LAO Contacts

November 10, 2020

An Analysis of University Cash Management Issues

During recessions, agencies can experience challenges when their cash cushions shrink. While the state’s two public university systems—the California State University (CSU) and the University of California (UC)—have historically not experienced cash challenges, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and subsequent recession have created new cash issues for them. In this post, we analyze cash management issues at CSU and UC. We first compare cash flow of the state and the universities, then examine how the state and universities invest their cash, and next summarize how the universities helped the state with its cash management during the Great Recession. We conclude by identifying cash issues that have arisen during the COVID-19 pandemic and discussing related issues for legislative consideration.

Cash Flow

State Routinely Manages Its Cash Position Through Short-Term Borrowing. As we noted in our publication Managing California's Cash, the state’s expenses are relatively even each month, but the state receives most of its revenues in the latter half of the fiscal year. As a result of this misalignment, the state routinely has to monitor and manage its cash position. When revenues received to date are too low to cover costs incurred to date (that is, its cash position is negative), the state typically engages in short-term borrowing—first internally from its available accounts, then externally from the municipal market. The state must repay most of this borrowing with interest, but some internal borrowing is interest-free. Though internal and external borrowing is routine in most fiscal years, the state has other cash management tools it can use in extraordinary situations. For example, during the Great Recession, the state paid workers late.

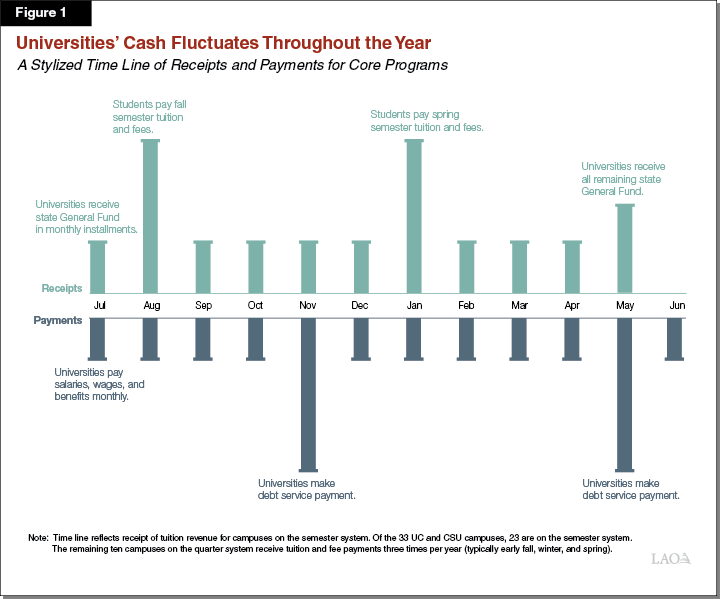

Universities’ Academic Programs Are Typically in a Better Cash Position Than the State. In contrast to the state, the universities receive their core revenues—primarily state General Fund and tuition revenue—in advance of their costs. Campuses receive tuition revenue at the start of each term and state General Fund on a monthly basis (Figure 1). Their operating expenses are spread about evenly throughout the year, with the exception of debt service payments, which are made twice a year—in the fall and spring. Because of the timing of these inflows and outflows, campuses typically maintain positive cash positions and do not need to borrow internally or externally to manage their cash flow throughout the year.

Universities Also Do Not Face Timing Issues With Noncore Programs. In addition to their core-funded academic activities, campuses operate numerous self-supporting enterprises, such as student housing, dining, bookstores, and (in the case of UC) medical centers. Cash flow statements for these programs are not publicly available. Staff at the CSU Chancellor’s Office and UC Office of the President, however, note that these programs also do not normally face cash timing issues, such that they maintain positive cash positions and do not routinely borrow for cash flow purposes.

Investing Cash

State Pools Cash in Short-Term Investment Account. Rather than let cash sit idly, the state invests its cash surpluses. The state pools cash from the General Fund, special funds, funds from participating local entities, and other funds into a single investment account (the Pooled Money Investment Account, or PMIA). The returns in this investment account are available as investment income to most of the contributing fund sources. Under state law, money in this account is invested in relatively low-risk, short-term assets, such as U.S. Government securities and domestic corporate bonds. The goals of the account are to safeguard taxpayer money, ensure cash is readily available when program costs are incurred, and earn a modest rate of return.

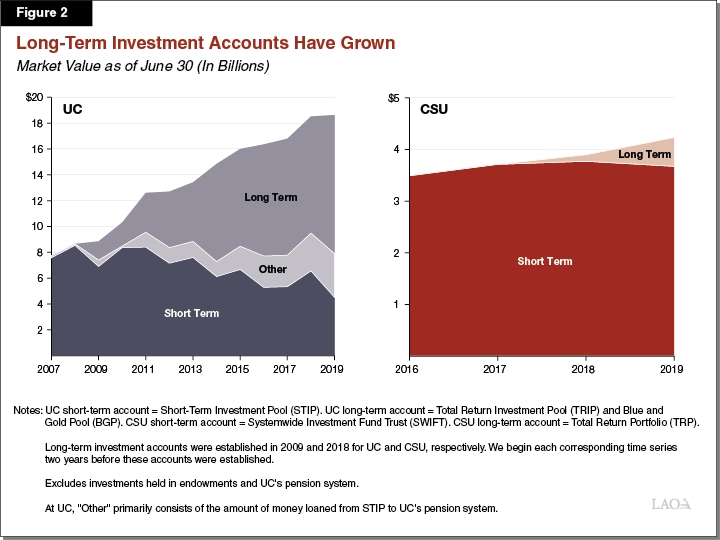

Universities Manage Both Short- and Long-Term Investment Accounts. Historically, the universities pursued an investment strategy similar to the state by pooling together their cash across all campuses and investing it in short-term accounts. Like the state, cash held in the universities’ short-term accounts is placed into low-risk investments, such as U.S. Government securities and domestic corporate bonds. More recently, the universities have added long-term investment accounts. Investments in these accounts tend to be higher risk, with some funds held in the stock market. (Whereas the universities do not hold stocks in their short-term accounts, 47 percent of CSU’s long-term account and 36 percent of UC’s long-term accounts were invested in stocks as of the end of June 2019.) The universities’ long-term accounts tend to earn higher returns than their short-term investments, but funds in these accounts cannot be liquidated (converted into cash) as quickly. UC and CSU began shifting funds from their short-term accounts into their long-term accounts in 2009 and 2018, respectively, with the amount in their long-term accounts growing through 2019 (Figure 2).

UC Has Been Borrowing to Make Pension Contributions. In addition to shifting funds into its long-term investment account, UC has borrowed funds internally from its short-term investment account and externally using bonds to help make its annual pension contributions. Specifically, since 2010, UC has borrowed $3.2 billion internally and $937 million externally for this purpose. (The Board of Regents has authorized the Office of the President to borrow an additional $1.8 billion through 2021‑22 for its pension costs using either internal or external sources.) Campuses and the Office of the President are repaying this pension borrowing with interest over time using their operating budgets. The investment returns resulting from this borrowing help UC pay down its unfunded pension liability. The borrowing, however, results in UC having less cash it can liquidate in the near term to address any immediate fiscal issues it might face.

Cash Management During the Great Recession

Universities Had Relatively Larger Cash Cushions Than State During Great Recession. As we noted in our publication The Great Recession and California’s Recovery, the state faced cash challenges during the Great Recession. During this period, the state’s cash cushion notably declined, impacting its ability to borrow internally. By comparison, the universities had relatively larger cash cushions, bolstered by the condition of campuses’ noncore programs, which did not experience notable revenue losses. Because of the universities’ relatively larger cash cushions, they became part of the state’s multipronged effort to weather its cash challenges. As explained in the next three paragraphs, the state took three actions involving the universities to help manage its cash position during the Great Recession.

State Delayed General Fund Disbursements to CSU and UC. During the Great Recession, the state delayed some General Fund payments to the universities. When state funding was delayed, the universities had to find ways to continue supporting their core expenses. In some cases, the universities had to cover costs from within their own budgets. For example, between April and July 2009, the state did not give CSU its regular disbursements to cover payroll costs, instead requiring CSU to pay those costs out of its own budget. In other cases, the state was able to substitute General Fund payments with other fund sources. For example, in the first few months of the 2009‑10 fiscal year, the state delayed General Fund payments to the universities but provided $1.6 billion in federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act relief funds to help the universities cover their costs during those months.

State Required CSU to Temporarily Keep Cash in State Account. In 2010‑11, the state required CSU to keep a portion of its cash in the state’s short-term account rather than CSU’s investment accounts. The action was intended to give the state an additional cash cushion before going to the municipal market for external borrowing. The amount that CSU was required to keep in the state’s account varied between $300 million and $870 million throughout 2010‑11. At the start of 2011‑12, the funds were to shifted to CSU’s short-term investment account. (The state did not take any similar actions involving UC.)

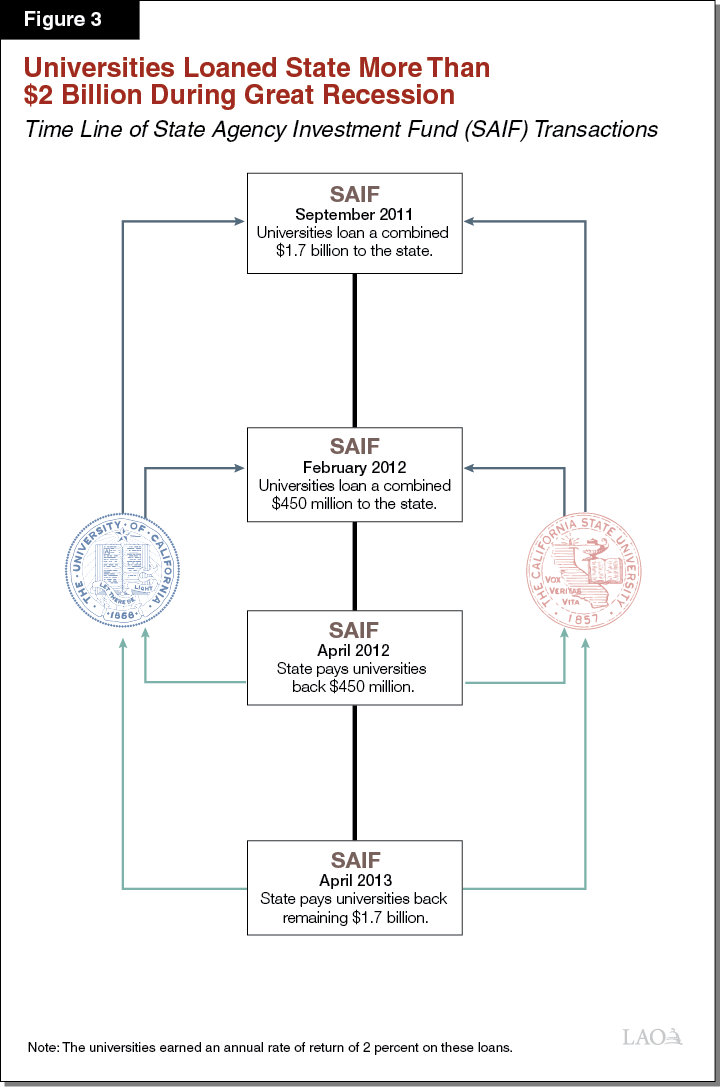

State Borrowed Cash From Universities. In 2011, the state developed a new account—the State Agency Investment Fund (SAIF)—and made arrangements with CSU and UC for them to make deposits into it. The universities deposited over $2 billion into the account (Figure 3). The state eventually repaid the segments with interest. The arrangement was designed to benefit both the state and universities—the state increased its cash cushion, whereas the universities received a higher return than if the funds were kept in their own short-term accounts.

Cash Management During the Pandemic

State’s and Universities’ Cash Positions Are Somewhat Reversed. As we noted in our recent publication, An Update on California's Cash Management Situation, the state’s cash cushion is larger than it has been in previous recessions. This larger cushion is primarily due to the state’s higher General Fund and special fund reserves, which increase its capacity to borrow internally. Given the state’s larger cash cushion, it is less likely to need to take many of the extraordinary actions it took during the previous recession. By contrast, the universities have lost a significant amount of noncore revenue resulting from campus closures, which is, in turn, is reducing their cash cushions. The next three paragraphs describe new actions the universities are taking or considering to help them weather their emerging cash challenges.

Campuses Indicate They Might Begin Relying on Internal Borrowing. One tool available to campuses to address their negative cash positions is to internally borrow among their accounts. State law explicitly authorizes CSU to borrow funds from one of its accounts for another account, so long as the funds are (1) returned to the original account by the time needed for expenditure and (2) repaid with interest. UC also has the authority to borrow funds among its accounts. While campuses have not traditionally undertaken internal borrowing for operations, staff at the universities have signaled to the Legislature that they might use internal borrowing and transfers moving forward. Talk of such actions emerged earlier this year when the 2020‑21 May Revision contained a proposal that would have given campuses more flexibility to transfer funds between accounts without repaying the funds or incurring interest. (This proposal was not adopted in the final 2020‑21 budget package.)

Universities Are Adjusting Investment Strategies. In 2019‑20, UC nearly doubled the amount of cash it held in its short-term account (increasing the total amount to $10.5 billion). The increase in the account was due to the university transferring funds out of its long-term accounts, including by liquidating the smaller of its two long-term accounts. While CSU has not yet reduced the amount held in its long-term account, staff at the Chancellor’s Office indicate that the university does not plan to transfer any more cash from its short-term account into its long-term account at this time. These UC and CSU decisions will provide campuses with larger cash cushions that can be readily accessed during the pandemic.

UC Recently Issued Bonds to Support Its Operations. In July 2020, UC issued $1.5 billion in “working capital” bonds, which provide cash for UC’s operations. Based on discussions with the Office of the President and campuses, campuses likely will use the borrowed funds primarily to help sustain their noncore programs throughout 2020‑21. Campuses will repay the bonds from their operating budgets over ten years. For the first five years, UC will only make interest payments, thereby delaying the largest debt service costs to later years. According to the Office of the President, the Board of Regents approved the working capital bonds because of the low cost of borrowing. UC staff also emphasized that the borrowing was intended to be a one-time action, with the Board of Regents unlikely to authorize additional working capital bonds. CSU has not issued any working capital bonds to date.

Issues to Consider

Universities Have Greater Fiscal Flexibility Than the State. The California Constitution imposes several restrictions on the state in an effort to safeguard taxpayer money. For example, the state is forbidden from investing in the stock market (except in a few cases, most notably for pensions), thereby limiting the state to relatively safe, short-term investments. The state also must balance its budget each year and is prohibited from issuing bonds to cover operating deficits. By contrast, the universities have significantly greater flexibility than the state. Notably, both universities may invest funds in the stock market, and UC may issue working capital bonds. Although this greater flexibility allows the universities potentially to earn higher rates of return and gain better access to cash, it also exposes them (and indirectly the state, students, and other stakeholders) to greater risk.

University Strategies Come With Trade-Offs. The unprecedented challenges that the COVID-19 pandemic has created for the universities underlies their recent consideration of extraordinary cash management strategies. Each of the cash management strategies that the universities have recently implemented or are considering comes with trade-offs. Below, we summarize the trade-offs for three specific fiscal strategies that have been or are being considered.

Internal Transfers. Internally transferring funds from one account to another (such as using reserves of student extended education fees to sustain parking programs) would enable campuses to fund their most urgent costs and priorities—potentially helping to keep noncore programs afloat during this time—but would result in funds not being spent on their originally intended purpose.

Investment Changes. Reducing the amount held in long-term investment accounts provides campuses with a larger cash cushion to cover immediate costs and reduces the universities’ risk of investment losses. It also, however, likely results in less investment earnings over the long run, thereby reducing the amount available to help the universities cover future costs.

Working Capital Bonds. While UC’s working capital bonds come with relatively low interest, repaying the debt could be challenging if the pandemic and economic downturn last longer than expected. These challenges could be especially heightened five years from now, when UC’s debt service payments are scheduled to notably increase.

Universities’ Fiscal Condition Will Be Important to Watch Over Coming Years. Given the significant effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the universities’ budgets, together with the new strategies they are considering in response, we recommend the Legislature closely monitor the universities’ fiscal health over the next several years. Specifically, through oversight hearings or reporting requirements, we recommend the Legislature direct the universities to provide regular updates on their cash cushions, including how much cash they have in their short- and long-term accounts, the amounts of any internal loans or transfers that campuses have made to sustain their core or noncore programs, and any new external borrowing they undertake for cash or operating purposes.