LAO Contacts

- Mark Newton

- Overall Health Issues

- Ben Johnson

- Overall Medi-Cal Issues

- Covered California

- Sonja Petek

- Public Health

- Emergency Medical Services

- Health and Human Services Agency

- Corey Hashida

- Medi-Cal Issues

- Behavioral Health Issues

- State Hospitals

- Statewide Health Planning and Development

- Brian Metzker

- Technology Issues

October 22, 2021

The 2021-22 California Spending Plan

Health

- Health and Human Services Crosscutting Issues

- Medi-Cal

- Behavioral Health

- Department of State Hospitals (DSH)

- California Department of Public Health

- Emergency Medical Services Authority (EMSA)

- Covered California

- Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development

- Appendix: Major Actions—State Health Programs

Overview

The spending plan provides $33.7 billion General Fund for health programs. This is an increase of $6.7 billion, or 25 percent, compared to the revised 2020‑21 spending level, as shown in Figure 1. This year-over-year increase primarily is due to significant growth in projected General Fund spending in Medi-Cal. About two-thirds of the increase in General Fund Medi-Cal spending reflects technical budget adjustments (for example, adjustments due to projected caseload increases), while the remaining one-third reflects a large number of discretionary policy augmentations.

Figure 1

Major Health Programs and Departments—Spending Trends

General Fund (Dollars in Millions)

|

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

Change From |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

|||

|

Medi‑Cal—local assistance |

$21,480.3 |

$27,977.1 |

$6,497.0 |

30% |

|

Department of State Hospitals |

1,852.3 |

2,590.4 |

738.1 |

40 |

|

California Health Benefit Exchange (Covered California) |

83.0 |

20.0 |

‑63.0 |

‑76 |

|

DHCS—state administration |

251.1 |

311.4 |

60.2 |

24 |

|

Other DHCS programs |

283.7 |

367.2 |

83.6 |

29 |

|

Department of Public Health |

2,871.3 |

1,474.0 |

‑1397.3 |

‑49 |

|

Office of Statewide Health Planning and Developmenta |

141.7 |

803.9 |

662.2 |

467 |

|

Emergency Medical Services Authority |

83.7 |

59.9 |

‑23.8 |

‑28 |

|

Health and Human Services Agency |

6.6 |

105.0 |

98.4 |

1491 |

|

Totals |

$27,054.0 |

$33,709.0 |

$6655.2 |

25% |

|

aBeginning in 2021‑22, the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development is transitioning to become the Department of Health Care Access and Information. |

||||

|

DHCS = Department of Health Care Services. |

||||

As shown in an Appendix table, the year-over-year net growth in health program General Fund spending reflects a number of actions adopted by the Legislature as part of its 2021‑22 spending plan. Prominent among these actions are major new investments in behavioral health infrastructure as well as the provision of funding for the direct public health response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Health and Human Services Crosscutting Issues

Secretary of the California Health and Human Services (CHHS) Agency

Office of Systems Integration (OSI)

The spending plan includes $541.9 million for OSI—an office within the CHHS Agency—in 2021‑22, a 17.1 percent increase from revised 2020‑21 expenditures of $462.7 million. This year-over-year increase in expenditure authority is primarily attributable to OSI’s role in the planning, development, and implementation of the state’s Child Welfare Services-California Automated Response and Engagement System (CWS-CARES) information technology (IT) project and Electronic Visit Verification (EVV) Phase II IT project. We discuss these two projects below.

CWS-CARES IT Project

The state’s existing Child Welfare Services/Case Management System (CWS/CMS) is not compliant with current federal and state laws, regulations, and policies. The CWS-CARES IT project, once implemented, would replace CWS/CMS with a compliant IT system. The 2021‑22 Budget Act authorizes $64.8 million in increased expenditure authority for OSI to continue to serve its role in the development and implementation of CWS-CARES using a new approach. (One-time project funding across multiple state entities totals $128.5 million [$68.1 million General Fund] in 2021‑22.)

Continued Challenges With Development and Implementation of CWS-CARES IT Project. The administration’s attempts to replace CWS/CMS date back to 2005. Its most recent attempt—CWS-CARES—started in 2012. Initially planned using the traditional “waterfall” approach to project development and implementation, CWS-CARES then shifted to an “agile” iterative and incremental approach in 2015. Whereas projects that use the traditional waterfall approach to development and implementation generally do not implement a new system until it is completed, projects that use an agile approach iteratively develop a set of system functionalities and then implement them once they are completed (often before the entire system is done). However, the state’s initial attempt at agile development and implementation did not succeed mainly because the state had difficulty managing the large number of vendor contracts required for the project, hiring and retaining state staff to develop and implement the project, and acting as the system integrator due to a lack of experience.

New Approach to Development and Implementation Attempts to Address Past Challenges... In 2021, the federal Administration for Children, Youth, and Families (in the federal Health and Human Services Agency) and the California Department of Technology (CDT) approved a new plan for the CWS-CARES IT project that uses a modified agile approach to development and implementation. The administration says improved vendor contract management, reduced reliance on state staff for development and implementation, and an experienced vendor as system integrator will mitigate the risk of additional project delays. The CWS-CARES project team also plans to develop and implement a set of new system functionalities that does not need to integrate with the existing CWS/CMS. This will allow the team to evaluate the new approach and make any adjustments before proceeding with the development and implementation of the project.

…But Significantly Increases Project’s Cost and Extends Its Schedule. This new approach (combined with costs already incurred from past project activities) significantly increases the baseline project cost—from $420.8 million to $911.4 million, an increase of $490.6 million (or 117 percent)—and extends its schedule—from an implementation date of December 2023 to July 2025, a delay of 19 months. The baseline project cost and schedule likely will change again, however, due to annual updates to the current project plan required by CDT (including the cost, schedule, and scope of the project).

Provisional Language Withholds Some Funding Pending Administration’s Determination of Satisfactory Progress and Notification of Legislature. The spending plan includes $68.1 million General Fund to the Department of Social Services (DSS) for the development and implementation of the CWS-CARES IT project. Pursuant to budget act language, $28.6 million of the $68.1 million is withheld pending approval by the Department of Finance (in consultation with CDT) and notification of the Joint Legislative Budget Committee. The intent of the provisional language is for the CWS-CARES project team to demonstrate to the administration that “verified satisfactory progress” is made towards the completion of milestones within the project scope before additional expenditures are authorized.

EVV

Federal law requires states to implement EVV for Medicaid-funded personal care services by January 1, 2020 and for home health care services by January 1, 2023. EVV systems must collect and verify information about services performed—including the date and time of their delivery, the location, the types of services provided, and the individuals who provided and received care. The spending plan provides funding to plan and implement both phases of EVV and assumes some reduced federal Medicaid funds for failure to comply with set deadlines.

Personal Care Services (Phase I). The spending plan includes $1.2 million (nearly all General Fund) for DSS to continue implementation of EVV for personal care services—specifically for In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS)—in 2021‑22. (OSI continues to assist DSS with its implementation of EVV as part of the office’s maintenance and operation of the state’s Case Management Information and Payrolling System, the payroll and payment system for the IHSS program.) The federal government first granted the state a “good faith effort” time extension until January 1, 2021 for this implementation. However, the federal government later notified the administration that the state’s implementation of EVV for personal care services does not adequately capture the location of service and would need to be changed to avoid additional penalties. The administration expects to make these changes to its EVV system for personal care services by the end of 2021‑22. As a result, the spending plan assumes $53 million in reduced federal Medicaid funds (backfilled with General Fund) as penalties for noncompliance across five state entities—DSS, the Department of Developmental Services (DDS), the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), the Department of Aging, and the California Department of Public Health (CDPH).

Home Health Care Services (Phase II). The 2021‑22 Budget Act authorizes $21.2 million in increased expenditure authority for OSI to continue the planning, development, and implementation of EVV for home health care services across DHCS, DDS, and CDPH. (One-time project funding across state entities is $24.1 million [$5.8 million General Fund].) The administration expects the EVV system for home health care services to be implemented and in full compliance by January 1, 2023, at a total project cost of $46.3 million.

Behavioral Health-Related Augmentations

Provides Funding for Certain Components of the Children and Youth Behavioral Health Initiative. The spending plan provides funding to the CHHS Agency for certain components of the broader Children and Youth Behavioral Health Initiative (discussed later in this post). Specifically, the spending plan provides $25 million one-time General Fund in 2021‑22 to the Office of the Surgeon General (OSG) for a campaign focused on raising awareness of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and toxic stress. The spending plan also includes $10 million General Fund ongoing for the CHHS Agency to (1) convene subject matter experts to advise on implementation of the initiative and (2) commission an independent evaluation of all components of the initiative. Finally, the spending plan includes $100,000 General Fund to the CHHS Agency annually through 2025‑26 for state operations related to this initiative.

Office of Youth and Community Restoration (OYCR)

Funding to Establish OYCR. The spending plan provides a total of $27.6 million General Fund in 2021‑22 and $7.2 million General Fund in 2022‑23 and ongoing to establish OYCR (within the CHHS Agency)—which was created through Chapter 337 of 2020 (SB 823, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review). The funding is intended to provide 33 positions to perform the core functions of the office, including reviewing county juvenile plans, performing ombudsperson duties, reporting on youth outcomes, providing technical assistance to counties, administering grants, and identifying and disseminating best practices. One-time funding of $20 million is provided in 2021‑22 for OYCR to further support the transformation of local juvenile justice systems to support realigned responsibilities, improve youth outcomes, and address racial disparities in the juvenile justice system.

Other

Health Equity Initiatives at CHSS Agency and Across Its Departments. The spending plan provides a total of $27.6 million General Fund in 2021‑22, $4.1 million General Fund in 2022‑23, and $1.3 million General Fund in 2023‑24 and ongoing for several across-agency initiatives to address health inequities that were exacerbated by COVID-19.

- Language Access Resources. $20.3 million General Fund in 2021‑22 and $307,000 General Fund in 2022‑23 to (1) develop a language access framework and submit a report to the Legislature about this framework and (2) provide $20 million for multiple departments to improve and deliver language access services in their programs. Budget act language makes the $20 million contingent on completion of the framework and submission of the legislative report.

- Equity Dashboard. $3.2 million General Fund in 2021‑22 and $1.1 million General Fund in 2022‑23 and ongoing for the CHHS Agency and DHCS to develop an online dashboard across CHHS programs identifying data gaps and disparities by race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender identity.

- CHHS Workforce Training on Equity Issues. $2.5 million General Fund in 2021‑22 and in 2022‑23 for voluntary training of health and human services state employees on equity issues.

- Post-COVID-19 Analysis. $1.7 million General Fund in 2021‑22 and $154,000 General Fun d in 2022‑23 and ongoing to conduct a retrospective analysis of the intersection of COVID-19 and health disparities and health equity. Budget act language requires the analysis to include recommendations for how CHHS departments should address these inequities. A preliminary analysis is due to the Legislature on May 1, 2022 and final recommendations are due January 10, 2023.

California Health and Human Services Data Exchange Framework. The spending plan includes $2.5 million one time from the General Fund to develop a framework, including a single data sharing agreement and common set of policies and procedures, to govern the exchange of health information among health care entities and government agencies. Budget-related legislation requires the framework to be established by July 1, 2022 and the data sharing agreement to be executed among participating entities—including health plans, clinical laboratories, health providers, and health facilities—by January 31, 2023. Active participation in the exchange must begin by January 31, 2024 for all health plans, clinical laboratories, large providers, and large health facilities, and by January 31, 2026 for smaller providers and smaller facilities by January 31, 2026.

Center for Data Insights and Innovation. The spending plan provides $443,000 ongoing from the Data Insights Innovation Fund to establish the center within the CHHS Agency. This reflects the consolidation and redirection of resources and positions from several existing offices. The center will serve as a centralized data and information hub across health and human services programs and will include analytic tools, research, and dashboards.

Implementation of the California Affordable Drug Manufacturing Act. The spending plan provides $2 million one time from the General Fund to implement Chapter 207 of 2020 (SB 852, Pan), that requires the CHHS Agency to take specified actions related to increasing patient access to affordable drugs. Resources will be used for research and analytical tasks associated with implementation.

Home- and Community-Based Services Spending Plan

The American Rescue Plan (ARP) Act allows states draw down enhanced federal funding for home- and community-based services (HCBS) funded through the Medicaid program, provided that states spend the additional federal funding on HCBS program enhancements. Under this provision of the ARP, California is eligible to draw down an estimated additional $3 billion in federal Medicaid funds. Budget-related legislation authorizes the state to draw down this additional federal funding and places parameters on how the state may spend the additional funding on HCBS program enhancements.

As required by the ARP Act, the administration submitted an HCBS spending plan proposal to the federal government indicating how much additional federal Medicaid funding the state would draw down and detailing the HCBS enhancements that the state would make using the additional federal funding. (As of September 3, the federal government had approved 13 of 28 projects in the state’s proposed plan, partially approved 14 [with a request for more information], and rejected one. For the latter, DHCS intends to use that funding to augment one of the approved projects. DHCS submitted a revised spending plan to the federal government on September 17, 2021.) The HCBS enhancements will occur in programs operated across the CHHS Agency and include, for example, reimbursement rate increases for DDS providers, a Medi-Cal managed care incentive payment program aimed at addressing homelessness, and a community care expansion program to improve access to assisted living in the state. Because many of the proposed HCBS enhancements are eligible for federal Medicaid funding, the state will draw down an additional $1.6 billion in federal Medicaid funds on top of the $3 billion the state more directly receives through the federal funding enhancement under the ARP Act. Accordingly, under the spending plan, the state will spend $4.6 billion on HCBS enhancements over the next several years. We describe this component of the spending plan in detail in a forthcoming post on the HCBS spending plan.

Medi-Cal

This section describes the Medi-Cal spending plan. First, we provide an overview of the major drivers of the growth in Medi-Cal spending between 2020‑21 and 2021‑22 and, second, we describe the major augmentations that were approved as part of the 2021‑22 Budget Act. (We discuss Medi-Cal behavioral health augmentations other than those included under the California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal [CalAIM] initiative later in the behavioral health section of this post.)

Overview of Medi-Cal Spending Plan. As shown in Figure 2, the spending plan provides $28 billion General Fund ($123.7 billion total funds) for Medi-Cal in 2021‑22. This reflects a 30 percent year-over-year increase in General Fund spending in Medi-Cal compared to 2020‑21, and a smaller 7 percent increase in total spending in Medi-Cal across these two years.

Figure 2

Medi‑Cal Spending Plan

(Dollars in Billions)

|

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

Change From |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

|||

|

Federal funds |

$79.0 |

$83.3 |

$4.3 |

5% |

|

General Fund |

21.5 |

28.0 |

6.5 |

30 |

|

Other nonfederal funds |

15.1 |

12.4 |

‑2.7 |

‑18 |

|

Total Funds |

$115.6 |

$123.7 |

$8.1 |

7% |

|

Note: Reflects Medi‑Cal local assistance spending. |

||||

As the following bullets describe, this year-over-year growth in projected spending is driven by a large number of discretionary augmentations and technical adjustments to the Medi-Cal budget.

- Discretionary Augmentations. Over 30 discretionary augmentations in Medi-Cal were approved in the 2021‑22 Budget Act. These collectively account for $2.1 billion (32 percent) of the $6.5 billion year-over-year increase in General Fund Medi-Cal spending going into 2021‑22. The major discretionary augmentations include various behavioral health investments ($795 million General Fund); support for CalAIM implementation ($651 million General Fund); rate increases and other, generally one time, financial support for providers ($396 million General Fund); several eligibility expansions ($117 million General Fund); and a number of benefit, modality, and workforce expansions ($78 million General Fund).

- Technical Adjustments. A large number of technical adjustments account for the remaining $4.4 billion (68 percent) of the year-over-year net increase in General Fund spending in Medi-Cal. The largest technical adjustments include (1) $2.4 billion in higher net General Fund costs related to COVID-19, $1.4 billion General Fund of which is attributable to the pandemic-related projected increase in caseload; (2) higher per-enrollee costs of around $500 million General Fund; (3) and roughly $500 million General Fund to ensure that state-only Medi-Cal populations are funded at appropriate federal-state cost-sharing levels (per federal rules, the federal government will only pay its standard share of cost for emergency- and pregnancy-related services for state-only populations).

CalAIM

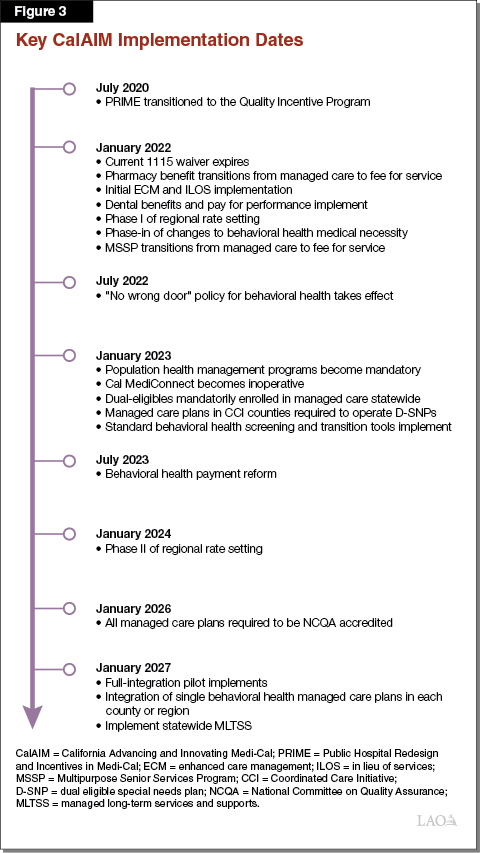

Overview of CalAIM. CalAIM is a large package of reforms aimed at (1) reducing health disparities by focusing attention and resources on Medi-Cal’s high-risk, high-need populations; (2) rethinking behavioral health service delivery and financing; (3) transforming and streamlining managed care; and (4) extending federal funding opportunities currently available under the state’s soon-to-expire 1115 waiver (a federal Medicaid waiver). As shown in Figure 3, CalAIM’s various reforms will be implemented on a staggered basis over the next several years beginning in January 2022. While some CalAIM reforms may be implemented under administrative authority, budget-related legislation authorizes most of the major reforms under CalAIM. Implementation of CalAIM generally requires federal approval, which is anticipated to occur for most CalAIM reforms in fall 2021. The following bullets describe several of the major CalAIM reforms.

- Addressing the Needs of Medi-Cal’s High-Risk, High-Needs Populations. CalAIM includes three major reforms aimed at addressing the health and social needs of Medi-Cal’s high-cost, high-need populations. First, under CalAIM, all Medi-Cal managed care plans would be required to operate population health management programs. Population health management programs represent a bundle of administrative activities that aim to (1) identify beneficiaries’ medical and nonmedical risks and needs and (2) facilitate care coordination and referrals. Second, CalAIM creates a new statewide enhanced care management benefit through which managed care plans would provide (or contract out for) intensive case management and care coordination for their highest-risk, highest-need members. Third, CalAIM authorizes and establishes a payment mechanism for managed care plans to provide 14 nonmedical services—known as “in lieu of services”—to their members. These new services will be optional for managed care plans to provide and beneficiaries to accept. The new in lieu of services include, for example, housing deposits and navigation services, medically tailored meals, home accessibility modifications, and medical respite.

- Rethinking Behavioral Health Service Delivery and Financing. CalAIM makes a variety of reforms to Medi-Cal behavioral health service delivery and financing. (Behavioral health services include both mental health and substance use disorder services.) These reforms generally are intended to (1) increase access to Medi-Cal behavioral health services—for example, by leveraging additional federal funding for behavioral health services (including for residential mental health services) and revising medical necessity criteria to make it easier for beneficiaries to initiate treatment, and (2) streamline the Medi-Cal behavioral health reimbursement model.

- Transforming and Streamlining Managed Care. CalAIM makes various changes to create more standardization across the state within Medi-Cal managed care while also improving plan capacities to coordinate their members’ care. For example, CalAIM transitions responsibility for payment for institutional long-term care and organ transplants from Medi-Cal’s fee-for-service delivery system into managed care on a statewide basis. In addition, CalAIM establishes a new approach for coordinating the care of Medi-Cal beneficiaries also on Medicare. As a final example, Medi-Cal managed care plans would be required to obtain accreditation from the National Committee on Quality Assurance.

- Extends Federal Authorities and Funding Opportunities Currently Under the State’s 1115 Waiver. Major pieces of the Medi-Cal program are authorized and funded through the state’s 1115 federal waiver. This waiver generally is available for states to demonstrate delivery system and financing reforms that to do not adhere to standard federal Medicaid rules. Such pieces include the Medi-Cal managed care program, two major public hospital finance programs, the Drug Medi-Cal Organized Delivery System, and initiatives aimed at improving access to dental care. California’s current 1115 waiver is set to expire on December 31, 2021. Under CalAIM, the state would transition authorization of certain pieces of the Medi-Cal program—such as Medi-Cal managed care—to alternative, generally more sustainable, federal authorities. The state also is applying to renew certain programs under the 1115 waiver, including, for example, one of the state’s public hospital finance programs known as the Global Payment Program.

Multiyear CalAIM Spending Plan. CalAIM is expected result in both one-time and ongoing costs, which generally will be shared between the federal and state governments. To support the first half-year of CalAIM implementation from January 2022 through June 2022, the spending plan dedicates $664 million General Fund ($1.1 billion total funds) in 2021‑22. Over the first four years of implementation, nearly $2.8 billion General Fund ($5.7 billion total funds) is projected to have been spent on CalAIM. Figure 4 summarizes the multiyear CalAIM spending plan. The following bullets summarize the major funding components of the CalAIM spending plan:

- Incentive Funding for Managed Care Plan Capacity Building. To help plans build the capacity to provide enhanced care management and in lieu of services, the spending plan provides $150 million General Fund ($300 million total funds) in incentive funding in 2021‑22. In 2022‑23 and 2023‑24, the multiyear CalAIM spending plan would provide $300 million General Fund ($600 million total funds) annually, after which this funding would expire. Allocation of these funds will be based on plans meeting various performance targets, including, for example, the development of health and care management documentation systems, building enhanced care management provider capacity, and making in lieu of services available to members.

- Enhanced Care Management. As previously noted, CalAIM requires all Medi-Cal managed care plans to provide enhanced care management to their highest-risk, highest-need members. Implementation will phase in over several years, beginning in January 2022. To cover the half-year costs of this new benefit, the spending plan provides $94 million General Fund ($188 million total funds) in 2021‑22. On an ongoing basis, enhanced care management costs are expected to grow to $233 million General Fund ($467 million total funds).

- In Lieu of Services. Although optional for managed care plans to make available—and beneficiaries to utilize—under federal rules, plans’ expected costs of providing in lieu of services must be reimbursed by the state. To cover these costs beginning in January 2022, the spending plan provides $24 million General Fund ($48 million total funds). Ongoing costs are projected to be $58 million General Fund ($115 million total funds).

- Expanding Access to Dental Services. From 2016 through 2021, the state has implemented a demonstration project aimed at improving access to dental care for children on Medi-Cal. Under the demonstration project, dental providers could receive incentive payments for meeting various performance targets, such as ensuring continuity of care for their Medi-Cal patients and increasing utilization of preventive services and assessments. Under CalAIM, most of the initiatives under the demonstration project will be made permanent. The spending plan provides half-year funding of $57 million General Fund ($116 million total funds) to expand dental services through CalAIM. On an ongoing basis, $114 million General Fund ($232 million total funds) is projected to be provided for this purpose.

- Delivery System Transitions. Under CalAIM, certain Medi-Cal benefits and enrollee populations would be moved from the fee-for-service delivery system to the managed care delivery system (and vice versa). Delivery system transitions generally result in one-time costs due to differences in the timing with which payments are made between fee for service and managed care. In addition, some delivery system transitions can result in ongoing costs or savings. The spending plan provides $175 million General Fund ($403 million total funds) in 2021‑22 for delivery system transitions. On an ongoing basis, the spending plan projects $5 million in General Fund savings from transferring responsibility for funding and providing most Medi-Cal mental health services from Kaiser Foundation Health Plan to the counties in Sacramento and Solano counties. (Kaiser Foundation Health Plan currently arranges and pays for these services for their Medi-Cal members.)

- Other CalAIM Spending Items. The budget funds a number of other CalAIM initiatives. For 2021‑22, these include (1) $100 million General Fund ($200 million total funds) for the Medi-Cal Providing Access and Transforming Health (PATH) initiative, aimed at improving pre-release care and coordination for incarcerated individuals; (2) $30 million General Fund ($300 million total funds) to procure a statewide Medi-Cal population health management service, a centralized data repository and portal whereby authorized users could obtain administrative and clinical data on Medi-Cal recipients for care coordination and performance monitoring purposes; (3) and $22 million General Fund for the Behavioral Health Quality Improvement Program (QIP) to improve counties’ capacity to successfully adopt the various behavioral health reforms in CalAIM. Funding for the Medi-Cal PATH initiative and the population health management service largely is expected to be one time in 2021‑22, while funding for Behavioral Health QIP is intended to reach $86 million General Fund spread out over three years.

Figure 4

Multiyear CalAIM Spending as of the 2021‑22 Budget Act

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

||||||||

|

Total Funds |

General Fund |

Total Funds |

General Fund |

Total Funds |

General Fund |

Total Funds |

General Fund |

||||

|

Local Assistance |

|||||||||||

|

Plan incentivesa |

$300 |

$150 |

$600 |

$300 |

$600 |

$300 |

— |

— |

|||

|

Enhanced care management |

188 |

94 |

467 |

233 |

467 |

233 |

$467 |

$233 |

|||

|

In lieu of services |

48 |

24 |

115 |

58 |

115 |

58 |

115 |

58 |

|||

|

Expanding access to dental services |

116 |

57 |

232 |

114 |

232 |

114 |

232 |

114 |

|||

|

Benefit and population delivery system transitionsb |

403 |

175 |

‑5 |

‑5 |

‑5 |

‑5 |

‑5 |

‑5 |

|||

|

Otherc |

522 |

152 |

82 |

81 |

127 |

113 |

95 |

81 |

|||

|

Local Assistance Totals |

$1,577 |

$651 |

$1,491 |

$781 |

$1,536 |

$812 |

$904 |

$480 |

|||

|

State Operations |

$40 |

$13 |

$44 |

$15 |

$40 |

$14 |

$24 |

$12 |

|||

|

Grand Totals |

$1,616 |

$664 |

$1,535 |

$796 |

$1,576 |

$826 |

$928 |

$492 |

|||

|

aTo assist with the establishment of enhanced care management and in lieu of services. b Reflects the costs of moving certain benefits, such as institutional long‑term care, and populations, such pregnant women, from fee for service to managed care and vice versa for other benefits and populations. c Includes costs, for example, for the statewide Population Health Management service, the Medi‑Cal Providing Access and Transforming Health, and the Behavioral Health Quality Improvement Program. |

|||||||||||

Eligibility Expansions

The spending plan includes a number of eligibility expansions, the major ones of which we describe in this section. To support Medi-Cal eligibility expansions, the spending plan provides $117 million General Fund ($190 million total funds) in 2021‑22. Annual costs for these eligibility expansions are projected to grow to around $1.7 billion General Fund by 2024‑25.

Expands Comprehensive Medi-Cal Coverage to Income-Eligible Undocumented Immigrants Ages 50 and Older. Historically, income-eligible undocumented immigrants only qualified for “restricted-scope” Medi-Cal coverage, which covers their emergency- and pregnancy-related service costs. Beginning in 2016, the state expanded comprehensive, or “full-scope,” Medi-Cal coverage to undocumented immigrants ages 18 and younger. In 2020, the state further expanded full-scope Medi-Cal coverage to income-eligible undocumented immigrants ages 19 through 25. The spending plan extends full-scope coverage to income-eligible undocumented immigrants ages 50 and older. Under budget-related legislation, implementation of this coverage expansion would occur no sooner than May 2022. Nearly 240,000 undocumented immigrants are expected to gain full-scope coverage under this expansion. The spending plan provides $48 million General Fund ($67 million total funds) in 2021‑22 (covering the final two months of the fiscal year) to fund the expansion. Costs are assumed to grow over time as newly eligible individuals gradually join the program in higher numbers and increase their utilization of services. By 2024‑25, annual costs are expected to reach $1.3 billion General Fund ($1.5 billion total funds). A little more than half of the costs are expected to fall within the IHSS program operated by DSS (for which this expansion population would become newly eligible), with the remaining costs falling within Medi-Cal.

Temporarily Relaxes and Then Eliminates Medi-Cal Asset Limits for Seniors and Persons With Disabilities. Currently, seniors and persons with disabilities’ Medi-Cal eligibility depends on their having nonexempt assets of lesser or equal value to the asset limit. (Medi-Cal’s other caseload groups are not subject to the asset limit.) Beginning no sooner than July 2022, the spending plan raises the Medi-Cal asset limit from $2,000 to $130,000 for individuals and from $3,000 to $195,000 for couples. Subsequently, but no sooner than January 2024 and only after necessary federal approvals are obtained, the asset limit would be eliminated altogether. The relaxation and subsequent elimination of the asset test are expected to increase the number of seniors and persons with disabilities enrolled in Medi-Cal by around 37,000 enrollees. Annual costs for this expansion are projected to start at $197 million General Fund ($394 million total funds) and then grow with medical inflation, caseload, and utilization changes. The multiyear spending plan assumes these costs begin in 2022‑23.

Extends Postpartum Coverage to a Year After Childbirth. Medi-Cal eligibility generally is limited to adults with incomes at or below 138 percent of the federal poverty level. However, as authorized by federal law, pregnancy and postpartum Medi-Cal coverage is available to individuals with incomes up to 213 percent of the federal poverty level. Historically, this coverage extended through the first two months of the postpartum period. In 2019‑20, the Legislature extended the postpartum period of coverage to 12 months after childbirth for mothers with a mental health condition using state dollars. For the period of April 2022 through March 2027, the ARP Act gives states the option to extend pregnancy and postpartum Medicaid coverage from 2 months to 12 months after childbirth, with the federal government sharing in the cost at standard cost-sharing ratios. The spending plan authorizes this extension of postpartum coverage in Medi-Cal, which would remain in place for as long as federal Medicaid funding is available. After federal authority and funding expires, state law would revert to pre-existing rules whereby postpartum coverage would only last for a full 12-month period if the mother has a mental health condition. At any time while the expansion remains in effect, 46,000 postpartum women are expected to gain extended coverage under this change. To fund this temporary expansion, the spending plan provides $45 million General Fund ($90 million total funds) in 2021‑22 (to fund three months of the expansion) and around $180 million General Fund ($360 million total funds) thereafter annually until the federal authority expires.

Provides Accelerated Enrollment for Adults. Currently, Medi-Cal eligibility is not granted to adults applying online until after their incomes have been verified against administrative income records. The spending plan provides $8 million General Fund ($17 million total funds) to instead extend accelerated enrollment to such adults ages 19 through 64. Under this change—which is intended to aid in a settlement to a lawsuit against DHCS alleging that application processing is too slow—applicants would immediately qualify for Medi-Cal benefits while their income verifications are pending.

Benefit, Modality, and Workforce Expansions

This section describes the major benefit, modality, and workforce expansions approved in the 2021‑22 spending plan. To support these changes, the spending plan provides $78 million General Fund ($203 million total funds) in 2021‑22.

Temporarily Extends Telehealth Policies in Place During COVID-19 and Provides Coverage for Remote Patient Monitoring. In early 2020, the federal government declared a national public health emergency in response to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and waived certain Medicaid health care delivery requirements for the duration of the emergency. In California, DHCS used this authority to adopt several temporary flexibilities in the Medi-Cal program related to the delivery of telehealth services. (For example, for the duration of the national public health emergency, Medi-Cal is reimbursing telehealth services provided through telephone at parity with services provided in person.) The spending plan temporarily extends these telehealth flexibilities through December 2022. The costs of extending these telehealth flexibilities are projected to be $19.2 million General Fund ($54.3 million total funds) in 2021‑22 and $9.6 million General Fund ($19.2 million total funds) for a half year in 2022‑23. Alongside this temporary expansion of Medi-Cal telehealth flexibilities, the spending plan includes budget-related legislation requiring DHCS to convene a stakeholder workgroup to provide recommendations on what permanent Medi-Cal telehealth policy should be. The spending plan includes $1 million General Fund ($2 million total funds) in 2021‑22 for this workgroup. Finally, the spending plan includes $33.1 million General Fund ($94.8 million total funds) in 2021‑22 to add remote patient monitoring—a telehealth service through which clinicians receive physiological data on their patients that is collected by remote monitoring devices—as a covered benefit in the Medi-Cal program. The ongoing costs of this new benefit are projected to be $37.2 million General Fund ($106.4 million total funds) annually beginning in 2022‑23.

Adds New Benefits. As the following bullets describe, in addition to the remote patient monitoring benefit described previously, the spending plan adds several new Medi-Cal benefits.

- Continuous Glucose Monitoring. Continuous glucose monitors are wearable devices that measure glucose levels at regular intervals to help individuals manage their diabetes. Currently, continuous glucose monitors are a covered benefit for Medi-Cal beneficiaries ages 21 and under. Beginning January 2022, the spending plan expands coverage of continuous glucose monitors to Medi-Cal beneficiaries with Type I diabetes over age 21. The 2021‑22 half-year costs of the expansion are projected at $1.5 million General Fund ($5.6 million total funds). On an ongoing basis, the benefit is projected to result in net General Fund savings in the low millions of dollars due to newly negotiated rebates on the monitors and the reduction in costs for standard blood glucose monitors (finger pricks).

- Doula Benefit. Doula services are emotional and physical supportive services provided to women through pregnancy, labor, birth, and the postpartum period. The spending plan adds doula services as a covered benefit beginning January 2022. The spending plan provides $200,000 General Fund ($550,000 total funds) for the first half year of implementation in 2021‑22, and $2 million General Fund ($4 million total funds) on an ongoing annual basis.

- Infant Whole Genome Sequencing. The 2018‑19 spending plan established the Medi-Cal Whole Genome Sequencing Pilot Project, the goal of which was to investigate the potential value of using rapid whole genome sequencing in the diagnosis and treatment of infants in intensive care. Following the successful conclusion of the pilot project, the 2021‑22 spending plan adds rapid whole genome sequencing as a benefit for children ages one year old and younger in intensive care beginning in January 2022. The costs of the expansion are estimated to be $3 million General Fund ($6 million total funds) in 2021‑22 and in the low millions of dollars General Fund annually on an ongoing basis.

- Medication Therapy Management. In 2019, the Medi-Cal fee-for-service pharmacy reimbursement methodology was changed, resulting in lower reimbursement. Certain pharmacy providers objected to the change, asserting that the lower reimbursement could cause them to cease providing specialized medication management services to high-risk populations, which may include individuals who are homeless, have mental illness, or have a history of non-adherence with medications. To ensure continued access to medication management services without making broader changes to the new pharmacy reimbursement methodology, the spending plan establishes the Medication Therapy Management program, through which pharmacies that contract with DHCS will be able to bill the department for encounters with qualifying beneficiaries. First-year costs are expected to be $5 million General Fund ($14 million total funds), while annual ongoing costs are expected to be $14 million General fund ($41 million total funds).

Authorizes Community Health Workers to Provide Appropriate Medi-Cal Benefits. Community health workers are trained health educators who work directly with individuals who may have difficulty understanding or interacting with health care providers due to cultural or language barriers. Community health workers are intended to help increase engagement between underserved communities and the health care system. The spending plan includes $6.2 million General Fund ($16.3 million total funds) to add community health workers as a new provider type in the Medi-Cal program, effective January 1, 2022. (Under the spending plan, community health workers would provide certain clinically appropriate Medi-Cal benefits and services under the supervision of a traditional, licensed Medi-Cal provider.) The costs of adding community health workers to the Medi-Cal program are expected to ramp up over time, eventually reaching $76 million General Fund ($201 million total funds) ongoing beginning in 2026‑27.

Reimbursement Changes and Financial Support for Providers

As this section describes, the spending plan increases Medi-Cal reimbursement rates for certain provider types and provides largely one-time funding to select providers. In 2021‑22, $396 million General Fund ($428 million total funds) is projected to be spent on these reimbursement changes and one-time financial support.

Eliminates Reimbursement Rate Freeze for Certain Long-Term Care Facilities. Intermediate Care Facilities for the Developmentally Disabled and Freestanding Pediatric Subacute facilities are long-term care facilities that provide 24-hour personal care, developmental, skilled nursing, and other services to persons with developmental disabilities or other significant health care needs. In response to the fiscal challenges of the Great Recession, the state imposed a Medi-Cal rate freeze for some of these long-term care facilities and up to a 10 percent reduction to the Medi-Cal rates paid to other facilities of this kind. (Many other health care provider types beside long-term care facilities were subject to similar rate reductions.) Beginning in August 2021, the spending plan removes the rate freeze and rate reductions that apply to these long-term care facilities. Additionally, budget-related language approved alongside the spending plan ensures that the ongoing rates paid to these long-term care facilities include the supplemental payments that have been provided since 2017 with funding from the Proposition 56 (2016) tobacco tax increase.

Forgives Recoupments and Raises Rate Cap for Clinical Laboratories. In 2020, the state made various changes to the reimbursement methodology for clinical laboratories, including capping reimbursement at 80 percent of what Medicare would pay for clinical laboratory services. Clinical laboratories were subject to retroactive recoupments to ensure conformity with the 2020 reimbursement changes for the period after the changes went into effect but before they could be implemented. These retroactive recoupments were set to continue through 2021‑22. For 2021‑22, the spending plan undoes the 2020 reimbursement changes for clinical laboratories, thereby reverting to the methodology in place in 2019, and forgives the recoupments associated with the 2020 changes. Beginning in 2022‑23, the spending plan raises the reimbursement cap from 80 percent to 100 percent of what Medicare would pay for clinical laboratory services. The costs of these changes in 2021‑22 are projected to be $25 million General Fund ($32 million total funds).

Ends Rate Reduction for Complex Rehabilitation Technology. Complex rehabilitation technology is a type of durable medical equipment that is individually configured to meet individuals’ mobility and other daily living needs. Customized wheelchairs are one example of complex rehabilitation technologies. As with many health care providers, Medi-Cal reimbursement rates for complex rehabilitation technology and other durable medical equipment were reduced by up to 10 percent in the aftermath of the Great Recession. The spending plan removes this 10 percent rate reduction for complex rehabilitation technology. Additionally, budget-related language adds definitions of complex rehabilitation technology and associated services and establishes standards related to the delivery of these services. Such standards include that suppliers be accredited by a relevant body and meet the quality standards of the federal Medicare program. The cost of this reimbursement change is expected to be $2 million General Fund ($4 million total funds).

Provides One-Time Funding for Certain Health Care Providers. The spending plan provides one-time financial support to a variety of health care providers, including (1) $300 million General Fund in financial relief for designated public hospitals, which have reported financial strain due to COVID-19; (2) $30 million General Fund to support the Kedren Community Health and Acute Psychiatric Hospital; (3) $15 million General fund to support construction costs for the Alameda Wellness Respite Center; and (4) $2 million General Fund for free clinics.

Behavioral Health

Children and Youth Behavioral Health Initiative

The spending plan includes a package of augmentations—across several state health departments—known collectively as the Children and Youth Behavioral Health Initiative. This initiative generally is intended to transform the state’s behavioral health delivery system for children and youth (defined as age 25 and under) regardless of payer source by adopting a more prevention-oriented statewide approach to behavioral health care for children and youth. The spending plan includes $1 billion General Fund ($1.5 billion total funds) in 2021‑22 for the initiative, and the total costs of the initiative are projected to be $3.4 billion General Fund ($4.4 billion total funds) across five years through 2025‑26. As mentioned earlier, the Children and Youth Behavioral Health Initiative consists of a package of distinct augmentations. The major components of the initiative are described below. (One major component of the initiative—funding provided to acquire or rehabilitate facilities for behavioral health treatment for children and youth—is part of the Behavioral Health Continuum Infrastructure Program discussed in a later section.)

Provides Funding for Behavioral Health Virtual Platform for Children and Youth. The spending plan provides $10 million General Fund in 2021‑22 to DHCS to establish—through procurement of a vendor—a virtual platform that would facilitate the provision of behavioral health services to children and youth age 25 and younger regardless of payer source through (1) interactive exercises and games, (2) automated screening and assessment tools, and (3) direct services delivered by peers or coaches. In addition, the virtual platform would facilitate referrals to appropriate health care delivery systems for children and youth (whom the assessment and screening tools indicate have higher behavioral health needs) to set up appointments with a clinician for behavioral health care and provide capacity for remote consultations between health care providers (known as eConsult). The total cost of this behavioral health virtual platform is projected to be $637.7 million General Fund ($749.7 million total funds) across the five years of the initiative.

Provides Funding for School Behavioral Health Capacity. The Children and Youth Behavioral Health Initiative includes three distinct augmentations intended to increase capacity for providing behavioral health services in schools. These augmentations are described in the bullets below.

- School-Linked Partnership Capacity and Infrastructure Grants. The spending plan includes $100 million General Fund in 2021‑22 and $450 million General Fund in 2022‑23 to DHCS to provide grant funding to a variety of eligible entities (including schools, community colleges, universities, health insurance plans, community-based organizations, behavioral health providers, tribal entities, and counties) to build infrastructure and capacity for establishing partnerships to provide behavioral health services in schools (for example, data sharing systems so that entities can better coordinate school behavioral health services). Of these amounts, $30 million in 2021‑22 and $120 million in 2022‑23 is targeted at higher education students, and $70 million in 2021‑22 and $330 million in 2022‑23 is targeted at K-12 students. (A further description of the higher education component can be found in our Higher Education spending plan post [The 2021‑22 California Spending Plan: Higher Education].)

- Incentive Payments to Medi-Cal Managed Care Plans. The spending plan includes $194.5 million General Fund ($389 million total funds) one-time in 2021‑22 to DHCS to provide incentive payments to Medi-Cal managed care plans to build infrastructure for establishing partnerships with schools and county behavioral health. These incentive payments are intended to increase the number of K-12 students receiving behavioral health services—with a particular focus on prevention and early intervention services—through Medi-Cal. Under the spending plan, incentive payments would be provided to managed care plans for a variety of activities. These activities include, for example, (1) local planning efforts to identify service gaps, (2) establishing contracts with schools to provide behavioral health services on-site, and (3) providing technical assistance to schools to ensure services are reimbursed through Medi-Cal.

- Additional Funding for Mental Health Student Services Act Grant Program. The spending plan includes $205 million ($105 million Mental Health Services Fund and $100 million Coronavirus Fiscal Recovery Fund) one time in 2021‑22 to the Mental Health Services Oversight and Accountability Commission (MHSOAC) to provide additional funding to the Mental Health Student Services Act Grant Program, which provides grants to encourage county-school partnerships and increase student access to mental health services. Eligible activities under this grant program include, for example, (1) provision of school-based mental health services, (2) suicide prevention services, (3) dropout prevention services, and (4) outreach to vulnerable youth.

Provides Funding for Children and Youth Behavioral Health Workforce. The spending plan includes (1) $308 million General Fund in 2021‑22 and $118.8 million General Fund in 2022‑23 to the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) to increase behavioral health workforce capacity targeted at children and youth and (2) $267 million General Fund—$338.3 million General Fund across the five years of the initiative—to OSHPD to develop a statewide behavioral health counselor and coach workforce. (We provide a further description of these spending plan augmentations in the OSHPD section of this post.) Furthermore, the spending plan provides $50 million General Fund in 2022‑23 to DHCS for behavioral health training for pediatric, primary care, and other health care providers.

Provides Grants to Support Evidence-Based Behavioral Health Practices for Children and Youth. The spending plan includes $429 million General Fund in 2022‑23 to DHCS to provide grant funding to a variety of eligible entities (including commercial health insurance plans, Medi-Cal managed care plans, community-based organizations, behavioral health providers, tribal entities, cities, and counties) to support the provision of designated evidence-based behavioral health interventions to children and youth. Grant funding provided to counties will be administered through the CalAIM behavioral health QIP (discussed earlier). These designated evidence-based practices will be selected by a workgroup—convened by DHCS as required by budget-related legislation—of behavioral health subject matter experts and stakeholders.

Provides New Dyadic Services Benefit. The spending plan includes $100 million General Fund ($200 million total funds) ongoing beginning in 2022‑23 to DHCS to provide a new benefit in the Medi-Cal program for dyadic care—a model of care which provides integrated physical and behavioral health screening and services to children and youth and their families. For example, under this new benefit both children and youth and their families could receive screening for social determinants of health such as food insecurity and housing instability.

Provides Funding for Behavioral Health Public Education Campaign. The spending plan provides $5 million General Fund in 2021‑22 and $50 million General Fund in 2022‑23 to CDPH for a public education campaign to raise awareness for behavioral health issues, specifically with the goals of (1) raising the behavioral health literacy of all Californians and (2) normalizing the prevention and early intervention of behavioral health issues. (We further discuss this public education campaign in the CDPH section of this post.) Total costs of this public education campaign are projected to be $100 million General Fund across the five years of the initiative.

Provides Funding to Continue CalHOPE Program. The spending plan includes $45 million General Fund one time in 2021‑22 to DHCS to continue the CalHOPE Student Support Program, which provides free crisis counseling and support services through a centralized resource website. (CalHOPE was established using federal funds in 2020, in response to the behavioral health challenges resulting from the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.) The funding is intended to sustain the program until the Behavioral Health Virtual Platform (discussed earlier) is implemented.

Provides Funding to CHHS Agency for Certain Components of Initiative. As discussed earlier in the CHHS Agency section of this post, the spending plan provides $25 million one-time General Fund in 2021‑22 to the OSG for a campaign focused on raising awareness of ACEs and toxic stress. The spending plan also includes $10 million General Fund ongoing for the CHHS Agency to (1) convene subject matter experts to advise on implementation of the initiative and (2) commission an independent evaluation of all components of the initiative.

Other Children and Youth Behavioral Health Initiative Changes. The spending plan includes budget-related legislation (1) requiring DHCS to develop a statewide fee schedule for behavioral health services provided in schools and (2) requiring health insurance plans to cover medically necessary behavioral health services provided at school sites effective January 1, 2024. Furthermore, the spending plan provides $27.5 million General Fund ($65 million total funds) to DHCS for state operations associated with the initiative. Total DHCS state operations costs of the initiative are projected to be $63.5 million General Fund ($127 million total funds) across the five years of the initiative.

Behavioral Health Continuum Infrastructure Program

Provides Grants to Local Entities to Acquire or Rehabilitate Facilities for Behavioral Health Treatment. The spending plan includes $445.7 million General Fund ($755.7 million total funds) in 2021‑22, $1.2 billion General Fund ($1.4 billion total funds) in 2022‑23, and $2.1 million in 2023‑24 to DHCS to provide competitive grants to local entities to increase behavioral health infrastructure, predominantly by constructing, acquiring, or renovating facilities for community behavioral health services (contingent on these entities providing matching funds and committing to providing funding for ongoing services). Grants provided under this program are intended to fund a variety of community behavioral health facility types to treat individuals with varying levels of behavioral health needs. For example, funds could be used on (1) short-term crisis treatment beds, (2) residential treatment facilities in which treatment typically lasts for a few months, or (3) longer-term rehabilitative facilities. Certain portions of the total amounts discussed above for this program are earmarked for more specific purposes or targeted at more specific populations. Specifically, $150 million General Fund in 2021‑22 is reserved for the establishment of mobile behavioral health crisis teams, and $25 million General Fund ($245 million total funds) in 2022‑23 is reserved for community behavioral health facilities targeted at children and youth.

Other Behavioral Health Augmentations

The spending plan includes funding for two other behavioral health augmentations. First, the spending plan includes $40 million (HCBS-related funds) to DHCS for the existing CalBridge Behavioral Health Pilot Project, which provides grants to hospitals to hire behavioral health counselors in emergency departments. (This augmentation is a component of the broader HCBS spending plan discussed earlier as well as in a separate post.) The spending plan also includes $5 million Mental Health Services Fund to the MHSOAC to support a peer social media project for children and youth to mitigate the effects of bullying.

Department of State Hospitals (DSH)

Under the spending plan, General Fund spending for DSH will be $2.6 billion in 2021‑22, an increase of $738 million, or about 40 percent, from the revised 2020‑21 level. This net increase generally reflects the approval of several new discretionary augmentations, which we describe below.

Incompetent to Stand Trial (IST) Issues

Provides Funding for Additional IST Treatment Capacity. The spending plan includes $376.9 million from the General Fund in 2021‑22 for additional IST treatment capacity. This includes (1) $267.1 million General Fund in 2021‑22—ramping down to $145.5 million General Fund in 2024‑25 and ongoing—for DSH to contract for (and subsequently oversee) additional bed capacity in the community to address the increasing number of felony IST referrals to the department, (2) $47.6 million General Fund in 2021‑22 and $1.2 million General Fund in 2022‑23 and ongoing to expand the felony IST diversion program, (3) $32.8 million General Fund in 2021‑22—ramping up to $54.7 million General Fund in 2024‑25 and ongoing—to expand Community-Based Restoration programs, (4) $19.7 million General Fund in 2021‑22 and $28.8 million General fund in 2022‑23 and ongoing for DSH to contract with counties for additional Jail-Based Competency Treatment beds, and (5) $9.7 million General Fund in 2021‑22—ramping up to $14.7 million General Fund in 2024‑25 and ongoing—to expand mobile community treatment for felony ISTs.

Establishes IST Solutions Workgroup. The spending plan includes budget-related legislation establishing a workgroup—appointed by the CHHS Agency Secretary—that would develop short-, medium-, and long-term solutions to address the growing felony IST waitlist. These recommended solutions are required to be submitted to CHHS Agency by November 30, 2021. Furthermore, the spending plan includes budget-related legislation authorizing the Department of Finance to increase the DSH budget by up to $75 million General Fund in 2021‑22 to implement solutions identified by the workgroup. In the event the workgroup is unable to develop recommended solutions, budget-related legislation authorizes DSH to (1) discontinue admissions for certain patients, (2) impose patient reduction targets, or (3) charge a premium bed rate to counties that refer greater numbers of felony ISTs to the department.

Provides Funding for IST Re-Evaluations. The spending plan includes $12.7 million General Fund in 2021‑22—ramping down to $9.2 million General Fund in 2023‑24 and ongoing—to re-evaluate felony ISTs who have been waiting in county jail for 60 days or more for transfer to DSH. (According to the department, a significant number of felony ISTs regain their competency while in county jails.)

Other IST Issues. In addition to the funding provided for additional IST treatment capacity noted above, the spending plan includes budget-related legislation that (1) removes the financial liability of relatives of a DSH patient for care and treatment at a state hospital and (2) authorizes DSH to require that felony ISTs that are deemed unable to be restored to competency be returned to their referring county within ten days. This budget-related legislation also authorizes DSH to charge a daily bed rate to counties that do not take back these felony ISTs within the specified time frame.

Other Augmentations

The spending plan also includes various other General Fund augmentations for DSH. This includes (1) $131.3 million in 2021‑22 for deferred maintenance and construction projects, (2) $69.2 million in 2021‑22 for direct COVID-19 expenditures such as personal protective equipment and testing, (3) $16.5 million in 2021‑22—and $61.6 million total across four years through 2024‑25—for additional workers’ compensation claims related to COVID-19, (4) $29.3 million—ramping up to $66 million in 2025‑26 and ongoing—to implement new staffing standards across all state hospitals, and (5) $6.3 million in 2021‑22—and $2.2 million in 2022‑23 and 2023‑24—to contract for a statewide health care provider network for all state hospitals.

California Department of Public Health

The spending plan includes $4.7 billion from all fund sources for CDPH in 2021‑22. CDPH plays one of the state’s leading roles in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the onset of the pandemic, CDPH has received various state and federal allocations for response activities, which has caused the total level of spending in the CDPH budget to fluctuate significantly year over year. While the total CDPH budget averaged around $2.8 billion annually in each of the five years preceding the pandemic, it increased to $3.6 billion in 2019‑20 and further to $7.7 billion in the revised 2020‑21 budget before declining to $4.7 billion in 2021‑22. The General Fund provides $1.5 billion of the 2021‑22 CDPH budget, down from $2.9 billion in 2020‑21.

COVID-19 Response and Aftermath

The 2021‑22 spending plan for CPDH includes several spending items to continue support for the state’s COVID-19 response.

Support for Direct Response. The state spending plan includes cost estimates for COVID-19 response across numerous departments totaling $1.7 billion. Because needs could shift and change over the year, the amounts within each department are estimates, rather than set budget amounts. Please see our forthcoming consolidated post for additional information about budget actions related to the statewide COVID-19 response. Within the CDPH budget, the spending plan estimates costs of $1.08 billion to support the following activities.

- Testing—$625.2 million to support the state’s Valencia Branch Lab, specimen collection at state testing sites run by OptumServe, specimen transportation, and other related testing activities.

- Vaccinations—$295.2 million to distribute and administer vaccines.

- Hospital and Medical Surge—$60.8 million to ensure capacity to respond to virus surges.

- Other—$98.7 million for statewide response operations ($93.5 million), procurements ($2.8 million), and contract tracing and tracking ($2.4 million).

Other COVID-19-Related Augmentations. The spending plan includes several additional augmentations related to the state’s pandemic response and aftermath, totaling $10.1 million General Fund.

- Infectious Disease Modeling. Since February 2020, CDPH has been modeling COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and intensive care unit capacity. In July 2020, the University of California Office of the President established a COVID-19 Modeling and Analytics Consortium with input from CDPH. The spending plan includes $450,000 one time from the General Fund, available over two years, to support internal CDPH efforts as well as CDPH’s leading role in the consortium.

- COVID-19 Workplace Outbreak Reporting. The spending plan provides $677,225 ongoing from the General Fund to implement CDPH’s responsibilities pursuant to Chapter 84 of 2020 (AB 685, Reyes), which requires employers to report COVID-19 outbreaks (defined as three or more cases within a 14-day period) to their local public health department. CDPH’s role is to report this information by industry on its website.

- External Legal Challenges. The spending plan provides up to $6 million from the General Fund for external legal challenges, if needed.

Public Health Infrastructure

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed numerous shortcomings in state and local public health “infrastructure,” including under-staffing, insufficient in-house epidemiological capacity, under-resourced public health labs, and outdated data and information systems. The spending plan provides $3 million to assess the state’s pandemic response and identify what is needed in state and local public health departments going forward. While the spending plan does not include funding beginning in 2021‑22 for public health infrastructure, the budget agreement commits $300 million ongoing from the General Fund beginning in 2022‑23.

Other Public Health General Fund Augmentations

The spending plan includes numerous other augmentations in the CDPH budget for a variety of programs and activities.

California Reducing Disparities Project (CRDP). The spending plan includes $63.1 million one time from the General Fund available over four years to support phase 2 of the CRDP. CDPH’s Office of Health Equity administers this program, which began in 2009 with the goal of understanding differing mental health challenges within five specific populations (Latino, Asian and Pacific Islander, African American, Native American, and LGBTQ+) and to develop and evaluate mental health approaches and practices within these groups. There currently are 35 pilot projects underway with evaluations due in October 2022. Following evaluation, CRDP plans to ramp up these approaches in counties and expand services to additional special populations. The program has been funded in the past from Mental Health Services Act (MHSA) funds.

All Children Thrive Program. The spending plan provides $25 million one time from the General Fund available over five year for the All Children Thrive Program, administered through CDPH’s Injury and Violence Prevention Branch. This program began as a pilot three years ago after CDPH received $10 million from MHSA funds in the 2018‑19 budget. It seeks to work with cities and communities to reduce the prevalence and mitigate the effects of adverse childhood experiences.

Alzheimer’s Disease Awareness, Research, and Training. The spending plan includes $24.5 million one time from the General Fund available over three years to support several activities in CDPH’s Alzheimer’s Disease Program (as specified below). This funding builds on $3.1 million ongoing General Fund provided in 2018‑19 for research grants and $8 million General Fund, of which $3 million is ongoing, provided in 2019‑20 for local infrastructure, program grants, state operation, and the Governor’s Task Force on Alzheimer’s Prevention and Preparedness. In addition, this funding is part of a larger 2021‑22 effort related to implementation of the state’s Master Plan on Aging. Please see our forthcoming post on aging-related budget actions for more information.

- Public Awareness Campaign. $10 million for an Alzheimer’s and related dementias public awareness campaign that will be culturally competent and targeted toward at-risk populations and those currently living with these diseases.

- Statewide Standard of Dementia Care. $4.5 million to develop a model of care that involves physicians (and screening), a networked “hub-and-spoke” model that leverages California’s ten Alzheimer’s Disease Centers and incorporates family caregivers into patient planning.

- Research Grants. $4 million for grants focused on women and people of color (both of whom have a higher prevalence of dementias) and the LGBTQ+ community (which has been underrepresented in previous research).

- Caregiver Training and Certification Program. $4 million to develop a training and certification program for paid and unpaid caregivers and IHSS providers.

- California Blue Zone Challenge. $2 million for grants to cities and communities that have adopted or are willing to adopt dementia-friendly practices.

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) Wraparound Services. The spending plan provides $15 million one time from the General Fund available over five years to support wraparound services for individuals with ALS. This funding, which may be provided to the Golden West Chapter of the ALS Association, builds on $9 million General Fund provided in 2018‑19, which was available for three years.

Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Interventions. The spending plan includes $13 million ongoing from the General Fund for the prevention and control of STDs, HIV/AIDS, and hepatitis C. This funding builds on a 2019‑20 augmentation of $17 million ongoing from the General Fund ($7 million for STDs, $5 million for HIV/AIDS, and $5 million for hepatitis C).

California Parkinson’s and Other Neurological Diseases Registries. The spending plan provides $8.4 million one time from the General Fund available over four years to support the California Parkinson’s Disease Registry. Budget-related legislation removes the sunset date for this registry, extending it indefinitely. The funding provided also will support collection of data on other neurodegenerative diseases via a new Neurodegenerative Disease Registry Program. Budget-related legislation specifies that data collection must begin by January 1, 2023 and establishes a sunset date of January 1, 2028 for this program.

Behavioral Health Public Education Campaign. As part of the broader behavioral health initiative (please see the earlier section on Behavioral Health for a more in-depth discussion of the initiative), the spending plan provides $5 million General Fund in 2021‑22 and $50 million General Fund in 2022‑23 for a public education campaign to raise awareness for behavioral health issues. Total costs of this public education campaign are projected to be $100 million General Fund across the five years of the initiative.

Books for Low-Income Children. The spending plan includes $5 million one time from the General Fund for an early childhood literacy initiative. Specifically, CDPH will provide grants to local agencies that administer the Women, Infants and Children (WIC) program, which will use evidence-based approaches to select and distribute books to children in the WIC program.

Oral Health Program Guaranteed Funding. The spending plan provides $4.6 million General Fund to backfill declining Proposition 56 tobacco tax revenues for CDPH’s Oral Health Program. Budget act language specifies that the General Fund amount may be adjusted to ensure the program receives $30 million total from all funding sources.

Office of Suicide Prevention. The spending plan provides $2.8 million ongoing from the General Fund to establish and support the Office of Suicide Prevention in CDPH’s Injury and Violence Prevention Branch. The new office was authorized by Chapter 142 of 2020 (AB 2112, Ramos).

Biomonitoring Program Augmentation. The spending plan includes $2 million ongoing from the General Fund to continue to study effects of chemical exposure on Californians.

Sickle Cell Disease Supports. The spending plan includes $1.5 million one time from the General Fund for grants to community-based organizations who provide support to adults with sickle cell disease.

Funding to Implement Cosmetic Fragrance and Flavor Ingredient Right to Know Act. The spending plan includes $26,000 General Fund in 2021‑22 and $52,000 General Fund in 2022‑23 and ongoing to maintain the California Safe Cosmetics Program database and to implement Chapter 315 of 2020 (SB 312, Leyva), which increases the number and types of fragrances and flavor ingredients that must be reported to CDPH beginning January 1, 2022.

Emergency Medical Services Authority (EMSA)

The EMSA develops and implements emergency medical services in California, including regulation of emergency medical services personnel (such as emergency medical technicians), and aids in preparing for, coordinating, and supporting emergency medical response to disaster events. Like CDPH, EMSA has been playing an essential role in the state’s response to COVID-19 and its total budget has fluctuated year over year as a result of one-time COVID-19-related funding. The spending plan includes $85 million in total funds for EMSA in 2021‑22, down from $108.7 million in 2020‑21, but still above the $79.1 million provided in 2019‑20. The General Fund provides $59.9 million of the 2021‑22 funding amount.

COVID-19 Response and Aftermath

The 2021‑22 EMSA budget includes funding for direct COVID-19 response activities. The pandemic experience highlighted a number of resource needs at EMSA, which also are addressed in the spending plan.

Direct Response Expenditures. As noted earlier, the spending plan includes cost estimates for COVID-19 response across numerous departments totaling $1.7 billion. (Please see our forthcoming consolidated post on budget actions related to the statewide COVID-19 response for additional information.) Within the EMSA budget, the spending plan provides $17 million one time from the General Fund for estimated costs associated with ambulance transportation, medical personnel support, medical equipment and supplies, and other related emergency services infrastructure.

Medical Surge Staffing Program. The spending plan provides $1.4 million General Fund in 2021‑22 and $1.3 million General Fund in 2022‑23 and ongoing to manage medical surge staffing, including recruitment, on-boarding, training, and deployment of medical personnel as needed. The surge staffing program is comprised of the California Health Corps, the California Medical Assistance Team, and the Disaster Volunteers/Medical Reserve Corps.

Increased Emergency Preparedness and Response Capability. The spending plan includes $8.5 million General Fund in 2021‑22, $7.9 million General Fund in 2022‑23 and 2023‑24, and $1.6 million General Fund in 2024‑25 and ongoing to maintain and manage storage of equipment and supplies obtained during the COVID-19 pandemic; provide leadership and support at EMSA treatment sites and local emergency operations centers; and provide support for local disaster preparedness, response, mitigation, and recovery planning.

Regional Disaster Medical Health Response. The spending plan provides $365,000 ongoing from the General Fund for three new regional disaster medical health specialists (RDMHS) in three of the state’s six Governor’s Office of Emergency Services (Cal OES) Mutual Aid Regions. This augmentation results in each of the six Cal OES Mutual Aid Regions having two RDMHSs. Prior to 2020‑21, each region had one permanent RDMHS. The 2020‑21 budget provided $365,000 General Fund ongoing for three additional positions, while the current budget includes another $365,000 General Fund ongoing for another three positions, bringing the total up to 12.

Statewide Emergency Medical Services Data Solution. The spending plan provides $10 million one time from the General Fund to conduct project planning (using the state’s Project Approval Lifecycle process) for the California Emergency Medical Services Data Resources System. This system will be housed at EMSA and connect EMSA and the state’s 33 local EMSAs, allowing exchange of real-time emergency data and information (including from hospitals, emergency medical services agencies, and other health care providers). Currently, the approach for data collection and sharing is less systematic and run through multiple systems (one of which is housed at a local EMSA).

Other EMSA General Fund Augmentations