LAO Contact

August 31, 2020

An Update on California's Cash Management Situation

In the annual budget process, the Legislature creates a plan that aligns General Fund expenditures with anticipated revenues for the upcoming fiscal year. After this budget plan is put into law, the executive branch has the responsibility to execute it. Importantly, this means managing the General Fund’s cash—for example by collecting tax revenues and paying the state’s bills.

Cash management is not, therefore, an issue that typically requires sustained legislative attention. However, when a recession occurs, the state’s cash position typically weakens. In past recessions, the Legislature has had to take steps to address the state’s cash position to ensure California was able to pay its bills. Our office monitors the state’s cash position in order to anticipate these potential challenges for the Legislature in advance.

In this post, we give an update on the General Fund’s current cash situation. In particular, although there was a great deal of concern about cash in the spring of 2020, we explain why the situation did not significantly deteriorate as expected. We also discuss the General Fund’s “cash outlook” for the rest of the fiscal year, including major developments that are likely to affect the state’s cash situation for better or worse.

Understanding Cash Management

What Is Cash Management?

State Budget and Cash Situations Are Different. The budgetary situation of the General Fund, which is the primary fiscal focus of the Legislature each year, is different than its cash situation. Each year, the Legislature passes a budget, which is a plan for how much the state will pay in expenditures and receive in revenues over the course of the next fiscal year. In addition, the state must plan when these expenditures and revenues will occur. The timing of these—expenditure disbursements and revenue receipts—comprise the state’s cash position. In this report, we described the state’s cash management practices in much more detail.

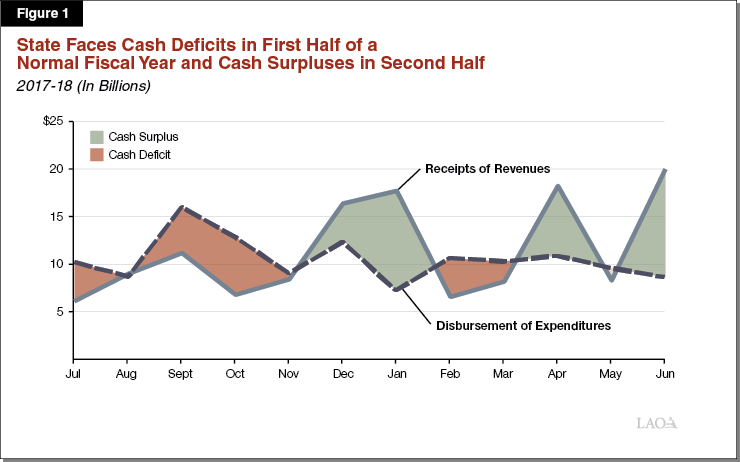

State Faces Cash Surpluses and Deficits Throughout the Fiscal Year. Cash deficits and surpluses arise due to the unequal distribution of disbursements and receipts throughout the fiscal year. The state disburses money fairly evenly throughout the fiscal year. For example, the state typically transfers funds to school and community college districts, makes payments to Medi-Cal providers, and issues payroll to state employees every month of the year. However, the state receives most of its revenues in the latter half of the fiscal year, in particular January, April, and June, which are key months for collections of the personal income tax. As a result, early in the fiscal year the state tends to be disbursing more than it is receiving (and has a cash deficit) and later in the year tends to be receiving more in than it is disbursing (and therefore has a cash surplus). Figure 1 shows the state’s cash deficits and surpluses in a normal fiscal year.

State Controller Uses a Variety of Techniques to Manage Cash Position. The General Fund’s daily cash situation is monitored and managed by the State Controller’s Office (SCO). (The daily cash situations of other state funds, like special funds, are primarily managed by state departments.) SCO is led by the State Controller, who has broad constitutional and statutory powers to use a variety of techniques to address cash flow deficits. For example, the Controller borrows from internal sources, namely state funds other than the General Fund. The Controller also can authorize external borrowing, for example by issuing Revenue Anticipation Notes (RANs), which are cash flow borrowing instruments that rely on the municipal bond market. These are both routine, ordinary tools that have been used by the state for decades. However, the Controller also can take more extraordinary actions when cash deficits become more severe. This includes, for example, delaying payments or issuing IOUs.

Important Terms in This Post. Throughout this post we will use two terms that both are measures of the health of the state’s cash situation. They are:

General Fund Cash Position. The General Fund cash position is measured at a point in time (usually on a single day or at the end of the month). If the General Fund cash position is negative it means the state is facing a cash deficit and must borrow from internal or external sources to pay its bills.

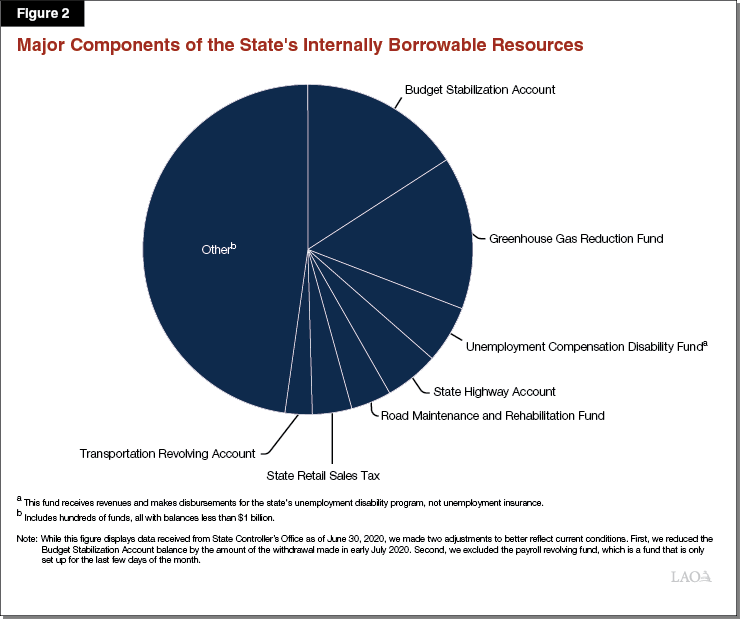

Available Cash Cushion. The available cash cushion is the amount of unused internal and external borrowable resources available to the Controller at any point in time. The more resources available, the less likely the state’s cash deficits will mean that the Controller needs to take more extraordinary actions to manage the state’s cash situation (for example, delaying payments). The cash cushion is made up of hundreds of different funds. Figure 2 shows the major components of the state’s roughly $52 billion internal borrowable resources available as of July 31, 2020.

Cash Management in 2019-20

Earlier this spring many observers, including our office, worried that the state’s cash situation was going to deteriorate rapidly. In particular, in a letter to the Legislature on April 10, the Department of Finance (DOF) reported that the Controller was projecting that the delay in deadlines for tax filing (from April to July) was going to result in a substantial decline in the state’s cash cushion. In particular, the April letter projected the cash cushion could diminish to roughly $9 billion by the end of the fiscal year. In response, the Governor authorized the Controller to open the General Cash Revolving Fund, which allows the state to issue Revenue Anticipation Warrants—a form of cash borrowing that is relatively unusual and typically only required when the state is facing more substantial cash deficits.

As it turned out, however, the state’s cash situation remained strong through the end of 2019-20. On the last day of the fiscal year, the state’s cash cushion stood at $37.3 billion, much higher than the April letter suggested. In the remainder of this section, we discuss the reasons the state’s cash situation remained relatively strong in 2019-20, despite the stresses placed upon it.

Disbursements Were Lower Than Anticipated in April Through June. There was concern that state disbursements, for example for health and human services programs like Medi-Cal, would increase substantially in April through June as a result of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) public health emergency and ensuing recession. While spending on Medi-Cal and social services programs was higher than expected in January, it was only higher by about $1.5 billion across those three months. This is a relatively small increase in cash terms (and relative to the costs of these programs). Meanwhile, the state’s 2020-21 budget package took steps to begin payment deferrals to schools at the end of 2019-20. As a result, payments to schools in June of 2020 were only $300 million, compared to $6 billion anticipated earlier this year. On net, this means disbursements were actually lower in April through June than expected at the Governor’s budget.

Revenues Receipts Exceeded Expectations Somewhat. In March the state delayed the deadlines for filing and payment of the priority General Fund tax revenue sources from April 15 to July 15. This meant the state’s key revenue month of April was essentially delayed until after the end of the fiscal year. This action, along with declines in economic activity, had significant negative consequences for the state’s General Fund cash position. For example, SCO’s April projection assumed the state would receive only $19.8 billion in revenue from April through June of 2020. (For comparison, in 2018-19, the state collected roughly $52 billion over these three months). However, revenue receipts did not fall as dramatically as expected—the state received $23.5 billion from these sources in April through June. (Note these figures are reported on Controller’s cash basis, rather than Agency cash, which is the preferred method for tracking revenue collections against budget estimates. The nearby box describes the differences between these two sources.)

Agency Cash Versus Controller’s Cash

The state’s main tax revenue agencies (namely, the Franchise Tax Board and the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration) collect tax payments and then transmit those payments to the State Controller’s Office. The transmission of those receipts to the Controller can take a few days. Depending on whether the month ends with business days or not, there can be a one to four day delay between when payments are received by the tax agencies and when those payments are reported by the Controller. As a result, “agency cash” provides the best comparison point to track actual monthly revenue collections against budget act estimates. Controller’s cash, by contrast, is the best method for understanding the state’s monthly cash position. As a result, we rely on Controller’s cash data in this post, but our monthly revenue tracking posts use agency cash.

Key Special Funds in the Cash Cushion Were Not Substantially Affected. Finally, the state ended 2019-20 with $57 billion in available borrowable resources—about $6 billion more than was anticipated at the Governor’s budget. This is largely because the funds that make up largest components of the state’s cash cushion (as shown in Figure 3) are not immediately susceptible to changes in economic activity. A key example is the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA), which made up about 25 percent of the state’s internal borrowable resources on June 30, 2019.

Cash Management in 2020-21

When SCO prepared estimates for the cash situation in April, there was an unusually high amount of uncertainty about the state’s budgetary and cash situations, even for the following few months. By the time DOF and SCO prepared the cash management estimates for 2020-21 in July, a budget plan had been passed by the Legislature and the state had substantially more information about revenue collections for the 2019 tax year. While uncertainty about the state’s budget and cash situations is still high, the state’s cash management outlook for 2020-21 is positive.

Positive Cash Management Outlook

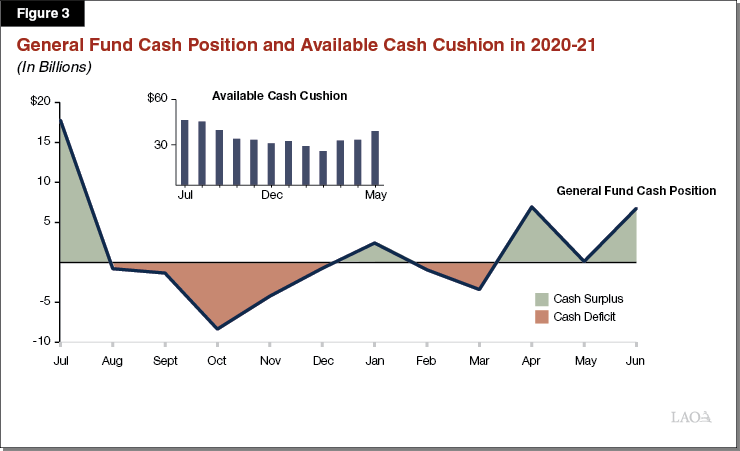

General Fund Cash Position. The blue line in Figure 3 shows the state’s General Fund cash position, as forecasted by DOF, through the fiscal year. As the figure shows, similar to a typical fiscal year, the state will experience cash deficits early in the fiscal year and cash surpluses later in the year. However, the state had a significant cash surplus in July as that was the major revenue collection month for the 2019 tax year.

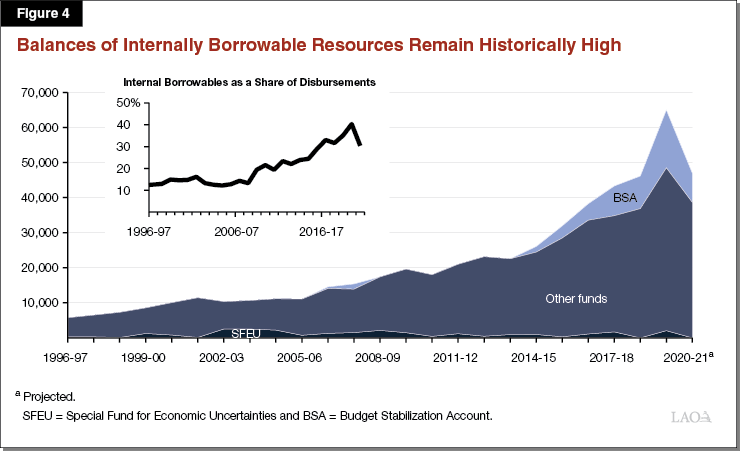

Available Cash Cushion. The inset of Figure 3 shows that the state’s available cash cushion is expected to stay around $30 billion to $40 billion for most of the year. At its lowest level, under these projections, the state’s available cash cushion would drop to about $24 billion in March of 2021. The key reason the state’s available cash cushion continues to remain sizeable is that, despite projected declines, the state’s balances of internal borrowables are expected to remain high in historical terms (see Figure 4). For example, while the state already withdrew nearly $8 billion from the BSA in July 2020, the balance of that account will remain above $8 billion for the rest of the fiscal year.

As a result of this strong available cash cushion, DOF does not expect the state to need to use external borrowing for cash management in 2020-21. This is very unusual for a recessionary year. In fact, while the state has not used external borrowing for cash management since 2014, in the 32 years between 1983 and 2014 the state issued at least one RAN in every single year except two (1995 and 2000). The fact that the state is unlikely to need a RAN in 2020-21 is a testament to the continued strength of the state’s cash position.

Important Factors When Tracking 2020-21 Cash Situation

Revenue Collections Pose a Major Source of Uncertainty. As is the case with the state’s budget condition, when it comes to cash management, the timing and amount of revenue collections is the major source of uncertainty in the projections. In general, if revenues are significantly higher (or lower) than the budget anticipated, it will change the state’s cash position for better (or worse). In fact, for July of 2020, revenue receipts were about $1.6 billion above expectations, which means the state’s cash position in that month is even better than anticipated at the time of budget act. (These figures come from the Controller cash reports. The preferred source for comparing budget projections to cash actuals are Agency cash reports, for example, as displayed on the LAO Economy and Taxes Blog.)

Significant Federal Reimbursements for COVID-19 Direct Expenditures Anticipated in 2020-21. Based on the latest information from the administration, the state currently is expected to spend $7.4 billion on direct COVID-19 expenditures this year. We expect the federal government—specifically the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)—to eventually reimburse the state for about 75 percent of these costs. In past disasters, however, the state has not received reimbursements until months (sometimes many years) after the disaster ended. In the case of COVID-19 expenditures, however, disaster response activities will take place over a shorter time period and FEMA has already provided the state advanced payments. As a result, the state is likely to receive reimbursements faster for COVID-19 than it has for other disasters. Nonetheless, the state’s direct expenditures on COVID-19 has significant cash flow implications because of the size of the expenditures and the delay when the reimbursement is received.

Deferred School Payments Have Implications for Late 2020-21, Early 2021-22. A final major factor in the state’s 2020-21cash situation in is payments to schools. The 2020-21 budget plans about $12.5 billion in school-related deferrals, which essentially means the state sends cash to schools for program operated in 2020-21 in 2021-22. (This deferral would be reduced to $5.9 billion if the state receives additional flexible funding from the federal government before October 15, 2020.) This means the state will have a higher than otherwise General Fund cash balance at the end of 2020-21, but then will need to make these payments in the first few months of 2021-22. (Conversely, school and community college districts will need to use internal sources or external borrowing to cover their short-term cash needs created by these payment deferrals.) While many developments between now and 2021-22 will affect the state’s cash position, the state’s cash plan for 2021-22 will need to accommodate unusually large cash payments to schools in these months.