LAO Contact

February 18, 2022

The 2022‑23 Budget

Analysis of Child Support Program Proposals

Summary

In this brief, we asses three Governor’s budget proposals related to the state child support program.

Allow Full Pass‑Through of Past‑Due CalWORKs Recoupment Payments to Former CalWORKs Families. Under federal law, when a parent applies for California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) cash aid (and is not living with the other parent), they generally are required to open a child support case and sign over a portion of their child support payments to the state. This is because a portion of their monthly support payments are retained by the state as a way to pay back the total government costs for the cash aid the family received under the CalWORKs program. This process of retaining the child support as reimbursement for CalWORKs is referred to as CalWORKs recoupment. The CalWORKs recoupment payments are roughly split between the state (50 percent), counties (5 percent), and federal government (45 percent).

The Governor’s budget proposes to allow low‑income families who formerly received CalWORKs cash aid to keep the payments (collected by the child support program) that are currently used to pay back the government for the CalWORKs cash aid they previously received. The federal government would not require the state to backfill the lost funds that would have gone to the federal government if the payment had not been passed through to the family. The Governor’s proposal reflects one of many ways the state could pass through additional payments to low‑income families. The Legislature may want to select a policy framework that reflects its goals for assisting families participating in the child support program. Alternative policy options include increasing the pass‑through amount (up to the full payment amount) for current CalWORKs families, which could be done in addition to the Governor’s budget proposal. Overall, the Legislature may want to consider the amount of additional funding needed to increase pass‑through amounts for both current and former CalWORKs families, how quickly could each policy change be implemented, and how changes may possibly impact eligibility for CalWORKs and other state programs.

Provide Additional LCSA Administrative Funding. The Governor proposes an additional wave of increased administrative funding for local child support agencies (LCSAs), which is intended to build upon the General Fund increase provided in 2021‑22. We recommend the Legislature withhold action on any future LCSA funding increases until the administration revises its funding methodology to maximize program efficiencies and accurately reflect actual LCSA funding needs in light of recent and future program changes.

Statutory Changes to Comply With Recent Federal Reforms. The administration proposes language to align child support program rules with recent federal reforms. We provide initial questions and comments to assist the Legislature in assessing the language.

Background

What Is the Child Support Program? The child support program is a federal‑state program that establishes, collects, and distributes child support payments to enrolled parents with children. These tasks include locating difficult to find parents; certifying paternity; establishing, enforcing, and modifying child support orders; and collecting and distributing payments. In California, the child support program is administered by 47 county and regional local child support agencies (LCSAs), in partnership with local courts. Local program operations are overseen by the state Department of Child Support Services (DCSS).

Administration Created LCSA Administrative Funding Methodology in 2019‑20. In 2019‑20, the administration created a new LCSA funding methodology. The intent of the administration’s LCSA funding methodology was to estimate the amount of funding each LCSA needed based on target staffing levels. The administration’s calculation of target staffing levels primarily was based on averaging enforcement, management, and support staff levels in place as of 2018. A small portion of the calculated target staffing levels was informed by a 2018 workload study conducted in 15 LCSAs. Those LCSAs with funding below these target levels were considered “underfunded,” while those with funding above these target levels were considered “overfunded.” Since 2019‑20, the administration has updated its total funding estimate every year to reflect the most recent caseload levels and LCSA salary and benefit costs (which are negotiated and established by counties). As a result of the methodology, estimated LCSA funding needs increase (or decrease) when caseload or LCSA salary and benefit levels increase (or decrease). Our initial assessment of the funding methodology is provided in The 2019‑20 Budget: Analysis of Proposed Increase in State Funding for Local Child Support Agencies.

Majority of Child Support Cases Are Required to Enter Program as a Result of CalWORKs Participation. In federal fiscal year (FFY) 2020, about 75 percent of child support cases generally reflected families that currently or formerly received cash aid from the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program. Under federal law, when a parent applies for CalWORKs cash aid (and is not living with the other parent), they generally are required to open a child support case and sign over a portion of their child support payments to the state. This is because a portion of their monthly support payments are retained by the state as a way to pay back the total government costs for the cash aid the family received under the CalWORKs program. This process of retaining the child support as reimbursement for CalWORKs is referred to as CalWORKs recoupment. The CalWORKs recoupment payments are generally split between the state (roughly 50 percent), counties (roughly 5 percent), and federal government (roughly 45 percent). The state’s share of CalWORKs recoupment is deposited into the General Fund as revenue. The administration projects that about $340 million would be collected for public assistance cases in 2022‑23, which under current law would be roughly distributed across the state ($170 million), counties ($20 million), and federal government ($150 million). (The Governor’s budget proposes to distribute a portion of these payments to families instead of the government, which we describe in more detail later in the brief.)

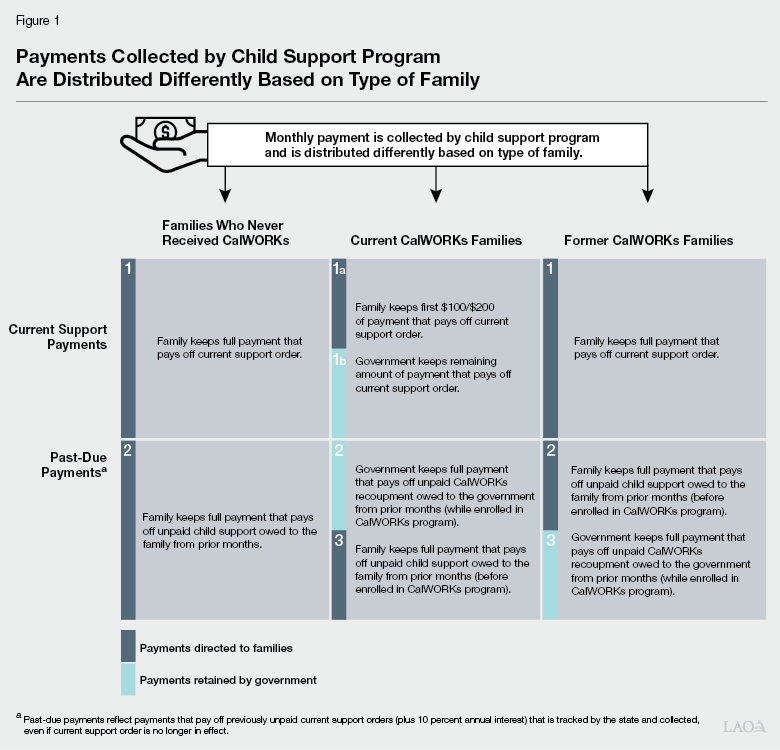

If Currently Owed Support Is Not Paid, Debt Is Created and Tracked. The child support program collects two main types of monthly payments: current support payments (required monthly payments under an active current child support order established by a court) and past‑due payments (payments that pay off previously unpaid current support [plus 10 percent annual interest] that is tracked by the state and collected, even if a current support order is no longer in effect). Figure 1 shows that whether these two payments are directed to the family or government depends on whether the family is currently, or has ever, received CalWORKs. In general, current support and past‑due payments are sent to families first when families do not receive CalWORKs cash aid. However, when a family receives CalWORKs cash aid, current support and past‑due payments are directed to the government first (with the exception of a portion of current support payments going to the family with the remaining amount being retained by the government). We describe the payment distribution rules for each type of family in more detail below.

- Never Assisted Families Keep All Current Support and Past‑Due Payments. A family who never received CalWORKs cash aid keeps the full amount of current child support payments. To the extent that the current support payment falls below the ordered amount, the state tracks this unpaid amount and continues to seek payment. The family keeps the full amount of all past‑due payments.

- Current Support and Past‑Due Payments for Current CalWORKs Families Are Typically Retained by the Government First. As previously mentioned, a family who currently receives CalWORKs cash aid (referred to as a current CalWORKs family) is required to sign over their child support payments to the state, however, a portion is retained by families. Specifically, up to $100 of the current support payment is directed or “passed through” to families with one child every month (increasing to $200 for families with two or more children). The remaining portion of the current support payment is retained by the government as reimbursement for CalWORKs cash aid. If only a partial payment is made for a current support order, the amount of unpaid support is tracked by the state as government‑owed debt or past‑due CalWORKs recoupment payment. Any past‑due payments collected by the child support program (while the family is participating in CalWORKs) goes to the government first to pay off past‑due CalWORKs recoupment. Once the government‑owed debt is paid in full, past‑due payments are then directed to the families to pay off any pre‑existing family‑owed child support debt (this would be from missed child support payments that accrued prior to the family receiving CalWORKs aid).

- Current Support and Past‑Due Payments for Former CalWORKs Families Are Directed to Families First. Once a family exits CalWORKs (referred to as a former CalWORKs family), they begin to receive the full amount of current support payments. Additionally, any payments towards past‑due amounts are first directed to families to pay off any family‑owed debt. Past‑due CalWORKs recoupment is paid last. Under current law, past‑due CalWORKs recoupment payments are fully retained by the government.

State Has Discretion Over What Amount of Payments Are Passed Through to Current and Former CalWORKs Families. While current CalWORKs families can receive $100 (or $200 for a family with two or more children) of a current child support payment, the state could choose to pass through a greater amount of payments (up to the full amount of the payment). To do so, California would have to pay back, or backfill, the federal government for the amount of the pass‑through payment that would have otherwise gone to reimburse the federal share of CalWORKs recoupment (45 percent of the remaining payment). (The federal government does not require repayment of its share of the $100/$200 pass through.) In the case of former CalWORKs families, the federal government allows the state to fully pass through to families the payments that would have been retained by the government to cover past‑due CalWORKs recoupment. In these cases, the federal government would not require the state to backfill the lost funds that would have come if the payment had not been passed through to the family. Despite this allowance, California continues to retain the full amount of payments intended to cover past‑due CalWORKs recoupment for formerly assisted CalWORKs families. (We discuss this in more detail in a later section.)

Overview of Governor’s Budget

The Governor’s budget proposes $364.7 million General Fund ($1.2 billion total funds) in 2022‑23 for DCSS, which is about a 6 percent increase over estimated 2021‑22 funding levels—$344.7 million General Fund ($1.1 billion total funds). This increase is due to the Governor’s proposal to increase administrative funding for LCSAs by $20.1 million General Fund in 2022‑23. Additionally, the Governor’s budget assumes about a $40 million decrease in the state’s share of primarily CalWORKs recoupment in 2022‑23 (from an estimated $160 million in 2021‑22 to $120 million in 2022‑23). The decrease in the state’s share of primarily CalWORKs recoupment largely is due to the Governor’s budget proposal to pass through payments that otherwise would have been used to cover past‑due CalWORKs recoupment to former CalWORKs families instead. Below, we provide more detail on each budget proposal and, where relevant, describe alternative approaches for Legislative consideration.

Allow Full Pass‑Through of Past‑Due CalWORKs Recoupment Payments to Former CalWORKs Families

LAO Bottom Line: Consider Selecting Pass‑Through Policy Framework That Aligns With Legislative Goals. As described earlier, when a past‑due CalWORKs recoupment payment is collected on behalf of a former CalWORKs family it is fully retained by the government as a reimbursement for previously provided CalWORKs cash aid. The Governor’s budget proposes to fully pass through these payments to the family instead. The existing pass‑through policy for current CalWORKs families would remain unchanged. The Governor’s budget proposal reflects one of many pass‑through policies the Legislature could consider. The Legislature may wish to consider the benefits and trade‑offs of the various policy options and select a pass‑through policy framework that aligns with its goals.

Background

State Collects Payments to Cover Past‑Due CalWORKs Recoupment in Former CalWORKs Cases. As previously mentioned, in the case of former CalWORKs families, when a child support payment is made, it is first applied to current support orders and child support debt owed to the family. As a result, past‑due CalWORKs recoupment owed to the government is the last to be paid. The state continues to seek payment on any past‑due balance even if a current support order is no longer in effect.

Federal Government Allows the State to Fully Redirect Past‑Due CalWORKs Recoupment Payments to Former CalWORKs Families. Prior to 2005, if the state chose to pass through past‑due CalWORKs recoupment payments to former CalWORKs families, it would have had to use state funding to pay for—or backfill—the federal government’s loss of CalWORKs recoupment dollars (45 percent of the payment). However, in 2005, the federal government changed its policy and allowed states to pass through the full amount of past‑due recoupment payments to formerly assisted parents without providing a federal backfill. While states do not have to provide a federal backfill, they still would experience a loss in state (and county) revenue. We understand that currently Wisconsin is the only state that fully passes through past‑due recoupment payments to formerly assisted families.

Governor’s 2022‑23 Pass‑Through Proposal

Governor’s Budget Proposes to Fully Pass Through Past‑Due CalWORKs Recoupment Payments to Former CalWORKs Families. The Governor’s budget proposes to fully pass through all past‑due CalWORKs recoupment payments that otherwise would have gone to the government to former CalWORKs families instead effective January 2023 (or when the automation can be completed—whichever is later). The administration estimates that this policy change would result in $93.5 million going to some former CalWORKs families in 2022‑23 (increasing to $187 million in 2024‑25 and ongoing). As shown in Figure 2, this reflects the total amount of estimated payments that otherwise would have gone to pay off the state, counties’, and federal government’s share of past‑due CalWORKs recoupment payments. Since the state does not have to backfill the associated federal loss in CalWORKs recoupment payments, the state would only experience a $47.4 million half‑year decrease in General Fund revenue in 2022‑23 (increasing to $94.9 million annually in 2024‑25 and ongoing). Additionally, the Governor is proposing to backfill the county loss in CalWORKs recoupment (thereby holding counties harmless), resulting in a total General Fund impact of $52.3 million in 2022‑23 ($104.6 million in 2024‑25 and ongoing).

Figure 2

Estimated Annual Revenues From

CalWORKs Recoupment Payments

for Former CalWORKs Casesa

(In Millions)

|

Revenue Estimates |

|

|

Federal share |

$82 |

|

State General Fund share |

95 |

|

County share |

10 |

|

Total Revenue |

$187 |

|

a Reflects administration’s 2024‑25 cost estimate of Governor’s budget proposal, which is based on actual 2020‑21 past‑due CalWORKs recoupment collections in former CalWORKs cases. |

|

Pass‑Through Amount for Current CalWORKs Families Would Remain the Same Under Governor’s Budget Proposal. As a part of the 2020‑21 budget, the state increased the pass‑through amount for current CalWORKs families from $50 to $100 for a family with one child and $200 for a family with two or more children. This change took effect January 1, 2022. The Governor’s budget proposal would only impact former CalWORKs families, meaning that the pass‑through amount for current CalWORKs families would remain the same.

LAO Assessment

Governor’s Budget Mainly Benefits Low‑Income Former CalWORKs Parents With Adult Children. Under the Governor’s proposal, DCSS estimates that of the total number of about 640,000 former CalWORKs cases, nearly 69,000 would receive, on average, about $170 in any given month in past due payments. Based on our conversations with the administration, the average profile of the former CalWORKs case that would benefit from the policy change is a low‑income, 52‑year‑old parent who no longer has an active child support order. Specifically, of the nearly 69,000 former CalWORKs families that would benefit from the Governor’s budget proposal, the administration estimates that about 25 percent of them still have an active child support order, meaning their child is under 18 years old. The remaining 75 percent of these former CalWORKs cases no longer have an active child support order, likely because their child has reached adulthood.

Governor’s Cost Estimates May Change Based on Actual 2022‑23 Collection Levels. We understand that the costs associated with the Governor’s budget proposal ($52.3 million General Fund half‑year and $104.6 million General Fund annually) are based on actual 2020‑21 past‑due CalWORKs recoupment collections in former CalWORKs cases. This means that the costs of the Governor’s budget proposal may be lower (or higher) if collections in former CalWORKs cases decrease (or increase). For example, since 2011‑12, total CalWORKs recoupment collections have declined, on average, by 3 percent annually. To the extent annual collections continue to decline at a similar rate, the costs associated with the Governor’s budget proposal could decrease to roughly $45 million half‑year General Fund in 2022‑23 (roughly $95 million General Fund in 2024‑25).

Governor’s Pass‑Through Proposal Aligns With Federal Flexibilities… The current pass‑through policy for current CalWORKs families reflects the maximum amount of CalWORKs recoupment payments the federal government is willing to pass through to these families without requiring the state to backfill the federal loss of CalWORKs recoupment. Similar to the pass‑through policy for current CalWORKs families (the first $100 or $200), the Governor’s budget proposal would increase the pass‑through amount for former CalWORKs families to reflect the maximum amount of CalWORKs recoupment payment the federal government is willing to pass through to these families (100 percent of payments).

…But Does Not Identify a Clear Reason to Continue to Have Different Pass‑Through Policies for Current and Former CalWORKs Families. One stated goal of the administration’s proposal is to help low‑income families stabilize their financial position. This is similar to the broader child support program goal of increasing child support collections to children and families. This same rationale could be made for any policy that increases the pass‑through amount for all families—both current and former CalWORKs families. Moreover, while the majority of current and former CalWORKs families in the child support program tend to be low income, a full pass‑through policy generally would have a greater impact on income levels for current CalWORKs families, who tend to report even lower income on average than former CalWORKs families. Specifically, based on data from the child support program, in FFY 2018, roughly 75 percent of current CalWORKs families had reported annual incomes of less than $10,000 (relative to 57 percent of former CalWORKs families), while roughly 90 percent had reported income of less than $20,000 (relative to roughly 75 percent of former CalWORKs families). Moreover, a full pass‑through policy that is limited to former CalWORKs families would not maximize the child support program goal of increasing collections going to children and families relative to if the full pass‑through policy included current CalWORKs families. This is because current CalWORKs families have minor children, while the former CalWORKs cases that would benefit from the Governor’s budget proposal are more likely to have children that are over the age of 18.

Governor’s Budget Proposal Represents One Pass‑Through Policy Option. The Governor’s budget proposal reflects one way the state could pass through a higher amount of payments to low‑income families. Figure 3 compares the Governor’s budget proposal to other pass‑through policies that instead target current CalWORKs families. These policy options are not mutually exclusive, meaning the state could change the pass‑through amounts for both current and former CalWORKs families. (These options could not be implemented until 2024‑25 at the earliest due to information technology‑related automation changes.) Any changes to the pass‑through policy for current CalWORKs families also would need to consider whether any changes to how child support is treated for purposes of determining CalWORKs eligibility and any other social services programs would be required. We describe each policy option in more detail below.

- Pass‑Through Full CalWORKs Recoupment Payment to Current CalWORKs Families. As previously mentioned, as a result of a recent change in law, the first $100 (or $200) of a current support payment is passed through to current CalWORKs families with one child (or two or more children). The remaining amount of the current support payment is retained by the government to recoup costs associated with CalWORKs cash aid provided to families. The administration projects that the state will collect roughly $150 million in total CalWORKs recoupment in current CalWORKs cases in 2022‑23. The state could choose to fully pass through current support payments to current CalWORKs families instead of retaining a portion of these payments for government CalWORKs recoupment purposes. Under this policy option, the state would have to backfill the federal loss of CalWORKs recoupment dollars (45 percent of the payment) above current pass‑through levels. Additionally, this policy change would result in a decrease in General Fund and county revenue. Assuming a 2024‑25 implementation date, the costs associated with this policy option would depend on the number of current CalWORKs cases and associated collections in 2024‑25. Specifically, actual costs could be lower (or higher) if current CalWORKs cases and associated collections decrease (or increase) by 2024‑25. If caseload and collection trends remain flat relative to estimated 2022‑23 levels, the General Fund costs associated with this policy change would total roughly $150 million annually in 2024‑25. However, we estimate that CalWORKs caseload will increase and be higher in 2024‑25 relative to current caseload levels, meaning that costs associated with this policy option may be higher than $150 million General Fund.

- Pass‑Through Nonfederal Share of CalWORKs Recoupment Payments to Current CalWORKs Families. Alternatively, the Legislature could consider adopting a pass‑through policy that would only pass through the full nonfederal (state and county) share of CalWORKs recoupment to current CalWORKs families—allowing the federal government to continue receiving recoupment for the cost of CalWORKs cash aid. This means that the state would continue to collect the federal share of CalWORKs recoupment (45 percent of the payment) to avoid backfilling the federal loss in CalWORKs recoupment. Of the roughly $150 million in total CalWORKs recoupment in current CalWORKs cases the state is projected to collect in 2022‑23, roughly $80 million reflects the nonfederal share. If caseload and collection trends remain flat relative to estimated 2022‑23 levels, the General Fund costs associated with this policy change would then total roughly $80 million annually in 2024‑25. However, we estimate that CalWORKs caseload will increase and be higher in 2024‑25 relative to current caseload levels, meaning that costs associated with this policy option may be higher than $80 million General Fund.

Figure 3

Summary of Various Pass‑Through Policy Optionsa

|

Description |

Earliest Possible |

Estimated Annual |

|

Options for Former CalWORKs Families |

||

|

Pass through the full amount of past‑due CalWORKs recoupment payments to former CalWORKs families (as proposed under Governor’s budget). |

January 2023 |

$105 million |

|

Options for Current CalWORKs Families |

||

|

Pass through the full amount of CalWORKs recoupment payments to current CalWORKs families. |

Sometime in 2024‑25 |

$150 million |

|

Pass through the nonfederal amount of CalWORKs recoupment payments to current CalWORKs families. |

Sometime in 2024‑25 |

$80 million |

|

aPass‑through options for current and former CalWORKs families are not mutually exclusive, meaning the state could change the pass through policy for both former and current CalWORKs families. bAdministration estimates that changes to the pass‑through amount provided to current CalWORKs families could not take effect until sometime in 2024‑25 as a result of limited opportunities to make automation changes. cThese cost estimates generally reflect current payments collected in current and former CalWORKs cases. Actual costs would be higher (or lower) depending on whether caseload and collection trends increase (or decrease) by January 2023 (for former CalWORKs families) or 2024‑25 (for current CalWORKs families). Additionally, cost estimates do not include costs for automation changes or impacts to CalWORKs program. |

||

Legislature Could Consider Supplementing Governor’s Proposal With Other Pass‑Through Policy Change. Overall, the Legislature may want to select a pass‑through policy (or policies) that maximizes current program goals and broader goals the Legislature would like to achieve. For example, the Governor’s budget proposal reflects the pass‑through option that likely could be implemented sooner (January 2023) relative to pass‑through policies for current CalWORKs families (sometime in 2024‑25 at the earliest). Additionally, the Governor’s budget proposal would not require that the state backfill the federal share of loss in CalWORKs recoupment. However, implementing a pass‑through policy that only benefits former CalWORKs families would create a disparity in the amount of payment received by current CalWORKs families. Specifically, families whose child support payments were made while they participated in CalWORKs would only receive a portion of those funds. In contrast, families whose payments were not made while participating in CalWORKs would receive the full amount of those payments if they were made after the family left CalWORKs. If the Legislature wanted to ensure all low‑income families in the child support program receive the same treatment under its pass‑through policy, it could consider supplementing the Governor’s proposal with a full pass‑through policy for current CalWORKs families (once the necessary automation changes could be made). In that case, the Legislature could consider providing any necessary resources in 2022‑23 to begin planning activities to ensure that the automation changes needed to implement the pass‑through change for current CalWORKs families are implemented as soon as possible in 2024‑25. Additionally, the Legislature may want to consider how it would want to address any possible impacts the changes to the pass‑through amount may have on eligibility for CalWORKs and any other social services programs.

Provide Additional LCSA Administrative Funding

LAO Bottom Line: Withhold Future Funding Augmentations Until LCSA Funding Methodology Maximizes Program Efficiencies and Accurately Reflects Funding Needs. The Governor’s proposal to increase LCSA administrative funding continues to be based on a funding methodology that falls short in exploring ways to control costs through program efficiencies. Moreover, given recent and anticipated changes to the child support program, we cannot say with certainty that the funding methodology accurately estimates actual funding needs. We recommend the Legislature withhold action on providing any future funding augmentations until the administration revises the LCSA funding methodology to addresses identified shortcomings. We provide examples of possible improvements that could be made to the LCSA funding methodology, many of which reflect common funding strategies in other social services programs.

Background

2019‑20 LCSA Administrative Funding Methodology Structured to Increase General Fund Levels Over Three Years. As shown in Figure 4, in 2019‑20, the administration proposed to increase LCSA administrative funding by $19.1 million General Fund, ramping up to $57.2 million General Fund over three years, to increase staffing levels in LCSAs that did not have enough funding to reach target staffing levels (referred to as underfunded LCSAs). Additionally, under the funding methodology, overfunded LCSAs were allowed to maintain excess funds ($17.5 million General Fund in 2019‑20). (If the excess funds were redistributed to underfunded LCSAs, the 2019‑20 estimate of additional General Fund needed by underfunded LCSAs would have decreased from $57.2 million to $39.7 million.) As previously mentioned, the administration has updated its calculation of LCSA funding needs under the funding methodology every year to reflect most recent caseload levels and locally negotiated salary and benefit costs.

Figure 4

Estimate of Total General Fund Levels Under

Administration’s LCSA Funding Methodology

in 2019‑20

General Fund (In Millions)

|

Total Funding Levels… |

Total Funding Increase Under Funding Methodology |

|

|

...Prior to Funding Methodology Implementation |

…After Implementation of Funding Methodology |

|

|

$246.5 |

$303.7 |

$57.2 |

2019‑20 LCSA Funding Augmentation Was Eliminated but Ultimately Restored in Recent Budget Cycle. The 2019‑20 budget provided an additional $19.1 million General Fund for underfunded LCSAs, increasing total LCSA administrative funding levels from $246.5 million General Fund to $265.6 million General Fund. However, the 2019‑20 budget did not include statutory language that automatically ramped this up to $57.2 million in later years. As a part of the 2020‑21 budget, the $19.1 million General Fund augmentation provided in 2019‑20 was eliminated (in response to an anticipated budget problem). The $19.1 million General Fund reduction was implemented in a way where underfunded LCSAs experienced a relatively smaller reduction to funding levels than overfunded LCSAs. In the 2021‑22 budget, however, the state restored the $19.1 million General Fund ongoing augmentation and distributed the funds to underfunded LCSAs.

LCSAs Are Still Working Towards Fully Spending Prior Funding Augmentation. As of September 2021, statewide LCSA staffing levels that are used to determine funding needs under the administration’s funding methodology have decreased by 1.2 percent (from about 5,200 staff in June 2021 to 5,135 staff). In the case of underfunded LCSAs, only eight (or about one‑fourth of underfunded LCSAs) have experienced slight net increases in staffing levels since June 2021 (on average, three new hires since June 2021). In a recent report to the Legislature, DCSS noted that the decline in staffing levels partially is due to higher staff turnover (including resignations and retirements), fewer responses to job postings, and fewer candidates accepting job offers. If this trend continues through June 2022, the majority of the $19.1 million General Fund provided in 2021‑22 likely will go unspent.

Governor’s 2022‑23 Administrative Funding Proposal

Governor’s Budget Proposes to Increase LCSA Funding Levels by $20.1 Million to Assist Underfunded LCSAs to Reach Administration’s Staffing Goals. The Governor’s budget proposes to increase LCSA administrative funding by $20.1 million General Fund in 2022‑23. This funding would be distributed to 31 identified underfunded LCSAs. Similar to the 2019‑20 estimate of funding needs, this incremental increase reflects only a portion of the amount needed to reach $300 million total General Fund ($871.4 million total funds) that the LCSA funding methodology estimates is needed to (1) increase staffing levels in underfunded LCSAs to reach the administration’s staff goals (about 185 cases per staff), and (2) allow overfunded LCSAs to keep existing excess funds. (We understand that the administration may request to ramp up this ongoing General Fund increase by the remaining $14.2 million—reaching $34.3 million General Fund—to reach $300 million total General Fund in a future year depending on the availability of funding.)

LAO Assessment and Recommendations

Governor’s Budget Proposal Reflects Updated Calculation of LCSA Funding Needs Under Funding Methodology. As previously mentioned, the costs associated with the administration’s LCSA funding methodology consist of (1) providing additional funding to underfunded LCSAs to reach target staffing levels, and (2) allowing overfunded LCSAs to keep existing excess funds (rather than redistributing these funds to meet funding needs in underfunded LCSAs). As shown in Figure 5, the administration’s current estimate of additional General Fund needed above 2018‑19 funding levels ($53.5 million General Fund) is lower than the 2019‑20 estimate ($57.2 million General Fund). This net decrease in additional General Fund needed under the LCSA funding methodology is due to the decrease in excess funds allowed to be kept by overfunded LCSAs ($13.8 million General Fund decrease) fully offsetting the increase in the amount of additional funding needed by underfunded LCSAs ($10 million General Fund increase). We describe these two components in more detail below.

- Number of Underfunded LCSAs and Total LCSA Funding Needs Increased Relative to 2019‑20 Estimates. Since 2019‑20, more LCSAs have been identified as underfunded under the funding methodology (21 LCSAs to 31 LCSAs). As a result, the amount of additional General Fund needed by underfunded LCSAs has increased by $10.1 million General Fund—from $39.7 million General Fund to $49.8 million General Fund. The increase in the number of underfunded LCSAs and overall funding needs primarily is due to growth in LCSA salary and benefit levels between 2019‑20 and 2021‑22 (17 percent) making it more costly for these LCSAs to reach administration’s staffing goals. (A portion of these costs were offset by a 10 percent decrease in statewide child support caseload levels since 2019‑20.)

- Recent Reductions to Overfunded LCSA Budgets Reduced Additional General Fund Needed Under Administration’s LCSA Funding Methodology. The administration could redistribute existing funds from overfunded LCSAs to underfunded LCSAs to help underfunded LCSAs reach target staffing levels. In 2019‑20, the administration proposed to not redistribute excess funds in overfunded LCSAs, which increased the costs associated with the LCSA funding methodology by $17.5 million General Fund. In 2020‑21, in response to an anticipated statewide budget shortfall, total LCSA funding levels were reduced by $19.1 million General Fund. This funding decrease was implemented in a way where overfunded LCSAs experienced a greater reduction to funding levels than underfunded LCSAs. When the $19.1 million General Fund was restored in 2021‑22, funds were only distributed to underfunded LCSAs, meaning excess funds in overfunded LCSAs were not restored. This essentially had the effect of redistributing funds from overfunded LCSAs to underfunded LCSAs, which reduced the overall costs of the administration’s funding methodology. As previously mentioned, the Governor’s budget proposes to allow overfunded LCSAs keep $3.7 million General Fund in remaining excess funding. If these existing excess funds were redistributed to underfunded LCSAs, the cost of the Governor’s budget proposal would decrease from $20.1 million General Fund to $16.4 million General Fund.

Figure 5

Comparison of Past and Current Estimates of Needed Funding

Increase Under Administration’s LCSA Funding Methodology

General Fund (In Millions)

|

2019‑20 Estimate |

Governor’s 2022‑23 Budget |

Difference |

|

|

Additional funding needed by underfunded LCSAs |

$39.7 |

$49.8 |

$10.1 |

|

Existing excess funds kept by overfunded LCSAs |

17.5 |

3.7 |

‑13.8 |

|

Total Funding Increasesa |

$57.2 |

$53.5 |

‑$3.7 |

|

a Total funding increase calculated under the LCSA funding methodology would be lower if the existing excess funds in overfunded LCSAs were redistributed to underfunded LCSAs. |

|||

|

LCSA = local child support agency. |

|||

Governor’s Budget Proposal Does Not Maximize Program Efficiencies. Over the years, the Legislature has required the administration to consult with stakeholders and report back on possible program efficiencies that could improve customer service, collectability, and overall cost‑effectiveness. The LCSA funding methodology could be structured in a way to incentivize the adoption of previously identified program efficiencies as a way to alleviate cost pressures and control overall program costs. For example, an LCSA can either operate its own call center or send its calls to a regional call center operated by another LCSA (which we understand generally provide a similar level of service to families). In developing the original 2019‑20 LCSA funding methodology, the administration considered providing LCSAs only with enough funding to operate the most cost‑effective call center based on a standard call per employee ratio and fixed cost per call. To the extent that an LCSA decided to operate a less cost‑effective call center, it would have to absorb the costs above its call center allocation. However, the administration ultimately decided not to fully build in this incentive structure. Overall, the Governor’s budget does not propose any changes to the LCSA funding methodology that would further incentivize LCSAs to adopt the most cost‑effective call center or other program efficiencies.

Concern That Governor’s Budget Proposal Does Not Accurately Reflect Current and Future LCSA Administrative Funding Needs. As previously mentioned, the administration continues to use the funding methodology developed in 2019‑20 to estimate current and future LCSA administrative funding needs based on 2018 operation levels. This essentially means that the Governor’s budget proposal assumes that LCSA operations and associated staffing needs will continue to reflect 2018 levels. However, the COVID‑19 pandemic has required LCSAs to completely restructure how the child support program is administered since 2018, relying more on electronic and virtual tools to serve families. Some of these program changes reflected previously identified program efficiencies, such as electronic signature and filing of program forms.

Given the rise of Omicron as the prevailing COVID‑19 variant, LCSAs likely will continue to operate the program differently in the near term relative to pre‑COVID‑19 levels. Moreover, at this time, whether some of the temporary program changes adopted during the pandemic would be continued on a permanent basis, and if so, how the changes would impact ongoing staffing needs is unclear. For example, during the pandemic, many LCSAs transitioned from requiring wet signatures on program forms to accepting electronic signatures. We understand that this generally had the effect of reducing document processing time, improving hearing time lines, and ultimately freeing up staff time to focus on other program priorities. As a part of the 2021‑22 budget, the state permanently expanded electronic signature capacity to all LCSAs, which likely will reduce ongoing clerical workload relative to 2018 operation levels.

Additionally, when the public health concerns abate, LCSAs likely will not return to administering the program exactly like they did in 2018 due to the adoption of federally required program changes. Specifically, the state is required to adopt new program rules by September 2024 in order to comply with the federal Flexibility, Efficiency, and Modernization in Child Support Enforcement Final Rule (referred to as the FEM final rule). As summarized in Figure 6, the FEM final rule generally places a greater emphasis on setting orders based on actual earnings in order to collect more reliable child support payments. As a part of the Governor’s budget, the administration proposes language to implement the FEM final rule (which we discuss in more detail in a later section). These proposed changes likely would require LCSA staff to perform new tasks or perform existing tasks differently relative to 2018 program operations. At this time, the LCSA administrative funding methodology does not include any costs associated with the possible program changes related to the FEM final rule. As a result, even if the existing funding methodology was deemed appropriate in 2019‑20, there is no certainty that it accurately measures current and future LCSA administrative funding needs.

Figure 6

2016 Federal Guidance Prioritizes Consistency and Ability to Pay

Major Features of the Flexibility, Efficiency and Modernization in

Child Support Enforcement Programs Final Rule, December 2016

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Overview of Federal Final Rule, Flexibility, Efficiency, and Modernization in Child Support Enforcement Programs. |

Recommend Revising LCSA Administrative Funding Methodology Before Providing Any Future Funding Augmentations. We recommend the Legislature withhold action on any future LCSA funding increases until the administration revises its funding methodology to maximize program efficiencies and accurately reflect actual funding needs associated with the program in light of the pandemic and the FEM final rule. In general, revising the LCSA funding methodology prior to providing funding increases makes sense because it is more difficult to make changes to funding levels after funds have been provided and spent. Additionally, LCSAs may not immediately need additional funding in 2022‑23 since LCSAs have not yet used most of the funding provided in 2021‑22 to increase staffing levels.

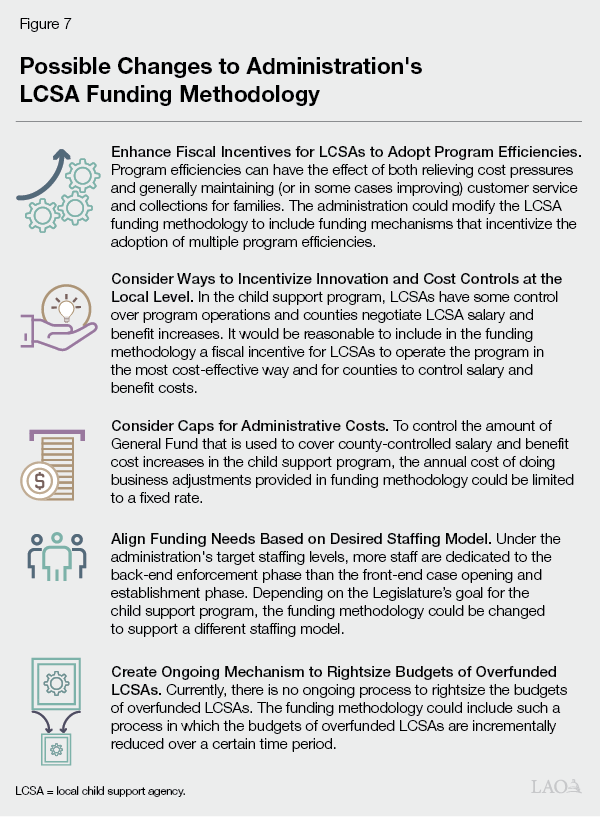

Figure 7 summarizes changes that could be made to the LCSA funding methodology to address the identified shortcomings. Many of these changes reflect common funding strategies used in other social services programs. We describe each change in more detail below.

- Enhance Fiscal Incentives for LCSAs to Adopt Program Efficiencies. The LCSAs have some level of discretion over executing program rules in the most cost‑effective manner. Over the years, the Legislature has required the administration to consult with stakeholders and report back on possible child support program efficiencies that could improve customer service, collectability, and overall cost‑effectiveness. Program efficiencies can have the effect of both relieving cost pressures and generally maintaining (or in some cases improving) customer service and collections for families. For example, some LCSAs currently send complex cases (such as international cases) to specialized units operated by other LCSAs. By sending cases to these specialized units, LCSAs free up staff time and resources for other program priorities. Additionally, specialized units are able to execute tasks associated with complex child support cases more quickly and ultimately get payments to families sooner. Overall, the administration could modify the LCSA funding methodology to include funding mechanisms that incentivize the adoption of multiple program efficiencies (similar to how the administration initially considered incentivizing LCSAs to select the most cost‑effective call center model based on both a standard call per employee ratio and fixed cost per call).

- Consider Ways to Incentivize Innovation and Cost Controls at The Local Level. In the child support program, LCSAs have some control over program operations and counties establish LCSA salary and benefit levels (the primary cost driver in the program today), yet they have very little fiscal incentive to reduce or control costs. For these reasons, including a fiscal incentive for LCSAs to operate the program in the most cost‑effective way and control the state’s share of salary and benefit costs would be reasonable. A possible fiscal incentive could be structured in many ways, including the establishment of a county share of cost, limiting the use of additional General Fund to support the implementation of cost‑effective program changes, or requiring a county match for LCSAs to draw down future General Fund increases. Overall, the structure of the fiscal incentive would need to adhere to state mandate laws.

- Consider Caps for Administrative Costs. Under the current LCSA funding methodology, the amount of General Fund is adjusted to reflect the full growth in LCSA salary and benefit costs, or the costs of doing business. Salary and benefit levels for LCSAs and other social services programs are negotiated and established by each county. These upward cost of doing business adjustments for LCSAs typically outweigh the possible General Fund savings resulting from declining caseload levels. To control the amount of General Fund that is used to cover county‑controlled salary and benefit cost increases in the child support program, the LCSA funding methodology could instead limit the cost of doing business adjustment to a fixed rate.

- Align Funding Needs Based on Desired Staffing Model. As previously mentioned, the existing LCSA funding methodology is based on a 2018 calculation of total staffing needs. Based on this calculation, the administration estimated that about half of program staff would need to consist of management and support staff (such as clerical, training, and financial employees). Moreover, about 40 percent of program staff would need to provide back‑end enforcement services, while only 7 percent of staff would need to provide front‑end case opening and establishment services. This target staffing model does not fully align with the FEM final rule, which emphasizes the need to provide more front‑end services as a way to better engage both parents, establish orders that reflect ability to pay, and increase overall collections to families. Depending on the Legislature’s goal for the child support program, the LCSA funding methodology could be changed to support a different staffing model that better aligns with those goals.

- Create Ongoing Mechanism to Rightsize Budgets of Overfunded LCSAs. As previously mentioned, overfunded LCSAs were significantly rightsized as a result of a one‑time 2020‑21 funding reduction to LCSA funding levels. The administration estimates that 16 LCSAs continue to be overfunded by $3.7 million total General Fund ($10.9 million total funds). The LCSA funding methodology does not include an ongoing process in which overfunded LCSA budgets are rightsized and the excess funding is redistributed to underfunded LCSAs. This essentially maintains a funding disparity in which some LCSAs receive excess funds that can be used for program costs and activities beyond what is deemed necessary under the administration’s LCSA funding methodology. The administration expects the budgets of overfunded LCSAs to naturally right‑size over time. This would occur by LCSA salary and benefit costs continuing to increase to a point where overfunded LCSAs can no longer afford to keep staffing levels above target staffing levels. At that point, these LCSAs would be deemed underfunded and receive additional General Fund for future salary and benefit increases. Overall, a revised LCSA funding methodology could include an ongoing process in which the budgets of current and future overfunded LCSAs are incrementally reduced over a certain time period. Additionally, given that many LCSAs may not fully spend their funding allocations due to declining staffing levels, it may be possible to rightsize some or all overfunded LCSAs in 2022‑23 without reducing their current staffing levels.

Statutory Changes to Comply with Recent Federal Reforms

LAO Bottom Line: Initial Questions and Comments to Assist Legislature’s Review of FEM Final Rule Compliance TBL. The administration proposes trailer bill language (TBL) to bring the state into compliance with the FEM final rule. For example, the FEM final rule requires the state to expand the number of variables it considers when establishing a child support order to better reflect a parent’s ability to pay, including income history, health issues, and educational attainment. In general, the state must comply with the FEM final rule by September 2024. We are still in the process of completing our review of the proposed TBL. Below, we provide initial questions and comments to assist the Legislature in assessing the language. We will provide any necessary updates to our questions and comments once we complete our review of the proposal.

- Consider Establishing Important Implementation Details in Statute. We understand that in 2019‑20, similar changes needed to comply with the FEM Final Rule were being considered through the policy process (AB 3334 [Weber]). At the time, the policy bill defined many components of the FEM final rule at a high level and left many of the implementation details up to the administration and possibly individual LCSAs and courts. One thing we are considering in our review of the TBL is if the Legislature may want to consider adopting more detailed language and uniform processes in statute to ensure similarly situated parents and families are treated equitably across LCSAs and courts.

- Request Summary of Stakeholder Feedback. DCSS received input from stakeholders (including LCSAs and courts) on the proposed program changes. The Legislature may want to request a summary of stakeholder feedback and whether the proposed TBL addresses any significant concerns.

- Request Information on How Proposed Changes Will Change Current Practice for Each Program Actor. Both LCSAs and courts play important roles in establishing and enforcing child support orders. The Legislature may want to request additional information on how the proposed changes will impact the roles and responsibilities of all entities involved in administering the child support program, including courts.

- Consider Whether Proposed Changes Should Be Considered Through Policy Process. As previously mentioned, similar changes to comply with the FEM final rule were being considered through the policy process in 2019‑20. According to the administration, if the state is not in compliance by September 2024 it may be at risk of incurring federal fiscal penalties (possibly $700 million in reduced federal matching funds if the state’s child support plan is denied by the federal government due to FEM final rule noncompliance). Overall, the Legislature may want to consider to what extent the proposed changes are better suited to be considered through the policy process relative to the budget process.