LAO Contact

February 11, 2021

The 2021-22 Budget

Analysis of Child Welfare Proposals

California’s children and family programs include an array of services to protect children from abuse and neglect and to keep families safely together when possible. This analysis: (1) provides program background; (2) outlines the Governor’s proposed budget for children and family programs, including child welfare services (CWS) and foster care programs, in 2021‑22; and (3) provides key questions and issues for the Legislature to consider as it evaluates the budget proposal.

Program Background

CWS. When children experience abuse or neglect, the state provides a variety of services to protect children and strengthen families. The state provides prevention services—such as substance use disorder treatment and in‑home parenting support—to families at risk of child removal, to help families remain together if possible. When children cannot remain safely in their homes, the state provides temporary out‑of‑home placements through the foster care system, often while providing services to parents with the aim of safely reunifying children with their families. If children are unable to return to their parents, the state provides assistance to establish a permanent placement for children, for example, through adoption or guardianship. California’s counties carry out children and family program activities for the state, with funding from the federal and state governments, along with local funds.

2011 Realignment. Until 2011‑12, the state General Fund and counties shared significant portions of the nonfederal costs of administering CWS. In 2011, the state enacted legislation known as 2011 realignment, which dedicated a portion of the state’s sales and use tax and vehicle license fee revenues to counties to administer child welfare and foster care programs. As a result of Proposition 30 (2012), under 2011 realignment, counties either are not responsible or only partially responsible for CWS programmatic cost increases resulting from federal, state, and judicial policy changes. Proposition 30 establishes that counties only need to implement new state policies that increase overall program costs to the extent that the state provides the funding. Counties are responsible, however, for all other increases in CWS costs—for example, those associated with rising caseloads. Conversely, if overall CWS costs fall, counties retain those savings.

Continuum of Care Reform (CCR). Beginning in 2012, the Legislature passed a series of legislation implementing CCR. This legislative package makes fundamental changes to the way the state cares for youth in the foster care system. Namely, CCR aims to: (1) end long‑term congregate care placements; (2) increase reliance on home‑based family placements; (3) improve access to supportive services regardless of the kind of foster care placement a child is in; and (4) utilize universal child and family assessments to improve placement, service, and payment rate decisions. Under 2011 realignment, the state pays for the net costs of CCR, which include upfront implementation costs. While not a primary goal, the Legislature enacted CCR with the expectation that reforms eventually would lead to overall savings to the foster care system, resulting in CCR ultimately becoming cost neutral to the state. We note that CCR is a multiyear effort—with implementation of the various components of the reform package beginning at different times over several years—and the state continues to work toward full implementation in the current year. For more detailed background on CCR and its various components, refer to our previous CCR budget update here.

Extended Foster Care (EFC). At around the same time as 2011 realignment, the state also implemented the California Fostering Connections to Success Act (Chapter 559 of 2010 [AB 12, Beall]), which extended foster care services and supports to youth from age 18 up to age 21, beginning in 2012. To be eligible, a youth must have a foster care order in effect on their 18th birthday, must opt in to receive EFC benefits, and must meet certain criteria (such as pursuing higher education or work training) while in EFC. Youth participating in EFC are known as non‑minor dependents (NMDs). In addition to case management services, NMDs receive support for independent or transitional housing.

Foster Placement Types. As described above, when children cannot remain safely in their homes, they may be removed and placed into foster care. Counties rely on various placement types for foster youth. Pursuant to CCR, a Child and Family Team (CFT) provides input to help determine the most appropriate placement for each youth, based on the youth’s socio‑emotional, behavioral and mental health needs, and other criteria. Placement types include:

- Placements With Resource Families. For most foster youth, the preferred placement type is in a home with a resource family. A resource family may be kin (either a non‑custodial parent or relative), a foster family approved by the county, or a foster family approved by a private foster family agency (FFA). FFA‑approved foster families receive additional supports through the FFA and therefore may care for youth with higher‑level physical, mental, or behavioral health needs.

- Congregate Care Placements. Foster youth with intensive behavioral or mental health needs preventing them from being placed safely or stably with a resource family may be placed in a Short‑Term Residential Therapeutic Program (STRTP). These facilities provide specialty mental and behavioral health services and 24‑hour supervision. STRTP placements are designed to be short term, with the goal of providing the needed care and services to safely transition youth to resource families.

- Independent and Transitional Placements for Older Youth. Older, relatively more self‑sufficient youth and NMDs may be placed in supervised independent living placements (SILPs) or transitional housing placements. SILPs are independent settings, such as apartments or shared residences, where NMDs may live independently and continue to receive monthly foster care payments. Transitional housing placements provide foster youth ages 16 to 21 supervised housing as well as supportive services, such as counseling and employment services, that are designed to help foster youth achieve independence.

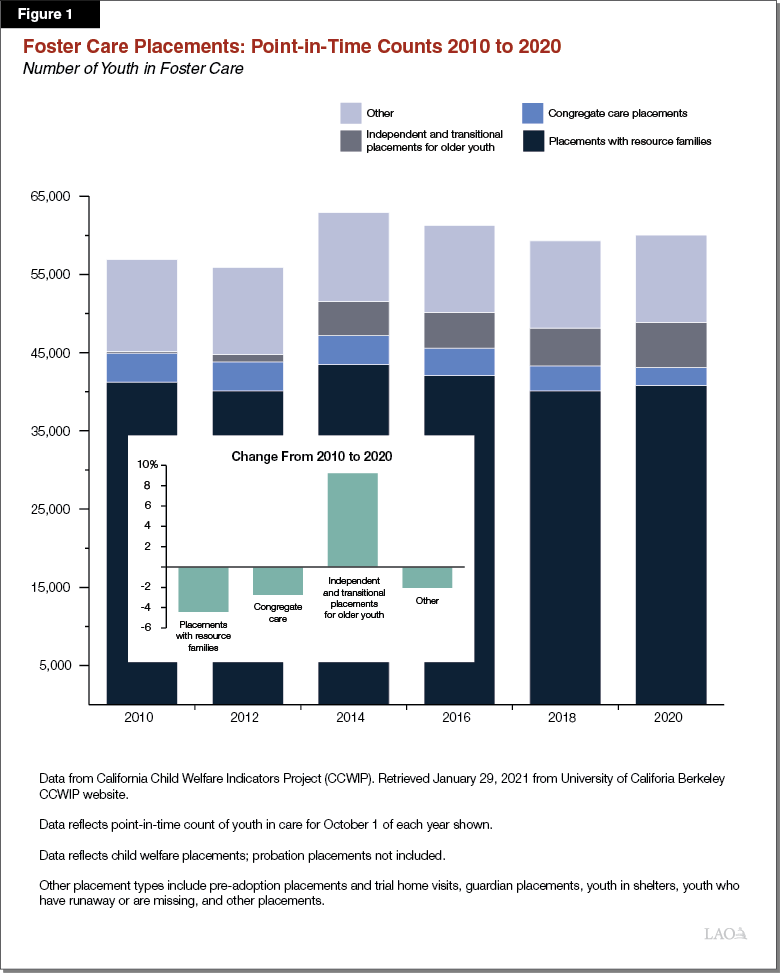

Total Foster Care Placements Have Remained Stable, With Shifts in Placement Types. Over the past decade, the number of youth in foster care has remained around 60,000 (ranging from around 55,000 to around 63,000 at any point in time). While the total number of placements has remained stable, the predominance of various placement types has shifted over time. In particular, pursuant to the goals of CCR, congregate care placements have decreased, while more independent placements have increased since the implementation of EFC. Figure 1 illustrates changes in foster placements over time.

Federal Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA). Historically, one of the main federal funding streams available for foster care—Title IV‑E—has not been available for states to use on services that may prevent foster care placement in the first place. Instead, the use of Title IV‑E funds has been restricted to support youth and families only after a youth has been placed in foster care. Passed as part of the 2018 Bipartisan Budget Act, FFPSA expands allowable uses of federal Title IV‑E funds to include services to help parents and families from entering (or re‑entering) the foster care system. Specifically, FFPSA allows states to claim Title IV‑E funds for mental health and substance abuse prevention and treatment services, in‑home parent skill‑based programs, and kinship navigator services once states meet certain conditions. FFPSA additionally makes other changes to policy and practice to ensure the appropriateness of all congregate care placements, reduce long‑term congregate care stays, and facilitate stable transitions to home‑based placements.

The law is divided into several parts; Part I (which is optional and related to prevention services) and Part IV (which is required and related to congregate care placements) have the most significant impacts for California. States are required to implement Part IV by October 1, 2021 in order to prevent the loss of federal funds for congregate care. States may not implement Part I until they come into compliance with Part IV.

Overview of Governor’s Budget

Total Funding for Child Welfare Services and Foster Care Increases, While State and Federal Shares Decrease Slightly. As illustrated by Figure 2, the 2021‑22 Governor’s Budget proposal estimates total spending for child welfare programs would increase by around $264 million from 2020‑21 to 2021‑22. This net change includes decreases in federal and state General Fund spending, offset by increases in county spending and Title XIX reimbursement for health‑related activities.

Figure 2

Proposed Local Assistance for Child Welfare and Foster Care

Includes Child Welfare Services, Foster Care, AAP, KinGAP, and CalWORKS ARC (In Millions)

|

Total Funds |

Federal Funds |

State |

County Funds |

Reimbursement |

|

|

2020‑21 revised budget |

$7,083 |

$3,260 |

$845 |

$2,799 |

$179 |

|

2021‑22 Governor’s Budget proposal |

7,347 |

3,251 |

797 |

3,110 |

189 |

|

Change |

$264 |

‑$9 |

‑$48 |

$311 |

$10 |

|

Notes: DSS made display adjustments to county funds to reflect more holistic expenditures, including growth to the LRF subaccounts. The display adjustments include partial changes in 2020‑21 and full‑year changes in 2021‑22. This resulted in what appears to be a year‑over change for county funds of more than $1.5 billion. For future years, DSS’ display will include LRF adjustments, and we will update our numbers accordingly. For this table, however, we have removed the display changes to ensure year‑over changes in county and total funds do not appear overly large. AAP = Adoption Assistance Program; KinGAP = Kinship Guardianship Assistance Payment; ARC = Approved Relative Caregiver; DSS= Department of Social Services; and LRF = Local Revenue Fund. |

|||||

Primary drivers of the federal and state funding decreases include:

- Expiration of Temporary Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) Increase. In response to the pandemic, the federal government is providing a temporary 6.2 percent increase to FMAP for eligible Title IV‑E foster care, adoptions assistance, and kinship guardian cases. The Governor’s budget assumes the temporary FMAP increase ends midyear 2021‑22, meaning increased funds are budgeted for all of 2020‑21 but only part of 2021‑22.

- Expiration of Federal Supplemental Title IV‑B Funds. Also in response to the pandemic, the federal government provided one‑time supplemental federal Title IV‑B funds through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act. This funding for eligible CWS may be expended through September 2021.

- Ramp Down of Federal Family First Transition Act Funding. The federal Family First Transition Act supports counties in their transition to FFPSA. For counties that previously participated in Title IV‑E Waiver Demonstration Projects (which ended in September 2019), funding certainty grants—based on funding provided to counties through the waiver projects in federal fiscal year 2019—are provided in federal fiscal years 2020 and 2021. Maximum grant amounts decrease from 90 percent of base year funding in 2020 to 75 percent of base year funding in 2021. In addition, the federal government provided one‑time grant funding in 2020 to help all counties begin to implement FFPSA.

- Ramp Down of Some State Pandemic Response Efforts. Some one‑time and limited‑term state expenditures for pandemic response are projected to end in 2020‑21, while others are projected to end midway through 2021‑22. We discuss pandemic response for child welfare programs in more detail later in this post.

- Decrease in State Funding for Placement Prior to Approval for Emergency Caregivers. When children are removed from their homes, certain individuals (primarily relatives) are eligible to begin providing foster care without prior approval as a resource family. Current statute dictates these eligible individuals may receive foster payments for up to 120 days (or up to 365 days if a good‑cause extension is warranted) while completing the resource family approval process. In 2021‑22, the statutory time limit for pre‑approval funding decreases to 90 days, without any option for extension.

- Expiration of One‑time State Funds for Counties in 2020‑21. The state provided a one‑time payment of $80 million to counties in 2020‑21 for CWS. We understand these funds were intended to reimburse counties for some CCR‑related implementation costs.

The state and federal funding reductions described above are partially offset by some notable increases in federal and state child welfare spending in 2021‑22:

- State and Federal Increases for Home‑Based Family Care (HBFC) Rates. Pursuant to CCR, foster care payments are shifting from the prior age‑based rate system to universal HBFC rates for resource families. Resource families caring for youth with a higher level of need—as assessed through a Level of Care (LOC) protocol tool—receive higher monthly foster care payment rates. In 2021‑22, HBFC rates receive a statutory cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA). Additionally, we understand that the administration’s estimate assumes the LOC protocol tool is fully rolled out in 2021‑22. To date, however, the tool has been rolled out only to FFA placements and there is no clear time line for roll out to county‑approved resource family placements at this time. We are working with the administration to better understand what portion of the HBFC rate increase is due to LOC assumptions. We provide more detail about the LOC protocol tool and its implementation in our previous child welfare budget analysis here.

- Slight Increase in Funding for Other CCR Expenditures. The Governor continues to propose the state provide funding for counties to implement some elements of CCR. Aside from funding for HBFC rates and placement prior to approval for emergency caregivers—both of which are described above—other CCR expenditures include: CFTs, Resource Family Approval (RFA), LOC protocol tool, Statewide Automated Welfare System project, second level administration review, contracts, and CCR reconciliation. We provide more detail about these elements of CCR in our previous child welfare budget analysis here. Funding for most of these CCR elements is unchanged year over year, while funding for CFTs increases by a few million dollars in 2021‑22, reflecting more up‑to‑date caseload estimates.

- FFPSA Part IV Implementation. The administration’s 2021‑22 budget proposal includes funding for several new activities related to implementing Part IV of FFPSA. We describe the administration’s FFPSA proposal in more detail later in this post.

- Other Changes, Including Federal Increases for Realigned Programs. Other changes in estimated expenditures from 2020‑21 to 2021‑22 reflect expected annual growth of realigned programs, such as for foster care assistance payments ($30 million federal increase), adoption assistance program payments ($16 million federal increase), county administration of foster care ($31 million federal increase), and CWS program costs ($118 million federal increase). These changes reflect updated expenditure data, COLAs, and projected caseload growth.

Figure 3 summarizes all of the federal and state funding changes described above.

- County Expenditures Increase Primarily Due to Growth in Realigned Programs. The estimated increase in county expenditures from 2020‑21 to 2021‑22 reflects the administration’s projections based on historical expenditure trends for realigned programs, including foster care assistance payments and administration, adoption assistance program payments and administration, and CWS program costs. Additionally, the estimated increase in county expenditures includes the administration’s assumptions about the county share of costs to implement FFPSA Part IV ($37 million).

Figure 3

Summary of Changes in Child Welfare Spending

(In Millions)

|

2020‑21 revised |

2021‑22 Governor’s Budget |

Change |

||||||

|

Federal Funds |

State General Fund |

Federal Funds |

State General Fund |

Federal Funds |

State General Fund |

|||

|

Temporary FMAP increase |

$139 |

— |

$70 |

— |

‑$68 |

— |

||

|

Supplemental Title IV‑B funds |

5 |

— |

— |

— |

‑5 |

— |

||

|

Family First Transition Act |

295 |

— |

129 |

— |

‑166 |

— |

||

|

State pandemic response |

— |

$85 |

— |

$61 |

— |

‑$24 |

||

|

Placement Prior to Approval |

10 |

32 |

5 |

15 |

‑6 |

‑17 |

||

|

One‑time state funds to counties |

— |

80 |

— |

— |

— |

‑80 |

||

|

HBFC rates |

103 |

211 |

111 |

227 |

8 |

17 |

||

|

Other CCR expenditures |

29 |

76 |

30 |

81 |

1 |

4 |

||

|

FFPSA Part IV implementation |

— |

— |

18 |

43 |

18 |

43 |

||

|

Other changes |

— |

— |

— |

— |

208 |

9 |

||

|

Totals |

‑$9 |

‑$48 |

||||||

|

FMAP = federal medical assistance percentage; HBFC = home‑based family care; CCR = Continuum of Care Reform; and FFPSA = Family First Prevention Services Act. |

||||||||

Pandemic Response Would Continue. In the weeks following the state and federal emergency declarations in response to coronavirus disease 2019, the state authorized funding in 2019‑20 for several measures to provide pandemic support to families within the child welfare system. Figure 4 summarizes these actions in addition to new action the administration has proposed as part of its 2021‑22 budget proposal.

Figure 4

State Funds for Pandemic Response Within Child Welfare Programs

(In Thousands)

|

2019‑20a |

2020‑21b |

2021‑22c |

|

|

Cash cards for families at risk of foster care |

$27,842 |

$28,000 |

— |

|

Family Resource Centers funding |

3,468 |

7,000 |

$6,000 |

|

State contracts for technology (laptops and cell phones) and hotlines for foster youth and familiesd |

— |

2,042 |

1,750 |

|

Administrative workload for child welfare social workers (overtime and pandemic outreach) |

5,000 |

— |

— |

|

Rate flexibilities for resource families directly impacted by pandemic |

3,005 |

9,136e |

3,458 |

|

Flexibilities and expansions for NMDs/former NMDs who turn 21 or lose otherwise lose eligibility for EFC due to pandemic |

1,846 |

37,133 |

49,487 |

|

Pre‑approval funding for emergency caregivers beyond 365 days |

1,312 |

1,234 |

— |

|

Totals |

$42,473 |

$84,545 |

$60,695 |

|

aFor 2019‑20, funds were provided April through June 2020. Activities were approved by the Legislature through the Section 36.00 letter process. bFor 2020‑21, pandemic‑response activities are proposed by the administration for January through June 2021 for all actions other than flexibilities and expansions for NMDs. The Legislature has not yet approved these activities for 2020‑21, with the exception of flexibilities and expansions for NMDs, which were included in the 2020‑21 Budget Act and are in place July 1, 2020 through June 30, 2021. cFor 2021‑22, funds are proposed by the administration for July through December 2021. dFunding for state contracts for technology and hotlines in 2019‑20 is included in the amount for Family Resource Centers funding. eIncludes $5.678 million funding from DREOA. Note: Where applicable, amounts include assistance plus administration costs. |

|||

|

NMD = non‑minor dependents; EFC = extended foster care; and DREOA = Disaster Response Emergency Operations Account. |

|||

We note that 2019‑20 funding ended June 30, 2020. For all 2020‑21 actions other than flexibilities and expansions for NMDs, funding amounts listed in the figure reflect new proposals from the administration as part of the 2020‑21 revised budget at the time of the 2021‑22 Governor’s Budget proposal. The administration has indicated the proposed activities would begin in January 2021. Therefore, we note that there appears to be a funding gap between July 2020 and January 2021. We are currently working with the administration to better understand what actions (if any) counties have been able to take to continue these pandemic supports in the interim, and what authority and communication is needed for counties to continue (or re‑launch) these supports for youth and families in 2020‑21. At this point, the administration has not provided any details as to how these proposals would be authorized in the current year.

Implementation of FFPSA Part IV Would Begin. As noted earlier, states are required to come into compliance with the congregate care provisions stipulated by Part IV of FFPSA by October 1, 2021. If not in compliance by that time, states will lose federal funding for congregate care placements. As part of ongoing CCR, California already has made changes to congregate care that position the state ahead of many others in terms of coming into compliance with FFPSA Part IV. Namely, California has made significant progress toward reducing reliance on congregate care, instead providing more supports and services to youth in resource family placements and more independent living placements, and providing intensive services through STRTPs when a youth cannot safely be placed in a resource family home. As such, CCR efforts run parallel to the goals of FFPSA Part IV’s congregate care reforms, which aim to ensure the appropriateness of all congregate care placements, reduce long‑term congregate care stays, and facilitate stable transitions to home‑based placements. Nonetheless, the state will need to make changes to ensure compliance with FFPSA’s congregate care facility licensing standards and placement criteria.

To meet FFPSA Part IV requirements, we understand the administration intends to propose implementing legislation. While the language was not yet available at the time of publication, we understand the Governor’s budget proposal includes the following elements:

- Guaranteed Access to Nursing Care. FFPSA requires STRTPs to have 24/7 access to nursing care. To meet this requirement, the administration proposes to contract with and fund a virtual telehealth hotline, facilitating interaction between STRTPs and nurses at any time.

- QI Assessment of Congregate Care Placements. FFPSA requires a qualified individual (QI), who is medically certified, to assess and report on the appropriateness of all STRTP placements. The administration’s plan includes funding for QIs to participate in CFTs, conduct the Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths (CANS) assessment, and prepare required court documentation for all STRTP placements.

- Access to Aftercare Services. FFPSA requires at least six months of specified support services for youth and families after a youth exits a congregate care placement. The administration’s proposal includes funds to provide aftercare services for at least seven months for youth transitioning from an STRTP to a family‑based care setting.

- Court‑Related Activities. FFPSA requires enhanced assessment and reporting around congregate care placements. As such, social workers will need to spend additional time on court‑related activities, such as attending additional hearings and completing supplemental reports for STRTP placements. The administration’s proposal includes funding for these increased social worker costs.

- Judicial Branch Training. FFPSA requires states to train judges and other court staff on child welfare policies, including federal funding limitations for out‑of‑home foster placements. The administration proposes to pass Title IV‑E funds through to the state’s Judicial Council for this required training.

- Placement Assessment Evaluation and Review. In California, CFTs use the CANS assessment to determine placements. To implement FFPSA, the administration proposes that QIs will participate in CFTs and also will use the CANS tool to assess the appropriateness of congregate care placements. The administration proposes to establish an ongoing external contract and funding to evaluate CANS data for placement assessments.

- Various Training. Finally, the administration’s proposal includes funding for various FFPSA training costs, including training for: QIs on CFTs and CANS procedures, providers on developing and implementing aftercare services, and social workers on new federal provisions.

FFPSA Part I Option for Counties May Be Included in Proposed Legislation. As we noted earlier, once states comply with FFPSA Part IV’s congregate care provisions, Part I affords states the option of using Title IV‑E dollars for certain services and activities aimed at preventing entry into foster care. At the time of publication, whether the administration intends to propose legislation allowing counties to exercise these flexibilities was unclear. We note that General Fund dollars are not included in the Governor’s budget for this purpose, meaning if FFPSA Part I implementation legislation were proposed, it likely would be optional and counties would need to provide the required matching funds using their realignment revenues or other county sources to be able to claim additional federal Title IV‑E dollars.

Proposes Maintaining Program Suspensions Calculation. Under current law, several child welfare programs would be subject to suspension after December 31, 2021 if the Department of Finance found there would not be sufficient revenues to support them at the time of the 2021‑22 May Revision. (Under both our office’s revenue estimates and those by the Department of Finance, there would be sufficient revenues to support the programs and the suspension would not take effect.) The 2021‑22 Governor’s Budget proposes to maintain the suspension calculation for the 2021‑22 budget. Figure 5 lists the child welfare programs on the suspension list. We provide a more detailed overview of suspensions in our office’s recent publication on the topic here.

Figure 5

Child Welfare Programs Subject to Suspension

General Fund (In Millions)

|

Program Subject to Suspension |

Annual Cost of Program, |

|

Family Urgent Response System |

$30 |

|

Public health nursing early intervention pilot program in Los Angeles County |

8 |

|

Emergency Child Care Bridge program supplement |

10 |

|

Foster Family Agency social worker rate increase |

7 |

|

Transitional Housing Program grants to counties for former foster youtha |

8 |

|

aProgram administered by the California Department of Housing and Community Development. All other programs administered by the Department of Social Services. |

|

LAO Comments and Questions for the Legislature to Consider

Continued Implementation of CCR: What Is the Status of CFTs, CANS, and LOC Protocol Tool? We are working with the administration to understand what underlying assumptions it made for the 2021‑22 budget proposal around continued implementation of certain CCR elements, namely the LOC protocol tool, CFTs, and CANS assessments. We understand that these elements have yet to be fully implemented. If the Governor’s budget proposal assumes full implementation will occur in 2021‑22, actual expenditures may be lower than budgeted to the extent that there are implementation delays, and resulting savings could be directed toward other legislative priorities. The Legislature may wish to ask the administration to provide CCR implementation updates during upcoming hearings to better understand any potential savings. For example:

- What is the status of CFT implementation? How many CFTs occurred in 2020? Are counties on track to achieve universal usage of CFTs in 2020‑21 or 2021‑22?

- What is the status of CANS implementation? How many CANS assessments were completed in 2020? Are counties on track to achieve universal usage of CANS in 2020‑21 or 2021‑22?

- What is the status of LOC protocol tool implementation? Are there plans to roll out the tool beyond FFAs in 2020‑21 or 2021‑22?

Recommend Allowing Extension for Funding for Emergency Caregivers Prior to RFA. As we expressed during the previous budget cycle, we remain concerned that statute dictates funding for pre‑approval funding will decrease to 90 days—without any option for extension—while average RFA processing time continues to exceed 90 days. This statutory time limit change will result in emergency caregivers losing access to foster payments if they experience delays in the RFA process—even when delays are beyond their control. We recommend the Legislature consider changing statute to continue to allow for good cause extension on an ongoing basis, especially during a pandemic.

Questions About Pandemic Response Proposals. As described above, initial state funding (provided in April 2020) for several pandemic response activities within child welfare appears to have ended in June 2020. At the time of the 2021‑22 Governor’s Budget proposal, the administration proposed new child welfare pandemic response spending in 2020‑21 and 2021‑22.

In upcoming hearings, the Legislature may wish to ask the administration to provide more information about its new proposals for 2020‑21. For example:

- For components that ended June 30, 2020 (or some other date in 2020)—what has been happening since then? Have counties continued exercising flexibilities using local funds?

- Considering the Legislature has not yet approved these actions, the funding mechanism for newly proposed 2020‑21 pandemic response remains unclear. What funding mechanism does the administration propose to use for newly proposed activities in the current year?

- The administration proposed that counties could begin activities in January 2021. Did this occur? What guidance has been provided or will be provided to counties to ensure they are able to provide the proposed supports in 2020‑21?

Additionally, for pandemic response activities proposed to continue into the 2021‑22 budget year, the administration’s proposed funding would end midyear (December 31, 2021). The Legislature may wish to ask the administration to provide more information about:

- If pandemic resources are needed beyond December 31, 2021, what action would be needed to continue supports? Projecting the course of the pandemic, and predicting what needs children and families will have, is difficult and some continued flexibilities may be needed.

- Regarding support for NMDs and former NMDs, when expansions and flexibilities end in December, will youth who become ineligible to remain in EFC be able to transition successfully? What supports will be provided to help youth prepare for the transition into independence?

Finally, the Legislature may wish to examine whether alternative pandemic support proposals within child welfare should be considered, either in addition to or instead of some of the administration’s proposals. For example, the Legislature could consider providing temporary direct support for resource families and/or STRTPs through monthly rate supplements. Such supplemental payments could assist caregivers and providers with the higher costs of providing foster care during the pandemic (like for food and utilities), and help mitigate other adverse economic impacts caregivers and providers may be facing. For example, providing an additional $200 for each of the estimated 46,000 foster youth placed with resource families (including emergency caregivers) and in STRTPs would cost around $9.2 million per month.

Questions About FFPSA Part IV Proposal. As described above, the administration proposes funds to implement Part IV of FFPSA, as required by October 1, 2021, in order to retain federal funding for congregate care placements. We understand the administration intends to propose legislation to establish the new program elements and guide their implemention. At the time of publication, this legislation was not yet available. We are currently working with the administration to understand additional details and time lines around FFPSA Part IV implementation. In upcoming hearings, the Legislature may wish to request additional detail from the administration to determine the feasibility of meeting the October 1 federal deadline. For example:

- Are STRTP providers prepared to begin using the telehealth hotline, facilitating aftercare services, and meeting other requirements? What training and technical assistance do STRTP providers need, and what is the time line?

- Are STRTP providers expected to provide aftercare services directly, or contract with a third party to provide the required care?

- QIs play an important role in ensuring congregate care placements are necessary and meeting new federal reporting requirements. Who would be QIs? How would these individuals be selected? What would be the time line for selecting and training QIs?

- The administration proposes that QIs will participate in CFTs and use CANS assessments to determine the necessity of STRTP placements. If these components of CCR have not been fully rolled out by October 1, what alternative processes and tools would QIs use?

Consider Trade‑Offs of Allocating State Funds for FFPSA Part I Implementation. At the time of publication, whether the administration also intends to propose legislation allowing counties the option of claiming Title IV‑E dollars for newly allowed services and activities aimed at preventing entry into foster care remained unclear. The administration does not include any General Fund dollars for implementation in the 2021‑22 Governor’s Budget. Therefore, if the administration does intend to introduce FFPSA Part I legislation, we understand newly allowed activities would be county options, and counties would be able to use local funding for these activities at their discretion. Implementing FFPSA Part I as a county option without any state support raises potential equity concerns. Namely, some counties may not implement optional activities due to local budget constraints or differing local priorities. As a result, families in different counties may receive different levels of service and some children may not receive the benefits of these programs and therefore could be more likely to enter foster care.

To the extent that the Legislature would like to prioritize prevention activities and ensure families at risk of entry into the foster care system benefit from new uses of Title IV‑E dollars regardless of their county, the Legislature may wish to consider a General Fund appropriation for counties to begin to implement foster care prevention activities under FFPSA. Any augmentation would be matched by federal funds, thereby roughly doubling the fiscal impact, and also potentially could reduce the costs of foster care over time by preventing entries. To further explore this issue, the Legislature may wish to ask the administration:

- Without state resources, how would the administration ensure that all families throughout the state have access to prevention programs?

- Could the existence of prevention programs in some counties and not in others create equity concerns?

- Could providing funding for prevention programs ultimately lead to overall savings to the child welfare system?

- Has the administration considered creating a loan program or providing one‑time start‑up funding for counties interested in starting prevention programs but limited by their own fiscal constraints?

Recommend Rejecting Child Welfare Program Suspensions. Our office recently published an assessment of the Governor’s overall suspension proposal, which includes a few child welfare programs, as described in the preceding section of this post. We recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal to create new budget bill suspension language—thereby likely establishing the programs on an ongoing basis—but evaluate the merits of some of the newer programs’ reporting and oversight to ensure programmatic design aligns with legislative policy objectives and that the programs are resulting in the intended outcomes. The complete analysis may be accessed on the LAO’s website here.