LAO Contact

December 18, 2020

California Community Colleges—Managing Cash in a Time of State Payment Deferrals

Summary

Districts Began Preparing for State Payment Deferrals Several Months Ago. To generate one‑time state savings, the 2020‑21 budget package deferred $1.5 billion in state payments to the California Community Colleges (CCC) until 2021‑22. (The budget package also deferred $11 billion in state payments to school districts until 2021‑22.) Specifically, the state is scheduled not to make certain payments to the community colleges from February 2021 through June 2021, with payments instead being provided over the July 2021 through November 2021 period. Districts are planning to handle these deferrals by using various cash management strategies, including tapping their local reserves and borrowing externally from investors. We estimate about one‑third of CCC districts are planning to borrow externally. Although districts indicate deferrals are a major challenge, they generally believe them to be manageable this year.

Given Improved State Revenue Situation, Legislature Could Eliminate Some or All Deferrals. In our November 2020 fiscal outlook reports, we show that the state’s budget situation has improved considerably compared with June 2020 estimates. State revenue estimates have been revised upward, as have estimates of school and community college funding requirements. Particularly due to upward revisions for 2019‑20 and 2020‑21, we estimate that the state has a significant amount of one‑time settle‑up funds to spend on schools and colleges, though the exact amount will not be known for several more months as additional budget data becomes available. We recommend the Legislature place a high priority on using these one‑time funds to eliminate the K‑14 deferrals. Even under our lower‑end Proposition 98 estimates, the state could retire some of the K‑14 deferrals. At roughly the midpoint of our Proposition 98 estimates, the state could eliminate all of the K‑14 deferrals.

Legislature Has Options Regarding Timing. Should the Legislature decide to rescind some or all of the K‑14 deferrals, it could (1) do so through immediate midyear action or (2) wait and rescind as part of the 2021‑22 budget package. Under the first option, we encourage the Legislature to first rescind the February through April 2021 deferrals (totaling $7.2 billion in additional Proposition 98 spending), then reassess state revenues in April to determine whether to retain or rescind the May and June deferrals. The second option represents a more cautious approach. The first option provides greatest benefit to those community college districts relying on their local reserves whereas the second option tends to provide greatest benefit to those districts relying on external borrowing from investors (as these districts would receive borrowed funds upfront that could be invested until needed). If the Legislature decides to keep any deferrals in place for 2020‑21, it could revisit the repayment schedule, potentially paying off all the deferrals in July 2021 rather than extending repayments through November 2021. The Legislature could make these repayment decisions as part of budget close‑out in spring 2021.

Introduction

To help address the state’s large budget deficit as estimated in June 2020, the 2020‑21 budget package deferred a substantial amount of General Fund payments to schools and community colleges. In this post, we (1) provide background on community college cash flow and cash management, (2) describe the community college deferrals included in the state’s 2020‑21 budget package, (3) explain how the CCC Chancellor’s Office is implementing these deferrals, (4) discuss how community college districts are responding, and (5) present options for the Legislature to consider, particularly given the improved budget outlook.

Cash Flow and Cash Management

Cash Position Fluctuates Throughout the Year. A district’s cash position reflects how much cash (assets that are available to spend immediately) it has at any given point in time, based on when it incurs expenses and receives revenue. A district’s expenditures (the largest of which is employee salaries) are generally even throughout the year. The largest revenue source for most districts—state General Fund—is generally aligned with the timing of expenditures. Districts receive state General Fund allocations in monthly installments, with 8 percent of their total allocations provided in most months. The next largest revenue source for most districts—local property tax—typically arrives twice per year (in December and April), though arrangements vary somewhat by county, with some counties providing more installments per year.

Districts’ Cash Positions Throughout the Year Depend Partly on Mix of Revenue Sources. Districts vary widely in terms of their reliance on state General Fund and local property tax revenue. In 2019‑20, 10 of CCC’s 72 locally governed districts received 85 percent or more of their apportionment funding (general purpose monies) from the state General Fund. At the other end of the spectrum, nine districts received 85 percent or more of their apportionment funding from local property tax revenue. (In 2019‑20, seven of these nine districts were “excess tax” districts, meaning their local property tax revenue exceeded the entire amount they were entitled to receive under the main community college funding formula.) A district’s cash position can vary as a result of its reliance on certain fund sources and the timing of associated receipts. Depending upon a district’s exact mix of state and local funding and its specific costs in any given month, a district may have more expenditures than revenues (resulting in a negative cash position or cash deficit) or more revenues than expenditures (resulting in a positive cash position or cash surplus).

To Manage Cash Flow, Districts May Use Reserves and Internal Borrowing. Each district maintains a primary account (referred to as its “general fund”) for most operating expenses. It also maintains separate restricted accounts for certain activities that have special rules, such as facility projects, categorical programs, and auxiliary enterprises (including parking and health services). When faced with a cash deficit, districts can draw down reserves held in their primary operating account. Statute also allows districts to borrow from other accounts to manage their cash position. Unlike with schools, statute does not place limits on the amount that community colleges can borrow internally or the duration of these loans.

Districts May Also Borrow From External Sources. Districts prefer to use reserves and interfund borrowing to manage cash, as these options are no‑cost or low‑cost and administratively simple to use. If these options are not sufficient to generate needed cash, districts can turn to external options. One external borrowing option available to districts is issuing tax and revenue anticipation notes (TRANs). Investors purchase TRANs, and districts pay them back with interest, typically within 13 months of issuance. Because each TRAN has issuance costs (including legal fees and transaction fees), districts commonly form groups (or pools) to sell the notes. Historically, several organizations have administered TRAN programs for community colleges, including the Community College League of California (an association representing CCC trustees and chief executive officers) and the California School Boards Association (which allows colleges to pool together with schools). In addition to borrowing from private investors, community college districts are permitted to borrow from county treasurers and county offices of education. In these cases, districts typically are charged the same interest rate for the borrowed cash as what the county agency would have earned had it retained the cash in a short‑term investment account. The availability of county borrowing options varies, partly because county agencies face their own cash flow issues.

In Previous Recessions, State Deferred Payments to CCC. In past recessions, the state has authorized some college spending in one fiscal year but not provided the associated cash until the following fiscal year. These payment deferrals have allowed districts to maintain their programs—provided they can access the cash to cover associated expenditures while awaiting state funds. The state began using payment deferrals during the dot‑com bust but relied much more heavily on them during the Great Recession. The practice of deferring college payments peaked in 2011‑12, when the state deferred a total of $961 million in CCC payments—accounting for nearly 30 percent of CCC Proposition 98 General Fund support. When these deferrals were in effect, districts received state payments several months late, leading districts to have unusually large cash deficits.

Districts Relied on TRANs to Handle Deferrals During the Last Recession. During the Great Recession, a few districts had sufficient reserves and internal borrowing options to weather the deferrals without turning to external borrowing. Most districts, however, relied on TRANs to secure enough cash to meet their expenditure commitments while awaiting state payments. As with all TRANs, these TRANs came with issuance and interest costs that districts had to pay until they no longer needed to use the notes for cash flow purposes. Buoyed by a recovering economy and increased revenue from a tax increase on high‑income earners (Proposition 30, approved in 2012), the state eliminated all of these deferrals by the end of 2014‑15—generally negating districts’ continued need to use TRANs to manage their cash flow.

Recent State Budget Actions

Budget Package Relied on New Round of Deferrals. Proposition 98 constitutionally governs the minimum amount of funding provided to schools and community colleges each year. In June 2020, the state estimated that the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee had dropped notably for both 2019‑20 and 2020‑21 relative to assumptions it had made one year earlier (in June 2019), prior to the pandemic. To adjust to the lower 2019‑20 minimum guarantee, the revised 2019‑20 budget included $330 million in CCC deferrals (and $1.9 billion in deferrals for schools). For 2020‑21, the Legislature rejected the Governor’s May Revision proposal to reduce Proposition 98 spending for community colleges through a combination of deferrals and spending cuts. Instead, the final budget relied almost exclusively on deferrals. Specifically, the 2020‑21 budget maintained the 2019‑20 deferrals and added another $1.1 billion in CCC payment deferrals from 2020‑21 to 2021‑22. (It also deferred $9.2 billion in state payments for schools—for a total of $10.3 billion in K‑14 deferrals.) Combined, $1.5 billion in Proposition 98 funds intended for community colleges in 2020‑21 is not scheduled to be paid until the first half of the next fiscal year. (Under the 2020‑21 budget package, $791 million of the $1.5 billion was to be rescinded if the state received additional federal relief funding by October 15, 2020, but no such funding was received by that date.) In the box below, we discuss the potential limit to additional deferrals were the state budget to deteriorate significantly over the next couple of years.

The Limits of Deferrals

When we began researching this summer how community colleges were responding to the latest round of Proposition 98 payment deferrals, many budget makers were wondering whether the state would need to enact additional deferrals in 2021‑22. Since this summer, the state’s budget outlook has improved considerably. The very large difference between the June 2020 and November 2020 revenue estimates, however, reflects the greater uncertainty the state is facing due to the pandemic. Were the state to see another large swing, but in the negative rather than positive direction, it might find itself once again contemplating Proposition 98 payment deferrals. Below, we identify several issues for the Legislature to consider were additional deferrals to be pursued in the future.

Likely a Practical Limit to Additional Deferrals. As deferrals mount, the borrowing burden on schools and colleges increases. Typically, once the state is deferring several months of payments, many districts, especially those with low reserve levels, must turn to external borrowing. These districts incur issuance and interest costs to maintain their programs as long as the deferrals remain in effect. In advance of issuing tax and revenue anticipation notes (TRANs), districts need time to prepare several documents, including a cash flow analysis. Districts tend to need three to four months advance notice to complete all the steps entailed before receiving TRANs proceeds. Taking into account these factors, we think the state likely could defer no more than about eight months of Proposition 98 payments before districts encountered administrative obstacles.

Some Investors’ Appetite for TRANs Is Limited. As deferrals mount, TRANs also can become less attractive to investors. For example, the state deferring eight months of Proposition 98 payments could signal that its reserve levels had shrunk and its fiscal management had worsened, with ripple effects for schools and colleges. At this point, some investors might get out of the TRANs market and decide to turn to safer, more promising short‑term investment options. While some investors might remain in the TRANs market, the interest cost that districts incurred for TRANs likely would increase. Though these costs are historically low today, they could be higher the next time the Legislature adopts new deferrals.

Deferrals Impose Challenge for Budget Moving Forward. Deferrals allow the state to generate one‑time savings while allowing districts to sustain program spending for one year. As deferrals mount, being able to fill the gap between program spending and funding becomes less likely. If revenues and the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee do not grow enough the following year to fill the funding gap, program cuts or other budget solutions such as tax increases are required. In this situation, the deferrals give only a one‑year reprieve from program cuts, with cuts delayed but likely not avoided. Moreover, having to double‑up payments in the future to eliminate deferrals and get payments back on schedule comes at the expense of other budget priorities. Effectively, the state at that time is having to use available funds to support programs that districts already have provided rather than supporting new or expanded programs. As deferrals mount, future budget options thus become less attractive.

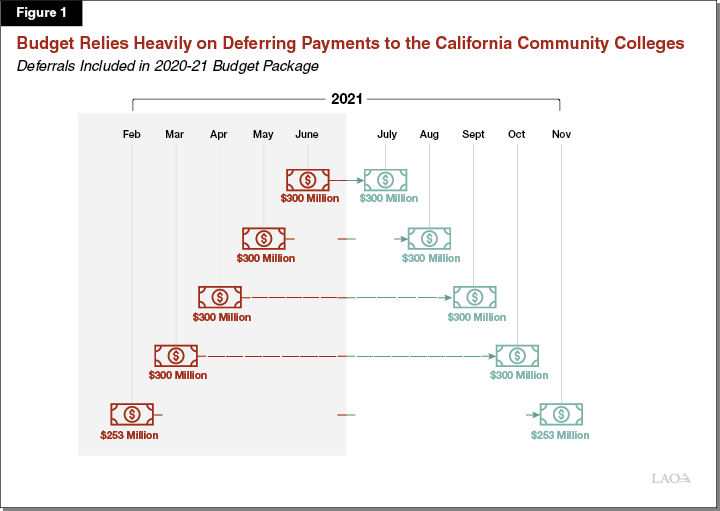

Districts to Experience a Series of Late Payments. Trailer language contains the exact amounts and timing of the newly instituted deferrals (Figure 1). Deferrals are to start in February 2021. For the February deferrals, districts are scheduled to wait nine months (until November) to receive their payments. Regarding which programs to pay late, provisional language directs the Chancellor’s Office to defer districts’ apportionment payments, and, if necessary, categorical program payments. Given the deferrals authorized in 2020‑21, the state will pay only about 75 percent of Proposition 98 General Fund to colleges on time. In effect, the state is set to send a large amount of cash to districts in 2021‑22 for programs they will have already operated in 2020‑21.

Budget Includes Deferral Exemption. Trailer legislation permits the state to exempt a community college district from deferrals if it meets certain financial hardship criteria. The qualifying criteria for such an exemption are the same as those used to qualify a district for an emergency loan from the state—generally that a district would otherwise be unable to meet its payroll expenses. Districts seeking an exemption must submit an application to the Chancellor’s Office at least two months in advance of the scheduled deferral. Trailer language allows the state to provide a total of up to $30 million per month in exemptions (up to $60 million under certain circumstances). By August 1, 2021, the Chancellor’s Office must notify the Joint Legislative Budget Committee of the districts requesting and receiving exemptions for 2020‑21.

Implementation of Deferrals

Apportionment and Some Categorical Payments Are Being Deferred. To comply with the deferral amounts and months specified in the 2020‑21 budget package, the Chancellor’s Office plans to make no apportionment payments to districts from February through June 2021 (unless a district receives a deferral exemption). This action results in a total of $1.1 billion in payment deferrals. To achieve the statutorily required $1.5 billion in deferrals, the Chancellor’s Office is also deferring to 2021‑22 just over $400 million in payments from a categorical program (the Student Equity and Achievement Program). The Chancellor’s Office selected this program as it is the largest categorical program whose funds are allocated primarily based on enrollment. As a result, deferring associated program payments impact districts more or less proportionally. (In an effort to improve districts’ cash position, the Chancellor’s Office is using its administrative flexibility to provide about $300 million in certain other categorical program funds to districts earlier than otherwise—in the first half rather than the latter half of 2020‑21, as normally would be the case.)

Chancellor’s Office Is Spreading Impact Across All Districts. In making apportionment payments from July 2020 through January 2021 (a total of $1.6 billion in payments), the Chancellor’s Office is using an approach designed to even out the impact of the deferrals among districts. Specifically, the Chancellor’s Office intends to minimize what would otherwise be a disproportionate impact of the deferrals on districts that rely heavily on state funding. Under the Chancellor’s Office’s methodology, each district is to receive at least 83 percent of its total apportionment amount—from local and state sources combined. If a district receives more than this resulting apportionment amount entirely from local sources, it will not receive any state apportionment payments in 2020‑21. (All districts will reach 100 percent of their total 2020‑21 apportionment amounts once the last deferred payment has been made in 2021‑22.)

Chancellor’s Office Has Created an Application for Hardship Exemption. In October, the Chancellor’s Office released a form and instructions on how districts can request a deferral exemption. The process requires a district to submit a cash flow projection showing that it cannot meet its financial obligations without an exemption from one or more of the upcoming deferrals. In reflecting available resources, the projection is to include the district’s revenues, unrestricted reserves, and the availability of any funds accessed through TRANs or other loans (including interfund borrowing). The first application—a request for an exemption from the February 2021 deferral—was due to the Chancellor’s Office by December 1, 2020. The Chancellor’s Office did not receive any first‑round applications. The second application—a request for an exemption from the March 2021 deferral—is due to the Chancellor’s Office by January 1, 2021.

District Responses

Districts Using a Variety of Means to Handle Deferrals. Throughout summer and fall 2020, we contacted more than two dozen community college districts to learn how they were responding to the newly instituted deferrals. The districts we contacted varied by size, geographic location, reserve levels, and reliance on General Fund for their apportionment payments. We also spoke with the Chancellor’s Office for a broader systemwide perspective. Although several districts cited deferrals as the greatest financial challenge facing them this year, none of the districts we heard from said the deferrals were unmanageable. Districts indicated they are planning to use a combination of both internal and external sources to manage cash in 2020‑21.

Many Districts Have Applied for a TRAN… Districts indicated they prefer to use internal sources to manage their cash to avoid the time and cost of external options. Due to the size of the scheduled deferrals, though, a number of districts we heard from indicated they were seeking a TRAN. Districts have several TRANs programs to choose from this time, including longer‑established programs offered by the Community College League of California and California School Boards Association, as well as new programs created by the California School Finance Authority (a unit of the State Treasurer’s office) and the Foundation for California Community Colleges (the official nonprofit auxiliary of the Chancellor’s Office). For most of these TRANs programs, districts had until October or November 2020 to apply for the first issuance. Based on our discussions with these programs, we estimate that about one‑third of CCC districts—a mix of small, medium, and large districts—applied for a TRAN in this first round. Currently, the programs are in the process of working with these districts to analyze their cash flows to help determine the appropriate amount of TRANs to issue. The programs indicate they may offer subsequent application rounds in the first few months of 2021.

…And Can Expect Relatively Low Costs of Borrowing. According to TRAN program staff we contacted, borrowing costs for districts are expected to be very low. Based on current market conditions, interest rates are less than half of 1 percent. Rates are so low that districts will likely have an opportunity to generate short‑term investment earnings that can fully offset their costs of borrowing. This is because districts receive all their TRAN proceeds upfront. In turn, they typically invest these proceeds in county investment pools until they need the cash to cover monthly operating costs. Currently, county investment pools generally are earning more than half of 1 percent. In some cases, county investment pools are earning more than 1.5 percent—well above typical borrowing costs for TRANs.

County Options Seen as Less Viable by Districts. In on our conversations with districts, a couple indicated they are seeking a loan from their county treasurer. Most districts, however, do not see this as a viable option, explaining that (1) their county prefers to provide loans only within a fiscal year, not across fiscal years; (2) they may have to compete for county loans with school districts, which also are subject to deferrals in 2020‑21; and (3) some counties appear to be facing their own cash challenges due to wildfires and coronavirus disease 2019‑related costs. No district we heard from was reaching out to a county office of education as a possible lending source. County offices of education are subject to K‑12 deferrals, so they may be experiencing their own challenges accessing cash.

Options to Consider

Since the state adopted the 2020‑21 budget in June 2020, it has received updated data on tax collections and program spending. In our recently released reports, The 2021‑22 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook and The 2021‑22 Budget: The Fiscal Outlook for Schools and Community Colleges, we show that the budget situation has improved considerably compared with June 2020 estimates. Continued uncertainty about the course of the pandemic and underlying economy, however, clouds our forecast. As the Legislature thinks about its budget priorities within this revised fiscal outlook, it likely will want to assess the possible implications for Proposition 98 payment deferrals. Below, we identify issues for the Legislature to consider regarding these deferrals.

Unprecedented Rebound in the Outlook for Proposition 98 Funding. Our recent budget reports show that state revenues are on track to be much higher than the June 2020 estimates. The much higher revenue projections contribute to much higher estimates of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. Prior to 2020‑21, the largest upward revision to the minimum guarantee (relative to the enacted budget) was $6.3 billion (10.3 percent) in 2014‑15. Compared with the estimates of the minimum guarantee in the June 2020 budget plan, we estimate the 2020‑21 guarantee is up $13.1 billion (18.5 percent). We project that the Proposition 98 increase is sustained in 2021‑22, with the guarantee that year a little higher than the 2020‑21 guarantee. When combined with changes in the 2019‑20 guarantee and certain other adjustments, we estimate that the state has about $13.7 billion that it needs to provide to settle up to the higher estimates of the guarantee. The Legislature could use these settle‑up funds for any one‑time school or community college purpose. Although we are relatively confident that 2020‑21 revenues will exceed June estimates, actual revenues could come in below our November estimates. In this case, the 2020‑21 minimum guarantee—and the resulting amount of one‑time Proposition 98 funds to spend—also would be several billion dollars lower than our November estimate.

Legislature Could Eliminate Existing Deferrals. Regardless of the exact amount of one‑time Proposition 98 funds available, the Legislature will face a key decision about how to allocate these funds. Any amount of $12.5 billion or more would be sufficient to eliminate all the K‑14 Proposition 98 payment deferrals. (Eliminating deferrals requires a one‑time Proposition 98 payment, as well as a Proposition 98 minimum guarantee that is high enough to accommodate the ongoing program spending moving forward.) We recommend the Legislature place a high priority on eliminating K‑14 deferrals. Eliminating all or part of these deferrals has several advantages. Notable advantages are reducing districts’ need for internal and external borrowing, reestablishing the link between ongoing program costs and ongoing funding, and giving the Legislature more budget tools to respond to future economic downturns. (Other options for using one‑time Proposition 98 settle‑up funds include addressing student learning loss and reducing districts’ unfunded pension liabilities.)

Two Main Options Regarding Timing. Should the Legislature decide to prioritize available one‑time funds for deferral paydowns, its next decision involves timing. The Legislature could (1) rescind the deferrals (either partially or fully) through immediate midyear action or (2) retain the scheduled current‑year deferrals but eliminate them going forward as part of the 2021‑22 budget. Below, we discuss these two options.

If Legislature Desires Midyear Action on Deferrals, Recommend Using Cautious Approach. Our estimate of state revenues—and the resulting Proposition 98 guarantee and availability of one‑time Proposition 98 funds in 2020‑21—is subject to notable uncertainty. If the Legislature decides to take early action (option 1), we thus would suggest a cautious approach. In January 2021, the Legislature could call off some, but not all, of the scheduled monthly deferrals. For example, it could rescind the February through April 2021 deferrals (which total about $7.2 billion between K‑12 and CCC) but leave intact the deferrals scheduled for May and June 2021. Even under our lower‑end estimates of the guarantee for 2020‑21, we estimate the state could accommodate the additional Proposition 98 spending associated with undoing the February through April deferrals. Depending on spring tax collections, the state then could decide in April whether to retain or rescind the May and June deferrals. Under this two‑step approach, some districts might still need TRANs (if their internal borrowing options are insufficient to cover the smaller remaining May and June deferral load), but the amount of external borrowing statewide would be much less than otherwise.

Legislature Would Need to Act Soon Should It Choose Midyear Option. The Legislature would need to take budget action in January 2021 since the first payment deferral is set to begin in February 2021. Some advance action is required because districts need to finalize the amount of TRAN proceeds they require before the notes are sold to investors in February. Once TRANs are sold, any subsequent decision by the Legislature to rescind or reduce the remaining deferrals will not eliminate the borrowing costs for the districts. Once issued, TRANs have a fixed maturity date and cannot be paid off early.

Option 1 Would Benefit Many, but Not All, Districts. Specifically, this option would benefit the approximately two‑thirds of CCC districts (plus many school districts) that are planning to use their reserves or borrow internally in response to the deferrals. By rescinding some of the deferrals and receiving associated on‑time payments from the state, these districts would not need to draw down their reserves or borrow internally to cover their monthly operating costs. They therefore would remain in better fiscal health and earn more interest on their reserves than had the deferrals been kept in place. Perhaps surprisingly, rescinding the current‑year deferrals would not necessarily benefit those districts that otherwise would have obtained a TRAN. Though not the intended objective of TRANs, many, if not all, districts pursuing TRANs might benefit from the transaction, as they would receive TRANs proceeds upfront and their short‑term investment earnings could exceed their borrowing costs.

Options 2 Also Has Benefits and Drawbacks. Option 2—paying off deferrals as part of the 2021‑22 budget package—reflects an even more cautious approach than option 1, with the state keeping all the deferrals in place through June 2021. The trade‑offs entailed in option 2 are basically the reverse of those entailed in option 1. That is, option 2 benefits those districts pursuing TRANs while not benefiting those districts relying on their reserves and internal borrowing. Under option 2, the districts receiving TRANs could benefit from additional investment earnings whereas districts needing to draw down their reserves would earn less than otherwise.

Under Either Option, Legislature Could Accelerate Repayment. If the state were to leave some deferrals in place in 2020‑21, it might be able to accelerate the schedule for repayment. For example, rather than repaying the May deferral in August, as originally scheduled, the state could repay in July. Even if the Legislature pursued option 2 and left all the deferrals in place in 2020‑21, it still might be able to repay all deferrals in July 2021 rather than stretching repayments from July 2021 through November 2021, as currently scheduled in statute. The Legislature could make these repayment decisions as part of budget close‑out in spring 2021. At that time, it would have updated data on its tax collections and available cash.