Updated 2/17/16: Figure 5 updated with new data from the administration.

February 9, 2021

The 2021-22 Budget

CalAIM: The Overarching Issues

The California Advancing and Innovating Medi‑Cal (CalAIM) proposal is a far‑reaching set of reforms to expand, transform, and streamline Medi‑Cal service delivery and financing. This post—the first in a series assessing different aspects of the Governor’s proposal—provides a brief overview of CalAIM, summarizes key changes from last year’s withdrawn proposal, analyzes overarching issues related to CalAIM, and ends by providing several key takeaways. Subsequent posts in this CalAIM series will evaluate issues related to financing, aging, and equity.

Background

Medi‑Cal Provides a Range of Health Care Services to a Variety of Populations. Medi‑Cal, the state’s Medicaid program, provides health coverage to about 13 million of the state’s low‑income residents. The program offers a comprehensive set of health care benefits and services, including primary care, inpatient services, prescription drugs, dental services, behavioral health services, maternity and newborn care, and long‑term care (both in institutions, such as skilled nursing facilities, and in the community, such as personal care services). Key Medi‑Cal populations include families and children, seniors and persons with disabilities (SPDs), and childless adults who are part of the eligibility expansion under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Many SPDs who are eligible for Medi‑Cal are simultaneously beneficiaries of Medicare. These individuals are called dual eligibles.

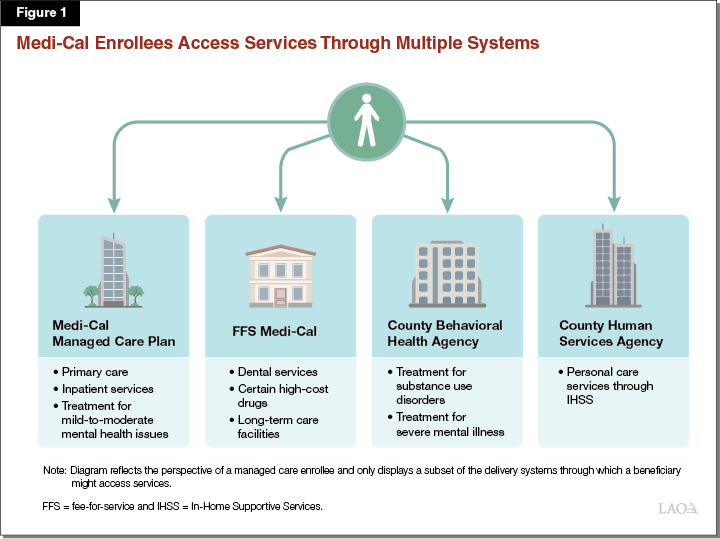

Medi‑Cal Is Complex. Services in the program are delivered through a variety of systems. The largest of these delivery systems is managed care, which serves more than 80 percent of enrollees. Managed care plans are responsible for arranging and paying for most health care services like primary care and hospital inpatient services utilized by their members. Medi‑Cal beneficiaries not enrolled in managed care receive such services through the fee‑for‑service (FFS) delivery system. Additionally, counties serve as distinct delivery systems both for treatment to Medi‑Cal enrollees with severe mental health conditions and for personal care services—the latter provided through the In‑Home Supportive Services program to Medi‑Cal beneficiaries who need assistance with daily living. Figure 1 illustrates the fragmentation and complexity of Medi‑Cal’s various delivery systems.

Governor Proposed CalAIM as Part of the January 2020‑21 Budget Before Withdrawing the Proposal in May. CalAIM is a large package of reforms aimed at (1) reducing health disparities by focusing attention and resources on Medi‑Cal’s high‑risk, high‑need populations; (2) rethinking behavioral health service delivery and financing, (3) transforming and streamlining managed care, and (4) extending federal funding opportunities currently available under the state’s soon‑to‑expire 1115 waiver. Originally proposed in January 2020 as part of the 2020‑21 budget, CalAIM was withdrawn at the May Revision due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) pandemic and the estimated effects it would have on the state’s fiscal situation. To maintain continuity of certain Medi‑Cal programs such as Whole Person Care and the Dental Transformation Initiative—whose federal authorization under the state’s 1115 waiver would have expired at the end of 2020—the state secured a one‑year extension of the 1115 waiver. With this extension, the state’s 1115 waiver is set to expire on December 31, 2021. For background on CalAIM, and analysis of the Governor’s prior‑year proposal, see our report, The 2020‑21 Budget: Re‑Envisioning Medi‑Cal—The CalAIM Proposal.

Governor’s Proposal

Overview

Reintroduces CalAIM in Largely Similar Form to Last Year’s Proposal. The Governor’s 2021‑22 budget reintroduces CalAIM. Figure 2 summarizes the major policy reforms included in the Governor’s CalAIM proposal, the vast majority of which are essentially unchanged from last year’s proposal except as relates to their proposed implementation time line.

Figure 2

Major Policy Reforms Under CalAIM Proposal

|

Increasing the Focus on High‑Risk, High‑Cost Populations |

|

Create new enhanced care management benefit. |

|

Ensure enrollment assistance for individuals transitioning from incarceration. |

|

Reimburse managed care plans to provide nonmedical “in lieu of services.” |

|

Require managed care plans to develop population health management programs. |

|

Convene foster care workgroup. |

|

Transforming and Streamlining Managed Care |

|

Transition certain benefits and enrollee populations from fee‑for‑service to managed care and vice versa. |

|

Modify approach to coordinating care of beneficiaries eligible for both Medi‑Cal and Medicare. |

|

Set capitated rates on a regional rather than county basis. |

|

Require NCQA accreditation of Medi‑Cal managed care plans; deem as meeting most federal and state standards. |

|

Consider creation of a full‑integration pilot. |

|

Rethinking Behavioral Health Service Delivery and Financing |

|

Streamline behavioral health financing. |

|

Seek new federal funding opportunity for residential mental health services. |

|

Change medical necessity criteria for beneficiaries to access services. |

|

Implement “no wrong door” approach for children obtaining mental health services. |

|

Integrate county administration of specialty mental health and substance use disorder services. |

|

Extending Components of the Current 1115 Waiver |

|

Continue public hospital funding under other programs. |

|

Maintain expansion of substance use disorder services begun under DMC‑ODS. |

|

Extend certain components of the Dental Transformation Initiative and provide a new covered benefit, silver diamine floride. |

|

CalAIM = California Advancing and Innovating Medi‑Cal; NCQA = National Committee on Quality Assurance; and DMC‑ODS = Drug Medi‑Cal Organized Delivery System. |

Key Changes and Clarifications From Last Year’s Proposal. While the updated CalAIM proposal is, in essence, the same as last year’s proposal, the following bullets summarize key changes and clarifications:

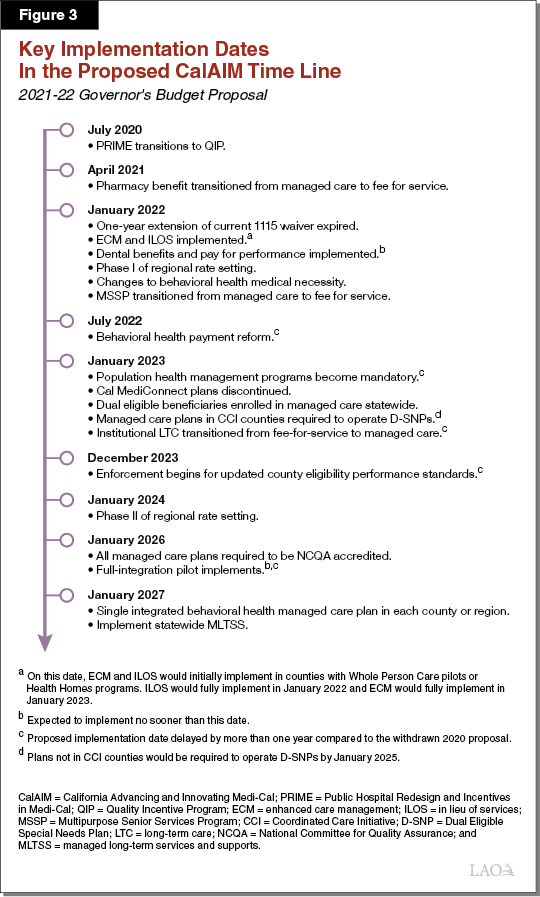

- Pushes Back and Makes Other Changes to the Implementation Time Line. The Governor’s proposed CalAIM implementation time lines generally have been delayed, in most cases by one year, to reflect last year’s withdrawal of the proposal and the one year extension the state received for its 1115 waiver (the state’s 1115 waiver authorizes many of the programs CalAIM seeks to maintain, often in modified form). In select cases, the Governor’s updated CalAIM proposal would delay by more than one year the implementation of certain reforms, compared to last year’s withdrawn proposal. Most notably, the updated proposal delays the transition of institutional long‑term care services into managed care by two years—to January 2023—with a rationale of aligning the timing of this transition with that of other major CalAIM changes affecting dual eligibles. Figure 3 summarizes the key dates in the Governor’s updated proposed time line for CalAIM implementation.

- Commits to Pursuing a New Federal Funding Opportunity for Residential Services to Treat Individuals With Mental Illness. In the updated CalAIM proposal, the administration announced a commitment to pursuing a federal waiver opportunity—known as the SMI/SED demonstration opportunity—to potentially receive federal reimbursement for services provided to individuals with Severe Mental Illness (SMI) and/or Severe Emotional Disturbance (SED) that are normally not eligible for federal funding. Specifically, these are services that are provided during short‑term stays in psychiatric hospitals or residential mental health facilities with more than 16 beds. In last year’s proposal, the administration had not reached a decision on pursuing this opportunity.

- Adds a New In‑Lieu of Service Benefit: Asthma Remediation Services. Under federal rules, “in lieu of services” (ILOS) generally are nonmedical services that can be provided as alternatives to standard Medicaid benefits in the managed care delivery system. ILOS are intended to be provided in place of a more expensive standard Medicaid benefit. As part of last year’s CalAIM package, the administration proposed a menu of ILOS that managed care plans could choose to provide. The updated CalAIM proposal includes a new benefit—asthma remediation services—to last year’s package of ILOS benefit proposals, bringing the total number of distinct ILOS that managed care plans may provide and receive reimbursement for to 14. These services would consist of physical modifications made to a beneficiary’s home to mitigate environmental triggers that exacerbate asthma conditions. The asthma remediation benefit generally would be limited to a maximum amount of $5000 in a beneficiary’s lifetime. Figure 4 lists and summarizes the proposed ILOS benefits.

Figure 4

Proposed “In Lieu of Services” Benefits

|

Benefit |

Description |

|

Services to Address Homelessness and Housing |

|

|

Housing depositsa |

Funding for one‑time services necessary to establish a household, including security deposits to obtain a lease, first month’s coverage of utilities, or first and last month’s rent required prior to occupancy. |

|

Housing transition navigation servicesa |

Assistance with obtaining housing. This may include assistance with searching for housing or completing housing applications, as well as developing an individual housing support plan. |

|

Housing tenancy and sustaining servicesa |

Assistance with maintaining stable tenancy once housing is secured. This may include interventions for behaviors that may jeopardize housing, such as late rental payment and services, to develop financial literacy. |

|

Services for Long‑Term Well‑Being in Home‑Like Settings |

|

|

Asthma remediationb |

Physical modifications to a beneficiary’s home to mitigate environmental asthma triggers. |

|

Day habilitation programs |

Programs provided to assist beneficiaries with developing skills necessary to reside in home‑like settings, often provided by peer mentor‑type caregivers. These programs can include training on use of public transportation or preparing meals. |

|

Environmental accessibility adaptations |

Physical adaptations to a home to ensure the health and safety of the beneficiary. These may include ramps and grab bars. |

|

Meals/medically tailored meals |

Meals delivered to the home that are tailored to meet beneficiaries’ unique dietary needs, including following discharge from a hospital. |

|

Nursing facility transition/diversion to assisted living facilitiesc |

Services provided to assist beneficiaries transitioning from nursing facility care to community settings, or prevent beneficiaries from being admitted to nursing facilities. |

|

Nursing facility transition to a home |

Services provided to assist beneficiaries transitioning from nursing facility care to home settings in which they are responsible for living expenses. |

|

Personal care and homemaker servicesd |

Services provided to assist beneficiaries with daily living activities, such as bathing, dressing, housecleaning, and grocery shopping. |

|

Recuperative Services |

|

|

Recuperative care (medical respite) |

Short‑term residential care for beneficiaries who no longer require hospitalization, but still need to recover from injury or illness. |

|

Respite |

Short‑term relief provided to caregivers of beneficiaries who require intermittent temporary supervision. |

|

Short‑term post‑hospitalization housinga |

Setting in which beneficiaries can continue receiving care for medical, psychiatric, or substance use disorder needs immediately after exiting a hospital. |

|

Sobering centers |

Alternative destinations for beneficiaries who are found to be intoxicated and would otherwise be transported to an emergency department or jail. |

|

aRestricted to use once in a lifetime, unless managed care plan can demonstrate cost‑effectiveness of providing a second time. bNew benefit introduced this year. Restricted to lifetime maximum amount of $5000, unless beneficiary’s condition changes dramatically. cIncludes residential facilities for the elderly and adult residential facilities. dDoes not include services already provided in the In‑Home Supportive Services program. |

|

Updated Funding Plan

Updated CalAIM Funding Plan Is Similar to Last Year’s, With Certain One‑Time Components Added. Various components of CalAIM are expected to result in new state costs, while others are anticipated to be cost neutral or to result in state or local savings. On net, CalAIM is expected to result in higher costs, at least in the short and medium term. As shown in Figure 5, in 2021‑22, the Governor proposes spending $532 million General Fund ($1.1 billion total funds) on the first half‑year of CalAIM implementation (by and large, CalAIM implementation would begin on January 1, 2022). CalAIM would increase to $756 million General Fund ($1.5 billion total funds) in 2022‑23 and 2023‑24, lowering to $424 million General Fund ($846 million total funds) beginning in 2024‑25 and ongoing. The increase from 2021‑22 to 2022‑23 reflects the shift from half‑year to full‑year funding, while the decrease starting in 2024‑25 is due to the expiration of certain limited‑term funding components, most notably the managed care plan incentive payments.

Figure 5

Proposed CalAIM Funding—Governor’s 2021‑22 Budget

(In Millions)

|

2021‑22 |

2023‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 and Ongoing |

||||||||

|

Total Funds |

General Fund |

Total Funds |

General Fund |

Total Funds |

General Fund |

Total Funds |

General Fund |

||||

|

Plan incentivesa |

$300 |

$150 |

$600 |

$300 |

$600 |

$300 |

— |

— |

|||

|

Enhanced care management |

188 |

94 |

467 |

233 |

490 |

245 |

$490 |

$245 |

|||

|

In lieu of services |

48 |

24 |

115 |

58 |

115 |

58 |

115 |

58 |

|||

|

Dental services |

113 |

57 |

227 |

114 |

227 |

114 |

227 |

114 |

|||

|

Behavioral health QIP |

22 |

22 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

— |

— |

|||

|

Benefit and population delivery system transitionsb |

403 |

175 |

‑10 |

‑5 |

‑10 |

‑5 |

‑10 |

‑5 |

|||

|

Local Assistance Subtotal |

($1,074) |

($521) |

($1,431) |

($732) |

($1,454) |

($744) |

($822) |

($415) |

|||

|

DHCS state operations |

$24 |

$11 |

$28 |

$13 |

$25 |

$12 |

$24c |

$11c |

|||

|

Grand Totals |

$1,098 |

$532 |

$1,459 |

$745 |

$1,479 |

$756 |

$846 |

$423 |

|||

|

aTo assist with the establishment of enhanced care management and in lieu of services. bNot included in last year’s proposal. cWhile the 2024‑25 costs are as listed, ongoing costs are proposed to be $20 million total funds, $10 million General Fund. |

|||||||||||

|

Note: Totals may not add due to rounding. |

|||||||||||

|

QIP = Quality Incentive Payments and DHCS = Department of Health Care Services. |

|||||||||||

The updated funding plan for CalAIM is substantially similar to last year’s funding plan. As with last year’s proposal, the Governor’s budget provides upfront funding for enhanced care management (ECM), ILOS, and infrastructure managed care plans need to be able to deliver those benefits. Additionally, consistent with last year’s proposal, the budget funds a dental pay‑for‑performance program and a new dental benefit, silver diamine fluoride.

Not part of last year’s budget proposal, the updated 2021‑22 funding plan includes one‑time costs related to the transition of certain benefits and populations into and out of managed care. (CalAIM proposes various benefit and enrollee population transitions between managed care and FFS.) While last year’s proposal included these transitions, the proposal did not include the associated funding. These transitions create additional costs due to differences in service reimbursement timing between the managed care and FFS delivery systems.

Statutory Changes to Implement CalAIM Are Needed. We understand that significant state statutory changes are needed to implement CalAIM. The administration released the statutory changes in the form of proposed trailer bill language in early February. The administration also has expressed openness to pursuing at least some CalAIM statutory changes through the policymaking process should that be the Legislature’s preference.

Assessment

As we describe below, significant detail on the CalAIM proposal remains outstanding. In part, this is because many policy details remain under development. As further details emerge, we will update the Legislature on any changes to our assessment of the Governor’s proposal.

Since the updated CalAIM proposal is essentially the same as last year’s withdrawn proposal—and many of the same details remain outstanding—many of the questions and issues for consideration that we raised in last year’s CalAIM report remain relevant. Nevertheless, in the assessment that follows, we re‑emphasize key considerations and incorporate updated commentary on the Governor’s proposal to undertake a major set of health care delivery and financing reforms concurrently with COVID‑19 response and recovery activities.

CalAIM Could Bring Major Benefits…

Potentially Could Reduce Health Disparities and Improve Service Delivery. Health disparities exist when one population group experiences systematically worse health outcomes than another population group. Population groups can be categorized in different ways, such as by demographic characteristics like race and gender, by geography, by socioeconomic status, or by the other factors like health conditions or access to housing. For example, individuals experiencing homelessness are disproportionately likely to develop health conditions such as mental illness, which is associated with comorbidities and excess mortality. CalAIM is intended to improve and expand service delivery, in particular for Medi‑Cal’s highest‑risk, highest‑need beneficiaries who often suffer worse health outcomes. The target populations for these efforts include, for example, homeless individuals, high utilizers, SPDs at risk of institutionalization in nursing homes or hospitals, and individuals transitioning from incarceration. By better targeting and delivering services to Medi‑Cal’s highest‑risk, highest‑need beneficiaries, CalAIM potentially could reduce health disparities by improving the health of those who regularly suffer from worse health outcomes. The following bullets summarize several of the ways CalAIM could improve service delivery and, in doing so, reduce health disparities.

- Potentially Expanding the Availability of Supportive Services. Gaps in the coordination and availability of supportive services likely impede access to such services, impair health and social outcomes, and result in costs throughout the safety net that might be averted through better and more timely support. For example, providing housing navigation services to individuals who currently lack stable housing may help them avoid developing serious conditions associated with chronic homelessness. By allowing managed care plans to provide ILOS, and have these costs reflected in their capitated rates, CalAIM could encourage them to provide these types of services.

- Improving Care Coordination. As previously alluded to, CalAIM proposes to create a new statewide managed care benefit, ECM, to provide intensive case management and care coordination for Medi‑Cal’s most high‑risk and high‑need beneficiaries (provided they are enrolled in managed care). The intent is for ECM to provide much more high‑touch, community‑centered care coordination services than are generally available to the targeted populations, which include, for example, high utilizers of emergency departments and members with unstable housing. The objective is for ECM to play an important role in connecting high‑risk, high‑need members to the appropriate ILOS and other, more standard preventive services necessary for the improvement of health outcomes. Additionally, the CalAIM proposal includes provisions meant to build on the work of the Coordinated Care Initiative to improve Medi‑Cal and Medicare coordination for dual eligibles. (A future post will explore this coordination in greater depth.) The CalAIM proposal also takes steps to improve coordination of behavioral care by integrating specialty mental health services and substance use disorder services under a single behavioral health managed care plans in the majority of the state’s counties.

- Reducing Delivery System Complexity. Several aspects of the CalAIM proposal could address some of the complexity in the current Medi‑Cal program and move toward greater standardization (both across program components and across the state) and simplicity. Key examples of the increased standardization and simplification include: (1) standardizing which benefits are covered through managed care statewide, such as by carving in institutional long‑term care; (2) requiring plans statewide to provide coordinated managed care to dual eligibles; and (3) expanding the potential to have a more comprehensive approach to addressing the needs of high‑cost populations, such as those provided through the Whole Person Care and Health Homes programs, through ECM and ILOS benefits statewide.

- Modernizing Behavioral Health Service Delivery and Financing. The proposed behavioral health reforms under the CalAIM proposal could improve behavioral health service delivery in a number of ways. Revised medical necessity criteria (that focus more on level of impairment) could lead to beneficiaries accessing needed services earlier. The proposed financing reforms also could give county mental health plans more flexibility to pursue payment models that incentivize the quality of care provided and reduce the administrative burden associated with tying reimbursement to cost. CalAIM also presents an opportunity for the state to draw down additional federal funding through Medi‑Cal for (1) services provided in settings previously ineligible for federal reimbursement through the SMI/SED demonstration opportunity, and (2) services provided to beneficiaries without a covered diagnosis. This additional federal funding could increase capacity to provide services, to the extent that it frees up county funding to make further investments in the behavioral health system.

CalAIM Could Strengthen Managed Care Plans’ Capacities and Incentives to Coordinate Care. The administration’s CalAIM proposal reflects a vision that managed care is uniquely positioned to effectively and efficiently manage not only the basic health care needs of Medi‑Cal beneficiaries, but also many of their broader social support needs as well. Through ECM and ILOS, CalAIM would authorize and fund managed care plans to provide higher levels of care coordination and an expanded array of nonmedical benefits. Through these new benefits, for example, CalAIM vests managed care plans with tools to better identify and address their members’ housing needs by paying apartment rental deposits, nutritional needs by providing medically tailored meals, and home‑environmental needs by installing ramps or employing asthma remediation services. Today, such services generally are accessible through other systems of care, but in many cases outside of Medi‑Cal.

Moreover, under CalAIM, additional Medi‑Cal services would become accessible primarily through managed care. For example, institutional long‑term care (LTC), such as nursing facility stays, would become a statewide managed care benefit. (Currently, institutional LTC is only carved into managed care in certain counties.) In giving plans new tools (ECM and ILOS) and consolidating financial responsibility for institutional care within managed care (plans are already responsible for covering hospital inpatient services), CalAIM has the potential to strengthen plan incentives to deliver preventive and supportive services that could divert costly institutional care where possible. (Whether plans will be successful is an outstanding question that we discuss below.)

…But Major Overarching Questions Still Remain

Is Managed Care Well Positioned for a Significant Expansion of Responsibilities? Recent evaluations of Medi‑Cal managed care have raised questions about the extent to which managed care plans are meeting their core responsibilities of ensuring access to high‑quality, appropriate care, particularly in the area of prevention. For example, the California State Auditor recently found that utilization of children’s preventive services in Medi‑Cal—which managed care plans are primarily responsible for arranging—lags that of most other state Medicaid programs. CalAIM would layer new responsibilities onto managed care plans, requiring or encouraging them to (1) significantly improve their capacities to identify and target specialized services to their high‑risk, high need members; (2) arrange and pay for services for which they have limited experience offering (such as housing services and long‑term services and supports); (3) and provide integrated care for Medi‑Cal members also enrolled in Medicare. How managed care plans will balance their new responsibilities under CalAIM while meeting their core responsibilities—particularly as implementation occurs as the country deals with a pandemic—is a major outstanding question.

Whether managed care plans are positioned to take on these new responsibilities is not simply a question of readiness in the near term. The initial years of CalAIM are intended to test new approaches and expand plan capacities. The longer‑term vision is broader and includes, for example, the piloting of fully integrated managed care where managed care plans would be fully responsible for providing physical health care, dental services, behavioral health, and long‑term services and supports (the latter three of which are, to varying extents, not accessed currently through managed care). Ultimately, this vision would concentrate responsibilities for meeting the medical and nonmedical needs of Medi‑Cal members within managed care. While such concentration has the potential to reduce fragmentation, improve care coordination, and align fiscal incentives, the nature, management, and financing of Medi‑Cal services could look significantly different than today under the long‑term vision for CalAIM. In its deliberations of CalAIM, the Legislature may wish to consider whether managed care is best positioned to take on the expanded role envisioned by the Governor’s proposal.

Would New Benefits Expand the Supply of Already Limited Services? The success of the CalAIM proposal would depend, in part, on Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ ability to marshal community resources to serve the broader, nonmedical needs of their members. As such, limits in the availability of community resources could impair the effectiveness of the reform effort, as well as the speed of its success. For example, constraints in the local housing supply in certain communities could make assisting members in obtaining appropriate housing a challenge for managed care plans.

What New Complexities Does CalAIM Create? While CalAIM would streamline and simplify Medi‑Cal in some ways, it also would result in new complexities. For example, the ILOS benefits available to a beneficiary would vary depending on where they live in the state and what managed care plan they are enrolled in. Additionally, the CalAIM proposal represents a significant increase in the role of managed care plans to provide nonmedical supportive services to individuals with complex needs, including individuals experiencing homelessness. There are multiple other entities that administer homelessness services and other programs targeted at these populations. Expanding the role of managed care plans to provide these nonmedical supports could further fragment the delivery, financing, and administration of these services.

Does a Major Ongoing Augmentation Make Sense in Light of the State’s Projected Multiyear Shortfall? Under the Governor’s budget proposal, the state would spend hundreds of millions of dollars of General Fund monies on an ongoing basis to implement CalAIM. Unlike when CalAIM was proposed in January 2020, the 2021‑22 proposal comes in the context of a projected multiyear budget deficit. While much of CalAIM represents novel changes to how Medi‑Cal services are delivered and financed, most of the proposed new General Fund spending reflects a change in how the state would fund fairly new but existing services. For example, programs such as Whole Person Care and the Dental Transformation Initiative, currently authorized under the 1115 waiver and funded with a mix of federal and non‑General Fund state and local funds, expire at the end of 2021. Under CalAIM, ECM, ILOS, and dental pay for performance would build upon and replace expiring programs, such as those mentioned above, but use General Fund to cover the nonfederal share of costs rather than the existing fund sources. We will further explore how and why the Governor’s proposal reflects a change in funding responsibility in our forthcoming post on CalAIM financing issues.

Is the Funding Plan Reasonable and What Are the Longer‑Term Fiscal Risks? Following our preliminary review, the Governor’s 2021‑22 spending proposal for CalAIM largely appears reasonable. However, we have some outstanding questions about the reasonableness of the Governor’s CalAIM funding plan, both in 2021‑22 and in later years. For example, CalAIM involves a broad array of new requirements on county partners (who play a key role in administering and delivering various services available through Medi‑Cal). Specifically, CalAIM would make various changes that affect county responsibilities, such as (1) the transfer of responsibility for covering specialty mental health services in two counties where today a Medi‑Cal managed care plan (Kaiser) covers such services and (2) new requirements for counties to initiate the Medi‑Cal enrollment process and coordinate care for county inmates. The funding plan does not appear to reimburse counties for these costs despite potential responsibility on the part of the state to reimburse counties for new state mandates placed on them.

In addition, ongoing spending on CalAIM partially would depend on the reform’s success in diverting costly services such as emergency room visits and LTC facility stays through better coordination and access to preventive and social supportive services. The degree to which these preventive and social supportive services would replace or supplement more costly services is uncertain. As we summarized in last year’s report on CalAIM, research on this question is mixed. If the new services prove to supplement rather than replace more costly Medi‑Cal services, the ongoing costs of CalAIM could be significantly more costly than the Governor’s funding plan projects. We will explore further the reasonableness of the funding plan and potential longer‑term fiscal risks in a companion post analyzing CalAIM financing issues.

Is the Updated Implementation Time Line Realistic? Implementing the numerous CalAIM reforms would be complex and create significant new workload for the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), managed care plans, counties, and service providers. The proposed time line for CalAIM is ambitious. Compared to last year’s withdrawn proposal, most implementation deadlines have been delayed by just one year. As a result, many policy changes would be implemented in less than one year from the release of the Governor’s updated proposal—beginning on January 1, 2022. These include ECM, ILOS, various managed care standardization efforts, changes to medical necessity in behavioral health, and others. Additional major changes are scheduled to phase in over each of the next five years. At the same time as CalAIM is scheduled to be implemented, capacity among the key administrators and service providers is likely to continue to be strained by COVID‑19 pandemic response and recovery activities. Delays in CalAIM implementation appear inevitable.

How Would the Reforms Be Overseen and Evaluated? Given the scope of CalAIM’s reforms, robust evaluation is critical for ensuring the service expansions and delivery system transformations are producing their intended benefits. Standard mechanisms for legislative oversight, such as the budget hearing process, may not be sufficient for ensuring enhanced oversight of initial implementation of CalAIM. Moreover, to date, the administration has not released a plan for how CalAIM will be evaluated. While DHCS has committed to careful performance monitoring, oversight, and evaluation of CalAIM and its implementation, the Legislature’s role in ensuring effective and smooth implementation has yet to be fully worked out and established.

Key Takeaways

Use Budget and Policy Processes to Resolve Key Outstanding Questions and Provide Legislative Input. The CalAIM proposal is ambitious and far‑reaching. Summaries of the CalAIM package, even when extensive, cannot fully highlight all the policy decisions embedded in the proposal. Furthermore, the administration has not yet provided all the information required to perform a detailed evaluation of the proposal (in some cases, this likely is because policy decisions have yet be finalized). Because of this, we are unable to provide specific direction on the actions we would recommend the Legislature take on the proposal. Instead, we suggest that the Legislature focus primarily on resolving key questions about the proposal prior to taking action on it. Figure 6 summarizes the key outstanding questions that we have about the Governor’s proposal.

Figure 6

CalAIM Questions for Legislative Focus

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CalAIM = California Advancing and Innovating Medi‑Cal. |

Explore Where Delays in Implementation May Be Possible and Advisable. The scope and speed of CalAIM implementation under the Governor’s plan create two significant challenges. First, many important policy decisions on which CalAIM components to adopt would have to be made by the summer of 2021. This affords the Legislature little time to closely scrutinize and decide upon each of CalAIM’s numerous reform components, which would have to occur while the Legislature continues to work on and through the COVID‑19 pandemic. Second, the ambitiousness of the implementation time line could place strains on state and local program administrators and other implementation partners. This may increase the likelihood of delays and has the potential to disrupt care for beneficiaries.

Some of CalAIM’s proposed implementation dates appear difficult to move as their implementation dates coincide with the expiration of federal authority for the programs they are intended to replace. (Whether the state could request further extensions of the existing federal authorities is unclear.) Other CalAIM implementation dates appear to more closely coincide with state‑imposed deadlines, such as requirements for plans to have operational population health management programs. To afford itself more time to scrutinize the many reforms under CalAIM and grant the state’s currently stressed health care infrastructure more time to implement CalAIM’s major changes, the Legislature could explore (1) which decisions can be deferred and (2) which implementation dates can be delayed.

Consider Putting a Process in Place to Ensure Legislative Oversight of Implementation. Given the scope, complexity, and speed of the CalAIM proposal, legislative oversight of CalAIM components that ultimately are adopted would be critical for ensuring smooth and successful implementation. Accordingly, prior to January 2022, the Legislature could consider requiring regular check‑ins with the administration, managed care plans, and other implementation partners to discuss readiness for implementation. After January 2022, the Legislature could expand the focus of these check‑ins to include monitoring of the successes and challenges of CalAIM implementation.

Require a Comprehensive and Independent Evaluation. CalAIM comprises a large number of individual reforms, many of them relatively untested, that altogether represent a significant departure from how Medi‑Cal benefits are delivered today. To understand the impacts of CalAIM, we recommend that the Legislature establish a framework for a robust, independent, and public evaluation of whichever major components of the CalAIM proposal ultimately are adopted. As ascertaining the true and myriad impacts of a reform effort this large will be a significant challenge, we recommend that the Legislature consider providing direction over who performs and oversees the evaluation and what pre‑identified measures of success should receive focus. Any such evaluation(s) should be available, at least in preliminary form, prior to any deadlines for deciding on whether to reauthorize any major components of CalAIM.