LAO Contact

April 21, 2021

The State Appropriations Limit

- Introduction

- How the Limit Works for the State

- How the Limits Work for Other Entities

- Why Is the SAL a Constraint for the State Now?

- How Might the SAL Limit State Spending Growth?

- Administrative Issues in the SAL

- How Can the Legislature Respond?

- Constructing a Plan

Executive Summary

The State Appropriations Limit (SAL) Likely to Limit Spending Growth in the Budget Year and Future Years

SAL Will Be an Important Issue at May Revision. Proposition 4 (1979) established an appropriations limit on the state and most types of local governments. The appropriations limit is based on appropriations from tax revenue. If the state has revenues above the limit over two consecutive years, the State Constitution requires the state to split the excess between taxpayer rebates and additional spending on schools. In the Governor’s budget, the administration estimated the state would have revenues in excess of the limit in some years between 2018‑19 and 2021‑22. Specifically, according to initial estimates, the state has excess revenues of about $100 million between 2018‑19 and 2019‑20 and about $500 million between 2019‑20 and 2020‑21. These amounts represent less than 1 percent of the limit in these years. The administration will update its estimates at the May Revision. In light of strong revenue collections that have occurred since January, we anticipate responding to the requirements of the SAL will be an important issue for the state budget this year.

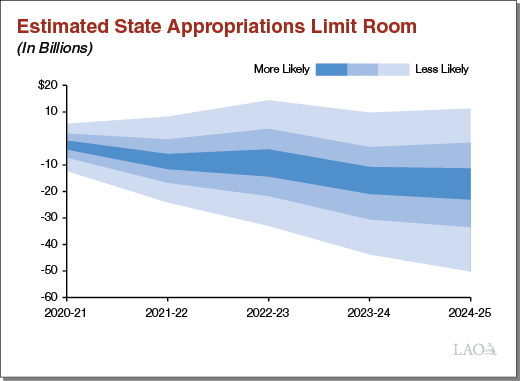

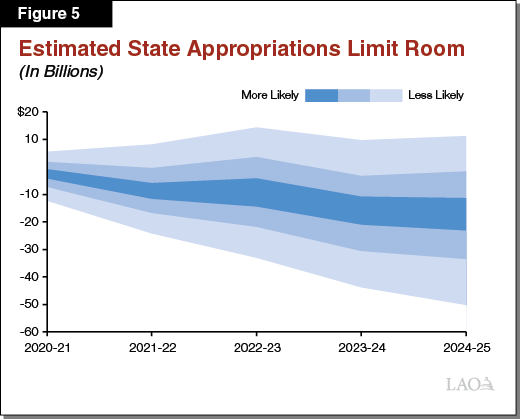

SAL Likely to Be a Major Issue Over the Next Few Years. Our analysis suggests the SAL will be an even more important factor in the state budget in the coming years. The figure below shows our projections of the likely “room” under the limit over the next few years. Projections of the amount of room under the limit are highly uncertain, as shown by the wide range of possible outcomes in the figure. That said, under the vast majority of likely outcomes, we anticipate the state will have “negative room.” That is, the state either would need to reduce taxes or issue refunds to taxpayers and make additional payments to schools in these amounts. Further, without significant budget changes, the state likely does not have the capacity for new services or program expansions.

Why Is the Limit an Issue Now?

There are two primary reasons that room under the limit has diminished. First, growth in personal income tax revenue—the state’s largest revenue source—has exceeded the SAL’s growth rate. There are a few reasons for this, but two important factors are: (1) the state’s tax rate structure combined with (2) faster income growth among high‑income earners. As a result, year‑to‑year growth in appropriations has been higher than increases in the SAL. Second, constitutionally required school spending—driven by faster state revenue growth—has increased faster than school limits. Because the state absorbs appropriations above school limits, this trend has resulted in diminished room for the state.

How Can the Legislature Respond?

Options for Legislative Consideration. In the coming months and years, the Legislature will face decisions about how to respond to state tax revenues nearing the limit. This report describes various options that the Legislature could consider in response. They fall into five categories: (1) issue tax refunds and allocate excess revenues to schools, (2) increase spending on excluded purposes, (3) reduce proceeds of taxes and spending, (4) make statutory changes to the SAL, and (5) go to the voters.

Short‑ and Long‑Term Options Needed. Few of these options, in isolation, are likely to be sufficient to keep the state from exceeding the limit over the next few years. For example, this year, the Legislature could decide to issue refunds and provide additional funding to schools. This response might not be sustainable over the long term, however. As existing program costs increase, revenues available for appropriation could be insufficient to meet current service levels. Consequently, changes to the state’s revenues and expenditures would be required. Alternatively, should the Legislature pursue statutory changes to the SAL, those changes would be unlikely to be sufficient to avoid reaching the limit in the next few years. In that case, considering placing a measure before the voters could be needed.

Constructing a Plan. We recommend the Legislature construct a short‑ and long‑term plan for how it wishes to respond. To aid the Legislature in constructing this plan, the figure below summarizes the options presented in this report, when each option could take effect, and our estimate of the potential magnitude of each potential change.

Consider Timing and Amounts of Various Policy Options

|

Policy Option |

Timing |

Amount |

|

Issue tax refunds and allocate excess revenues to schools |

Immediate. Legislature can pursue immediately. However, significant, ongoing refunds and school allocations could require more structural changes to the state budget. |

Tens of billions |

|

Increase spending on excluded purposes |

Immediate. The Legislature can increase spending on excluded purposes in the 2021‑22 budget. |

Billions |

|

Reduce proceeds of taxes and spending |

Depends. The Legislature can pursue these reductions immediately, but major reductions to state services would take time to implement. |

Tens of billions |

|

Make statutory changes to the SAL |

||

|

Immediate. Legislature could implement in budget trailer bill legislation in 2021‑22. |

Five billion |

|

A Year or So. The Legislature could enact the statute in budget trailer bill legislation, but the policy change would take the administration time to implement. |

Up to ten billion |

|

Go to the voters |

||

|

A Year or More. The Legislature could place a measure on the ballot to request a change. |

Unlimited |

|

Tens of billions |

|

|

A couple billion |

|

|

Unlimited |

Introduction

In the late 1970s, voters passed Proposition 4 (1979), which added Article XIIIB to the State Constitution. Article XIIIB established an appropriations limit on the state and most types of local governments. (These limits also are referred to as “Gann limits” in reference to one of the measure’s coauthors, Paul Gann.) The appropriations limits later were amended by Proposition 111, which was passed by voters in 1990. The purpose of the appropriations limits is to keep real (inflation adjusted) per‑person government spending under 1978‑79 levels. For more information about the history of the appropriations limit, see our previous reports, including The 2017‑18 Budget: Governor’s Gann Limit Proposal, The State Appropriations Limit, and An Analysis of Proposition 4 the Gann “Spirit of 13” Initiative.

At the time of Governor’s budget this year, the Department of Finance (DOF) expects the state to collect revenues in excess of the limit in some years between 2018‑19 and 2021‑22. The administration will update this estimate at the May Revision. As such, the state appropriations limit (SAL) or “the limit” will be an important issue in state budgeting this spring. Perhaps more importantly, as discussed in this report, our estimates suggest the growth in state appropriations subject to the limit are likely to significantly outpace growth in the limit in the coming years. Absent a revenue downturn in the coming years, the Legislature most likely will have to make major changes to state budgeting.

This report begins with background information on how the limit works for the state, school districts, and local governments. Next, we explain why the limit is a constraint for state government. Importantly, our analysis suggests this constraint will be a major issue for California in the next few years. Then we discuss some administrative issues in the appropriations limits for both the state and school districts. We conclude with a variety of short‑ and long‑term policy options—both of which we think the Legislature will need to take—in response to the issue.

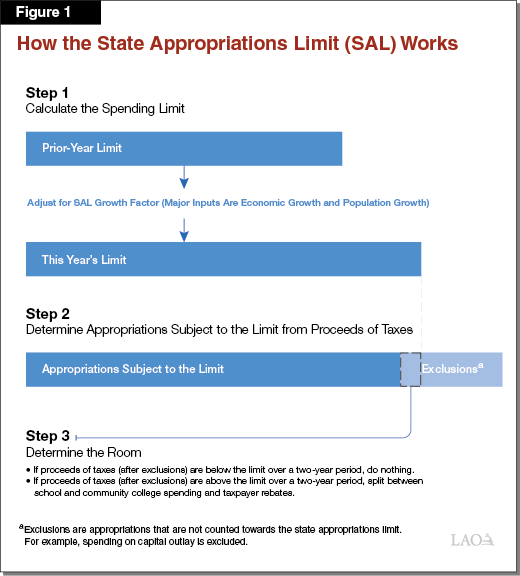

How the Limit Works for the State

The SAL calculation has three steps: (1) calculate the spending limit, (2) determine appropriations subject to the limit, and (3) determine the room (if any). These steps are described in this section and summarized in Figure 1. DOF has the responsibility for executing these calculations. While the Legislature determines annual appropriations and defines key parameters of the calculation in statute, it does not have a direct role in administering the limit.

Calculate the Spending Limit

First, the state calculates the limit. This limit, as shown in the top part of Figure 1, is the previous year’s limit grown for the SAL growth factor.

Build Off of 1978‑79 Base Year. The provisions of Proposition 4 keep real per capita government spending under the 1978‑79 level, adjusted for population. As such, today’s limit is based on the total level of state spending, adjusted for a variety of factors, in 1978‑79 (known as the base year). In determining the base year, the Legislature had to make a variety of choices about how to count various appropriations. For example, the Legislature had to determine which types of spending would count at the state level versus the local level.

Increase Limit by Growth Factor. Each year, the state grows the limit by multiplying the previous year’s limit by a growth factor. The two most important inputs to the growth factor are:

- Measure of Economic Growth. This growth factor is calculated by taking: (1) California fourth quarter personal income, as measured by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, divided by (2) the civilian population of the state, as measured by DOF. (The State Constitution refers to this measure as the “cost‑of‑living” adjustment.)

- Measure of Population Growth. The SAL growth factor’s second major input is change in population. To measure population, the formula uses a weighted average of the change in the school population and the change in the state’s civilian population.

Determine Appropriations Subject to the Limit

Second, the state determines appropriations subject to the limit. These are determined by first estimating proceeds of taxes from all state sources and then subtracting exclusions.

Determine Proceeds of Taxes. All state proceeds of taxes are included in the limit regardless of their fund source. This means the limit applies not only to the General Fund but also all special funds that receive revenues from taxes. Revenues from nontax sources—like user fees—are not included in the SAL. Some revenues, such as taxes on cigarettes from Proposition 56 (2016), were excluded from the SAL by the voters. Federal funding also is excluded from the SAL. So, the first step in calculating appropriations subject to the limit is to estimate the total proceeds of taxes subject to the limit.

Assume All Revenues Subject to the Limit Are Appropriated. Under the constitutional provisions of the SAL, all tax revenues are considered appropriated unless explicitly excluded. For example, reserve deposits are considered appropriations in the year the deposit is made. This means there is no such thing as “unappropriated” tax revenues.

Reduce Appropriations for Exclusions. The Constitution allows the state to reduce proceeds of taxes for certain exclusions. These exclusions are:

- Subventions to Local Governments. The Constitution allows subventions to local governments to be counted against that local government’s limit (instead of the state’s limit). The term “subvention” was not defined in Proposition 4. The implementing legislation passed in 1980 established the definition of subvention as: “only money received by a local agency from the state, the use of which is unrestricted by the statute providing the subvention.”

- Debt Service. The Constitution defines this exclusion as: “appropriations required to pay the cost of interest and redemption charges ... on indebtedness existing or legally authorized as of January 1, 1979, or on bonded indebtedness thereafter approved according to law by a vote of the electors...” In implementing legislation, the Legislature chose not to include some outstanding debt that existed in 1979—such as unfunded pension liabilities—as an exemption under this language.

- Federal and Court Mandates. The Constitution created an exclusion for appropriations that are required to comply with mandates imposed by the courts or the federal government. To qualify as a mandate for SAL purposes, the federal or court requirement must result in an expenditure for additional services “without discretion” or “unavoidably make the provision of existing services more costly.” In our office’s view, the mandate must have been created after 1978‑79 to qualify as an exclusion. Otherwise, the cost of that mandate would have been included in the base year’s limit.

- Qualified Capital Outlay Projects. The Constitution allows expenditures on capital outlay projects to be excluded from appropriations subject to the limit. Statute defines this as: “an appropriation for a fixed asset (including land and construction) with a useful life of 10 or more years and a value which equals or exceeds one hundred thousand dollars ($100,000).”

- Certain Emergency Spending. The Constitution also allows expenditures on emergencies to be excluded from appropriations subject to the limit. However, those expenditures must meet three specific conditions. The spending must be: (1) related to an emergency declaration by the Governor, (2) approved by two‑thirds vote, and (3) dedicated to an account for expenditures relating to that emergency.

Determine the Room

Third, the state compares the limit (calculated in step 1) to appropriations subject to the limit (calculated in step 2) to determine the difference. If appropriations subject to the limit are less than the limit, the state has room under the SAL. If appropriations subject to the limit exceed the limit (on net) over any two‑year period, there are excess revenues. The Constitution requires that these excess revenues either be:

- Appropriated for purposes exempt from the SAL.

- Split between additional school and community college district spending and taxpayer rebates.

How the Limits Work for Other Entities

Proposition 4 not only created an appropriations limit for the state, but also for most types of local government entities, including: counties, cities, special districts, and local educational agencies. This section describes how the appropriations limits work for these other entities.

School and Community College Districts

District SAL Calculations. State statutes detail the process by which districts administer their limits. (All school districts, county offices of education, and community college districts have local appropriation limits. Throughout this section we use the term “district” to refer to these entities.) The key steps are:

- Determine Base‑Year Appropriations Subject to Limit. Like the state, districts calculated their appropriations subject to the limit for the base year of 1978‑79. This required districts to determine proceeds of taxes, including their local property tax collections and subventions they received from the state, in that year. Like the state, districts determined their appropriations subject to the limit, less exclusions such as debt service. As implemented by the Legislature, districts counted a share of state funding at the district level, with remaining state funds, including funds for categorical programs, counted at the state level.

- Grow Appropriations Limit. Like the state, districts grow their prior‑year limits to establish their current‑year limits. Specifically, each district adjusts its prior‑year limit for (1) statewide growth in per capita personal income, and (2) changes to its student population. School districts measure their student population using average daily attendance, whereas community colleges use full‑time‑equivalent enrollment.

- Determine Appropriations Subject to Limit. After a district establishes its limit, it follows several steps to determine how much of its revenue from proceeds of taxes to count toward its limit. For most districts, proceeds of taxes is the sum of their share of the local property tax, parcel taxes, interest on investments, and general purpose state funding (for example, the Local Control Funding Formula for school districts or the apportionment formula for community colleges). The funding districts receive through categorical programs counts toward the state’s limit and is not part of the district calculation. Similar to the state, districts can exclude expenditures related to meeting federal mandates or court orders.

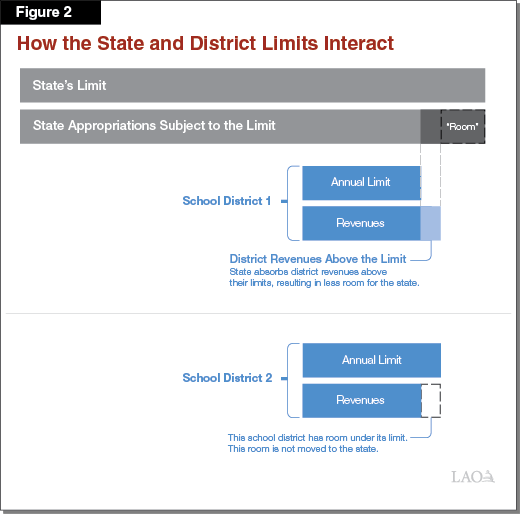

Funding That Cannot Be Counted Toward District Limits Is Counted at the State Level. In most cases, districts have greater proceeds of taxes than they are able to count toward their local limits. The portion of funding (whether from the state or property taxes) that cannot be counted toward district limits is counted using the state’s limit. The state has two ways to allow districts to spend above their limits. Either the state transfers some of its own limit to districts or it absorbs some of the district’s excess appropriations and counts those at the state level. Either mechanism allows the districts to spend above their limits and reduce the state’s room. Currently, there is about $17 billion in district revenues above their limits that is counted at the state level.

Some Districts Have Room Under Their Limits. Although most districts have proceeds of taxes in excess of their local limits, about 10 percent of districts are below their limits. We refer to this difference between the limit and appropriations subject to the limit as “room.” This situation can occur if a district had a historically high appropriations limit, or if a district has been experiencing relatively slow growth in funding. Collectively, districts have $5 billion in room.

Illustrative Example: How the State and District Limits Interact. Figure 2 shows the relationship between the state and district appropriations limits when the state absorbs districts’ excess appropriations. In most cases, when a district exceeds its appropriations limit (shown in the graphic as School District 1), the state increases its own appropriations subject to the limit, thereby reducing the state’s own room. Districts that are below their appropriations limits have room available, but that room is not transferred to the state (see School District 2 in the graphic).

Local Governments

Local Government SAL Calculations. The Constitution and state statutes detail the process by which local governments administer their limits. The key steps are:

- Determine Base‑Year Appropriations Subject to Limit. Like the state, local governments calculated their appropriations subject to the limit for the base year of 1978‑79. Local governments determined proceeds of taxes, including their local property tax collections, and subventions they received from the state.

- Grow Appropriations Limit. Like the state, local governments grow the prior year’s limit to establish the limit for the current year. The constitutional growth factors local governments can use are different and much more flexible than the state’s and districts’ factors. For example, counties can use any of the following population adjustments in calculating their limits: (1) the change in population within the county, (2) the change in population in the county and all counties that have contiguous borders with it, or (3) the change in population within the incorporated portion of the county.

- Determine Appropriations Subject to Limit. In general, for most local governments, proceeds of taxes is the sum of their local taxes, interest on investments, and state subventions. Like the state, local governments reduce their appropriations subject to the limit by exclusions, such as debt service and costs for complying with mandates.

Very Small Amount of State Funding to Local Governments Counted as Subventions. Each year, the state dedicates tens of billions of dollars in General Fund and special fund monies to local governments—particularly counties—for a variety of purposes. For example, the state dedicates funding to counties for the administration of several health and human services programs, like California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids and Medi‑Cal. The state also provides funding for a broad range of programmatic activities, for example, in criminal justice, housing and homelessness, and transportation. However, very little of this funding is counted toward local governments’ limits because funding must be unrestricted to meet the statutory definition of a subvention. Consequently, the state counts this funding towards its limit. The administration currently counts two major categories of funding to local governments as subventions: the vehicle license fee (VLF) and property tax backfills that the state has provided to locals.

Cities and Counties Have Substantial Room Available Under Their Limits. According to data from 2018‑19, only 6 counties (10 percent) and 68 cities (14 percent) have spending that is above 80 percent of their limits. A substantial majority of cities and counties (82 percent of counties and 70 percent of cities) have spending at or below 60 percent of their limits. Collectively, counties have nearly $100 billion while cities have $55 billion in collective room under their limits.

Why Is the SAL a Constraint for the State Now?

History of SAL

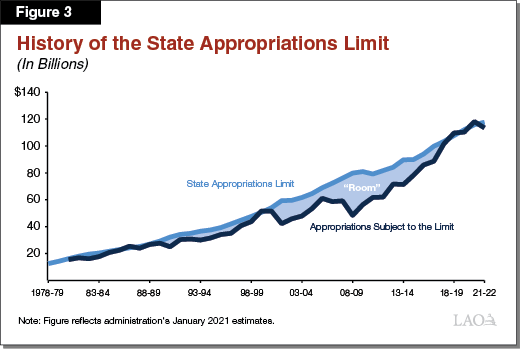

SAL Constrained State Spending in Mid‑1980s. Figure 3 shows historical calculations of the state’s limit and appropriations subject to the limit. Initially, the SAL had little effect on state budgeting. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, high inflation and slow revenue growth increased room under the limit. By the mid‑1980s, however, strong revenue growth quickly brought state appropriations closer to the limit. In 1986‑87, the state had excess revenues of $1.1 billion. Proposition 4 required the excess to be rebated to taxpayers.

Proposition 98 (1988) and Proposition 111 Made Changes to the SAL. In 1988, voters passed Proposition 98. Proposition 98 is the state’s constitutional minimum funding guarantee for schools and community colleges. Proposition 98 also amended the Constitution to require a portion of revenues above the limit—up to 4 percent of the minimum funding requirement—to be allocated to schools and community colleges. Two years later, Proposition 111 also made significant changes to the SAL. First, the measure changed the population and inflation growth factors in a way that created more room for state and local appropriations. Second, it required excess revenues to be determined over a two‑year period rather than in a single year, making it less likely to trigger taxpayer rebates and additional Proposition 98 spending. Third, the measure changed how excess revenues were to be distributed. Specifically, Proposition 111 required that half of the excess be allocated to additional district spending and half to taxpayer rebates. Lastly, Proposition 111 added additional categories of appropriations exclusions.

Room Under the Limit Has Diminished Over the Last Decade. The state’s appropriations subject to the limit fell substantially during the dot‑com bust in the early 2000s and again during the Great Recession due to the significant decline in state revenues during those downturns. Since around 2009, however, room under the limit has narrowed. As we discuss below, there are a variety of reasons for this, including: underlying growth in revenues (as growth in taxpayers’ incomes has outpaced economic growth) and the voters’ decisions to raise additional revenues, among others.

Significant Upward Revisions to Revenues Result in Diminished Room. When the 2020‑21 Budget Act was passed, it appeared the state had substantial—that is, tens of billions of dollars—in room under the limit. This room was due to the anticipated recession and associated revenue declines as a result of the pandemic. However, as of the January Governor’s budget, revenues have been tens of billions of dollars higher than anticipated. As a result of these significant upward revisions in revenue and associated appropriations subject to the limit, the state’s room has diminished considerably.

Dynamics Resulting in Diminished Room

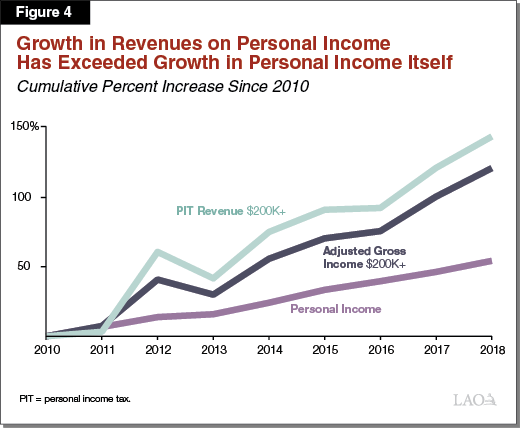

Growth in Personal Income Tax Revenue Has Exceeded Growth in Personal Income Itself. The most important factor in determining SAL growth is change in per capita personal income. In recent years, per capita personal income has grown more slowly than the state’s largest revenue source—the personal income tax. The two key reasons for this are: (1) the state personal income tax rates are higher for higher‑income earners, and (2) high‑income earners have experienced faster income growth than the general population. This is amplified by the fact that the state treats capital gains on sales of assets as taxable income, but capital gains are excluded from the measure of personal income used to calculate the SAL. Moreover, Californians with the highest incomes receive a disproportionate share of their income from capital gains. Consequently, capital gains revenues account for an outsized portion of personal income tax revenue growth, yet they do not increase the measure of personal income used to calculate SAL. Figure 4 shows how these factors result in differential growth rates between personal income, total income for those earning more than $200,000 annually, and personal income tax revenue from those high earners.

Policy Decisions Accelerated Underlying Trend. Underlying trends in personal income and asset prices would have resulted in faster growth in revenues than the SAL regardless of other tax policy decisions. Decisions to increase tax rates, however, have diminished the state’s room under the limit more quickly. In particular, Proposition 30 (2012) increased—and Proposition 55 (2016) extended—the top marginal rates for the personal income tax, thereby resulting in more state collections from capital gains. Other new tax levies, like the passage of Proposition 64 (2016)—which established state excise taxes on cannabis—further diminished room under the state’s limit.

School Spending Growing Faster Than School Limits. Over the past several years, Proposition 98 has required the state to provide relatively large increases in funding for schools and community colleges. In large part, these large increases were driven by the growth in tax revenues described earlier. For schools, general purpose funding grew by an average annual rate of 7.1 percent from 2013‑14 through 2019‑20. School district limits, by contrast, grew more slowly. Specifically, the growth in per capita personal income and student attendance (the two factors affecting district limits) averaged 3.1 percent per year over the period. Because most school districts have no room under their local limits, the state counted most of the increase in school funding over this period toward its own limit. Between 2013‑14 and 2019‑20, the amount of school funding counting toward the state’s limit increased from $4.9 billion to $17.3 billion. Community colleges also experienced notable increases in their apportionment funding over this period, although their increases tended to be smaller than those for school districts.

Population and Average Daily Attendance Have Been Flat or Declining. Trends in the state’s population—both for civilians and school‑aged children—also are determinants of the growth in the limit. Over the last decade, state population overall and of school‑aged children has been flat or declining. For example, school enrollment growth has averaged ‑0.1 percent over the last decade, compared to 2.26 percent in the 1990s. Overall state population growth has averaged 0.7 percent over the last decade, compared to 1.3 percent in the 1990s.

How Might the SAL Limit State Spending Growth?

In the Budget Year

State Has Diminished Room From 2018‑19 to 2021‑22. Based on the Governor’s January budget, state tax revenues already are close to the limit across the budget window. Specifically, the state is within a few billion dollars of the appropriations limit across 2018‑19 to 2021‑22. While the limit will change in May due to updated growth factors, increases in the state’s tax revenues that are not spent on excluded purposes will result in either diminished room or excess revenues.

SAL Will Be an Important Issue at May Revision. Since the Governor’s budget was released, tax collections for the General Fund have continued to exceed expectations. For example, as of March, tax collections are ahead of the Governor’s budget projections by more than $10 billion for 2020‑21. Due to limited room under the state’s limit, these strong collections suggest the SAL will be an important issue in crafting the budget. That said, there also are many other factors that will affect the SAL calculations at the May Revision. For example, the administration will update the calculation of the limit itself, which we expect to increase as a result of recently released data on personal income. In addition, the calculation will reflect updated estimates of excluded spending reflecting decisions made by the Governor in the May Revision budget proposal.

Federal Funding Excluded From the SAL. Federal funding, including the $26 billion in fiscal relief monies provided to California in the American Rescue Plan, does not count toward the SAL. However, the federal government prohibits the state from using these funds—directly or indirectly—to lower tax revenues. This could create some complications for the Legislature’s response to the SAL, which we discuss in more detail below.

Over the Longer Term

SAL Likely to Be a Major Issue Over the Next Few Years. While the SAL might be an important issue for the Legislature to consider as it crafts the 2021‑22 budget, our analysis suggests it will be an even more important factor in the state budget in the coming years. Figure 5 shows our projections of the likely room under the limit over the next few years. (The nearby box describes our methodology for arriving at these estimates in more detail.) Projections of the amount of room under the limit are highly uncertain, as shown by the wide range of possible outcomes in the figure. That said, under the vast majority of likely outcomes, we anticipate the state will have “negative room;” that is, the state would either need to reduce taxes or issue refunds to taxpayers and make additional payments to districts in these amounts. Within a few years, there is a good chance of a substantial amount of negative room. Specifically, by 2024‑25, the state is more likely than not to have negative room in excess of $10 billion. As a result, we anticipate the Legislature will need to make—potentially major—changes to the state budget in the coming years.

Methodology for Forecasting State Appropriations Limit (SAL) Room

The analysis described in this section uses historical data and forecasting techniques to account for a wide range of possible economic and policy scenarios, which drive different SAL outcomes. These models make a number of important assumptions. For example, we assume:

- The long‑term trend of higher income growth among high‑income Californians continues, resulting in faster growth in state revenues.

- The future level of new and expanded special fund taxes and fees will be similar to the past.

- The Legislature continues to dedicate spending toward excluded and non‑excluded purposes in similar proportions to historical trends.

- School district limits grow at roughly the same rate as the statewide limit.

Administrative Issues in the SAL

In this section, we describe a variety of administrative issues in the SAL that we recommend the Legislature direct the administration address.

Emergency Spending

Administration Is Not Counting State Spending on Emergencies as Exclusions. Over the past two years, the state has spent billions of dollars on the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) public health emergency. The administration currently estimates direct response costs related to COVID‑19 will be $15 billion across 2019‑20 through 2021‑22. In 2018‑19 through 2020‑21, the state also spent roughly close to $5 billion for wildfire response and remediation through the Disaster Response and Emergency Operations Account (DREOA). While a significant share of these costs are assumed to be reimbursed by the federal government—and therefore excluded from proceeds of taxes—the administration currently is not counting any of the state’s emergency spending as an exemption under the SAL.

Significant Share of State Spending on Recent Disasters Qualifies as Exemption. We think much of the state spending on these emergencies meets the criteria needed for an emergency exemption and should be excluded in the state’s SAL calculations. (Federal funding is already excluded from the SAL, so federal reimbursements to the state for emergency spending would not count as exclusions.) As mentioned above, certain conditions must exist for state spending on an emergency to qualify as an exemption, which exist in these cases:

- Governor Declared Emergency. First, to qualify as an exemption, spending on emergencies must be made in response to a declared emergency by the Governor. The Governor declared a state of emergency related to the COVID‑19 pandemic on March 4, 2020. This emergency is still ongoing. Since 2018, the Governor also declared states of emergency related to various wildfires. For example, the Governor declared a state of emergency related to the Camp wildfire on November 8, 2018, and related to the LNU Lightning Complex and other wildfires burning statewide on August 18, 2020.

- Appropriations Made From DREOA. Second, to qualify as an exemption, funds must be spent from a fund that is appropriated for the emergency and the appropriation must have been approved with a two‑thirds vote. The administration has made all of the above expenditures using DREOA, a fund that is continuously appropriated for state emergencies. The most recent authorizing legislation for DREOA, Chapter 2 of 2019 (AB 73, Committee on Budget), received a two‑thirds vote in both houses of the Legislature.

After accounting for federal reimbursements, exempting these appropriations—as provided for in the Constitution—could result in around $1 billion of additional room in each year in the budget window.

Vehicle License Fees

VLF Does Not Meet Statutory Definition of Subvention. Statute defines state subventions as monies that local governments can use for any purpose. When Proposition 4 was passed, VLF revenues—taxes levied on the registration of vehicles—were a flexible funding source that the state passed along to local governments, thus meeting this statutory definition. In the 1991 and 2011 realignments, the state dedicated these revenues to the new financial obligations of counties for realigned programs and responsibilities. However, the state did not stop counting VLF as a subvention under this policy change. Under current law, VLF does not meet the statutory definition of a subvention and should not be counted as such. Changing the treatment of VLF in the SAL calculations would result in diminished room of about $3 billion annually.

School and Community College Districts Exclusions

State Limit Affected by District Estimates of Excludable Appropriations. One aspect of districts’ calculation of particular importance to the state is the amount of spending districts attribute to federal and court mandates enacted after 1978‑79. This is important because the amount a district spends on these mandates does not count toward the limit of either the district or the state (if the district is over its limit). According to the latest available data, districts identified about $650 million in mandated spending. Based on our recent review, we think the actual amount could be at least several hundred million dollars higher, which could reduce the amount of spending shifted from districts to the state by a similar amount. Below, we describe the two areas where we think additional expenditures could be excluded.

Medicare Payroll Taxes. Federal law has required all schools and community colleges to participate in the Medicare program since 1986. Similar to private employers, the law requires districts to pay a tax equal to 1.45 percent of payroll. We found that nearly all of the $650 million in mandated expenditures districts currently report are related to the Medicare payroll tax. About 10 percent of districts, however, currently do not account for this tax in the calculation of their local limits. Requiring all districts to account for this expenditure in their calculations would increase excluded appropriations by approximately $150 million.

Services for Students With Disabilities. The federal government provides a significant amount of funding for schools. As a condition of receiving some of these funds, the federal Individuals With Disabilities Education Act requires schools to identify students with disabilities and provide services and supports necessary for these students to obtain a public education. Federal law established most of the core requirements of this act prior to 1978‑79. Since that time, however, Congress periodically has amended the law to require schools to provide additional services. For example, in 1986, the federal government began requiring districts to provide certain services to infants and preschool children with disabilities. Other changes enacted after 1978‑79 range from giving parents more control over the services provided for their children to defining certain categories of disabilities more expansively. Currently, districts do not exclude these additional costs in the calculation of appropriations subject to their limits. The state does not currently require districts to track these incremental costs, but we estimate they would represent at least a couple hundred million dollars statewide.

Net Effect of Administrative Recommendations

Diminished Room Under the State’s Limit. Exempting emergency appropriations from the SAL—as provided for in the Constitution—could provide around $1 billion of room in each year in the budget window. In addition, scrutinizing school and community college district mandate spending likely would increase room under the state’s limit by several hundred million dollars per year. In contrast, however, counting the VLF against the state’s limit would reduce room by a few billion dollars per year. Overall, we anticipate addressing these administrative issues in the SAL would result in less room by a couple of billions dollars in each year in the budget window. As summarized in figure 6, we recommend the Legislature direct the administration to make these changes to their calculation of the limit as part of the final budget this year.

Figure 6

Summary of Recommended Administrative Issues

|

Issue |

Recommendation |

|

Emergency Spending |

|

|

Vehicle License Fees (VLF) |

|

|

School and Community College Districts Exclusions |

|

|

Medicare Payroll Taxes |

|

|

Services for Students With Disabilities |

|

|

DREOA = Disaster Response and Emergency Operations Account |

|

How Can the Legislature Respond?

In addition to addressing administrative issues, the Legislature faces decisions about how to respond to approaching the limit. Options range from reducing appropriations subject to the limit—which can be done in a variety of different ways—to asking the voters if they wish to make a change to the limit itself. This section describes those various options. (Because reserve deposits count as appropriations subject to the limit, unallocated state revenues automatically count against the state’s spending limit. Thus, the Legislature does not have the option of saving revenues in reserves as a means of responding. In contrast, however, we note that federal funding does not count toward the state’s appropriations limit. Consequently, the federal fiscal relief provided by the American Rescue Plan does not affect the SAL.) These options are not mutually exclusive. In fact, we anticipate the Legislature will need to pursue multiple options over the short and longer term.

Issue Tax Refunds and Allocate Excess Revenue to Schools

The first option in responding to SAL is for the Legislature to implement Section 2 of Article XIIIB. Specifically, the state could have excess revenues in one or more years in the current budget window or in future years. If the Legislature chooses this option, any excess revenues over two years would be equally divided between taxpayer rebates and education spending. Over time, these actions—rebates and education spending—could require structural changes to the budget if existing program costs grew faster than revenues available for appropriation. In practice, these changes could require significant reductions to nonschool program spending.

Increase Spending on Excluded Purposes

Second, the Legislature could dedicate excess revenues on excluded purposes. For some exclusions, like federal and court mandates, legislative decisions play little role in increasing or decreasing the excluded spending. But for two exclusions, subventions to local governments and spending on capital outlay projects, the Legislature can exercise some discretion. Under current law, new funding to local governments would have to be provided on a very flexible basis to count as a subvention. (Subventions to school districts would not increase the state’s room because most districts are already at their limits, meaning the additional funds would revert back to the state as described earlier.) The existing statutory definition of capital outlay, by contrast, is fairly broad. This means funding for some existing state priorities, like more spending on housing, likely would qualify. As with other options, however, pursuing more spending on excluded purposes over the long term might need to be paired with other budgetary changes, such as reductions to existing services due to cost growth.

Reduce Proceeds of Taxes and Spending

Third, the Legislature could preemptively reduce proceeds of taxes. This would automatically result in less spending on schools and community colleges and would require the Legislature to make corresponding reductions in other spending so that the budget remained balanced. The state has more flexibility to do this within the General Fund than it does for some special funds because some of those have voter‑directed purposes. However, the Legislature also could reduce special fund revenues and spending. Our analysis suggests the state likely would need to lower revenues (and, correspondingly, spending) by tens of billions of dollars over the next few years to avoid collecting excess revenues. However, as described in the box below, pursuing an option to preemptively reduce revenues also could mean the state would lose fiscal relief funds from the federal government.

The American Rescue Plan (ARP) and the State Appropriations Limit (SAL)

ARP Discourages States From Using Fiscal Relief Funds to Make Revenue Reductions. The state is expected to receive $26 billion in fiscal relief funds from the federal government in the ARP. Federal statute prohibits the state from using the funds to directly or indirectly offset a reduction in the net tax revenue of the state through a change in law, regulation, or administrative interpretation. This prohibition applies from March 3, 2021 to the last date on which the state expends the funds. (The state has until December 31, 2024 to use the funds.) As of this writing, we do not yet know how strictly the U.S. Department of the Treasury will interpret the statutory restrictions on these funds. A strict interpretation of the statute could mean the state would not be able to make revenue reductions using General Fund dollars without forgoing an equal amount of federal recovery funds.

How Does the ARP Affect SAL Decisions? We have two questions about how the ARP might affect legislative decision‑making around the SAL. If the state collects excess tax revenues and issues tax refunds, would the federal government require the state to return a like amount of fiscal relief funds? Given that the SAL existed in the State Constitution prior to March 3, 2021, we think the state has a strong argument that it should not be required to return federal funds. However, if the state proactively reduces proceeds of taxes, would the federal government require the state to return a like amount of fiscal relief funds? We are not sure how the federal government would interpret the rules, but in this case, it seems more likely the state would have to forgo some federal fiscal relief. If this is the case, taking preemptive action to address the limit—for example by reducing taxes and spending—would double the effect on the state budget. That is, each $1 in reduced revenue would reduce state resources by $2.

Make Statutory Changes to the SAL

The fourth option is to make statutory changes to the SAL that give the state more room, but are consistent with the constitutional provisions and voters’ intent in Proposition 4. The options described below could collectively result in as much as $15 billion in additional room. Over the longer term, however, the state could still run out of room. As our analysis in Figure 5 indicated, there is about a 60 percent chance the state will have more than $15 billion in annual excess revenues by 2024‑25. As such, if the Legislature pursued these statutory changes, other actions—either implementing the provisions of Article XIIIB or otherwise—still could be required.

Shift Room Under District Limits to State. Current law provides for the state to shift some of its limit to any district that would otherwise exceed its local limit. This shift, however, only occurs in one direction—from the state to districts. We think the Legislature could amend the law to provide for shifts in the opposite direction. Specifically, the state could require districts to reduce their limits by the amount of any unused room, and increase its own limit by a corresponding amount. The latest data suggest that the 10 percent of districts with unused room have approximately $5 billion in room available. If the state were to adopt this approach, it could continue allowing districts to shift some of the state’s limit whenever they exceed their local limits. Allowing shifts to occur in both directions would increase flexibility for the state while still adhering to the principals of Proposition 4 by maintaining the same aggregate appropriations limit across districts and the state. Moreover, this would not introduce new constraints on district budgets.

Redefine Local Government Subventions. The state could consider amending statute to redefine the term subvention, and count more appropriations at the local, instead of state, level. Such a change would better reflect the dramatic changes in the state‑local relationship that have occurred since 1980. As a result of the 1991 and 2011 realignments, for example, the state now provides local governments with a revenue source for their share of certain program costs, whereas the state and local governments used to share in these costs. (We describe these changes in the box below. For more information about realignment see: Rethinking the 1991 Realignment and 2011 Realignment: Addressing Issues to Promote Its Long‑Term Success.)

State‑Local Relationship Has Changed Since 1978

Counties administer many programs on behalf of the state, including most health and human services programs. Historically, counties were responsible for some of the costs of these programs and used local revenue to pay those costs. After Proposition 13 (1978)—the landmark decision by voters to limit property taxes—local governments’ property tax revenues dropped by roughly 60 percent. In response, the state provided a “bailout” to partially backfill local governments’ revenue losses. For counties, this backfill developed into an ongoing change in the state‑county fiscal partnership.

Today, the state provides dedicated revenue streams to counties to pay for their share of costs for “realigned” programs. Realigned programs are those programs administered at the local level but whose fiscal responsibility is shared between the state and counties (and in some cases, federal government). The state provides dedicated revenues—about $14 billion—to counties for these programs due to their limited ability to raise revenue and due to other provisions of Proposition 4 (1979), which require the state to reimburse state‑imposed local requirements. Within limits, counties have discretion over how to use realignment revenues to meet program needs and requirements.

Updating the definition of subvention to account for these structural changes would be consistent with principles of the state‑local relationship in realignment. Specifically, counting realignment revenues at the local level would count the appropriations at the level of government making many of the decisions about that spending. Further, counting these revenues at the local level would maintain the spirit of Proposition 4. The aim of that measure was to keep government appropriations, at all levels of government, below the adjusted 1978‑79 level. This change would still adhere to that basic principal, but would count some spending within local government limits, instead of the state’s limit.

The Legislature would face choices in implementing this statutory change. One option would be to redefine subventions as any appropriation to local governments for programs over which local governments have fiscal responsibility. Another option would be to center the definition on which entity of government has more policy responsibility for the program. If the state made the change using a fiscal definition, it could result in the state counting up to $10 billion in additional spending as subventions, mainly to county governments. Using a policy‑driven definition, the amount of new subventions would be lower.

This policy change largely would affect counties, but would be unlikely to result in very many—or any—counties exceeding their limits. Collectively, counties have about $100 billion in unused room and, as noted earlier, very few counties are close to their limits. However, the state also could also structure this policy to ensure it does not results in a local government exceeding its limit, for example, by counting local government revenues in excess of their limits at the state level. This would be similar to the procedure the state currently has in place for school districts.

Go to the Voters

Fifth, the Legislature could choose to request changes to the state’s limit from the voters. There are many different ways by which the Legislature could request this change. We discuss some of those options here.

Request Temporary Increase in the State’s Limit. The Constitution allows the state’s voters to change the appropriations limit for any entity of government for a period of up to four years. Under this rule, the Legislature could request the voters provide a temporary increase in the appropriations limit. This would give the state time to pursue longer‑term and more structural changes to the state’s budget (such as reductions to taxes and spending) in the meantime.

Request Change to School and Community College Districts’ Limits. Under the provisions of Proposition 98, the state is required to spend minimum amounts on schools each year. As noted earlier, largely due to faster growth in revenues, growth in district spending (under Proposition 98) has outpaced the limit on school district spending (under the provisions of Proposition 4). This trend has reduced the room available under the state’s limit because any school spending that exceeds district limits counts at the state level. To maintain the goal of Proposition 98 to provide a certain amount of funding to schools—without crowding out other state spending—the Legislature could consider asking the voters to modify districts’ limits. There are different ways to modify districts’ limits depending on the Legislature’s preferences. For instance, asking for a change to the calculation of districts’ limits—like the changes made to city, county, and special district limits under Proposition 111—would maintain spending limits for schools while providing greater flexibility in the calculation of those limits.

Request Change in When Reserves Are Counted Toward the Limit. Another change the Legislature could request voters make is with respect to when reserve deposits and withdrawals are counted toward the limit. Proposition 2 (2014) required the state to set aside more funds in reserves. Under Proposition 4, reserve deposits are counted in the year they are made (instead of the year they are withdrawn). While Proposition 2 requires the state to set aside minimum amounts in reserve each year, Proposition 4 limits reserve deposits like other state appropriations, creating a tension between these two constitutional calculations. Instead, the voters could change the limit calculation so that reserves count toward the limit in the year they are withdrawn.

Request More Fundamental Change. The voters are permitted to make any changes to the SAL that they deem appropriate. Instead of a four‑year increase or other narrower changes, the Legislature could request more far‑reaching or permanent changes, increases, or modifications to the SAL.

Constructing a Plan

We anticipate the Legislature will need to take action related to the SAL this year and over the next few years. As such, we recommend the Legislature construct a short‑ and long‑term plan for how it wishes to respond. On the one hand, the Legislature may wish to issue refunds and provide additional funding to schools. This solution might not be sustainable over the long term, however. As existing program costs increase, revenues available for appropriation could be insufficient to meet current service levels. Consequently, changes to the state’s revenues and expenditures would be required. On the other hand, should the Legislature wish to pursue alternative options, statutory changes are unlikely to be sufficient to avoid reaching the limit in the next few years. In that case, considering placing a measure before the voters could be needed.

To aid the Legislature in constructing its plan, Figure 7 summarizes the options presented in this report, when each option could take effect, and our estimate of the potential magnitude of each potential change.

Figure 7

Consider Timing and Amounts of Various Policy Options

|

Policy Option |

Timing |

Amount |

|

Issue tax refunds and allocate excess revenues to schools |

Immediate. Legislature can pursue immediately. However, significant, ongoing refunds and school allocations could require more structural changes to the state budget. |

Tens of billions |

|

Increase spending on excluded purposes |

Immediate. The Legislature can increase spending on excluded purposes in the 2021‑22 budget. |

Billions |

|

Reduce proceeds of taxes and spending |

Depends. The Legislature can pursue these reductions immediately, but major reductions to state services would take time to implement. |

Tens of billions |

|

Make statutory changes to the SAL |

||

|

Immediate. Legislature could implement in budget trailer bill legislation in 2021‑22. |

Five billion |

|

A Year or So. The Legislature could enact the statute in budget trailer bill legislation, but the policy change would take the administration time to implement. |

Up to ten billion |

|

Go to the voters |

||

|

A Year or More. The Legislature could place a measure on the ballot to request a change. |

Unlimited |

|

Tens of billions |

|

|

A couple billion |

|

|

Unlimited |