March 12, 2021

The 2021-22 Budget

CalAIM: Equity Considerations

The California Advancing and Innovating Medi‑Cal (CalAIM) proposal is a far‑reaching set of reforms to expand, transform, and streamline Medi‑Cal service delivery and financing. This post—the third in a series assessing different aspects of the Governor’s proposal—analyzes equity considerations in the CalAIM proposal. The first post in this series provides an overview of CalAIM, including the key changes from last year’s withdrawn proposal, and analyzes overarching issues related to the proposal. The second post in this series analyzes CalAIM financing issues, including both the Governor’s funding plan for CalAIM as well as CalAIM’s policy changes related to Medi‑Cal financing. The fourth post in this series will assess how CalAIM could affect the care provided to seniors and persons with disabilities served by Medi‑Cal.

Background

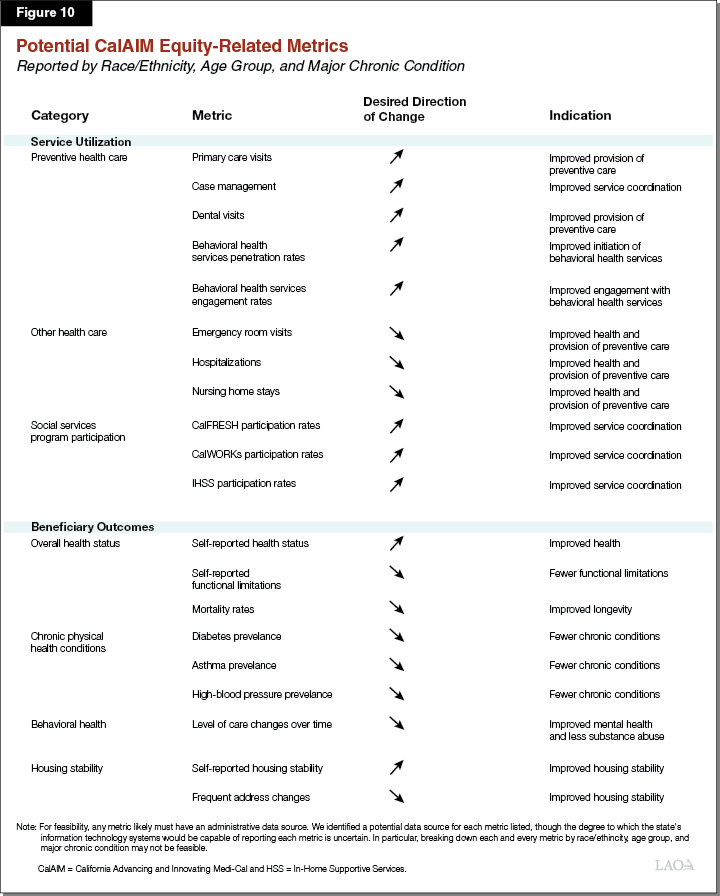

What Are Health Disparities and Health Equity? Health disparities and health equity are concepts that have no universally accepted definition. As such, this post uses a broad definition of the terms. Health disparities, under this broad definition, exist when a particular population group experiences systematically worse health or greater health risks than another population group. Population groups can be categorized in different ways, such as by demographic characteristics such as race and gender, geography, socioeconomic status, or other factors such as access to housing. Population groups that may experience worse health outcomes can include people of color, low‑income individuals, and homeless or housing‑insecure individuals. For instance, individuals experiencing homelessness are disproportionately likely to develop health conditions such as mental illness, which is associated with comorbidities and higher premature death rates. Most often, academic research measures health disparities in terms of differences in mortality, though other measures such self‑reported health status, diagnosed chronic conditions, and disability are sometimes used. The narrowing of health disparities corresponds to improvements in health equity, under this broad definition, while a widening of such disparities does the opposite. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) has accentuated health disparities in California as seen in Figure 1 which breaks down differences in life expectancy and COVID‑19 mortality by select racial or ethnic group.

Health Disparities Are Significantly Driven by a Variety of Medical and Nonmedical Determinants of Health. The determinants of health are the range of personal, social, environmental, and medical factors that influence health status. The following bullets distinguish and give a sense of the relative magnitude of the different medical and nonmedical determinants of health as drivers of health status. Figure 8, later in this post, breaks out many of the health determinants we identified in our review of the research and indicates which determinants different CalAIM components are intended to address.

- Medical Determinants. We find that differences in access to health care explain as much as 20 percent of health disparities. Notably, these medical determinants of health have been found to explain differences in health disparities even after accounting for other nonmedical determinants of health (which we discuss below). These differences include factors such as health insurance status and the quality of health care provided. Research indicates individuals from disadvantaged population groups often receive lower‑quality care than others from more advantaged population groups. For example, some studies suggest the existence of systemic disparities in the quality of preventive care different groups receive, leading to more preventable emergency department visits. Other research indicates that racial bias or deficiencies in cultural competency on the part of some clinicians can adversely affect the quality of care they provide.

- Nonmedical Determinants. Following our review of academic literature, we find that the nonmedical determinants of health likely are responsible for 80 percent or more of health disparities. Nonmedical determinants include social determinants (such as income, housing status, racism and discrimination, intentional and unintentional physical harm, and food security), health behaviors (such as diet and alcohol, tobacco, and drug use), and environmental factors (such as air or water quality). Nonmedical determinants of health are among the most systematic differences between certain population groups, such as racial and ethnic groups, and therefore explain much of the disparity in health outcomes between those groups. Accordingly, changes to such groups’ nonmedical circumstances could improve their health and, as a result, reduce health disparities.

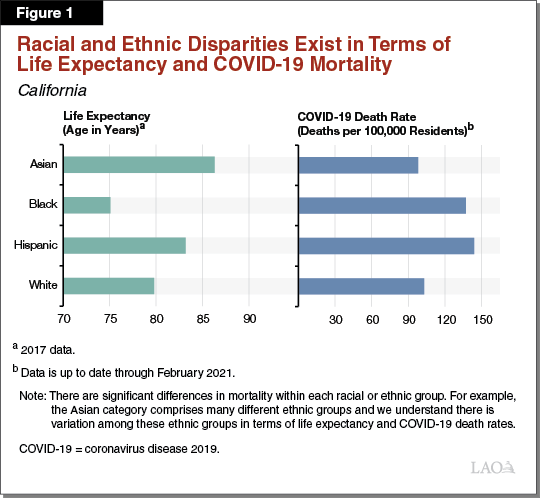

Medi‑Cal Provides Health Care Coverage to Populations Who Suffer Disparate Health Outcomes. Medi‑Cal provides health care coverage to more than one‑third of the state’s population. In part by covering low‑income individuals and families, Medi‑Cal disproportionately serves state residents whose socioeconomic and health characteristics are associated with poor health outcomes. For example, Medi‑Cal disproportionately covers state residents who are out of work, disabled, and/or do not have a college degree. Additionally, people of color are disproportionately represented in Medi‑Cal relative to the overall population. As Figure 2 shows, Medi‑Cal beneficiaries suffer worse health on a variety of dimensions compared to other state residents (which largely includes those with other forms of coverage but also the uninsured).

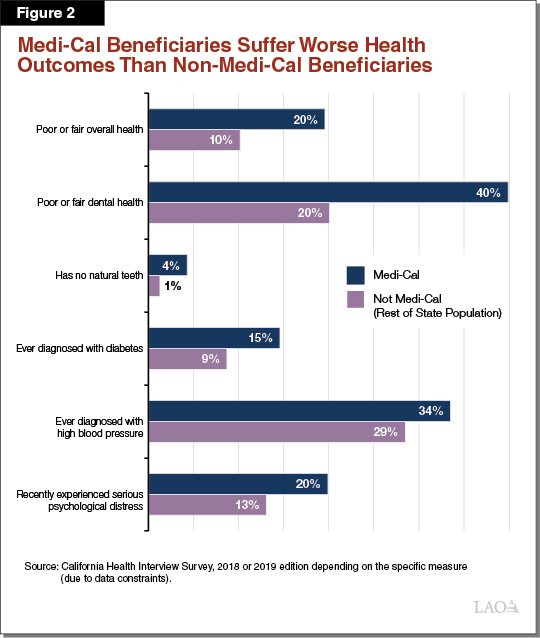

Health Disparities Exist Within the Population Served by Medi‑Cal. Health disparities are present among Medi‑Cal beneficiaries of different races or ethnicities. For example, as shown in Figure 3, compared to white Medi‑Cal recipients below age 65, non‑senior Black Medi‑Cal beneficiaries self‑report poor or fair health (the two worst ratings) at 30 percent higher rates. Hispanics below age 65 on Medi‑Cal, on the other hand, report poor or fair health at 24 percent lower rates than non‑senior white recipients.

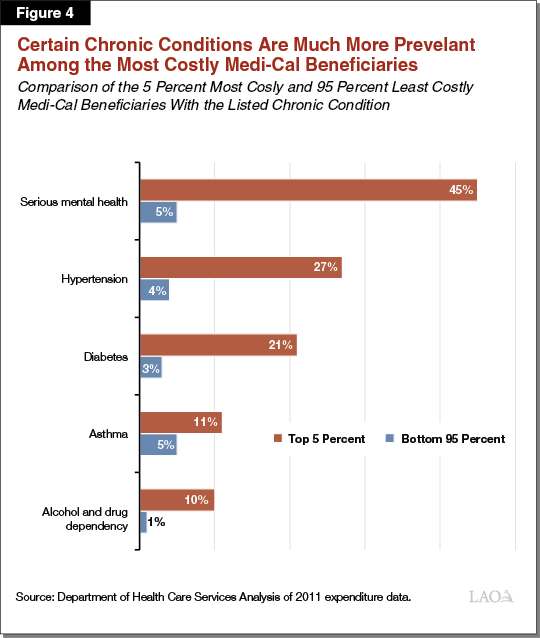

Health disparities also can be seen by looking at how service needs vary among Medi‑Cal beneficiaries. The top 5 percent most costly beneficiaries, on a per‑enrollee basis, utilize over 30 times as many resources, in dollar terms, as the least 50 percent costly. This illustrates that a relatively small number of Medi‑Cal beneficiaries have extremely disproportionate needs compared to more typical Medi‑Cal beneficiaries. Moreover, the top 5 percent most costly beneficiaries disproportionately suffer from certain chronic conditions—including mental illness, diabetes, hypertension, asthma, and alcohol and drug dependency—compared to Medi‑Cal enrollees overall. Such chronic conditions often are accompanied by comorbidities, which significantly impair the overall health of beneficiaries and can result in premature death. Figure 4 compares the prevalence of major chronic conditions among the top 5 percent most costly beneficiaries compared to Medi‑Cal enrollees overall. In addition to having low incomes, which is true for all Medi‑Cal enrollees, those who suffer from the listed chronic conditions may come disproportionately from particular population groups—such as individuals lacking stable housing or persons of color. For example, Black and Hispanic state residents have higher rates of diabetes and Black state residents experience homelessness at very disproportionate rates.

State Has Attempted to Reduce Health Disparities Through Various Medi‑Cal Initiatives. As previously discussed, the Medi‑Cal program serves individuals who disproportionately suffer from a myriad of health conditions and face other circumstances associated with poor health. Accordingly, changes to the Medi‑Cal program that result in improved access to care or quality of care have significant potential to reduce health disparities. In recent years, the state has implemented several reforms to the Medi‑Cal program, which, in concept, have potential to reduce health disparities across the state. These reforms included (1) expanding Medi‑Cal coverage to additional populations—such as to single adults under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) optional expansion and to undocumented immigrants under age 26—and (2) establishing programs that focus resources and attention on the highest‑risk, highest‑needs beneficiaries, often with the intent to prevent the worsening of severe health conditions. (The latter can serve to address disparities since certain population groups disproportionately may be high‑risk, high‑need.)

Three of these programs include:

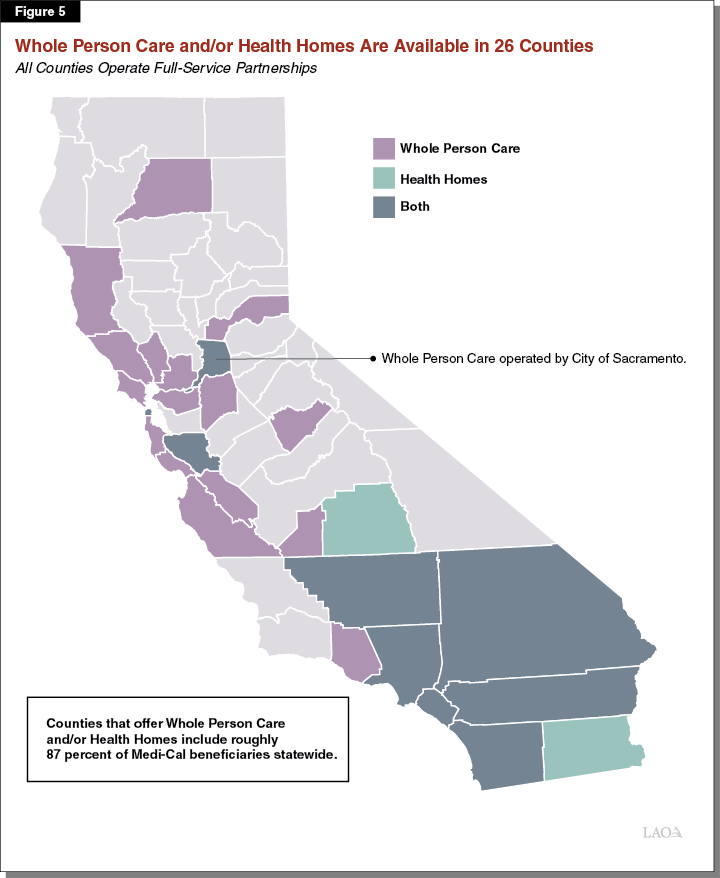

- Whole Person Care. The Whole Person Care program, which began in 2016, is a set of local pilot programs—typically run by county health agencies—to coordinate physical health, behavioral health, and social services for beneficiaries with the highest levels of need and/or risk. Each local Whole Person Care pilot determines target populations—among a predetermined set which includes, for example, high utilizers of services and homeless individuals—and develops strategies to tailor service delivery to those groups. The program is funded with a mix of federal and local funds and is set to expire at the end of 2021. Notably, additional state‑only funding also has been provided to Whole Person Care pilots to support housing services. Twenty‑four counties and one city have opted in to the Whole Person Care program. As of September 2020, about 86,000 people were participating in Whole Person Care.

- Health Homes. The Health Homes Program, which was implemented in 2018, has similar goals to the Whole Person Care program and provides extra services—including care management—to Medi‑Cal beneficiaries who suffer from chronic health and/or mental health conditions that result in high use of health care services. Twelve counties—with managed care plans arranging and paying for services within these counties—are participating in the Health Homes Program. As of March 2020, Health Homes served about 27,000 beneficiaries. This program also is set to expire at the end of 2021.

- Mental Health Services Act (MHSA) Full‑Service Partnerships. Approved by voters in 2004, MHSA places a 1 percent tax on incomes over $1 million and dedicates the vast majority of associated revenues to counties to provide mental health services. A substantial portion of the MHSA funding counties receive is required to be used on Full‑Service Partnerships, which provide intensive mental health and wraparound services—such as housing, employment support, and case management—to individuals with the greatest mental health needs. Full‑Service Partnerships are intended to provide services to populations—identified by counties—who disproportionately do not access mental health care. Counties use a variety of dimensions to identify these populations, which include (1) racial or ethnic characteristics, (2) housing status, or (3) criminal justice involvement. While not an explicit Medi‑Cal program, Full‑Service Partnerships provide services to many individuals eligible for Medi‑Cal and, accordingly, are often partially Medi‑Cal‑funded.

Figure 5 shows the counties that currently are participating in the Whole Person Care and/or Health Home programs.

Governor Proposed CalAIM as Part of the January 2020‑21 Budget Before Withdrawing the Proposal in May. CalAIM is a large package of reforms aimed at (1) reducing health disparities by focusing attention and resources on Medi‑Cal’s high‑risk, high‑need populations; (2) rethinking behavioral health service delivery and financing, (3) transforming and streamlining managed care, and (4) extending federal funding opportunities currently available under the state’s soon‑to‑expire 1115 waiver. Originally proposed in January 2020 as part of the 2020‑21 budget, CalAIM was withdrawn at the May Revision due to the COVID‑19 pandemic and its estimated effects on the state’s fiscal situation. To maintain continuity of certain Medi‑Cal programs such as Whole Person Care and the Dental Transformation Initiative—whose federal authorization under the state’s 1115 waiver would have expired at the end of 2020—the state secured a one‑year extension of the 1115 waiver. With this extension, the state’s 1115 waiver is set to expire on December 31, 2021.

Governor’s Proposal

Overall Proposal

Reintroduces CalAIM in Largely Similar Form to Last Year’s Proposal. The Governor’s 2021‑22 budget reintroduces CalAIM. The vast majority of proposed CalAIM reforms are essentially unchanged from last year’s proposal except as relates to their proposed implementation time line. The Governor’s reintroduced proposal emphasizes health equity as an important rationale for pursuing CalAIM. For a general overview of CalAIM, see our budget post, The 2021‑22 Budget: CalAIM: The Overarching Issues.

CalAIM Reflects One of the Governor’s Proposals Aimed at Health Equity. The Governor’s 2021‑22 budget includes a number of proposals that the Governor intends to improve health equity. While many of the new proposals aim to improve reporting on health equity metrics, others would expand benefits with the goal of more directly improving health equity. The major health and human services proposals either wholly or partially intended by the administration to address health equity include:

- Development of a Health and Human Services Agency‑wide health equity dashboard.

- An analysis of COVID‑19’s health equity implications.

- Health system‑wide equity reporting by the proposed Office of Health Care Affordability.

- Inclusion of health equity benchmarks among new standards and requirements that would be set on all managed care plans operating in the state, including those that provide coverage through Medi‑Cal and the state’s Health Benefit Exchange (Covered California).

- Expanded Medi‑Cal coverage of continuous glucose monitoring for beneficiaries with Type I diabetes.

- Permanent expansion of certain telehealth services under Medi‑Cal (which is intended to improve access to health care among Medi‑Cal beneficiaries).

Proposal Elements With Direct Health Equity Implications

CalAIM reflects a large suite of proposed reforms that touch nearly every aspect of Medi‑Cal. While essentially all of CalAIM has potential to improve health equity, certain CalAIM components are more directly intended to do so. This section describes the major components of CalAIM that are intended to directly have such impacts.

Better Identification of High‑Risk, High‑Need Beneficiaries Through Population Health Management Programs. Population health management programs represent a bundle of administrative activities—typically performed by managed care plans—that aim to (1) identify beneficiaries’ medical and nonmedical risks and needs and (2) facilitate care coordination and referrals. CalAIM would require all Medi‑Cal managed care plans to operate population health management programs. Managed care plans would be required to collect and analyze information on their members’ health status, service utilization history, and social needs. While existing data sources would form the basis of some of this information, a new standardized, statewide Individual Risk Assessment tool would be developed by the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) to ensure consistent information collection across managed care plans. With this information, managed care plans would assign their members into one of four risk categories: “low risk,” “medium and rising risk,” “high risk,” or “unknown risk.” While plans would remain responsible for connecting low‑risk members to preventive and wellness services, they would be responsible for providing increasing levels of care coordination and service linkages to their higher‑risk members. As discussed below, for many of their highest‑risk members, plans would be required to provide a higher level of case management services than they currently provide. Currently, at least 17 of the state’s 24 Medi‑Cal managed care plans operate public health management programs generally consistent with the population health management requirements of CalAIM.

Better Coordination of Services Through Enhanced Care Management (ECM). CalAIM proposes to create a new statewide managed care benefit, ECM, to provide intensive case management and care coordination for Medi‑Cal’s most high‑risk and high‑need beneficiaries (provided they are enrolled in managed care). The intent is for ECM to provide much more high‑touch, community‑centered care coordination services than generally are available to the targeted populations, which include, for example, high utilizers of emergency departments and members with unstable housing. The intent is for ECM to connect high‑risk, high‑need members to the appropriate services necessary for the improvement of health outcomes. Figure 6 shows how the target population of ECM compares to the target populations of the Health Homes Program and Whole Person Care. ECM would build upon case management strategies developed in these other programs that also were designed to focus resources and attention on the highest‑risk and highest‑need beneficiaries.

Figure 6

Comparing Target Populations: CalAIM (Enhanced Care Management) Versus Health Homes and Whole Person Care

|

CalAIM (Enhanced Care Management) |

Health Homes Program |

Whole Person Care |

|

Beneficiaries must be from one of the following categories: |

Beneficiaries must have a chronic condition in at least one of the following categories: |

Pilots were allowed to choose one or more of the following populations: |

|

|

|

|

Beneficiaries must also meet at least one of the following acuity/complexity criteria: |

||

|

||

|

CalAIM = California Advancing and Innovating Medi‑Cal and HHP = Health Homes Program. |

||

Provision of Broader Array of Nonmedical Supportive Services Through “in Lieu of Services” (ILOS). CalAIM would authorize managed care plans to provide an array of nonmedical services to their members. Under federal rules, these ILOS generally are nonmedical services that can be provided as alternatives to standard Medicaid benefits in the managed care delivery system. ILOS are intended to be provided in place of a more expensive standard Medicaid benefit. If states opt in to provide ILOS (and receive federal funds in respect of them), federal law requires that ILOS be optional for managed care plans to provide and beneficiaries to accept. Under CalAIM, DHCS has proposed a menu of 14 ILOS benefits that managed care plans could choose to provide beginning in January 2022. (Managed care plans that elect to offer ILOS benefits could select which specific benefits to provide.) Some of the proposed ILOS benefits have restrictions on how much they can be used or who is eligible for them, including benefits that are only available for use once in a beneficiary’s lifetime unless the managed care plan demonstrates why provision of the benefit for an additional time would be cost‑effective Figure 7 summarizes the proposed list of ILOS benefits in the Governor’s CalAIM proposal.

Figure 7

Proposed “In Lieu of Services” Benefits

|

Benefit |

Description |

|

Services to Address Homelessness and Housing |

|

|

Housing depositsa |

Funding for one‑time services necessary to establish a household, including security deposits to obtain a lease, first month’s coverage of utilities, or first and last month’s rent required prior to occupancy. |

|

Housing transition navigation servicesa |

Assistance with obtaining housing. This may include assistance with searching for housing or completing housing applications, as well as developing an individual housing support plan. |

|

Housing tenancy and sustaining servicesa |

Assistance with maintaining stable tenancy once housing is secured. This may include interventions for behaviors that may jeopardize housing, such as late rental payment and services, to develop financial literacy. |

|

Services for Long‑Term Well‑Being in Home‑Like Settings |

|

|

Asthma remediationb |

Physical modifications to a beneficiary’s home to mitigate environmental asthma triggers. |

|

Day habilitation programs |

Programs provided to assist beneficiaries with developing skills necessary to reside in home‑like settings, often provided by peer mentor‑type caregivers. These programs can include training on use of public transportation or preparing meals. |

|

Environmental accessibility adaptations |

Physical adaptations to a home to ensure the health and safety of the beneficiary. These may include ramps and grab bars. |

|

Meals/medically tailored meals |

Meals delivered to the home that are tailored to meet beneficiaries’ unique dietary needs, including following discharge from a hospital. |

|

Nursing facility transition/diversion to assisted living facilitiesc |

Services provided to assist beneficiaries transitioning from nursing facility care to community settings, or prevent beneficiaries from being admitted to nursing facilities. |

|

Nursing facility transition to a home |

Services provided to assist beneficiaries transitioning from nursing facility care to home settings in which they are responsible for living expenses. |

|

Personal care and homemaker servicesd |

Services provided to assist beneficiaries with daily living activities, such as bathing, dressing, housecleaning, and grocery shopping. |

|

Recuperative Services |

|

|

Recuperative care (medical respite) |

Short‑term residential care for beneficiaries who no longer require hospitalization, but still need to recover from injury or illness. |

|

Respite |

Short‑term relief provided to caregivers of beneficiaries who require intermittent temporary supervision. |

|

Short‑term post‑hospitalization housinga |

Setting in which beneficiaries can continue receiving care for medical, psychiatric, or substance use disorder needs immediately after exiting a hospital. |

|

Sobering centers |

Alternative destinations for beneficiaries who are found to be intoxicated and would otherwise be transported to an emergency department or jail. |

|

aRestricted to use once in a lifetime, unless managed care plan can demonstrate cost‑effectiveness of providing a second time. bNew benefit introduced this year. Restricted to lifetime maximum amount of $5000, unless beneficiary’s condition changes dramatically. cIncludes residential facilities for the elderly and adult residential facilities. dDoes not include services already provided in the In‑Home Supportive Services program. |

|

Improved Access to Behavioral Health Services. As was shown earlier in Figure 4, a higher proportion of Medi‑Cal’s highest‑need beneficiaries suffer from severe behavioral health conditions. Severe behavioral health conditions also are associated with worse physical health outcomes, as individuals with severe behavioral health needs often have difficulty navigating their physical health needs. In addition, data indicate that there are differences among Medi‑Cal populations in utilizing behavioral health services, which may reflect disparities in access to care. For example, Hispanic and Asian and Pacific Islander beneficiaries utilize Medi‑Cal mental health services at lower rates than other beneficiary groups. CalAIM includes a package of reforms to Medi‑Cal behavioral health service delivery, which generally are intended to (1) increase capacity to provide Medi‑Cal behavioral health services—for example, by leveraging additional federal funding for behavioral health services (including residential mental health services)—and (2) increase access to Medi‑Cal behavioral health care—for example, by revising medical necessity criteria to make it easier for beneficiaries to receive behavioral health services.

Assessment

This section provides our assessment of the potential of CalAIM to reduce health disparities and thereby improve health equity. Overall, we find that CalAIM has significant potential to improve health outcomes for the highest‑risk, highest‑need Medi‑Cal beneficiaries. Improved health outcomes could lead to improved health equity insofar as the improved outcomes are concentrated among certain groups who today disproportionately experience worse health outcomes. We find this likely would be the case under CalAIM, for reasons that we detail below.

While CalAIM has potential to improve health equity, we also find that it comes with significant risks, challenges, and limitations. These relate to implementation issues as well as oversight and evaluation.

While CalAIM Could Improve Health Equity…

CalAIM Would Increase Medi‑Cal’s Role in Addressing the Broader Determinants of Health

CalAIM Includes Initiatives Aimed at Addressing an Array of Medical and Nonmedical Determinants of Health. CalAIM would significantly expand Medi‑Cal’s role in addressing nonmedical determinants of health outcomes, primarily by encouraging managed care plans to offer beneficiaries a range of nonmedical ILOS benefits. For example, (1) housing navigation services and payments for housing deposits could help address housing insecurity, (2) home modifications for beneficiaries with asthma could help address harmful environmental exposure, and (3) medically tailored meals could help address unmet diet and nutrition requirements. Managed care plans also would take on a greater role in addressing nonmedical needs through the new ECM benefit, by coordinating some nonmedical community care and human services for high utilizers. Figure 8 provides examples of how various CalAIM proposals address particular determinants of health, including both medical and nonmedical ones.

Figure 8

CalAIM Proposals and Determinants of Health They Would Address

|

Health Determinanta |

Health Determinant Components |

Related CalAIM Proposal (Beyond ECM)b |

|

Medical (10% to 20%) |

Health insurance coverage |

Enrollment assistance for individuals transitioning from incarceration. |

|

Physical health care |

Extension of public hospital financing programs. |

|

|

Behavioral health care |

Behavioral health reforms. |

|

|

Dental health care |

Dental benefit expansion and incentive payments. |

|

|

Social circumstances (15% to 40%) |

Education |

None. |

|

Income |

None. |

|

|

Housing stability |

Housing and long‑term services and supports ILOS. |

|

|

Race |

State oversight of population health management. |

|

|

Neighborhood safety |

None. |

|

|

Behavior (30% to 50%)

|

Diet and nutrition |

Medically tailored meals for beneficiaries with unique dietary needs. |

|

Smoking |

None. |

|

|

Substance use |

Sobering centers ILOS. Extension of Drug‑Medi‑Cal Organized Delivery System. |

|

|

Level of physical activity |

None. |

|

|

Environment (5% to 20%) |

Exposure to pollution and contaminants |

Asthma remediation to mitigate environmental asthma triggers. |

|

aPercents in parentheses reflect the portion of health disparities explained by the listed determinant. They are listed as ranges due to the differences in academic research findings on the impacts of each determinant. bECM has potential to address most determinants and their components through the coordination of Medi‑Cal and non‑Medi‑Cal benefits. |

||

|

CalAIM = California Advancing and Innovating Medi‑Cal; ECM = enhanced care management; and ILOS = in lieu of services. |

||

By Better Connecting Individuals With a Larger Set of Medical and Nonmedical Services, Health Outcomes Could Improve. By providing a wider array of services and better connecting individuals with those services, CalAIM could improve health outcomes. Specifically, the new statewide ECM benefit would require plans to connect those individuals with higher needs to a more comprehensive set of health care and social support services. Improving access to services affecting determinants of health could improve individuals’ outcomes. In addition, the package of the behavioral health reforms—generally intended to increase capacity for services provided and access to care—could improve overall health outcomes given that severe behavioral health conditions are associated with a variety of physical health comorbidities. Additionally, ILOS benefits have the potential to improve health outcomes for Medi‑Cal beneficiaries by providing them access to services that address some of the underlying nonmedical determinants of their health, like housing. The addition of asthma remediation to the list of ILOS benefits is particularly promising, as it would remove triggers from the home environment that lead to worse health outcomes for Medi‑Cal beneficiaries with asthma.

Possible Improvements in Health Outcomes Likely Would Be Concentrated Among Individuals Who Currently Suffer the Worst Health Outcomes. Many major CalAIM initiatives—including those targeting the nonmedical determinants of health—are aimed at improving health outcomes for Medi‑Cal’s highest‑risk, highest‑need beneficiaries. Many of the intended beneficiaries are homeless, have mental illness, are at risk of institutionalization in nursing homes, and/or have one or more serious chronic physical health conditions.

CalAIM’s Targeting of Medi‑Cal’s Highest‑Risk, Highest‑Need Beneficiaries Could Serve to Reduce Disparities and Improve Health Equity. Any improved health outcomes that result from CalAIM could improve health equity insofar as the improved outcomes are concentrated among groups that disproportionately suffer poor health outcomes today. The following bullets describe several of the ways CalAIM could improve health equity by narrowing disparities between different groups.

- Narrowing Disparities Between Low‑ and High‑Income Californians. Medi‑Cal exclusively serves low‑income individuals. As Figure 2, shows, Medi‑Cal beneficiaries generally suffer worse health outcomes than non‑Medi‑Cal beneficiaries. Therefore, if CalAIM is successful in improving the health of even a subset of Medi‑Cal beneficiaries, the health disparities between low‑ and high‑income state residents could narrow.

- Narrowing Disparities Between Those With and Without Stable Housing. Key components of CalAIM aim to improve the health and other outcomes for individuals experiencing or at risk of homelessness. (Medi‑Cal likely is the main source of health care coverage for state residents who are homeless.) These include, but are not limited to, targeted enrollment of homeless individuals into ECM, the addition of new housing services through ILOS (including paying housing deposits and utilities), and medical respite for individuals who no longer need hospital‑level care but do not have a safe place to convalesce. Accordingly, if successful, CalAIM could improve health outcomes for those without stable housing and thereby narrow the disparities between those without stable housing and those who are stably housed.

- Narrowing Disparities Between Certain Racial or Ethnic Groups. Certain population groups within Medi‑Cal generally have higher risks and/or needs. For example, Black Medi‑Cal beneficiaries report worse overall health and suffer from chronic conditions such as diabetes at higher rates than other racial or ethnic groups. Moreover, Black state residents as a whole experience homelessness at highly elevated rates. Accordingly, if CalAIM is successful in improving health outcomes among Medi‑Cal’s highest‑risk, highest‑need beneficiaries, these improvements likely would be concentrated among individuals from certain racial or ethnic groups, which could reduce disparities between such groups. In addition, persons of color are disproportionately represented among seniors in the Medi‑Cal program compared to seniors living in the state as a whole. Many CalAIM reforms could improve care for Medi‑Cal’s senior population, which, in turn, could disproportionately benefit the state’s seniors of color.

CalAIM Builds on the Potential Promise of Existing Programs

CalAIM Consolidates and Scales up Health Homes and Whole Person Care. As previously discussed, CalAIM would build upon existing programs—Whole Person Care and Health Homes—that would end once CalAIM is launched. CalAIM does this in a number of ways. First, by requiring managed care plans to establish population health management programs and provide ECM on a statewide basis, CalAIM would expand certain service components of Whole Person Care and Health Homes to all 58 counties. Second, while ILOS offerings would vary regionally depending on which ILOS plans elect to provide, overall, such services offerings are likely to expand relative to today under existing programs. Third, CalAIM would consolidate Whole Person Care and Health Homes within a single suite of programs operated or arranged by managed care plans. Because Whole Person Care and Health Homes target overlapping, though not identical, populations, challenges have been reported by program administrators around determining which program should serve which populations. By consolidating the services offered by these programs under managed care, CalAIM eliminates this potential fragmentation challenge. The text box below briefly discusses how CalAIM relates to Full‑Service Partnerships.

Comparing CalAIM and Full‑Service Partnerships

The approach of California Advancing and Innovating Medi‑Cal (CalAIM) is similar to that of Full‑Service Partnerships in that both provide supportive services (including housing) and care coordination to individuals with severe mental illness. While Full‑Service Partnerships would continue in conjunction with CalAIM, the similarity between the approaches provides the Legislature an opportunity to (1) draw lessons from these longstanding Mental Health Services Act programs in its deliberations over CalAIM and (2) explore where coordination between CalAIM programs and Full‑Service Partnerships might improve service delivery and outcomes.

Evaluations of Existing Programs Reveal Some Promising Results. Evaluations have been carried out of Whole Person Care, Health Homes, and Full‑Service Partnerships. These evaluations show significant progress has been made under these programs in establishing the infrastructure needed to identify and serve high‑risk, high‑need beneficiaries. Infrastructure improvements include the formation of care coordination and outreach teams, the execution of multiagency data‑sharing agreements, and the establishment of incentive payments to improve local service delivery. In the case of Whole Person Care, these infrastructure improvements facilitated the enrollment of over 100,000 program beneficiaries by the third year of implementation (almost half of whom were experiencing homelessness, a population that can be hard to reach and engage in services).

Additionally, the evaluations of these existing programs provide some evidence of improvements in clinical care and health outcomes. For example, Whole Person Care enrollees reported improvements in their overall and mental health, Health Homes participants visited emergency departments at a significantly lower rate after one year of enrollment, and Full‑Service Partnership clients utilized primary health care at higher rates than before they joined the program. (Full‑Service Partnership clients also demonstrated lower rates of criminal justice involvement than prior to program participation.) However, as we discuss below, these evaluations fall short of conclusively demonstrating improved clinical care and health outcomes as a result of these programs. Final evaluations of Whole Person Care and Health Homes have yet to be completed, which we expect will shed additional light on the impacts of these programs.

…The Proposal Faces Several Risks, Challenges, and Limitations

Implementation Issues

CalAIM Builds on Programs Whose Impacts Are Not Fully Understood. As previously noted, evaluations of existing programs that major new CalAIM initiatives would build on or otherwise draw inspiration from do not conclusively demonstrate the effectiveness of these programs in improving care delivery and health outcomes. The following bullets highlight several of the challenges that existing programs have faced and why, in our assessment, the evaluations do not conclusively show improved outcomes.

- Challenges Developing Population Health and Service Delivery Infrastructure in Programs. While clear progress was made under Whole Person Care and Health Homes in establishing cross‑agency collaboration, data sharing, and program linkages, challenges also arose. For example, despite the execution of a new data sharing agreement under Whole Person Care, half of all pilots reported continued difficulties in obtaining necessary data for successful program implementation. Additionally, pilots commonly reported a lack of available housing and behavioral health services capacity constraints as impediments to improving enrollee outcomes.

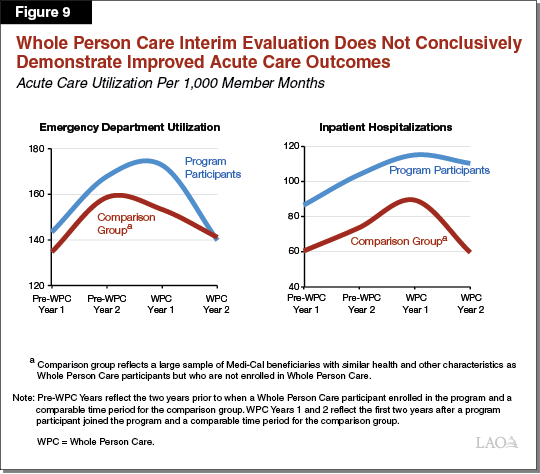

- Clinical Care and Health Outcome Improvements for Whole Person Care Participants Were Not Systematically Different Than Similarly Situated Non‑Participants. We previously highlighted several clinical care and health outcome improvements that were found in evaluations of existing pilot programs that CalAIM builds upon or draws inspiration from. In our assessment, however, these evaluations fall short of conclusively demonstrating improved outcomes as a direct result of the pilot programs. As shown in Figure 9, while the interim evaluation of Whole Person Care shows certain improvements in care delivery among program participants, these improvements do not appear to differ systematically from a comparison group of fairly similarly situated Medi‑Cal beneficiaries not participating in Whole Person Care. This similarity could indicate that the improved outcomes reported for program beneficiaries may not be due to the impacts of the programs but instead due to other factors, such as the tendency of individuals experiencing acute health crises to improve in health following acute episodes (provided adequate medical care is delivered). Moreover, differences in acute care utilization between Whole Person Care participants prior to their enrollment in Whole Person Care and the comparison group raise questions about whether the two groups are similar enough to compare for the purpose of judging the impacts of Whole Person Care. All that said, the evaluations only cover the expiring pilot program’s earliest years of implementation. Positive impacts directly related to program implementation could take longer to arise. The forthcoming evaluations should cover the impacts of the latter years of implementation and, therefore, fundamentally could change our understanding of the impacts of these programs.

- Comparative Effectiveness of Different Approaches Among Program Administrators Not Evaluated. The Whole Person Care and Health Homes interim evaluations primarily analyze the impacts of the pilot programs from a total statewide perspective, while also highlighting differences in approach among the different participating program administrators. Per the state’s evaluation instructions, however, the evaluations do not focus on the comparative effectiveness of different approaches in terms of program structure, care coordination, and population targeting and outreach across different participating program administrators. We understand that evaluations of Full‑Service Partnerships similarly have rarely focused on comparative effectiveness of different approaches across partnership participants. While we understand that different approaches across the state in implementing a program may be warranted given differences in local environments and needs, we believe different programmatic approaches may produce different results. Evaluation of how pilot results compare given differences in approach could help the Legislature better determine which models of care to expand to additional localities.

Based on the above findings related to the programs CalAIM would build upon, it is difficult to definitively expect CalAIM to achieve its intended outcomes related to improvements in health equity.

While ECM Target Populations Generally Are Reasonable, They May Be Overly Broad for Targeting Those With Greatest Needs. Although the administration says it intends for ECM to be targeted at the top 1 percent of Medi‑Cal utilizers, the proposed criteria for ECM eligibility may apply to a much larger share of the overall Medi‑Cal population. Some managed care plans have suggested that, as currently written, the proposed eligibility criteria could apply to a significant share of their enrollees. However, as the administration releases further information on CalAIM, it may continue to clarify the proposed ECM eligibility criteria such that it applies to a narrower group of current Medi‑Cal enrollees.

Medi‑Cal Beneficiaries Not Enrolled in Managed Care Would Not Be Able to Access Certain New CalAIM Benefits. CalAIM’s most significant benefit expansions—ECM and ILOS—are proposed to be available only through managed care, through which more than 11 million Medi‑Cal beneficiaries receive services. Medi‑Cal’s more than 1 million beneficiaries eligible for comprehensive coverage who receive care through Medi‑Cal’s fee‑for‑service delivery system would not be eligible for these services. Many of these beneficiaries are members of populations with high needs, such as elderly and disabled individuals and foster youth, who potentially could benefit from the expanded services and care coordination under CalAIM. As part of CalAIM, DHCS intends to develop a specialized model of care for current and former foster children. At this time, however, how this new specialized model of care would allow current and former foster children to avail themselves of CalAIM’s new managed care benefits is unclear.

CalAIM as a Package of Reforms Only Would Address Certain Drivers of Health Disparities. Although CalAIM would address a wide range of underlying determinants of health, there are some significant nonmedical drivers of health disparities that it does not directly address. For example, while some ILOS benefits would address particular nonmedical determinants of health—in particular, housing insecurity—they would not directly mitigate the negative consequences of other nonmedical determinants, such as unemployment or education level. Similarly, although a healthy diet and regular exercise are two health behaviors that have a significant impact on health outcomes, the ILOS medically tailored meals benefit is the only one with any direct relationship to these behaviors.

Constraints in Supply Could Limit Effectiveness of Reforms. Whether the CalAIM package would be able to effectively reduce health disparities within Medi‑Cal depends, in part, on the degree to which managed care plans would be able to take advantage of and expand community resources to serve the broader, nonmedical needs of their members. Accordingly, limits in the availability of community resources could limit the effectiveness of the CalAIM initiative, as well as the time frame for realizing potential health equity benefits. For example, constraints in the local housing supply in certain communities could make assisting members in obtaining appropriate housing a challenge for managed care plans. Notably, limited housing availability has been among the most common challenges cited by implementers of the Whole Person Care pilots in addressing the nonmedical determinants of health.

Plan Discretion Makes Access to ILOS Benefits Uncertain. Federal law requires the state to allow Medi‑Cal managed care plans to choose whether—and which—ILOS benefits to offer. If managed care plans do not widely opt to provide ILOS benefits, the availability of these new services could be more limited in scope than the state ultimately desires. Furthermore, the degree to which managed care plans would elect to offer ILOS benefits would vary from county to county. As a result, which specific ILOS benefits would be available to a Medi‑Cal beneficiary would vary based on where they live in the state and what managed care plan they are enrolled in. In addition, plans may vary in determining which beneficiaries receive ILOS benefits. These potential inconsistencies in access to ILOS benefits could reduce CalAIM’s effectiveness in promoting health equity statewide. Therefore, while the proposed ILOS benefits under CalAIM have significant potential to reduce health disparities in the Medi‑Cal program, these uncertainties in access to ILOS benefits makes the degree to which this would occur unclear. However, although ILOS benefits are proposed to be optional for managed care plans to provide at this time, the administration has indicated that including these new benefits in CalAIM reflects an opportunity to assess the feasibility of converting some services proposed under ILOS into statewide mandatory benefits in the future. To the extent that more plans provide these services in the future—either voluntarily or as a result of a statewide mandate—disparities in access to these services, and thus health disparities in the Medi‑Cal program, could be further reduced.

Strategy for Ensuring Lack of Bias in Population Health Management Program Implementation Deserves Scrutiny. Under the CalAIM’s population health management proposal, managed care plans would use algorithms to assist in identifying their highest‑need, highest‑risk enrollees (in addition to using traditional identification means such as referrals and self‑assessments). Research has shown such algorithms sometimes are biased, such that they systematically refer fewer members of certain racial groups for additional medical care. These biases could inadvertently contribute to existing health disparities. As a result, the administration has proposed that managed care plans be required to identify any potential biases in their algorithms and correct for them. However, the administration has not yet provided guidance on how managed care plans should identify and correct for bias in their algorithms.

Evaluation and Oversight Issues

Unclear How Progress in Improving Equity Would Be Measured and Evaluated. By improving health outcomes for many of the state’s highest‑risk, highest‑need residents, CalAIM is intended to promote health equity. However, to date, the administration has not released a detailed plan for how CalAIM would be evaluated. Without careful and robust monitoring and evaluation, determining whether CalAIM is proving successful in promoting health equity would be difficult. Moreover, CalAIM may provide the state with new opportunities to track Medi‑Cal beneficiary outcomes, the improvement of which could help set the foundation for future progress on health equity. As previously discussed, under CalAIM, managed care plans would be required to build, improve, and maintain significant infrastructure for the purpose of identifying high‑risk, high‑need beneficiaries and tracking their connection to services. This, in turn, presents the state with an opportunity to draw on this data to better track Medi‑Cal beneficiary outcomes and needs, as well as CalAIM’s overall performance in improving health outcomes and equity. For example, the state potentially could track (1) rates of housing instability among Medi‑Cal beneficiaries; (2) changes in Medi‑Cal beneficiaries’ risk scores; (3) progress in linking high‑risk, high‑need beneficiaries to services; and (4) various other beneficiary outcomes and CalAIM impacts. As yet, however, the administration has not clearly articulated how improved managed care plan infrastructure related to population health management would translate into improved statewide performance monitoring through public reports and dashboards.

Key Takeaways and Issues For Legislative Consideration

CalAIM Has Potential to Improve Health Equity... As mentioned above, health disparities are driven in large part by nonmedical determinants of health. By encouraging managed care plans to provide nonmedical services, CalAIM has potential to address some of the underlying causes of health disparities, and thereby promote health equity. Additionally, CalAIM would direct more health care resources toward the highest‑need, highest‑risk beneficiaries. Targeting enrollees who systematically face the worst health outcomes also has the potential to improve health equity in Medi‑Cal.

…But Success Is Far From Certain. In addressing the nonmedical determinants of health, CalAIM is intended to mitigate some of the most significant social and policy challenges the state faces—including many challenges that have traditionally been considered beyond the scope of health care policy. Due to the scale of these challenges, whether CalAIM can make a meaningful impact on them is unclear. Evaluations of similar programs, such as the Health Homes Program and Whole Person Care, have yet to find any conclusive evidence that the major interventions included in CalAIM—such as ECM and ILOS—lead to significant reductions in health disparities.

Legislature Could Consider Which Nonmedical Determinants Medi‑Cal Is Most Suited to Address. While CalAIM is intended to address several nonmedical determinants of health, there are other nonmedical determinants of health that it is not positioned to address. For example, as discussed earlier, overall economic well‑being and educational status also are key nonmedical determinants of health that drive disparities in health outcomes among population groups. To address these other sources of health disparities, the Legislature might need to pursue distinct policy changes that are better equipped to improve outcomes in these areas. In addition, for the nonmedical determinants of health that CalAIM is intended to address, whether Medi‑Cal is the program best equipped to improve outcomes is unclear. For example, there are other state departments that aim to address housing issues (a key nonmedical determinant of health that CalAIM intends to address). Given these considerations, the Legislature may wish to consider which nonmedical determinants of health Medi‑Cal is most primed to address, and consider whether additional resources should be provided to other state programs to address nonmedical determinants of health statewide. Importantly, without Medi‑Cal playing a role, the state would sacrifice the opportunity to draw down additional federal funding for these services.

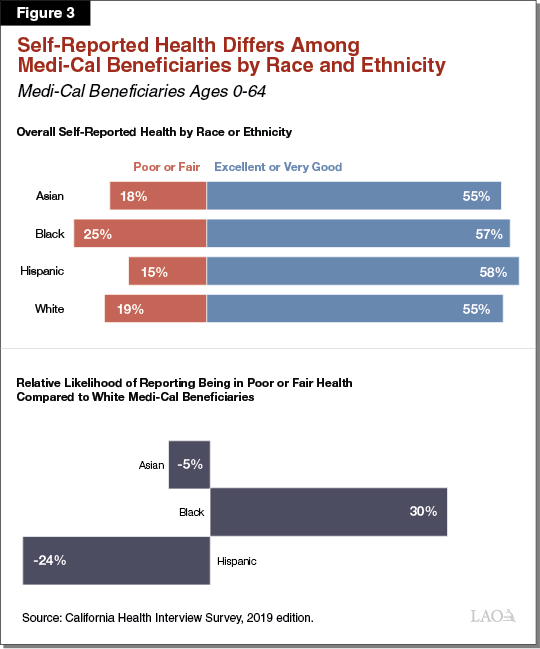

Recommend Formulating Specific Equity Metrics to Ensure CalAIM Is Meeting Equity Goals. While CalAIM holds promise in improving health equity, its success is not certain. This makes monitoring the performance of CalAIM critical. To do so, we recommend that the Legislature formulate a set of metrics related to the health equity goals of CalAIM and require the administration to report on these metrics periodically. In addition to including metrics related to care delivery and utilization, we also would encourage inclusion of metrics that more directly indicate beneficiary health outcomes to the fullest extent possible. Figure 10 lists examples of health equity metrics that, should systems allow, we would recommend be included in periodic public reports or a dashboard related to CalAIM. (This list is not meant to be exhaustive.) Creation of a CalAIM equity reporting mechanism or dashboard could be considered in concert with the Health and Human Services Agency’s effort to create a dashboard tracking health disparities beyond Medi‑Cal.