February 1, 2021

The 2021-22 Budget

Analysis of the Major University Proposals

- Introduction

- Impact of Pandemic

- Overview of Governor’s Budget

- Base Support

- Enrollment

- Student Support

- Faculty Professional Development

- Deferred Maintenance

Summary

In this report, we first examine how the pandemic has affected the California State University (CSU) and the University of California (UC), then analyze the Governor’s major university budget proposals. Below, we share some of the key takeaways from the report.

Adverse Fiscal Impacts of Pandemic Have Led Universities to Adjust Budgets. Due to the pandemic, CSU and UC have experienced substantial revenue declines in their noncore programs, a reduction in state General Fund support, and some higher than normal costs. Although the universities have received federal relief funds and taken actions to contain their spending, they report having operating deficits in 2020‑21.

Base Increases Could Be Considered but Final Levels Set in May. The Governor’s budget proposes to provide CSU and UC each 3 percent base General Fund increases in 2021‑22, along with certain other targeted ongoing augmentations. In total, CSU would receive an additional $202 million in ongoing General Fund support and UC would receive $136 million. These increases would partly, but not entirely, restore the universities to their pre‑pandemic levels. CSU and UC would each remain more than $100 million below their 2019‑20 levels. Given all of the factors affecting the universities, we think providing them base increases merits consideration. The Legislature, however, may wish to wait until May when updated revenue information will be available before finalizing its decisions in this area.

Base Expectations Could Be Revisited and Refined. As a condition of receiving the 3 percent base General Fund increases, the Governor would require CSU and UC to (1) develop a plan for eliminating student equity gaps by 2025, (2) adopt policies to sustain online education at a level that is at least 10 percentage points higher than 2018‑19 levels, and (3) create a dual admissions pathway with the community colleges. Though we believe the Governor has identified areas of common concern with the Legislature, we recommend making certain improvements to each of these proposals. We generally think the Legislature could strengthen oversight of the universities’ performance in these areas while avoiding the drawbacks of the Governor’s proposals (such as the arbitrary benchmark relating to online education).

Student Support Proposals Could Be Better Coordinated. The Governor has five proposals in the area of student support—signifying one of his main university budget priorities. The proposals total $90 million ($45 million ongoing and $45 million one time). They provide funding for students’ basic needs (including food and housing), mental health, access to technology, and emergency grants. Although the Governor has a laudable focus on issues that have been exacerbated by the pandemic, he continues the state’s piecemeal approach to addressing those issues—even adding new programs to a hodgepodge of existing ones. We recommend the Legislature clarify the objectives of each student support program before approving additional ongoing funding. Longer term, we encourage the Legislature to take a more holistic approach in coordinating traditional student financial aid programs, basic needs programs, and other public assistance programs.

Introduction

This report analyzes the Governor’s major budget proposals for CSU and UC. We begin the report with a review of what is known to date about the impacts of the pandemic on the universities’ budgets. We then describe the Governor’s overall budget plans for the universities. Next, we analyze the Governor’s specific university proposals, with sections focused on base support, enrollment, student support, faculty professional development, and deferred maintenance. We plan to cover a few remaining proposals—for example, ones relating to UC medical education—in subsequent analyses. We provide tables detailing each segment’s budget on our EdBudget website.

Impact of Pandemic

Campuses Have Operated Remotely Since Start of Pandemic. In response to the public health crisis, all 23 CSU campuses and 10 UC campuses (as well as all California Community Colleges) shifted primarily to remote operations beginning in March 2020. Campuses continue to offer the vast majority of their instruction online, with the exception of a small number of courses that involve laboratory or other required hands‑on work. In addition, campuses are providing most of their student services (such as academic advising, financial aid administration, and mental health services) online. Institutions tend to be operating their noncore programs (including their housing, dining, and parking programs) at substantially reduced capacity.

Pandemic Is Having Adverse Fiscal Impact on Universities and Students. As Figure 1 shows, the total estimated fiscal impact from March through December 2020 is $1.1 billion at CSU and $1.9 billion at UC (excluding its medical centers and medical schools). The most significant fiscal impact for campuses at both segments has been revenue declines, which have resulted from operating at reduced capacity. Revenue declines have been particularly acute for the segments’ self‑supporting noncore programs (including their housing programs). Campuses also have experienced declines in core funding (state General Fund and student tuition revenue). Additionally, campuses have incurred some extraordinary costs, including higher technology costs and costs for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) testing and protective equipment. As with campuses, some students are facing extraordinary challenges, including reduced household income, higher technology costs, and disruptions in housing arrangements.

Figure 1

Universities Are Reporting Substantial

Revenue Declines Due to Pandemic

Cumulative Adverse Fiscal Impact

From March Through December 2020

|

CSU |

UC |

|

|

Funding Reductions |

||

|

Noncore funds |

$689 |

$1,384 |

|

State General Fund |

299 |

302 |

|

Tuition revenue |

24 |

38 |

|

Subtotals |

($1,012) |

($1,724) |

|

Extraordinary Costs |

$70 |

$150 |

|

Totals |

$1,082 |

$1,874a |

|

aUC also reports funding reductions of $1.1 billion and extraordinary costs of $361 million from its medical centers and medical schools. |

||

Federal Government Has Provided Some Fiscal Relief. One source of assistance for the universities and students has been federal relief funding. The federal government provided higher education institutions with relief funding shortly after the onset of the pandemic (in spring 2020) and is set to provide a second round of relief funding in winter 2021. (See our posts, Overview of Federal Higher Education Relief and Second Round of Federal Higher Education Relief Funding, for more detail.) As Figure 2 shows, federal relief funding across the two rounds totals $1.4 billion for CSU campuses and $658 million for UC campuses. Both rounds designate a portion of federal funding for emergency student financial aid, with the rest available for campus operations. Campus relief funds can be used for an array of expenses, including health and safety measures, technology, professional development, and backfilling revenue declines in noncore programs.

Figure 2

Second Round Provides More

Federal Relief Funding Than First Round

(In Millions)

|

CSU |

UC |

|

|

CARES Act |

||

|

Student aid |

$263 |

$130 |

|

Campus relief |

263 |

130 |

|

Supplemental reliefa |

38 |

7 |

|

Subtotals |

($564) |

($267b) |

|

CRRSAA |

||

|

Student aid |

$263 |

$130 |

|

Campus relief |

591 |

261 |

|

Subtotalsc |

($854) |

($391) |

|

Totals |

$1,418 |

$658 |

|

aCan be used for either student aid or campus relief. bExcludes $861 million in CARES Act relief funds for UC medical centers. cAs of this writing, CRRSAA supplemental relief for campuses and relief for UC medical centers not yet been announced. |

||

|

CARES Act = Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (enacted in late March 2020) and CRRSAA = Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (enacted in late December 2020). |

||

Overview of Governor’s Budget

Governor’s Budget Partly Restores General Fund Support for Universities. As Figure 3 shows, the Governor’s budget proposes a total of $7.8 billion in ongoing funding for the universities. This level of support is an increase of $338 million (4.5 percent) over the level in 2020‑21, with larger growth at CSU than at UC. Ongoing funding, however, would remain below pre‑pandemic General Fund levels, with 2021‑22 funding below the 2019‑20 level by $232 million (2.9 percent). In addition to ongoing support, the Governor’s budget includes $450 million one‑time General Fund for the universities ($225 million for each segment).

Figure 3

Governor’s Proposed General Fund Support Reflects Partial Restoration

Ongoing General Fund Support (In Millions)

|

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

Change From 2020‑21 |

Change From 2019‑20 |

||||

|

Amount |

Percent |

Amount |

Percent |

|||||

|

CSU |

$4,352 |

$4,042 |

$4,243 |

$202 |

5.0% |

‑$109 |

‑2.5% |

|

|

UC |

3,724 |

3,465 |

3,601 |

136 |

3.9 |

‑123 |

‑3.3 |

|

|

Totals |

$8,076 |

$7,507 |

$7,845 |

$338 |

4.5% |

‑$232 |

‑2.9% |

|

Governor’s 2021‑22 Proposals Revolve Around a Few Areas. As Figure 4 shows, the largest ongoing proposals provide 3 percent general‑purpose base increases and, for CSU only, adjustments for retirement benefit costs. The bulk of the proposed one‑time funding would support deferred maintenance projects. Several of the remaining proposals focus on providing additional support for students and faculty.

Figure 4

Governor Has Similar Budget Priorities for

CSU and UC

2021‑22 (In Millions)

|

Proposals |

CSU |

UC |

|

Ongoing Proposals |

||

|

Base increase (3 percent) |

$112 |

$104 |

|

Retirement benefitsa |

57 |

— |

|

Student mental health and technology |

15 |

15 |

|

Student Basic Needs Initiative |

15 |

— |

|

Programs in Medical Education (PRIME) |

— |

13 |

|

Other |

3 |

4 |

|

Subtotals |

($202) |

($136) |

|

One‑Time Initiatives |

||

|

Deferred maintenance |

$175 |

$175 |

|

Emergency student financial aid |

30 |

15 |

|

California Institutes for Science and Innovation |

— |

20 |

|

Faculty professional development |

10 |

5 |

|

Other |

10 |

10 |

|

Subtotals |

($225) |

($225) |

|

Totals |

$427 |

$361 |

|

aConsists of adjustments for retiree health ($55 million) and pension contributions ($2 million). |

||

Base Support

In this section, we first provide background on how CSU and UC responded to core funding reductions in 2020‑21. We then describe the Governor’s proposal to increase university base support in 2021‑22. The Governor links his proposed increase in CSU and UC base support to three expectations relating to student equity gaps, online education, and dual admissions. We analyze each of these expectations in turn. We end with a discussion about tuition.

Background

State Enacted Base Reductions to the Universities in 2020‑21. Following several years of the state providing CSU and UC with General Fund base augmentations, the 2020‑21 Budget Act reduced state funding for the universities. These reductions were part of a broader state budget package intended to address a substantial projected shortfall in General Fund revenues. As Figure 5 shows, the reductions in ongoing General Fund support at CSU and UC were 6.9 percent and 8.1 percent, respectively, from 2019‑20 levels. CSU’s reduction, however, was slightly larger in terms of total core funding, as General Fund support comprises a larger portion of core funding at CSU than at UC. Whereas CSU’s reduction in terms of total core funding was 3.9 percent, it was 3.3 percent at UC.

Figure 5

State Reduced Base Support for the

Universities in 2020‑21

General Fund Reductions From 2019‑20 Ongoing Levels

|

Amount |

Percent |

|

|

CSU |

$299.0 |

6.9% |

|

UC |

$302.4 |

8.1% |

|

Campuses |

259.2 |

7.7 |

|

Office of the President |

27.3 |

12.7 |

|

Agriculture and Natural Resources |

9.2 |

12.7 |

|

UCPatha |

6.7 |

12.7 |

|

aGeneral Fund reduction was offset by a $31.5 million increase in campus assessments. Overall support for UCPath increased $24.8 million (37 percent). |

||

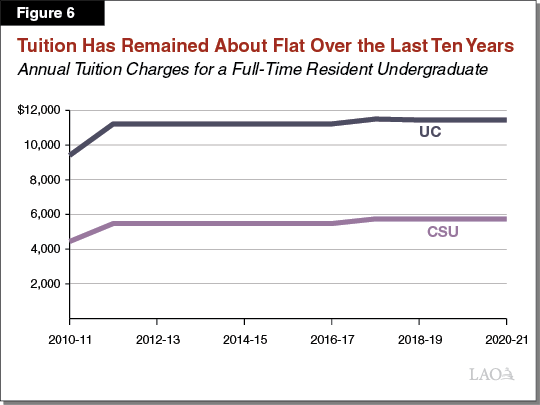

Universities Did Not Increase Tuition to Offset State Reductions. Neither CSU nor UC increased student tuition to help offset the declines in 2020‑21 state funding. As Figure 6 shows, resident undergraduate tuition has remained about flat over the past ten years, only increasing once since 2011‑12. Though the universities kept tuition charges flat in 2020‑21, they experienced a drop in overall tuition revenue largely resulting from declines in nonresident enrollment. CSU estimates a $24 million reduction in tuition revenue from 2019‑20 to 2020‑21, whereas UC estimates a $38 million drop.

CSU Is Allocating Some Federal Relief Funds for Core Operations. In discussions with our office, both universities emphasized that they are using the bulk of their federal campus relief funds to address revenue declines in their noncore programs and cover extraordinary costs related to COVID‑19. According to staff at the Chancellor’s Office, CSU campuses are allocating at least a portion of their federal campus relief funds to assist their core programs. Any federal relief funding allocated either to noncore or core programs is available only on a one‑time basis.

Universities Have Taken Several Actions to Respond to Fiscal Challenges. Given core funding reductions, both CSU and UC have sought to reduce their core spending by holding a portion of faculty and staff positions vacant (that is, suspending most hiring) and forgoing general salary increases for most employee groups. Campuses also have seen savings as a result of reduced employee travel and utility costs. Nonetheless, both segments report that these strategies have been insufficient to fully address their core funding reductions, and campuses have had to draw down funds from their reserves. As of this writing, the CSU Chancellor’s Office reports that campuses plan to draw down a total of roughly $200 million from their core operating reserves in 2020‑21 (about half of its estimated uncommitted core reserves at the end of 2019‑20). The UC Office of the President reports that UC campuses plan to draw down as much as $174 million (about 65 percent of its estimated uncommitted core reserves at the end of 2018‑19, the most recent year of information available). (As we discuss in An Analysis of University Cash Management Issues, UC also borrowed externally in 2020‑21 to help it cover both its noncore and core operating expenses.)

Base Increases

Governor Proposes Base Increases. The Governor proposes providing ongoing augmentations of $112 million to CSU and $104 million to UC, reflecting 3 percent General Fund increases over 2020‑21 levels. These proposed increases partially restore the universities to their 2019‑20 levels. In addition to the 3 percent base increase, the budget would provide a $57 million augmentation for CSU pension and retiree health cost increases, resulting in a total ongoing base augmentation of $169 million. (Unlike CSU, UC would have to accommodate retirement benefit cost increases from within its 3 percent base augmentation.)

First Call on Base Augmentation Likely Is Covering Increases in Certain Operating Costs. Like most government agencies, the universities tend to experience operating cost increases each year, such as rising pension and health care costs. For CSU, most of these types of cost pressures are driven by requirements in state law and other external factors, such that campuses have little flexibility to directly affect these costs. Relative to CSU, UC has somewhat greater flexibility to adjust the policies driving these cost pressures. For example, UC determines the share of health premiums it subsidizes for employees and retirees. It also sets its own policies determining the size of pension benefits for new employees and its annual employer contribution. (Though UC has greater flexibility in setting its own pension policies, reducing its employer contribution rate would slow its progress in fully funding its pension system and increase out‑year cost pressures.) Based on information provided by the segments and the administration, we estimate these types of operating costs will increase by $114 million at CSU and $76 million at UC. (We include pension and health care cost increases for both segments, along with a few other segment‑specific costs involving debt service, facility maintenance, and new statutory requirements.)

Salaries Are Another Cost Pressure Facing the Universities. After covering benefits and debt‑service payments, the universities typically face decisions about salaries. In its budget plan for 2021‑22, CSU does not anticipate funding general salary increases for any employee group. For most employee groups, the CSU Chancellor’s Office has negotiated two‑year contract extensions through 2021‑22 that do not provide salary increases. (One employee group—the California Faculty Association—has a contract extension that expires at the end of 2020‑21.) While UC’s 2021‑22 budget plan also forgoes salary increases for many employee groups, the plan anticipates salary growth of $82 million to fund previously agreed upon increases for represented employee groups, faculty merit increases, and a 1.5 percent general salary increase for certain nonrepresented staff.

Universities Likely Would Use Remaining Funds for Restoration. After weighing salary decisions, campuses likely would prioritize restoring some of the reductions they incurred in 2020‑21. Most notably, campuses likely would resume some hiring in 2021‑22—filling a portion of vacant faculty and staff positions. These hires could support some combination of more courses and more student support services. Campuses also might consider undertaking more building maintenance projects in 2021‑22. As base General Fund support would remain below pre‑pandemic levels under the Governor’s budget, campuses likely would not be able to fully fund all of these priorities, absent further drawing down their reserves.

State Budget Has Limited Capacity for Giving Universities Additional Ongoing Funding. While the fiscal challenges currently facing the universities suggest that more ongoing base support than the Governor’s proposed level could be warranted, the state’s ability to expand ongoing CSU and UC support is limited. As we noted in The 2021‑22 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Budget, we and the administration project annual state operating deficits that grow over the outlook period. Specifically, the administration anticipates state operating deficits of $7.6 billion in 2022‑23, growing to $11.3 billion by 2024‑25.

Consider Proposed Base Increases as Starting Point. The proposed 3 percent base increases could serve as a starting point for legislative deliberations. The 3 percent increases would help the universities cover some increases in their operating costs and leave some funding remaining for salary and staffing increases while still being attentive to the state’s tight fiscal outlook. In May, the Legislature will get updated state revenue estimates and be in a better position to assess the state’s ongoing budget capacity. In light of that updated information, the Legislature then could revisit the size of the proposed university base increases. Regardless of the level of support the Legislature ultimately decides to provide, it could consider adopting language having each segment report key information about its budget plans in the fall. Specifically, such reports could include each segment’s projected core funding, spending by program area, operating deficits, budget reserves, and specific actions taken to implement budget plans. These reports could help the Legislature keep better apprised of how the segments are responding to remaining fiscal challenges.

Student Equity Gaps

Governor Sets Student Equity Goals for the Segments. As a condition of receiving base increases in 2021‑22, the Governor proposes requiring CSU and UC to submit by June 30, 2022 multiyear plans to reduce their student equity gaps by 20 percent each year, fully eliminating them by 2025. The administration indicates the plans would need to focus on eliminating longstanding achievement gaps among student racial/ethnic groups and socioeconomic groups. The proposed budget bill language does not specify exactly how equity gaps are to be measured, but it directs the segments to establish common metrics.

Proposal Focuses on a Longstanding Issue. As Figure 7 shows, both CSU and UC have notable student achievement gaps by race/ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status. Both the CSU Board of Trustees and the UC Board of Regents have expressed concern over student achievement gaps and developed multiyear plans to eliminate them. CSU’s plan aims to eliminate gaps by 2025, whereas UC’s plan aims to eliminate gaps by 2030. The Legislature also has sought to raise attention to student equity gaps—for example, by requiring the universities to submit performance reports each March that contain data on persistence and graduation rates for low‑income students and their peers. The Governor’s proposal further elevates gaps among student racial/ethnic and socioeconomic groups to be of state‑level concern.

Figure 7

Universities Have Notable Gaps in Graduation Rates

Rates for First‑Time, Full‑Time Freshman

|

CSU |

UC |

||||

|

Four Year |

Six Year |

Four Year |

Six Year |

||

|

Race/Ethnicity |

|||||

|

White |

43% |

70% |

73% |

87% |

|

|

Asian/Pacific Islander |

29 |

68 |

76 |

89 |

|

|

Latino |

21 |

57 |

58 |

79 |

|

|

Black |

16 |

48 |

54 |

77 |

|

|

Gender |

|||||

|

Female |

32% |

65% |

74% |

88% |

|

|

Male |

22 |

58 |

64 |

83 |

|

|

Financial Status |

|||||

|

Not a Pell Grant recipient |

36% |

67% |

74% |

87% |

|

|

Pell Grant recipient |

20 |

57 |

63 |

83 |

|

|

Note: Four‑year data is for entering 2015 cohort. Six‑year data is for entering 2013 cohort. |

|||||

Establishing Explicit State Equity Goals Could Be Beneficial. In recent years, the state has taken a number of steps to improve student outcomes at CSU and UC, but it has not yet set any specific performance goals. The absence of explicit goals makes it difficult for the Legislature to hold the universities accountable for their performance. Adopting goals, including equity‑based goals such as the ones proposed by the Governor, could foster greater transparency and accountability—helping to concentrate attention and resources on key areas.

Governor’s Expectation Is More Ambitious Than UC’s Internal Equity Plan. For CSU, the Governor’s equity goals align with the goals CSU already has established through its multiyear equity plan. By comparison, the Governor’s goals would have UC accelerating its equity plan. UC has expressed some concern with the accelerated time line, particularly given the absence of additional state funds to reach the more ambitious goals. To fulfill the Governor’s expectations, UC campuses likely would have to redirect resources from other operating areas to enhance its student support services.

As Proposal Lacks Repercussions for Falling Short, Legislative Oversight Will Be Key. One or both of the segments might fall short of eliminating their student equity gaps by 2025. The Governor’s proposal, however, contains no repercussions were the universities not to meet the established equity goals. Thus, it likely would fall on the Legislature to regularly review the universities’ performance in this area and consider appropriate responses, whether budget or policy responses. Reviewing university performance over the next several years could be especially important, as the pandemic, shift to remote operations, and recent budget shortfalls might have exacerbated student equity gaps. Since the onset of the pandemic, disadvantaged students are more likely to have had difficulty accessing computers, reliable internet connectivity, and quiet workspace. Some high school students also might be entering college somewhat less well prepared than in the recent past. By regularly interacting with the universities to examine their student equity outcomes and strategies, the Legislature would be better positioned to make midcourse policy and budget adjustments.

Adopt Equity Goals but Strengthen Oversight. Were the Legislature supportive of the Governor’s equity goals, we recommend enhancing associated legislative oversight. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature modify the existing March university performance reports to include the common equity‑gap metrics that are developed. As part of these March reports, the Legislature also could direct the segments to provide revised goals, time lines, and implementation plans were they to be found falling short of meeting established equity goals.

Online Education

Governor Proposes That Universities Sustain a Higher Level of Online Education. The Governor also links his proposed base increases for the universities to a requirement that they adopt policies by June 30, 2022 designed to maintain the share of their online courses and programs at a level that is at least 10 percentage points higher than their share in 2018‑19.

Expanding Online Education Has Key Trade‑Offs. Online education has at least two key benefits. First, online courses can provide a more flexible learning environment, enabling more placebound students, working adults, and other nontraditional student groups to attend college and complete courses. Second, online courses can mitigate demand for on‑campus classrooms and other instructional spaces. Online courses, however, can have drawbacks. For example, research suggests that online courses tend to have lower completion rates than in‑person instruction, and gaps are greater for Black and Latino students. Partly in response to both these perceived benefits and drawbacks, the state began funding efforts to improve online education several years ago. For example, the 2013‑14 budget provided each university segment $10 million ongoing General Fund to create new online courses, encourage faculty participation in teaching online courses, and provide associated faculty professional development.

Pandemic Led to Opportunities for Exploring New Ways of Delivering Instruction. With the sudden move to large‑scale remote instruction necessitated by the pandemic, campuses, faculty, and students have had to adapt to new ways of teaching and learning. These experiences could provide the Legislature useful data as to which courses were particularly well suited to online formats, what barriers faculty and students faced, and the costs campuses incurred to transition courses from in‑person to online formats.

Proposed Requirement Is Arbitrary and Lacks Justification. Despite the potential benefits of expanding online education, we have a few concerns with the Governor’s specific proposal. First, the administration has not justified whether the proposed 10 percentage point increase is warranted given student demand for online courses and campus facility issues. Second, all campuses, regardless of their baseline, are expected to increase their online offerings by the same percentage point. A more refined analysis might indicate a higher or lower level of online education is warranted at any particular campus. Without a clearer rationale for setting online enrollment targets, campuses could make poor decisions that work counter to promoting student success. For example, arbitrary increases in online courses potentially could work counter to the Governor’s proposed expectation to eliminate equity gaps.

Reject Online Education Proposal and Direct Segments to Instead Report Key Baseline Information. Given the arbitrariness of the proposed 10 percentage point increase in online courses, we recommend rejecting the Governor’s proposal. However, we understand the administration’s desire to maintain the current momentum toward developing and improving online courses. To this end, we recommend the Legislature instead adopt budget bill language directing the universities to report on their experiences with online education. Such a report should include: (1) data on pre‑pandemic enrollment in online courses for each campus, (2) analysis as to which courses are most suitable for online instruction, (3) an estimate of the fiscal impact of expanding online education, (4) a plan for improving student access and outcomes using technology, and (5) an assessment of the need for additional faculty professional development. To ensure this information is available to assist next year’s budget deliberations, we recommend requiring the universities to submit this information by November 2021. Such a report would give the Legislature a better basis to determine how to support online education at the universities in the coming years.

Dual Admissions

Governor Proposes a Dual Admission Pathway. A third condition of the Governor’s proposed base increases for the universities is that they create a dual admissions pathway with the community colleges. Under the new pathway, recent high school graduates could apply and be admitted to CSU and UC campuses but would start and complete their lower‑division coursework at a community college. The administration does not propose a target number of students who would qualify for this new pathway, but the proposed budget bill language calls for roughly half of the dual admits to meet CSU or UC’s existing freshman admission requirements. The remaining half of dual admits would be conditionally admitted to a CSU or UC campus, with their eventual university enrollment dependent on their academic performance in community college coursework. According to the administration, a dual admission pathway would be intended to accomplish several objectives, including expanding access for underrepresented and placebound students, reducing student costs, improving student outcomes, and simplifying the transfer process.

Proposal Aims to Address Shortcomings With Transfer Process. Historically, community college students have had to navigate a complex and confusing array of academic pathways and course expectations to successfully transfer to CSU and UC. This complexity can cause students to accumulate excess units at the community college level, repeat courses once they arrive at CSU or UC, and discourage some students altogether from transferring. In discussions with our office, the Department of Finance (DOF) emphasized several ways a dual admission policy could reduce this complexity for students. For example, high school graduates could receive greater clarity as to what is required of them to enroll at CSU and UC. The administration also noted that the dual admission policies could necessitate greater coordination between community colleges and CSU and UC campuses, potentially improving the quality of advising and other student services.

Proposal Aims Specifically to Streamline UC Transfer Pathways. In 2010, the state sought to simplify transfer between community colleges and CSU by creating the “associate degrees for transfer.” These degrees establish a common set of lower‑division course requirements across community college and CSU campuses, and they guarantee community college students not only admission to the CSU system but the ability to complete their bachelor’s degree with 60 units of upper‑division coursework. While this effort has helped simplify the process for students interesting in attending CSU, these degrees do not offer the same guarantees for students interested in attending UC. In 2018, the UC Office of the President entered into an agreement with the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office to pilot UC‑specific associate degrees for transfer in biology and chemistry. These UC‑specific degrees have many similarities, but are not identical, to the CSU‑specific degrees. To further these recent efforts, the Governor’s proposed expectation would direct UC either to develop UC‑specific degrees in more subject areas or accept the existing CSU‑specific transfer degrees in these areas. Such an approach has the potential to further simplify the transfer process to UC, as well as better align UC and CSU pathways.

Dual Admission Pathway Comes With Risks. Though a dual admission pathway has potential benefits, it also has potential drawbacks—possibly working at cross‑purposes with the state’s recent efforts to simplify the transfer process. For example, if only a portion of students are eligible for dual admission as freshmen, then all other interested community college transfer students would still need to navigate one or more of the myriad other transfer pathways. Depending on how universities implement the dual admission policy, the new pathway also could disproportionally benefit certain community college students. For example, a few community colleges typically account for a disproportionate share of transfer students. Depending upon how it would work, a dual admission pathway might further benefit those community college campuses that already have well‑established relationships with certain CSU or UC campuses.

More Information Is Needed to Fully Assess Proposal. According to DOF, the administration plans to submit trailer bill legislation in the coming weeks with more detail about the proposal. Currently, key details are lacking. In particular, the administration should provide greater clarity regarding: (1) the portion of high school graduates who would be eligible for dual admission, (2) how the new dual admission pathway would interact with the existing transfer pathways available to students, (3) whether the pathways would be developed at the systemwide level or by each CSU and UC campus, and (4) whether the new associated degrees relating to UC would benefit only students in the dual admission pathway or all interested transfer students. We withhold making a recommendation on this proposal until these details are available. Upon receiving more information, we could provide a further analysis of the more fully developed proposal.

Tuition Expectations

Governor Expects Universities to Hold Tuition Flat. The Governor’s Budget Summary indicates the administration’s intent that CSU and UC hold resident undergraduate tuition levels flat in 2021‑22. While the proposed budget bill does not explicitly contain this expectation, the bill maintains language from the previous three budget acts establishing repercussions were the universities to increase tuition. Specifically, this language authorizes DOF to reduce General Fund support for the universities were they to increase resident undergraduate tuition levels. The reduction is tied to the additional cost for state financial aid programs resulting from the tuition increase.

Increasing Tuition Could Expand Budget Capacity. Increasing tuition could expand the state’s budget capacity in one of two ways: by supplementing state funding increases for the universities or by freeing up state funding for high priorities in other areas of the budget. Given the fiscal challenges facing campuses and the state’s limited capacity to fully restore the universities’ ongoing support, tuition increases could be a key option for the universities and the state to consider in the coming years.

Financial Aid Typically Covers Tuition for Low‑Income Students. One key consideration surrounding tuition increases is the financial impact on California students. For students with financial need (typically low‑income and many middle‑income students), state and university financial aid programs are designed to fully cover tuition, including any tuition increases. Because of these policies, higher‑income students are the ones to bear the cost of tuition increases.The Move to Remote Instruction Has Raised Questions About Tuition Levels. As universities around the nation have moved to remote instruction, new considerations have emerged around tuition setting. Some universities, particularly highly selective private ones, adopted tuition increases for the 2020‑21 academic year, likely in recognition that their underlying cost structures had not fundamentally changed. Faculty remained teaching and facilities continued to be maintained, even if operating at reduced capacity. In contrast, other institutions (including CSU and UC) elected to hold tuition flat, perhaps feeling that during the pandemic was a poor time to increase student charges. Some institutions even offered discounts to their students, perhaps recognizing that students were needing to adapt to instructional modes they might otherwise not have chosen. The Legislature, the CSU Board of Trustees, and the UC Board of Regents likely will want to weigh all of these considerations as they contemplate future tuition decisions.

Enrollment

In this section, we focus on enrollment at the universities. We begin by providing background on recent enrollment practices and trends. We then describe the Governor’s approach to enrollment this year, which we follow with our analysis and recommendations were the Legislature to want to pursue potential enrollment growth at CSU and UC.

Background

State Often Sets Enrollment Targets for the Universities. In most years, the state budget has established systemwide resident enrollment targets for CSU and UC. When these targets require enrollment growth, the state typically provides associated General Fund augmentations. Historically, the state has set targets for the upcoming academic year, but some recent budgets have set the targets for the following year (for example, setting a target in the 2019‑20 budget for the 2020‑21 academic year). Setting an out‑year target allows the state to better influence admission decisions, as the universities typically have already made their decisions for the upcoming academic year before the enactment of the state budget in June. Since 2015‑16, five of the last six budgets have set enrollment targets for the universities, with one of these budgets setting an out‑year target for CSU and four of these budgets setting out‑year targets for UC.

State Did Not Set Targets in the 2020‑21 Budget. Deviating from the state’s recent practice, the 2020‑21 budget did not include CSU or UC enrollment targets for either the 2020‑21 or 2021‑22 academic years. In the case of CSU, the Chancellor’s Office was left to determine the number of resident students to enroll in 2020‑21. Though UC did not face any new enrollment expectations in the 2020‑21 budget, the 2019‑20 budget provided UC funding to enroll 4,860 more resident undergraduate students in 2020‑21 over the level in 2018‑19. UC reports that it has met the 2020‑21 target, as discussed further below.

Overall Resident Enrollment Increased in Fall 2020. As Figure 8 shows, total resident enrollment increased from fall 2019 to fall 2020 at both CSU and UC. The trends in the underlying composition of enrollment, however, varied across the two university systems. At CSU, for undergraduates, new enrollment was virtually flat, but continuing enrollment grew. Graduate enrollment also grew, entirely due to growth in new students. In contrast, at UC, new undergraduate enrollment grew and new graduate enrollment declined. While the universities’ overall resident enrollment increased in fall 2020, nonresident enrollment decreased, as the box below describes in more detail. (In addition to the fall‑to‑fall growth, UC experienced a notable increase in enrollment during the summer 2020 term. After factoring in this summer growth, UC anticipates exceeding its 4,860 student growth target for 2020‑21.)

Figure 8

CSU’s and UC’s Trends in New and Continuing Resident Enrollment Differ

Fall Resident Headcount

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

Change From 2019 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

CSU |

|||||

|

Undergraduate |

|||||

|

New |

115,450 |

119,018 |

119,194 |

176 |

0.1% |

|

Continuing |

291,673 |

290,939 |

294,616 |

3,677 |

1.3 |

|

Subtotals |

(407,123) |

(409,957) |

(413,810) |

(3,853) |

(0.9%) |

|

Graduate |

|||||

|

New |

17,565 |

17,494 |

20,360 |

2,866 |

16.4% |

|

Continuing |

29,274 |

28,886 |

28,646 |

‑240 |

‑0.8 |

|

Subtotals |

(46,839) |

(46,380) |

(49,006) |

(2,626) |

(5.7%) |

|

Totals |

453,962 |

456,337 |

462,816 |

6,479 |

1.4% |

|

UC |

|||||

|

Undergraduate |

|||||

|

New |

54,910 |

54,326 |

56,918 |

2,592 |

4.8% |

|

Continuing |

128,035 |

131,340 |

130,528 |

‑812 |

‑0.6 |

|

Subtotals |

(182,945) |

(185,666) |

(187,446) |

(1,780) |

(1.0%) |

|

Graduate |

|||||

|

New |

6,760 |

6,885 |

6,783 |

‑102 |

‑1.5% |

|

Continuing |

24,263 |

24,495 |

24,527 |

32 |

0.1 |

|

Subtotals |

(31,023) |

(31,380) |

(31,310) |

(‑70) |

(‑0.2%) |

|

Totalsa |

213,968 |

217,046 |

218,756 |

1,710 |

0.8% |

|

aExcludes postbaccalaureate enrollment, for which new and continuing breakouts are not available. In fall 2020, UC enrolled a total of 134 resident postbaccalaureate students—10 fewer students than in fall 2019. |

|||||

University Nonresident Enrollment Declined in Fall 2020

Of the approximately 482,000 students the California State University (CSU) served in fall 2019, 25,600 (5.3 percent) were nonresidents. In fall 2020, new nonresident undergraduate enrollment at CSU declined by 7.9 percent. The decline in new nonresident graduate enrollment was greater, at 40 percent. Nonresident enrollment comprises a larger share of total enrollment at the University of California (UC). Of the approximately 285,100 students UC served in fall 2019, 58,700 (21 percent) were nonresidents. Though nonresident enrollment also dropped at UC in fall 2020, the declines were smaller. New nonresident undergraduate enrollment dropped by 7.2 percent and new nonresident graduate enrollment dropped by 18 percent. At both segments, the declines were primarily due to notable drops in the number of new international students.

Proposals

Governor Does Not Propose Enrollment Targets for CSU or UC. The Governor’s 2021‑22 budget does not set specific enrollment expectations for either university system for either 2021‑22 or 2022‑23. In the absence of these targets, the universities would have flexibility to make their own enrollment decisions over the next couple of months for the 2021‑22 academic year. The universities also likely would set their own targets to guide their fall 2022 admission decisions.

Assessment

Setting Enrollment Targets Is a Key Responsibility of the State. Though the Governor proposes connecting base funding in 2021‑22 to expectations related to student equity gaps, online instruction, and dual admissions, he does not propose establishing enrollment expectations. Without such expectations, the Legislature would not have clarity regarding how many students the universities are to serve. This approach would generate confusion for both the state and the universities and could lead to contending objectives and muddled accountability.

State Could Still Influence Fall 2022 Admission Decisions. In addition to the importance of setting clear expectations, we think the state’s practice of setting those expectations for the following academic year has merit. Because of the timing of campuses’ admission decisions, the state has already lost most of its ability to influence fall 2021 admission decisions. By setting a target for the 2022‑23 academic year, however, the state could still influence campuses’ upcoming admission decisions.

Several Factors Suggest Overall Enrollment Demand Is Uncertain. As the Legislature weighs how much enrollment to expect from the universities, one factor usually under consideration is overall student demand to attend the universities. Many competing factors likely will affect CSU and UC enrollment demand in the coming years, including:

- High School Graduates. DOF projects the number of high school graduates in California to increase by 1.4 percent in 2020‑21 (affecting fall 2021 demand) and by 0.3 percent in 2021‑22 (affecting fall 2022 demand). An increase in the number of high school graduates increases the number of students who are eligible to enroll at CSU and UC as freshmen.

- Community College Students. New community college transfer enrollment has been steadily increasing at both universities, and it continued to grow in fall 2020. The trends at the universities are associated with increases in community college transfer‑level course enrollment. In 2020‑21, overall community college enrollment is down, which could have implications for university transfer enrollment over the next few years. How community college enrollment might rebound in the aftermath of the pandemic, however, is uncertain.

- Economy. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, California’s unemployment rate increased from around 4 percent in February 2020 to over 16 percent in April 2020. While the rate has fallen since then, the most recent estimate (9 percent in December 2020) remains above pre‑pandemic levels. Student demand for the universities (at the undergraduate and graduate levels) might be affected by these economic trends, but the precise impact they might have at CSU and UC over the next few years is not known.

- Return to In‑Person Instruction. Both universities have announced plans to resume in‑person instruction in fall 2021, assuming the state and nation have made sufficient progress to curb the pandemic. The impact of resuming in‑person instruction on enrollment demand is not yet known. Some students may have deferred enrolling in college during the pandemic and opted to wait until in‑person instruction resumed. As both segments did not experience notable resident enrollment declines in fall 2020, however, this impact may not be significant.

Longstanding Eligibility Policy Might Suggest Enrollment Growth Is a Lower Priority. Historically, the state has expected CSU to draw its freshman admits from the top 33 percent of the state’s high school graduates, with UC drawing from the top 12.5 percent. As we have noted in previous analyses, CSU and UC have been found to be drawing from beyond these pools in recent years, and likely continue to do so. In past periods, the state has expected the universities to tighten freshman admission policies when they were found to be drawing from beyond these pools. When the universities tighten their admission policies, they effectively redirect a portion of their lower‑division enrollment to the community colleges.

A New Dual Admission Pathway and Other New Expectations Also Could Affect University Enrollment. Another factor the Legislature may wish to consider is the potential impact of the new expectations that the Governor proposes linking to the university base increases in 2021‑22. In particular, we think the Governor’s proposed dual admission pathway potentially could reduce lower‑division enrollment at the universities by encouraging more students to begin their studies at the community colleges. The Governor’s equity and online education expectations also could have some impact on enrollment levels. For example, student success initiatives that improve persistence rates and encourage more students to study full time would contribute to enrollment increases.

Recommendations

Set Enrollment Target for 2022‑23. We recommend the Legislature set enrollment expectations for the universities for the 2022‑23 academic year. Given the various countervailing factors cited above, as well as the state’s limited capacity to support new ongoing spending, the Legislature could set an expectation that the universities hold enrollment flat in 2022‑23. If the Legislature wished to support enrollment growth, we estimate the General Fund cost of every 1 percent growth in resident enrollment would be $34 million at CSU and $24 million at UC. (These estimates are based on the traditional marginal‑cost formula.)

Student Support

In this section, we focus on student support programs, with a particular emphasis on food, housing, mental health, and technology programs, as well as emergency grants. The Governor has five proposals in this area, together totaling $90 million ($45 million ongoing and $45 million one time). Three of the proposals involve CSU and two involve UC. After providing background on student support programs, we describe each of the proposals in this area, then assess those proposals, and make associated recommendations.

Background

Many Students Report Difficulty Covering Basic Needs. The term “basic needs” generally refers to living costs that affect students’ well‑being. Definitions vary, but they almost always include food and housing and may also include other components, such as mental health and technology. Previous surveys suggest a notable share of university students have difficulty covering certain basic needs. In particular, in surveys conducted before the pandemic, 42 percent of CSU undergraduates and 47 percent of UC undergraduates reported very low or low food security. (As these surveys have low response rates, respondents might not be representative of all students.)

Traditional Financial Aid Programs Provide Support for Basic Needs. The primary way the federal government, the state, and universities support living costs during the college years is through financial aid. Many students with financial need qualify for a federal Pell Grant (worth up to $6,345 annually) and a state Cal Grant access award (worth up to $1,648 annually for most students). Federally subsidized and unsubsidized loan programs also are available to assist students. These grants and loans can be used for any cost of attendance, including housing, food, transportation, and books and supplies. In addition to federal and state programs, UC has its own institutional aid program funded using a portion of student tuition and fee revenue. The university indicates this program covers all costs of attendance for students with financial need, after assuming a self‑help expectation ($10,500) that can be met through any combination of work and borrowing. (Although CSU also has an institutional aid program, its funds are sufficient only to provide tuition coverage, without additional aid available for living costs.)

Targeted Programs Also Support Basic Needs. In addition to traditional aid programs, many campuses provide programs targeted toward basic needs. These programs include on‑campus food pantries, emergency housing, and health services (including mental health services), among others. These targeted programs are funded through a mix of sources, including state funds, philanthropy, and, in some cases, student fees. As Figure 9 shows, the state has funded several basic needs initiatives in recent years. Some of these initiatives expanded existing on‑campus efforts whereas others created new programs. Some initiatives also sought to better connect students with off‑campus public assistance programs, such as the CalFresh food assistance program. Prior to 2019‑20, state initiatives were supported with one‑time funds. In 2019‑20, the state provided ongoing funding for several initiatives, totaling $6.5 million ongoing General Fund at CSU and $23.8 million ongoing General Fund at UC. (The difference in ongoing funding levels primarily reflected differences in the segments’ requests that year.)

Figure 9

State Has Funded Several Basic Needs Initiatives

General Fund, Unless Otherwise Noted (In Millions)

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

|

|

CSU |

||||

|

Food and housing |

$2.5 |

$1.5 |

$15.0 |

— |

|

Rapid rehousing |

— |

— |

6.5 |

$6.5 |

|

Mental health services |

— |

— |

3.0a |

— |

|

Totals |

$2.5 |

$1.5 |

$24.5 |

$6.5 |

|

UC |

||||

|

Food and housing |

$2.5 |

$1.5 |

$15.0 |

$15.0 |

|

Rapid rehousing |

— |

— |

3.5 |

3.5 |

|

Mental health services |

— |

— |

5.3 |

5.3 |

|

Totals |

$2.5 |

$1.5 |

$23.8 |

$23.8 |

|

aReflects one‑time Mental Health Services Fund. |

||||

During Pandemic, Some Students Likely Are Having More Challenges With Basic Needs. The state does not have comprehensive data on the impact of the pandemic on student financial need, largely because financial aid applications use income data from two years prior to the award year. However, surveys suggest many students had unanticipated financial needs due to the pandemic. In a California Student Aid Commission survey of financial aid applicants across all segments conducted in late spring 2020, over 70 percent of respondents reported experiencing a loss of income due to the pandemic. Students also reported increased concern about paying for various living costs, including housing and food, health care, and technology. (This survey had a response rate of 12 percent.)

Relief Funds Have Provided Emergency Grants to Students. The universities received a first round of federal relief funds in spring 2020, and they are scheduled to receive a second round in the coming weeks. (We provide further detail on both rounds of funding in our recent post, Second Round of Federal Higher Education Relief Funds.) Campuses must spend a portion of these funds for student aid. Across the two rounds, the minimum portion for student aid totals $525 million at CSU and $260 million at UC. Under the new federal legislation (relating to second‑round funding), grants may support students’ regular costs of attendance or emergency expenses related to COVID‑19. The new legislation includes a requirement for institutions to prioritize aid for students with exceptional need, such as Pell Grant recipients. In addition to the federal relief funds, the state provided funds in the 2020‑21 Budget Act for emergency grants to undocumented students (who were generally excluded from receiving aid under the first round of federal relief), allocating $3 million for CSU and $1 million for UC. The universities have also directed some institutional funds, including from philanthropy, to provide emergency student aid.

Proposals

Governor Proposes Ongoing Funds for Mental Health and Technology at CSU and UC. The Governor proposes to provide CSU and UC each with $15 million ongoing General Fund for student mental health services and access to technology (electronic devices and internet connectivity). The provisional language does not specify what portion of funds are to be used in each of the two areas, with the universities having discretion to determine the split. CSU and UC would be required to report by March 1 annually how the funds were distributed to campuses and spent.

Governor Proposes Ongoing Funds for CSU Basic Needs Initiative. This proposal would provide $15 million ongoing General Fund to sustain and expand this existing program. This program is part of the Graduation Initiative 2025, a systemwide effort to increase graduation rates and close achievement gaps. According to CSU, the Basic Needs Initiative supports a broad range of activities, including food pantries, emergency housing, emergency grants, and (since the start of the pandemic) the distribution of laptops and mobile hotspots. As under the mental health and technology proposal, CSU would be required to report by March 1 annually how the funds were distributed to campuses and spent. (This proposal does not apply to UC, which received $15 million ongoing for a similar purpose in 2019‑20. UC has a comparable, existing annual reporting requirement for these funds.)

Governor Proposes One‑Time Funds for Emergency Grants at CSU and UC. The Governor proposes to provide $30 million to CSU and $15 million to UC. The provisional language specifies that each segment would allocate the funds to campuses based on their headcount of Pell Grant recipients, as well as undocumented students qualifying for resident tuition. Campuses may award grants to students who self‑certify that they meet the following criteria:

- Have an emergency financial need.

- Meet the financial eligibility requirements to receive a Pell Grant or (for undocumented students) a Cal Grant.

- Are currently enrolled full time with a grade point average of at least 2.0 in one term during the past academic year or meet certain full‑time employment conditions.

Assessment

Proposals Address a Longstanding Problem Exacerbated by the Pandemic. Despite the lack of comprehensive data measuring students’ unmet needs relating to food, housing, mental health, and other concerns, the available survey data suggests that unmet needs are substantial. Moreover, these needs have likely increased for some students during the pandemic. The Governor’s proposals address this sizable and timely problem.

To Date, State Has Taken a Piecemeal Approach to Addressing Basic Needs. Over the past four years, the state has funded multiple basic needs initiatives at the universities. However, the state’s overarching strategy for addressing students’ root problems remains unclear. The state lacks both a definition of student basic needs and a way of measuring demand for programs supporting them. In the absence of this information, funding levels for basic needs initiatives tend to reflect budget expediency (balancing available funding with the segments’ requests), without a strong guiding policy rationale. Moreover, the state’s approach to allocating funds between segments and among campuses is inconsistent and has not directly tied funding to need. For example, sometimes UC and CSU receive the same funding level for a given initiative, and other times CSU receives a higher funding level to reflect its higher enrollment. The segments, in turn, sometimes allocate funds to campuses evenly, sometimes in proportion to enrollment or other measures of student demand, and sometimes through competitive grants.

Governor’s Proposals Would Add to This Uncoordinated Approach. The Governor proposes to create a new mental health and technology program on top of the existing basic needs programs. That new program combines two distinct objectives—increasing student mental health resources and increasing digital equity—without a clear nexus between the two. At CSU, the proposed program’s objectives would overlap with those of the separately funded Basic Needs Initiative. Moreover, it is unclear how the new funds are intended to interact with existing ongoing programs (such as the rapid rehousing program) or proposed one‑time initiatives (such as the emergency grants).

Opportunity Exists to Coordinate State and Federal Relief Funding. The administration did not have the benefit of knowing about the new federal relief package when developing its budget proposals, as the federal legislation was not enacted until late December 2020. Now that substantial new federal funds have been allocated for student aid, the Legislature can consider what state funding, if any, it would like to add in this area. Unfortunately, as with many other groups impacted by the pandemic, there is no comprehensive data measuring the increase in students’ financial need under COVID‑19, or the amount of unmet need remaining after accounting for traditional and emergency financial aid programs. As a result, the Legislature has no easy way to determine if additional state funds are warranted.

Opportunities Remain to Leverage Public Assistance Programs. Over the past several years, the state has worked to increase student enrollment in CalFresh. Nonetheless, a recent report from the California Department of Social Services estimates that between 290,000 and 560,000 students eligible for CalFresh across California’s public segments (including the community colleges) were not enrolled as of 2018‑19. The state has an opportunity to further increase CalFresh enrollment in 2020‑21 and 2021‑22 as a result of the new federal relief legislation. That legislation expands student CalFresh eligibility during the COVID‑19 emergency by removing the standard work requirement for certain students who are very low‑income or eligible for work‑study. Moreover, the state has opportunities to translate the lessons learned from its CalFresh student enrollment efforts to various other public assistance programs (such as Medi‑Cal, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and unemployment insurance) that students may be underutilizing.

Recommendations

Clarify Objectives of Proposals Before Approving Ongoing Funds. If the Legislature wishes to provide additional ongoing funding for basic needs, we recommend clarifying the scope of each proposal and how it would relate to existing financial aid and basic needs programs. In cases where multiple programs serve similar objectives (such as CSU’s Basic Needs Initiative and the existing rapid rehousing program), the Legislature could consider consolidating the programs to make them easier for students to navigate and universities to administer. In cases where one program serves notably different objectives (such as mental health and technology), the Legislature could consider separating it into two programs.

Modify Emergency Grants Proposal to Reflect New Federal Relief. We recommend the Legislature direct CSU and UC during hearings to report on how campuses plan to distribute the upcoming federal relief funds for student aid. After obtaining this information, the Legislature will be in a better position to target the proposed state emergency aid funds. If some students are excluded from the new round of federal relief (as undocumented students were under the first round), the Legislature could target state funds to support those students. Alternately, the Legislature could design state aid to supplement federal aid, such as by providing summer‑term assistance to students who would receive federal aid in the spring. If the Legislature provides additional funds for emergency student aid in 2021‑22, we recommend requiring the segments to report on how they distribute and use the additional funding, as this could help guide future state budget decisions. The state required similar reports for the emergency aid it provided to undocumented students in 2020‑21.

Expand Efforts to Increase Student Utilization of Public Assistance Programs. While the segments’ existing basic needs programs provide CalFresh enrollment assistance, there are likely opportunities to expand student enrollment in other public assistance programs, which could help students cover other costs, including housing, mental health, and technology costs. The Legislature could direct the segments to partner with the relevant state and local agencies to explore strategies to increase utilization of other public assistance among college students.

Consider Developing Coordinated Strategy to Meet Students’ Basic Needs. Beyond its immediate budget decisions in 2021‑22, the Legislature has an opportunity to begin shaping the state’s longer‑term strategy around students’ basic needs. To move away from the current piecemeal approach, the state would need to establish overarching objectives, concretely define students’ basic needs, measure the amount of need in the state, align state funding levels and allocations to that need, identify ways to track progress over time, and coordinate with traditional student financial aid programs as well as other public assistance programs. Developing this more holistic strategy would take time, and it would require coordination among the segments and other stakeholders, but the Legislature might begin considering what first steps it might wish to take toward these ends. We encourage the Legislature to ensure that any holistic strategy around students’ basic needs also take into account the state’s broader fiscal situation, which at this time is made more challenging by projected out‑year operating deficits.

Faculty Professional Development

In this section, we focus on faculty professional development, particularly around online instruction. We first provide background on the issue, then describe the Governor’s proposals to provide one‑time funding for additional online‑focused faculty professional development. Next, we assess the proposals and offer associated recommendations.

Background

CSU and UC Routinely Provide Faculty Professional Development. Common types of faculty professional development include workshops, conferences, consultations, and online resources on topics such as course design, pedagogy, and student support. At both segments, these activities are commonly delivered by the campuses’ centers for teaching and learning, as well as in other settings. Campuses support faculty professional development through a mix of fund sources, including core funds, federal funds, and private grants.

More Faculty Have Been Participating in Professional Development During Pandemic. Since the onset of the pandemic, both segments have offered professional development to support faculty with the rapid transition to online instruction. At UC, centers for teaching and learning served 6,700 faculty in 2019‑20—more than twice as many as in the previous year. At CSU, about 60 percent of faculty participated in professional development focused on online instruction in summer 2020. CSU indicates this was much higher participation than normal for summer professional development programs. During the pandemic, federal relief funds have been available to support these types of activities. Based on institutional reporting, at least 13 CSU campuses and 2 UC campuses had used some funds from the first round for faculty or staff training in online instruction as of December 31, 2020.

State Has Funded Various Initiatives Intended to Improve Online Instruction. As mentioned earlier in this report, the state provided $10 million ongoing General Fund support in 2013‑14 to CSU and UC each to expand online education. CSU has used the funds to create incentives for faculty to offer fully online courses in subjects with high enrollment demand. UC has used the funds for the Innovative Learning Technology Initiative, which provides grants for faculty to develop online and hybrid courses that students at any campus may access. In 2019‑20, the state also provided the Office of Planning and Research with $10 million ongoing for the California Education Learning Laboratory, an intersegmental program that similarly aims to expand online and hybrid course offerings. In addition to these programs, the state has supported multiple one‑time initiatives at the segments to develop and expand the use of open educational resources in online courses.

Proposal

Governor Proposes One‑Time Augmentation for Faculty Professional Development Focused on Online Education. The Governor proposes one‑time General Fund augmentations of $10 million at CSU and $5 million at UC for faculty professional development related to online education. The administration indicates the proposal is intended to support faculty as they continue to adapt to teaching online during the pandemic. The provisional language specifies that the funds are to support “culturally competent professional development,” which the administration suggests would mean integrating principles of equity into the program. Based on conversations with the administration, the proposed amount reflects available resources in the Governor’s budget, as well as the relative number of faculty at each segment.

Assessment

Governor Has Identified Important Area of Focus. At CSU and UC, faculty entered the pandemic with varying levels of experience teaching online. Providing additional support to faculty potentially could increase their confidence and satisfaction while improving the quality of online instruction and raising student course completion rates. In addition, the proposed emphasis on cultural competence could help reduce equity gaps in online course completion. These objectives are important, particularly if the state were to pursue a long‑term strategy of sustaining higher levels of online education beyond the pandemic, as the Governor has proposed. (We discuss the Governor’s online education proposal in our “Base Support” section.)

Further Needs Assessment Is Important to Obtain. The administration has not undertaken a full assessment of the need for additional professional development in this area. Lacking such an assessment, some key information remains unknown. Most notably, it is unknown how many faculty at CSU and UC need additional support with online instruction, what types of support they would benefit from, and the cost of providing that support. The administration also seems to miss an opportunity to draw upon lessons learned from recent professional development activities. These lessons learned could be pivotal in designing future initiatives in this area.

Forthcoming Federal Relief Funds Could Support Additional Professional Development. In addition to the remaining funds provided under the first round, CSU and UC are expected to receive $592 million and $261 million, respectively, in institutional relief under the second round of federal funds. These federal funds are better timed to support immediate faculty professional development needs under COVID‑19 than the Governor’s proposed funds. The Governor’s proposed funds would reach campuses no sooner than July 2021—more than a year after the shift to online instruction, and within months of when both CSU and UC intend to resume primarily in‑person instruction.

Recommendation

Reconsider Proposal After Receiving Online Education Report. We recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal to provide additional funding for faculty professional development in 2021‑22, as federal relief funds and other institutional funds are available to address the immediate needs faculty have for improving online instruction. Though we recommend not providing a state augmentation at this time, the Legislature could revisit this issue upon learning more about unmet faculty professional development needs. Specifically, the Legislature could direct the segments to include an assessment of the need for additional faculty support as part of the online education reports we recommended developing earlier in the “Base Support” section. More information about faculty professional development needs could allow the Legislature to determine whether a one‑time augmentation might be warranted in the future or existing ongoing professional development funding might be sufficient.

Deferred Maintenance

In this section, we focus on deferred maintenance issues at the universities. We first provide background on deferred maintenance backlogs, then describe the Governor’s proposals to fund deferred maintenance projects at CSU and UC. Next, we assess the proposals and offer associated recommendations.

Background

Campuses Have Sizable Maintenance Backlogs. Like most state agencies, CSU and UC campuses are responsible for funding the maintenance and operations of their buildings from their support budgets. When campuses do not set aside enough funding from their support budgets to maintain their facilities or when they defer projects, they begin accumulating backlogs. These backlogs can build up over time, especially during recessions when campuses sometimes defer maintenance projects as a way to help them cope with state funding reductions. Both universities report having large backlogs. CSU estimates its backlog totals $4 billion across all of its campuses. UC has not shared a precise estimate, but staff at the UC Office of the President report the total backlog is more than $8 billion.

State Has Provided Funds to Address Backlogs. In the years following the Great Recession, the state provided one‑time funding to help the universities address their maintenance backlogs. Figure 10 shows the amounts appropriated by the state each year from 2015‑16 through 2020‑21. Funding over the period totaled $678 million.

Figure 10

State Has Provided Funding to

Address Deferred Maintenance at the Universities

General Fund, Unless Otherwise Noted (In Millions)

|

2015‑16 |

2016‑17 |

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

|

|

CSU |

$25 |

$35 |

— |

$35 |

$239a |

— |

|

UC |

25 |

35 |

— |

70b |

179a,b |

$35b |

|

Totals |

$50 |

$70 |

— |

$105 |

$418 |

$35 |

|

aThe 2020‑21 budget package allowed CSU and UC to repurpose unspent 2019‑20 deferred maintenance funds for other operational purposes. bIn each of these years, $35 million came from state‑approved university bond funds. |

||||||

Universities Are Developing Long‑Term Plans to Address Backlogs. To help guide future state funding decisions, the Legislature in the Supplemental Report of the 2019‑20 Budget Act directed the universities to develop long‑term plans to quantify and address their maintenance backlogs. In January 2021, CSU submitted its maintenance plan to the Legislature. In the plan, CSU estimates it would need to spend $308 million annually to adequately fund maintenance and prevent its backlog from growing. This is $126 million more than it currently spends annually on maintenance ($182 million). To eliminate its existing $4 billion backlog, CSU estimates it would have to spend an additional $402 million each year over the next ten years. UC has not yet submitted its maintenance plan to the Legislature. According to staff at the UC Office of the President, the report will be submitted sometime between March and July of this year.

Proposals

Governor Proposes Addressing Deferred Maintenance at the Universities. The Governor proposes to provide CSU and UC each $175 million in one‑time General Fund support for this purpose. Specifically, CSU could use the funds for deferred maintenance projects, whereas UC could use the funds either for deferred maintenance or energy efficiency projects. The administration indicates that the dual purposes of the funding for UC stemmed from UC’s request to pursue energy efficiency projects.

Proposed Projects Are Forthcoming. Both universities submitted to our office long lists of projects they potentially could support with the proposed funding. Both lists contain projects with costs totaling in excess of the amount proposed by the Governor, with CSU’s list of projects totaling $741 million and UC’s list totaling $250 million. The universities are revisiting their lists to determine which projects they would undertake within the proposed funding level. Under the administration’s proposal, CSU’s and UC’s final project lists would be authorized by DOF after enactment of the budget. Budget bill language would direct the administration to report to the Legislature on which projects were funded within 30 days after the funds are released to the universities.

Assessment

Deferred Maintenance Is a Prudent Use of One‑Time Funding. In The 2021‑22 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook, we advised the Legislature to direct any immediate surplus funding toward one‑time actions that either strengthen the state’s budget resiliency or help address the extraordinary public health and economic impacts of the pandemic. Addressing deferred maintenance could be viewed as strengthening the state’s budget resiliency in that it pays for largely unavoidable costs that will grow if not addressed. Funding projects that help reduce UC’s utility costs over time also could be beneficial, though these projects could be lower priority than those deferred maintenance projects that would have significant cost escalation were they to be left unaddressed.

Proposed Project Authorization Time Line Is Problematic. While we think the administration’s focus on addressing deferred maintenance is reasonable, we are concerned with the administration’s proposal to notify the Legislature of the approved projects after the funds are released. Such an approach would give the Legislature no ability to review the list of projects and ensure the projects are consistent with intended objectives and legislative priorities.

Recommendations