LAO Contact

February 23, 2021

Updating Special Education Out-of-Home Care Funding

- Introduction

- Out‑of‑Home Care Funding

- Continuum of Care Reform

- Work Group Assessment

- Work Group Recommendations

- LAO Comments

- Conclusion

Summary

Legislature Established Out‑of‑Home Care Work Group and Required Report. In the Supplemental Report of the 2020‑21 Budget Act, the Legislature tasked our office with convening a work group and providing recommendations for updating the special education Out‑of‑Home Care formula by March 1, 2021. Since 2004‑05, the state has provided these funds to schools to cover costs associated with special education services for foster youth and some children with developmental disabilities who are unable to live with a custodial parent. Due to reforms to phase out long‑term congregate care placements for foster youth, the Out‑of‑Home Care rate structure was effectively rendered obsolete, and funding has been frozen since 2016‑17. This report provides background on the issues, describes the assessment and recommendations of the work group, and includes our office’s comments for the Legislature as it considers updating the formula.

Work Group Recommends Near‑ and Long‑Term Approaches. The work group developed a set of near‑ and long‑term recommendations to update the formula. In the near term, the work group recommends the Legislature replace the formula rates for foster youth with a two‑tiered model—providing one rate for all foster youth and another rate for short‑term congregate care placements. This approach reflects the recent changes to the child welfare system and could be implemented without significant challenges. In the long term, the work group recommends the Legislature explore an Out‑of‑Home Care formula based on the comprehensive assessment—known as the Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths (CANS)—used to assess levels of need for each foster youth. Work group members thought this approach would best encourage interagency collaboration and capture variations in foster youth needs and costs across the state.

Several Steps Before State Could Implement a CANS‑Based Funding Model. Although the work group identified various strengths of a CANS‑based formula, this approach is also likely to face implementation challenges and take many years to implement. Notably, data from the CANS assessment is not yet automated and centralized, and the time line for automation is uncertain. A CANS‑based model could also create new fiscal incentives, especially if education representatives—whose funding levels would be determined by the assessment—were directly involved in the assessment process. This could result in foster youth being identified as having higher levels of need than otherwise. In developing and evaluating a CANS‑based funding model, the Legislature will want to consider the extent to which the model creates fiscal incentives to change behavior.

Introduction

Out‑of‑Home Care Funding Formula Created to Address Variation in Special Education Costs for Certain Students. Since 2004‑05, the state has provided some special education funding through the Out‑of‑Home Care program to schools. This funding was intended to cover costs associated with providing educational services to foster youth and some children with developmental disabilities who are unable to live with a custodial parent for a variety of reasons. Children in these out‑of‑home placements qualify for special education at higher rates than other children, often requiring additional education services and supports. Children with the most intensive and likely costly needs are served by congregate care facilities, which are unevenly distributed throughout the state. The Out‑of‑Home Care funding formula accounts for the variation in these placements across the state.

Special Education Out‑of‑Home Care Funding Has Been Frozen Since 2016‑17. Recent changes to the child welfare system, including a reduced reliance on long‑term congregate care, created a need to revise the Out‑of‑Home Care formula for foster youth. In anticipation of such a change, the state has kept Out‑of‑Home Care funding allocations for foster youth at 2016‑17 levels in recent years.

Legislature Established Out‑of‑Home Care Work Group and Required Report. The Legislature tasked our office with convening a work group and providing recommendations for updating the Out‑of‑Home Care formula by March 1, 2021. As required by the Supplemental Report of the 2020‑21 Budget Act, the group included representatives from fiscal and policy committees of the Legislature, the Department of Finance, the California Department of Education (CDE), the California Department of Social Services (DSS), and the California Department of Developmental Services (DDS). The group met seven times over the course of fall 2020. This report provides background on Out‑of‑Home Care funding and Continuum of Care Reform (CCR), the assessment and recommendations of the work group, and our office’s comments for the Legislature as it considers implementing the recommendations.

Out‑of‑Home Care Funding

Out‑of‑Home Care Includes Placements for Foster Youth. California’s child welfare system serves to protect the state’s children from abuse and neglect, often by providing temporary out‑of‑home placements for children who cannot safely remain in their home. Most of these placements are with resource families—noncustodial relatives and nonrelative foster families approved to provide care to foster youth. Foster youth also can be placed in congregate care, which includes group homes and Short‑Term Residential Therapeutic Programs (STRTPs). Congregate care is considered the most restrictive and least family‑like setting. These settings provide 24‑hour care and supervision to foster youth with the highest levels of needs, including those with significant emotional or behavioral challenges. (See the box below for more detail on the terms we use in this report to refer to types of child placements.) As of October 1, 2020, the state had 60,045 foster youth in out‑of‑home placements. Of this total, 40,831 youth were placed with a resource family; 2,295 youth were placed in a congregate care setting; and the remaining were placed in other settings, such as transitional housing for older foster youth preparing for independent living. DSS oversees the state’s child welfare system, but most services are provided by county child welfare departments.

Terms Related to Child Placement

Out‑of‑Home Placement. Placements for children who are unable to live with a custodial parent for a variety of reasons. For the purposes of this report, out‑of‑home placements include foster youth placed with a resource family or in a congregate care facility, as well as children with developmental disabilities placed in congregate care.

Congregate Care. A placement setting licensed by the state to provide 24‑hour care and supervision to children. Congregate settings include group homes, Short‑Term Residential Therapeutic Programs (STRTPs), community care facilities, intermediate care facilities, and skilled nursing facilities.

STRTPs. As one type of congregate care, STRTPs are intended to provide exclusively short‑term, intensive treatment and other services facilitating youth’s transition to a family setting as quickly and successfully as possible.

Resource Family. Noncustodial relatives and nonrelative foster families approved by the county child welfare agency to provide care to foster youth.

Children With Developmental Disabilities Can Also Receive Out‑of‑Home Care. Separate from foster youth, some children with significant intellectual or developmental disabilities are also placed in out‑of‑home care, specifically congregate care. These placements can occur if a child requires substantially more care than their family can provide in the home. Such children often require significant medical support and may have severe or profound disabilities. Out‑of‑home placements provide 24‑hour care for these children and include community care facilities, intermediate care facilities, and skilled nursing facilities. DDS is responsible for designing and coordinating services for individuals with developmental disabilities. As of April 1, 2020, the state had 1,564 children with developmental disabilities placed in congregate care settings.

Out‑of‑Home Placements Are More Likely to Receive Special Education. Special education is instruction designed to meet the unique needs of each student identified with a disability that affects their ability to learn. Nearly all children with developmental disabilities in out‑of‑home care qualify for special education. Among foster youth, the estimated share of students with disabilities (30.4 percent) was more than twice that of all other children in California (12.7 percent) in 2018‑19. The traumatic childhood experiences that cause a youth to come in contact with the child welfare system may also result in behavioral and social‑emotional challenges that qualify them for special education services. Although specific data are not available, anecdotal evidence suggests that special education rates are higher for foster youth placed in congregate care than those placed with resource families.

State Primarily Funds Special Education Based on Overall Student Attendance. Most state special education funding is allocated through a base rate formula commonly called “AB 602” (after its enacting legislation in 1997). The formula distributes funding based on total student attendance rather than a more direct measure of special education costs, such as the number of students qualifying for special education. This approach assumes the underlying identification rates and costs for special education are comparable across the state. The state allocates most special education funding to Special Education Local Plan Areas (SELPAs), which are regional consortia formed to coordinate special education services and funding. State law requires school districts, charter schools, and county offices of education to participate in a SELPA, with large districts typically acting as their own SELPA. In 2020‑21, the state provided $3.2 billion to SELPAs in AB 602 base funding.

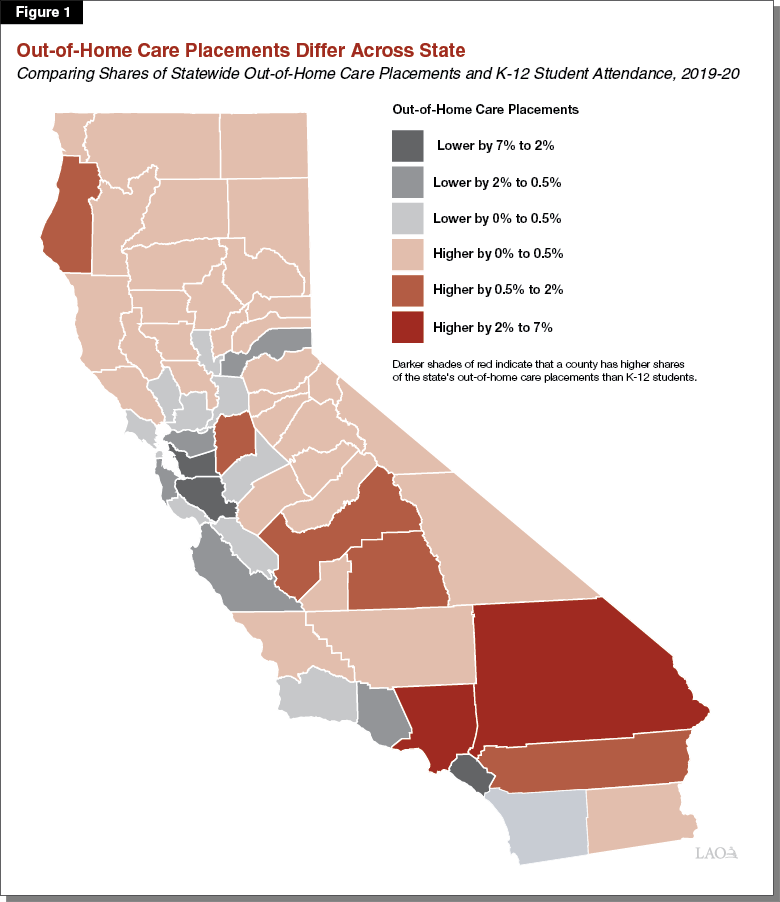

Out‑of‑Home Placements Are Not Evenly Distributed Throughout the State. Figure 1 shows how distributions of out‑of‑home placements compare with that of all students across the state. Although many counties have somewhat proportional shares of out‑of‑home placements relative to the number of students they serve, a small number of counties have larger differences between the two populations. Los Angeles and San Bernardino Counties have disproportionately higher shares of out‑of‑home care placements, while San Diego and Orange Counties have disproportionately lower shares. Variations are also seen at the SELPA level. For instance, we estimate one SELPA served an average of 300 foster youth in congregate care in 2019‑20, while 55 SELPAs serve none as they have no such facilities within their boundaries.

Education Costs for Out‑of‑Home Placements Are Also Not Evenly Distributed. When a child is placed into congregate care by a noneducation agency, such as the county child welfare department, the responsibility to provide and fund education for the child generally falls on the local school district. (One minor exception is when a child is placed in a facility within another school district’s catchment area but continues to attend their original school of origin.) Because congregate care facilities are not evenly distributed across the state, the cost of educating children living in congregate care also unevenly falls on school districts where these facilities are located. Furthermore, education costs for these children can be costly given the significant needs these children have exhibited to warrant higher levels of care.

State Provides Special Education Funding for Out‑of‑Home Placements. Recognizing that the special education base formula could not account for the uneven distribution and costs for out‑of‑home placements, the state implemented the Out‑of‑Home Care program in 2004‑05. This program provides additional special education funding to each SELPA based on three components: (1) counts of foster youth placed with foster families, (2) bed capacity of group homes, and (3) counts of children with developmental disabilities placed in out‑of‑home care. To determine the level of funding for each SELPA, the formula uses a child’s placement as a proxy for the cost of providing educational services. As shown in Figure 2, the rates are based on the severity level of group homes assigned by DSS ranging from level 1 to level 14, with level 14 group homes serving children with the most severe and costly needs. The formula sets rates for other out‑of‑home placements based on corresponding group home severity levels. For example, the rates for students in foster family placements are similar to those of lower level group homes, while the rate for skilled nursing facilities corresponds to the highest level group home. Out‑of‑Home Care funding, however, is not required to be spent on children in out‑of‑home care. Funds can be spent on any special education activity. The 2020‑21 budget provided $142 million for the Out‑of‑Home Care program. The state does not collect data on the cost of providing special education services for students in out‑of‑home placements. Special education administrators report, however, that the cost of providing such services is often greater than the amount of funding provided by the state.

Figure 2

Out‑of‑Home Care Rates Are Based on

Group Home Classifications

2019‑20

|

Rate |

Group Home |

Other Out‑of‑Home |

|

$644 |

Level 1 |

Foster Family Home |

|

785 |

Level 2 |

|

|

1,845 |

Level 3 |

|

|

2,121 |

Level 4 |

|

|

2,399 |

Level 5 |

|

|

2,675 |

Level 6 |

|

|

2,953 |

Level 7 |

|

|

3,228 |

Level 8 |

Community Care Facility |

|

7,012 |

Level 9 |

|

|

7,566 |

Level 10 |

|

|

12,175 |

Level 11 |

Intermediate Care Facility |

|

17,341 |

Level 12 |

|

|

18,448 |

Level 13 |

|

|

25,828 |

Level 14 |

Skilled Nursing Facility |

Continuum of Care Reform

CCR Aims to Eliminate Group Homes and Promote Home‑Based Family Placements. Beginning in 2012, the Legislature passed a series of legislation implementing CCR. This legislative package makes fundamental changes to the way the state cares for youth in the child welfare system. CCR aims to achieve a number of complementary goals, including: (1) ending long‑term congregate care placements, (2) increasing reliance on resource family placements, (3) improving access to supportive services regardless of a child’s foster care placement, and (4) utilizing universal child and family assessments to improve placement and services.

Short‑Term Therapeutic Programs Replace Group Homes. Compared with resource family placements, long‑term group home placements are associated with elevated rates of reentry into foster care, lower educational achievement, and higher rates of involvement in the juvenile justice system. Furthermore, congregate care placements are costly compared to placements with resource families. Given these concerns about group homes, a key goal of CCR is to end group homes as a placement option for foster youth. Under CCR, more foster youth with higher needs are now placed with resource families with additional services, whereas previously they would have been placed in a higher level group home. For youth who cannot safely and stably be placed with resource families, child welfare agencies can place the child in STRTPs. As previously discussed, these placements provide a similar level of supervision as group homes, but with expanded services and supports. STRTPs are intended to provide exclusively short‑term, intensive treatment and other services facilitating youth’s transition to placement with a resource family as quickly and successfully as possible. The deadline for group homes to convert to STRTPs was the end of December 2020.

Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths (CANS) Tool Used to Inform Decisions. To increase child and family involvement in decisions relating to foster youth’s care, CCR mandates the use of child and family “teaming” in the case planning and service delivery process. The child and family team (CFT) may include, as deemed appropriate by the social worker, the affected child, custodial and noncustodial parents, extended family members, the county caseworker, representatives from the child’s out‑of‑home placement, the child’s mental health clinician, and other persons with a connection to the child. The CFT is required to meet at least once every six months to discuss and agree on the child’s placement and service plan. CCR requires foster youth to receive a comprehensive assessment upon entering foster care to improve placement decisions and ensure access to necessary supportive services. In late 2017, DSS chose the CANS tool as the state’s functional assessment tool to be used within the CFT process. The CANS assessment intends to help the CFT organize information, communicate clearly, and reach consensus on the child’s placement and service plan. The CANS assessment uses a rating scale to indicate levels of need and service in various areas of a child’s life, including school, work, home, and social relationships. The tool is currently used only to inform the placement and care decisions of the CFT.

Implementation of CANS Continues. In 2019, counties began using CANS assessments as part of the CFT process. As of fall 2020, counties are using slightly different versions of the CANS assessments and are in different stages of automating the assessment process. For instance, in May 2020, nearly 18,000 CANS assessments had been completed in an automated system, but our understanding is that more assessments had been completed in paper form. Exactly how many assessments have been completed in total, however, is unclear.

Changes Due to CCR Affect Out‑of‑Home Care Formula. Because CCR eliminated group homes, the Out‑of‑Home Care rate structure based on group home severity level was effectively rendered obsolete. In recent years, the state has continued to provide Out‑of‑Home Care funding, but counts of foster youth and bed capacity for group homes have been frozen at 2016‑17 levels for each SELPA. In other words, for the past several years, Out‑of‑Home Care funding has not accounted for changes in foster youth counts in each SELPA, the placement of more foster youth with resource families, or the replacement of group homes with STRTPs. As more time passes, the disconnect between Out‑of‑Home Care funding and where foster youth and STRTPs are located continues to grow larger. For instance, although 2,382 foster youth were placed in congregate care as of July 1, 2020, the Out‑of‑Home Care formula provides funding for 7,103 group home beds (based on 2016‑17 levels). In contrast to foster youth, the counts for children with developmental disabilities in out‑of‑home care continues to be updated in the Out‑of‑Home Care program.

Work Group Assessment

Assessment Hones in on a Handful of Key Considerations. This section highlights the key priorities and considerations that emerged from the work group discussions on updating the Out‑of‑Home Care formula. This section is not intended as a comprehensive account of everything discussed in the work group, nor is it intended to be an exhaustive list. Instead, this section reflects our view of the most significant elements of the work group’s deliberations.

Work Group Developed Six Guiding Principles for A New Formula. As seen in Figure 3, the work group developed six key principles to use in evaluating options for a new Out‑of‑Home Care formula. These principles were developed after a review of the historical context of special education funding, meetings with various stakeholders, and discussion among work group members. After deciding on the guiding principles, the work group considered various options for updating Out‑of‑Home Care funding and used these principles to evaluate each option.

Figure 3

Six Guiding Principles for Updating the Out‑of‑Home Care Formula

|

|

|

|

|

|

Variation in Costs Best Addressed Through Separate Program. One option the work group considered was eliminating the Out‑of‑Home Care program and shifting funding into the special education base formula (slightly increasing per‑student rates for all SELPAs). This approach addresses several of the work group’s guiding principles, including making special education funding simpler and easier to understand. The work group ultimately concluded, however, that keeping Out‑of‑Home Care funding as a separate program would better account for SELPA‑level differences in foster youth needs and costs over time. The work group then considered other options that would allocate funding based on different proxies for the needs and costs of foster youth with disabilities.

CANS‑Based Model May Encourage Interagency Collaboration and Provide a Reasonable Proxy for Level of Need. The work group also discussed the possibility of using the CANS assessment as the basis of a new model. The CANS assessment includes questions regarding behavior, achievement, and attendance in school, as well as the level of support provided by the school. This information could be used to capture variation in the levels of need for foster youth and determine funding for SELPAs according to these needs. An Out‑of‑Home Care formula based on the CANS assessment also could increase interagency collaboration by encouraging education representatives to be involved in the CFT process, CANS assessment, and decision‑making concerning foster youth. Currently, teachers or other education representatives are not required to be involved in answering the education‑related questions on the CANS assessment or participate in the CFT. As explained in the box below, interagency collaboration was one of several challenges broadly affecting education for foster youth that the work group discussed.

Other Issues Related to Education for Foster Youth

Work Group Process Revealed Other Educational Challenges for Foster Youth. Through conversations with various stakeholders, the work group discussed other issues related to foster youth and education. Although these issues fell beyond the group’s charge to update the Out‑of‑Home Care formula, we detail two issues below for further legislative consideration.

Foster Youth Would Benefit From More Interagency Collaboration. During our meetings this fall, work group members involved in K‑12 education attributed the obsolete Out‑of‑Home Care funding formula to an initial lack of collaboration between the education and foster care systems. Primarily, education stakeholders attributed the disconnect between special education funding for foster youth and the state’s foster care system to a lack of participation of education stakeholders in the development of Continuum of Care Reform. The work group found interagency collaboration to be highly important in improving foster youth outcomes and sought to encourage such collaboration through its work. Members expressed interest in encouraging a stronger role for education on the child and family team to help ensure that educational issues are taken into consideration during placement decisions. Members also expressed interest in examining and streamlining potentially duplicative processes related to child welfare and special education to relieve demands on families.

High Foster Youth Mobility Creates Challenges Qualifying for Special Education. The work group also discussed concerns that frequent placement changes prevent some foster youth from accessing special education. Although federal law under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act establishes clear time lines for evaluating eligibility for special education services, a foster youth may change placements and be moved to another school district before they are able to complete an evaluation and receive an individualized education program (IEP) specifying the supports and services the school district will provide. The youth would then need to restart the process at the new district to be evaluated for special education. Stakeholders we spoke to indicated that many foster youth without an IEP—especially those placed in a Short‑Term Residential Therapeutic Program—would likely benefit from special education given their high level of social‑emotional needs, but these youth may not have completed the process to qualify for special education due to frequent changes in placement and schooling. Additional delays may occur when the individual legally responsible for making decisions regarding the child’s education is difficult to reach or unfamiliar with the education system.

A CANS‑Based Model Is Not Currently Feasible. Despite the potential strengths of a CANS‑based model, the CANS assessment is still being implemented and standardized across the state. As previously mentioned, counties are in various stages of incorporating the CANS assessment into the CFT process and being able to enter the CANS assessments into an automated system. A CANS‑based model would require reliable and easily updated data, which is not currently feasible without every county uploading CANS data into a centralized statewide data system. The state currently has no specific time line for when the CANS assessment would be fully automated, although DSS shared with the work group a strong commitment to reach full automation within the next several years. The work group also discussed whether the education‑related questions currently included in the CANS assessment are sufficient to evaluate a child’s educational needs or if the assessment should be modified to include additional questions specific to education.

Funding Based on Foster Youth Counts Would Address Some Variation in Costs. The work group also considered a model that would provide Out‑of‑Home Care funding to SELPAs based on one flat rate per foster youth. This model would (1) account for differences in foster youth enrollment by SELPAs, (2) be easy to understand, (3) use reliable and easily updated data, and (4) avoid any inappropriate fiscal incentives. In contrast to the CANS‑based approach and its longer implementation time frame, a new flat‑rate model could be implemented in the near term without requiring additional data or major implementation challenges. Although this model accounts for differences in foster youth enrollment, it does not account for variations in the needs of foster youth across SELPAs. The flat‑rate model also does not include any component that would encourage interagency collaboration.

Funding Based on Foster Youth Counts and STRTP Placements Would Provide More Funding for SELPAs With Higher Costs. In addition to a model based on a flat rate to fund foster youth, the work group considered a “two‑tiered” alternative that set one funding rate for foster youth and a separate rate based on the number of STRTP placements. Similar to the current Out‑of‑Home Care formula, this model captures some degree of variation in needs and costs by using the type of foster youth placement as a proxy for education cost. Because state law restricts use of STRTPs to youth that cannot safely and stably be placed with resource families, children in these placements tend to have significant emotional and behavioral challenges that require more costly educational services. During stakeholder meetings with the work group, both SELPA administrators and STRTP providers mentioned many foster youth placed in STRTPs are qualified to receive special education or would greatly benefit from special education.

Allocating Funding to SELPAs Based on STRTP Location Appropriate in Most Instances. One issue the work group discussed was the case in which a foster youth is placed in an out‑of‑county STRTP but continues to receive education from the school of origin in another SELPA. In this case, funding would be allocated to the SELPA where the STRTP is located, not the SELPA providing educational services. The work group ultimately decided not to make modifications to address this issue. SELPA administrators we spoke to indicated that this scenario occurs rarely and, when it does occur, SELPAs or school districts can make arrangements to claim back costs for providing education.

No Concerns With Funding for Children With Developmental Disabilities. The work group also reviewed the funding for children with developmental disabilities placed in out‑of‑home care. In contrast to the foster youth portion of the formula, counts and funding for children with developmental disabilities continue to be updated for each SELPA. As previously mentioned, the school district where the congregate care facility is located is responsible for providing education. The work group found that the current formula appropriately allocates funding to the SELPA of the school district responsible for providing education for children in these settings. Stakeholders expressed no concerns with how funding was allocated under this component of the formula. The work group decided the rates for children with developmental disabilities in out‑of‑home care should remain as they are under the current formula.

Work Group Recommendations

In the Near Term, Update Formula With One Rate for All Foster Youth and One for STRTP Placements. The work group developed a set of near‑ and long‑term recommendations. In the near term, the work group recommends the Legislature replace the Out‑of‑Home Care rates for foster youth with a two‑tiered model providing one rate for all foster youth and another rate for STRTP placements. (Foster youth placed in STRTPs would generate funding from both rates.) The work group thought this two‑tiered model aligned with the approach of the current Out‑of‑Home Care formula, was easy to understand, could be implemented and updated without significant challenges, and accounted for some variation in cost. The work group also developed recommendations for some specific components of the formula. For example, the work group recommends expanding the definition for foster youth funded under the updated Out‑of‑Home Care formula to align with other definitions used for education funding. The recommendations are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Specific Work Group Recommendations for Near‑Term Approach

|

Formula Component |

Current Funding Formula |

Near‑Term Approach Recommendation |

Rationale |

|

Foster Youth Definition |

Foster Families and Group Homes. Funds only foster youth placed with foster families or group homes. |

Expanded Definition. Expand definition to include foster youth who (1) are placed with a noncustodial parent or relative (2) are voluntarily placed in out‑of‑home care, and (3) remain in the family home while receiving voluntary family services. |

Aligns with other foster youth definitions used in education funding. Also includes voluntary placements since these children are likely to have a disability diagnosis. |

|

Foster Youth Count |

Census Day Count. Captures foster youth enrollment on one day in the school year. |

Cumulative Enrollment. Use cumulative enrollment instead of a point‑in‑time count. Cumulative enrollment captures enrollment of foster youth throughout the school year. |

Captures frequent changes in schooling of these students and provides for any associated one‑time upfront costs. |

|

STRTP Count |

Bed Count. Funds group homes based on number of beds. |

Average Daily Population. Use STRTP average daily population rather than bed count. The average daily population represents an average occupancy rate over the year. |

Provides a more precise and appropriate measure of the number of foster youth served in STRTPs throughout a year. |

|

Charter SELPA Funding |

Not Funded. Excludes charter‑only SELPAs. |

Expanded Funding. Include charter‑only SELPAs. |

Appropriately funds charter schools for serving foster youth. |

|

STRTP = Short‑Term Residential Therapeutic Program and SELPA = Special Education Local Plan Area. |

|||

In the Future, Explore a CANS‑Based Formula as Proxy for Educational Need. In the long term, the work group recommends the Legislature explore a CANS‑based Out‑of‑Home Care formula. Work group members thought using inputs from the CANS assessment to allocate funding would best encourage interagency collaboration and capture variations in foster youth needs and costs across the state. Work group members also wanted the current CANS assessment to be evaluated from an education perspective and, if necessary, further modified to appropriately serve as the basis of an education funding formula. Many members noted how exploring a CANS‑based formula would be consistent with recent, larger state policy shifts to encourage interagency collaboration and better alignment across different areas of state government.

LAO Comments

Comments Provide Additional Considerations for the Legislature. In this section, we provide comments on the two models recommended by the work group, offer options for issues the work group was not able to address, and discuss issues for the Legislature to consider for implementing a CANS‑based formula.

Near‑Term Approach Conceptually Aligns With Current Formula. In our discussions with special education stakeholders, few had concerns with the Out‑of‑Home Care formula prior to the changes under CCR that made the formula obsolete. Of the options considered by the work group, the two‑tiered model most closely resembles the current formula, with rates updated to reflect placement options now available under CCR. Given the lack of concern with the previous formula and the benefits of accounting for variation in costs across the state, we consider the two‑tiered model to be a reasonable update of the Out‑of‑Home Care formula. One notable difference between the current model and the two‑tiered model is how congregate care placements are funded. Whereas the current model provides funding based on bed capacity, the work group recommends using the average daily population of foster youth in STRTPs. During work group discussions, a concern was raised that differentiating funding based on placement could create fiscal incentives for children to be placed in more restrictive settings. Placement decisions, however, are made by county child welfare departments and the CFT, not the SELPAs receiving Out‑of‑Home Care funding. Assuming placement decisions for foster youth continue to be made outside of education, we do not have concerns that the formula would encourage more restrictive placements.

Legislature Could Use DSS Foster Placement Rates as Basis for Setting Near‑Term Out‑of‑Home Care Rates. One key detail not resolved in the work group was the specific per‑student rates to set for the two‑tiered model. Because the state does not require SELPAs to track student‑level expenditures, the cost of providing special education services to foster youth is unknown. Given the lack of education expenditure data, the Legislature could consider using the DSS foster care payment rate structure as the basis for determining the Out‑of‑Home Care funding rates for STRTP placements and foster youth. This approach assumes the difference in rates DSS pays for STRTP placements relative to other foster care placements is similar to the difference in education costs based on placement. Starting July 2020, the monthly foster care rate for STRTP placements is $14,035 per child, while the monthly foster care rate for resource family placements ranges between $1,000 and $6,388, depending on a youth’s level of support needs. Assuming total Out‑of‑Home Care funding remains the same in 2021‑22, we estimate the state could provide an annual rate of $14,035 for STRTP placements and $1,450 for foster youth. If the Legislature is interested in setting rates more directly aligned with education costs, it could fund a study or require CDE to conduct a survey to assess whether the DSS rates are reasonable proxies for special education costs.

Consider Phasing in Formula Over Several Years. Because some SELPAs will see decreases in funding under the new formula, the Legislature may want to consider phasing in the new formula over time to ensure a smooth transition. For example, the state could slowly ramp up the transition in the first year by providing 25 percent of funding under the new formula and 75 percent under the old formula, then in the second year increase the share of funding from the new formula to 75 percent. Under this approach, the state could phase in implementation over a three‑year period without providing any additional funding.

Several Steps Before State Could Implement a CANS‑Based Funding Model. Although the work group identified various strengths of a CANS‑based formula, this approach is also likely to face implementation challenges and take many years to implement. Notably, the standardization and automation of CANS data has an uncertain time line. Furthermore, centralized, automated CANS data is only a prerequisite to implementing a CANS‑based model—the underlying formulas would still need to be developed. In addition to having a centralized and automated system, implementing the work group recommendations would require evaluating whether the current CANS assessment should be modified to better capture a child’s educational needs. This process likely would require stakeholder engagement and feedback prior to taking specific action to modify the assessment. If the Legislature is interested in enacting changes to improve interagency collaboration at the county level, the state also would need to (1) develop additional policies and guidance related to the role of education agencies in the CFT and CANS assessment and (2) align the CFT process with the assessment process for receiving special education services.

Consider Fiscal Incentives Created by a CANS‑Based Formula. In developing and evaluating a CANS‑based funding model, the Legislature will want to consider the extent to which the model creates fiscal incentives to change behavior. For instance, if education representatives were to become required participants of the CFT and CANS assessment process, they would have a role in decisions that directly affect how much funding they receive for foster youth. This could result in foster youth being identified as having higher levels of need than otherwise. When these concerns were discussed in the work group, members believed the CFT to be a consensus‑driven process that would prevent unilateral decision‑making. Members also mentioned that identifying a child as having a higher level of need also creates expectations to provide higher levels of services, which should counteract any adverse fiscal incentives.

Consider Setting Specific Milestones for Process of Exploring a CANS‑Based Approach. If the Legislature is interested in exploring a CANS‑based Out‑of‑Home Care formula in the future, we recommend it lay out specific milestones for this process. Prior to developing a formula, however, the Legislature would want to determine when CANS implementation has progressed sufficiently to begin actively exploring a new model. The work group discussed two options for identifying this initial milestone. Under the first option, the Legislature could require DSS to provide more detailed updates on the status of CANS standardization and automation for the purposes of modifying the Out‑of‑Home Care formula. (Existing supplemental reporting language already requires DSS to provide quarterly updates on CANS.) Alternatively, DSS leadership could monitor CANS implementation as part of their ongoing interagency work to coordinate timely care for foster youth and report to the Legislature when they believe a CANS‑based model can be explored. We believe either of these options would be reasonable approaches to take. Upon reaching this initial milestone, the Legislature could then convene a new Out‑of‑Home Care work group, including county welfare department and SELPA representatives, to (1) evaluate and potentially modify the CANS assessment for education purposes, (2) determine the appropriate role for education in CFT to improve outcomes for children placed out of home, and (3) develop a new Out‑of‑Home Care model using CANS assessment data that aligns with guiding principles set forth by the work group.

Conclusion

The Out‑of‑Home Care formula is outdated and no longer reflects where foster youth are located or the state’s current child welfare system. Throughout fall 2020, the Out‑of‑Home Care work group met with key stakeholders and leveraged the expertise across members to ultimately recommend a two‑tiered model to update the current formula for the near term. The two‑tiered model includes one rate to fund foster youth and another rate for higher cost STRTP placements. This approach captures some variation in education costs for foster youth with disabilities, while being easy to understand and feasible to update. In the long term, the work group recommended the Legislature explore a CANS‑based formula, after the CANS assessment is fully implemented. A CANS‑based model would incentivize interagency collaboration and better capture variations in foster youth needs and costs. However, as we note in this report, a CANS‑based model may also encounter implementation challenges and introduce new fiscal incentives, which warrant further consideration.