LAO Contacts

November 16, 2020

Update on School District Budgets

This post provides an update on the fiscal condition of California’s school districts as the state begins the process for developing its 2021‑22 budget. The first section provides background on the school district budget process and how changes in the state’s budget situation affected school districts’ planning for 2020‑21. The second section briefly describes our methodology for estimating statewide trends in school district budgets, while the third section describes our findings regarding school districts’ updated 2020‑21 budgets and expenditure projections through 2022‑23.

Background

School District Budgeting Is Shaped by State Budget Time Lines. State law requires the local governing board of a school district to adopt a budget by July 1 each year—about two weeks after the Legislature’s constitutional deadline to pass a budget bill. Since most school funding comes from the state, districts typically monitor each step in the state budget process, starting with the Governor’s January budget proposal for the coming fiscal year. The proposals at the state level affect the specific actions that districts will propose to do locally.

School Districts Usually Base Their Adopted Budgets on May Revision. To meet their July 1 deadline, districts usually adopt their budgets in a governing board meeting in early or mid-June. Since the state budget process is occurring concurrently, school districts are not typically able to incorporate the state’s final budget package into their adopted budgets. Instead, school districts typically use the funding levels proposed in the Governor’s May Revision. The school district's budget must be reviewed by its county office of education (COE) by August 15. The main objective of the COE is to determine whether the budget allows the school district to meet its financial obligations during the fiscal year.

School Districts Revise Their Budgets Throughout the Fiscal Year. School districts have several opportunities throughout a given fiscal year to provide updated budget information to their COE and the public. The first such opportunity is known as the 45-day revision, and it allows districts to revise their revenues and expenditures based on the enacted state budget. School districts also are required to provide COEs with an updated financial report at two points in the middle of the year. These are known as the first interim and second interim reports. For first interim, districts must submit by December 15 updated financial data as of October 31. For second interim, districts must submit by March 15 updated financial data as of January 31. The adopted budgets and interim reports must include revenue and expenditure estimates for the current year and two subsequent fiscal years.

General Fund Reserves Are a Key Measure of Fiscal Health. In California, General Fund reserves are a key component of the state’s system for overseeing school districts’ fiscal condition. In particular, COEs monitor districts’ unrestricted General Fund reserves—funds that are not restricted or earmarked for a specific purpose—as a percentage of annual General Fund expenditures. In addition, state regulations specify minimum reserve levels the state expects districts to maintain. These range from at least 1 percent to 5 percent depending on the size of the district (smaller districts having higher reserve requirements).

School Districts Face a Different Fiscal Situation Than Earlier This Year. Over the past year, school districts have seen significant fluctuation in their near-term fiscal outlook due to additional costs related to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) emergency and changes in the state’s budget outlook. Districts incurred higher costs in 2019‑20 to purchase technology necessary for distance learning and personal protective equipment in anticipation of schools reopening. (The state provided $100 million in one-time funding for this purpose in March 2020.) Districts’ expectations for funding in 2020‑21 also have fluctuated. In January 2020, the Governor proposed $3.7 billion in new funding for school districts, including $1.2 billion to provide a cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) for the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). In his May Revision, the Governor withdrew most of his proposed augmentations and proposed to reduce LCFF by $6.5 billion—equivalent to a 7.7 percent year-over-year reduction in rates.

Enacted Budget Avoids Reductions, Provides Schools Additional Fiscal Relief. The final budget package for 2020‑21, however, largely avoids K-12 education reductions by relying on $11 billion in K-12 education payment deferrals. The enacted budget also includes several provisions that provide fiscal relief to school districts. Most notably, the budget includes $6.8 billion in one-time funding—primarily federal funds—to assist school districts in addressing various issues caused by the COVID-19 emergency. Most of these funds must be spent by December 30, 2020. In addition, the budget package reduced school and community college pension contribution rates by approximately 2.2 percentage points in 2020‑21 and 2021‑22.

Districts’ Multiyear Projections Generally Assume Current Policies and Practices. When adopting their budgets, school districts are also required to make projections of their revenues and expenditures for the subsequent two fiscal years. In developing their multi-year projections, districts typically do not make assumptions about future actions of the governing board, but rather assume current policies remain in place. These multiyear projections allow districts and COEs to monitor the longer-term fiscal health of districts and determine whether the district would need to take budget action to remain solvent.

Methodology for Estimating District Budget Trends

We Used a Representative Sample of Districts to Make Statewide Projections. Although school districts regularly provide updates of their budget to COEs and the public, the state typically does not have aggregated financial information for all school districts until nine months after the end of the fiscal year. To have an earlier sense of district spending for 2019‑20 and their 2020‑21 outlook, we collected 2020‑21 budget documents from a representative sample of 95 school districts and made various calculations to estimate the statewide trends. This data includes updated estimates for 2019‑20 and projections of revenues and expenditures from 2020‑21 through 2022‑23. To provide context for our statewide estimates, we also collected historical data from 2015‑16 through 2018‑19. The district reserve data in this report focuses specifically on districts’ General Fund accounts, as well as another account known as the Special Fund for Other Than Capital Outlay, which districts also use to plan for fiscal uncertainty. Throughout this report, all references to the General Fund account are inclusive of this special account.

Findings

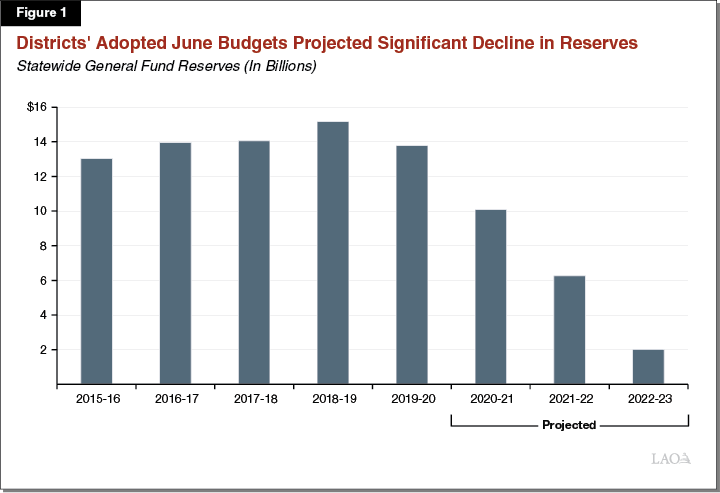

Most Districts Planned to Accommodate an LCFF Reduction by Spending Down Their Reserves. The majority of districts in our sample assumed a 7.7 percent reduction to LCFF in their 2020‑21 budgets adopted in June—consistent with the Governor’s May Revision proposal—and did not assume any COLAs in the subsequent two fiscal years. Throughout the multiyear period, districts largely held their expenditures flat and assumed they would use reserves to cover the budget shortfalls. As Figure 1 shows, statewide General Fund reserves would fall from $13.8 billion in 2019‑20 to $2 billion by 2022‑23 based on these assumptions. Many districts projected having negative ending fund balances by 2022‑23, suggesting that districts would have to make significant reductions to balance their budgets if the LCFF reductions had taken effect.

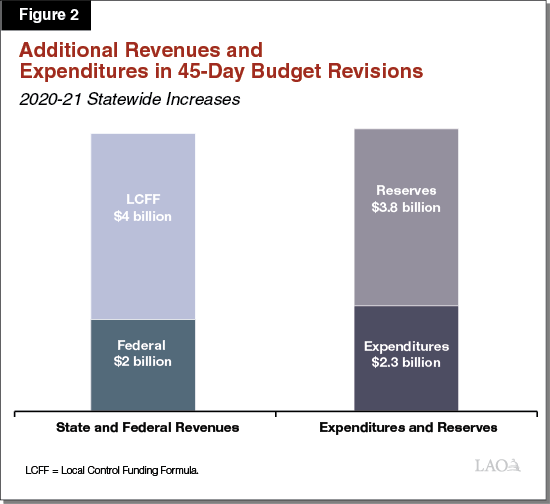

Most Districts Submitted 45-Day Revisions to Their Adopted Budgets. About four in five districts in our sample made use of the 45-day revision provision to provide updated budget information to their COEs. Figure 2 shows the changes in revenues and expenditures as a result of the 45-day revisions. These increases are primarily due to districts receiving higher LCFF funding and one-time federal funding than what was assumed in the May Revision. Generally speaking, districts did not increase expenditures in their 45-day revisions as a result of the LCFF restoration and instead deposited the funding into their reserves. (For purposes of our calculations, we assumed the one in five districts that did not have a 45-day revision also restored the LCFF cut and deposited these funds to their reserves.) School districts are not required to update their multiyear projections when they submit 45-day budget revisions. As a result, we were unable to update districts’ multiyear projections to reflect updated LCFF revenues.

Most Adopted District Budgets Did Not Fully Incorporate One-Time Federal Funds. Most districts in our sample either did not incorporate one-time federal funds into their adopted June budgets or had placeholder estimates that differed notably from districts’ actual allocations. This is likely because detail regarding how funds would be allocated was not yet available in June. Although many districts updated these revenue estimates as part of their 45-day revision, a small portion continued to assume no one-time federal funding. As a result, our statewide estimates of one-time revenues and expenditures are likely an underestimate.

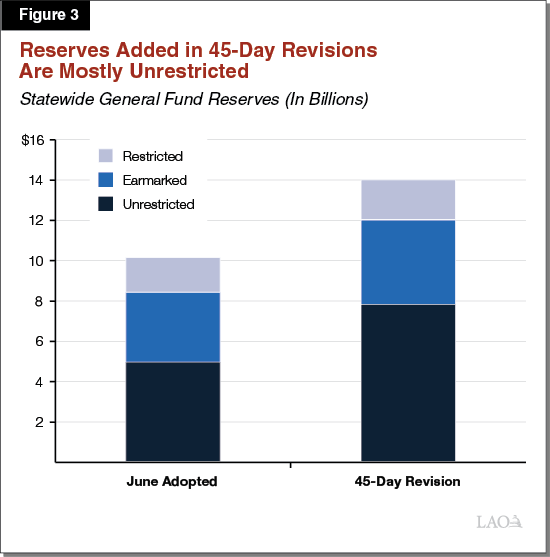

Most of the Increase in District Reserves Is Unrestricted. We estimate districts’ projected reserves at the end of 2020‑21 increased by $3.6 billion as a result of the 45-day budget revisions. As Figure 3 shows, the vast majority of the increase ($2.9 billion) is unrestricted. Having a larger amount of unrestricted reserves provides districts with more flexibility to address the fiscal uncertainty created by the COVID-19 emergency. School districts’ restricted reserves—funds subject to constraints by state or federal law—did not change in their 45-day revisions.

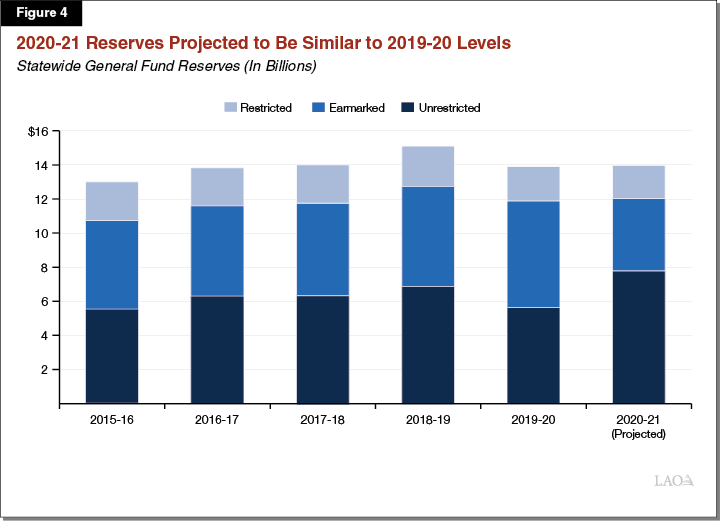

Districts’ 2020‑21 Reserves Now Appear to Be Restored to 2019‑20 Levels. After incorporating districts’ 45-day revisions, we project total statewide General Fund reserves to be $14 billion in 2020‑21—similar to 2019‑20 levels. (See Figure 4.) This is equivalent to roughly 19 percent of school district General Fund expenditures in 2020‑21. Reserve levels can range significantly by district. Within our sample of 95 districts, for example, reserve levels ranged from 2 percent to 43 percent.

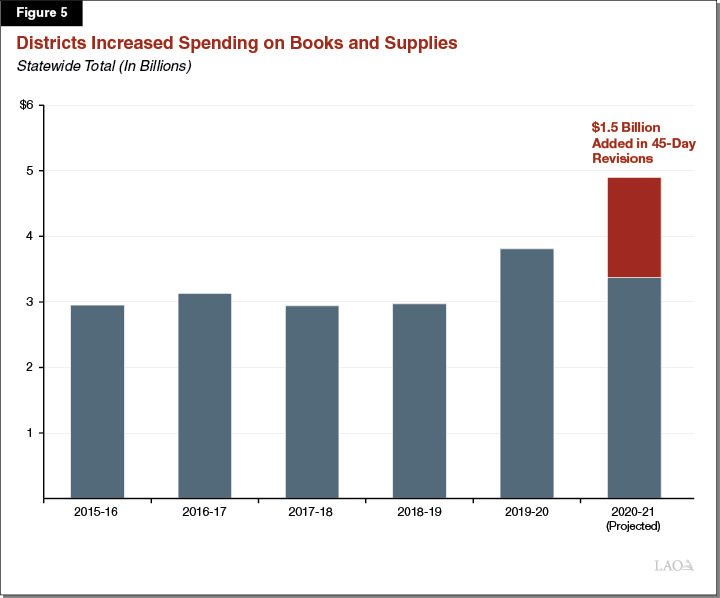

Districts Spending Significantly More on Books and Supplies in 2019‑20 and 2020‑21. As Figure 5 shows, districts spent $3.8 billion on books and supplies in 2019‑20—$838 million higher than the previous year. This increase is likely due to the costs of additional technology associated with distance learning and the personal protective equipment needed for reopening schools. As Figure 5 shows, districts project spending $4.9 billion on books and supplies in 2020‑21. Of this amount, $1.5 billion represents new spending added in districts’ 45-day revisions. This is likely due to one-time federal funding districts had not included in their adopted June budgets.

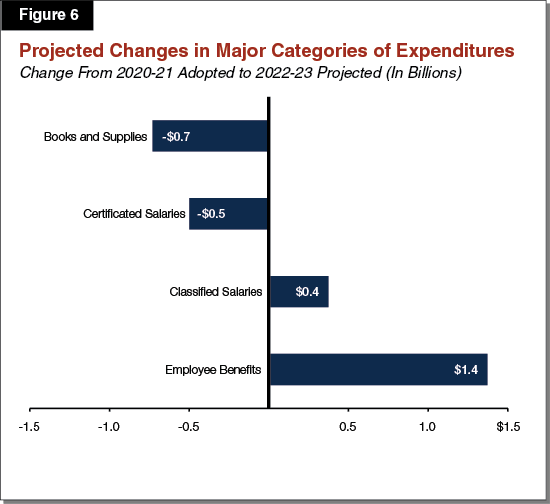

In Out-Years, School Districts Project Increases in Classified Salaries and Employee Benefits. Figure 6 shows projected changes in district spending from 2020‑21 to 2022‑23 in several major expenditure categories. Districts project the largest increases ($1.4 billion) in employee benefits. This includes the additional costs of providing employee health benefits and higher district contribution rates for the California State Teachers’ Retirement System and California Public Employees’ Retirement System. (The temporary reduction in pension contribution rates ends in 2021‑22.) Districts also project modest increases in spending for classified employees (including instructional aides, clerical staff, and custodians). School districts project a decrease in spending on certificated salaries (including teachers, administrators, and counselors). This reduction is likely because districts project hiring fewer certificated employees as student attendance declines.

Conclusion

Despite significant fiscal uncertainty, district budgets have stayed generally stable this year. The state budget largely avoids reductions to schools and provides fiscal relief through one-time federal funding and lower pension contribution rates. In future years, however, these fiscal supports will recede and districts will be left with pension and health benefit costs ratcheting higher on the one hand and reduced funding growth—a consequence of declining student attendance—on the other. In the coming years, the level of state funding for schools will be a key factor affecting how school districts adapt to these cost pressures. Within the next few days, we plan to release our fall fiscal outlook, which will provide our projections of school funding over the next several years.