LAO Contact

February 22, 2022

The 2022-23 Budget

Clean Energy Package

- Background

- Proposal

- Overarching Issues for Legislative Consideration

- Assessment of and Recommendations on Specific Programs

- Conclusion

Summary

Governor Proposes $2 Billion Clean Energy Package. The Governor proposes $2 billion over two years—almost all General Fund—for a package of proposals intended to help meet the state’s long‑term greenhouse gas (GHG) goals. Funding would mostly go to new programs, such as equitable building decarbonization programs, long duration storage projects, an Oroville pump storage project, industrial decarbonization, and green hydrogen projects.

Package Generally Targets Reasonable Set of Activities to Promote Deep Decarbonization. A significant portion of the funding would support areas where substantial technological progress is needed to lower the cost of achieving long‑term GHG goals. In addition, the equitable building decarbonization programs target one of the largest sources of statewide GHG emissions.

Allocating State General Fund, Rather Than Ratepayer Funds, Has Merit. We think there is a strong rationale for using one‑time General Fund for these types of programs. By using General Fund instead of ratepayer funds, the Legislature can help limit future increases in electricity rates, which discourage electrification and have regressive effects.

Balancing Long‑Term Benefits Against Near‑Term Priorities. Much of the proposed funding is focused on activities needed to meet long‑term, deep decarbonization goals. The Legislature will want to balance the potential long‑term benefits of the programs in the Governor’s package with other near‑ and medium‑term priorities.

Significant Federal Funding Available for Similar Activities. The federal Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act includes funding for a wide range of energy‑related activities. The Legislature might want to direct the administration to develop a strategy for using state funds in a way that best complements federal funding.

Expanding Scope of Certain Programs Could Improve Outcomes. The Governor’s proposal targets certain types of technologies and sectors, while excluding others. The Legislature could consider making the funding available to a broader range of technologies and businesses that might have the potential to help the state meet its long‑term climate goals.

Recommendations on Specific Proposals. We recommend the Legislature (1) direct the administration to provide additional detail on equitable building decarbonization programs (such as what role will these programs will play relative to other policy strategies and why is the California Energy Commission the most appropriate agency to administer the direct install program), (2) direct the administration to provide additional justification for the Oroville Project given the lack adequate detail about the cost‑effectiveness of this project relative to other options, and (3) reject proposed funding for the Department of Water Resources to support energy reliability due to lack of justification.

Background

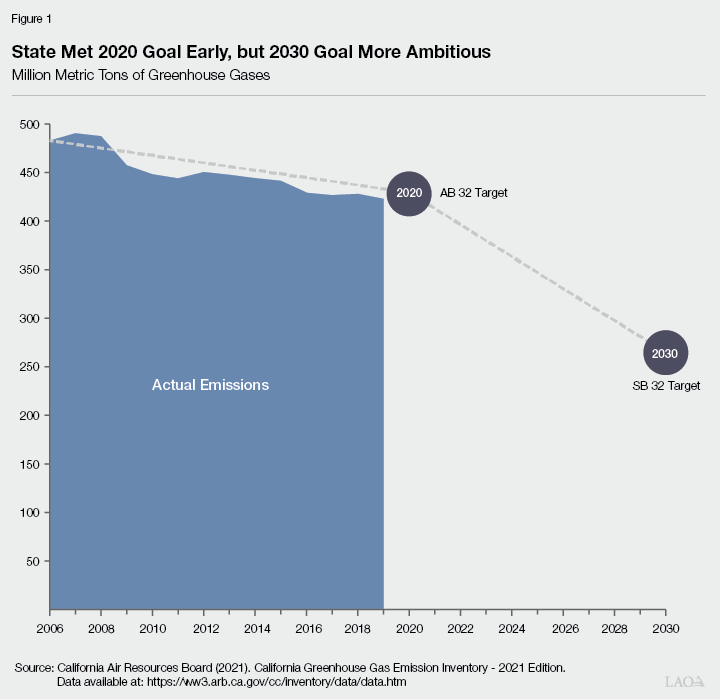

Legislature and Governor Have Ambitious Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Goals. Chapter 488 of 2006 (AB 32, Núñez/Pavley) established the goal of limiting GHG emissions statewide to 1990 levels by 2020. In 2016, Chapter 249 (SB 32, Pavley) extended the limit to 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030. As shown in Figure 1, emissions have decreased since AB 32 was enacted and were below the 2020 target in 2019. However, the rate of reductions needed to reach the SB 32 target are much greater.

The administration has also established long‑term GHG goals. On September 10, 2018 Governor Brown issued Executive Order B‑55‑18 which established a statewide goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2045—meaning annual GHG emissions are equal to or less than carbon dioxide sequestered or stored. Reducing net GHG emissions to near (or below) zero is also known as deep decarbonization. Notably, the Legislature has not adopted long‑term statewide deep decarbonization goals in law. However, as discussed below, the Legislature has established specific long‑term decarbonization goals in certain sectors, such as the electricity sector.

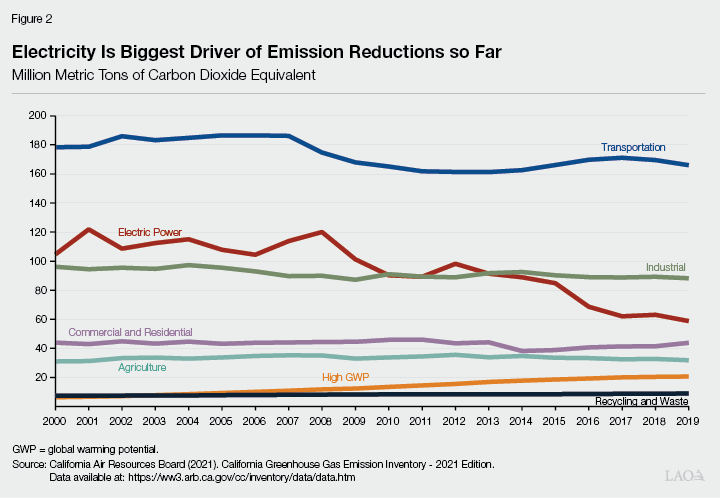

Emission Reductions Have Been Driven by Electricity Sector. Over the last decade, the electricity sector has been the primary driver of statewide GHG emission reductions, as shown in Figure 2. Reductions from the electricity sector mostly reflect a changing mix of resources used to generate electricity—primarily large increases in renewables (solar and wind) along with a decline in coal generation. A wide variety of factors have contributed to this shift, including technological advancements, changing economic conditions, federal policies, and state policies. (For more detail, see our report, Assessing California’s Climate Policies—Electricity Generation.) Notably, emissions from other sectors—including residential and commercial buildings, industrial facilities, and high global warming potential products (such as refrigerants)—have remained relatively steady or increased over the last several years.

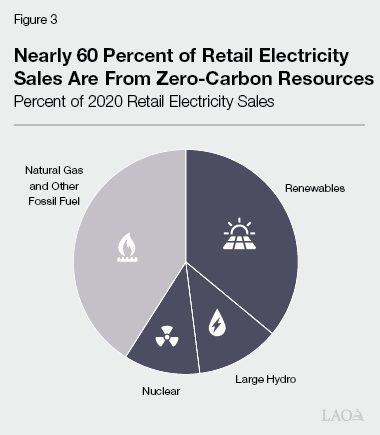

State Law Establishes Policy of 100 Percent Zero‑Carbon Electricity by 2045. Chapter 312 of 2018 (SB 100, de León) established a state policy of providing 100 percent of retail electricity with zero‑carbon resources by 2045. As shown in Figure 3, 59 percent of retail electricity sales came from zero‑carbon resources in 2020, including 36 percent from resources that qualify as renewable under the state’s Renewable Portfolio Standards, such as onshore wind and solar photovoltaic.

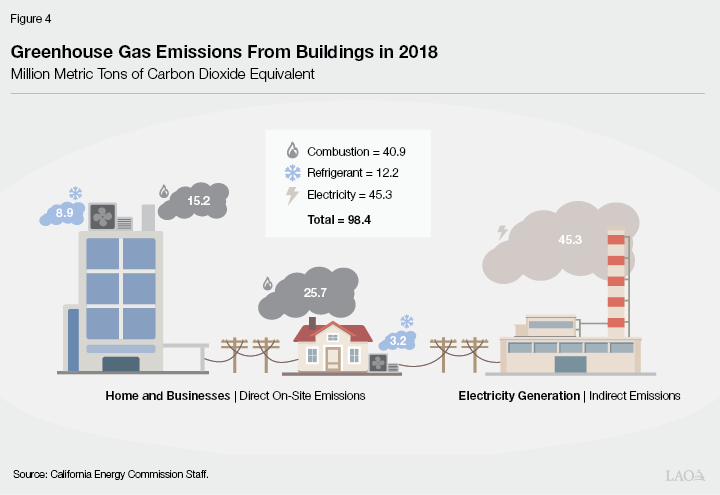

Several Different Strategies Aim to Reduce Emissions From Buildings. As shown in Figure 4, California commercial and residential buildings generated nearly 100 million tons of emissions in 2018—or nearly one‑quarter of annual statewide emissions. The three main categories of GHG emissions from buildings are:

- Combustion. Emissions from burning fossil fuels on site—primarily natural gas—largely related to space heating and water heating.

- Refrigerants. Leakage of certain types of refrigerants, such as hydrofluorocarbons, found in supermarket refrigeration and air conditioning units.

- Electricity Generation. Indirect emissions from the electricity system that generates the electricity for buildings.

Historically, state efforts to reduce emissions from buildings has focused on improving the energy efficiency of buildings and appliances. For example, the California Energy Commission (CEC) develops energy efficiency building codes and standards for new buildings. Additionally, utilities operate programs using ratepayer funds—totaling at least several hundred million dollars annually—that aim to promote energy efficient appliances and buildings. The California Department of Community Services and Development (CSD) administers a wide variety of other programs that provide energy efficiency upgrades for low‑income households, including the state Low‑Income Weatherization Program and the federal Weatherization Assistance Program. Finally, we note that the state supports energy efficiency activities at state buildings, schools, and universities.

Recent State Efforts Have Focused on Building Electrification. In recent years, state efforts have increasingly focused on electrification as a key strategy for reducing emissions from buildings. This strategy aims to promote the use of electric appliances—such as heat pumps—instead of natural gas furnaces and water heaters. For example, Chapter 378 of 2018 (SB 1477, Stern) authorized the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) to develop the Building Initiative for Low‑Emissions Development (BUILD) Program to encourage the installation of electric appliances in new, low‑income residential housing in investor‑owned utility (IOU) territories. CPUC designated CEC as the program administrator. Senate Bill 1477 directed CPUC to support BUILD with $80 million from revenue collected from cap‑and‑trade allowances that are given to IOUs and then subsequently sold at auctions. (We describe the state’s overall cap‑and‑trade program in more detail later in this section.) In addition, a variety of other program, planning, and regulatory efforts have begun to focus on electrification as a key strategy for long‑term building decarbonization.

2021‑22 Budget Provided $172 Million for Energy Activities. As described in our post, The 2021‑22 California Spending Plan: Natural Resources and Environmental Protection, the 2021‑22 budget included $172 million for various energy‑related activities, including programs intended to promote building electrification, planning and permitting renewable energy projects, and activities intended to promote electric reliability. This included $75 million General Fund to CEC to expand the BUILD program to new market rate residential buildings in all areas of the state, including publicly owned utility territories.

Cap‑and‑Trade Is Main State Program for Industrial GHG Emissions. The state administers relatively few GHG emissions reduction programs for industrial sources. The main emission reduction program for industrial sources is the cap‑and‑trade program, which covers about 75 percent of statewide GHG emissions, including transportation, natural gas, electricity production, and industrial sources. Under this program, a limited number of permits to emit GHGs are issued and “covered entities” can buy and sell allowances. The program relies on market incentives—reflected through permit prices—and flexibility to encourage the lowest‑cost emission reduction activities.

Proposal

Governor Proposes $2 Billion Clean Energy Package. The Governor proposes $2 billion over two years—almost all General Fund—for a package of programs related to clean energy, building decarbonization, and emission reductions from industrial sources. Figure 5 summarizes the key pieces of the Governor’s proposed package. Most of the funding would go to new programs and activities. Some of the new programs—specifically long‑duration storage, Oroville pump storage, industrial decarbonization, and green hydrogen—were proposed by the Governor as part of last year’s May Revision for 2021‑22, but ultimately were not adopted as part of the final budget package. In the rest of this section, we describe the major new programs proposed.

Figure 5

Governor’s Proposed Clean Energy Package

General Fund (In Millions)

|

Program |

Department |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

Total |

|

Equitable building decarbonization |

CEC |

$323 |

$600 |

$922 |

|

Incentives for long duration storage projects |

CEC |

140 |

240 |

380 |

|

Oroville pump storage project |

DWR |

100 |

140 |

240 |

|

Industrial decarbonization |

CEC |

110 |

100 |

210 |

|

Green hydrogen projects |

CEC |

100 |

— |

100 |

|

Food Production Investment Program |

CEC |

85 |

— |

85 |

|

Offshore wind infrastructure |

CEC |

45 |

— |

45 |

|

Incentives for low GWP refrigerants |

CARB |

20 |

20 |

40 |

|

Energy modeling |

CEC |

7 |

— |

7 |

|

AB 525 implementation |

Various |

4a |

— |

4 |

|

Staffing to support energy reliability |

DWR |

3 |

— |

3 |

|

Distributed energy staffing |

CPUC |

1b |

1b |

3 |

|

Totals |

$938 |

$1,101 |

$2,039 |

|

|

a Includes $1.5 million from Energy Resources Program Account. |

||||

|

b From Public Utilities Commission Utilities Reimbursement Account. |

||||

|

CEC = California Energy Commission; DWR = Department of Water Resources; GWP = global warming potential; CARB = California Air Resources Board; AB 525 = Chapter 231 of 2021 (AB 525, Chiu); and CPUC = California Public Utilities Commission. |

||||

Equitable Building Decarbonization. The Governor’s budget provides a total of $922.4 million General Fund over two years ($323 million in 2022‑23 and $600 million in 2023‑24) to CEC for two new residential building decarbonization programs. These two programs include (1) $622.4 million for a program to directly install energy efficient and electric appliances in low‑ and moderate‑income households and (2) $300 million for a statewide rebate program for electric appliances that replace natural gas appliances.

Under the direct install program, contractors would undertake a variety of energy efficiency and building electrification changes (such as heat pumps and electrical panel upgrades) at no cost for eligible households. Eligible households would include households in disadvantaged communities (as measured in CalEnviroScreen), at or below 80 percent of statewide median income, or with income limits of moderate or below as identified by the California Housing and Community Development. CEC estimates that the program could reach 13,000 to 274,000 existing buildings at an estimated cost ranging from $2,000 to $40,000 per building. The statewide rebate program would provide incentives to purchase electric appliances, such as heat pump space and water heaters. Based on estimated costs of $1,000 to $8,000 per building, about 40,000 to 313,000 buildings would receive rebates under this program.

Long‑Duration Storage Projects. The proposed budget includes a total of $380 million General Fund ($140 million in 2022‑23 and $240 million in 2023‑24) for demonstrations and early stage deployment of long‑duration storage technologies—defined as technologies that can store energy for eight hours or more—that are on the verge of commercialization. According to the administration, the goal of the program is to help support the advancement of promising technologies from the demonstration phases to commercial deployment in the next five to ten years. Examples of technologies that might receive funding include flow batteries (batteries that use a different chemical process than traditional batteries), thermal storage, and compressed air technologies. (Pumped hydroelectric storage and lithium‑ion batteries would not be eligible technologies because they are not considered emerging technologies.)

The proposed program would be implemented in two phases. The first phase would include 12 to 16 demonstration projects ranging from three megawatts (MW) to five MW of capacity. The second phase would include fewer projects—roughly seven to ten—but most projects would range from five MW to ten MW. Some projects will also focus on much longer durations in the range of 20 to 100 hours. For context, a recent analysis from the state’s energy agencies found that there is a need for a minimum of about 1,000 MW of long‑duration storage by 2030 and 4,000 MW by 2045 to meet the state’s SB 100 goals of 100 percent zero‑carbon electricity.

Oroville Pump Storage Project. The Governor proposes a total of $240 million General Fund ($100 million in 2022‑23 and $140 million in 2023‑24) to modify the Oroville Dam complex so it can use its existing pump back operations to provide long‑duration energy storage without adverse impacts on spawning salmon in the Feather River. Funding would support the planning, design, permitting, and construction of the modifications necessary for the dam to use its existing 480 MW pumping capacity. The proposed funding would also support the construction of a flow control facility with a potential for an additional 20 MW hydroelectric generation.

Industrial Decarbonization. The Governor proposes a total of $210 million General Fund ($110 million in 2022‑23 and $100 million in 2023‑24) to deploy advanced technologies or develop novel strategies to reduce emissions at industrial facilities. According to the administration, eligible projects could include electrification of heating processes that now use natural gas, energy efficiency projects, and deploying carbon capture for use in products (such as concrete). Carbon capture projects with geologic storage and petroleum and gas production facilities would be ineligible.

Green Hydrogen Projects. The proposed budget includes $100 million General Fund in 2022‑23 to advance green hydrogen technology and explore different end uses. Green hydrogen is produced by splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen using renewable electricity. The administration estimates that the funding would support 10 to 15 commercial demonstration projects. About two‑thirds of the funding would focus on lowering the cost of electrolyzers used to produce green hydrogen. Other eligible projects include those that demonstrate the use of green hydrogen for industrial activities, power plants, and energy storage.

Overarching Issues for Legislative Consideration

In this section, we identify overarching comments for the Legislature to consider as it evaluates the Governor’s overall clean energy package.

Package Generally Targets a Reasonable Set of Activities to Promote Deep Decarbonization. In our view, the Governor’s proposed package reflects a reasonable set of activities to help the state achieve deep decarbonization. First, funding would support key areas where substantial technological progress could help lower the cost of achieving long‑term GHG goals. This includes technologies that can provide zero‑carbon electricity at times when renewable resources are not sufficient to meet electricity demand (such as long‑duration storage and green hydrogen) and technologies that can help reduce emissions from industrial activities (such as green hydrogen and carbon capture and storage). In general, we think there is a reasonable policy argument for government funding to promote the development of newer technologies because the private sector will likely underinvest in these activities. One‑time state funding to support demonstration projects to explore different technology options as proposed by the Governor could help advance these technologies, which in turn could help the state achieve some of its long‑term GHG goals at lower cost. In addition, since these technologies could also be used in jurisdictions outside of California, any advancements and cost reductions could have broader GHG benefits if these low‑carbon technologies get adopted in other jurisdictions.

The other largest pieces of funding—the equitable building decarbonization programs—target one of the largest sources of statewide GHG emissions. Furthermore, these programs would focus on existing buildings, which represents the vast majority of building‑related emissions and pose some of the most significant challenges to building decarbonization. For example, the long lifespan and slow turnover of major appliances in buildings means a transition to newer technologies in existing buildings can take decades. As a result, some near‑term actions could be important for meeting long‑term GHG goals.

Allocating State General Fund, Rather Than Ratepayer Funds, Has Merit. Many of state’s clean energy programs historically have been paid for by IOU ratepayers through higher electricity rates, even though some of the primary goals of these programs (such as GHG reductions) accrue to the broader public. We think there is a strong rationale for using General Fund for programs that aim to provide broad societal benefits. Additionally, the costs for clean energy programs are one factor that contributes to California’s relatively high retail electricity rates. (There are many other factors that impact electricity rates, which we do not discuss in this brief.) Electricity rates in California are more than twice as much as the estimated marginal social costs of providing electricity in California, even after accounting for environmental damages. These higher rates have a variety of adverse effects, including:

- High Electricity Rates Discourage Electrification. As discussed above, one strategy for deep decarbonization is electrification, including switching from natural gas appliances to electric appliances. Household and business decisions about appliance purchases depend, in part, on how much they would have to pay for electricity to operate the electric appliances. As a result, high electricity rates can discourage adoption of electric appliances.

- Electricity Rates Are a Regressive Approach to Raising Revenue. On average, lower‑income households tend to spend a greater share of their income on electricity than higher‑income households. As a result, collecting revenue through electricity rates is a relatively regressive approach to funding clean energy programs.

Balancing Long‑Term Benefits Against Near‑Term Priorities. Much of the proposed funding is focused on activities intended to meet long‑term, deep decarbonization goals. Although the proposed programs could have merit in the long run, some of these newer technologies and projects might take at least five to ten years to be commercially available, and even longer to become cost‑competitive. Some ultimately may not ever achieve commercial viability. As a result, the GHG reduction benefits are likely to be relatively modest over the next several years. The Legislature will want to balance the potential long‑term benefits of the programs in the Governor’s package with other near‑ and medium‑term priorities. For example, some alternative spending options include:

- Programs Aimed at Meeting 2030 GHG Goals. The state’s 2030 GHG goals will be difficult to meet. The Legislature could redirect some of the proposed funding to other programs that likely do more to help meet the state’s 2030 goals, such as methane reduction programs. In determining whether to prioritize General Fund resources for these such programs, the Legislature will want to consider the availability of other fund sources such as the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund.

- Other Energy‑Related Programs. The Legislature could prioritize funding for other energy‑related issues, such as grid resilience and reliability.

- Other Statewide Priorities. There might be other near‑term statewide issues outside of the energy and climate policy area that the Legislature considers a higher priority use of General Fund.

Significant Federal Funding Available for Similar Activities. As shown in Figure 6, the federal Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) that was enacted in November 2021 includes funding for a wide range of energy‑related activities. Notably, there is a significant amount of funding available for clean hydrogen hubs, carbon capture demonstration projects, industrial emissions demonstration projects, long‑duration storage demonstrations, and energy efficiency activities in low‑income households.

Figure 6

Select Federal IIJA Funding for Energy‑Related Activities

(In Millions)

|

Program |

Description |

2022‑2026 Funding |

Eligible Entities |

Estimated Application Date |

|

Clean Energy Demonstrations |

||||

|

Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs |

Development of at least four regional clean hydrogen hubs. |

$8,000 |

Private, state/local, NGO |

Summer 2022 |

|

Regional clean direct air capture hubs |

Development of four regional direct air capture hubs. |

3,500 |

Industry |

2nd quarter 2022 |

|

Carbon capture demonstration projects |

Development of six facilities to demonstrate carbon capture technologies. |

2,537 |

Private, state/local, NGO |

TBD |

|

Carbon storage validation and testing |

Research, development, and demonstration for carbon storage. |

2,500 |

Industry |

2nd quarter 2022 |

|

Clean Hydrogen Electrolysis Program |

Research, demonstration, and deployment program for technologies that produce clean hydrogen using electrolyzers. |

1,000 |

Industry |

2nd quarter 2022 |

|

Carbon capture large‑scale pilot projects |

Develop carbon capture technologies, electricity generation facilities, and industrial facilities. |

937 |

Industry, state/local, NGO |

TBD |

|

Industrial emissions demonstration projects |

Demonstration projects that test technologies that reduce industrial emissions. |

500 |

Industry, state/local, NGO |

2nd quarter 2022 |

|

Energy Storage Demonstrations |

Grants for three energy storage demonstration projects. |

355 |

Industry, state/local, NGO |

3rd quarter 2022 |

|

Long‑duration Demonstration Initiative and Joint Program |

Demonstration projects focused on development of long‑duration storage technologies. |

150 |

Private, state/local, NGO |

3rd quarter 2022 |

|

Energy Efficiency |

||||

|

Weatherization Assistance Program |

Formula based program for energy efficiency upgrades for low‑income households. |

$3,500 |

States, tribes |

Initial funds 1st quarter 2022 |

|

Energy Efficiency and Conservation Block Grants |

Assist states, local governments develop programs to improve energy efficiency. |

550 |

State/local, tribes |

Fall 2022 |

|

Electric Grid |

||||

|

Upgrading Electric Grid Reliability and Resiliency |

Demonstrate innovative approaches to transmission, storage, and distribution infrastructure. |

$5,000 |

States/local, tribes |

4th quarter 2022 |

|

Preventing Outages and Enhancing Grid Resilience |

Activities that supplement existing grid hardening efforts and reduce the risk of wildfire or reduce disruptive events. |

5,000 |

States, tribes, grid operators, private industry |

4th quarter 2022 |

|

Smart Grid Investment Matching Grant Program |

Investments that allow buildings to engage in demand flexibility and Smart Grid functions. |

3,000 |

Utilities |

By end of 2022 |

|

Energy Improvement in Rural or Remote Areas |

Increased environmental protection from impacts of energy use and improve reliability, safety, and availability of energy in rural areas. |

1,000 |

Private, state/local, NGO |

Fall 2022 |

|

IIJA = Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act; NGO = nongovernmental organization; and TBD = to be determined. |

||||

In many cases, detailed federal guidance about how the funding can be used and how it will be allocated is not yet available. As a result, it is unclear how the Governor’s clean energy package strategically targets funding in a way that best complements the federal IIJA funding. For example, are there opportunities to use state funding to leverage federal funds in a way that helps further the state’s goals? Some of the major federal programs—such as funding to prevent outages and enhance grid resilience—require a state match, but the Governor’s budget does not allocate funding for the state match. Another question is: Are there key gaps in federal funding that state funding can help fill? The Legislature might want to direct the administration to develop a strategy for using state funds in a way that best complements federal funding.

Expanding Scope of Certain Programs Could Improve Outcomes. The Governor’s proposal targets certain types of technologies and sectors, while excluding others. For example, although long‑duration storage and green hydrogen could be important technologies needed to meet the state’s SB 100 goals, other technologies that could potentially achieve similar goals would not receive funding under the proposal, such as geothermal energy. As another example, carbon capture projects that store carbon in products (such as cement) would be eligible for the industrial decarbonization program, but carbon capture projects with geologic storage would not. Finally, the proposal provides funding to an existing program for GHG reduction projects at food processing facilities, instead of making that funding available to a broader set of industrial facilities.

Limiting the types of eligible projects and sectors that qualify for funding creates a risk that the funds are not used to support the most promising emission‑reduction projects and technologies. A more technology‑ and sector‑neutral approach can be especially important when there is uncertainty about which technologies will prove to be most feasible and cost‑effective in the long run. The Legislature could consider modifying the programs and funding in ways that make a broader range of technologies and businesses eligible for the funding, while directing the administration to select projects based on their potential to help achieve long‑term GHG reductions in a cost‑effective manner. For example, the Legislature could create a program that focuses on a broad range of technologies that help the state achieve its SB 100 goals, which could include long‑duration storage and hydrogen power, as well as other technologies such as geothermal. Also, it could shift funding from the Food Production Incentive Program to the broader industrial decarbonization program, plus expand eligibility to include other technologies such as carbon capture with geologic storage. This could provide greater flexibility to fund the mix of industrial decarbonization projects that have the most GHG‑reduction potential.

Reporting Requirements Needed to Facilitate Legislative Oversight. The administration does not propose any formal reporting to the Legislature on program outcomes. We recommend the Legislature consider adopting requirements that the administration report annually on key program outcomes, such as estimated emission reductions, technological progress, key lessons learned, and key challenges. The Legislature could use this information when making future policy and budget decisions in this area, including whether to continue any of the proposed programs after the two‑year funding expires.

Some Proposed Spending Is Excluded From State Appropriation Limit (SAL). The California Constitution imposes a limit on the amount of revenue the state can appropriate each year. The state can exclude certain spending—such as on capital outlay projects—from the SAL calculation. The Department of Finance estimates that $644.5 million of the proposed spending is for activities that are excludable from the SAL. In constructing its final clean energy package, we recommend the Legislature be mindful of SAL considerations. For example, if the Legislature were to approve a lower amount of spending on the proposed activities that the administration excludes from SAL, it would generally need to repurpose the associated funding for other SAL‑related purposes, such as tax reductions or an alternative excluded expenditure.

Assessment of and Recommendations on Specific Programs

In this section, we provide comments that are specific to a few of the new programs and projects that are included in the Governor’s clean energy package.

Equitable Building Decarbonization

Focus on Decarbonization of Existing Buildings Has Merit. As discussed above, buildings are a substantial source of GHG emissions and a large‑scale effort to reduce building emissions is likely needed to achieve long‑term deep decarbonization goals. Pursuant to Chapter 373 of 2018 (AB 3232), CEC assessed the potential to reduce GHG emissions in residential and commercial buildings by at least 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030. This assessment identified expanding use of electric heat pumps and investing in electrification of existing buildings as key areas for building decarbonization efforts. Furthermore, in addition to GHG reductions, building electrification can have other important benefits, including reducing indoor air pollution from natural gas combustion and potentially reducing household energy bills.

Proposal Raises Key Questions About Statewide Building Decarbonization Strategy. The state has undertaken some analysis and planning related to building decarbonization efforts. In addition to the AB 3232 assessment discussed above, CPUC has an open rulemaking that aims to, among other things, establish a building decarbonization policy framework. However, CPUC has not yet adopted a long‑term policy strategy for statewide building decarbonization. Some key questions the Legislature might want to consider when evaluating this proposal:

- What Is the Role of Rebate and Direct Install Programs Relative to Other Building Decarbonization Policy Changes? For example, how much should the state focus on rebates and direct install programs compared to other building electrification options, such as changes to the structure of electricity rates that lower the volumetric (cost per kilowatt hour) rates?

- What Impact Will Electrification Efforts Have on Remaining Natural Gas Costs for Customers? The natural gas system has substantial fixed infrastructure costs. As a result, during a transition from natural gas appliances to electric appliances, remaining natural gas customers could be left paying much higher natural gas rates to cover a greater share of the fixed infrastructure costs. How will the state manage this transition in a way that does not result in substantially higher energy costs for households, especially low‑income households and renters who might be less likely to switch to electric appliances?

- Why Is CEC the Most Appropriate Agency to Administer the Direct Install Program? There are a wide variety of state entities in California that administer building energy efficiency programs. Notably, CSD operates several different programs that provide direct install energy efficiency services for low‑income households. The Legislature might want to ask why CEC—and not CSD—is the best state entity to administer this new program. If the main goal of the program is to ensure the funds are reaching low‑income households, CSD likely has the most experience administering these types of programs and working with third‑party contractors that can conduct this work. We are working with CSD to better understand: (1) how the specific components of the proposed program and CSD’s ongoing weatherization programs are similar and how they are different, (2) whether CSD’s local service providers could ramp up to provide the augmented level of service, and (3) whether there would be administrative costs at the department to oversee the additional funds.

Recommend Legislature Direct Administration to Provide Additional Detail on Equitable Building Decarbonization Programs. We recommend the Legislature direct the administration to provide additional detail on how these proposed programs fit in the state’s overall building decarbonization strategy and responses to the questions identified above. If, after these responses, it is still unclear why the proposed approach is the most cost‑effective or equitable, then the Legislature could scale back the amount of funding and/or focus funding in ways that help the state evaluate different options and develop a long‑term strategy. For example, funding could be used to pilot building decarbonization efforts in a limited (but diverse) number of communities. This might help the state better evaluate the benefits, costs, and challenges of a large‑scale building decarbonization effort, and help inform future legislative budget and policy decisions.

Oroville Pump Storage Project

Project Could Have Merit, but No Details on How Project Compares to Alternatives. This proposal has potential merit as a way to integrate renewable energy onto the grid by providing long‑duration energy storage. As discussed above, long‑duration energy storage will likely play an important role in meeting the state’s SB 100 goals. Additionally, according to the administration, this specific project is less costly than other pumped hydroelectric storage projects because the Oroville dam complex already has existing infrastructure for pump back operations. However, the administration has not provided a more detailed analysis that shows this project is more cost‑effective than other options, including alternative pumped hydro projects, other long‑duration storage technologies, transmission capacity upgrades and expansion, and/or other zero‑carbon technologies that could be used to balance the grid (such as geothermal or green hydrogen).

General Fund Would Pay for Project, but Future Financial Benefits Would Accrue to State Water Project. Once operational, the pump storage facility would use electricity to pump water uphill when electricity prices are relatively low and generate hydroelectricity when electricity prices are relatively high. As a result, the revenue from electricity sales is expected to exceed the electricity costs related to pumping the water and the higher maintenance and operations costs related to running the equipment. Although there is significant uncertainty about the net revenue associated with the project, the Department of Water Resources (DWR) projects that the project could generate a few million dollars in annual net revenue once it is operational. Under the current proposal, the project would be developed using state General Fund, but the net operating revenue would go to support the State Water Project and/or reduce costs for water users.

Recommend Legislature Direct Administration Provide Additional Justification. First, we recommend the Legislature direct the administration to provide additional information about the cost‑effectiveness of this project approach relative to other technologies and projects that might be able to provide similar types of benefits to the electricity grid. This could allow the Legislature to better evaluate whether the proposed project is the most cost‑effective approach to achieving the state’s SB 100 goals.

Second, if the Legislature provides General Fund for this project, we recommend it adopt budget trailer bill language requiring DWR to estimate the net annual revenue generated from the pump storage project once it is operational and transfer this amount of funding to the General Fund. In our view, if state taxpayers are providing the funding for this project, it would be reasonable for state taxpayers to receive the financial benefits from the project, rather than users of the State Water Project.

DWR Resources to Support Energy Reliability

$3 Million to Support Energy Reliability Efforts at DWR. The Governor’s package includes $3 million General Fund in 2022‑23 for DWR to support energy reliability activities. According to the administration, this funding would support actions that expand energy supply and storage in California in coordination with CEC, CPUC, and the California Independent System Operator.

Department Does Not Identify Specific Energy Reliability Efforts to Justify Request. It is unclear what specific activities this funding would support. The budget change proposal provides very little detail on what activities would be conducted. According to DWR, the funding would be used to support energy reliability efforts as needs arise, but DWR has not identified any specific activities yet.

Recommend Legislature Reject Proposal. We recommend the Legislature reject this request because DWR has not adequately described how the proposed $3 million would be used or justified the need for these resources.

Conclusion

Overall, the Governor’s proposed clean energy package could have merit as part of an overall strategy to achieve long‑term, deep decarbonization. However, as the Legislature considers this proposal, it will have key decisions to make about how it balances long‑term GHG reduction goals with other medium‑ and short‑term priorities, and whether there are modifications that could provide flexibility to ensure that the projects with the most merit are ultimately funded. To help inform its decisions on this package, the Legislature might want to direct the administration to provide more information on how this proposal complements the significant amount of federal funding available for energy‑related activities and how this proposal fits within the broader strategy of statewide GHG reduction efforts. Finally, additional reporting on future program outcomes could help the Legislature make more informed budget and policy decisions in the future.