LAO Contact

February 19, 2021

The 2021-22 Budget

Behavioral Health:

Community Care Demonstration Project

This budget series post provides (1) an overview of the Governor’s budget proposal to provide $233.2 million General Fund in 2021‑22 and $136.4 million General Fund in 2022‑23 and ongoing for the Department of State Hospitals (DSH) to establish a demonstration project—that would be optional for counties to participate in—in which responsibility for treating individuals found incompetent to stand trial (IST) facing a felony charge would be realigned to participating counties, (2) an assessment of the Governor’s proposal, and (3) our recommendations on this proposal.

This budget post is one in a series of posts that we are releasing on major behavioral health‑related proposals. In separate posts, we analyze the Governor’s proposals to (1) provide grant funds to counties to acquire and renovate behavioral health facilities and (2) provide incentive payments through Medi‑Cal managed care for student behavioral health.

Background

Felony ISTs and the Waitlist. Currently, counties are responsible for almost all mental health treatment for low‑income Californians with severe mental health needs. One exception, however, is treatment for individuals found IST and who face a felony charge (we refer to these individuals as “felony ISTs”). The state treats almost all felony ISTs in state hospitals; however, many individuals wait in county jails for many months given the limited number of DSH beds, which has resulted in a waitlist of felony ISTs who have not been admitted to DSH. The treatment provided to felony ISTs—known as “competency restoration treatment”—differs from general mental health treatment. The objective of competency restoration treatment is to treat a felony IST until he or she is competent enough to face their criminal charge, rather than provide comprehensive treatment for his or her underlying mental health condition. While the state is responsible for treating felony ISTs, counties are responsible for treating misdemeanor ISTs.

DSH Received Funding Augmentations in Prior Years to Treat Felony ISTs, Including Through Contracts With Counties. To increase capacity for felony IST treatment, in prior years, DSH has received funding to both (1) expand bed capacity in state hospitals and (2) contract with counties to provide competency restoration treatment to felony ISTs who do not require the higher level of care that state hospitals provide. When contracting with counties, DSH still retains responsibility for felony IST treatment, but provides funding to counties to treat felony ISTs on its behalf. County‑provided IST felony treatment includes (1) the establishment of Jail‑Based Competency Treatment (JBCT) programs in which competency restoration treatment is provided to felony ISTs while they are in county jails and (2) Community‑Based Restoration (CBR) programs, in which counties receive funding to provide competency restoration treatment in a variety of community behavioral health treatment settings. Figure 1 describes these county‑operated programs.

Figure 1

County‑Operated Felony IST Treatment Programs

|

Program |

Year |

2018‑19 |

Felony ISTs |

|

Jail‑Based Competency Treatment |

2007‑08 |

$59.8 million GF |

1,739 |

|

Community‑Based Restoration |

2018‑19 |

$15.6 million GF |

165 |

|

IST = incompetent to stand trial and GF = General Fund. |

|||

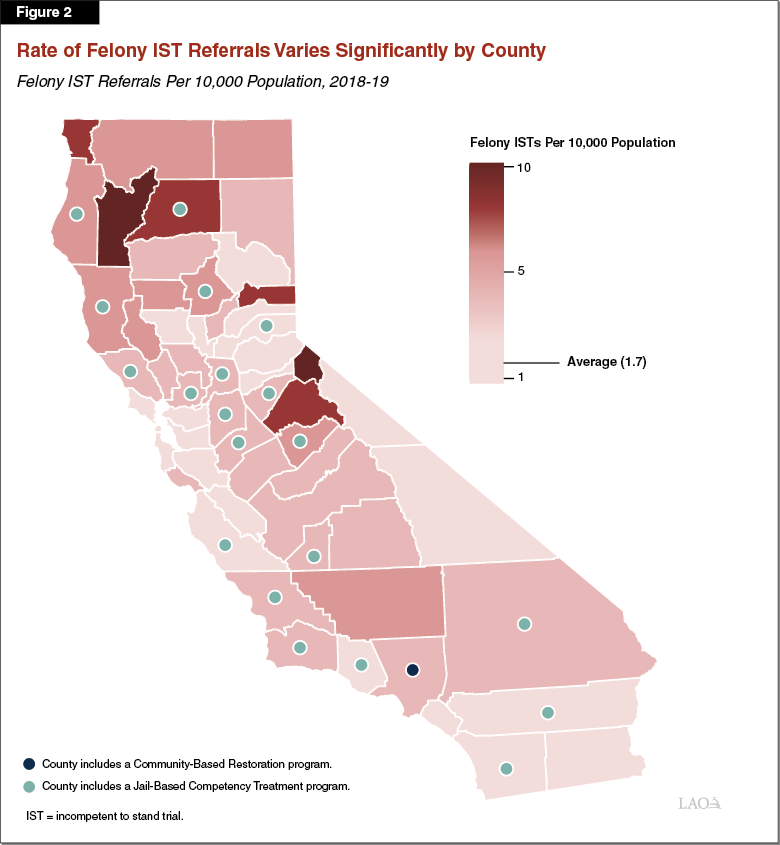

Some County Contracts in Place in Regions Where Referral Rates Are Highest. There is significant variation by county in the rate of felony IST referrals for competency restoration, as shown in figure 2 in 2018‑19. (We use 2018‑19 data because this is the most recent full year of data that precedes any pandemic‑related changes to the process of referring felony ISTs to treatment.) Prior‑year efforts to provide funding for county‑based treatment have tried to provide more competency restoration treatment options for felony ISTs. In some cases, these county‑based treatment options have been established in counties with relatively high rates of IST referrals. Importantly, counties can send felony ISTs to other counties’ competency restoration programs. Accordingly, counties with high rates of felony IST referrals that do not operate programs are typically located adjacent to counties that do.

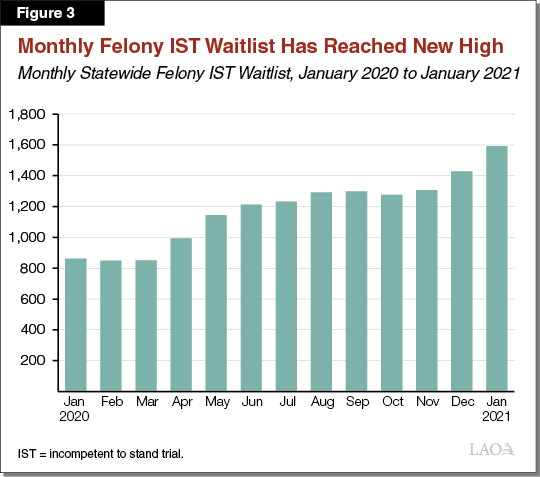

Felony IST Waitlist Has Reached New High, in Part Due to COVID‑19 Restrictions. Prior to the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) pandemic, the number of felony ISTs on the waitlist for competency restoration was typically around 800 individuals (with an average wait time exceeding 100 days). Since the initial months of the pandemic, the number of felony ISTs on the waitlist has grown to about 1,600 individuals as of January 2021. This increase predominantly is attributed to (1) DSH suspending admissions of all patients for the first few months of the pandemic and (2) DSH admitting patients in smaller batches once the suspension of admissions was lifted. Figure 3 illustrates growth in the felony IST waitlist since January 2020.

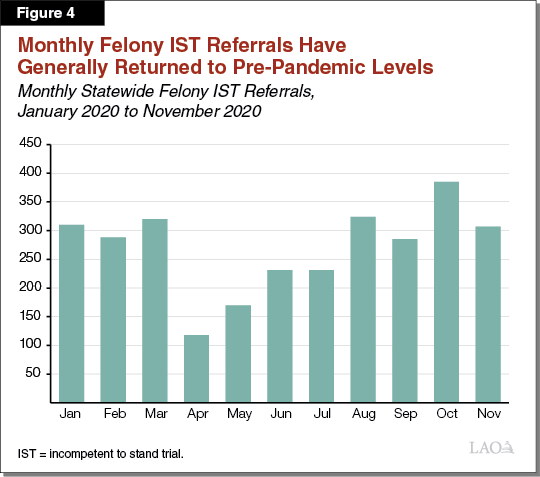

Monthly Felony ISTs Referred to DSH Generally Have Returned to Pre‑Pandemic Levels. In prior years, DSH experienced gradually rising numbers of felony ISTs referred for competency restoration treatment. The average number of felony ISTs referred per month increased by roughly 20 percent between 2015‑16 and 2018‑19. However, in response to the COVID‑19 pandemic, DSH imposed a suspension of all admissions into state hospitals in the initial months of the pandemic. This, combined with reduced capacity in local court systems due to COVID‑19‑restrictions, led to a decline in the number of felony ISTs referrals as shown in figure 4. (From March 2020 to April 2020, referrals declined 63 percent.) DSH continued to experience lower numbers of felony IST referrals until August 2020, when COVID‑19‑related restrictions were lifted. In the months since then, the number of felony IST referrals has returned to roughly pre‑pandemic levels.

Stiavetti v. Ahlin. In 2016, the American Civil Liberties Union filed a lawsuit against DSH alleging that the constitutional rights of felony ISTs were being violated due to DSH failing to place felony ISTs into competency restoration treatment in a timely manner. A California Superior Court ruled that DSH is required to place felony ISTs into competency restoration treatment within 28 days, and gave DSH until October 2020 to comply with the order. DSH appealed the ruling and the effect is on stay pending results of the appeal. If DSH’s appeal is unsuccessful (and DSH is unable to meet the 28 day time frame order by the court), the department potentially could be subject to fines or placed under federal receivership.

Governor’s Proposal

Establish County Felony IST Demonstration Project. This proposal would provide $233.2 million General Fund in 2021‑22, and $136.4 million in 2022‑23 and ongoing, to establish a county felony IST demonstration project known as the Community Care Demonstration Project (CCDP). Under this proposal, DSH would contract with some counties—those choosing to participate in the project at their option—to provide competency restoration treatment. DSH would provide fixed ongoing funding to participating counties for these services. Any funding provided to counties in excess of their treatment costs would be required to be used to increase community behavioral health services. The intent of this requirement is to expand access to behavioral health treatment broadly in order to prevent felony ISTs.

Participating Counties Would Assume Responsibility for All Felony ISTs. In contrast to existing programs where DSH contracts with counties to treat some felony ISTs, under the CCDP, participating counties would assume responsibility—as of July 1, 2021—for treating all felony ISTs in their counties. This would result in an optional realignment of responsibility for treating felony ISTs to counties.

Participating Counties Would Receive Fixed Annual Funding to Treat Felony ISTs. Under the CCDP, DSH would provide $136.4 million General Fund annually on an ongoing basis (transferred in monthly increments) to counties that elect to participate in the CCDP. According to the administration, this amount is based on (1) the cost of care at DSH for a felony IST and (2) an assumption that participating counties would treat an estimated 1,252 felony ISTs annually. The estimated number of felony ISTs is based on the actual number of felony IST referrals from a sample of three undisclosed counties (The administration has stated that it will update this cost estimate at the May Revision based on further information about which counties will participate in the program.) This estimate represents roughly 30 percent of total felony IST referrals statewide. Counties could use this funding to provide competency restoration treatment in the same treatment settings as existing DSH programs (JBCT and CBR programs).

Participating Counties Also Would Receive One‑Time Funds. Under the CCDP, DSH also would provide the following General Fund amounts to participating counties on a one‑time basis: (1) $49.8 million to treat felony ISTs on the existing IST waitlist on July 1, 2021, (2) $35 million to build infrastructure capacity (including securing additional housing and beds across counties and hiring staff), and (3) $11.9 million to treat felony ISTs sent to the current CBR program prior to July 1, 2021. (DSH is requesting a current‑year augmentation to expand capacity at its CBR program, and also expects that the county which operates its existing CBR program will participate in the CCDP. This one‑time funding in 2021‑22 would be provided to treat the additional felony ISTs who entered the CBR program prior July 1, 2021 since treatment of these ISTs would not be built into the county’s fixed annual funding amount under the CCDP.)

DSH Would Reassess Methodology for Ongoing Funding Amount After Three Years. Under the CCDP, DSH would reassess the methodology for determining the ongoing funding amount provided to participating counties after three years. Notably, any adjustments would be based on “natural growth” factors such as overall population changes in participating counties. Adjustments would not be based on changes in the felony IST population, despite the original methodology being based on the number of felony ISTs participating counties are estimated to be responsible for.

Participating Counties Would Be Charged a Premium for Use of State Hospital Beds. Not every felony IST can be treated adequately by counties, as some felony ISTs require a higher level of care that only can be provided in state hospitals. In recognition of this need, DSH would allocate a set number of state hospital bed days for use by participating counties. Counties would pay 150 percent of DSH’s current daily bed rate for these stays. For any state hospital bed days in excess of the set amount, counties would pay an additional premium according to a tiered structure that has yet to be released. DSH intends this pricing structure to act as a disincentive for counties to send felony ISTs to DSH.

Counties Required to Invest Any Remaining Funds Into Community Behavioral Health. There are two ways in which participating counties could have funds left over after treating their felony ISTs: (1) if the actual number of felony ISTs in participating counties is below what DSH estimated or (2) if participating counties are able to reduce the rate—through their own actions—at which individuals are found to be IST in felony cases. If participating counties have available funds left over, they would be required to use them to expand capacity for community behavioral health treatment. The administration’s intent is that this requirement would help reduce the overall rate at which felony ISTs are referred to competency restoration. Specifically, the goal is to increase access to behavioral health treatment (beyond just competency restoration) in order to treat individuals before they commit an offense that could render them IST. Counties would be required to use the available funding to focus on individuals at particular risk of ultimately being found IST.

Proposal Would Require DSH to Collect Some Data and Report to Legislature on Effectiveness of County Strategies. Under the CCDP, participating counties would be required to submit community treatment plans and specified data to DSH annually. This data could include the recidivism rates for felony ISTs restored to competency by participating counties. DSH plans to use this information to assess feasibility for statewide implementation of this project. In addition, under this proposal, DSH would be required to report to the Legislature by February 1, 2025 on the effectiveness of county strategies to treat felony ISTs and reduce the amount of individuals found to be IST.

Assessment

Concept of Realigning Treatment of Felony ISTs to Counties Has Merit. Given that the treatment needs of felony ISTs generally are similar to those of misdemeanor ISTs (with the exception of a subset of felony ISTs who require a higher level of care), counties are already positioned to treat felony ISTs. Counties also already are responsible for mental health treatment for individuals with severe mental illness, such as under the Medi‑Cal program. In addition, the Legislature has approved several DSH programs in recent years that provide for county treatment of felony ISTs, including the JBCT and CBR programs.

In Contrast to Existing DSH Programs, Proposal Attempts to Reduce Rate at Which Individuals Are Found to be IST… In contrast to the existing programs discussed above—in which counties are provided funding to provide competency restoration treatment to felony ISTs on the state’s behalf—this proposal makes an attempt to reduce the rate at which individuals are found to be IST and referred for treatment in the first place. In concept, the added value that this proposal would provide over existing DSH felony IST treatment programs is the potential for counties to use available funds to help reduce felony IST referrals through investments in their community behavioral health systems. Specifically, the proposal intends for counties to treat individuals before the point when they commit an offense that could render them IST. Increasing community behavioral health services to prevent felony IST referrals in the first place could improve overall delivery of county services and mitigate pressures on state hospitals.

...But Is Not Well Structured to Achieve Goals, Leading to Questionable Added Value Over Existing DSH Programs. While the Governor’s proposal has merit in concept, it is not well structured to achieve its stated goal for several reasons.

- Proposal Lacks Strong Incentives for Counties to Participate. While counties cover the costs of felony ISTs on the state hospital waitlist, counties do not pay for their ultimate treatment costs. Consequently, the primary fiscal incentive for counties to take on felony IST treatment would be to avoid the costs incurred while individuals await a state hospital bed. Counties would need to weigh this potential benefit against (1) the added responsibility of treating all felony ISTs and (2) the premium they would have to pay to send select felony ISTs to DSH. Moreover, DSH cannot guarantee these individuals would be admitted to a state hospital in a timely manner. Some of these felony ISTs could still end up on the waitlist, waiting in county jails for transfer to DSH for treatment.

- Whether Counties Would Have Funds Available to Reduce Rate of Felony IST Referrals Is Unclear. Reducing the rate at which individuals are found to be IST in the first place requires addressing individuals’ underlying behavioral health needs prior to the point at which an individual commits an offense that could render them IST. To do this, counties would need to invest in overall behavioral health service activities (that are targeted at individuals especially likely to be found IST), not just competency restoration. The CCDP does not directly fund investments in overall behavioral health, despite this being a priority of the proposal. Moreover, whether counties would have funds available for these investments would be subject to considerable uncertainty.

- Proposal Not Designed to Reduce Felony IST Referrals Statewide. Funding for the CCDP would only affect the assumed small number of participating counties, and whether those counties could reduce the number of individuals found to be IST and referred for treatment is highly uncertain. Given the degree of urgency associated with reducing felony IST referrals statewide, we find that this proposal is unlikely to make a meaningful impact in this regard.

Ongoing Funding Does Not Make Sense for a Demonstration Project. The administration has characterized the CCDP as a demonstration project, intended to help provide insight on the proposed program’s effectiveness and the feasibility for statewide implementation. However, the administration is proposing to fund the CCDP on an ongoing basis prior to the state being able to make these assessments. As a result, providing ongoing funding to the proposal prior to making these assessments is premature.

Overlap With Existing Programs Raises Concerns. As noted earlier, the novel part of the CCDP proposal is the potential for reducing felony IST referrals. Our assessment of this element, however, finds the proposal is unlikely to achieve this benefit. The remainder of the proposal has significant overlap with existing programs for county‑based competency restoration treatment. Moreover, DSH is requesting additional funding in the Governor’s budget to support these existing programs. These include (1) $6.3 million General Fund ongoing to establish additional JBCT programs and (2) $4.5 million in 2021‑22 (increasing to $4.9 million in 2022‑23 and ongoing) to expand the current CBR program to additional counties. Given that DSH already is requesting funding for programs that will also provide competency restoration treatment, creating a new program that will largely serve the same function does not appear justified.

Other Governor’s Budget Proposals May Have More Meaningful Impact in Reducing Felony IST Referrals. The Governor’s budget includes several major behavioral health proposals outside of the DSH budget that relate directly to the provision, or expansion of capacity, of community behavioral health services. These include (1) a major new benefit proposed for Medi‑Cal (California’s state Medicaid program) known as Enhanced Care Management (ECM) that would provide care management services to high‑cost and high‑need beneficiaries (including justice‑involved individuals) and (2) $750 million in the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) to provide grants to counties to acquire or renovate facilities for behavioral health services. Since these proposals directly relate to community behavioral health service delivery, we find that they present an opportunity for DSH to coordinate with other departments to make individuals at particular risk of being declared IST a target population for these proposals.

Recommendations

Reject Proposal. Given that counties already are responsible for treatment of misdemeanor ISTs and for overall mental health treatment for individuals with severe mental illness, we find that, in concept, realigning responsibility for treatment of felony ISTs to counties has merit. For the various reasons discussed above, however, we do not find this budget proposal to be well structured to achieve its goal of reducing the rate at which individuals are found to be IST and referred to competency restoration. Moreover, creating a new program that largely would serve the same function as existing programs does not appear to be justified. We therefore recommend rejecting the proposal.

Consider Redirecting Funding to Existing County Treatment Programs. Should the Legislature wish to increase the state funding for competency restoration treatment for felony ISTs, we recommend considering directing additional funding to existing programs such as JBCT or the CBR program.

Explore Alternative Options for Investment in Community Behavioral Health Treatment Focused on “at‑Risk‑of‑IST” Population. As discussed earlier, there are several major Governor’s budget proposals outside of DSH for behavioral health. These proposals could provide an opportunity for coordination between DSH and other departments on how to include individuals at risk of being found IST as a target population in these other efforts. This could include, for example, working with DHCS to determine how to incorporate these individuals into the new proposed ECM benefit or as a target population in the DHCS‑proposed $750 million grant program for community behavioral health facility acquisition. Finally, some other existing programs outside of DSH offer additional opportunities for interdepartmental coordination. For example, counties currently fund programs called Full Service Partnerships (FSPs), which are funded through the revenues they receive from the Mental Health Services Fund. These partnerships are meant to provide comprehensive services to individuals with severe mental illness (with a particular focus on justice‑involved individuals). DSH could work with counties to try to make individuals at particular risk of being found IST more of a focal point of FSP programs.