LAO Contacts

- Jennifer Pacella

- Deputy, Higher Education

- Jason Constantouros

- University of California

- Lisa Qing

- California State University

- California Student Aid Commission

- Paul Steenhausen

- California Community Colleges

January 26, 2022

The 2022‑23 Budget

Overview of the Governor’s

Higher Education Budget Proposals

- Introduction

- Overview

- Base Increases

- Performance Expectations

- Enrollment

- Tuition

- Facility Maintenance

Summary

Governor Has Multifaceted Higher Education Budget Package. The Governor’s 2022‑23 budget includes a total of $4.2 billion in new General Fund spending for the California Community Colleges (CCC), California State University (CSU), University of California (UC), and California Student Aid Commission. The Governor’s major proposals include approximately 5 percent base increases for each segment, enrollment growth, and one‑time funding for deferred maintenance projects. The Governor also recently announced entering multiyear agreements with each segment. Under his “compacts,” the universities would continue to receive annual 5 percent base increases through 2026‑27, linked with certain performance expectations. Additionally, UC would implement annual tuition increases beginning in 2022‑23. No outyear funding commitments are made for community colleges under the Governor’s “roadmap,” but they too would be expected to meet certain performance expectations.

Segments Face Specific Budget Challenges in 2022‑23. The community colleges face large pension rate increases (largely due to previously provided pension relief ending). All three segments face heightened salary and operating cost pressures given inflation has been increasing at a historically fast pace. Among the universities, we expect CSU to have the greater fiscal challenge, as the proposed base increases fall short of covering our projections of its core operating cost increases. In contrast, the proposed base increases for UC, when coupled with higher revenue from tuition increases, exceed projected core operating cost increases.

Governor’s Budgetary Approach Sidesteps Legislature. The Governor’s approach of working directly with the segments to build multiyear budget agreements and establish performance expectations has fundamental problems. The Legislature has authority to set the segments’ funding levels and decide what conditions to attach to that funding. Moreover, the Governor’s list of expectations is long, has odd inconsistencies across the segments, is missing key cost estimates, and lacks enforcement mechanisms.

Legislature Has Other Budget Options. We continue to recommend the Legislature link state funding increases with clear spending priorities. For the community colleges, the Legislature could consider redirecting some funds proposed for new activities toward addressing core underlying cost drivers, including rising pension costs. For CSU, the Legislature could consider a somewhat higher base increase for 2022‑23 among its spending priorities. For both CCC and CSU, the Legislature might explore tuition options as a way to avoid the steep spikes and long plateaus of past state tuition practices, expand budget capacity, create more predictability for students, and foster equity across student cohorts. For CSU and UC, the Legislature might consider extending the time the universities have to meet prior enrollment targets, as both universities experienced lower‑than‑anticipated enrollment in 2021‑22. Lastly, revenues permitting, the Legislature could provide more funding for maintenance projects, as all three segments have large maintenance backlogs.

Introduction

Brief Focuses on Three Public Higher Education Segments. This brief provides a high‑level summary and initial assessment of the Governor’s budget proposals for higher education. The brief focuses on the three public higher education segments—the California Community Colleges (CCC), the California State University (CSU), and the University of California (UC). The bulk of state higher education spending is for these segments. The brief also provides high‑level coverage of the California Student Aid Commission (CSAC), which administers most of the state’s college financial aid programs.

Brief Is Organized Around Major Budget Proposals. The first section of the brief provides an overview of the Governor’s higher education proposals. Each of the remaining five sections focuses on a key area of the Governor’s higher education budget package—base increases, performance expectations, enrollment growth, tuition, and facility maintenance, respectively. In each of these sections, we provide more detail on the Governor’s associated proposals and our initial assessment of them.

Additional Higher Education Budget Analyses Are Forthcoming. This brief is the first of several budget products relating to higher education that our office plans to release. Most notably, we will release separate briefs over the coming weeks that delve more deeply into the budget of each of the higher education segments. Our EdBudget website already has been updated to include many higher education budget tables reflecting the Governor’s proposals.

Overview

Governor Proposes Significant Increases in Ongoing Support for Higher Education. As Figure 1 shows, the Governor’s 2022‑23 budget includes a total of $20.3 billion in General Fund support for the three segments and CSAC. The proposed 2022‑23 funding level is $1.8 billion (9.6 percent) higher than the 2021‑22 level. All three segments and CSAC see year‑over‑year funding increases. CSAC sees the greatest increase (nearly 30 percent), followed by CSU (10 percent), UC (7.7 percent), and CCC with the lowest increase (4 percent). Of the $20.3 billion, $7.8 billion is Proposition 98 General Fund for CCC, with the remainder non‑Proposition 98 General Fund. (Unless otherwise noted, the CCC amounts cited throughout this brief reflect Proposition 98 General Fund, whereas the CSU, UC, and CSAC amounts reflect non‑Proposition 98 General Fund.)

Figure 1

Governor’s Budget Increases Ongoing Higher Education

Funding Significantly

Ongoing General Fund (Dollars in Millions)

|

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

Change From 2021‑22 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

CCCa |

$7,392 |

$7,528 |

$7,827 |

$299 |

4.0% |

|

CSUb |

4,026 |

4,597 |

5,064 |

467 |

10.2 |

|

UC |

3,465 |

4,010 |

4,318 |

308 |

7.7 |

|

CSAC |

1,994 |

2,356 |

3,059 |

703 |

29.8 |

|

Totals |

$16,878 |

$18,491 |

$20,268 |

$1,777 |

9.6% |

|

aReflects Proposition 98 General Fund that counts toward the minimum guarantee. The state may choose to spend a portion of this amount for one‑time purposes. bIncludes funding for pensions and retiree health. |

|||||

Total Core Funding Grows More Moderately. All three segments receive core funding from sources other than the state. For CCC, the largest nonstate fund source is local property tax revenue. For CSU and UC, the largest nonstate fund source is student tuition revenue. Accounting for all core funding gives a more comprehensive view of the segments’ funding situations. As Figure 2 shows, total core funding grows 4.4 percent for CCC, 6 percent for CSU, and 4 percent for UC. At CCC, total core funding grows at a slightly higher rate than state General Fund due to relatively high projected growth in local property tax revenue. At CSU and UC, total core funds grow more slowly than state General Fund, reflecting that student tuition revenue grows little at UC and not at all at CSU.

Figure 2

Total Core Funding Increases More Moderately

Ongoing Core Funds (Dollars in Millions)

|

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

Change From 2021‑22 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

CCC |

|||||

|

General Funda |

$7,392 |

$7,528 |

$7,827 |

$299 |

4.0% |

|

Local property taxa |

3,374 |

3,546 |

3,766 |

220 |

6.2 |

|

Student fees |

446 |

446 |

448 |

1 |

0.3 |

|

Lottery |

275 |

273 |

273 |

—b |

‑0.1 |

|

Subtotals |

($11,487) |

($11,794) |

($12,313) |

($519) |

(4.4%) |

|

CSU |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$4,026 |

$4,597 |

$5,064 |

$467 |

10.2% |

|

Student tuition and fees |

3,277 |

3,163 |

3,163 |

— |

— |

|

Lottery |

65 |

73 |

73 |

—b |

—b |

|

Subtotals |

($7,368) |

($7,833) |

($8,300) |

($467) |

(6.0%) |

|

UC |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$3,465 |

$4,010 |

$4,318 |

$308 |

7.7% |

|

Student tuition and fees |

4,935 |

5,295 |

5,443 |

148 |

2.8 |

|

Lottery |

43 |

51 |

50 |

—b |

‑0.1 |

|

Otherc |

395 |

395 |

395 |

— |

— |

|

Subtotals |

($8,838) |

($9,750) |

($10,207) |

($456) |

(4.7%) |

|

Totals |

$27,694 |

$29,378 |

$30,820 |

$1,442 |

4.9% |

|

aReflects Proposition 98 funds. bLess than $500,000 or 0.5 percent. c Includes a portion of overhead on federal and state grants and a portion of patent royalty income. |

|||||

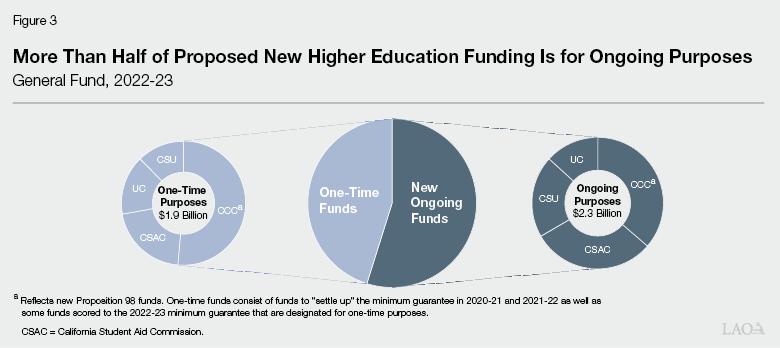

More Than Half of New Higher Education Spending Is Ongoing. As Figure 3 shows, 55 percent of the Governor’s proposed new spending in higher education is for ongoing purposes, with 45 percent for one‑time purposes. Of the $2.3 billion in new spending proposed for ongoing purposes, approximately two‑thirds is associated with CCC and CSAC proposals (combined), with the remaining one‑third associated with CSU and UC proposals (combined). Of the $1.9 billion in new spending proposed for one‑time purposes, approximately half is for CCC, with the remainder split between university and CSAC proposals.

Governor Has Many Higher Education Spending Priorities. Figure 4 shows, the Governor’s major ongoing and one‑time proposals for each segment and CSAC. Under the Governor’s budget, each of the three segments receives ongoing base increases, enrollment growth funding, and augmentations for foster youth support programs. In addition, CCC receives ongoing program augmentations for various purposes, including part‑time faculty health care and technology. For CSAC, the Governor’s budget includes ongoing augmentations for the revamped Middle Class Scholarship program (consistent with last year’s budget agreement) and higher Cal Grant caseload. Each of the three segments receives one‑time funding for facility maintenance projects. The universities also receive one‑time funding related to the Governor’s climate‑related priorities. The colleges receive additional one‑time funding for various purposes, including implementing student enrollment and retention strategies as well as developing a new common course numbering system. For CSAC, most of its one‑time initiatives, like its ongoing augmentations, implement budget agreements reached last year. In addition to all of these proposals, the Governor’s budget includes $750 million to implement the second year of the state’s three‑year initiative to create more affordable student housing units across the segments.

Figure 4

Proposed Higher Education Funding Increases

Are Spread Across Many Areas

General Fund Changes, 2022‑23 (In Millions)

|

CCCa |

CSU |

UC |

CSAC |

|

|

Ongoing Spending |

||||

|

Base increases for operations |

$462b |

$374c |

$201 |

— |

|

Enrollment growth |

25 |

81 |

99 |

— |

|

Foster youth programs |

10 |

12 |

6 |

— |

|

Health insurance for part‑time faculty |

200 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Student Success Completion Grantsd |

100 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Technology security |

25 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Middle Class Scholarship expansion |

— |

— |

— |

$515 |

|

Cal Grant caseload adjustments |

— |

— |

— |

188 |

|

Other |

21 |

—e |

3 |

—e |

|

Subtotals |

($843) |

($467) |

($308) |

($703) |

|

One‑Time Initiatives |

||||

|

Deferred maintenancef |

$388 |

$100 |

$100 |

— |

|

Climate‑action initiatives |

— |

133 |

185 |

— |

|

Student retention and enrollment strategies |

150 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Health care pathways for English learners |

130 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Common course numbering |

105 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Technology security |

75 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Transfer reform implementation |

65 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Learning‑Aligned Employment Programg |

— |

— |

— |

$300 |

|

Golden State Teacher Grantsh |

— |

— |

— |

98 |

|

Other |

70 |

1 |

10 |

1 |

|

Subtotals |

($983) |

($234) |

($295) |

($399) |

|

Totals |

$1,826 |

$701 |

$603 |

$1,102 |

|

a Reflects new Proposition 98 funds available over the 2020‑21 through 2022‑23 period. bIncludes cost‑of‑living adjustment for apportionments ($409 million) and select categorical programs ($53 million). cIncludes 5 percent base increase ($211.1 million) plus base increases for pension and retiree health care costs ($162.5 million). d Reflects caseload increase linked to CCC Cal Grant Entitlement Expansion enacted last year. eLess than $500,000. fCCC also may use proposed funding for water conservation projects, instructional equipment, and library materials, among various other facility and infrastructure purposes. UC and CSU also may use proposed funding for energy efficiency projects. gReflects second year of two‑year plan (per 2021‑22 budget agreement). hThe 2021‑22 Budget Act appropriated $500 million for this purpose. The budget act included language specifying that no more than $100 million was to be spent annually from 2021‑22 through 2025‑26. Amount shown reflects anticipated spending in year two. |

||||

Some Higher Education Spending Is Excluded From State Appropriations Limit. As Figure 5 shows, the Governor excludes a total of $1.2 billion in new higher education spending in 2022‑23 from the state appropriations limit (SAL). (The California Constitution imposes a limit on the amount of revenue the state can appropriate each year. The state can exclude certain capital outlay appropriations from the SAL calculation. In our report, The State Appropriations Limit, we cover SAL issues in more detail.) If the Legislature were to reject any of the specified higher education proposals, it very likely would need to replace the associated spending with proposals that still can be excluded from SAL or used for other SAL‑related purposes, thereby allowing the state to continue meeting its overall SAL requirement. Conversely, were the Legislature to augment funding for any of the higher education proposals shown in Figure 5, it then could consider rejecting a like amount of the Governor’s other SAL proposals (whether inside or outside of the higher education area).

No Proposals for Addressing Unfunded Retirement Liabilities or Providing Pension Relief. In recent years, the Governor has had various budget proposals relating to education pension funding. These proposals have included making supplemental payments toward pension systems’ unfunded liabilities as well as giving community college districts immediate pension relief by subsidizing their rates in 2019‑20, 2020‑21, and 2021‑22. Though employer contribution rates for most pension systems are expected to rise notably in 2022‑23, the Governor does not have any such proposals this year.

Figure 5

Several Higher Education Proposals

Are Excluded From SAL

New General Fund Exclusions, 2022‑23 (In Millions)

|

Proposal |

|

|

Affordable student housing grant program |

$750 |

|

CCC deferred maintenancea |

109 |

|

CSU deferred maintenanceb |

100 |

|

UC deferred maintenanceb |

100 |

|

CSU Bakersfield Energy Innovation Centerc |

83 |

|

CSU University Farms facilities and equipmentc |

50 |

|

Total |

$1,192 |

|

aReflects Proposition 98 General Fund. In addition to amount shown, the Governor excludes an associated $182 million in 2021‑22 and $97 million in 2020‑21. CCC also may use proposed funding for water conservation projects, instructional equipment, and library materials, among various other facility and infrastructure purposes. bFunds also may be used for energy efficiency projects. cThe Governor classifies this proposal as a climate‑action initiative. |

|

|

SAL = state appropriations limit. |

|

Base Increases

Governor Proposes Budget‑Year Base Increases for Each Segment. The Governor proposes base increases for each of the segments—5.33 percent for CCC and 5 percent for CSU and UC. In dollar terms, these augmentations amount to an additional $409 million in ongoing CCC support, $211 million for CSU, and $201 million for UC. (In addition to this base increase, the Governor’s budget provides CSU with $162 million ongoing for its retiree health care and pension costs.) Though the CCC base increase is connected to a measure of inflation consistently used by the state to adjust apportionment funding, the university base increases are not linked with any such measure. The universities’ augmentations also are not linked to any specific, documented operating cost increases. The three segments can use base increases for any operating cost, including employee salaries and benefits, utilities, supplies, and equipment.

Governor Also Proposes Future Base Increases for the Universities. The Governor recently announced his interest in establishing multiyear “compacts” with CSU and UC. Under these compacts, the Governor proposes to provide CSU and UC with 5 percent annual base increases over each of the next five years. Whereas the Governor proposes enrollment growth funding on top of the base increases in 2022‑23, the universities would be required to accommodate 1 percent annual enrollment growth within their base increases over the remainder of the compact period (2023‑24 through 2026‑27). For CCC, the Governor recently announced his interest in establishing a multiyear “roadmap,” but this roadmap does not commit to future base increases for the colleges. Future base funding would be specified in subsequent Proposition 98 packages.

Community Colleges’ Base Increase Needed Partly for Pension Cost Increases. To get a sense of how far the Governor’s proposed base increases would stretch, we compare them to the segments’ key operating costs. For the community colleges, the Governor’s proposed base increase is substantial. A 5.33 percent cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA) for apportionments would be among the highest COLA rates the colleges have ever received. Community colleges’ pension rates, however, also are increasing in 2022‑23 at an unusual pace (approximately 2 or 3 percentage points, depending upon the pension system). The relatively high rate increases are due to previously provided state pension relief ending, combined with long‑term plans by the pension systems to continue paying down large unfunded liabilities. (The funding conditions of state pension systems improved with stock market gains the past couple of years, but sizeable unfunded liabilities remain.) Though the state’s pension boards will not adopt final rates until spring 2022, we expect CCC will need to use approximately 40 percent (roughly $170 million) of the proposed apportionment COLA to cover higher pension costs. Out of the remaining 60 percent, colleges must cover any health care cost increases as well as increases in utilities and other operating expenses and equipment (OE&E). While most community colleges likely will have sufficient funds to offer some level of salary increases, such increases might not be able to keep pace with inflation, given inflation also has been increasing at a historically fast pace.

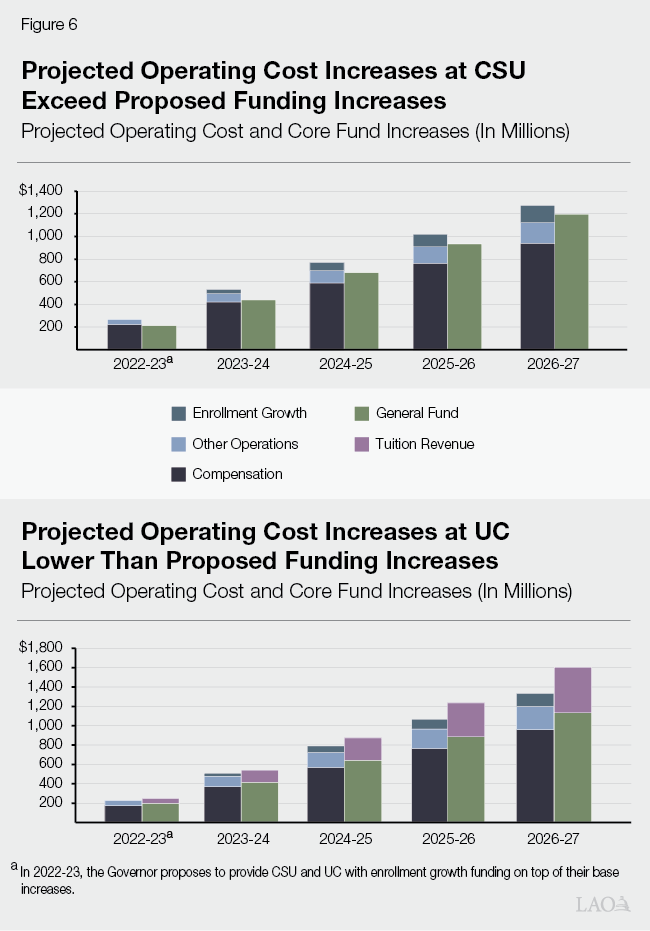

Unlike UC, the Proposed Budget‑Year Base Increase for CSU Falls Short of Projected Operating Costs. We also compare the Governor’s proposed base increases for the universities to their operating cost increases. For this analysis, we assume annual salary growth of approximately 3 percent, growth in annual health care costs of 5 percent, and growth in OE&E of approximately 3.5 percent, together with estimated changes in CSU’s and UC’s pension and debt‑service costs. For 2022‑23, projected operating cost increases exceed CSU’s ongoing base increase by more than $50 million. In contrast, projected operating cost increases at UC are lower than the Governor’s proposed base increase by about $20 million.

In Outyears, Additional Tuition Revenue Also Puts UC in More Advantageous Position. Figure 6 compares how CSU and UC fare across all the years of the proposed compact (2022‑23 through 2026‑27). At CSU, the Governor’s proposed base increases consistently fall short of meeting projected cost increases (including the proposed 1 percent enrollment growth). In contrast, at UC, the Governor’s proposed base increases consistently exceed projected cost increases (including the proposed 1 percent enrollment growth). The main difference between the universities is that UC raises tuition revenue above the Governor’s proposed base General Fund augmentation. Without this additional tuition revenue, UC too would fall short of meeting projected cost increases.

Legislature Has Various Budget Options. Given the implications of the above analyses, the Legislature may want to consider some different budget options than those proposed by the Governor. Overall, we continue to recommend the Legislature take a more transparent budget approach—one that links state funding increases with clear spending priorities. For the community colleges, the Legislature could consider redirecting some of the funds the Governor proposes for new activities, including new one‑time activities, toward addressing colleges’ core underlying cost drivers, including rising pension costs and unfunded pension liabilities. For CSU, the Legislature could consider a somewhat higher base increase for 2022‑23 among its spending priorities, if revenues allow. In the outyears, the Legislature could consider the potential benefits of tuition increases in helping all the segments cover core cost drivers. (We discuss tuition issues in more depth later in this brief.)

Compacts Historically Have Not Been Accurate Guide for the Future. We caution the Legislature against putting too much stake in the Governor’s outyear commitments to the universities. Former governors rarely been able to sustain their compacts over time. In some cases, changing economic and fiscal conditions in the state have led governors to suspend their compacts. For example, in 2009‑10, Governor Schwarzenegger proposed eliminating all of his higher education compact funding “as part of solutions to address the fiscal crisis.” Though compacts sometimes are thrown off course by adverse state fiscal conditions, they also can be altered due to improved state fiscal conditions. For example, in 2015‑16—a year of notable state revenue growth—the Legislature approved ongoing funding increases beyond those proposed under Governor Brown’s compact.

Performance Expectations

Governor Sets Many Expectations for the Segments. The Governor’s 2022‑23 Budget Summary specifies a total of 55 expectations for the segments (15 for CCC, 22 for CSU, and 18 for UC). As part of his multiyear CCC roadmap and university compacts, the segments would have up to five years to meet most of the expectations. As Figure 7 shows, these expectations focus on student access, student success and equity, college affordability, intersegmental collaboration, workforce alignment, and online education. Some of the expectations build off existing initiatives developed by the segments. For example, all the segments have initiatives with graduation and equity goals that are the same or similar to those in the Governor’s compact. Other expectations, however, are driven primarily by the administration. For example, the Governor would like the universities to use a common integrated admissions platform, a common learning management system, and a common tool for measuring equity gaps. Though the Governor lists his expectations in his budget summary, he does not intend to have them codified. Moreover, to date, the administration has set forth no specific repercussions were a segment to miss one or more of the expectations. The Department of Finance (DOF) indicates that the administration reserves discretion to propose smaller future base increases were a segment not to demonstrate progress in meeting its expectations.

Figure 7

Governor Has Long List of Higher Education Expectations

Expectations Specified in Governor’s 2022‑23 Budget Summary

|

CCC |

CSU |

UC |

|

|

Access |

|||

|

Increase resident undergraduate enrollment annually |

X |

X |

|

|

Maintain minimum proportion of new transfer students |

X |

X |

|

|

Increase graduate enrollment |

X |

||

|

Student Success and Equity |

|||

|

Increase student completions rates by specified amounts |

X |

X |

X |

|

Decrease average units to completion and time to completion |

X |

||

|

Increase number of students transferring to CSU and UC |

X |

||

|

Annually publish specified student completion rates |

X |

||

|

Advance re‑enrollment campaigns and establish retention goals |

X |

||

|

Expand credit opportunities in intersessions and summer sessions |

X |

||

|

Provide every student access to digital degree planner |

X |

||

|

Close specified achievement gaps for underrepresented and Pell Grant students |

X |

X |

X |

|

Close equity gaps in dual enrollment programs |

X |

||

|

Affordability |

|||

|

Create debt‑free pathway for every undergraduate student |

X |

||

|

Reduce textbook and instructional material costs |

X |

X |

|

|

Increase proportion of new tuition revenue set aside for financial aid |

X |

||

|

Include student housing projects in capital campaigns |

X |

X |

|

|

Intersegmental Collaboration |

|||

|

Fully participate in implementation of the Cradle‑to‑Career data system |

X |

X |

X |

|

Support campuses in adopting a common learning management system |

X |

X |

X |

|

Develop common tool to identify trends to address equity gaps |

X |

X |

X |

|

Support efforts to establish common integrated admissions platform |

X |

X |

X |

|

Workforce Alignment |

|||

|

Increase percentage of high school students completing a semester of college credit through dual admission |

X |

||

|

Establish baseline for prior‑learning credit and launch new direct‑assessment competency‑based education programs |

X |

||

|

Increase percentage of completing students earning a living wage |

X |

||

|

Establish/expand programs in early education, education, health care, and climate action fields |

X |

||

|

Establish coordinated educational pathways for high school students in education, health care, technology, and climate action fields |

X |

X |

X |

|

Develop new transfer pathways in education, health care, technology, and climate action fields |

X |

X |

|

|

Increase number of early education degree pathways available to students |

X |

||

|

Increase number of students enrolling in early education, education, STEM, and social work fields |

X |

||

|

Increase number of students graduating with early education, education, STEM, and academic doctoral degrees |

X |

||

|

Establish goal to enable all students to participate in at least one semester of undergraduate research, internships, or service learning |

X |

X |

|

|

Double opportunities for students who want research assistantships or internships |

X |

||

|

Online Education |

|||

|

Increase online course offerings above pre‑pandemic levels |

X |

X |

|

|

Increase concurrent online enrollment |

X |

||

|

Expand digital tools for students to access online learning materials |

X |

||

|

STEM = science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. |

|||

Odd Inconsistencies in Expectations Across Segments. As described by DOF, the administration established his expectations in coordination with each of the three segments individually. This segment‑specific development of the expectations might account for the odd inconsistencies evident in the list. One of the major oddities is that some expectations apply to only one rather than all of the segments. For example, the Governor expects only UC to offer its undergraduates a debt‑free college pathway by 2030. Only CSU is expected to establish retention goals for continuing students, and only CCC is expected to increase the percentage of completing students who go on to earn a living wage. Another oddity is that some of the expectations are much more ambitious for some segments. For example, the Governor has no expectation that community colleges reduce their textbook and instructional material costs, whereas he expects CSU “to reduce the cost of instructional materials by 50 percent by 2025” and UC “to eliminate textbook costs for all lower‑division undergraduate courses.”

Key Cost Data Is Missing. Typically, when the state wants to accomplish a policy objective, it specifies the objective in statute, estimates the cost of achieving the objective, and provides funding to meet the objective. In contrast, the Governor’s 55 expectations are not linked directly with cost estimates. For example, the Governor provides no estimate of the amount it would cost UC to provide every undergraduate a debt‑free education pathway or the amount it would cost CSU to ensure “every student has access to appropriate technology for online learning.” Especially given some of the expectations likely have high costs, the segments could face difficult fiscal choices in meeting expectations within their base funding allotments. These choices could become even more difficult were a segment to have its base funding reduced unexpectedly due to not meeting one or more of its goals. Moreover, some of the choices the segments ultimately might make could run counter to legislative priorities.

Compact Undermines Legislative Authority. Though the inconsistencies in the expectations and lack of cost data are troubling, more troubling is the Governor’s overall approach of building a compact. The Governor’s approach of working directly with each of the segments to build multiyear budget agreements and establish performance expectations has the fundamental problem of sidestepping the legislative branch of government. The Legislature is responsible both for enacting annual state budgets and crafting policy aligned with those budgets. Throughout the upcoming 2022‑23 budget process (as with any annual budget process), the Legislature will set the segments’ funding levels and decide what conditions to attach to that funding. Moreover, the Legislature can identify areas of common interest with the Governor and segments and then work with them collaboratively over the coming months to make progress in these areas.

Linking Expectations to Appropriate Repercussions Requires More Deliberation. If the Legislature is interested in creating additional ways to improve the segments’ performance through stronger fiscal hooks, then it likely would need to dedicate substantial time and deliberation to the endeavor. Over the years, the Legislature has considered many ways of incentivizing the segments to improve their outcomes, ranging from requiring performance reporting to creating categorical programs linked to specific improvement objectives to developing new funding formulas with performance components. One of the more notable and recent of these efforts occurred in 2018‑19 when the Legislature adopted a new budget formula that linked a portion of apportionment funding to community colleges’ performance. As with this new budget formula, past legislative efforts have entailed complex deliberations about what performance to measure, how to measure it, what benchmarks to set, and what enforcement mechanisms to institute. The Governor’s CCC roadmap and university compacts foray into some of these areas (such as what to measure), but other areas (such as enforcement and fiscal repercussions) remain unaddressed.

Enrollment

Governor Has 2022‑23 Enrollment Growth Proposals for Each Segment. For CCC, the Governor’s budget includes $25 million to cover 0.5 percent systemwide enrollment growth, equating to 5,500 additional full‑time equivalent (FTE) students. The Governor’s budget includes $81 million (above base funding) for CSU to serve an additional 9,434 FTE resident undergraduate students, reflecting a 2.8 percent increase, and it includes $68 million (also above base funding) for UC to serve an additional 6,230 FTE resident undergraduate students, reflecting a 3 percent increase. The university proposals are intended to align with enrollment growth expectations set forth in the 2021‑22 Budget Act.

All Three Segments Are Seeing Lower‑Than‑Anticipated Enrollment in 2021‑22. As context for understanding the Governor’s enrollment proposals, we looked back at enrollment trends over the past several years. As Figure 8 shows, community college enrollment has continued to drop throughout the pandemic. These drops have been attributed to various factors, including more parents staying home to provide child care, public health concerns, and disinterest among some students to taking courses online, as well as rising wages and an improved job market. In contrast to community colleges, the universities did not experience enrollment declines in 2020‑21. They too, however, are expected to experience declines in 2021‑22. The decline is expected to be especially notable at CSU—with enrollment among its new freshmen, transfer students, and continuing students all down.

Figure 8

Drops in 2021‑22 Enrollment Across All Segments Likely Linked to Pandemic

Resident Undergraduate Full‑Time Equivalent (FTE) Students

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

|

|

CCCa |

1,188,872 |

1,177,205 |

1,149,078 |

1,062,572 |

1,009,443b |

|

Change from prior year |

‑11,666 |

‑28,128 |

‑86,506 |

‑53,129 |

|

|

Percent change from prior year |

‑1.0% |

‑2.4% |

‑7.5% |

‑5.0% |

|

|

CSU |

349,004 |

348,210 |

352,693 |

353,262 |

340,470 |

|

Change from prior year |

‑794 |

4,483 |

569 |

‑12,792 |

|

|

Percent change from prior year |

‑0.2% |

1.3% |

0.2% |

‑3.6% |

|

|

UC |

185,416 |

189,489 |

193,792 |

200,075 |

199,358 |

|

Change from prior year |

4,073 |

4,303 |

6,283 |

‑717 |

|

|

Percent change from prior year |

2.2% |

2.3% |

3.2% |

‑0.4% |

|

|

aReflects total credit and noncredit FTE students. bReflects LAO estimate. Preliminary data for 2021‑22 are not yet available. Early signals indicate CCC enrollment continues to drop, potentially more than is shown here. |

|||||

Pandemic Continues to Make Enrollment Planning More Challenging. When the Legislature set enrollment targets for the segments last year, it did not expect to see enrollment levels continuing to be soft at all the segments. At the time, many legislators expected enrollment would rebound in 2021‑22 with the resumption of on‑campus operations. The enrollment drops the segments are experiencing in 2021‑22 could be an indication of the continuing challenge in managing enrollment during unusual times. As the Legislature assesses the Governor’s enrollment proposals and considers its enrollment priorities for the coming year, we encourage it to keep in mind the heightened uncertainty of these times, along with the segments’ accompanying enrollment planning challenges.

Universities Could Need More Time to Meet Enrollment Targets. In response to the heightened uncertainty, the Legislature could consider giving the universities an additional year to meet the enrollment targets set last year. The Legislature also could specify a target enrollment level for each university. Last year, the state took a different approach by setting the baseline year and growth expectation but not the total expected enrollment level. This approach can lead to unintended consequences. For example, if enrollment growth for CSU were measured from its lower 2021‑22 level, then the Governor’s proposal would result in CSU receiving an augmentation even though it would be expected to serve fewer students in 2022‑23 than it had a few years earlier. Setting a target enrollment level (rather than only a growth target) would eliminate such potential ambiguity for both the segment and the state while providing greater assurance that state enrollment growth funding would be used to enroll additional students beyond the level already recognized by the state. (If community colleges do not meet their enrollment target and the associated funds are not needed for certain other state‑specified purposes, then the funds revert.)

Tuition

Governor’s Compact Assumes UC’s Tuition Plan, Does Not Have Similar Plans for Other Segments. The Governor’s compact with UC assumes the university implements the new tuition policy recently adopted by the Board of Regents. Beginning in 2022‑23, this policy applies annual tuition increases to all academic graduate students and uses a cohort model in applying higher charges to incoming undergraduate students, with charges held flat for continuing undergraduate students. Annual tuition increases are tied to inflation (the California Consumer Price Index), except undergraduate charges would increase somewhat more than inflation over the 2022‑23 through 2025‑26 period, as the cohort‑model phases in. For CSU, the Governor’s budget assumes no tuition increase in 2022‑23. Similarly, the Governor proposes no tuition (enrollment fee) increase for community colleges.

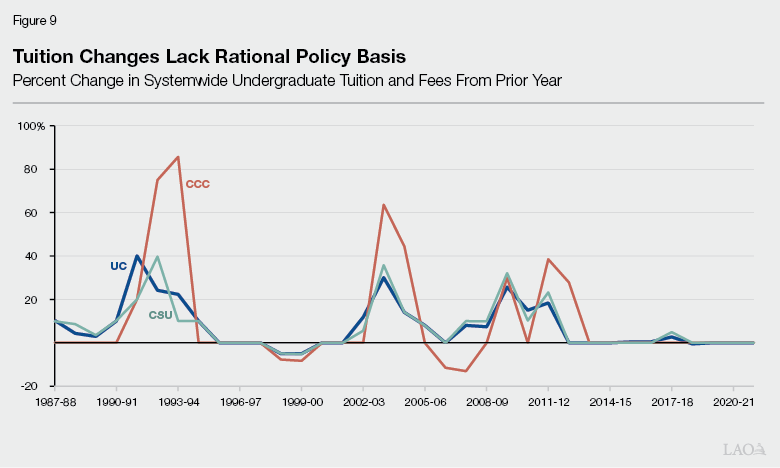

UC’s Tuition Plan Reflects More Rational Policy Than State’s Past Tuition Practices. Implementing UC’s new tuition policy would be a notable departure from previous tuition practices. As Figure 9 shows, the state’s experience to date has been to have steep tuition increases during economic recessions (in the early 1990s, early 2000s, and Great Recession period) while leaving tuition flat throughout most years of economic recoveries. Such practices tend to work counter to families’ fiscal situations, with household income tending to weaken during recessions and improve during recoveries. As a result of such practices, student cohorts enrolling in college during recessions tend to pay a higher share of their education costs than student cohorts enrolling during recoveries. By raising charges more gradually and predictability, UC’s new tuition policy has the potential to overcome the main weaknesses of these previous state tuition practices.

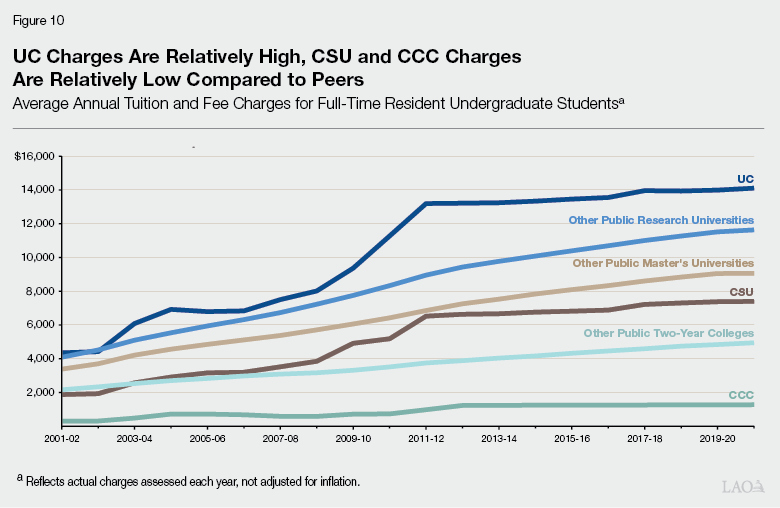

UC Tuition Relatively High, CSU and CCC Tuition Relatively Low Compared to Peers. Although the Governor’s compact assumes tuition increases only for UC, UC already has relatively high tuition charges compared to other public research universities. As Figure 10 shows, UC’s undergraduate tuition level 20 years ago was about the same as other public research universities in the country, but began diverging during the Great Recession notably and remains higher. In 2020‑21, its annual undergraduate tuition level was approximately $2,500 (20 percent) higher than the average of its peer institutions. By comparison, CSU has remained below other public master’s universities, with its tuition level in 2020‑21 approximately $1,600 (18 percent) lower than that of its peers. CCC tuition has been and remains much lower than other public two‑year colleges, with the average tuition of its peers about four times higher.

Encourage Legislature to Explore Tuition Policy Options for CSU and CCC. The state might explore tuition policy options for CSU and CCC for two reasons. One reason is to have a more rational tuition policy that avoids the tuition spikes and plateaus that have characterized state tuition practices over the years. A more rational policy could raise tuition charges gradually and predictably, with tuition charges potentially held flat only during economic recessions when family incomes are stagnating or declining. Another reason to consider a tuition policy for CSU and CCC would be to expand their budget capacity. With additional tuition revenue, CSU and CCC could cover additional high priorities—potentially allowing for more enrollment growth, graduation initiatives, and student support programs. Given the time needed to consult with affected groups and develop new policies, beginning to explore tuition options now could allow the segments to put any new policies in place for the 2023‑24 academic year.

Facility Maintenance

Governor’s Budget Funds Deferred Maintenance Projects at All Three Segments. The Governor proposes to provide CCC with $388 million one time for facility maintenance, water conservation projects, instructional equipment, and library materials, among various other facility and infrastructure purposes. The Governor proposes to provide CSU and UC each $100 million one time for deferred maintenance and energy efficiency projects.

Segments Have Large and Still Growing Deferred Maintenance Backlogs. Over the past seven years, the state has designated some one‑time funding for deferred maintenance projects at the segments. From 2015‑16 through 2021‑22, the state provided more than $2 billion for these projects. Despite this state funding, the segments’ backlogs continue to grow. CSU’s backlog, for example, grew from an estimated $3.6 billion in 2016‑17 to $5.8 billion in 2021‑22. Currently, all three segments report sizeable backlogs. Beyond CSU’s $5.8 billion backlog, CCC reports a $1.2 billion backlog and UC reports a $7.3 billion backlog.

Legislature Could Prioritize Deferred Maintenance for More Funding. Providing funding for deferred maintenance projects helps to address a large and growing problem in the state. As the Legislature assesses the Governor’s other one‑time proposals and receives updated revenue information in May, it could consider providing more funding for this purpose. (Funding for these types of projects generally is SAL‑excludable.) If the Legislature were to consider providing more funding for deferred maintenance, it could weigh the needs of the higher education segments against those of other state agencies. Many other state agencies also have large maintenance backlogs (though departments vary in their documentation of deferred maintenance needs).