March 5, 2021

The 2021-22 Budget

University Capital Outlay

In this post, we focus on university capital outlay projects. We first provide background on university capital financing and project review. We then review capital outlay proposals for the California State University (CSU) and the University of California (UC). Next, we raise some concerns with the previously authorized UC Merced medical school project and make an associated recommendation. We end the post by offering several other recommendations intended to strengthen legislative oversight of university projects.

Background

New Financing System Put in Place Several Years Ago. Whereas the universities fund their nonacademic facilities (such as their dormitories and bookstores) using nonstate funds, the state historically has funded the universities’ academic facilities (such as their classrooms and laboratories). To finance these academic facilities, the state traditionally sold bonds and directly paid the associated debt service from the General Fund. Beginning in 2013‑14 for UC and 2014‑15 for CSU, the state altered this arrangement by making university bonds, rather than state bonds, the main source of financing for academic facility projects. Under this approach, the universities finance their projects using their main General Fund support appropriations. To prevent capital financing from overwhelming the universities’ operating budgets, state law limits General Fund spending on debt service and pay‑as‑you‑go projects. Specifically, CSU’s limit is 12 percent of its annual General Fund support appropriation, whereas UC’s limit is 15 percent. (In addition to state funds, the universities, particularly UC, commonly receive private donations to support the construction of certain academic facilities. The universities, particularly CSU, also encourage campuses to provide a small campus match from their reserve funds to support their academic facility projects.)

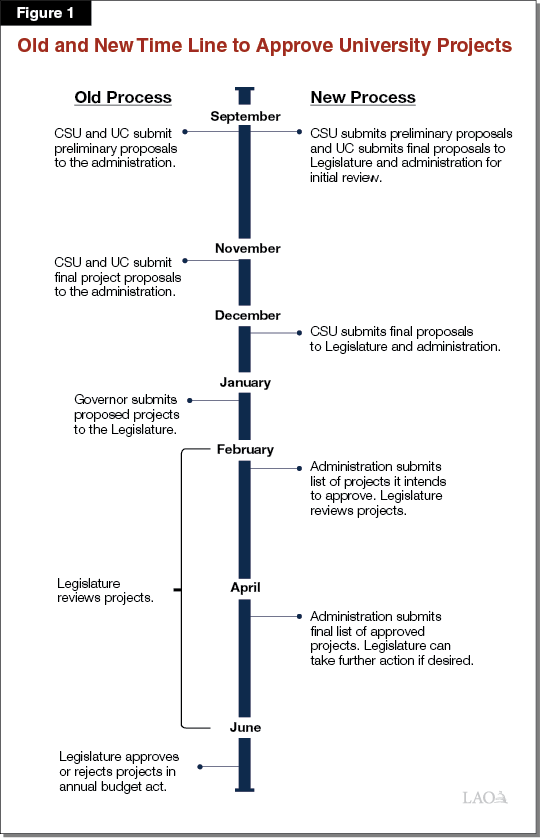

Review Process Designed to Give Legislature Opportunity to Assess Proposals. At the same time the state changed how it funded university academic facilities, it also changed the process it used for approving projects. As Figure 1 on the next page shows, the former approval process was closely connected to the annual budget process. The new process commences at about the same time (in the fall), but then the time line veers somewhat from the budget process. In the fall, CSU and UC are required to submit “the same level of detail” as a capital outlay budget change proposal, or COBCP. (A COBCP contains information about a project’s scope, cost, and schedule.) The administration, in turn, is required to submit to the Legislature a letter by February 1 that identifies the projects it preliminarily approves for each segment. State law requires the administration to provide a final approval letter to the Legislature no sooner than April 1. The period between February and April is intended to give the Legislature a minimum of a couple of months to review projects and signal to the administration its consent or concerns.

Annual February Report Intended to Give Project Updates to the Legislature. State law requires CSU and UC to submit an annual capital outlay progress report by February 1 to the Legislature and administration. This report must include information about all university projects supported by state General Fund, either through university bonds or on a pay‑as‑you‑go basis. The report must provide detail on the scope, cost, and current status of each project.

CSU Proposals

Governor Preliminarily Approves Two CSU Proposals for 2021‑22. On November 30, 2020, CSU submitted its final 2021‑22 capital outlay request, which consisted of two proposals. (CSU’s preliminary request submitted in September 2020 had included 17 proposals.) On February 1, 2021, the Department of Finance (DOF) submitted a letter to the Legislature providing preliminary approval of both proposals. As Figure 2 shows, these proposals have a total cost of $299 million, consisting of $284 million from university bonds and $15 million from campus reserves. The associated annual debt service is estimated to be between $16 million and $19 million. CSU anticipates it would be able to cover this cost within its existing budget for debt service because of lower‑than‑expected interest rates and savings in certain previously approved projects. It estimates its total debt service and pay‑as‑you‑go spending on academic facility projects would be $197 million in 2021‑22, equating to about 5 percent of its General Fund support appropriation.

Figure 2

Governor Preliminarily Approves Two CSU Proposals

2021‑22 (In Thousands)

|

Campus |

Project |

Phases |

State Cost |

Total Costa |

|

Systemwide |

Infrastructure improvements |

Various |

$195,000 |

$200,000 |

|

Chico |

Butte Hall replacement |

P,W,C |

89,012 |

98,663 |

|

Totals |

$284,012b |

$298,663 |

||

|

aCampus reserves are often used for facility projects. bThe associated annual debt service costs are estimated at $16 million to $19 million. P = preliminary plans; W = working drawings; and C = construction. |

||||

First Proposal Would Support Systemwide Infrastructure Improvements. This proposal would authorize CSU to undertake $200 million in infrastructure projects across the 23 campuses. The projects would address building systems deficiencies, energy efficiency, and code compliance, among other issues. CSU would select the projects from a list totaling $1.2 billion in infrastructure improvements that it has submitted to the administration and Legislature for review. (Some projects on this list also appear on a separate list of deferred maintenance projects for which CSU has requested one‑time General Fund in 2021‑22. We cover the deferred maintenance request in our report, The 2021‑22 Budget: Analysis of the Major University Proposals.) The CSU Chancellor’s Office indicates that being able to select projects from among this list provides flexibility to respond to changes in campus priorities, as developments arise between the time campuses initially submit their project lists for state approval and when the funds become available. Under the Governor’s proposal, the Legislature would receive information on the specific projects selected when CSU submits its annual capital outlay progress report due February 1, 2022.

Second Proposal Would Modify a Previously Approved Project at Chico. In 2019‑20, the state authorized the renovation of Butte Hall at the Chico campus at a total cost of $90 million. Since then, the campus has discovered additional hazardous waste remediation needs that would bring the cost of renovation to $106 million. Rather than renovating the building, the 2021‑22 proposal would instead replace the building at a total cost of $99 million.

No Major Concerns With Two Proposals. Though we do not have major concerns with either CSU proposal, we believe the Legislature could provide more meaningful oversight if it had a list of the specific infrastructure improvement projects CSU plans to undertake in 2021‑22. We recommend the Legislature direct CSU to provide this list in the spring, along with an explanation regarding the criteria it used to prioritize among projects.

UC Proposals

Governor Has Not Yet Submitted Preliminary Approval List of UC Projects. Though statute requires the administration to submit its preliminary approval list for UC by February 1, the Legislature had not yet received that list at the time of this writing. According to the administration, it could not make the February 1 submittal deadline because it was awaiting certain information from UC. Specifically, the 2020‑21 budget package included a new ongoing requirement that UC only use service unit employees for maintenance work on facilities supported through the new capital outlay process. UC must certify compliance with this requirement each year before DOF may approve UC projects. According to DOF, UC is still developing a process to use to demonstrate its compliance.

UC Is Requesting Approval of One Project in 2021‑22. In September 2020, UC submitted one project for state approval totaling $117 million in new university bond authority. The project would construct a replacement building for Evans Hall on the Berkeley campus. Evans Hall has a relatively poor seismic rating (Level VI, with Level VII being the poorest rating), and the campus has determined constructing a replacement building would be a more cost‑effective approach for making seismic upgrades than renovating the existing building. The replacement building would contain around half of the assignable square feet of Evans Hall, with the reduction in space primarily due to fewer faculty offices, research laboratories, and library/study spaces. According to UC, the campus plans to accommodate any displaced functions by improving utilization of other existing campus spaces. Assuming the administration’s preliminary letter does not make any changes to the September proposal, we do not take issue with this project.

UC Merced Medical Education Project

UC Received Authority for Merced Project in 2019‑20. The 2019‑20 Budget Act authorized UC to pursue medical school projects at the Riverside campus and at or near the Merced campus. Provisional budget language stated intent that the projects be financed by state‑supported university bonds. In September 2019, UC submitted to the state a proposal for the Riverside project, which totaled $100 million in associated bond authority. Riverside is the newest of UC’s six medical schools. UC Merced (along with Berkeley, Santa Barbara, and Santa Cruz) does not have a medical school.

UC Recently Submitted Information on Merced Project. In September 2020, UC submitted information on the proposed project at the Merced campus. UC plans to construct a 116,750 assignable square foot building intended to support education and research‑related spaces. UC anticipates the project will cost $210 million. To date, UC has identified funding for $12 million of this cost ($7.8 million state cost and $4.2 million in campus reserves), covering the project’s preliminary planning phase. According to UC, it is still determining which fund sources would cover the remaining $198 million in project costs. The administration has not signaled whether it plans to include this proposal in its preliminary letter or whether it believes the project does not require any additional authorization beyond the language included in the 2019‑20 Budget Act.

Merced Project Raises Four Concerns. Each concern is described below.

- Project Scope Includes a Significant Amount of Research Space. The provisional language in the 2019‑20 Budget Act focused on authorizing a “medical school project.” Riverside’s project focused primarily on adding more instructional space for its medical school students. The proposed space at Merced, however, also includes a significant amount of research space and adds many more faculty offices, as shown in Figure 3. The inclusion of research space is what makes the overall cost of the project ($210 million) so high—more than double the Riverside medical school project.

- Project Scope Also Includes Substantial Space for Behavioral Sciences. Though the language envisioned a medical school building, the September proposal notes that much of the research space would support faculty in psychology and public health, two academic fields separate from professional medical education. According to Merced, these academic departments lack adequate space on the campus. This is despite the campus having recently completed the Merced 2020 project, a public‑private partnership that doubled the amount of its academic space.

- Project Financing Is Uncertain. Despite proposing to undertake such a costly project, UC has not identified a funding plan for most of the project (any of the costs beyond preliminary plans). Initiating a capital project without a funding plan is highly irregular and is poor budget practice. The lack of a funding plan is particularly concerning given the fiscal challenges facing the state, the UC system, and the Merced campus. For Merced specifically, staff noted to us in a discussion during the fall that the campus already has relatively high debt service levels following the completion of the Merced 2020 project.

- Planning Phases Are Costlier Than Is Typical. The combined preliminary planning and working drawings phases would total $34 million. This equates to 16 percent of total estimated project costs—higher than the average of around 10 percent of projects costs. The Merced project’s size and complexity may be a factor that is driving up costs for these initial phases.

Figure 3

UC Proposes Much Larger Building

at Merced Than at Riverside

Assignable Square Feet

|

Merced |

Riverside |

|

|

Instruction |

37,870 |

52,100 |

|

Research |

40,070 |

— |

|

Academic offices |

23,582 |

7,700 |

|

Student support |

3,200 |

5,200 |

|

Other |

12,028 |

— |

|

Totals |

116,750 |

65,000 |

Recommend Requesting UC Provide Stronger Justification for Specific Project Proposal. We think overseeing the UC Merced project at this early phase is especially important for ensuring that key legislative objectives are met in both the near and long term. Though the Legislature already has indicated interest in approving a medical school building at or near the UC Merced campus, several aspects of the specific project proposal may not align with original legislative objectives. In particular, the Legislature might have intended for (1) more of the proposed space to be dedicated to instruction, (2) more of the proposed space to be focused directly on medical education, (3) an explicit plan to secure funding for the project, and (4) planning costs that were at a more typical level. To the extent the Legislature shares these concerns about the project, we recommend it ask UC to respond, either by providing stronger justification for the existing proposal or adjusting the project proposal so that it is more in line with original legislative objectives.

Recommendations to Improve Project Review Process

Four Recommendations Designed to Improve Project Review Process. In the years since the state established the new project review and approval process, we have observed several weaknesses with this process. Below, we offer four recommendations that would increase transparency and strengthen legislative oversight, thereby potentially improving the overall quality of university projects. The recommendations would apply to both CSU and UC projects and entail statutory amendments. We recommend adopting the statutory changes this session but not making them operative until the next capital outlay review cycle (for 2022‑23 project proposals).

Recommend Requiring Public Posting of COBCP Material and Approval Letters. Currently, the administration does not publicly post the COBCP material that CSU and UC are required to submit for each project, nor does it post its February and April project approval letters. In contrast, DOF posts COBCPs for other agencies, including for the community colleges. The state also records approved projects for those agencies in the annual budget act. Publicly posting information about proposed and approved projects increases transparency, ensuring that the Legislature and the public have ready access to key details about each project. Consistent with these state practices, we recommend the Legislature amend statute to require the administration to publicly post COBCP material for CSU and UC projects, as well as its February and April project approval letters for the universities.

Recommend Clarifying Requirement to Provide List of Certain Projects. Like CSU’s infrastructure improvement proposal this year, UC has also submitted proposals in previous years that requested funding for an unspecified package of deferred maintenance projects. In these cases, the administration’s preliminary and final letters also have authorized funding without specifying the exact projects that would be undertaken. We think advance notification of which projects will be undertaken is a fundamental aspect of meaningful legislative review. We recommend the Legislature amend statute to clarify that the administration is to submit a list of specific infrastructure improvement and deferred maintenance projects that it approves as part of its preliminary and final approval letters. (In this recent university budget report, we make a similar recommendation regarding pay‑as‑you‑go deferred maintenance proposals.) To offer CSU and UC some flexibility to respond to changing infrastructure needs, the Legislature could consider further modifying statute in two ways. First, it could allow CSU and UC each to change a certain percentage (such as 10 percent) of the projects identified on their respective final approval letter, as long as the originally approved debt level is not exceeded. Second, it could require that CSU and UC document any of these changes in their February capital outlay progress reports to the Legislature.

Recommend Requiring Submission of Final Approval Letter No Later Than May Revision. While current law specifies that the administration’s final letter is to be submitted no sooner than April 1 (to allow some time for the Legislature to review the preliminary approval letter), it does not specify a deadline for final submission. We recommend the Legislature modify statute to require the administration to provide final project approval no later than the May Revision. We also recommend that the final approval letter contain only minor revisions to the preliminarily approved projects, rather than significant new proposals. (As discussed further below, significant new proposals still could be introduced through legislation, even if disallowed through the section letter process.) As the May Revision is close to the end of the budget process, the Legislature very likely would not have time to undertake meaningful review of new or substantially changed proposals. Equally important, having a final approval list no later than the May Revision would ensure the Legislature is aware of CSU’s and UC’s new debt‑service obligations before it adopts its final university General Fund support appropriations in the annual budget act. Knowing the level of these debt service obligations for CSU and UC is particularly important as those obligations are being paid using the universities’ support appropriations.

Recommend Significant, Substantive Changes to Project Proposals Be Made Through Legislation. Under the new project approval process, the administration has sometimes introduced significant new proposals after it submitted its preliminary approval letter to the Legislature. For example, for CSU in 2020‑21, the administration proposed notably increasing total project costs from the initial February letter, primarily by adding one new project and significantly changing the scope of another project. Moreover, DOF did not notify the Legislature of these changes until June 30—after the Legislature had enacted the budget. Proposing such notable changes so late in the budget process gave the Legislature effectively no time to review them publicly. To ensure the Legislature has a meaningful opportunity to review future project proposals, we recommend the Legislature amend statute to require that any significant changes the administration proposes after the February preliminary approval letter be introduced in legislation. (“Significant changes” could include proposals that add projects, significantly expand the scope of projects, or substantially increase project costs and associated state‑funded debt.)