LAO Contact

Other Reports in This Series

April 5, 2022

Climate Change Impacts Across California

K‑12 Education

- Summary

- Introduction

- Major Climate Change Impacts On K‑12 Education

- Significant Existing Efforts and Funding

- Key Issues for Legislative Consideration

- Conclusion

Summary

Climate change will have a number of serious impacts on California, including public health risks, damage to property and infrastructure, life‑threatening events, and impaired natural resources. This report focuses on how a changing climate is affecting early childhood and K‑12 education, and key issues the Legislature faces in responding to those impacts. This is one of a series of reports summarizing how climate change will impact different sectors across California.

More frequent wildfires and extreme heat waves will increase the likelihood that schools and child care providers will need to respond to climate‑driven emergencies and public health issues. More extreme weather events and conditions also negatively affect student learning, school facilities, and district budgets. Students are likely to experience more frequent climate‑related school closures, and schools may need to quickly shift between in‑person and remote learning. Districts will face higher and more volatile cost pressures in dealing with the wide‑ranging impacts of climate change, from higher utility bills on hotter days to massive recovery efforts after major emergencies. Additionally, school facilities will require modifications to withstand the harsh impacts of climate change. Child care providers and districts with smaller budgets and that serve higher numbers of lower‑income families could be particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, since they often have greater needs and fewer resources available to address such issues.

The state has supported several efforts to address climate change impacts on early childhood and K‑12 education, such as funding to support schools recovering from wildfires. However, several key questions remain for the Legislature to address. In particular, the Legislature will want to consider how the state can support schools in preparing for and responding to more frequent climate‑driven emergencies and public health issues. Steps could include directing state departments to ensure that schools are adequately included in statewide emergency planning, providing funding to districts for emergency management planning and facility risk assessments, and supporting plans to maintain continuity of services when impacts occur. In situations where schools and communities are severely impacted, the Legislature also will want to consider what the state’s role should be in supporting recovery efforts. In particular, a key question will be which types of recovery services should be handled by the state versus local education agencies. Moreover, preparing for and recovering from climate change impacts will come with varying fiscal impacts. Accordingly, the Legislature will want to consider how the state should assist schools in managing these costs—especially schools that face the greatest risk and/or have less capacity to prepare and respond to climate change impacts without state assistance.

Introduction

This report contains three primary sections: (1) the major ways climate hazards impact K‑12 education, (2) significant existing state‑level efforts underway to address climate change impacts in the education sector, and (3) key questions for the Legislature to consider in response to these impacts. Given the complexity of the issues, this report does not contain explicit recommendations or a specific path forward; rather, it is intended as a framing document to help the Legislature adopt a “climate lens” across the K‑12 education policy area. Many of the considerations we discuss also apply to early childhood education and child care.

Because some degree of climate change already is occurring and more changes are inevitable, this document focuses primarily on how the Legislature can think about responding to the resulting impacts. Of note, the state also is engaged in numerous efforts to limit the degree to which climate change occurs by enacting policies and programs to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases (such as by encouraging school buildings to be more energy efficient).

California Faces Five Major Climate Hazards. As discussed in depth in our companion report, Climate Change Impacts Across California: Crosscutting Issues, California faces five major hazards as the result of climate change. Specifically, increasing temperatures, a changing hydrology, and rising sea levels will lead to:

- Higher average temperatures and periods of extreme heat.

- More frequent and intense droughts.

- Increased risk of floods.

- More severe wildfires.

- Coastal flooding and erosion.

Below, we discuss specific impacts these hazards will have on K‑12 education.

Major Climate Change Impacts On K‑12 Education

In this section, we discuss current and future impacts that climate change will have on early childhood and K‑12 education. Overall, we find that climate change will increase the likelihood that schools and child care providers will need to respond to climate‑driven emergencies and public health issues. This likely will require schools and providers to take steps to avoid disruptions in providing educational services when impacts occur and to modify their facilities.

Climate Change Impacts Increase Likelihood That Schools Will Need to Respond to Emergencies and Public Health Issues. Schools and child care providers are already beginning to experience the impacts of climate change, most notably from wildfires. For instance, the California Department of Education (CDE) reports that 104 school districts were subject to wildfire evacuation orders in 2020. In addition to emergencies, climate change impacts may also lead to public health issues that require modifications to educational delivery models. For example, extreme heatwaves or poor air quality from wildfires may make it temporarily unsafe for students and staff to participate in normal outdoor activities. Accordingly, schools and child care providers will need to establish and continually update emergency preparedness and response plans that adequately reflect the increased likelihood and intensity of these events.

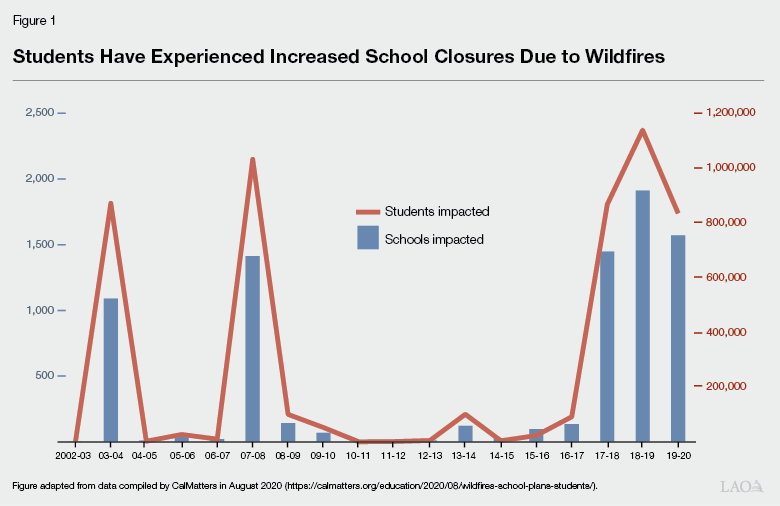

Schools Will Need to Take Steps to Avoid Disrupting Education and Services. As the climate changes, K‑12 schools and child care providers will experience more frequent closures due to the impacts of wildfires, not only from the encroaching fires but also from planned power outages and smoke‑related impairments to air quality. For instance, as shown in Figure 1, from 2008‑09 to 2016‑17, an average of about 70 schools experienced wildfire‑related emergency closures each year. In contrast, the state averaged more than 1,600 schools closed due to wildfires annually from 2017‑18 through 2019‑20. These closures affected an average of about 950,000 students in 2017‑18 through 2019‑20.

In some areas of the state, educators and students may also increasingly be impacted by flooding that disrupts their ability to get to school or impairs the functionality of school facilities on a short‑ or long‑term basis. More frequent closures will cause disruptions to education, special education services, school meals, child care, and other services. As a result, impacted students will face a higher risk of experiencing food insecurity, learning loss, and, consequently, poorer academic outcomes. Additionally, following traumatic climate‑related closures, students may experience mental health impacts, which also can affect their ability to learn. School and child care closures also impact parents’ ability to work, depending upon whether they are able to make alternative care arrangements. Lower‑income families are likely disproportionately impacted by disruptions to education and child care because they often have fewer available resources to help mitigate the disruptions—including challenges such as less access to computers, unreliable internet connections, inadequate space at home for remote learning, less capacity for adults to monitor student engagement, less exposure to English for English learners, or inability to arrange and pay for child care alternatives. Additionally, districts and counties along the state’s southern border have recently seen influxes of unaccompanied minors from Central America due in part to climate change impacts like the economic impacts of hurricanes, spurring an urgent need to provide educational services to significant numbers of children. Schools and child care providers will need to plan for how they can maintain continuity of education and services—particularly for more vulnerable and impacted students—as climate change disruptions become more frequent.

Climate Change Will Require Modifications to Many Existing and Future School Facilities. Historically, infrastructure has been designed under the expectation that future conditions would be relatively stable and reflect historical trends. However, as the climate changes, school and child care facilities will need to be able to withstand more extreme events and conditions than those for which they were designed. For instance, to meet the demands of warmer average temperatures and more frequent heatwaves, school facilities in historically temperate regions may need to consider remodeling playgrounds with more heat‑resistant materials and shade structures or adding air conditioning systems—which some research has found to mitigate the negative impacts of heat on student learning and academic performance. Additional modifications might include “hardening” facilities to reduce their risk of catching fire in forested areas, adding air filtration systems to lessen smoke exposure, or elevating structures along the coast to accommodate occasional flooding. Construction of new school facilities will also need to incorporate the impacts of climate change. For example, design standards and siting requirements for new schools will need to consider the increased potential of future flooding from rising sea levels rather than relying solely on historic trends to assess a location’s flood risk.

Responding to Impacts of Climate Change Will Have Fiscal Impacts on Schools. Schools and child care providers will incur additional costs in preparing for and responding to the impacts of climate change. Some of these costs will be somewhat predictable and can be built into long‑term planning. For example, expected costs might include higher utility bills from increased reliance on air conditioning during extremely hot days, making necessary facility modifications, or purchasing additional computers and technology upgrades to allow for temporary shifts to remote learning when wildfires make air quality unsafe to attend school. In contrast, the costs associated with responding to climate‑driven emergency events are more difficult to predict and plan for, and could be significant. Such costs might include relocating schools to temporary locations, repairing or rebuilding damaged schools, purchasing and deploying protective equipment such as sandbags to prevent flooding, or providing staff and students with face masks to protect from smoke. For example, the Camp Fire of November 2018 caused significant damage to schools in the Paradise Unified School District. Despite one‑time federal recovery funds and sustained levels of state school funding, a 2020 evaluation found the district will continue to face long‑term fiscal impacts from fire‑related cost pressures such as higher attorneys’ fees, transportation costs, and insurance premiums. Districts also may face more volatility in enrollment as some families choose to permanently relocate to other places after emergency events—likely driving enrollment declines in certain communities and growth in others, as well as corresponding changes to state school funding.

Significant Existing Efforts and Funding

The state has supported several efforts to address climate change impacts on K‑12 education, such as funding to support schools recovering from wildfires, as well as department initiatives to streamline communication between the state and schools during emergencies. Below, we highlight some of the most significant climate adaptation efforts the state has undertaken related to schools.

State Law Provides Continued Funding for Schools When Impacted by Disasters. Under current law, schools generate state funding based on student attendance. When a disaster—such as a fire or flood—results in school closures and lower student attendance, schools may request continued state funding comparable to what they would have received had they not closed. For instance, schools impacted by the Camp Fire in 2018 and Tubbs Fire in 2017 requested and received such continued state funding. Additionally, the 2021‑22 budget provided $4.2 million in one‑time state funding to the Paradise Unified School District to help cover increased costs following the Camp Fire.

Schools Impacted by Future Disasters Must Plan for Independent Study. The 2021‑22 budget package established additional requirements for schools to receive continued state funding following a disaster‑related closure. Specifically, as of September 1, 2021, schools must develop a plan to offer independent study to students when school is closed and then reopen for in‑person instruction once permitted under their local health guidance.

Additional Emergency Planning Requirements for Special Education. Each student that qualifies for special education receives an Individualized Education Program (IEP) specifying the services and supports their district will provide. The 2020‑21 budget package established a new requirement for IEPs to also describe how services and supports will be provided during an emergency when in‑person school is closed for more than ten school days.

CDE Added Staff Dedicated to School Emergency Preparedness, Response, and Recovery. The 2020‑21 budget provided CDE with two positions to support schools across the state in planning for, preparing for, and responding to disasters, including climate‑driven events. The 2021‑22 budget subsequently provided $264,000 in ongoing funding for these positions.

CDE Has Recently Developed Additional Emergency Support Services for Schools. CDE has undertaken several recent activities to help schools respond to climate change impacts. First, for schools affected by wildfires, CDE helped find facilities that could be used as temporary classrooms and apply for state and federal funding. Second, in 2019, CDE partnered with the California Air Resources Board and other organizations to issue statewide guidance for schools on recommended activities under poor air quality conditions. Third, to streamline future communication between CDE and schools during emergencies, the department recently established an emergency response system for schools. The system allows CDE to directly send out and gather information from schools affected by disasters.

Key Issues for Legislative Consideration

Because schools are primarily managed at the local level, many of the decisions about how to adapt to climate change impacts will be made by governing boards and district and site administrators. However, given the state’s constitutional responsibility to provide public education, the state has an important role to play in ensuring that schools are prepared to keep students (1) safe and (2) learning despite the climate change impacts they will experience and resulting changes to current operations that they may need to make. Below, we discuss key issues for the Legislature to consider given these important state responsibilities in the context of a changing climate, and also summarize these issues in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Climate Change Impacts on K‑12 Education:

Key Issues for Legislative Consideration

|

|

|

|

|

|

How Can the State Support Schools in Preparing for and Responding to More Frequent Climate‑Driven Emergencies? With climate‑driven emergencies expected to become more frequent and intense, the Legislature will want to ensure that schools are prepared to quickly and capably respond to such events. Preparedness and response activities will need to be conducted at both the state and local levels, with many efforts requiring collaboration across different agencies. At the state level, the Legislature will want to ensure that schools are adequately included in statewide emergency preparedness and response planning efforts, such as by requiring state agencies to consult with CDE prior to developing state‑level emergency plans or requiring—and verifying—that local city and county disaster mitigation plans incorporate potential impacts on schools. The Legislature also will need to consider how it can support local efforts. This could include encouraging the development of up‑front mutual aid agreements between schools for providing post‑disaster services. The Legislature also could consider funding emergency management planning grants for districts and county offices of education (COEs)—specifically those that face the greatest risk and/or might have less capacity to prepare and respond to climate threats without state assistance. Additionally, the Legislature will want to think about whether the state currently has the information it will need to support statewide efforts in preparing for and responding to climate‑driven emergencies. For instance, would the state benefit from having a statewide inventory of school facilities to help identify which sites might be at risk during fire or flood events?

What Role Should the State Play in Supporting Schools Recovering From Climate‑Driven Emergencies? While being adequately prepared to respond to climate‑driven emergencies can mitigate losses, there still will be situations in which schools and communities will be impacted and recovery efforts will be needed. Such efforts may range from fixing or relocating damaged school facilities to finding temporary facilities to continue instruction and providing emergency meal and mental health services. The need for recovery efforts and services likely will become more regular as climate change impacts become more frequent and intense. Accordingly, the Legislature will want to consider what the state’s role should be in supporting schools that are recovering from climate‑driven emergencies. For instance, should the state be responsible for arranging and bearing the costs of certain recovery services and not others? Should the state’s approach vary depending on the characteristics of the communities that are impacted? For example, should the state provide additional support for school districts that have fewer resources to cope and recover from climate change impacts compared to those that have larger operating budgets? What lessons has the state learned from recent disasters that can inform future recovery efforts?

What Role Should the State Play in Assisting Schools in Navigating Climate‑Driven Public Health Impacts? Schools will have varying degrees of technical expertise—or, in some cases, none—regarding how they should respond to climate‑driven public health impacts such as prolonged periods of extreme heat and wildfire smoke. In response, the Legislature may want to consider what information or guidance the state should provide to help schools’ administrative decision‑making. For instance, the state could set clear guidelines on what particulate matter air quality levels should prompt school closures or what temperatures should shift activities indoors.

How Can the State Help Support Continuity of Educational Services? As disruptions to education and child care services occur more frequently, the state will want to consider ways to support schools and child care centers to ensure continued access to services. For instance, in recent years, districts in other states have developed capacity to swiftly switch to remote learning when inclement weather has led to the cancellation of in‑person school. The Legislature may want to explore statutory changes that would require districts to make up instructional days lost due to wildfire smoke, extreme heat, or flood events, either through distance learning or other means. The Legislature could also require that schools and child care providers develop plans for how they will maintain general education and special education services, learning recovery, emergency meal service, mental health services, and child care in cases of extreme weather and climate‑driven events. The Legislature also could consider what role, if any, the state should play in supporting districts and COEs in planning for or providing education to increased numbers of children who may migrate to the state as a result of climate change impacts they experience in other states or countries. Since connectivity issues and food insecurity are more likely to affect lower‑income students, the Legislature will want to consider providing additional resources after disruptive events specifically to ensure schools prioritize meeting the needs of these students. Additionally, the Legislature could consider whether the state should maintain a reserve of portable classrooms or signal that existing state emergency funds could be used for technology devices that could be readily deployed after a climate‑driven emergency to support continuity of services.

How Can the State Ensure That School Facilities Are Prepared to Safely Withstand the Impacts of Climate Change? Schools will need to conduct assessments, plan, and implement strategies to ensure that their facilities are more climate resilient. Policy levers the Legislature could consider include providing technical assistance and financial incentives for facility risk assessments and adaptation planning, updating the state’s School Facilities Program and school facility regulations to incorporate climate change impacts, and directing state agencies to collaborate and develop statewide guidance for ways school facilities could be modified to be more resilient to climate change. The Legislature also could consider reserving a specified amount in future school facility bonds for projects explicitly intended to prepare facilities for the anticipated impacts of climate change.

How Should the State Help Schools Manage the Fiscal Impacts Associated With Climate Change? The Legislature will want to consider the role the state should play in addressing the many fiscal impacts schools will experience in preparing for and responding to the impacts of climate change. Specifically, which types of costs and financial risks should be borne at the state level, as compared to relying primarily on local resources? For instance, the Legislature could decide that because districts, charter schools, and child care centers should be able to plan and budget for the more predictable fiscal impacts of changing climate conditions, they should cover costs such as increasing utility bills and planned facility modifications within their operational budgets and existing state programs (such as the School Facilities Program). In contrast, schools may find it more challenging to fully pay for more significant, unpredictable costs such as major damages to facilities. Are there ways the state can encourage districts and schools to establish regional risk pools to help cover costs associated with response and recovery following a climate‑driven event? Should the Legislature consider statutory changes to help districts affected by climate‑driven fluctuations in student enrollment and, consequently, state funding? The Legislature also could explore whether the significant potential costs associated with experiencing climate disasters should factor into setting district reserve caps, guidance for minimum reserve levels, or the state’s fiscal oversight process. For example, should schools located in regions that have been identified as high fire risk areas be required to carry larger reserves? What special provisions—if any—should the Legislature consider to help prepare smaller districts and child care centers to fiscally rebound from climate‑driven events, given their smaller operating budgets and economies of scale?

Conclusion

Climate change will have increasingly severe impacts on early childhood and K‑12 education—particularly from more frequent wildfires and extreme heat waves. These threats will layer on top of schools’ existing challenges, such as addressing achievement gaps and meeting the needs of English learners. Confronting the effects of climate change will be challenging. However, the consequences of inaction could be even more severe, and will worsen over time as climate change impacts become more frequent and intense. In many cases, schools will struggle to prepare for these impacts on their own and will need state guidance and support.