LAO Contact

February 17, 2021

The 2021-22 Budget

Behavioral Health:

Continuum Infrastructure Funding Proposal

This budget series post provides (1) an overview of the Governor’s budget proposal in the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) to provide $750 million General Fund—on a one‑time basis—in competitive grants to counties to acquire or renovate facilities for community behavioral health services, (2) an assessment of the Governor’s proposal, and (3) key takeaways from our assessment of the proposal that raise issues for Legislative consideration. We understand the administration’s proposed budget bill language for this proposal is forthcoming. This analysis reflects our understanding of the proposal as of February 17, 2021.

This budget post is one in a series of posts that we are releasing on major behavioral health‑related proposals. In separate posts, we analyze the Governor’s proposals to (1) provide incentive payments through Medi‑Cal managed care for student behavioral health and (2) establish an additional demonstration project in which a select number of counties would assume responsibility for treating felony Incompetent‑to‑Stand‑Trial patients.

Background

County Behavioral Health Facilities

In California, Public Community Behavioral Health Services Primarily Are Funded and Delivered Through Counties. Counties play a major role in the funding and delivery of public behavioral health services. In particular, counties generally are responsible for arranging and paying for community behavioral health services for low‑income individuals with the highest service needs. Community behavioral health services comprise publicly funded outpatient and inpatient mental health and substance use disorder treatment and medications provided primarily in community settings.

Counties Can Use a Variety of Funding Sources for Community Behavioral Health Facilities. Counties rely on a variety of major, dedicated, ongoing fund sources to finance their community behavioral health activities including facilities. These sources include (1) dedicated vehicle license fee and sales tax revenue streams known as “realignment” funds, (2) revenues from the Mental Health Services Fund (MHSF)—funded through a 1 percent tax on incomes over $1 million, and (3) federal funding accessed through Medi‑Cal (California’s state Medicaid program). Although each of these funding sources has its own set of objectives and rules dictating how funds can be spent, there is sufficient overlap in purpose between these funding sources for counties to use them flexibly to meet their community behavioral health service obligations. Notably, funding that counties receive from the MHSF is required to be spent according to certain parameters, including (1) direct services and (2) prevention and early intervention activities. Up to 20 percent of the amount counties receive from the MHSF for direct services can be used on capital (including facility acquisition and renovation), technology, workforce development, or to build reserve funding. However, the amount within this allowance (and of counties’ overall behavioral health funding) that counties spend on acquiring or renovating community behavioral health facilities is unknown.

State Grant Programs for County Behavioral Health Facility Acquisition. In recent years, the state created limited‑term grant programs for the acquisition of infrastructure for community behavioral health facilities by counties. We describe these grant programs, some of which have expended all available funds and some of which still have funds available, below.

- Creation of Mental Health Wellness Act of 2013 Grant Program. Chapter 34 of 2013 (SB 82, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) provided $142.5 million from the General Fund on a one‑time basis to provide grants to counties to acquire facilities for community mental health services. This grant program was administered by the California Health Facilities Financing Authority (CHFFA). Under the program, counties could use the vast majority of this funding to establish mental health crisis facilities, which are intended for short‑term treatment while an individual is experiencing a mental health crisis. Of the total made available, $136.5 million in grant funds were awarded to counties.

- Later Augmentation of 2013 Grant Program for Children‑ and Youth‑Related Facility Acquisition. The Investment in Mental Health Wellness Act of 2013 Grant Program was amended in 2016‑17 to include additional funding and a specific focus on acquiring facilities for youth mental health crisis facilities. (A portion of the funds that were not awarded to counties under the first iteration of the grant program was redirected to this purpose.) In total, $24.9 million was made available for acquiring community mental health facilities under this iteration of the grant program. All of this funding is still available.

- Community Services Infrastructure Grant Program. Chapter 33 of 2016 (SB 843, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) established the Community Services Infrastructure Grant Program, providing $65.8 million General Fund one‑time as part of the 2017‑18 budget. This program made grants available to counties for behavioral health infrastructure (including facility acquisition) to support efforts to divert individuals from incarceration. The program also was administered by CHFFA. All available grant funds under this program have been disbursed to counties.

- No Place Like Home (NPLH) Program. In November 2018, voters approved Proposition 2, authorizing the sale of up to $2 billion of revenue bonds (and the use of a portion of revenues from the MHSF to repay the bonds) for the NPLH program. The program funds permanent supportive housing for individuals experiencing homelessness who also struggle with mental illness. Under this program, counties applying for funds must commit to provide mental health services and help coordinate access to other community‑based supportive services for permanent supportive housing residents. This program is administered by the Department of Housing and Community Development as a competitive grant program for counties. About $1.4 billion has been made available to counties through NPLH so far, and most of this amount has been awarded.

State Capacity for Behavioral Health Crisis Services

While a comprehensive assessment of overall behavioral health service capacity statewide is not available currently, data do indicate that the supply of inpatient beds for severe mental health crises is not meeting the state’s needs. In addition, the amount of community behavioral health crisis services needed may grow in the future. We describe these two points below.

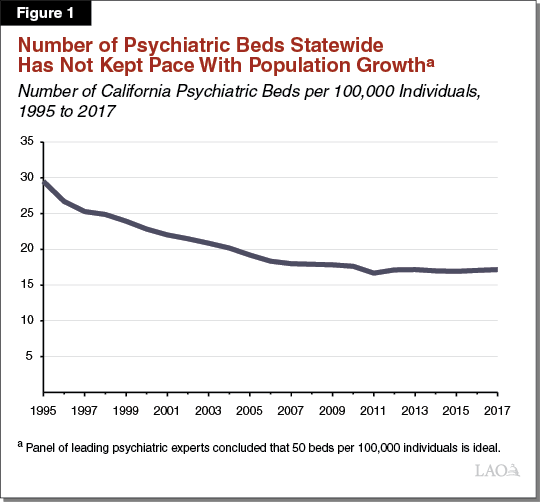

Number of Psychiatric Beds Statewide Has Not Kept Pace With Population Growth and Demand. The most commonly cited figure for the appropriate number of inpatient psychiatric beds per population comes from the Treatment Advocacy Center, which convened a panel of leading experts who concluded that 50 beds per 100,000 individuals is the ideal bed capacity to serve demand. California historically has not met this standard, and notably was performing worse on this metric in 2017 (the most recent year for which data are available) than it was in 1995. Figure 1 illustrates California’s historical performance on this metric.

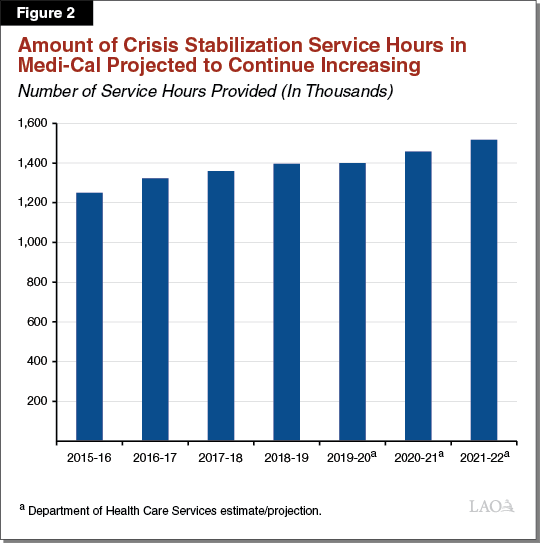

Medi‑Cal Mental Health Crisis Service Hours Projected to Continue Increasing. When an individual is experiencing a severe mental health crisis, a Crisis Stabilization Unit (CSU) can be a valuable setting in which to provide treatment. CSUs generally are small inpatient facilities for people experiencing a severe mental health crisis whose needs cannot be met safely in residential settings. Counties provide CSU services as part of their Medi‑Cal responsibilities. Recent DHCS projections (based on historical utilization trends) expect mental health crisis stabilization service hours in the Medi‑Cal program to be 20 percent above their 2015‑16 level by 2021‑22. Figure 2 illustrates this projected growth in crisis stabilization service hours provided in the Medi‑Cal program.

CSUs Can Provide Alternative to Psychiatric Beds... Community behavioral health facilities (such as CSUs) can provide an alternative to inpatient psychiatric stays. For example, individuals experiencing a severe mental health crisis can be admitted to a CSU to be stabilized to avoid hospitalization.

…But Number of CSU Beds Per Population Currently Is Low. Given that the number of inpatient psychiatric beds per population in California is very low, an expansion of CSU capacity can help absorb the demand for intensive behavioral health services. However, the state currently has just 1 CSU bed per 100,000 individuals.

Governor’s Proposal

$750 Million General Fund One Time for Counties to Acquire or Renovate Behavioral Health Facilities. The Governor’s budget proposes $750 million General Fund on a one‑time basis (available for three years) to provide competitive grants to counties to acquire or renovate facilities for community behavioral health service delivery. The administration intends for this proposal to help build out a comprehensive continuum of care for individuals with varying levels of behavioral health needs, and envisions that this proposal will complement related state priorities such as reducing homelessness. This grant program would be administered through DHCS. The administration estimates that this proposal will add at least 5,000 beds for behavioral health treatment statewide.

Funding Could Be Used on a Variety of Facility Types. Under the Governor’s proposal, counties would be able to use grant funds on a variety of community behavioral health facility types to treat individuals with varying levels of behavioral health needs. Funds could be used on (1) short‑term treatment beds such as those found in CSUs, (2) residential treatment facilities that typically last for a few months, or (3) longer‑term facilities such as permanent supportive housing for individuals with behavioral health needs. Notably, funding from this proposal could be used for both mental health and substance use disorder treatment facilities. (This is in contrast to several of the existing and prior state grant programs discussed earlier, which focused on mental health facilities specifically.)

Counties Would Be Required to Provide Matching Funds. Under this proposal, counties would be required to provide matching funds—in the amount of 25 percent of grant funds—in order to receive grant funding. This match can take a variety of forms, including in‑kind contributions (such as land), philanthropic donations, and other funding sources of the county’s choosing (such as county funds). In addition, in order to receive funds, counties would have to identify an ongoing funding amount to support costs related to operating potential facilities and commit to operating potential facilities for a period of 30 years.

Other Related Governor’s Budget Proposals. Below, we describe the interaction between the behavioral health continuum infrastructure funding proposal and two other major items from the Governor’s budget.

- CalAIM SMI/SED Demonstration Opportunity Commitment. The Governor’s budget re‑introduces the California Advancing and Innovating Medi‑Cal (CalAIM) proposal, a far‑reaching set of reforms to expand, transform, and streamline Medi‑Cal service delivery and financing. The CalAIM proposal includes a commitment from the administration to pursue a federal waiver opportunity—known as the SMI/SED demonstration opportunity—to potentially receive federal reimbursement for services provided to individuals with Severe Mental Illness (SMI) and/or Severe Emotional Disturbance (SED) that are normally not eligible for federal funding. In order to gain approval from the federal government for this waiver opportunity, the state will need to build out necessary behavioral health infrastructure. While the behavioral health continuum infrastructure funding proposal is not explicitly required to gain approval for this waiver demonstration opportunity under CalAIM, the administration has indicated that the proposal may be seen as complementary to the commitment to pursue the SMI/SED demonstration opportunity. (The administration believes this proposal will help the state build out the necessary infrastructure to gain waiver approval from the federal government for this demonstration opportunity.) Please see our budget post, The 2021‑22 Budget: CalAIM: The Overarching Issues, for a more detailed description of this component of the CalAIM proposal.

- Efforts to Address Homelessness. The Governor’s budget includes a package of proposals intended and designed to address the state’s homelessness problem. The budget also includes a number of proposals in various other policy areas that can be viewed as having some overlap with efforts directly addressing the state’s homelessness issues. The administration has indicated that the behavioral health continuum funding proposal can be thought of as one component of the state’s broader efforts in this area. Please see our budget handout, The 2021‑22 Budget: Analysis of Housing and Homelessness Proposals, for a description of the various Governor’s budget efforts to reduce homelessness.

Assessment and Issues for Legislative Consideration

Further Specifics of the Proposal Needed to Fully Assess Its Merits. Further details are necessary to fully evaluate this proposal. These details would include specifics about (1) the structure of the grant program (for example, what specific milestones counties will have to meet to receive disbursement of grant awards), (2) how funds available to counties through the grant program will be targeted to regions of the state that experience more substantial shortages of behavioral health beds, and (3) what oversight and evaluation activities DHCS will conduct for the grant program. Our understanding is that budget bill language is forthcoming, however, trailer bill language will not be proposed.

Lack of Implementing Legislation Raises Concerns and Questions. While this proposal likely has merit, budget bill language is insufficient for establishing a new program of this magnitude. Prior grant programs to provide funding to counties for behavioral health facilities—which also were developed through the budget process—included trailer bill language to specify legislative intent and the terms of the programs. Moreover, recent one‑time allocations for homelessness grants to local governments like the Homelessness Emergency Aid Program; Homeless Housing, Assistance, and Prevention Program; and Homekey all included trailer bill language to govern those allocations. Typically, budget bill language has much less specificity than a trailer bill language. We suggest the Legislature adopt trailer bill language to govern the implementation of this program and provide more opportunities for oversight—like through reporting to the Legislature on grant allocations. Without authorizing legislation, the Legislature’s ability to effectively oversee the program and hold local governments accountable would be significantly constrained.

Available Data Indicate Expanding Capacity for Behavioral Health Services Likely Has Merit. As discussed earlier, the administration projects growth in short‑term mental health crisis services in the Medi‑Cal program. In addition, the number of inpatient psychiatric beds available statewide relative to population indicates that the supply of these beds in California likely is not meeting the state’s needs. The number of facilities that can provide short‑term mental health crisis services as an alternative to inpatient psychiatric beds also is low. Together, these factors demonstrate that an expansion of capacity for community behavioral health services (through securing additional facilities) likely is warranted.

Proposal Would Be Significant One‑Time Support. Most funding to counties for community behavioral health services is provided on an ongoing basis through dedicated funding streams. As noted above, however, the state recently made efforts to expand facility capacity by providing multiple one‑time grant programs. Given the state’s significant one‑time windfall, using those resources for a one‑time grant program for behavioral health facilities likely is a good investment. If, however, the Legislature expects to continue this approach for supporting community behavioral health services in the future, setting clear goals and metrics will be important to ensure a strategic allocation of available one‑time resources to address underlying challenges.

Proposal Provides Funding for Several Facility Types Also Supported by Other Funds. Although the specific amount counties spend to acquire community behavioral health facilities is unknown, in concept, counties could use a portion of the ongoing funding they receive for community behavioral health services to fund similar activities as this proposed grant program. In concept, this proposal could free up county funds—that would otherwise be spent on acquiring facilities—to expand county behavioral health service capacity.

In addition, while the list of community behavioral health facility types this proposal would fund do not perfectly overlap with the facility types that can be funded through existing state grant programs, there are some commonalities. Specifically, this proposal makes grant funding available for (1) crisis stabilization and crisis residential facilities, which can also be funded through the augmentation for children and youth made to the Investment in Mental Health Wellness Act of 2013 Grant Program, and (2) permanent supportive housing for individuals with mental health needs, which can also be funded through the NPLH program. These commonalities across grant programs create opportunities to apply lessons learned, which we describe below.

Overlap With State Grant Programs Provides Opportunity to Apply Lessons Learned. There are several key lessons learned from challenges experienced in prior grant programs. Our review finds that counties have experienced difficulty meeting program requirements for state facility grant programs, which has led to (1) delays in funds disbursement, (2) forfeiture of grant funds in cases where counties determined that securing facilities was no longer feasible, and (3) reduced interest in applying for facility grant funds. Some key lessons learned include:

- Under the Investment in Mental Health Wellness Act of 2013 grant program, counties originally were intended to be the sole entity to receive grant funds directly for acquiring or renovating facilities. However, counties generally did not have sufficient technical expertise in acquiring health facilities to proceed with grant program requirements effectively, which led to significant delays in disbursement of grant funds. The grant program later was adjusted to allow counties to designate a third party—usually a nonprofit or corporation—to directly apply for and receive grant funds on counties’ behalf. This led to more success in getting funds disbursed. Under the behavioral health continuum infrastructure funding proposal, counties would be allowed to contract with a nonprofit provider to operate potential facilities, but the extent to which these entities will be involved in the application process or receive grant funds directly is unclear. Including this third‑party component into the behavioral health continuum infrastructure funding proposal as was ultimately added to the 2013 grant program could help avoid the significant delays in getting funds disbursed to counties experienced by existing and prior programs. If this option is not built into the proposal, then very robust technical assistance would be needed to help counties—especially small and rural ones—navigate grant program application processes and requirements. Given this lesson learned, the Legislature may wish to consider which entity—counties versus nonprofits or corporations—would be most appropriate to be responsible for directly applying for and receiving grant funds.

- Counties also have experienced challenges related to local opposition of the siting of community behavioral health facilities. The Legislature may wish to ask the administration what the state‑level strategy for navigating local opposition would be. Elements of this strategy could include (1) a requirement that counties demonstrate community engagement related to their grant‑funded activities, or (2) exploring ways to streamline local approval processes so as not to inhibit the establishment of community behavioral health facilities.

- Under the funding augmentation for children‑ and youth‑related facility acquisition provided to the Investment in Mental Health Wellness Act of 2013 grant program, there has been reduced demand among counties for the program due to accelerated time lines for putting together application materials. The Legislature may wish to ask the administration (1) how long counties would have to submit their applications for grant funding, and (2) how the administration would work with counties to ensure they are able to meet any deadlines outlined under the grant program.

Proposal Could Address Some Concerns About CalAIM SMI/SED Demonstration Opportunity. Historically, the state has favored placement in community settings for mental health treatment over placement in institutional settings, in keeping with the principle of providing mental health care in the least restrictive setting possible. One of the requirements for the state to obtain approval for the CalAIM SMI/SED demonstration opportunity would be to demonstrate to the federal government that the state is committed to maintaining support for, and potentially enhancing, community behavioral health treatment service capacity. This requirement is meant to ensure that additional federal funding provided for mental health services rendered in institutional settings does not incentivize institutional placement beyond what is absolutely necessary. The activities funded by this proposal—acquisition of additional behavioral health facilities—could be considered by the federal government as evidence of this commitment and help contribute to the state’s application for this demonstration opportunity. Given the interaction between this proposal and the SMI/SED demonstration opportunity under CalAIM, the Legislature may wish to weigh the increased community behavioral health service capacity that this grant program could provide against any concerns that it may have about unintended consequences from the state gaining approval for the SMI/SED demonstration opportunity.

How Proposal Would Be Targeted at Individuals Experiencing Homelessness Is Unclear. This proposal is specifically intended to increase counties’ capacity to provide behavioral health services. While there are many individuals experiencing homelessness who also have significant behavioral health needs, these populations do not fully overlap. Accordingly, how funding for this proposal would be targeted for individuals experiencing homelessness is unclear. Funding provided under the NPLH program is specifically earmarked for individuals struggling with mental illness who also experience homelessness. Without a similar targeting of funds, whether this proposal would address the state’s homelessness issues directly is uncertain. The Legislature may wish to use the budget process to inquire about overlap and coordination with the administration’s other budget proposals related to homelessness.

Counties’ Capacity to Fund Ongoing Costs Related to Maintenance and Services Unclear. Funding for this proposal is intended to be provided on a one‑time basis. Accordingly, counties would be responsible for funding (1) the ongoing costs associated with maintenance of acquired behavioral health facilities and (2) the ongoing costs to provide services in the acquired facilities. Although this proposal would require that counties identify ongoing funding to cover these costs (and commit to providing ongoing funding for 30 years), counties’ capacity to increase their funding levels to pay for such new ongoing costs without displacing existing activities is unclear.

Further Details on Proposed County Match Requirement Needed. The administration has indicated that counties will be required to provide a 25 percent match in order to receive grant funds under this proposal. (In contrast to other state grant programs for behavioral health facilities which did not include a county match requirement—beyond the NPLH program’s requirement that counties commit to providing ongoing support for residents in permanent supportive housing.) While a local match requirement can help ensure that counties demonstrate a commitment to the activities of this grant program, how the 25 percent match was determined is unclear. Given that this proposed match requirement may affect county demand to apply for grant funding under this proposal, the Legislature may wish to seek further details from the administration about how the county match requirement was determined and whether counties have the capacity to meet it.