LAO Contact

Appendix Tables

Select proposals by policy area.

Criminal Justice: Discretionary Spending Proposals in the 2021‑22 May Revision

Health: Discretionary Spending Proposals in the 2021‑22 May Revision

Higher Education: Discretionary Spending Proposals in the 2021‑22 May Revision

Housing and Homelessness: Discretionary Spending Proposals in the 2021‑22 May Revision

Human Services: Discretionary Spending Proposals in the 2021‑22 May Revision

Other: Discretionary Spending Proposals in the 2021‑22 May Revision

Resources and Environment: Discretionary Spending in the 2021‑22 May Revision

Transportation: Discretionary Spending Proposals in the 2021‑22 May Revision

May 17, 2021

The 2021-22 Budget

Initial Comments on the Governor’s

May Revision

Key Takeaways

We Estimate the State Has a $38 Billion Surplus to Allocate. We estimate the state has $38 billion in discretionary state funds to allocate in the 2021‑22 budget process, an estimate that is different than the Governor’s figure—$76 billion. The differences in our estimates stem from our differing definitions. The Governor’s estimate includes constitutionally required spending on schools and community colleges, reserves, and debt payments. We do not consider these spending amounts part of the surplus because they must be allocated to specified purposes.

In Contrast to the Governor, Recommend Legislature Restore Budget Resilience. Despite a historic surge in revenues, the Governor continues to rely on budget tools from last year. Specifically, he uses $12 billion in reserve withdrawals and borrowing to increase spending. The state will need these tools to respond to future challenges, when federal assistance might not be as significant. We urge the Legislature not to take a step back from its track record of prudent budget management.

State Appropriations Limit (SAL) Is Important Issue in May Revision. The Governor’s May Revision estimates the state will collect $16 billion in revenues in excess of the SAL this year. However, the ultimate amount of a potential excess will depend on decisions by the Legislature. Ultimately while the SAL will be an important consideration in this year’s budget process, the Legislature has substantial discretion in how to meet the constitutional requirements.

Trade-Off Between Addressing Many Issues and Making More Significant Inroads on a Smaller Subset. The May Revision includes roughly 400 new proposals. While the surplus is large enough to make significant inroads in addressing a few key policy priorities, it is unlikely sufficient to do so across the number of issues contemplated in the May Revision. If the Legislature preferred to make surer substantial progress in a few key areas, it could allocate the surplus in a more targeted manner that reflect its top priorities.

Consider Withholding Some Decisions. The surplus, in combination with the federal fiscal recovery funds, represents resources equal to about half of pre-pandemic General Fund budgets. Departments’ capacity to allocate this funding in a timely and effective manner likely will be significantly constrained. More importantly, the Legislature’s time to deliberate over choices made in this budget is extremely limited. We recommend the Legislature delay some of those decisions and offer options for doing so.

Introduction

On May 14, 2021, Governor Newsom presented a revised state budget proposal to the Legislature. (This annual proposed revised budget is called the “May Revision.”) In this post, we provide a summary of the Governor’s revised budget, focusing on the overall condition and structure of the state General Fund—the budget’s main operating account. In the coming days, we will analyze the plan in more detail and provide additional comments in hearing testimony and online.

We begin with an overview of the condition of the General Fund under the administration’s estimates and proposals. We then describe the major spending-related decisions made by the Governor in allocating budget resources. Due to the additional complexity in this year’s budget, this discussion is not limited to the General Fund surplus, but also covers flexible federal funding to the state and the State Appropriations Limit (SAL). Next, we describe the structure of the General Fund under the Governor’s May Revision. We conclude with our initial comments on this budget package. (We also include links to Appendix tables at the end of this post and the top left of this page. These appendix tables itemize select proposals by policy area based on our understanding at this time.)

The information presented in this post is based on our best understanding of administration proposals as of Saturday, May 15, 2021. In many areas of the budget, our understanding of the administration’s proposals will continue to evolve as we receive more information. We only plan to update this post for very significant changes (that is, those greater than $500 million).

General Fund Condition

Excluding Policy Choices, Revenues Higher by $51 Billion Compared to Governor’s Budget. Reflecting very strong cash collections in recent months, the May Revision adjusts 2020‑21 revenues (and transfers) up by $26.8 billion to $182 billion. This represents a 27 percent increase over 2019‑20, the largest single year increase in over four decades. Much of these revenue gains carry over into the budget year, with 2021‑21 revenues being adjusted up $24.4 billion to $179 billion. For additional discussion on revenues, see our related post The 2021‑22 Budget: May Revenue Outlook.

Constitutionally Required Spending Higher by $16 Billion. The constitution requires the state to spend minimum annual amounts on schools and community colleges (under Proposition 98) and budget reserves and debt payments (under Proposition 2). Mainly as a result of higher revenues, relative to January, constitutionally required spending is higher by nearly $16 billion across the budget window.

Other Major Adjustments Reduce Costs by $3 Billion. In addition to revenues and constitutional requirements, other budgetary costs are, on net, lower by $3 billion compared to January. This relatively small number obscures many billions of dollars in budgetary changes. For example, relative to the Governor’s budget, the Legislature enacted about $6.4 billion in spending increases and revenue reductions through early action. Partially offsetting this increase, baseline costs associated with the state’s major safety net programs are lower by $3.7 billion.

Total Reserves Would Reach Nearly $20 Billion Under Governor’s May Revision. Under the administration’s estimates and proposals, total reserves would reach $19.8 billion in 2021‑22. (This total differs somewhat from the administration’s estimate of total reserves because we exclude the dedicated reserve for schools and community colleges, which we do not consider part of General Fund reserves.) Figure 1 shows the General Fund condition, including total reserves, under the Governor’s May Revision.

Figure 1

General Fund Condition Summary

(In Millions)

|

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

|

|

Prior‑year fund balance |

$11,442 |

$5,657 |

$27,434 |

|

Revenues and transfers |

140,400 |

187,020 |

175,921 |

|

Expenditures |

146,185 |

165,243 |

196,795 |

|

Ending fund balance |

$5,657 |

$27,434 |

$6,561 |

|

Encumbrances |

3,175 |

3,175 |

3,175 |

|

SFEU balance |

$2,482 |

$24,259 |

$3,386 |

|

Reserves |

|||

|

BSA |

$17,350 |

$12,494 |

$15,939 |

|

SFEU |

2,482 |

24,259 |

3,386 |

|

Safety net |

900 |

450 |

450 |

|

Total Reserves |

$20,732 |

$37,203 |

$19,775 |

|

SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties and BSA = Budget Stabilization Account. |

|||

Major Spending Choices

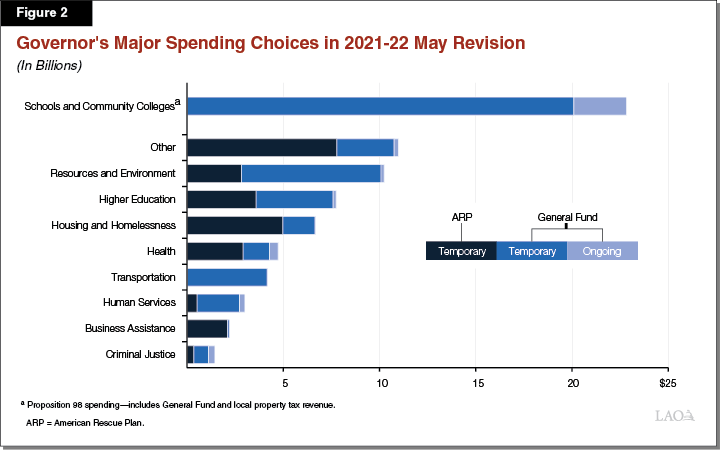

Figure 2 displays the major budgetary decisions that the Governor made in allocating state and federal money, totaling $85 billion. It includes (1) the General Fund surplus, (2) school and community college spending, (3) the American Rescue Plan (ARP) fiscal relief funds, and (4) ARP capital projects funds. The remainder of this section discusses each of these funding amounts in turn. As the figure shows, schools and community colleges would receive the largest spending allocations. The major components of the other category are $5.5 billion for broadband, $1.1 billion to replenish the state Unemployment Insurance Trust Fund, and $305 million for the Employment Development Department to more quickly address workload.

General Fund Surplus

We estimate the Governor had a $38 billion General Fund surplus to allocate in the 2021 May Revision. This surplus reflects the factors described above: higher revenues, higher constitutional spending, and net lower other spending. This section describes that surplus in more detail, with a focus on the spending choices the Governor made in allocating it.

What Is the General Fund Surplus? The Governor’s May Revision is the starting point for legislative deliberation. Ultimately, the Legislature will make its own determination about how to allocate available funds in the budget. One of the goals of this post is to estimate how much capacity the budget has to make those allocations under the Governor’s estimates of revenues. We answer this question by assessing which of the Governor’s proposals are “discretionary.” We define discretionary spending to mean spending, reserve deposits, debt payments, and tax reductions not already authorized or required under current law. (Our definition of discretionary excludes the cost to maintain current state services, such as base increases for the universities and employee compensation.)

Why Does This Figure Differ From the Governor’s Estimate? The Governor and administration have cited a surplus estimate of about $76 billion, which is different than our estimate. The primary source of this difference is that the Governor’s estimate of the surplus includes constitutionally required spending, whereas our estimate excludes it. For example, the Governor counts $27 billion in constitutionally required spending on schools and community colleges, nearly $8 billion in required reserve deposits, and $3 billion in required debt payments in his calculation of the surplus. After excluding these amounts, our surplus estimates are nearly the same.

How Can These Monies Be Used? In a normal budget year, General Fund surplus monies are available to use for any public purposes. This is not necessarily the case in this May Revision. That is because the SAL, which limits how the state can use revenues that exceed a specified threshold, is salient to the state budget process this year. As a result, the administration allocates $23 billion towards purposes that meet SAL requirements. The remaining surplus is used more flexibly. The nearby box explains these dynamics in more detail.

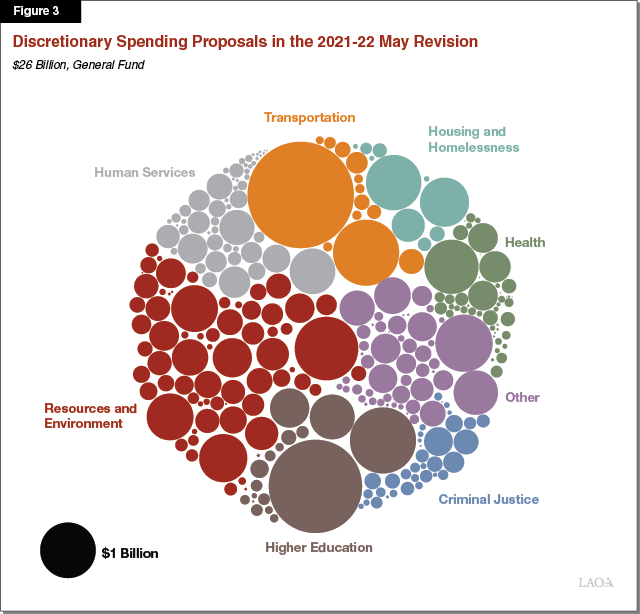

The Governor Proposes Allocating $26 Billion in Surplus Funds to Spending. Using the $38 billion surplus, the Governor proposes roughly four hundred spending-related proposals, which would cost $26 billion. (We describe how the Governor allocates the remainder of the surplus in the Budget Structure section.) Less than one-quarter of these proposals are unchanged from the Governor’s budget. The remaining three-quarters are either modified proposals or entirely new proposals in the May Revision. Figure 3 shows these proposals by program area.

The State Appropriations Limit (SAL)

SAL Limits Use of Surplus. Each year, the state compares the appropriations limit to appropriations subject to the limit. If appropriations subject to the limit exceed the limit (on net) over any two-year period, there are excess revenues. The Legislature can use excess revenues in three ways: (1) appropriate more money for purposes excluded from the SAL (under the Governor’s proposal, the common new spending for this purpose is capital outlay), (2) split the excess between additional school and community college district spending and taxpayer rebates, or (3) lower tax revenues. For more information on the SAL, please see our recent report: The State Appropriations Limit.

How Does the Governor Use the Surplus for SAL-Related Purposes? Under the administration’s estimates and proposals, $23 billion of the surplus is split between two SAL-related purposes:

-

$15 Billion in Discretionary Spending on Excluded Purposes. The Governor’s General Fund discretionary proposals include $15 billion in discretionary SAL exclusions. These exclusions are entirely proposals for capital outlay projects of various kinds.

-

$8 Billion Dedicated to Tax Rebates. After making administrative changes and proposing excluded spending, the administrations estimates indicate the state would have excess revenues of $16.2 billion across 20202‑21 and 2021‑22. The Governor allocates half of these excess revenues—$8.1 billion—to taxpayer rebates for taxpayers with incomes less than $75,000. The administration does not allocate the remaining half to schools and community colleges in this budget. (The State Constitution allows the state two years to make the payments.) The estimate of the amount owed to K-14 education could change substantially in the coming years as a result of changes in revenue estimates and legislative decisions.

Governor Includes Administrative and Proposed Statutory Changes. The May Revision includes three noteworthy administrative or statutory changes to the SAL. These three changes increase room under the SAL. First, the administration will stop counting vehicle registration fees as proceeds of taxes. Second, the administration is making an administrative correction of its treatment of school-related deferrals. Third, consistent with an option we presented in our recent report, the administration is proposing trailer bill language to absorb school districts’ room. We think all of these changes are reasonable.

ARP Flexible Funding

What Are the ARP Flexible Funds? The ARP included $350 billion in funding to state and local governments for fiscal recovery in the Coronavirus State Fiscal Recovery Fund. Of this total, California’s state government will receive about $27 billion. In addition, California will receive $550 million in Coronavirus Capital Projects Fund from the ARP, which also are available to the state on a more flexible basis.

How Can These Monies Be Used? The state is permitted to use the fiscal relief funds: (1) to respond to the public health emergency or negative economic impacts associated with the emergency; (2) to support essential work; (3) to backfill a reduction in revenue that has occurred since 2018‑19; or (4) for water, sewer, or broadband infrastructure. The funds will be transferred soon, but the state has until December 31, 2024 to use the funds. The U.S. Department of the Treasury recently released detailed guidance with more detail on how these funds can be used.

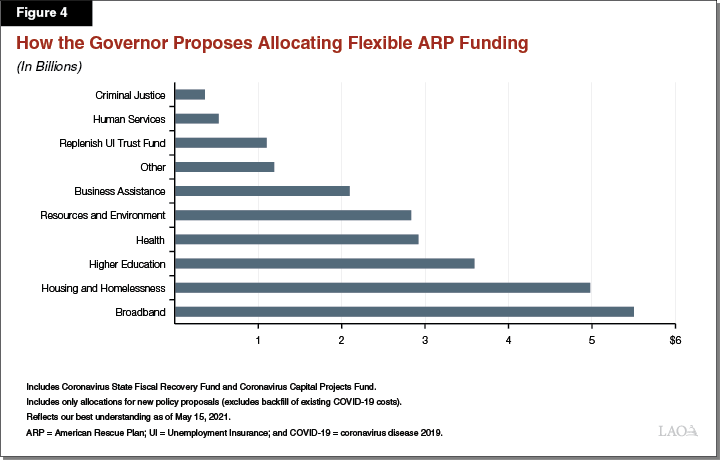

How the Governor Proposes Allocating the ARP Funds. Figure 4 shows how the Governor proposes allocating the flexible funds in the ARP by program area. (In addition to the amounts shown, the Governor proposes using $1.5 billion of ARP fiscal relief funds to pay for the sate share of direct coronavirus disease 2019 expenditures, resulting in lower General Fund costs by that amount.) This figure reflects our best understanding of the ARP at this time. However, we are still receiving information from the administration on the uses of ARP funds. The single largest proposal using ARP monies is $5.5 billion for broadband access, affordability, and infrastructure. In addition, the Governor proposes allocating nearly $5 billion to housing and homelessness and $3.6 billion to higher education. However, the administration also proposes control section language that would give the administration significant flexibility to reallocate these funds.

School and Community Colleges

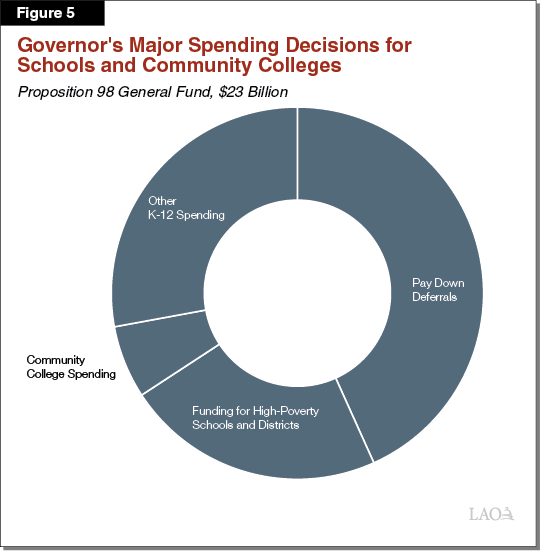

Governor’s Major Spending Choices for Schools and Community Colleges. The State Constitution sets a minimum annual funding requirement for schools and community colleges. After setting aside early actions, the May Revision includes nearly $23 billion in spending proposals to provide the constitutionally required funding increases to schools and community colleges. As shown in Figure 5, the Governor proposes allocating nearly $10 billion of this total to pay down deferred payments from previous years, $5 billion (including $2.1 billion ongoing) for high-poverty schools and districts, nearly $1.4 billion for community colleges, and the remainder (roughly $6 billion) for other K-12 spending.

Budget Structure

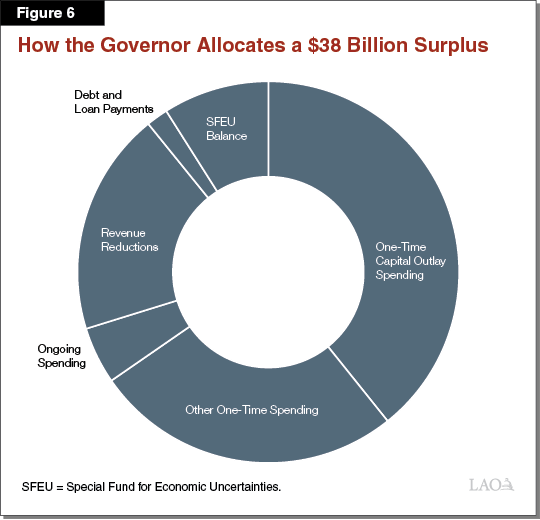

This section and figure 6 describe the allocation of the $38 billion General Fund surplus, which excludes spending on schools and community colleges. The Governor allocates: $25 billion to one-time or temporary spending, including nearly $15 billion for capital outlay; $7 billion to revenue-related reductions; $3.4 billion to the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU) balance; and nearly $2 billion to ongoing spending increases, although these costs would grow substantially over time. (In addition, the Constitution requires the state to set aside $11 billion for reserves and debt payments. We also describe those below.)

One-Time Spending

The Governor proposes spending $25 billion of General Fund surplus monies on a one-time or temporary basis. The majority of these one-time proposals ($15 billion) meet the definition of capital outlay for the purposes of the SAL and are excludable.

Governor Proposes $15 Billion in Spending on Capital Outlay. The Governor proposes allocating $15 billion of General Fund to capital outlay. (To define capital outlay, due to the importance of the SAL in state budgeting this year, we use the more expansive definition found in Government Code 7914, rather than the traditional budgetary definition.) For example, the Governor’s General Fund proposals include $2.6 billion for transit and rail projects, $2 billion for affordable college student housing, $550 million for the Homekey program, and $500 million for zero-emission vehicle fueling infrastructure. If the Legislature wants to make different decisions about this spending (without statutory changes or fund shifts), it can either: (1) use the funds to make tax rebates and additional payments to schools, (2) spend on other SAL-excluded purposes, or (3) use the funds to reduce taxes.

Governor Proposes $10 Billion in Spending on One-Time or Temporary Programmatic Activities. The Governor proposes spending $9.8 billion on a one-time or temporary basis for a variety of programmatic expansions that do not meet the definition of capital outlay. The largest proposals include $500 million for Golden State teacher grants and a $500 million endowment for learning-aligned employment.

Reserves and Debt

$11 Billion in Constitutional Reserve and Debt Requirements. Under the administration’s revenue estimates, the Constitution would require the state to deposit $7.6 billion into the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA) and spend an additional $3.4 billion to pay down debts. The BSA deposits would be required regardless of whether or not the state had made withdrawals from the BSA in 2020. That is, they are large because of revenue revisions, not due to restoring withdrawals made last year to address the anticipated budget problem.

Using Surplus, Governor Repays $700 Million in Loans and Proposes SFEU Balance of $3.4 Billion. In addition to fulfilling the constitutional requirements, the Governor dedicates about $700 million in discretionary resources to repay special fund loans and sets the balance of the SFEU at $3.4 billion for the end of 2021‑22. This is somewhat higher than the enacted balance of the SFEU from June 2020. Notably, however, the administration’s multiyear estimates include a negative SFEU balance of $6 billion in 2022‑23.

Despite Sizeable Surplus, Governor Maintains Borrowing and Reserve Withdrawals. The Legislature passed the 2020‑21 budget in the face of major uncertainty. While there was little precedent to work from, revenues were expected to fall sharply. The Legislature took $54 billion in actions to address that problem (for example, it withdrew funds from reserves, shifted costs, reduced spending, and increased revenues). However, under the administration’s estimates, General Fund tax revenues actually grew between 2019‑20 and 2020‑21 by 27 percent, the largest increase in four decades. While the Governor’s proposals this year eliminate most of the spending-related budget solutions, they still maintain significant budgetary borrowing and reserves withdrawals. Put another way, $12 billion of spending in the May Revision is attributable to reserve withdrawals and borrowing from 2020 (see Figure 7).

Figure 7

Governor Still Uses Budget Solutions Despite

Historic Revenue Growth

Budget Solutions From 2020 Maintained in 2021 May Revision

(In Billions)

|

Reserve Withdrawals |

|

|

Make Budget Stabilization Account withdrawal |

$7.8 |

|

Make Safety Net Reserve withdrawal |

0.5 |

|

Borrowing and Cost Shifts |

|

|

Shift pension costs |

$1.7 |

|

Special fund loans |

1.4 |

|

Convert capital financing to lease revenue bonds |

0.7 |

|

Make special fund transfers |

0.1 |

|

Total |

$12.1 |

|

Note: Excludes spending and revenue‑related budget solutions. |

|

Tax Reductions

Governor Proposes $7.1 Billion to Tax- and Revenue-Related Reductions. The most significant of these proposals is $8.1 billion in tax rebates to households with incomes of $75,000 or less. (As referenced in the box earlier, these payments would satisfy half of the constitutional requirement under the SAL.) Partially offsetting the cost of the rebates is additional revenue from a proposal for a new elective tax on certain businesses. This proposal gives certain business owners a new option for restructuring their state income taxes that would enable them to reduce their federal income taxes but result in somewhat increased state tax liability.

Ongoing Spending

Governor Proposes $1.8 Billion in Spending on Ongoing Programmatic Activities, With Significant Outyear Cost Increases. The Governor’s spending proposals also include $1.8 billion in ongoing discretionary spending. (We exclude funding provided to maintain the cost of current state services, such as base increases for the universities and employee compensation, from discretionary spending. These baseline cost increases increase ongoing spending by roughly $2.3 billion.) Some of the largest of these include the Governor’s proposals to increase child care slots, expand full-scope Medi-Cal coverage to all adults aged 60 and older and to implement a set of reforms to Medi-Cal called California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal (CalAIM). However, because some of these ongoing proposals are phased in over a multiyear period, we estimate the cost at full implementation of all of these proposals is $3.7 billion in 2024‑25. In addition, by 2024‑25, under the May Revision, the state would spend $2.7 billion ongoing for Transitional Kindergarten. (Under the Governor’s proposal, spending on schools and community colleges under Proposition 98 would increase to accommodate this program expansion.)

LAO Comments

Budget Structure

In Contrast to the Governor, Recommend Legislature Restore Budget Resilience. Despite a historic surge in revenues, the Governor continues to make use of nearly $12 billion in budget tools—reserve withdrawals and borrowing—to increase spending. While the state continues to respond to the pandemic, using tools designed for a budget crisis to support state spending at this time is shortsighted and inadvisable. The state will need these tools to respond to future challenges when federal assistance may not be as significant. For instance, in the next recession, the state is likely to have sizeable declines in revenues. To avoid reductions to safety net programs that support Californians when economic hardship is most acute, budget reserves are critical. For instance, in last year’s budget process, when the state anticipated a historic budget problem, cuts to safety net programs were largely avoided because of the state’s significant reserves. In recent years, the Legislature has made careful and considered budget actions, which have put the state on better fiscal footing. We urge the Legislature not to take a step back from its track record of prudent budget management.

Budget Decisions Are Multidimensional Due to SAL. Although the state budget is always complicated, budget decisions will be even more complex this year. The main reason for this is the SAL, which places significant restrictions on how the Legislature can use the surplus. The Legislature, however, can make a variety of different decisions, which will affect whether tax rebates or future tax cuts are necessary. Moreover, the Legislature could make additional changes to the calculation of the SAL as we describe in our recent report. Ultimately while the SAL is an important consideration in this year’s budget process, the Legislature has substantial discretion in how to meet the constitutional requirements.

Spending Choices

Budget Includes Various Proposals to Address Pandemic and Problems Exacerbated by Crisis. Appropriately given the dramatic and widespread impacts of the pandemic, many of the Governor’s larger proposals seek to mitigate either the pandemic’s direct impacts or problems exposed by the health and economic crisis. The Governor’s homelessness proposal would allocate significant resources to a long-standing problem that has been heightened by the pandemic. The state also plays a foundational role in enabling economic growth by maintaining well-functioning infrastructure, transit, and higher education. The May Revision includes many proposals in these areas. A notable number of May Revision proposals provide augmentations to new programs, however, rather than making significant increases to existing safety net programs—like California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) and Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Payment (SSI/SSP)—or rate increases in programs like the Department of Developmental Services.

Trade-Off Between Addressing Many Issues and Making More Significant Inroads on a Smaller Subset. The May Revision aims to address many problems. While many of these problems are well known, their solutions—particularly coming out of a pandemic—are less understood. For example, whether the administration’s workforce proposals will attract workers to retrain remains to be seen. Moreoever, many of the Governor’s proposals touch on similar issues, but the ways in which they would interact remain unclear. As the Legislature crafts its budget, we recommend considering whether to spread funding across many disparate issues or to dedicate more substantial resources to a smaller set of problems for which the Legislature has greater assurance of success. While the surplus is large enough to make significant inroads in addressing a few key policy priorities, it is unlikely sufficient to do so across the number of issues contemplated in the May Revision. If the Legislature preferred to make surer substantial progress in a few key areas, it could allocate the surplus in a more targeted manner that reflects its top priorities.

State Has Limited Capacity for New Spending and Oversight. The surplus, in combination with the federal fiscal recovery funds, represents resources equal to about half of pre-pandemic General Fund budgets. This is an extraordinary amount of funding. Departments’ capacity to allocate this funding in a timely and effective manner likely will be significantly constrained. As a result, some funding could go out much more slowly than anticipated, particularly for new programs. Moreover, departments’ ability to oversee this new spending likely will be limited as well. While the administration proposes a relatively small new unit within the Department of Finance to oversee new federal spending, more robust mechanisms for both state and federal funding—administratively and legislatively—are warranted.

Consider Withholding Some Decisions. The administration proposes allocating almost all of the surplus and fiscal relief funds now. Given the constrained time line of the budget process, limited administrative capacity, and potential for future action at the federal level, we recommend the Legislature withhold decisions on some components of the May Revision. Delaying some spending decisions would give the Legislature more time to determine which solutions would be most effective and develop a detailed plan. For example, the Legislature could wait to allocate the federal fiscal relief funds until more is known about what supports and services are needed as more Californians return to work, federal relief winds down, and the pandemic ebbs. The Legislature also could implement other mechanisms as part of this budget to provide more opportunities for Legislative oversight and additional time to make allocation decisions. We describe these options in the nearby box.

Options for Improving Legislative Oversight

Should the Legislature want more time to deliberate on the specifics of its budget package and identify opportunities for Legislative oversight, there are various options to consider. The Legislature also could use multiple options simultaneously for any particular proposal to ensure effective planning and oversight.

-

Make Funding Contingent on Subsequent Legislation. While the Legislature will need to appropriate the funding as part of the budget act, the Legislature can make allocation of funds dependent on subsequent trailer bill legislation that could be passed later this year. Doing so would give the Legislature additional time to ensure funds are allocated consistently with the Legislature’s goals.

-

Allocate Funding Over Multiple Years. The May Revision includes numerous proposals involving large, near-term expenditures. The Legislature alternatively could spread these allocations out longer. Doing so—in combination with subsequent legislation or setting milestones for progress—could provide more assurances that the funding is used effectively.

-

Include Reporting Requirements Before Releasing Funds. Rather than allocating all of the funding for a particular proposal at once, the Legislature could allocate some planning funding at the time of the budget act but make the remaining funds contingent on additional information from the department on how it would disperse the remainder. Also, the Legislature could allocate funding on a one-time or temporary basis before determining the appropriate amount of ongoing funding.

-

Delay Implementation. Similar to requiring additional information before releasing the funds, the Legislature could start full implementation of new programs in 2022‑23 (or later) and provide some funding in 2021‑22 to plan and build additional administrative capacity.

-

Make Funding Contingent on Legislative Notification. Often, the Legislature requires the administration to notify the Joint Legislative Budget Committee (JLBC) before allocating unanticipated funding midyear. The Legislature further could require notification of the JLBC before dispersing certain appropriations contained within the budget.

Appendix Tables

Select proposals by policy area.

Criminal Justice: Discretionary Spending Proposals in the 2021‑22 May Revision

Health: Discretionary Spending Proposals in the 2021‑22 May Revision

Higher Education: Discretionary Spending Proposals in the 2021‑22 May Revision

Housing and Homelessness: Discretionary Spending Proposals in the 2021‑22 May Revision

Human Services: Discretionary Spending Proposals in the 2021‑22 May Revision

Other: Discretionary Spending Proposals in the 2021‑22 May Revision

Resources and Environment: Discretionary Spending in the 2021‑22 May Revision

Transportation: Discretionary Spending Proposals in the 2021‑22 May Revision