

With the implementation of VFO, the department increased its capacity to process transactions virtually. Five of the nine transactions available require assistance from a DMV employee. The remaining transactions are processed by robotic process automation. As of September 1, DMV reported completing about 155,000 transactions that require employee assistance, as well as 425,000 transactions through robotic process automation.

…But Total Number of Transactions Is Lower Than Previous Year. As field offices began to re-open, the department’s monthly transactions through all service channels neared pre-closure levels. However, due to the decline in transactions in April and May 2020, the total number of transactions in 2019‑20 was lower than in the previous year. In 2019‑20, DMV processed a total of 68.3 million transactions, which was 1.9 million (3 percent) fewer than in 2018‑19. This total reduction in transactions is likely due to a combination of factors, including the closure of field offices and extension of renewal deadlines for driver’s licenses, ID cards, and learner permits.

Changes Have Potential to Make DMV More Efficient

Online Services Could Improve Customer Experience. An expansion of online services could benefit a range of DMV users. Some customers might find that online services provide more flexibility to complete transactions at a convenient time and without having to go into a field office. In particular, customers in more remote areas further away from a field office might prefer online services. Other customers who need or prefer to go to the field office could benefit indirectly from expanded online services, as well. This is because if more customers use online services instead of going to field offices, the decreased number of people at field offices could mean shorter wait times for the remaining customers. As field offices re-opened, the department’s June report to the Legislature showed that statewide average wait times for customers without appointments was less than half what it had been in the months preceding the pandemic. Multiple factors contributed to the decline in wait times. Greater use of online services likely reduced the number of people who went to field offices to conduct transactions, thereby reducing wait times for those who did go into the offices. In addition, DMV’s extension of renewal deadlines for learner permits, driver’s licenses, and ID cards likely decreased demand at field offices. However, after the initial decline in wait times, the department’s July report to the Legislature showed customers without appointments are waiting about the same time as in the months before the field office closures. This suggests that greater availability of online services alone does not necessarily reduce wait times, but can be one factor in contributing to a decline in wait times.

Greater Use of Online Services Could Reduce Some Cost Pressures on the Motor Vehicle Account (MVA). As mentioned previously, transaction costs vary across different service channels. If more transactions could be processed using less expensive channels, the department could provide more services with the same amount of resources. For example, although the majority of vehicle registration renewals are completed outside of field offices, vehicle registration renewals still make up about 18 percent of all transaction completed in field offices even though all vehicle registration renewals can now be completed in other service channels. Shifting more field office transactions to less expensive service channels could lead to significant efficiency improvements. In the short term, this could mean greater staff capacity to process transactions in field offices, which would be beneficial as more customers need to visit a field office to secure their REAL ID by October 2021. (Federal law requires an in-person visit for REAL ID.) In the longer term, a sustained shift to online services could reduce staffing needs and costs. For example, based on the average cost of transactions, we estimate that if half of the vehicle registration renewals currently completed by field offices are instead done online, that could save up to about $40 million annually.

DMV has 171 field offices across the state, 96 of which are state owned and 75 are leased. There are services, such as REAL ID and behind-the-wheel tests, that cannot be conducted online. As such, it is important that all Californians have access to a field office to process DMV transactions. However, if more customers use online services (and other less expensive service channels), DMV could reduce the size of or consolidate field offices. Doing so would have the potential to reduce costs associated with leasing, building, and maintaining facilities. Many DMV field offices are aging and in need of replacement or renovation. DMV reports that its field offices are, on average, 36 years old, and 23 offices it uses are 50 years or older. A change in approach to the size and number of field offices could have immediate impact on capital outlay planning and construction in the next several years. It costs roughly $20 million dollars to plan, design, and construct one new DMV field office.

Decreasing the size of field offices, consolidating multiple field offices, and reducing staffing levels could reduce costs and relieve some cost pressures on the MVA, the primary fund source for the DMV. These fiscal savings could be important due to the structural deficit of the MVA. A decrease in costs could be a unique opportunity to reduce the reoccurring fiscal pressures on the fund. In recent years, the expenditures have steadily outpaced the revenues in the MVA, including a projected operational shortfall of $59 million in 2020‑21. The administration projects that the fund will become insolvent by 2022‑23.

However, Online Access Concerns Remain. Although an expansion of online services could provide benefits to some customers, not all Californians stand to benefit as much. For example, about one-quarter of all California households do not have broadband subscriptions at home. African American, Latino, low income, and rural households, as well as households without a college education, are disproportionately less likely to have broadband service at home. For these customers, online DMV services remain less accessible, and, therefore, they are more likely to depend on other service channels. In addition, some customers might feel uncomfortable processing DMV transactions online because many transactions require uploading documents that include sensitive information, such as social security numbers. Other customers might prefer to pay with cash instead of a credit card. These issues highlight the importance of ensuring that customers have a variety of service channels available even while the state seeks to expand the use of online services.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

COVID-19 accelerated customer use of online services out of necessity, and it is too early to tell whether this will result in a more permanent shift in how customers access the DMV. A sustained shift to online services could be beneficial to the state in multiple ways, including improving customer service, as well as near- and longer-term fiscal savings. To ensure these potential benefits are achieved—as well as ensure that potential access challenges are mitigated—the Legislature could provide oversight into the use of online services at the DMV. Some areas and questions for future legislative oversight include:

- Implementation Progress. How well is the DMV implementing the expansion of online services? Are there additional services that could be made available online? What are the trends in how frequently customers are using online and VFO services even after field offices have re-opened? How is the department tracking and assessing the transactions completed through the VFO? What changes could DMV make to further improve its new services? What operational challenges has the department encountered as it expands online services? What additional costs is DMV experiencing—such as for software and hardware upgrades—in order to implement increased online services? How does the expansion of online services fit with the other efforts by the department to modernize legacy information technology (IT) systems?

- Customer Experience. What are the findings from DMV customer service surveys for both in-office and online services? Do users of the VFO rate the new system as convenient and easy to use? How have wait times changed at their field offices as more online services are introduced? What steps has DMV taken to ensure that individuals without broadband access can still access DMV services? What effort is the department undertaking to encourage customers to use online services?

- Near-Term Savings. To what extent does increased use of online services increase DMV efficiency? For example, is the department better able to manage increases in REAL ID workload in coming months? Has the department considered modifying its fee structure or other actions to incentivize more customers to use less expensive service channels? For example, has it considered offering discounted fees for online transaction, similar to other states like Georgia, Massachusetts, New Mexico, and Virginia? How could such an option be structured to (1) incentivize sustained shifts to online services, (2) reasonably reflect actual costs, (3) prevent a net loss in MVA revenues, and (4) ensure Californians’ access to the DMV?

- Longer-Term Savings. What are the potential longer-term savings associated with an expansion of online services? How is the shift to online services informing the department’s estimates of future staffing needs, such as for those in field offices, managing IT systems, and processing online transactions? How is DMV reevaluating its capital outlay plans for updating and replacing field offices in light of what it is learning as it offers more online services? What are the implications of these changes on the fund condition of the MVA?